PDF

Download

Citations

Click and drag then release to select a passage to cite.

Annotations

How to submit annotations to Mizan Journal articles:

your work is published.

Search within

Shahrazad

Shahrazad

On a previous occasion, I have argued that the Thousand and one nights, and especially the framing story, is related to the ancient genre of the mirror for princes, the tradition of wisdom literature developed particularly in Iran and the Middle East. This is suggested first by its form, a framing story containing a narrative intrigue, enclosing a series of embedded tales interacting with the frame in order to convey instructions to the king, the prince, and, of course, the reader. The example that comes to mind is the well-known cycle of the Seven viziers, whose origins go back to Sasanian sources, and which has been preserved in Arabic and Persian versions from the 10th-12th centuries.

The intrigue of the cycle is related to the motif of the ‘predator woman’ which can be found, for instance, in the story of Joseph and the wife of Potiphar, or Yusuf and Zulaykha, and is widespread in misogynistic texts in all pre-modern literary traditions. The story revolves around a young prince who may not speak for seven days – following a prediction – and is lodged in the women’s compound for that period. One of the concubines of the king attempts to seduce him into killing his father, usurping the throne, and marrying her. When the prince rejects the advances, she accuses him of having violated her. The king decides to execute the prince, but the viziers intervene. A trial ensues in which each of the viziers and the concubine in turn tell stories to support their case, until in the end, after seven days, the truth is discovered, and the concubine is punished.1

Rembrandt, Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife, etching, 1634 © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett.

