PDF

Download

Citations

Click and drag then release to select a passage to cite.

Annotations

How to submit annotations to Mizan Journal articles:

your work is published.

Search within

Solomon Legends in Sīrat Sayf ibn Dhī Yazan

Image

Audio

Video

Chart or Graph

Solomon Legends in Sīrat Sayf ibn Dhī Yazan

Introduction

Sīrat Sayf ibn Dhī Yazan (“The Adventures of Sayf b. Dhī Yazan”) is a late-medieval Egyptian popular epic that recounts the story of the life and adventures of King Sayf b. Dhī Yazan, son of the Yemenite king Dhū Yazan.1 Set against the background of a war with the king of Ḥabash,2 Sayf Arʿad, it tells the story of how Sayf b. Dhī Yazan (henceforth “Sayf”) leads his people into Egypt, diverts the Nile to its current course, and then goes on to conquer the realms of men and jinn in the name of Islam. Set in legendary pre-Islamic time, it rewrites history to present Egypt as born out of a “reverse exodus” led by a proto-Islamic, Yemeni king.3 As is common in Arabic popular literature, Sīrat Sayf draws much of its material from a pool of popular and folkloric story patterns, motifs, and tropes, which are pieced together in a unique way so as to tell its story. It also makes intertextual reference to stories, legends, and other narratives in ways that enrich the thematic subtext and convey meaning. From this perspective, references to the Islamic qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ (“tales of the prophets”) play a significant role in the text. Not only do they anchor the proto-Islamic world of Sīrat Sayf in Islamic legendary world history, but the associations they bring into the text also nuance the characterization of Sīrat Sayf’s main protagonists and help to create subtextual and thematic complexity.

This article investigates a number of direct references made to legends about the prophet Solomon within Sīrat Sayf in order to explore how this particular sīrah uses the “Solomon” intertext and to what end.4 It focuses primarily on two particular episodes in the sīrah, during both of which stories about Solomon and the Queen of Sheba are recounted by characters within the text. After introducing these stories in the first section of this article, the second section assesses the intertextual relevance of the Islamic Solomon legend to Sīrat Sayf. It analyses how these stories, and the episodes in which they are embedded, relate to the Solomon legends as found in premodern qiṣaṣ sources, and how Sīrat Sayf uses intertextual reference to Solomon legends to express its own thematic agenda. In a previous study, I have argued that Sayf is, at its core, a discussion of kingship, fitness to rule, and the importance to society of keeping the forces of order and chaos in balance, and that it expresses this struggle largely through the literary use of gender (according to which, broadly speaking, the female embodies the forces of chaos, and the male the forces of order).5 The use of intertextual reference to other narratives is a key element of this discussion. The final section explores the intertextual relevance of the Ethiopian story of Solomon, Bilqīs, and their son Menelik found in the Kǝbrä Nägäst to the Sayf text.

The prophetic intertext in Sayf tends to take one of three basic forms. First, there are accidental, or optional, intertextual associations. These are created when, either consciously or unconsciously, storytellers incorporate a variety of tale patterns, themes, and motifs which, however commonly found in Arabic popular texts, have strong associations with various qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ or the Sīrah nabawiyyah, the life of the Prophet Muḥammad. For example, Sayf’s overall character trajectory has notable echoes of the character trajectory of the Prophet Muḥammad as recounted in the orthodox Sunni sīrah tradition. To mention just a few correspondences: both Sayf and Muḥammad rely on foster mothers during their infancy and are subsequently brought up by foster fathers; both discover their heroic identity and destiny through encounters with cave-dwelling ascetics; in both cases the first person they convert is their wife (Muḥammad’s first convert to Islam was Khadījah, his first wife, whilst Sayf’s first convert is Nāhid, who later becomes his second wife). At a more global level, both Sayf and Muḥammad lead their people on a hijrah (emigration), are lawgivers to their respective communities, and engage in expansionist conquests in the name of Islam. Because Muḥammad is the ultimate Islamicate hero, and his heroic pattern is one that is echoed in a great many other narratives, it is impossible to categorically state whether these parallels exist because the narrator/author of Sīrat Sayf was deliberately referencing Muḥammad’s life story, or if the similarities between the two heroes exist simply because Muḥammad’s heroic progression expresses the ultimate Islamic heroic pattern.6

In addition to these accidental references, Sīrat Sayf contains a number of direct (or obligatory) intertextual references to legends and tales about prophets and religious figures that are recounted to one character by another. These stories (or pretexts7) are often ostensibly told to explain the presence of a particularly significant relic or occurrence. For instance, in the introductory section of Sīrat Sayf, which sets the stage and relates how Sayf’s father (Dhū Yazan) and his mother (Qamariyyah) met and married, Dhū Yazan stumbles across the Ka’bah during a military expedition. As he marvels at the sight before his eyes, his learned vizier Yathrib, who has read predictions of the coming of Muḥammad and Islam from his reading of ancient books, tells him the story of the Ka’bah’s creation and related tales about Adam and Noah.8

These recounted tales often also serve a more significant purpose, acting as literary devices that inform plot, characterization, theme, and meaning. For example, the story of Noah’s cursing of his son Ham found in Noah legends is told repeatedly by various characters to one another throughout the sīrah, where it is accompanied by predictions that Sayf will be the one to implement the curse, that the descendants of Ham would be the slaves of the descendants of Shem.9 The story of Noah’s curse thus functions as a narrative device that drives the entire plot of the sīrah: when the Ḥabashī king, Sayf Arʿad, learns of Dhū Yazan’s existence he is warned by his advisors that one of his line will bring about the curse and take his throne, and the Ḥabashī’s subsequent determination to avert the implementation of the curse and destroy Sayf underlies the events of the entire sīrah.

Finally, the names of prophets are associated with various magical weapons or talismanic objects discovered by the sīrah’s heroes. Such relics act as “emblems of identification,” and are devices by which the nature and character of the hero are denoted to the audience.10 In Sīrat Sayf, Sayf inherits two swords. The first, the sword of Shem, is left to him by Shem, Noah’s son, in the early stages of the sīrah. It is later supplanted by the sword of Āṣaf, which is left to Sayf by Āṣaf b. Barakhyā, Solomon’s vizier, who created it expressly with Sayf’s future needs in mind.11 The sword of Āṣaf is a mighty weapon which has been enchanted by Āṣaf to protect its bearer against attack by the jinn. Not only this, but it can kill any type of jinn, and can also be used to test the sincerity of conquered converts: when laid upon the neck of an unbeliever it slices off his head or wounds him horribly, but a true Muslim remains unharmed.12

