Of Faith and Medicine

When Comic Book Muslims Go to the Hospital

A. David Lewis

A curious thing happens with Muslim characters in comics when they enter a hospital: they become somehow more Muslim. It is like a superpower, yet it occurs both in the superhero genre and beyond. That is, when a Jewish character enters a hospital in these works, their faith may or may not be mentioned; when a Christian character enters an E.R. or I.C.U. or Radiology Department, their particular religious affiliation usually goes unmarked. So, while the representation or depiction of Muslims is nicely on the rise in comics all across the U.S. market, it takes a curious turn when it comes to medical matters of life and death: it becomes a vital sign.

Examples aren’t numerous but they are largely consistent. Only a few mainstream comic book titles and graphic novels feature Muslim characters, and still fewer headline them. Fortunately, their number is increasing yearly, and their storylines, likewise, are multiplying. Since my research focuses on how religion and medicine each engage comics, I take keen note when they all overlap. Therefore, what might feel like an isolated narrative device can sometimes be seen as a trend if monitored by a motivated scholar.

Take, for instance, the book Lissa: A Story about Medical Promise, Friendship, and Revolution (University of Toronto Press, 2017) where two childhood friends, Anna and Layla, encounter sharply different medical considerations in their respective countries. Anna is an American girl and carries the BRCA genetic mutation that contributed to her mother and aunt’s deaths from breast cancer; she undergoes her own journey through the U.S. healthcare system and the choice of prophylactic double mastectomy without a word being said as to her religion or faith. Comparatively, Layla’s father is experiencing kidney failure in Cairo, and his beliefs appear prominent in his decision not to accept a transplant from either of his children. “God, in His Perfect Wisdom, created us whole… We cannot give away what is not ours to give,” he says. Even Layla’s mother echoes this, noting, “Life flows from the old to the young… not the other way around.” This perspective is not shared by the medical community, some of whom sneer at these “ignorant peasants” for delaying care. The disparity between the religiosity in Anna and Layla’s circumstances could be attributed to a number of factors, not the least of which being that Lissa was the product of ethnographic research and built on stories and observations of real-life cultural experiences.

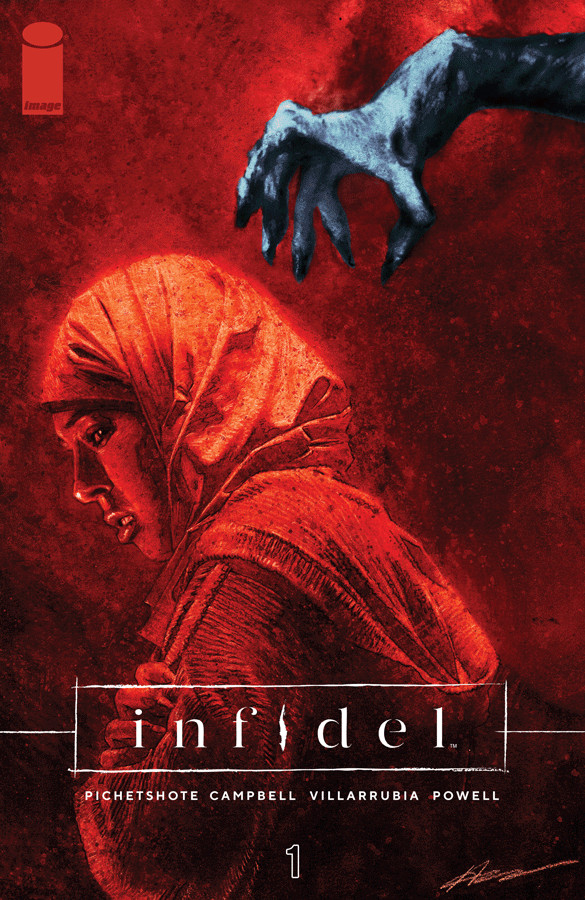

However, Lissa marks an imbalance to which a work like the award-winning Infidel (Image Comics, 2018) adds further weight. In this horror story of a cursed apartment building driving its tenants either mad, homicidal, or both, Medina goes to visit her best friend Aisha in the hospital; the latter alternates between seizures and comas due, it seems, to the trauma of having lived in the apartment complex. Whereas Medina “ditched all things Islam at fourteen,” she stands above her bedridden friend and asks herself, “If you were me right now, what would you do?” With that, the self-professed cynic washes her hands, stares at herself in the mirror, and kneels next to Aisha to pray the surah al-fatiha. It is a touching moment but, again, not something any of the non-Muslim characters do anywhere in the book, much less the hospital setting. In fact, it is the only moment of prayer or outright religious action in the book by anyone other than Aisha.