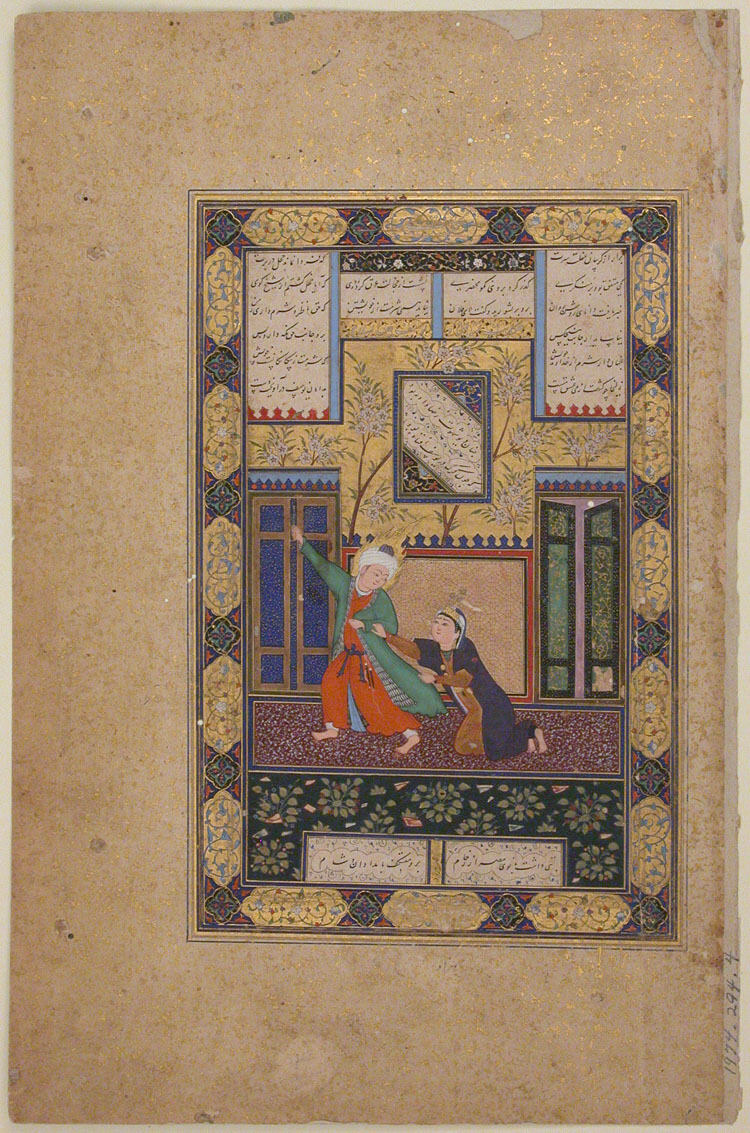

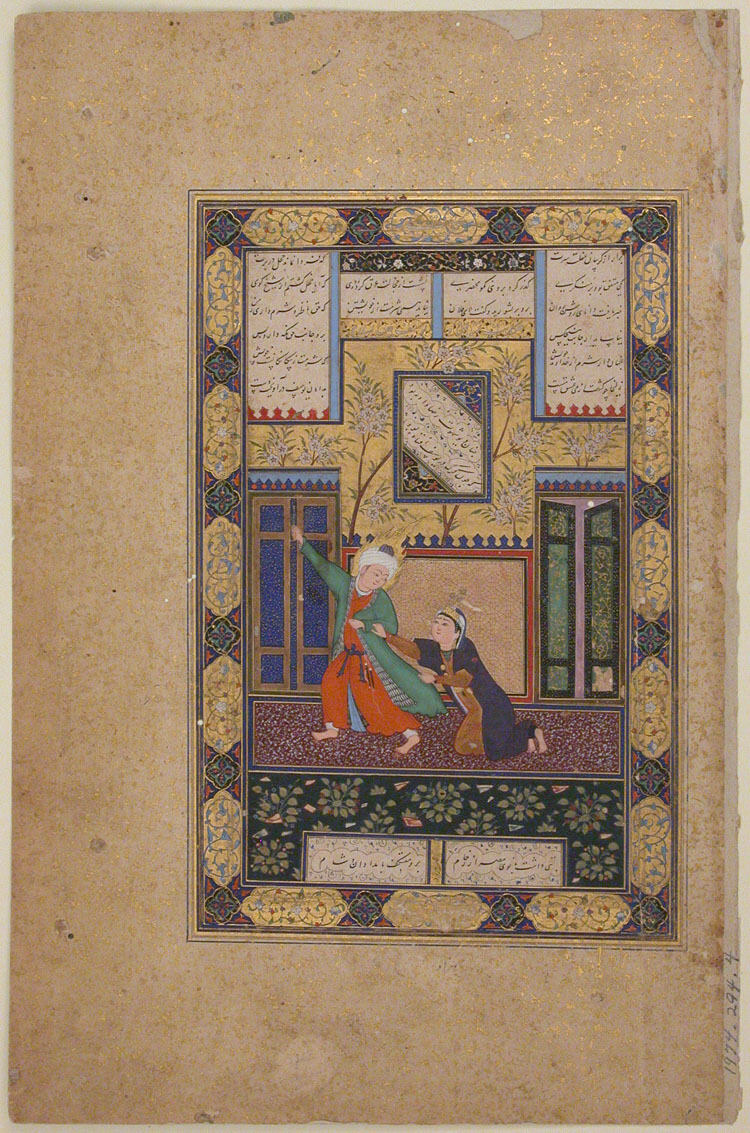

“Yusuf and Zulaikha,” Folio 51r from a Bustan of Sa`di ca. 1525–35. Image via the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This cycle, which is incorporated in some versions of the Thousand and one nights, as ‘The craft and malice of women’2 seems to expand first on the nature of kingship and power. Repeatedly the viziers summon, or even beg, the king not to react impulsively and rashly, and examine the case thoroughly before pronouncing a verdict. They refer especially to two foundations of just and proper rule: rationality and the reservoir of wisdom preserved in the tradition. In their tales they refer to both, to soothe the anger of the king and show him examples taken from real life of how to behave properly in this kind of situations. The key word is continuity: proper rule can only be secured when the dynasty and ancient customs can be preserved and transferred to the prince. It is in the prince where ultimately the components of authority, dynastic legitimacy and just government should converge.

The reproduction of these components, which represent the regular order of things, is threatened by a highly disruptive phenomenon: a woman. The concubine has all the time been safely confined to the women’s quarter, but through the temporary presence of the prince the traditional boundaries between the various courtly domains become porous, and immediately her feminine properties begin to challenge these boundaries and affect the functioning of the state. She mobilises all her feminine assets: she tries to seduce the prince; she pretends weakness vis-à-vis male violence; she plays on the king’s emotions by appearing before him weeping and wailing, with dishevelled hair and torn clothes, appealing to his empathy, pity, and sense of justice. There is no doubt about the nature of the confrontation taking place here: It is the collision between a stable tradition of good governance dominated by male rationality and equanimity, and an inherently disruptive realm of femininity, governed by lust, treachery, irrationality, emotions, and disloyalty.

Phyllis and Aristotle, 1530, by Lucas Cranach the Elder. Via Wikimedia Commons.

The cycle of the Seven viziers belongs to a misogynist tradition associated with what is often called ‘The wiles of women’, of which there are several examples on the corpus of the Thousand and one nights. These stores suggest that the nature of women is somehow incompatible with statecraft, which is, therefore, the privilege of men. They seem to oppose the very idea of governance to some quintessential notion of femininity. This opposition is not just an excuse to construct a narrative plot; it is a fundamental division of male and female domains, which is at the basis of the moral and political order. It presupposes a set of opposites and incompatibilities, such as physicality vs. wisdom, rationality vs. emotions, treachery vs. loyalty, lust vs. self-restraint, which structures the discourse of power.

Image via the Internet Archive.

If we look at our examples, we can observe several common elements, especially in the Sanskrit, Persian and Arabic cycles. First, the stories are typically connected with the succession to the throne, and thereby with the tension between interruption and continuity. The coming of age of a prince signals the moment when the throne, with the principles, traditions and discourses supporting it, should be handed down to the next generation, a moment in history when the dynasty is particularly vulnerable. Second, the cycles show a remarkable pre-occupation with the motif of silence vs. speech, as a state which excludes a person from the clamorous affairs of everyday life. The tension which silence, the absence of speech, engenders, as an enclave segregated from regular life, is solved by narration, that is, the telling of stories which connect the contending visions with the realm of the imagination and a specific illustrative form of discourse. Third, the cycles are constructed as frame stories, integrating various narrative levels which reveal the process of instructing the king or prince, thereby instructing the reader as well.

Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove, Japan, Edo period (1615-1868). Image via the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

One of the characteristics of the feminine stereotype is that action is based not on principles, but on emotions, desire, egoism, lust, and short-term profit. Because of the nature of the concubine’s interference, an appeal is made to the king directed not merely at his authority as a king, but more particularly to his position as a man, a father, and the master of the household. What the concubine attempts is to draw the process of succession out of the schedule of proper procedures and subject it to the diverse emotions and desires which are hidden underneath them. The king is unable to neglect this appeal. He cannot just dismiss the matter as a female whim, because it is his responsibility, inherent in his male role, to protect his women and to exert his authority as a father. In the end it is the viziers who succeed in re-incorporating the dilemma, and the process of succession, into the regular, formal, procedure.

The impulsive reaction of the king, therefore, is no anomaly, but is rather prescribed by his dual role. It does not render him unfit to perform his task as a king, but rather reveals that kingship is not confined to an official role only and presupposes a complex amalgamation of different roles. As a man and a father, the king must show his moral indignation at the incident and respond in an emotional way. But as a king, too, it is required of him to show an emotional response. After all, these emotions buttress his privilege to pronounce an arbitrary verdict in any given situation, and confirms that his position is ultimately based on his right, or prerogative, or even duty, in some occasions, to use violence. Therefore, the impulsive nature of the king’s response lays bare the fact that he is not merely imprisoned in an official status, but is a human being, too. His power is based on the elementary manifestations of human nature. The opposition of the two – feminine and masculine – manifestations is finally re-integrated into the formalized system of procedures, ancient customs, traditional wisdom, and the requirements of reason. Women are relegated to the margins where they are supposed to abide.

The discordant circumstances of the prince’s education reveal that kingship is not monolithic and does not consist of complete arbitrary rule vested in the person of the king. Of course, the king represents the legitimacy of his descent, and the privileges projected on him by tradition, resulting in his position of power. However, kingship is a complex role consisting of various components, including not only the person of the king, and its connotations, but also the principles and conventions of tradition, represented by the viziers. These components interact in a dialogic relationship, the king imposing the power which he derives from his person and privileges, the viziers harmonizing these necessary features with the more durable contexts of tradition, reason and wisdom. It is these two components which in the end not only secure the transition from one king to the next, but which also, and perhaps more importantly, allow the transformation of power, as a necessary element of kingship, into authority, a manifestation which is not merely based on the exertion of power, but rather on the ideologically and socially accepted form of rule as it has accumulated in history, within the frameworks of morality, religion, collective memory and social harmony.

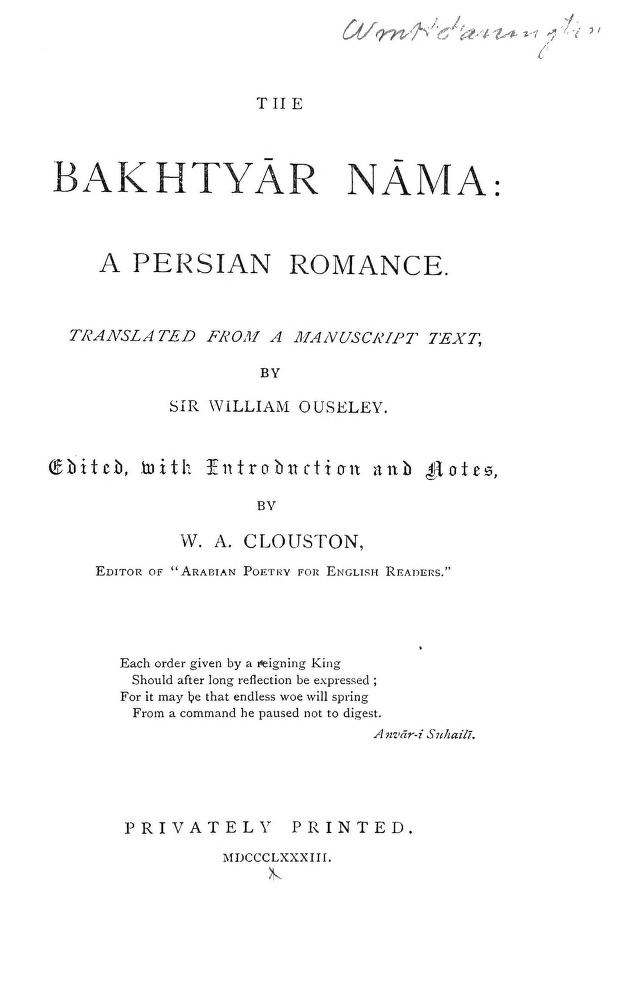

Image via HathiTrust.

