Pandemic Theater

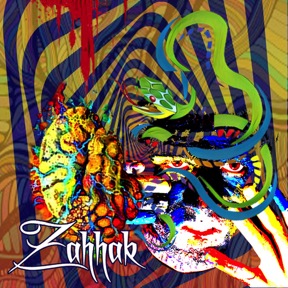

Zahhak: The Legend of the Serpent King

Sassan Tabatabai

In December 2019, Mizan-PoP brought you the story of “Last Dream,” a play staged by the Boston Experimental Theater Company (BETC): https://mizanproject.org/pop-post/theater-of-activism/.

In what was described as “theater of activism,” BETC produced a play about a group of US-born Salvadoran children from Temporary Protected Status (TPS) families who were facing the prospect of having their parents deported following Donald Trump’s rescission of TPS for El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Nepal, Nicaragua and Sudan in January 2018. The production put thirteen children ranging from 9-17 years old at center stage, who in collaboration with BETC, became intimately involved in every aspect of the play, including the creation of a storyline and set design.

The newest project by the Boston Experimental Theater Company is “Zahhak: The Legend of the Serpent King,” based on Ferdowsi’s 10th century Persian epic, Shahnameh (Epic of Kings). What “Zahhak: The Legend of the Serpent King,” and “Last Dream” have in common is that both plays are largely informed by the current historical environment in which they were created. The backdrop of “Last Dream” was Donald Trump’s rescission of TPS, which was meant to provide temporary protected status for immigrants from designated countries unable to return home, and affected approximately 200,000 Salvadorans who could face deadly violence if they were to go back to El Salvador. The contextual background for “Zahhak: The Legend of the Serpent King,” which can be designated as “pandemic theater,” is the covid-19 pandemic that spread across the globe starting in early 2020.

Production on BETC’s “Zahhak” project began in 2020 with Vahdat Yeganeh directing, Donya Pooli-Yeganeh acting, and Engin Ozsahin playing the piano. But the goal of having a live performance in April of the same year was scrapped because of the pandemic and in-person rehearsals were cancelled and moved online. The trio continued rehearsing online for the next few months and met in person for one week in July and filmed the production in one take as if it were a live performance. Shortly after, “Zahhak: The Legend of the serpent King” was released on YouTube with the aim of making it accessible to audiences around the world, who could watch it in the safety of their homes during a difficult time of lockdown and isolation.

In the Shahnameh, Zahhak, who has usurped the throne of Iran, is an evil king with two black snakes growing out of his shoulders. Everyday, two young men must be sacrificed and their brains fed to the snakes on Zahhak’s shoulders. Zahhak, who reigns for 1,000 years, is an emblem of the evil despot who would literally consume his own population. His story is one that resonates outside the realm of myth with real-life characters throughout human history. At two heads a day for a thousand years, Zahhak consumed over 700,000 people. This is a number that pales—in the past century alone—before the millions consumed by the voracious appetites of the Hitlers, Stalins, and Pol Pots of this world.

“Zahhak: The Legend of the Serpent King” is an adaptation of Ferdowsi’s story that attempts to study the philosophical, psychological, and political relation of the myth to ourselves, in our own times.

What is unique about this play is that its development and production were devised and based largely on improvisations during the online rehearsals. At the core of the drama was the tight-knit dynamic between director, actress and musician with much of the music, acting, and even lighting being improvised as the play was being filmed.

This surrealistic adaptation of Ferdowsi’s story is grounded—like many of BETC’s other productions—in Antonin Artaud’s psychological philosophy of the relation between performer and audience, which seeks to move beyond the words of the performer and connect with the emotions of the audience. And true to BETC’s mission to create a dialogue between cultures, the production is strongly inspired by the traditional Persian story telling performances known as “Naghali,” the concept of “free jazz improvisation,” and Jerzy Grotowski’s notion of “poor theatre,” a theater that puts the body of the actor and its relation with the audience at center stage.

This play, produced during the height of the pandemic, is a unique theatrical enterprise inspired by both western and eastern theatrical traditions, and rooted in the organic connections among artists working within a minimalist production design.

You can watch “Zahhak: The Legend of the Serpent King” bellow:

SASSAN TABATABAI is Guest Editor of Mizan-Pop.