Solomon stories in Sīrat Sayf

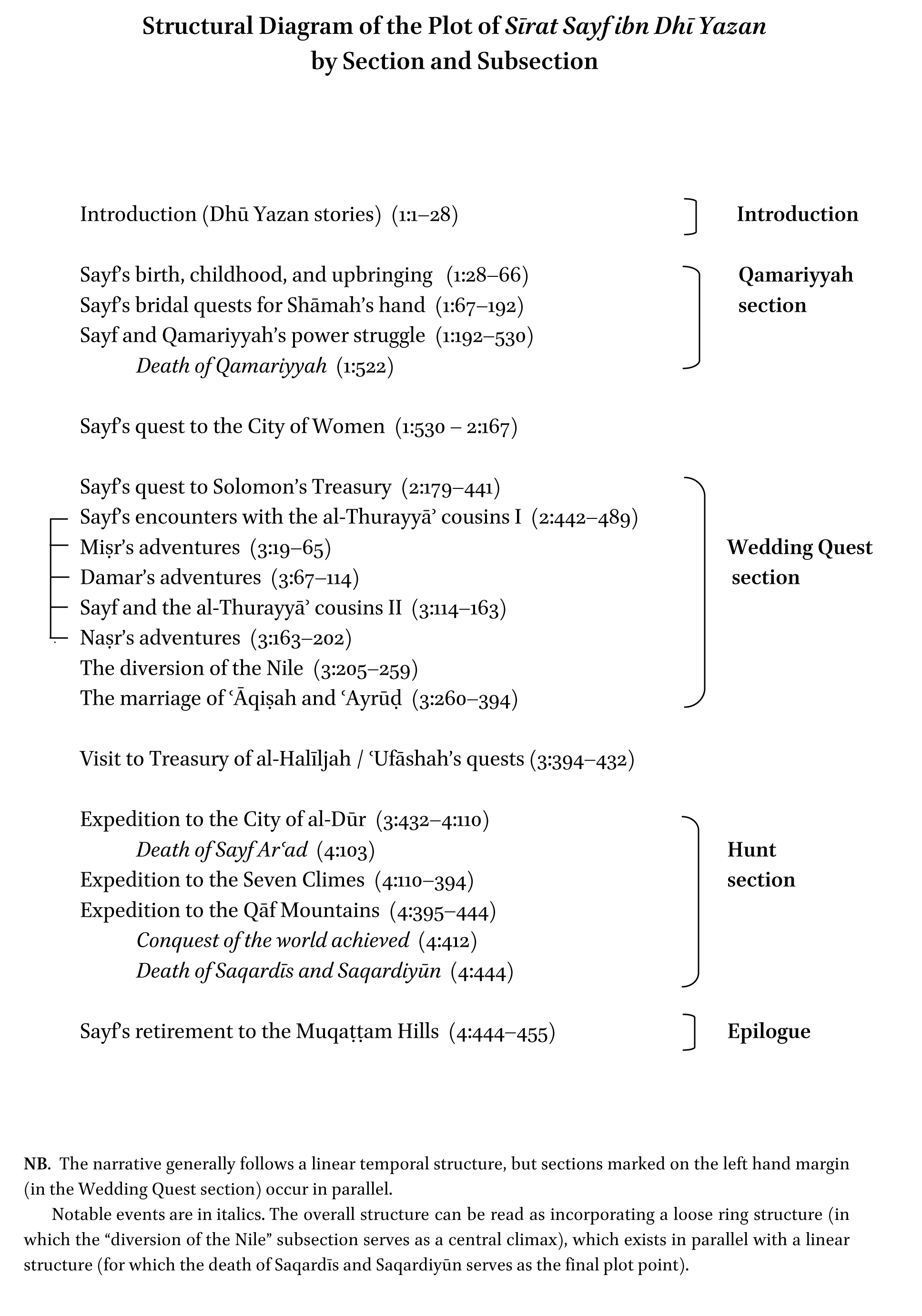

Sīrat Sayf falls naturally into four parts (see Diagram A): (i) a short introduction in which Dhū Yazan leads his people out of Yemen and founds Madīnat al-Ḥamrāʾ (“The Red City”) in Ḥabash, unwittingly triggering a war with the Ḥabashī king; (ii) the “Qamariyyah section,” which relates Sayf’s birth and childhood, and his conflict with his mother for the throne after his father’s untimely death; (iii) the “Wedding Quest” section, in which the Ḥabashīs destroy Madīnat al-Ḥamrāʾ and Sayf leads his people to Egypt, diverts the Nile, and founds the city of Miṣr (Cairo); and (iv) the “Hunt” section, in which the (now) Egyptians go on the offensive, defeat the Ḥabashī king, Sayf Arʿad, and chase his advisors, the evil magicians Saqardīs and Saqardiyūn, through the human world and the realms of the jinn, conquering and/or converting every people they meet.13

The Solomon intertext is entirely absent from the first of the main sections of Sīrat Sayf, which references stories of the more ancient patriarchal founding fathers such as Adam, Noah, and Abraham, but it plays a key role in the second section, the Wedding Quest section. This section contains a plethora of references to Solomonic legend, but there are two particular, related episodes in which Solomon is referenced that will be addressed here. The first occurs at the beginning of the Wedding Quest section, and occurs as part of its frame story, the problematic betrothal and marriage of two of Sayf’s closest companions, ʿĀqiṣah and ʿAyrūḍ.14 The second occurs in the middle of the Wedding Quest section, at the beginning of the Nile Diversion subsection that comprises the central climax of the section and the sīrah overall.

Episode 1: the frame story of the Wedding Quest section

The Wedding Quest section takes as its frame story the betrothal and marriage of two of Sayf’s closes allies, Sayf’s jinn milk-sister, ʿĀqiṣah, and his jinn servant and friend, ʿAyrūḍ. The section begins when ʿĀqiṣah, determined to extricate herself from an unwanted marriage to ʿAyrūḍ (to whom she has been promised by Sayf), requests Bilqīs’s bridal clothes from the treasury of Solomon as her dowry:

Sayf b. Dhī Yazan said, “ʿĀqiṣah, tell me what you request,” and she replied, “I ask of ʿAyrūḍ the crown, the diadem, the belt, and the bejeweled wedding dress which the Lady Bilqīs wore when she married the prophet Solomon, son of David. If he is capable of bringing me these things, I will be forever in his service, and I will be his bedfellow and hear and obey.”15

The entire court is shocked and dismayed by this request, as it is well known that the treasury is closely guarded by a fearsome contingent of jinn, appointed by the great king himself, who are under orders to eliminate any would-be intruders. Despite all their efforts to dissuade her, ʿĀqiṣah remains adamant that she will not marry without these gifts and, amid much lamentation, ʿAyrūḍ departs on his quest to the treasury, only to be captured and cruelly tortured by the jinn as soon as he arrives. When Sayf realizes that ʿAyrūḍ is in trouble, he sets out to rescue both him and the dowry. After many diverting adventures en route, he eventually reaches the mountain on which the treasury is situated, where he finds an enchanted pool containing magical brass fish:16

Sayf continued on his way until he found [the pool he had been told to look out for]. He gazed at it, and saw that in it were fish made of red, yellow, and white brass, which were frolicking in the water like normal fish. King Sayf was astonished by this, and exclaimed, “God is indeed Almighty!” He said to himself, “I wonder if this was done by magical means, or if Almighty God did this?” He was still considering this, and marveling at [the fish] when a stranger approached…17

After greeting the stranger, Sayf asks him about the fish, and the stranger tells him:

“The Prophet Solomon, when he married the Lady Bilqīs, was deeply in love with her and built a castle for her over the treasury [raised up] on forty pillars of white and red marble. He labored on this castle until it enchanted everyone who looked upon it. And when he had finished building it and decorating it, the Lady Bilqīs said to her husband, the prophet Solomon, ‘Sir, the decoration of this castle is not complete. To be finished, it needs a marble fountain at its center, full of flowing water, so that one can stroll around it.’”

The stranger goes on to tell Sayf of how Solomon agreed to this demand, and ordered the jinn to build the fountain, and created a pleasure garden around it, full of all kinds of birds and animals. The jinn were set to work operating the pumping mechanism that kept the water flowing, but the task was so arduous that they began to die. The king of the jinn then went to Solomon and told him that only a particular jinn, al-Rahaṭ al-Aswad (“the Black Gobbler”), was strong enough to work the pump. On hearing this, Solomon sent his vizier, Āṣaf b. Barakhyā, to al-Rahaṭ with a letter summoning him to his presence.

One day, after al-Rahaṭ had been put to work, Bilqīs and Solomon were sitting by the fountain and she asked him to fill the fountain with fish, but told him that she would like the fish to be made of silver, gold, brass, and other precious metals. Solomon ordered al-Rahaṭ to make the fish, and after he had done so, jinn were sent inside them to animate them so that they moved like real fish. However, Bilqīs was not satisfied by this, and asked that the fish be made truly alive, able to mate and breed. Solomon immediately prayed to God, his request was answered, and the fish came to life. Solomon was so awestruck by this that he enchanted the fountain with powerful enchantments to ensure that the fish would always remain there and no one could either drink or take anything from it. Finally, he appointed the stranger, Shaybūb, as its guardian to watch over it for all time.

After listening to this story, Sayf spends the night by the enchanted pool resting. When he finally makes it to the treasury, he discovers that his arrival has been prophesied by Bilqīs. Aware of Sayf’s future need of her wedding robes, she has left instructions with the jinn guardians of the treasury that he should be helped in his quest:

[The guardians’ leader] Kayhūb told him, “If you speak the truth [about who you are], then your desires will be fulfilled without obstacle, for when the Lady Bilqīs placed these garments in the treasury, she entrusted us with their care and told us, ‘Protect these garments until a stranger comes to you, travelling far from his lands and people. You will find him short and pale skinned, and he will have a green mole on his right cheek and be girded with various swords. He will tell you that his name is Sayf b. Tubbaʿ b. Ḥassān, and his lineage goes back to the Ḥimyarites. Give him the gown, for I bequeath it to him as it is the finest thing that I own in the treasury.’ I asked her, ‘My Lady, how will we know if he is honest or lies?,’ and she told me, ‘When the time has come, and this young man comes here, bring him to the door of the treasury and tell him to recite his lineage. If it is truly him the doors will open for him, and he is the rightful owner, but if the door does not open for him, know, Kayhūb, that he is a liar, so kill him and bury him in the ground.’”18

Once the dress and crown have been retrieved and ʿAyrūḍ rescued, the two companions set out on their return journey. On the way, they stop again at the enchanted pool and Shayhūb temporarily lifts the enchantment to allow ʿAyrūḍ to heal his wounds by drinking from it, as its waters have magical healing powers. ʿĀqiṣah, who is still determined not to marry ʿAyrūḍ, turns up several times as they begin their homeward journey to argue with Sayf about her proposed marriage and demand he hand over the robes and crown to her. On one occasion she goes so far as to steal the sword of Āṣaf from him, and throws it into the sea when he will not give way to her demands.19 Sayf and ʿAyrūḍ are sidetracked by many adventures on their homewards journey, but when they do eventually reach home with her dowry, ʿĀqiṣah is still unimpressed. She flounces off to her parents’ home in the Qāf mountains, saying that she refuses to marry a slave and an incompetent who has to be rescued.20

The theme of ʿĀqiṣah and ʿAyrūḍ’s marriage takes a back seat following the quest to Solomon’s Treasury while the sīrah moves on to recount the adventures of Sayf and his sons Damar, Miṣr, and Naṣr for the next two hundred and fifty pages. Sayf is captured and imprisoned by an evil queen, al-Thurayyā al-Zurqāʾ, who transforms him into a bird and keeps him in a cage, while his sons are each abducted by jinn on the orders of an evil magician and abandoned in faraway lands. Eventually, Sayf’s sons all make their way home, and Sayf himself is rescued and reunited with his family and his people. However, in his absence, the Ḥabashīs have sent an army against Madīnat al-Ḥamrāʾ and the Yemenites have been forced to flee their city, which was then razed to the ground. Homeless, Sayf makes the decision to lead his people out into the arid wastes of Egypt—then a waterless desert inhabited by only a few magicians—on an exodus to find a new home.

