Secret Wars:

Writing an Article about Imam Ali and Super-Heroism

(In keeping with academic convention, a semicolon must be inserted in the title. It made its first appearance before either the author or the editorial team was born, back in issue #666…)

Or…

Witness to the Academic Article Sausage-Making: A Multi-Issue Crossover Event!

Hussein Rashid

The Amazing Introduction #786

Several years ago, I met A. David Lewis and we connected over our shared interest in religion and comics, although we were coming at it from different disciplinary perspectives.

He eventually suggested I meet with a colleague of his, Martin Lund,1 who was also interested in religion and comics, and was then visiting New York, home of the superhero. Martin and I met for a tea and chatted for a bit about our interest in the topic that brought us together, and some of our favorite books. Towards the end of our conversation, Martin asked if I would submit a proposal for a chapter in a volume he and David were editing on Muslim superheroes.2

I immediately said “yes.” That simple, one-word statement began a series of adventures and arguments that have transformed this humble author from an academic introvert into Misanthropic Recluse Man!?!™

This blog post is an attempt to record and ruminate on the process of transformation. It will hopefully stand as a guide for those who come after me, to understand how to write that article for an edited volume; appreciate the perils and joys of multidisciplinarity; embrace the power of good editors; engage the importance of language; and know the need, always the need, for good tea.3

What If #1

My immediate thought for the article was to look at the work the good folks at Sufi Comics are doing.4 They take the stories of Prophet Muhammad and his family, considered by many Muslims as the ideal of what it means to be Muslim, and illustrate teachings from their lives. My goal was to talk about cultural flows and hybridity theory.

Muhammad and his family are the original heroes for Muslims, and their virtuous behavior is being represented through the American art form of the comic, by artists from India. This approach seemed like a way to look at the transnational nature of Muslim identities, while still taking national particularities into account.

Within this framework, I could bring in discussion of the miniature painting tradition, to show how illustrated heroes’ tales were not foreign to Muslim traditions. My thinking was shaped by the initial call for proposals and thinking about comics and Muslim superheroes. But, as I delved further into the topic, I realized that I was saying the wrong things. I was trying to make one tradition fit into another tradition. Instead, what I should be doing was unearthing an emic understanding of the hero from Muslim cultures.

Peerless Hero #110

The obvious place to begin defining a Muslim hero is with the Prophet Muhammad. He is revered by all Muslims, and is explicitly called an exemplar in the Qur’an (33:21). However, like all prophetic figures, describing his heroic qualities is made more complex by his relationship to God. Different schools of thought understand Muhammad’s relationship to the Divine in different ways, so it becomes difficult to generalize broader principles of heroism from Muhammad’s actions.

The family of Muhammad seems to be next logical place to find models of heroism. Like Muhammad, they are universally respected, and the family closest to him, Ali, Fatimah, Hasan, and Husayn, all knew Muhammad as well. Muhammad’s uncle Hamza is also a well-known figure, and a genre of Hamza’s epic adventures, captured in Hamzanamahs, emerges in Islamic literatures. Hamza predeceases Muhammad and is not vouchsafed in the Qur’an as part of Muhammad’s near family, as the other four family members are. As a result, his stories do not carry the same weight as those about Fatimah’s family.

Hasan has very few stories about him that extend beyond the biographical literature. The corpus of devotional work to Husayn is much richer, but tied to his martyrdom at Karbala, and so often takes on a more distinctly Shi’i flavor, rather than a universal one.

We are left with Fatimah and Ali. There are a large number of stories about both figures, both individually and alone, although stories of Ali by himself are significantly more numerous. Since the goal of the article was to look at the work of Sufi Comics, their selection of stories related to Ali made him the logical choice for a case study of Muslim notions of the hero.

Definition Man #1

Once I had the heroic figure established, I need to establish a way to talk about heroism in a Muslim context. Like Dr. Strange’s Book of Vishanti, I thought I had a powerful tome in John Renard’s Islam and the Heroic Image. While the book proved to be an invaluable resource, it did not give me a clear enough definition of the Muslim hero around which to frame my argument.