In this construction of authority there is no role reserved for women. However, this is mainly an optical illusion, as the story itself seems to demonstrate. Like a building which is meant to keep specific enemies outside incorporates the idea of the existence and nature of these enemies in its design, concept and construction, the stronghold of kingship, designed to ward off feminine intervention, is fundamentally permeated with the female element. Because the stronghold is designed to keep the enemy out, the enemy is already inside. Although the women are enclosed in the women’s quarters, their segregation emphasizes their presence as an essential component, and their exclusion permanently implies the possibility of their – destructive – interference. A system which is constructed to exclude them, can inevitably survive only if their presence is continued. It is this paradox which is the main logic in the misogynist worldview conveyed in this type of narratives.

The feminine paradox, as described above, is not only conveyed by this type of literature in a concise form; it also represents the origins from which these narratives derive. After all, the intervention of the concubine generates the conflict and the phase of liminality in which all aspects of the kingship tradition and its antitheses are mobilized to restore order and secure the continuity of the state. It is the intervention of the concubine which brings to the surface the dialogic process on which authority is based, thereby fragmenting monologic, male, discourses of power. The concubine is the catalyst engendering a process of reconstitution of the dynasty, of the handing over of its traditional conventions, precisely by enforcing a rupture and threatening to discontinue it through regicide, patricide, and usurpation. As a result, the intervention allows for the display of the foundations of kingship which is ultimately meant for the education of the prince and, of course, the reader. It is no coincidence that this dialogic process is shaped as an exchange of tales: in the end it is narration which realizes the reconciliation between human nature and the eternal, socially accepted, principle of authority.

Within the perspective of the masculine vision of power and authority, on the one hand the marginalization and isolation of the feminine element is legitimized by the women’s alleged destructive and irrational influence. However, on the other hand, women have a crucial role in the reproduction of male authority and the preservation of dynastic rule. Although their unreliability requires their segregation, their sexual roles both for serving the needs of the king and, predominantly, for bearing heirs to the throne, require their access to the very core of dynastic power. It is because of this dual role that in most medieval misogynist works their presence becomes acute when the continuity of dynastic rule is at stake, and that their isolated space is, as it were, located in the centre of power. Although in many stories of this kind women not often appear as the mothers of male heirs, their appearing at the surface in times of dynastic succession is highly symbolic.

It is my argument that the figure of Shahrazad cannot be understood without considering the various components of this discursive prehistory, which places it within the tradition of the mirror for princes and fills it with the connotations of the narrative type of the malignant concubine. She conforms neatly to the stereotypes developed in this tradition, and the form, concept, and procedure of the Thousand and one nightsclearly reflect its generic conventions. What is more, Shahriyar unequivocally represents male dominance and royal prowess. However, in this case the female stereotype seems to deviate somewhat from her prescribed role. Somehow, Shahrazad succeeds in stepping out of the constraints of the stereotype which she is supposed to represent and escapes the fate of her predecessors. This is against all odds, since Shahriyar, even more rigorously than his predecessors, cedes to his impulses and even institutionalizes his aberration in a cyclic regime of sexuality and death. Inevitably, this regime in fact effectuates the disruptive influence of women which he aims to avoid, because it will precipitate the end of his dynasty. How does Shahrazad succeed in averting this seemingly unavoidable disaster?