On arriving at an oasis, Sayf decides to settle his people there. However, word soon spreads and as more and more people arrive and their numbers put pressure on the existing supplies of water, Sayf is reminded by his advisors of the predictions that he will divert the course of the Nile. The ensuing subsection, the Diversion of the Nile, is both the climax of the Wedding Quest section and the central climax of the whole sīrah,21 and is followed by a long subsection in which the narrative focus returns to ʿĀqiṣah and ʿAyrūḍ’s betrothal. Despite the fulfilment of ʿĀqiṣah’s dowry demand at the beginning of the Wedding Quest section, she remains stubbornly opposed to her marriage, in the face of all efforts to persuade her, until ʿAyrūḍ proves himself to her as a worthy suitor. Their eventual marriage closes the frame story and marks the end of the Wedding Quest section.

Episode 2: the Diversion of the Nile

The Solomon intertext is clearly integral to the frame story of the Wedding Quest section. In addition to this, it plays a role in the Nile Diversion subsection. In order to divert the Nile, Sayf needs seven magical items: the Book of the History of the Nile, the sword of Āṣaf, the emerald horse Barq al-Barūq al-Yāqūtī, the pick of Yāfith b. Nūḥ (Japheth), the talisman of Kūsh b. Kinʿān, the talisman of al-Khīlijān and al-Khīlikhān, and al-Rahaṭ al-Aswad.22 Sayf already has most of these, but is told by his advisors that he must locate and enslave the black jinn, al-Rahaṭ, as only he is strong enough to carve out the course for the new river with Japeth’s pick. Sayf appears to have forgotten the story he was told about al-Rahaṭ at the beginning of the section, when he came across the pool of enchanted fish during his quest to Solomon’s Treasury, and asks his advisors who this al-Rahaṭ is and where he can be found. In response, the sorceress ʿĀqilah, one of Sayf’s senior advisors, tells Sayf the strange tale of how al-Rahaṭ came to be imprisoned by Solomon as punishment for having the audacity to fall in love with Bilqīs. As we will see below, her account includes a slightly different version of the fish story.

The inclusion of ʿĀqilah’s story at this point of Sīrat Sayf serves to bring Solomonic associations into the text at this critical, climactic point of the text. These associations are pertinent partly because at this point in the narrative Sayf has embarked on a massive building project: the establishment of the new capital city of Miṣr which necessitates the diversion of the river Nile. The king is reliant on the labor of his jinn servants for both of these undertakings, just as Solomon was reliant on jinn to build the Temple of Jerusalem.23 However, the Solomon/Bilqīs intertext brought into the text at this point plays a more complex role than simply providing connotations of divinely-sanctioned building. The story ʿĀqilah tells here is much more detailed, and much longer than the previous account, and contains a notably different account of the way in which the enchanted fish are brought to life. This more developed account resonates intertextually with the events and themes of the Nile Diversion subsection in various ways. It is also significant that Sīrat Sayf is here making internal intertextual reference to itself by repeating the fish story at this particular point: the reintroduction of this relatively small anecdote at the beginning of the Nile Diversion subsection reminds the reader of past events, and of the plot device of ʿAyrūḍ and ʿAqiṣa’s betrothal, thereby bringing the subtextual, thematic symbolism of their relationship back into play.

According to the version of this story told by ʿĀqilah, after their marriage, Bilqīs asked Solomon to build her a castle on pillars, which he dutifully did. The end result was truly amazing: built of bricks of gold, silver, and precious metals, it had a central fountain forty feet high and forty feet deep. Bilqīs, however, was not quite satisfied, and asked for some fish for the fountain. Solomon ordered his jinn to fetch some fish, but Bilqīs rejected these as being too commonplace, and asked for some special fish that were not to be found anywhere else, and which were to be made of gold and silver. Solomon had the jinn make four fish, two of gold and two of silver, and these were placed in the fountain.

However, when Bilqīs inspected the fountain she was disappointed that the new fish didn’t move and asked Solomon to make them behave like real fish. Solomon acquiesced, and ordered some jinn to enter the fish and animate them. Bilqīs, still unsatisfied, informed her husband that what she really wanted was fish that actually seemed to be alive and were capable of breeding, rather than fish possessed by jinn. Solomon, after agonizing over the possibility that this essentially fatuous request might well call down divine wrath upon his head, prayed to God to perform this miracle for him. Rather than immediately granting his request, as He did in the previous version of this story, in ʿĀqilah’s variant God’s response to Solomon’s prayer is to send down the angel Gabriel with the message that his request would be granted on one condition: that everyone present truthfully state their most secret jealousy.

No sooner had he [Solomon] ceased praying than the angel Gabriel descended, and said to him, “Prophet of God, your Lord bids you peace and says, ‘Know that there are four fish and that four of you are present. Each of you must reveal your secret envy (ḥasad) and speak of their inner resentment (mā fī qalbihi min al-kamad), so that you will become aware of [the secrets] harbored among you. For each of you who is truthful—and God knows if you speak truly—I will bring one fish to life.’”24

The vizier Āṣaf, Āṣaf’s father, Solomon, and Bilqīs were all present, and confessed in turn. As they did so each fish was miraculously brought to life. Āṣaf’s father admitted that he was jealous of his son’s knowledge of the sciences and the magical power of books, while Āṣaf confessed that he envied his master, Solomon, because while he himself had to struggle for 121 years to attain his wisdom and knowledge, God gave Solomon knowledge and the Ring of Power, which gave him dominion over men and jinn. It then emerged that Solomon’s secret envy was of the power Bilqīs had over him:

Lord Solomon said, “As for me, I envy my wife Bilqīs, and the reason for this is that God has given me power over the multitudes of His creation, and rendered [even] those with wisdom and knowledge subject to my rule, but this Bilqīs rules over me. Men follow my command, but I follow hers.”25

Bilqīs’s envy, we then discover, was of the virile power of young men:

The Lady Bilqīs said, “Of all men, I secretly envy those whose cheeks are soft like mine, and whose cocks are as thick and strong as my forearm, who burrow and slam, and who are not hampered by any illness or affliction. This is what pleases me, and there is nothing better: I don’t desire anything else, nor will I accept it!”26

Despite the miraculous fish, however, the queen’s demands were not at an end: she next requested that her husband arrange that the water level in the fountain remained constant and never fell. After consulting with Āṣaf, Solomon ordered the jinn to make a pump so as to ensure the water supply. Unfortunately, as the castle was high up on a mountain, and the water source far away, every day some of the jinn working the pump died of exhaustion. The jinn sent a delegation to complain to Solomon, who again consulted Āṣaf. The vizier told him of al-Rahaṭ, a mighty mārid27 who would be able to work the pump alone, so Solomon captured him and put him to work. Al-Rahaṭ, finding himself trapped inside the column which housed the pumping mechanism, resigned himself to his fate.

Soon afterwards Bilqīs decided to inspect the pumping mechanism, curious to see how it worked, and al-Rahaṭ, not realizing who she was, instantly fell in love with her. The next day, as coincidence would have it, Āṣaf and Solomon also visited him and the mārid asked if he might marry the beautiful woman he had met the day before. Solomon initially agreed, but when he found out that the woman in question was Bilqīs, he was overcome with rage, and was only prevented from killing al-Rahaṭ when Āṣaf intervened and told him that the mārid would be needed by King Sayf in future times:

The prophet became enraged when he realized that [the object of al-Rahaṭ’s desire] was his wife, and he wanted to stamp his seal on [Rahaṭ’s] forehead so that he might perish from the inscription on the ring, but the vizier said to him, “Have patience, O Prophet, soon a tubbaʿī king will be born who will populate the land after destruction and death, and this al-Rahaṭ will carry the pick of Japheth, the son of the prophet Noah, and with it will cleave through the cataracts, destroying them, and the waters will flow through them and carry the river Nile through the farthest reaches of the land. This king will be called Sayf. Carving through the rapids and the cataracts will be difficult for him, and he will not be able to achieve it without al-Rahaṭ.”28

Upon hearing this, Solomon relented and sent al-Rahaṭ to another palace, where he was imprisoned inside a pillar of iron to await the coming of the Yemenite king.

Sīrat Sayf and Islamic Solomon legends

It is immediately apparent that the episodes described above both refer to one aspect of the Solomon legend, his relationship with the Queen of Sheba (and this holds true for most of the references to Solomonic legend made in this variant of Sīrat Sayf). A vast collection of tales has been built up around the figure of Solomon over time in the Islamic tradition. However, there is thematic coherence to these tales, many of which demonstrate Solomon’s great wisdom, often through his ability to discern the difference between outward appearance (zāhir) and inner reality (bāṭin). In most major works in which the tales of the prophets are collected, the Solomon legend is given coherence by a number of core episodes which tend to appear in an accepted order, as in all of the qiṣaṣ accounts I have consulted here. These core episodes provide a basic narrative framework, on which is hung a host of other anecdotes that vary widely between collections.29

The Solomon legend consists, then, of anecdotes describing the wealth, wisdom, and judgment of Solomon, his magnificent throne, his God-given power over animals, the jinn, and the winds (which he uses to transport his vast army through the air), and his military prowess. There is also a corpus of animal tales that elaborate on Solomon’s wisdom and humility.30 Examples of these often preface the three more established stories of the Solomon cycle. The first of these is the story of Solomon and Bilqīs, the Queen of Sheba, in which the queen visits Solomon at his request, the two test each other’s wisdom, and Bilqīs finally admits Solomon’s superiority and submits to him.31 This is usually followed by the story of Solomon and Jaradah, in which God causes Solomon to temporarily lose his throne and ring of power to a jinn, Ṣakhr, as punishment for allowing one of his wives, Jaradah, to commit idolatry.32 The final episode is the account of Solomon supervising the building of the Temple of Jerusalem, during the course of which he dies, but remains leaning on his staff so that the jinn, who are terrified of his wrath, continue their work.33 The core Islamic Solomon legend can thus be defined as consisting of four specific elements: (i) initial stories demonstrating the king’s wisdom and might, (ii) his battle of wits with the Queen of Sheba, (iii) the loss of his throne to the jinn Ṣakhr, and (iv) the account of his death whilst building the Temple.