I went to David and Martin, and admitted my shortcomings. I am an Islamicist, and broadly speaking, know Religious Studies. I also know the X-Men universe. However, I am not as well versed in the academic literature of heroes. I explained my inability to articulate a concise definition of the hero, and asked for their suggestions. They suggested that I create my own definition based on what I was reading.

And I started to explore a definition, but that was still loose and ill-defined. I submitted to them something I thought of as mashed potatoes: bland and ill-formed, but still edible. After they gave it some seasoning, and maybe some more texture, we might make a side dish together. They agreed it was the consistency of mashed potatoes, but somewhat darker, inedible, and perhaps like something Lockjaw would produce when Black Bolt took him for a walk.

Obligatory comic geek digression: Lockjaw, the second most famous super hero dog in comics history. A member of the Inhuman royal family, Lockjaw teleports and is possessed of superhuman (or supercanine) strength. He has taken on the Thing and the Silver Surfer, and more recently has hung out with Kamala Khan, Ms. Marvel. Art credits: (top) Jack Kirby, Fantastic Four Vol. 1 #46 (1966) and Silver Surfer Vol. 1, #18 (1970); (bottom) Adrian Alphona, Ms. Marvel Vol. 3, #8 (2014) (© Marvel).

We had some discussion and agreed that trying to formulate a new definition of a hero ex nihilo, particularly when our intended audience would come from a variety of backgrounds, was not the best idea we had. They sent me back to do some research on the idea of the superhero and how it may be defined. What I found more fun than the rough attempt to schematize the superhero were the critiques. The clearest definitions of a superhero were descriptive, based on the traits present in the heroes the authors chose. People who read about other heroes, including greater gender and racial diversity, found different characteristics of the hero. Pieces by comics creators also suggested a broader vision of what heroes meant to them.

As I state in my article, a comic superhero is someone “who has a ‘universal, prosocial mission’; has superpowers, including technological or mystical abilities; and has an identity tied to costume and codename.” However, the Muslim superhero is more than this simple definition. The only point of commonality is the “prosocial mission.” I still have so much more work ahead in defining a Muslim superhero.

Captain Academic Jargonese #0

I now find myself in a position where the idea of a superhero, even with all sorts of caveats, does not apply to Ali. Nor is Ali simply a hero. At his core, Ali is a religious hero, and has a special connection to the Divine as the source of his strength. He, and his heroic acts, functions very differently than a superhero like Captain America. Therefore, Ali is neither a hero nor a superhero, but a hero that is uncanny. Since that phrase, “a hero that is uncanny,” would be awkward, even in an academic text, I opted to use “super-hero.”5 The key element of this super-hero is that he has a special relationship with God and has a God-given ability as a result of this relationship.