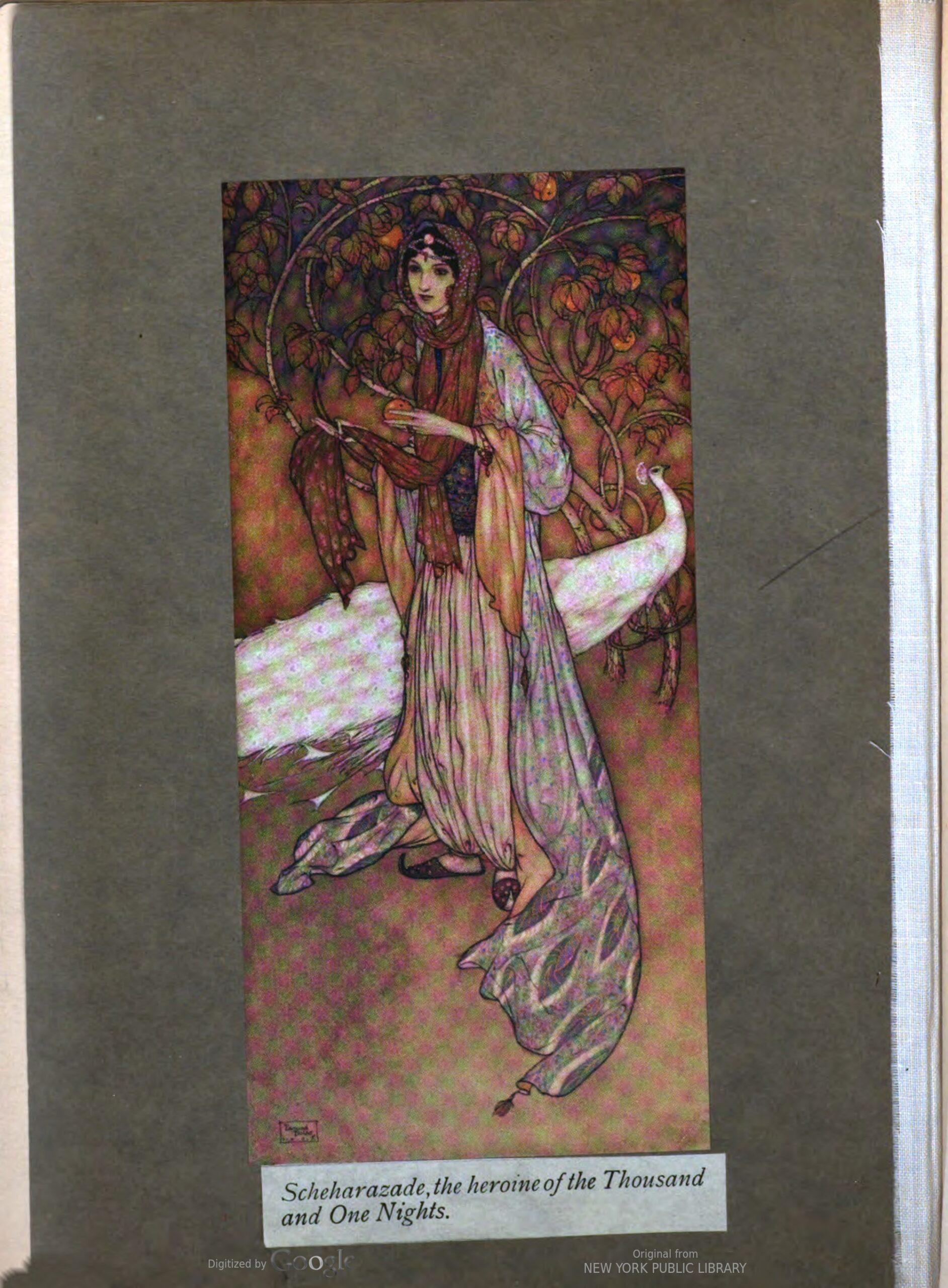

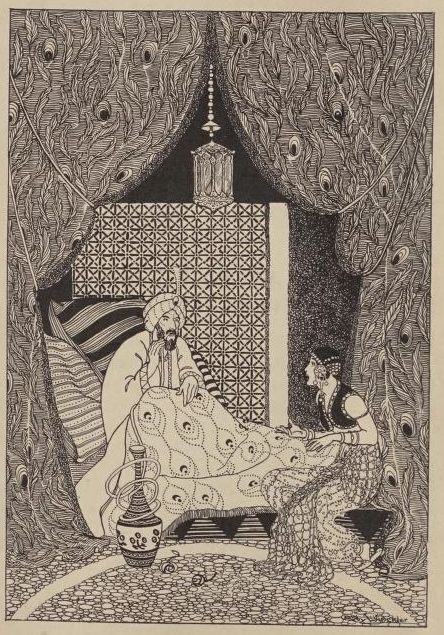

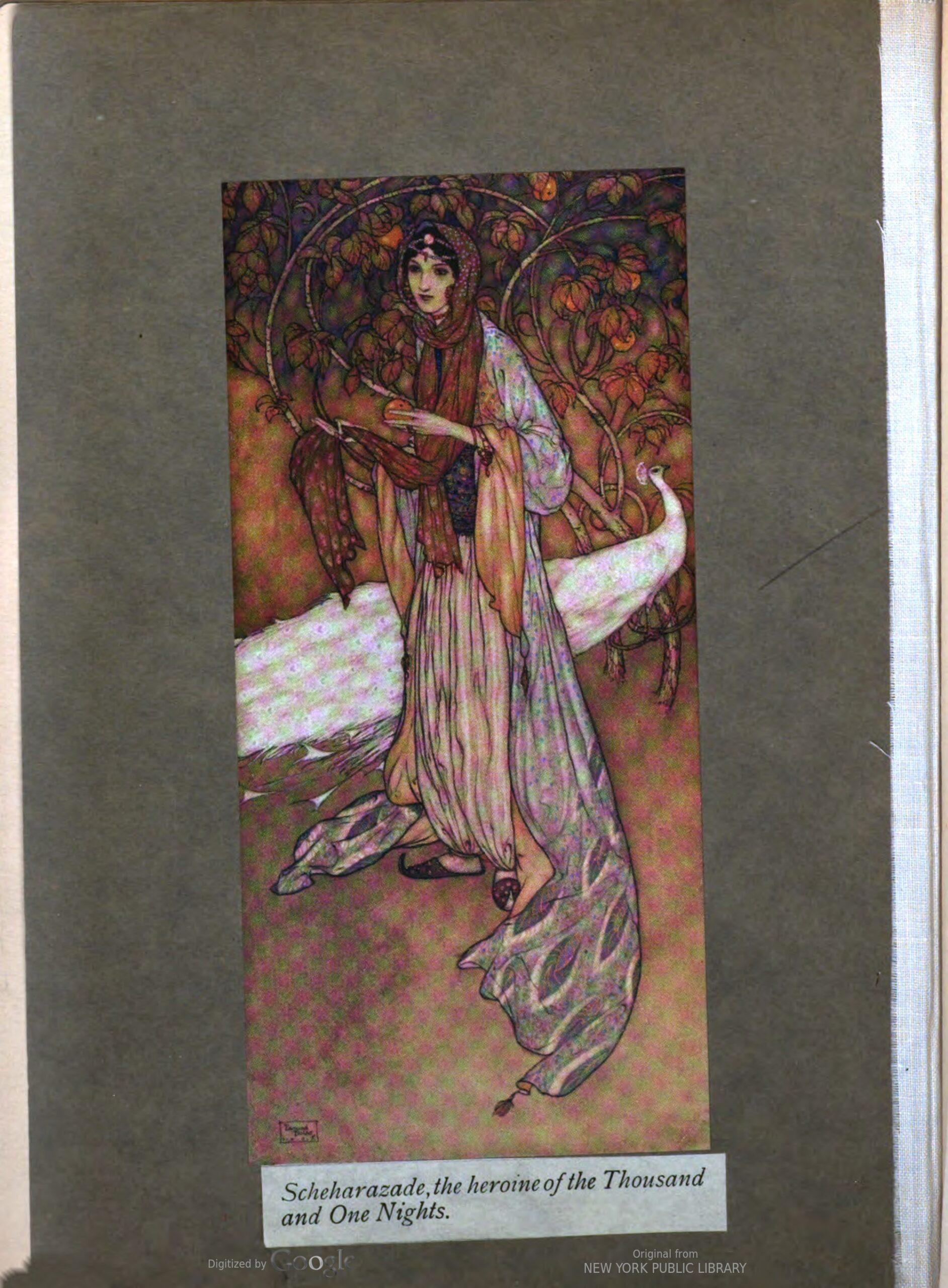

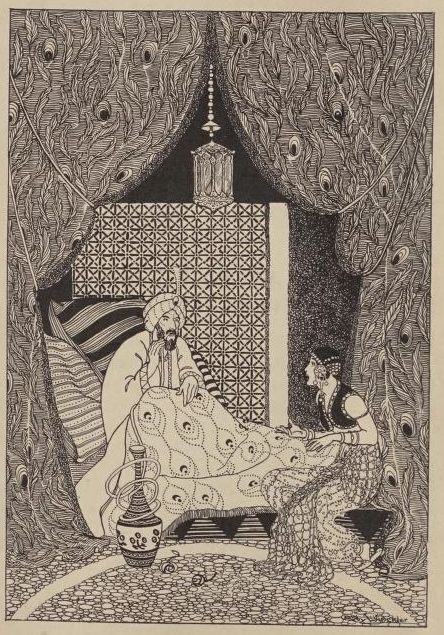

Shahrazad and Shahrayar in “The thousand and one nights, commonly called, in England, the Arabian nights’ entertainments.” A new translation from the Arabic, with copious notes. By Edward William Lane, 1889. Image via the Library of Congress.

If we compare the framing story of the Thousand and one nights with the cycles discussed above, we find not only some striking similarities, but also some crucial differences. First, the plot is not built around the maturation of a young prince and his preparation to accede to the throne; second, the threat to the kingdom is not caused by a concubine, but by the spouse of the king herself; third, the figure of the vizier is almost completely absent, being obscured by the assertiveness of his clever daughter. These deviations from the generic pattern are not coincidental; they are intended to confine the plot and its narrative effects to the two main protagonists, Shahriyar and Shahrazad. This implies a shift of focus of the story as a whole: instead of expounding primarily the stable principles of kingship and statecraft, the story focuses on the other, less formal, and more personal component of kingship, which is anchored in the relationship between the king and his spouse, or, more generally, between women and men. It is the king who is educated; it is the king who is directly confronted to the feminine aspect of life. Although the mechanisms of the mirror-for-princes are retained, the reference to traditional wisdom and conventions remains on the background and gives centre stage to both personal and symbolic relationship between Shahrazad and Shahriyar.

This shift of focus opens a wide array of narrative possibilities, which not only draw upon the misogynist conventions of the mirror-for-princes, but also explores the narrative component implied by the conventional intrigue, and link it to the personal, human component of kingship, to reach the same outcome in the end: the restoration of the regular cycle of dynastic reproduction. This setup breaks the pattern of stereotypes promulgated by the mirror-for-princes, and, I would argue, by parodying the generic type, the author aims to deconstruct these stereotypes by a less schematic, less emblematic, and more novelistic approach.