It is immediately clear that the Solomon stories told within Sīrat Sayf summarized above do not reproduce material from the Solomon legend discourse as found in the major qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ works. In contrast, the story of Noah’s cursing of Ham, which is told repeatedly by various characters in the early stages of the sīrah, is clearly the same story as told in the canonical qiṣaṣ collections. The stories told about Solomon and Bilqīs in Sīrat Sayf are conceptually linked to the stories found in the qiṣaṣ, but they are not stories that are familiar to us from these accounts.

Having said that, although Sīrat Sayf does not replicate Solomon material found in the written qiṣaṣ collections, it is evident that without familiarity with the wider Solomon intertext much of the import of the Solomon stories told in Sayf would be lost. For example, the story about the enchanting of the fish and the imprisonment of al-Rahaṭ recounted in the sīrah by ʿĀqilah becomes more complex and meaningful if one is aware of the story of Solomon and Bilqīs’s power struggle as told in the mainstream qiṣaṣ tradition. Familiarity with the “Solomon” pretext of the story of Bilqīs’s journey to see the prophet-king and their battle of wits, in which Solomon seeks the submission of the queen, nuances how we read the interaction between Solomon and Bilqīs in Sīrat Sayf. Likewise, when ʿĀqiṣah hurls Sayf’s sword into the sea, her action becomes more threatening because she is associated with the Solomon intertext in such a way that it resonates of the theft of Solomon’s ring of power, which is likewise thrown into the sea, by Ṣakhr. The narrator/author is playing with their audience’s knowledge of the qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ and manipulating the legend corpus for their own ends; they are twisting the story so that it becomes a vehicle for the themes that are being discussed in the sīrah, but they are also apparently making up (or at least making use of) a Solomon story that exists outside the Islamic legend corpus as it is found in the qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ. So, why does the sīrah only draw on Solomon during the middle section, the Wedding Quest section, and why does it make reference to only specific aspects of the Solomon legend, and in such an indirect way?

The answer to this is, I think, that the aspects of the Solomon legend that the sīrah is referencing here through the “new” stories it tells perfectly encapsulate the exploration of the themes of order and chaos that is being undertaken in the sīrah. Although it is a popular work of entertainment that relates Sayf’s personal heroic journey, at its core lies a discussion of kingship and the ability to rule. The first section of the sīrah, the Qamariyyah section, addresses the personal passage of Sayf from infant to king, his struggle to wrest his throne from the illegitimate and disastrous rule of his mother, and the beginning of a new, Islamic social order. The Wedding Quest section then describes Sayf’s eventually successful struggle for the wisdom and experience to control the forces that his ascent to the throne has set in motion, and the development of his social group into the beginnings of a stable, settled nation. In the final section, Sayf channels potentially destructive, aggressive, chaotic forces and externalizes them, unleashing his Muslim army onto the outside world, and bringing it into his new, Islamic order. The sīrah is fundamentally a tripartite discussion of the forces that govern society and how to control and manipulate them, and it does this to a great extent through using narrative episodes that address this through gender, in which (in the worldview of the sīrah) the forces of patriarchal, potentially stifling and stagnating, order are balanced against the forces of female innovative chaos and change.34 These forces are both necessary elements of society, but must be balanced so as to avoid either stagnation on the one hand, or a descent into anarchy on the other.

The underlying issue addressed in the Wedding Quest section of Sīrat Sayf in which the Solomon references occur is thus Sayf’s gradual realization of the necessary qualities of a good leader and his growing ability to recognize and manipulate the forces of order and chaos to achieve a balance essential for peace and stability. In its use of the Solomon intertext to inform this subtext, Sirat Sayf chooses its points of reference very carefully. The story of Solomon and Bilqīs, on one level— the Islamic stereotype of the perfect royal couple—is one that can be read as exploring the optimum balance of the forces of (male) order and (female) chaos through gender.35 This goes some way towards explaining why Solomon and Bilqīs are presented in Sīrat Sayf as husband and wife—the power struggle in their personal, marital relationship reflects the wider issue of societal power dynamics addressed in this section of the sīrah. This is a theme that is also explored through stories about Sayf’s own problematic marriages, with which the Solomon/Bilqīs intertext also resonates. Likewise, the characterization of the terrifying and threatening jinn al-Rahaṭ al-Aswad, coupled with his association with the figures of Solomon and Bilqīs, creates parallels between al-Rahaṭ and Ṣakhr, both of whom threaten to bring chaos and undermine the social fabric.

The Solomon-Bilqīs intertext is, therefore, being used to reflect general themes that are explored in the text. The section begins by introducing the frame story of the betrothal of ʿĀqiṣah and ʿAyrūḍ, which kicks off Sayf’s quest to Solomon’s Treasury. It reaches its plot climax in the subsection describing how the Muslims establish a settled society in Egypt and divert the Nile, and culminates in the marriage of ʿĀqiṣah and ʿAyrūḍ. The frame story of ʿĀqiṣah and ʿAyrūḍ’s betrothal and marriage, which rests on the Solomon/Bilqīs intertext, can be seen to have a fundamentally cosmic significance as a metaphor for the tensions within the Muslim social group.

The Solomon intertext in the Wedding Quest frame story

The Solomon intertext is first introduced at the very beginning of the Wedding Quest section via the dowry quest for Bilqīs’s crown and wedding robes, heroic heirlooms which themselves are symbols that encapsulate the basic elements of the gender and power struggle of the legendary romance. The crown, like the throne that plays such a symbolic role in the Solomon legend, is an obvious symbol of power and sovereignty. Sīrat Sayf’s use of the motif of Bilqīs’s wedding robes can clearly be read as symbolizing the maintenance of the natural order through the institution of marriage, given its connection with the figure of the Queen of Sheba who, as Lassner points out, has “two unnatural failings: she spurns the natural state of marriage and obeisance to man.”36 In addition to the connotations of the heirlooms themselves, their introduction into the text as objects of a dowry quest brings to the text of Sayf immediate echoes of the riddles set to Solomon by the Queen of Sheba, another kind of marital test.

Coincidentally, ʿĀqiṣah’s demand for these objects also marks the point of the sīrah at which her persona undergoes a sudden and drastic change. Throughout the Qamariyyah section, she plays the role of Sayf’s protective and loyal supernatural helper, but from this point onwards, like the Queen of Sheba, she takes on chaotic and dangerous characteristics which must be neutralized through marriage in order to prevent the destruction of the natural order.37 The significance of the motifs of the crown and wedding dress is thus two-dimensional. On the one hand, the presence of two such symbols of male power and female subjugation to the patriarchy draws on the theme of the beneficial union of order and chaos. However, the fact that these symbols are connected primarily with the figures of Bilqīs and ʿĀqiṣah (for whom the crown and gown are a precondition of marriage), both powerful, potentially chaotic figures in their own right, speaks to the related theme of the potential danger of unchecked female power, the actualization of which is a threat to the fabric of the patriarchal universe of the sīrah. The juxtaposition of these two themes informs the audience that this marriage will only be achieved with great difficulty.

Thus, the device of ʿĀqiṣah’s dowry demand at the beginning of the Wedding Quest section does not just introduce the motifs of Bilqīs’s crown and wedding robes, but also acts as a plot facilitator: it launches Sayf on a quest to save ʿAyrūḍ, and so provides a rationale for the action itself. In addition, by creating intertextual associations between Bilqīs and ʿĀqiṣah, it helps to establish a new set of audience expectations of ʿĀqiṣah’s behavior and character, and also of the subtextual theme of this second section of the sīrah, Sayf’s struggle to achieve a metaphorical marriage of order and chaos. It hints at the action to come, indicating that ʿĀqiṣah, like Bilqīs, must be incorporated into the natural order, and that this will be done through her marriage to ʿAyrūḍ.

