Of Censorship and Creativity

Iranian Cinema under the Islamic Republic

Rahad Abir

In director Jafar Panahi’s 2003 film, Crimson Gold, Ali (Kamyar Sheissi) asks Hussein (Hussein Emadeddin), “Tell me, what was it like in your day? Women really went out naked, without veils?” Ali, who grew up under the Islamic regime, is referring to the time in Iran before the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Hussein was seventeen or eighteen when the Shah fell, and he later fought in the Iraq-Iran War. At the time of Ali’s question, Hussein is working as a pizza delivery man, he has PTSD and suffers physically and emotionally. At the movie’s end, he takes his own life during an attempted armed robbery of a jewelry store.

Jafar Panahi, who calls himself a “socially conscious” filmmaker, uses Hussein in Crimson Gold to show the fiercely bifurcated life and culture of Tehran. Yet, audiences in the country never heard Hussein’s answer to Ali’s question. The film was rejected by censors and was never allowed to be screened in public in the Islamic Republic of Iran.

“Censorship,” writes actress and author Shahla Mirbakhtyar in Iranian Cinema and the Islamic Revolution, “did not allow the development of an Iranian cinema that could reflect all aspects of society and be a mirror of the variety of life and experience within the nation.” By and large, censorship pushed Iranian movie makers to employ only certain characters and tell stories in particular ways. “According to censors,” Mirbakhtyar explains, “films could not show such figures as alcoholics, gamblers or adulterers. A woman who was a teacher or a lecturer could not be portrayed in anything other than in a morally acceptable fashion.”

In pre-revolutionary Iran, restrictions were largely linked with censoring dialogue criticizing the mounting repression of the Shah’s rule, while in the post-revolutionary era, the restrictions are religious, political and cultural, and are widely considered to be part of a comprehensive plan to purify and Islamize Iranian society. The first speech of Ayatollah Khomeini upon his return from exile in February 1979 confirmed his view on cinema: “We are not opposed to cinema, to radio or to television . . . The cinema is a modern invention that ought to be used for the sake of educating the people, but as you know, it was used to corrupt our youth. It is the misuse of cinema that we are opposed to, a misuse caused by the treacherous policies of our rulers.”