As in the mirror for princes Shahrazad evokes the tradition, conventions, and collective memory to restore a proper order, this time not based on abstract principles, but on acceptance of authority through examples of conflict resolution and displaying the diversity of human nature; and finally, Shahrazad soothes Shahriyar’s emotional and psychological distress by showing him how the imagination can heal wounds, through a combination of eroticism and narration. In this way, Shahrazad constructs the relations of power between her and Shahriyar. Like her predecessors, she fractures the discourse of masculine rationality, which in this case would lead to perdition, but she replaces it not with female irrationality, but rather with an alternative, perhaps female, rationality, which includes not only traditional principles, but also, significantly, the great heritage of the human imagination. The author makes this possible himself by inverting roles and by highlighting the narrative intrigue, stressing the importance of the imagination, not only by inserting tales, but by himself breaking up the female stereotype. Significantly, at the end Shahrazad shows the three children she has borne during the period of storytelling, thereby proving to Shahriyar that she has secured the continuation of the dynasty. However, it was not a prince who was educated, but the king, by establishing a new relationship between him and his spouse. It can be argued, therefore, that the story of Shahriyar and Shahrazad heralds the transition from a tradition of fossilized stereotypes to the use of more flexible protagonists, who are liberated from their rigid cultural connotations.

Aquamanile in the Form of Aristotle and Phyllis, late 14th or early 15th century. Image via the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Bibliography

Campbell, Killis, The seven sages of Rome, Ginn & company, Boston etc. 1907; reprint: Forgotten Books 2012.

Marzolph, Ulrich, and Richard van Leeuwen (eds), The Arabian nights encyclopaedia, 2 vols, ABC-Clio, Santa Barabara 2004.

Notes

1 Samarqandi (1986); Campbell (1907).

2 Marzolph, Ulrich/ Richard van Leeuwen (2004), vol. 1, pp. 160-1.

Shahrazad

On a previous occasion, I have argued that the Thousand and one nights, and especially the framing story, is related to the ancient genre of the mirror for princes, the tradition of wisdom literature developed particularly in Iran and the Middle East. This is suggested first by its form, a framing story containing a narrative intrigue, enclosing a series of embedded tales interacting with the frame in order to convey instructions to the king, the prince, and, of course, the reader. The example that comes to mind is the well-known cycle of the Seven viziers, whose origins go back to Sasanian sources, and which has been preserved in Arabic and Persian versions from the 10th-12th centuries.

The intrigue of the cycle is related to the motif of the ‘predator woman’ which can be found, for instance, in the story of Joseph and the wife of Potiphar, or Yusuf and Zulaykha, and is widespread in misogynistic texts in all pre-modern literary traditions. The story revolves around a young prince who may not speak for seven days – following a prediction – and is lodged in the women’s compound for that period. One of the concubines of the king attempts to seduce him into killing his father, usurping the throne, and marrying her. When the prince rejects the advances, she accuses him of having violated her. The king decides to execute the prince, but the viziers intervene. A trial ensues in which each of the viziers and the concubine in turn tell stories to support their case, until in the end, after seven days, the truth is discovered, and the concubine is punished.1

Rembrandt, Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife, etching, 1634 © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett.

“Yusuf and Zulaikha,” Folio 51r from a Bustan of Sa`di ca. 1525–35. Image via the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This cycle, which is incorporated in some versions of the Thousand and one nights, as ‘The craft and malice of women’2 seems to expand first on the nature of kingship and power. Repeatedly the viziers summon, or even beg, the king not to react impulsively and rashly, and examine the case thoroughly before pronouncing a verdict. They refer especially to two foundations of just and proper rule: rationality and the reservoir of wisdom preserved in the tradition. In their tales they refer to both, to soothe the anger of the king and show him examples taken from real life of how to behave properly in this kind of situations. The key word is continuity: proper rule can only be secured when the dynasty and ancient customs can be preserved and transferred to the prince. It is in the prince where ultimately the components of authority, dynastic legitimacy and just government should converge.

The reproduction of these components, which represent the regular order of things, is threatened by a highly disruptive phenomenon: a woman. The concubine has all the time been safely confined to the women’s quarter, but through the temporary presence of the prince the traditional boundaries between the various courtly domains become porous, and immediately her feminine properties begin to challenge these boundaries and affect the functioning of the state. She mobilises all her feminine assets: she tries to seduce the prince; she pretends weakness vis-à-vis male violence; she plays on the king’s emotions by appearing before him weeping and wailing, with dishevelled hair and torn clothes, appealing to his empathy, pity, and sense of justice. There is no doubt about the nature of the confrontation taking place here: It is the collision between a stable tradition of good governance dominated by male rationality and equanimity, and an inherently disruptive realm of femininity, governed by lust, treachery, irrationality, emotions, and disloyalty.

Phyllis and Aristotle, 1530, by Lucas Cranach the Elder. Via Wikimedia Commons.

The cycle of the Seven viziers belongs to a misogynist tradition associated with what is often called ‘The wiles of women’, of which there are several examples on the corpus of the Thousand and one nights. These stores suggest that the nature of women is somehow incompatible with statecraft, which is, therefore, the privilege of men. They seem to oppose the very idea of governance to some quintessential notion of femininity. This opposition is not just an excuse to construct a narrative plot; it is a fundamental division of male and female domains, which is at the basis of the moral and political order. It presupposes a set of opposites and incompatibilities, such as physicality vs. wisdom, rationality vs. emotions, treachery vs. loyalty, lust vs. self-restraint, which structures the discourse of power.