Having said that, it is clear that the use of the Bilqīs intertext to inform the relationship between ʿAyrūḍ and ʿĀqiṣah is not simply an end in itself, but rather the means by which Sayf’s struggle to achieve a metaphorical marriage of order and chaos is highlighted. Throughout this section, ʿAyrūḍ appears as little more than Sayf’s creature or alter ego, often seeming to be simply a pawn in the conflict between Sayf and ʿĀqiṣah. This creates an ambience in which Sayf, in the guise of helper or companion, is perceived as the dominant male character. The spurned lover’s quest to the treasury is first and foremost a plot device that facilitates Sayf’s own journey and, as such, is given the bare minimum of narrative attention.38 Instead, we follow Sayf on his journey to the treasury and, when he finally arrives, he discovers that his need of the dress and crown, rather than ʿAyrūḍ’s, has been anticipated and that the queen has actually left instructions with the treasury’s guardians to help him retrieve them. (The device by which Sayf gains entry to the treasury, the recitation of his lineage, serves to further identify him rather than ʿAyrūḍ with the quest, as does Bilqīs’s reference to the fact that Sayf will arrive at Solomon’s Treasury “girded with swords” in her conversation with the treasury’s guardian, which brings the sword of Āṣaf back into intertextual play.39)

This association of Sayf rather than ʿAyrūḍ with the Solomonic subtext is strengthened as the section continues. Soon after the wedding robes and crown have been retrieved from the treasury, they are stolen from ʿAyrūḍ by another jinn, only to be found again by Sayf later on in the section, during an episode in which he is held captive by the nefarious and hideously ugly al-Thurayyā al-Zurqāʾ who has fallen in love with him. Furthermore, it is at this point, almost simultaneously to ʿAyrūḍ’s loss of the wedding robes, that Sayf loses Āṣaf’s sword when ʿĀqiṣah, furious with him for his support of her unwanted suitor, steals it from him in a fit of pique and flings it into the sea. This episode creates intertextual links between Sayf’s loss of the sword and Solomon’s loss of his ring of power, which was cast into the waters by another jinn, al-Ṣakhr (and, as noted above, at this point in the sīrah, ʿĀqiṣah has taken on chaotic, threatening aspects to her character which echo those of al-Ṣakhr in the Solomon legend).40 The Solomon intertext is more explicitly drawn upon when the sword later turns up in the hands of a jinn who is patiently awaiting Sayf, perched on a large stone column planted in the middle of the sea, provided by Āṣaf in anticipation of Sayf’s future hour of need:

On the eighth day [of drifting in his boat, lost in the sea, Sayf] saw a tall pillar of stone in front of him, rising from the shore, and on top of it was a tall tower which emanated a dazzling light. Sayf’s boat was drawn towards it, by God’s will, and when he drew near to it there was someone sitting at the top of the pillar, calling out, “Welcome, King Sayf b. Dhī Yazan.” With that, King Sayf turned towards him and shouted to him, “How do you know me?”

“O King, I have never met you before, but I have a rendezvous with you, and you with me, settled a long time since,” came the reply.

“How can that be?” Sayf asked. The stranger replied, “The reason is a strange and happy one. Āṣaf b. Barakhyā, the vizier of Lord Solomon, had made a sword of Yemeni steel and enchanted it against the jinn, and inscribed it with talismanic charms and proofs. He knew that it was destined, after a long time, to be possessed by a man called Sayf b. Dhī Yazan of tubbaʿī descent, and this person is you, O King of the Age. When he discovered this, he created the sword in your name, and God’s prophet Solomon said to him, ‘I know that it is inevitable that the sword will fall in the sea because of enmity and strife.’ And after he realized this, he ordered the jinn to bring this pillar from Jabal Marmar41… [and when it was built Solomon instructed me to wait on this pillar, and commanded my brother to bring me the sword when it was cast into the sea], then instructed me, ‘When you see a man approaching this place, travelling in a wooden boat filled with fruit, know that this is the predicted king, so greet him kindly and tell him that he is surely the rightful owner of the sword…’”42

Despite the fulfilment of ʿĀqiṣah’s dowry demand early on in the Wedding Quest section, she remains stubbornly opposed to marrying ʿAyrūḍ in the face of all efforts to persuade her. Their troubled courtship takes a back seat for most of the Wedding Quest section, but is brought back into the forefront in its final stages, after the Nile has successfully been diverted. Even though Sayf breaks the talisman that controls ʿAyrūḍ and crowns him as a king, ʿĀqiṣah continues to resist the marriage. She sets her betrothed several more trials designed to bring him to a premature end in an attempt to extricate herself from the situation. Eventually, she demands that he defeat a mighty mārid, called al-Samīdhaʿ, in single combat. When al-Samīdhaʿ (who has by now met ʿĀqiṣah and fallen in love with her himself, much like al-Rahaṭ before him) enters the battlefield and sees how comparatively puny and pathetic his opponent is, he laughs in ʿAyrūḍ’s face. But, against all the odds, ʿAyrūḍ prevails and ʿĀqiṣah undergoes an abrupt change of heart and now refuses to marry anyone but him.

Al-Samīdhaʿ is, we are told, one of two fearsome jinn who were imprisoned by Solomon within pillars of stone in Bilqīs’s palaces (the other one being al-Rahaṭ, who, in a repetition of his doomed love for Bilqīs, fell in love with ʿĀqiṣah earlier on in Sīrat Sayf, with a similarly hopeless outcome). Al-Samīdhaʿ can be read as a multiplication of al-Rahaṭ, like whom he embodies the destructive aspect of chaos.43 His defeat by ʿAyrūḍ mirrors his previous subjugation by Solomon, who had literally imprisoned him in the fabric of which his society was built. In Sīrat Sayf, the defeat of al-Samīdhaʿ facilitates the marriage of ʿĀqiṣah, likewise symbolic of the incorporation and subjugation of the forces of innovative chaos.

ʿAyrūḍ and ʿĀqiṣah’s eventual marriage marks the end of the Wedding Quest section, and the beginning of the final section of the narrative, the Hunt for Saqardīs and Saqardiyūn, in the course of which the entire world is incorporated into Sayf’s Islamic empire. From this point onwards, the Solomon-Bilqīs intertext, which reflects and informs both the characterization of Sayf and the main themes of Sīrat Sayf’s middle section, disappears from the story, as does the character of ʿĀqiṣah. The diversion of the Nile is one of the major plot points of the sīrah, and signals the final achievement of a unified social unit by the hero. This is undoubtedly why ʿAyrūḍ and ʿĀqiṣah’s marriage does not take place earlier: it is not until this is achieved that their symbolically loaded marriage can take place.

The Solomon intertext and the story of the enchanted fish

As in the case of the Treasury Quest frame story, the story of the enchanted fish and the imprisonment of al-Rahaṭ told by ʿĀqilah clearly refers to the same gender-based discussion of order and chaos that is being explored in the Solomon legend. Again, there are a number of direct equivalences between the events of Solomon’s time, as outlined by ʿĀqilah in the story, and this part of Sayf. Not only is the premise for al-Rahaṭ’s enslavement the same, the diversion of water, but the mārid falls in love with ʿĀqiṣah as he previously did with Bilqīs. Just as in ʿĀqilah’s story Solomon is faced with a series of increasingly impudent demands made by Bilqīs, Sayf is subjected to a list of marital demands made by his jinn foster sister. In both cases, the king is forced to walk a tightrope between appeasing and incorporating the forces of chaos, and unleashing them in their most destructive aspect: Bilqīs and ʿĀqiṣah must be appeased and the threatening, chaotic jinns Ṣakhr, al-Rahaṭ, and al-Samīdhaʿ must be bested. Both the significance of this and the general narrative tension in Sīrat Sayf are heightened by the repeated intertextual reminders, through the persona of al-Rahaṭ, and after him al-Samīdhaʿ, of the story told by ʿĀqilah of the brass fish in which Solomon must risk incurring the wrath of God in order to please his wife.

In addition to reiterating the themes of appearance versus reality and the quest for wisdom, the repetition of the fish story at this point in the text brings a sense of continuity and internal intertextual association into Sīrat Sayf.44 The point at which ʿĀqilah tells Sayf the second story of the brass fish and al-Rahaṭ occurs when the narrative is returning to focus on Sayf himself, having been interrupted by the adventures of his sons, which have a different thematic agenda. The inclusion of the story of the fish at this point is an internal intertextual reference to Sayf’s quest to Solomon’s treasury at the very beginning of the section, as well as to the fish story told to him by Shaybūb while he rested near the enchanted pool. It functions as a device through which the audience is reminded of all the themes that the Bilqīs intertext has previously been used to highlight, allowing the narrator to quickly re-establish his subtextual thematic base.

It would appear that the story of the enchanted fish is one that is integral to other recensions of Sīrat Sayf. In a recent study of female characters in manuscript versions of Sīrat Sayf, Zuzana Gažáková describes a slightly different version, which occurs right at the beginning of her primary manuscript, MS 4592, Cairo, Dār al-Kutub:

Commentaries related to gender discourse appear as soon as the sīrah starts, with a short narration about Queen Bilqīs and King Sulaymān which is loosely incorporated into its opening. When Bilqīs asks Sulaymān to build a castle of remarkable beauty for her, he complains that: “This is a typical women’s feature—to ask men to perform tasks they are unable to fulfil and then to tell each other that a man is able to do everything” (hādha min ǧumlat ṭabāyiʿ an-nisāʾ annahum yaṭlubū min ar-riǧāl mā yaʿǧizū ʿanhu wa yaqulna li baʿḍihinna inna ‘r-raǧul ʿala kull shayʾ qadīr). After that, Sulaymān openly says that he will fulfil her wish if she grants him sexual intercourse. Bilqīs agrees to this, and he engages in the construction of a castle with an enchanted lake inside full of golden fish. In order to make them come alive, both of them are requested to be sincere with each other. Bilqīs insists that Sulaymān take the first turn, and she emphasizes his masculine power and authority; this was apparently the right moment for the storyteller to stimulate the largely male audience: “You are superior. Men are truly superior to women in all aspects and situations” (anta mutaqaddim faʾinna ‘r-riǧāl mutaqaddimūn ʿala ‘n-nisāʾ fī sāʾir al-umūr wa ‘l-ḥālāt). The story finishes with the mutual recognition that if they could each enjoy younger partners, they would prefer them instead of each other’s company.45

This is intriguing, not just because it is interesting to find this particular story told in other Sayf texts, but because it is used in a very different place in the text and seems to have some significant differences to the story as told in Sayf. The major themes of a sīrah are laid out in its introductory pages, so the inclusion of this story right at the beginning of MS 4592 gives a good indication that the Solomon/Bilqīs intertext plays an important role in at least one other variant of Sayf. There are also clear similarities in the way that both stories use sex and humor to explore issues of gender and power, which seems to indicate that the intertext is being used in the same way. However, the characterization of Solomon’s somewhat dismissive attitude to his wife, and Bilqīs’s apparently willing self-subordination to the patriarchy, seem to indicate a fundamental difference in how the manuscript story conceptualizes and thematically uses gender-related power structures.