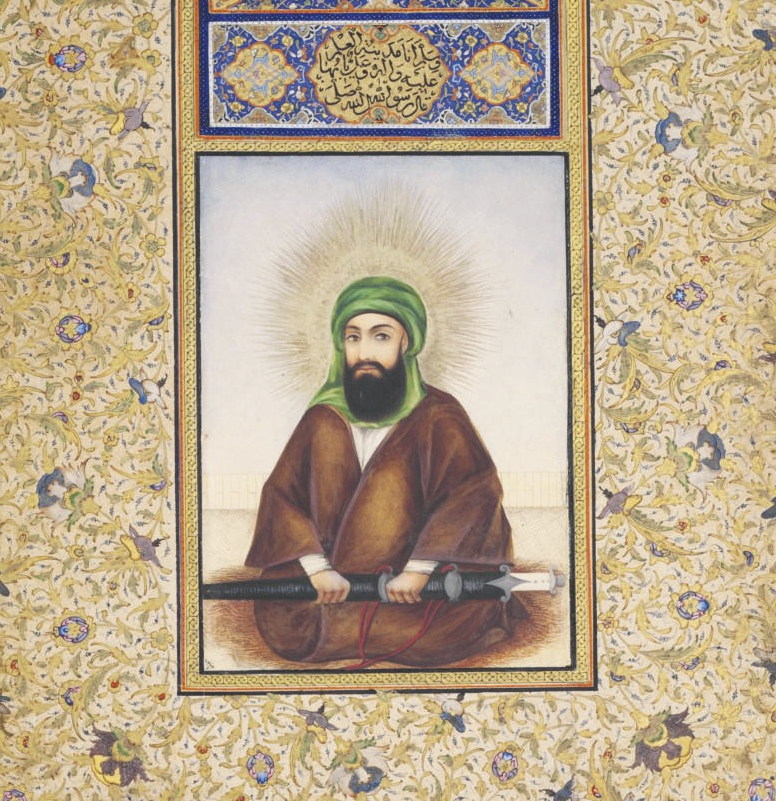

One story I allude to in the article itself is Ali at Khaybar. According to some traditions, Muhammad is laying siege to a fort, but cannot gain access. At this point, the Archangel Gabriel comes and tells Muhammad to recite the invocation, naad-e Ali, which would summon Ali, who is not at the battle.

Detail, manuscript illumination, ʿAli Fighting to Take the Fortress of Qamūṣ, from Athār al-Muẓaffar (The Exploits of the Victorious), Iran, 16th c. (Chester Beatty Library Per 235, f. 132a; courtesy Chester Beatty Library).

The English translation of the text is:

Call Ali call Ali call Ali

Call Ali, the manifestation of marvels

He will be your helper in difficulty.

Every anxiety and sorrow will end

Through your friendship. O Ali, O Ali, O Ali

Once Muhammad calls Ali, Ali appears and tears the gates of the fort off their hinges. Ali, of course, is accompanied by his horse Duldul and carries his signature weapon, Dhulfiqar.

This story is richly illustrated and an important part of performative traditions. The two examples I give here, one an illustration, and the other a modern rendition of a qawwali from the UK, demonstrate the importance of this tale.

Almost all of Ali’s heroic qualities are present in this story, and allowed me to craft a definition of a hero in Islam. Ultimately, I wrote:

Using Ali as a case study, we can create a working definition of an Islamicate hero. The hero has a special relationship with God, and as a result has a God-given ability…. Many heroes have special weapons. The hero is human and can die. The special relationship with the Divine is not a mark of invincibility or immortality. The hero is not supernatural but the “extreme realization” of human abilities, which means the hero has physical human weaknesses. Most importantly, the hero acts from a moral conviction, which is consistent with Divine guidance and revelation. The hero can never be a vigilante who operates outside of the law, although she does fight against tyrannical and oppressive powers. Nor can the justice that the hero fights for simply be about personal strength and ability; it is not about the hero imposing her will.6

This working definition made us all happier. We could not get to a truly independent understanding of what a hero is in Islam, but this definition seemed to illustrate the point of the cultural flows embedded in my article. It also demonstrates the ways in which cultural understandings of heroism are not always neatly defined and schematized; the hero is an organic representation of cultural norms and aspirations. The religious overlay may add some unity, but does not promise simplicity or consistency.

Dark Knight of the Soul #∞7

Our valiant struggle to define what makes a Muslim hero (or super-hero) was worth it. The clarity it offered to understanding the role of Ali was immense. I could take the wide collection of stories about Ali and parallel it with his teachings. The connection between what Ali represents in his quest for justice and his actions in various tales became more apparent.

However, where the definition was a good melding of different areas of expertise, some of our other discussions were more fraught because of the fact that we made assumptions about what the others knew. For example, at one point I mentioned a Pamiri folktale, and the comment came back asking what “Pamiri” meant. I wrote back a long paragraph about the Central Asian region of the Pamirs, and in particular Tajikistan, where the story was from. It was clearly done with an eye-roll and an “ugh, how can you not know this.” The edit I got back was along the lines of “a folktale from the Pamirs, a region of Tajikistan.” They wanted clarity and I thought I had it. The exchange was a good exercise in remembering your audience.