(from Infidel)

It is debatable whether Medina’s prayer directly aids Aisha — the latter recovers while the former sacrifices herself to stop the building’s evil — but in the Green Lantern series, one Muslim can accomplish the miraculous in a hospital room. Though Michigan-native Simon Baz is brand-new to the superhero life (i.e. this is 2013’s issue #16, just months after his debut), he can do something with the cosmically empowered Green Lantern ring that none of its wielders ever could previously. Due in part to his own recklessness, Simon’s brother-in-law and best friend Nazir lays unresponsive in the hospital bed. Through the tears, Simon tells his sister, “I’ve seen the unthinkable over the last two days, Sira. Magic rings. Flying men. Aliens. I refuse to believe the ring can’t help Nazir.” Then he does the impossible: Witnessed by the vetern Green Lantern B’dg, Simon pushes his ring to its limits and somehow heals Nazir. It should have been beyond the ring’s abilities — “It cannot raise the dead. Or cure any ill,” says B’dg — but Simon accomplishes it through faith. “I believed, Sira. For a moment, a brief moment, I believed I had the chance to make things [right].” Nazir awakens, and B’dg must take back his words: “Maybe the ring did choose you for a greater purpose. Maybe you are a greater part of this than I’d ever imagined.” Maybe the Green Lantern Corp never had a Muslim member before.

Finally, there is a quieter but no less potent moment in The Magnificent Ms. Marvel that further exemplifies this trope. In 2019’s issue #9, the title character, in her civilian identity as Kamala Khan, sits in the Jersey City Medical Center with her family. They await news on her father whose rare illness had suddenly taken a turn for the worse, requiring his emergency transfer to the hospital. A supervillain will appear soon enough, and the story will return to its expected adventurousness, but in this moment, Kamala engages in a threefold rarity for the book: She says she needs to pray, she ruminates over God by name, and she admits her anger with God as well. This is not to suggest that Kamala, like Medina, is herself a cynic nor wholly secular; quite the opposite, the creators behind Ms. Marvel have worked to imbue her with deep ethics gained from her familial culture and with a strong religious identity. Unlike Lissa, Infidel, or Green Lantern, however, this is something of a non-visual moment. The panel zooms in on Kamala’s knitted brow and eyes partly obscured by her bangs, but there is no action or even discussion of which to speak. It is largely textual and isolated. What makes this Muslim-in-a-hospital moment additionally curious is how pronounced Islam and her feelings on the divine are. What has always been at the character’s core rises strangely to the surface: subtext becomes stated.

(from The Magnificent Ms. Marvel)

Undoubtedly, hospitals and healthcare facilities, in real-life as well as in fiction, are places of high drama and intense feeling. Medical settings can bring the issues of mortality, family, belonging, existence, and dogma into sharp relief, challenging all of them as much as they may also reify them. Therefore, it is not odd that a Muslim character would think or call on their religion in such an instance, for that impulse is highly relatable to audiences, regardless of belief system.

The question that remains here is: Can audiences accept a Muslim character who doesn’t look to Islam in a moment of medical crisis? Anna does not overtly think on her faith — if she even has one — when electing for her surgery, and B’dg does not invoke any alien, galactic theology when looking to aid Simon. Other characters across these genres of comics may or may not tap into their spiritual convictions at such a moment, but Muslim characters seem required to do so.

They must demonstrate their Muslim-ness, preferably in action but at least in words, lest it be found wanting. Alternatively, the other remedy here would be to trust in a Muslim character’s faith, displayed or otherwise, the same as we might with a non-Muslim one. The inclusion of Islam in comics and these narratives is an entirely welcome thing; a compulsory performance of it, even during a life-and-death scene, is not.

Dr. A. DAVID LEWIS is a comics studies scholar and co-editor of Muslim Superheroes: Comics, Islam, and Representation. He is full-time faculty at MCPHS University, specializing in Graphic Medicine, where he explores the representation of cancer in comic books and graphic novels.