Sīrat Sayf and the Kǝbrä Nägäst

Further to the thematic use of gender to discuss issues relating to kingship and social order discussed above, there may well be another reason that the Bilqīs intertext plays such a significant role, and this reflects the dialogic nature of the text. As has been mentioned by Bridget Connelly, the sīrah genre is fundamentally concerned with the anxieties of the social unit and that unit’s struggle to maintain its integrity.46 The text primarily functions as a forum for discussing this, in which different, often conflicting, voices are able to coexist. It is evident that Sīrat Sayf references the Solomon intertext in a very specific way, through the figure of Bilqīs, the Queen of Sheba, who is consistently presented in the context of her marriage to Solomon. The stories recounted about her all figure her as Solomon’s wife, and Sayf’s quest to Solomon’s Treasury, in which she has left her wedding robes and crown for him as heroic heirlooms, looms large in the narrative and provides the framework for the entire second section. The Islamic Solomon intertext serves partly as a device through which to discuss Sayf’s fitness to rule, his Solomonic qualities, but there is a tension in the identification of Sayf as a descendent of both Solomon and Bilqīs. Throughout the sīrah, Sayf is described in terms of his patrilineal ancestry: his identity is defined by his being his father’s son; he frequently recites his lineage, which follows his forefathers back through the male line to Shem, Noah’s son; and all his heroic heirlooms are inherited from male donor figures. Against this background, the link that the text creates between Sayf and Bilqīs by presenting him as de facto heir to her treasury runs against the grain. It may be no coincidence that the Kǝbrä Nägäst, the Ethiopian national epic, relates the story of the descent of the Ethiopian kings from a son born to Solomon and the Queen of Sheba.

The Kǝbrä Nägäst opens with very brief introductory outlines of the history of the early prophets and the creation of the Ark of the Covenant. These are followed by a lengthy account of the story of King Solomon’s building of the Temple of Jerusalem and the Queen of Sheba’s visit, during which Solomon conceives a child with her.47 During her return journey to Ethiopia, the queen gives birth to a son, Menelik.48 As the boy grows up, he begins to ask about his father, and when he reaches the age of twenty-two, the queen sends him to Jerusalem to visit Solomon. Solomon wants to appoint Menelik as his heir, but Menelik wishes to return to his mother’s country. Eventually, Solomon relents, and sends him back to Ethiopia after anointing him as King of Ethiopia, accompanied by the firstborn sons of his nobles. However, Menelik’s companions are loath to leave without the Ark and hatch a plan to steal it. The plan is clearly met with divine approval as the Angel of God assists them in their venture. When Solomon discovers this outrage, he sets off in hot pursuit, but eventually realizes that the Ark has been lost to him through God’s will. He laments bitterly, but is consoled by the Spirit of Prophecy, and returns to Jerusalem at peace with the knowledge that the Ark has passed to his firstborn son. Menelik returns to Ethiopia as an anointed king, bearing with him the Ark of the Covenant, and founds a dynasty, in what has, coincidentally, also been described as a “reverse exodus.”49

The Kǝbrä Nägäst is another story of the foundation of a divinely-sanctioned dynasty bringing the light of true faith into the world which, like Sīrat Sayf, seems to have reached recognizable form as a national epic sometime between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries (although it is thought to have been in circulation possibly as early as the first century AD in some form, and there were certainly Coptic versions of related stories in circulation in the seventh century). The Ethiopian Queen of Sheba has received very little literary attention,50 but several scholars have commented on the clear relationship between the opening of the Kǝbrä Nägäst and a Coptic Egyptian version of the story of Bilqīs’s visit to Solomon written in Arabic.51 According to Fabrizio Pennacchietti, the African and later Latin Christian accounts of the encounter between Solomon and the Queen of Sheba differ substantially from the Jewish and Muslim narratives in that they dispense with two elements of the story: the role of the jinn in helping Solomon to build the Temple and the riddles that characterize the Islamic accounts of the meeting of Solomon and the queen. Instead, the story “is firmly grafted on to what may be called the pearl of Christian tales, the so-called ‘Legend of the wood of the Cross.’”52

In the Coptic account summarized by Pennacchietti, Solomon needs to acquire a strong tool to cut the blocks of stone needed to build the Temple. He orders the capture of a rukh chick, “a fabulous bird of enormous size,” which is placed under an upturned copper cauldron in the courtyard of his palace. The rukh’s mother, determined to free him, brings a tree trunk from the Garden of Eden, and drops it onto the cauldron, which breaks. The rukhs escape, and Solomon uses the tree trunk to break up the stones for the Temple—when they are touched by the trunk, they simply break into the required size. Meanwhile, Solomon is told that the Queen of Sheba has arrived in the city to visit him, and that she has a “monstrous leg like the hoof of a goat.” He orders the esplanade of the Temple flooded, so that the queen will have to raise her skirts when she walks across it to his throne. However, as she wades through the water, her leg is touched by the tree trunk, which happens to be floating past, and is immediately transformed into a perfect human leg. The tree trunk is later placed in the Temple and adorned with silver, which is, in later times, used to produce the thirty pieces of silver paid to Judas for his betrayal of Jesus, while the cross of Christ is carved from the tree trunk.

Although the Coptic legend ends here, the Kǝbrä Nägäst continues the story, recounting how, when the Queen of Sheba decided to return to her own lands, Solomon (who has four hundred queens and six hundred concubines) resorts to trickery to bed her before she leaves. He gives a feast in her honor at which “with wise intent Solomon sent to her meats which would make her thirsty, and drinks that were mingled with vinegar, and fish and dishes made with pepper.”53 Once the feast is over, and everyone else has left, he persuades her to stay the night there with him. The queen asks him to swear that he will not take her by force if she does so, and Solomon gives her his word, as long as she gives him her word that she will not “take by force anything that is in my house.”54 He orders a servant to leave a bowl of water in the room and when, extremely thirsty during the night, the queen goes to drink it, he tells her she has broken her oath, thereby freeing him from his, and refuses to let her drink unless she agrees to let him have his way with her. As they sleep later, Solomon has a portentous dream, and gives the queen one of his rings, to remember him by and as a token of recognition in case she bears him a son.

The Coptic and Kǝbrä Nägäst accounts do thus, arguably, retain the basic tropes of magical or miraculous building found in the qiṣaṣ versions of the Solomon legend (the jinn are replaced by the miraculous tree trunk in the Coptic account, but this is not included in the Kǝbrä Nägäst), and of trickery (the riddles which lead to the queen’s submission to Solomon are replaced by the seduction by trickery), but they are very different stories. However, the way that the Solomon pretext is referenced in Sīrat Sayf seems to indicate that the Kǝbrä Nägäst, or Kǝbrä Nägäst-type stories, of the Queen of Sheba are incorporated into its intertextual pantheon. This suggestion is based on two things: the fact that the references in Sīrat Sayf are to a postmarital relationship of Solomon and Bilqīs, and the fact that the sīrah establishes a relationship between Sayf and Bilqīs, as well as Sayf and Solomon.

The fact that the major tendency in Sīrat Sayf is to refer to Solomon legends in the context of a post-marital relationship with Bilqīs, rather than through the premarital wisdom-test encounter of Solomon and Bilqīs as found in the qiṣaṣ, is intriguing. The major theme of qurʾānic references to the Solomon legend is the battle of wits between the prophet and the non-believer, and the demonstration of the superior, God-given knowledge of Solomon in comparison to Bilqīs who, however intelligent and erudite she may be, and however capable a queen to her people, cannot hope to win out against him. Bilqīs’s part in the qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ likewise focuses on this encounter, and she disappears from the legend with Solomon’s victory. However, what we see in Sīrat Sayf is that, although the theme of the test of wits is maintained in the stories it tells about Solomon and Bilqīs, she appears exclusively as Solomon’s wife following the encounter that is the focus of her role in the Qurʾān and qiṣaṣ. There is a clear difference between the Queen of Sheba’s role in Sīrat Sayf and in the Kǝbrä Nägäst, in that Solomon and Bilqīs are by no means man and wife in the Ethiopian account (this is made very clear by the fact that the queen is seduced against her will, by unscrupulous trickery). However, Sīrat Sayf’s reliance on a characterization of Solomon and Bilqīs as man and wife who leave an inheritance to Sayf has correspondences to their roles in the Kǝbrä Nägäst, in which, although not married, their primary narrative function is as parents of Menelik, the founder of a dynasty of kings and the bringer of the true religion to Ethiopia.