The other thing we did was get into epic nerd fights. A note on one of Batman’s nemeses survived the editorial process and is worth reading in context. Another was on the origin of the word “hero.” Martin made a comment on the original Greek meaning of the term, and I had to trump him with the Indo-European root. These diversions were fun, and deepened my thinking about the discourse in which the article is embedded.

League of Alternate Heroes #5 – a mini-issue

Focusing on Ali makes the most sense for this article. However, I think there is value in seeing how the basic definition I offer might hold up for other universal Muslim heroes. The question of gender as it applies to Fatimah and heroism is incredibly important. Hasan and Husayn are clearly linked to Shi’i traditions, but they are also important in the devotional and mythic lives of other Muslim communities.

How Muhammad’s prophetic status affects notions of the hero should complicate my definition, or require a totally separate definition for a hero. The ways in which the awliya (Friends of God, saintly figures who are loci of Divine favor) hew to this definition (and I believe they do) should also be examined.

There is a plethora of vehicles for exploring emic notions of Muslim heroism. These heroes are alive and as much a part of the cultural lives of modern Muslims as Iron Man and Ms. Marvel are.

Nothing Good Can Come of This – Epilogue

Our hero comes to the end of his epic quest. We are now in the omega issue, the akhir, where we expect a resolution. Yet, like any good story, the omega is also the alpha, the akhir is the ibtida. How the article is made is not the same as the article, and what comes after the article is not the same as the article. Everything is connected.

Here, dear reader, I want to point out that one should never see how legislation, sausage, or academic articles are made. And at least two of these three things are not always good or useful in their completed forms. Yet, it is fun and exhilarating to make these things and see them come to life.8

After this blog post, the next item you will see from me on this article is the article itself, in the edited volume Muslim Superheroes. It is worth a read and may inspire you to take up some of this work yourself. Pick up your magic pen and begin writing, after you cast the spell to order the book.

And at all times, remember to have a good cup of tea handy.

HUSSEIN RASHID grew up not sure why being a nerf herder was a bad thing. He advocates for contingent faculty and currently sees the fact that more than 70% of the professoriate work in contingent positions as a parallel to labor on the first Death Star. The labor is forced, but standards are still high. However, administrative greed and lack of concern for workers cause the whole system to catastrophically crash. His research interests focus on representations of Muslims in American popular culture, and he dabbles in Shi’ah Studies.

[1] Martin appears in his own ongoing series, Captain Curmudgeonly Hermit-Man.™ Most recently, he has been at work turning Superman into an atheist, with no religious roots. See his new book Re-Constructing the Man of Steel: Superman 1938-1941, Jewish American History, and the Invention of the Jewish-Comics Connection (Springer, 2016).

[2] A. David Lewis and Martin Lund (eds.), Muslim Superheroes: Comics, Islam, and Representation (Mizan Series 1; Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017). David never told me about this anthology, and I maintain it is because he hates me. He denies this and says it is more antipathy than hatred.

[3] While Douglas Adams may have you thinking he knows tea, no one knows tea like Misanthropic Recluse Man!?!™

[4] I say they are good folks, because they have always promptly answered every e-mail I send them, and they released images from their site for us to use in the chapter. You can get their first e-book for free from their website, which is a bonus (www.suficomics.com).

[5] The hyphen does a lot of work for me in this article. In addition to making the reader read carefully for “superhero” and “super-hero,” it also connects me in some small way back to notions of hybridity. It is a comfort blanket.

[6] Of course this passage is properly footnoted, but that’s only available in the anthology. Go buy it. There’s some good stuff in the notes. The rest of the volume is excellent as well.

[7] There is nothing redeeming about DC Comics, except for G. Willow Wilson’s run on Superman. Do not read this section title as endorsing DC in any way.

[Ed. note: G. Willow Wilson wrote Superman Vol. 1 #704 and 706. Her Vixen mini-series for DC was also pretty cool. Misanthropic Recluse Man!?!™ also forgets that Wilson’s acclaimed graphic novel Cairo and ongoing series Air were published by Vertigo, an imprint of DC. – Pedantic Pregill.]

[8] If you are wondering when I have been involved in legislation, you are clearly not familiar with the Twitter hashtag #CreepingSharia.