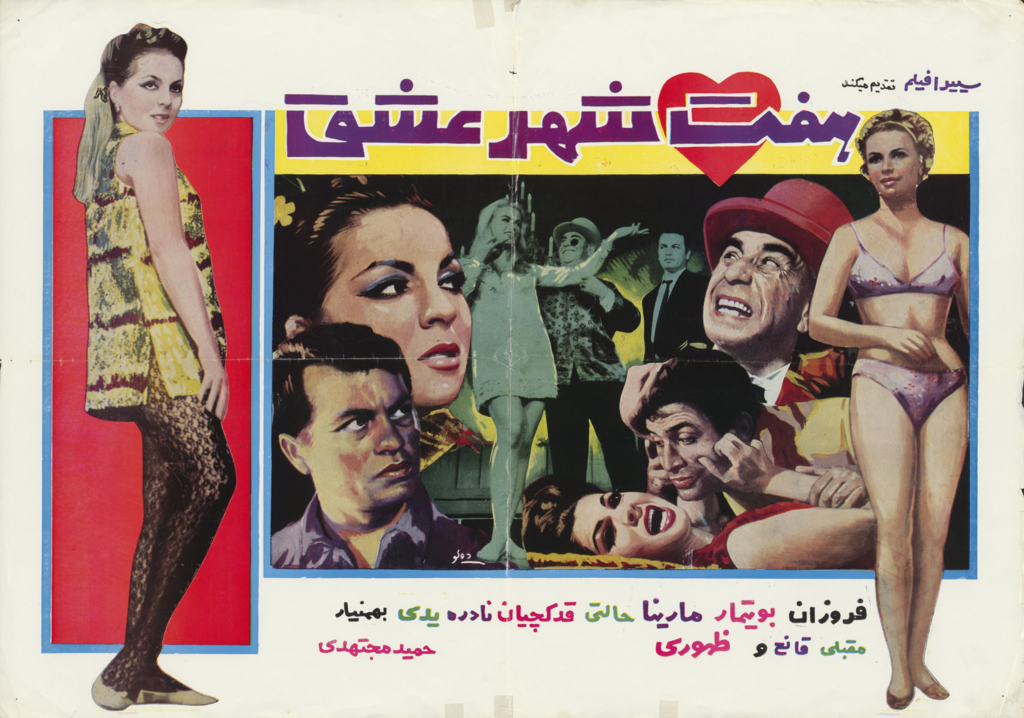

During the Islamic revolution, 180 out of 436 Iranian cinemas were burned to the ground. On 19 August 1978, The Washington Post reported that at least 377 people were killed in an inferno in the Rex Cinema in the city of Abadan. An audience of about 700 were watching the film Reindeer when the arsonists set the movie house ablaze. After the event, until Ayatollah Khomeini’s rise to power in early 1979, all the cinemas across the country remained closed or were turned into storage spaces and religious auditoriums. The enormous billboards depicting scantily clad women to advertise films were gone. The era of Iranian films featuring female characters wearing revealing dresses, singing and drinking liquor and performing sultry dances was over.

In the first few years after the revolution, Iranian cinema was in limbo. The Islamic regime saw the medium as a useful propaganda machine for indoctrinating the masses. It began to fund and promote films that supported religious and revolutionary ideals and interests. Films that didn’t measure up were banned or illogically cut, reedited, and had offending features painted over. Noted directors were discouraged from working. Celebrated actors were barred from the screen. The policymakers were determined to cleanse the cinema and culture, politically and morally, from the heavy influences of Western cultures and ideologies. The Ayatollah’s film edicts were not universally accepted. Unwilling to stop making films, some of the country’s foremost filmmakers including Abbas Kiarostami, Bahram Beizai, Daryush Mehrjui, and many others led by Mohsen Makhmalbaf and Rakhshan Banietemad, broke their silence. They set out on a tumultuous journey to return to work in the newly formed Islamic Republic.

One of the issues they were forced to overcome was the depiction of women in their films. After 1979, any representation of women in Iranian films became problematic. Female characters had to be extremely modest, and female bodies, apart from the face, hands and feet, had to be fully covered. Filmmakers were to make sure female actresses used little or no make-up and direct eye contact between men and women was discouraged. Mohsen Makhmalbaf advised filmmakers “not to use women at all or to give them peripheral roles, for fear of moral danger.”

According to eminent film scholar, Hamid Naficy, the state became fanatic about creating an increasingly narrow Iranian identity and policymakers felt they needed to “institutionalize a new film industry whose values would be commensurate with the newly formulated Islamicate values.” To bring film production and exhibition under centralized control, the government adopted “a draconian system of state regulation and patronage to encourage politically correct movies.” Censors began to use black ink and magic markers to paint over the bare legs and exposed body parts of women in films shot in the Pahlavi era. And when the magic marker wasn’t much help, they simply cut the scenes.

University Archives, Northwestern University Libraries. “Bandari.”, Hamid Naficy Iranian Movie Posters Collection. Accessed Wed Sep 30 2020.

Naficy interviewed the New-Wave director Bahman Farmanara about the extremes of post-Revolution film censorship. Farmanara was held in the country after he returned to Iran to see his ailing mother in 1983. “They interrogated me twenty-five different times,” said Farmanara, “sometimes with a revolver placed in front of me on the desk. They questioned my personal relationships and accused me of making anti-Islamic films.”

It wasn’t just filmmakers who were under threat by censors. Many popular actors of the pre-revolutionary period found themselves sidelined by the new regime and suffered “financially and psychologically.” Fardin, a renowned actor and director described his situation this way: “I am an actor, but I am not acting. I am like a fish out of a fishbowl.” Irene Zazians, another Iranian-Armenian star banned from working after the Revolution, said she was “unemployed and unemployable.” She eventually opened a beauty salon to make ends meet.

Once firmly in power, the Islamic Republic set off to purify and Islamize cinema. The Farabi Cinema Foundation was founded in 1983 to promote a Farsi film culture based on Islamic values. Later, the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance (MCIG) was set up to bring film production under strict control and censorship. In post-revolutionary Iran, policymakers wanted to establish a pervasive anti-Western, anti-American sentiment, and cinema was deemed to be the best medium for that. In February 1983, a filmmaking code was finally approved by the cabinet of Mir-Hossein Mousavi. The Supervision and Exhibition unit of the MClG was given responsibility for the “censorship of movies and videos” and overseeing the activities of the film industry.