There is also a shift of emphasis away from Solomon and onto Bilqīs in the intertextual references Sīrat Sayf makes to Solomonic legend that is characteristic of the Ethiopian story.55 It is from Bilqīs that Sayf inherits the crown and wedding robes needed to fulfill ʿĀqiṣah’s dowry quest, and it is because of al-Rahaṭ’s love for Bilqīs that he ends up imprisoned by Solomon, conveniently trapped and waiting for Sayf to liberate him to help divert the Nile. One might expect Sayf to have inherited Solomon’s ring or throne, for example, given that these are motifs that are inextricably associated with Solomon in Islamic legend, rather than Bilqīs’s robes and crown and Āṣaf’s sword. However, the focus in Sayf on Bilqīs as the wife who must be appeased in the stories of the enchanted fish is striking because she is so clearly portrayed as the partner with more power in their marriage. Thus Sayf, through his connection with Bilqīs in the Wedding Quest section, in which he is the heir to whom Bilqīs leaves her talismanic treasures, might very well be identified with the Ethiopian Queen of Sheba’s son Menelik by those who know the Kǝbrä Nägäst and associated stories.

This potential identification of Sayf with Menelik is intriguing because Menelik can be seen as reflecting Ethiopian notions of sacred kingship in much the same way as I have identified Sayf’s persona as embodying ancient Egyptian ideas of kingship elsewhere.56 This identification brings another dimension to Sayf’s characterization, which in turn informs the discussion of kingship that is a core concern of the sīrah. Furthermore, it adds an interesting nuance to the issue of Sayf’s literary legitimacy as king and founder of his dynasty, given that by the end of the sīrah Sayf becomes the ruler of Ḥabash, the major enemy of the Egyptian Yemenites, who are defeated and incorporated into Sayf’s empire in the final stages of the narrative. In terms of the story that Sīrat Sayf is telling, the text can be read as creating a tension between the legitimacy of Sayf Arʿad’s claim to the Ḥabashī throne and Sayf’s. This is because, if Sayf can be identified with Menelik, when he defeats the Ḥabashī king Sayf Arʿad and takes his throne he is, in one sense, claiming his legitimate birthright.57

This aspect of Sayf’s characterization can also be read into his parentage: Sayf is always described as his father’s son, but his mother, Qamariyyah, is an African concubine who was sent to Dhū Yazan as a gift from Sayf Arʿad.58 Identity is very much informed by parentage in popular epics, and Sayf’s mother brings an “African” dimension to his persona. Although he is always identified in the text as a Yemenite descendent of the Ḥimyarite kings, he is actually a descendent of both Ham and Shem, half African and half Arab.59 Despite the fact that there is an obvious tension between Sayf as Islamic progenitor and Menelik as a Christian one, the identification between these two at the level of their shared characterization as founding rulers who bring the light of the true faith to the world is one that is cross-cultural. It can be read as reflecting the essentially inclusive worldview of Sīrat Sayf, and the underlying idea of the brotherhood of man which is a key theme of the text.

In terms of intertextual consistency, the preeminent role of the Ethiopian Queen of Sheba in the Kǝbrä Nägäst also ties in neatly with the focus on the figure of Bilqīs in Middle Eastern, and specifically Yemeni and Egyptian, premodern popular histories and literature, in which figures such as Bilqīs and Zenobia can be read as vehicles through which issues of social order and chaos are discussed. Given the significance of the Queen of Sheba in terms of Ethiopian culture and literature, as well as Yemeni tradition, not to mention the nature of the heirlooms involved, it does not seem farfetched to read into this the intertextual existence of a broader level of dialogue on social and cultural frictions and assimilation which works at a more regional level, encompassing South Arabia, Ḥabash, and Egypt.60 Although these three geographic areas have long been separate political entities, they have a history of trade and cultural links.61 What is more, the fluctuating borders of Ḥabash have incorporated large swathes of South Arabia and Egypt at various times. In fact, Sīrat Sayf is rooted in the historical actuality of territorial conflicts between Ḥabash and Ḥimyar in the Arabian Peninsula, as well reflecting the later, medieval tensions between Egypt and Ḥabash.62

Conclusion

To conclude, the references Sīrat Sayf makes to the Solomon legend are nuanced and complex. It is easy to say that Sayf and Solomon have basic characteristics in common, and these undoubtedly do explain the presence of references to Solomon in the sīrah. The Wedding Quest section of Sīrat Sayf is especially concerned with the control of the jinn, the building of palaces and cities, and the diversion of the river Nile. Given Solomon’s unique status in Islamic popular culture as the ultimate prophet-king, and the popularity of stories about him, it might seem unremarkable that he would be an intertextual presence in a sīrah about another Islamic world-king, and the implicit identification of the two characters is certainly a narrative device that is employed to enhance Sayf’s heroic status. It builds on the oft-repeated predictions of Sayf’s destiny as world ruler made in the text, paving the way for the climactic third section in which the Muslims embark on an inexorable march throughout any still unconquered earthly lands and into the realms of the jinn.

However, the sīrah goes far beyond just bringing in heroic heirlooms and Solomonic motifs to inform Sayf’s characterization. It manipulates the Solomon legend and plays with the audience’s assumed knowledge of the narrative to inform its own themes. It seems to create new Solomon stories for the ends of its own plot, and to generate narrative tensions. Perhaps most importantly, it seems to be using the Solomon legend as a dialogic device through which to speak to (and for) not just an Islamic, Egyptian audience, but also a Christian and Ethiopian one. (Without looking at more examples of specifically Egyptian Christian religious legends it is impossible to make any more concrete arguments on this aspect of the text’s intertextual dialogue, but it would be extremely surprising if the Egyptian Coptic intertext did not play a large role).

As Michael Jackson has recently commented, storytelling fulfils several functions. It is a way that we “recount and rework events that happened to us,” but we also tell stories to share experiences, to affirm our identity, and to transform our sense of who we are.63 Storytelling has a cathartic function that helps us to come to terms with and make sense of traumatic events, loss, and hardship. Communally authored narratives such as Sīrat Sayf do this by allowing space within themselves for multiple voices to exist, often voices with diametrically opposed views. These narratives are not univocal, but are dialogic discussions of issues such as cultural identity and are a way of airing and reconciling different truths. The identification of Sayf with both the Islamic Solomon and the Ethiopian Queen of Sheba informs his heroic character and the story of his own personal quest. However, it also makes him a more universal hero and opens up the narrative experience to a more diverse audience. It is one of many similar uses of intertextual references made in Sīrat Sayf that allow it to be a space in which issues surrounding identity and society can be explored and negotiated. At the same time, it works to convey one of the central themes of the sīrah, the role of Sayf b. Dhī Yazan as the world king who brings an inclusive message of Islamic unity to the worlds of humans and jinn.

About the author

Helen Blatherwick (SOAS, University of London) is interested in premodern popular and classical Arabic literature and Qurʾānic Studies. She is the author of Prophets, Gods and Kings in Sīrat Sayf ibn Dhī Yazan: An Intertextual Reading of an Egyptian Popular Epic (Leiden: Brill, 2016), and co-editor with Shawkat Toorawa of a special issue of the Journal of Qur’anic Studies on “The Qur’an in World Literature” (2014).

Notes

1 This article is based on a paper presented at the conference “Islamic Stories of The Prophets: Semantics, Discourse, and Genre” held in Naples, October 14–15, 2015. I would like to thank the organizers, Marianna Klar, Michael Pregill, and Roberto Tottoli, for giving me the opportunity to present, and the Mizan Project and the Rector and Dipartimento Asia, Africa e Mediterraneo of the University of Naples L’Orientale for their generous funding and hospitality. This article is based in material from my recently published monograph, Prophets, Gods and Kings in Sīrat Sayf ibn Dhī Yazan: An Intertextual Reading of an Egyptian Popular Epic (Leiden: Brill, 2016), but this has been revised, refocused, and expanded, including the addition of material on Ethiopian Queen of Sheba stories. I would also like to thank Wendy Belcher and the anonymous reviewers for their comments on an earlier draft of this article.

2 Medieval Arabic writers often use the term Ḥabash loosely to refer to sub-Saharan Africa, but, strictly speaking, Ḥabash was the designation for a region situated in modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea. Its fluctuating borders sometimes incorporated parts of modern-day Egypt, and sometimes parts of the Arabian Peninsula (see E. Ullendorff, J.S. Trimingham, C.F. Beckingham, and W. Montgomery Watt, “Ḥabas̲h̲, Ḥabas̲h̲a” in Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.; Leiden: Brill, 1954–2005), s.v., and El Amin Abdel Karim Ahmed, “Habasha, Abyssinia and Ethiopia: Some Notes Concerning a Country’s Names and Images,” in University of Khartoum Annual Conference of Postgraduate Studies and Scientific Research: Humanities and Educational Studies February 2013, Conference Proceedings Volume One (Khartoum: n.p., 2013), 399–415). It is the latter designation that is clearly intended in Sīrat Sayf.

3 Aboubakr Chraïbi has argued, based on his reading of a sixteenth-century manuscript, that the story of Sayf’s journey into Egypt is informed by the Moses legend, hence he uses the term “reverse exodus.” See Aboubakr Chraïbi, “Le roman de Sayf ibn dî Yazan: sources, structure et argumentation,” Studia Islamica 84 (1996): 113–134. See also Blatherwick, Prophets, Gods and Kings, 110–116.

4 The sīrah genre is one in which narratives are inherently fluid, which means that there is no one definitive version of the text. The different extant manuscript variants adhere to a main plot and structure, and tend to maintain consistency in the initial stages of the story, but can diverge greatly in plot and detail within this overall framework, especially in the later stages of the narrative. The version of Sīrat Sayf discussed in this article is the widely available four-volume printed edition Sīrat al-malik Sayf ibn Dhī Yazan fāris al-Yaman (4 vols, Beirut: al-Maktabah al-Thaqāfiyyah, 1407 [1986]). This is a reprint of the Būlāq edition, first published in 1294 [1877].

5 See n. 35 and n. 37 below, and also Blatherwick, Prophets, Gods and Kings, 39–40, 44–49, and 51.

6 An interesting discussion on similar premises that explores the structural and thematic similarities between American stories of the outlaw Jesse James and the New Testament accounts of the life of Jesus can be found in Robert Paul Seesengood and Jennifer L. Koosed, “Crossing Outlaws: The Life and Times of Jesse James and Jesus of Nazareth,” in Roberta Sterman Sabbath (ed.), Sacred Tropes: Tanakh, New Testament, and Qur’an as Literature and Culture (Biblical Interpretation Series 98; Leiden: Brill, 2009), 361–371.

7 I use the term ‘pretext’ here rather than ‘hypotext’ as I am not positing a direct link between two specific texts, but a more general reliance on the intertextual nexus of legends and associations that surround figures such as the Islamic prophets.

8 See Sīrat Sayf, 1.9–10.

9 For the variant of the Ham story as told in Sīrat Sayf, see 1.49. Noah’s curse is more usually referred to as “the curse of Ham,” but the sīrah consistently refers to it as “Noah’s curse.” For more on the curse in Sīrat Sayf, see Blatherwick, Prophets, Gods and Kings, 81–87 and 251–253, and M. O. Klar, Interpreting al-Thaʿlabī’s Tales of the Prophets: Temptation, Responsibility and Loss (London: Routledge, 2009), 178 and 183–184. For the curse in the qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, see ibid., 151–155 and 171–176. And for the curse in general, see Roland Boer and Ibrahim Abraham, “Noah’s Nakedness: Islam, Race and the Fantasy of the Christian West” in Sabbath (ed.), Sacred Tropes, 461–473; David M. Goldenberg, The Curse of Ham: Race and Slavery in Early Judaism, Christianity and Islam (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003); and Gordon D. Newby, “The Drowned Son: Midrash and Midrash Making in the Qur’an and Tafsīr,” in W. M. Brinner and Stephen D. Ricks (eds.), Studies in Islamic and Judaic Traditions: Papers Presented at the Institute for Islamic-Judaic Studies (2 vols. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1986), 2.19–32.

10 “Narrative and iconographic conventions link nearly all the great heroes with some specific emblems of identity. One of the several types of emblem is the heirloom, a kind of heroic hand-me-down” (John Renard, Islam and the Heroic Image: Themes in Literature and the Visual Arts [Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1993], 141; see 140–145 for his discussion of such emblems).

11 See Sīrat Sayf, 1.225–234 and 2.256–269, respectively.

12 For example, “King Sayf b. Dhī Yazan drew the sword of Āṣaf b. Barakhyā, and said to the sorcerer al-Shāhiq, ‘Take this sword, kiss it, and place against the back of your neck (lit. ʿalā raʾsik). If your faith is sound it will cause you no pain and you will not be wounded, and what you have said [about your conversion to Islam] is true. But if it is otherwise, you will die’” (Sīrat Sayf, 3.131).

13 More detailed summaries of Sīrat Sayf can be found in Blatherwick, Prophets, Gods and Kings, 26–51, and Malcolm Lyons, The Arabian Epic (3 vols.; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 586–641. Rudi Paret has also provided a summary of the sīrah, along with historical background and comprehensive name and place indices (Rudi Paret, Sīrat Sayf ibn Dhī Jazan: Ein arabischer Volksroman [Hannover: Orient-Buchhandlung Heinz Lafaire, 1924]). This has recently been translated into English by Gisela Seidensticker-Brikay as Siirat Sayf ibn Dhi Yazan: an Arabic folk epic (Maiduguri: University of Maiduguri, 2006). The first section of the sīrah, the Qamariyyah section, has been translated by Lena Jayyusi as The Adventures of Sayf Ben Dhi Yazan, An Arab Folk Epic (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1996). For an overview of scholarship on Sīrat Sayf, see Blatherwick, Prophets, Gods and Kings, 4–6, and Zuzana Gažáková, “Remarks on Arab Scholarship in the Arabic Popular Sīra and the Sīrat Sayf Ibn Dī Yazan,” Asian and African Studies 14 (2005): 187–195.

14 “A frame story may be defined as a narrative whole composed of two distinct but connected parts: a story, or stories, told by a character or several characters in another story of lesser dimensions and subordinate interest, which thus encloses the former as a frame encloses a picture” (Mia Gerhardt, The Art of Storytelling: A Literary Study of the Thousand and One Nights [Leiden: Brill, 1963], 395. See 395–416 for her full discussion of frame stories).

15 Sīrat Sayf, 2.185–186.

16 For the story of the creation of these fish, see Sīrat Sayf, 2.405–408. The motif of Solomon building palaces for Bilqīs is a common one in Middle Eastern popular literature; see, for example, W. Montgomery Watt, “The Queen of Sheba in Islamic Tradition,” in James Pritchard (ed.), Solomon and Sheba (London: Phaidon, 1974), 85–103.

17 Sīrat Sayf, 2.405.

18 Sīrat Sayf, 2.411.

19 Ibid., 2.431.

20 The text has jabal qāf, which is normally translated as Mount Qāf. Jabal qāf can either refer to a single mountain, a range of mountains that encircle the world, or a range of mountains in the Caucasus (often associated with Gog and Magog). It is clear from the text that here it is conceived of as a range of mountains rather than a single peak, and it seems to be consistently used in Sīrat Sayf to refer to a mythical realm which is the home of the jinn. For more on the jabal qāf, see Daniel G. Prior, “Travels of Mount Qāf: From Legend to 42° 0’ N 79° 51’ E,” Oriente Moderno 89 (2009): 425–444.

21 It is possible to read two structures at work in Sīrat Sayf. The first is a linear structure, while the second is a loose ring structure with a central climax. See Blatherwick, Prophets, Gods and Kings, 25 and 52–53.

22 See Sīrat Sayf, 3.222. Several of these objects can be described as prophetic emblems of identification: the sword of Āṣaf, the emerald horse Barq al-Barūq al-Yāqūtī (the name of which calls to mind the Prophet Muḥammad’s horse, al-Burāq), the pick of Yāfith b. Nūḥ (Japheth), the talisman of Kūsh b. Kinʿān (who is one of the sons of Ham according to Islamic tradition), and al-Rahaṭ al-Aswad.

23 See below, n. 33.

24 Sīrat Sayf, 3.225.

25 Sīrat Sayf, 3.226.

26 Sīrat Sayf, 3.226.

27 A mārid is a particularly powerful and malevolent type of jinn.

28 Sīrat Sayf, 3.228–229.

29 The various accounts consulted here are:

(i) ʿUmārah b. Wathīmah’s Kitāb Badʾ al-khalq wa-qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, for which see: Raif Georges Khoury (ed.), Les légendes prophétiques dans l’Islam depuis le Ier jusqu’au IIIe siècle de l’Hégire. Kitāb bad’ al-ḫalq wa-qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ. Avec édition critique du texte, ed. R. G. Khoury (Codices Arabici Antiqui 3; Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1978), 102–180.

(ii) Al-Thaʿlabī’s ʿArāʾis al-majālis, for which see: Abū Isḥāq Aḥmad b. Muḥammad b. Ibrāhīm al-Thaʿlabī al-Nīsābūrī, Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ al-musammā ʿArāʾis al-majālis (Beirut: al-Maktabah al-Thaqāfiyyah, n.d.), 257–293. This is available in English translation, for which see ʿArāʾis al-majālis fī qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, or ‘Lives of the Prophets’ as Recounted by Abū Iṣḥāq Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad ibn Ibrāhīm al-Thaʿlabī, trans. William M. Brinner (Leiden: Brill, 2002), 482–548.

iii) Al-Kisāʿī’s Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, which is available in three printed editions (based on different manuscripts): (1) Vita Prophetarum auctore Muḥammed ben ʿAbdallāh al-Kisaʾi ex codicibus, qui in Monaco, Bonna, Lugd. Batav., Lipsia et Gothana asservantur, ed. Isaac Eisenberg (Leiden: Brill, 1923), 267–299; (2) Badʾ al-khalq wa-qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ li’l-Kisāʾī, ed. al-Ṭāhir b. Sālmah (Tunis: Dār Nuqūsh ʿArabiyyah, 1998), 336–360; and (3) Qiṣaṣ wa-mawālid al-anbiyāʾ, ed. Khālid Shibl (Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyyah, 2008), 279–304. Al-Kisāʿī’s collection is available in English translation, for which see The Tales of the Prophets of al-Kisāʾī, trans. Wheeler M. Thackston (Boston: Twayne, 1978), 288–320 (this is a translation of the Eisenberg edition).

iv) Ibn Kathīr’s Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, for which see: ʿImād al-Dīn Abū’l-Fiḍā Ibn Kathīr, Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, ed. ʿAlī ʿAbd al-Ḥamīd Abū’l-Khayr, Muḥammad Wahbī Sulaymān, and Maʿrūf Muṣtafā Zurayq (Beirut: Dār al-Khayr li’l-Ṭibāʿah wa’l-Nashr wa’l-Tawzīʿ, 1417 [1998]), 440–467.

v) ʿAlī b. al-Ḥasan Ibn ʿAsākir’s Tārīkh madīnat Dimashq, for which see: Tārīkh madīnat Dimashq, ed. ʿUmar b. Gharamah al-ʿAmrawī and ʿAlī Shīrī (80 vols.; Beirut: Dār al-Fikr, 1995–2001), 22.230–299.