Many of the code’s clauses specified that to receive exhibition permits, films could in no way, directly or indirectly, insult the prophet, the imams, the country’s supreme jurisprudence, or the leadership council. They could not encourage corruption, wickedness or prostitution, could not favor foreign culture, nor express anything that was against the interests and policies of the Islamic Republic. However, some clauses of the filmmaking code were less specific and more far reaching. The Board of Censors, for instance, could reject any film on the ground of encouraging “wickedness” or encouraging “foreign cultural influence” in Iran.

This situation changed overnight when Ezzatollah Zarghami was appointed as Cinema Deputy in 1996 and introduced what was considered a draconian code. In his book The Politics of Iranian Cinema, Saeed Zeydabadi-Nejadpoints out some of Zarghami’s edicts, which prohibited:

- • Unfavorable characters with names which have Islamic roots,

- • Criminals portrayed as sympathetic,

- • Closeups of women’s faces or their bodies except for hands above the wrist,

- • Women in tight clothing,

- • A multiplicity of costumes which could lead to a culture of consumerism,

- • Western clothing,

- • Actors smoking cigarettes or pipes,

- • Scenes in which someone is attacked with a weapon,

- • Body contact between men and women,

- • Negative portrayals of the armed forces, police, Revolutionary Guards, or People’s Basij, and

- • Using music similar to famous songs, both foreign and Iranian.

Many prominent directors at this time chose not to work or considered quitting filmmaking altogether. Some chose to continue their filmmaking elsewhere. Bahram Beyzai moved to France. Mohsen Makhmalbaf migrated to Canada.

In the 1990s, following a renaissance of Iranian cinema, a number of female film directors rose to prominence. Pouran Derakhshandeh, who started out making television documentaries, made her first film, Relationship, in 1986. Tahmineh Milani received critical acclaim for her 1991 film, The Legend of Sigh. Rakhshan Banietemad made movies such as the autobiographical, The May Lady, that addressed taboo subjects like divorced working mothers. Samirah Makhmalbaf, Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s daughter, made headlines with her debut film, The Apple, when she was only seventeen.

Jafar Panahi, a filmmaker influenced by Italian Neorealism, is renowned for making films about the marginalized classes of society. In 2010, he was arrested and imprisoned by the Islamic Republic of producing anti-government propaganda and was banned from filmmaking for 20 years. Since then Panahi has been released from prison but has been under house arrest and forbidden to leave the country. But ever-defiant Panahi didn’t stop working. One of his underground films, Taxi, won the Golden Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival.

“Iranian censorship,” The New York Times reported, “like Iran itself, is far from monolithic.” First, filmmakers have to submit their screenplays to the MCIG for approval before the shooting starts. After shooting, the final product again goes to the committee for review before being released to the public. The problem is, since these committee members are constantly changing, those who read a screenplay before it is made into a movie are seldom the same people who watch the finished product. “It’s like the weather,” director Asghar Farhadi explained. “In the morning, it’s sunny; in the afternoon, it’s cloudy. There isn’t a universal pattern or law.” But he also believes that “art in the face of censorship is like water in the face of a stone. The water will find a way to flow around it.” Farhadi who is a good friend of JafarPanahi, also said of the censorship process, “it’s claimed restriction can lead to even greater creativity. I believe that’s true in the short term, but in the long term it destroys creativity.”

Despite many ups and downs and strict regulations, over the past decades, Iranian films have attained global recognition. The BBC lauded Iran as having created “some of the world’s best films.” Critics at both the New York Film Festival and the Toronto International Film Festival have called Iranian Cinema one of the “most exciting” and “preeminent” national cinemas in the world. Iranian films have even broken through to the most recognized cinematic platform on the planet, the Academy Awards. Asghar Farhadi has won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film twice: A Separation in 2011 and The Salesman in 2016.

RAHAD ABIR is a writer from Bangladesh. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in The Los Angeles Review, The Bombay Literary Magazine, The Wire, Himal Southasian, BRICK LANE TALES Anthology, and elsewhere. He received the 2017-18 Charles Pick Fellowship at the University of East Anglia. Currently, he is an MFA candidate in fiction at Boston University and is working on his first novel.