Image via the Internet Archive.

If we look at our examples, we can observe several common elements, especially in the Sanskrit, Persian and Arabic cycles. First, the stories are typically connected with the succession to the throne, and thereby with the tension between interruption and continuity. The coming of age of a prince signals the moment when the throne, with the principles, traditions and discourses supporting it, should be handed down to the next generation, a moment in history when the dynasty is particularly vulnerable. Second, the cycles show a remarkable pre-occupation with the motif of silence vs. speech, as a state which excludes a person from the clamorous affairs of everyday life. The tension which silence, the absence of speech, engenders, as an enclave segregated from regular life, is solved by narration, that is, the telling of stories which connect the contending visions with the realm of the imagination and a specific illustrative form of discourse. Third, the cycles are constructed as frame stories, integrating various narrative levels which reveal the process of instructing the king or prince, thereby instructing the reader as well.

Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove, Japan, Edo period (1615-1868). Image via the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

One of the characteristics of the feminine stereotype is that action is based not on principles, but on emotions, desire, egoism, lust, and short-term profit. Because of the nature of the concubine’s interference, an appeal is made to the king directed not merely at his authority as a king, but more particularly to his position as a man, a father, and the master of the household. What the concubine attempts is to draw the process of succession out of the schedule of proper procedures and subject it to the diverse emotions and desires which are hidden underneath them. The king is unable to neglect this appeal. He cannot just dismiss the matter as a female whim, because it is his responsibility, inherent in his male role, to protect his women and to exert his authority as a father. In the end it is the viziers who succeed in re-incorporating the dilemma, and the process of succession, into the regular, formal, procedure.

The impulsive reaction of the king, therefore, is no anomaly, but is rather prescribed by his dual role. It does not render him unfit to perform his task as a king, but rather reveals that kingship is not confined to an official role only and presupposes a complex amalgamation of different roles. As a man and a father, the king must show his moral indignation at the incident and respond in an emotional way. But as a king, too, it is required of him to show an emotional response. After all, these emotions buttress his privilege to pronounce an arbitrary verdict in any given situation, and confirms that his position is ultimately based on his right, or prerogative, or even duty, in some occasions, to use violence. Therefore, the impulsive nature of the king’s response lays bare the fact that he is not merely imprisoned in an official status, but is a human being, too. His power is based on the elementary manifestations of human nature. The opposition of the two – feminine and masculine – manifestations is finally re-integrated into the formalized system of procedures, ancient customs, traditional wisdom, and the requirements of reason. Women are relegated to the margins where they are supposed to abide.

The discordant circumstances of the prince’s education reveal that kingship is not monolithic and does not consist of complete arbitrary rule vested in the person of the king. Of course, the king represents the legitimacy of his descent, and the privileges projected on him by tradition, resulting in his position of power. However, kingship is a complex role consisting of various components, including not only the person of the king, and its connotations, but also the principles and conventions of tradition, represented by the viziers. These components interact in a dialogic relationship, the king imposing the power which he derives from his person and privileges, the viziers harmonizing these necessary features with the more durable contexts of tradition, reason and wisdom. It is these two components which in the end not only secure the transition from one king to the next, but which also, and perhaps more importantly, allow the transformation of power, as a necessary element of kingship, into authority, a manifestation which is not merely based on the exertion of power, but rather on the ideologically and socially accepted form of rule as it has accumulated in history, within the frameworks of morality, religion, collective memory and social harmony.

Image via HathiTrust.

In this construction of authority there is no role reserved for women. However, this is mainly an optical illusion, as the story itself seems to demonstrate. Like a building which is meant to keep specific enemies outside incorporates the idea of the existence and nature of these enemies in its design, concept and construction, the stronghold of kingship, designed to ward off feminine intervention, is fundamentally permeated with the female element. Because the stronghold is designed to keep the enemy out, the enemy is already inside. Although the women are enclosed in the women’s quarters, their segregation emphasizes their presence as an essential component, and their exclusion permanently implies the possibility of their – destructive – interference. A system which is constructed to exclude them, can inevitably survive only if their presence is continued. It is this paradox which is the main logic in the misogynist worldview conveyed in this type of narratives.

The feminine paradox, as described above, is not only conveyed by this type of literature in a concise form; it also represents the origins from which these narratives derive. After all, the intervention of the concubine generates the conflict and the phase of liminality in which all aspects of the kingship tradition and its antitheses are mobilized to restore order and secure the continuity of the state. It is the intervention of the concubine which brings to the surface the dialogic process on which authority is based, thereby fragmenting monologic, male, discourses of power. The concubine is the catalyst engendering a process of reconstitution of the dynasty, of the handing over of its traditional conventions, precisely by enforcing a rupture and threatening to discontinue it through regicide, patricide, and usurpation. As a result, the intervention allows for the display of the foundations of kingship which is ultimately meant for the education of the prince and, of course, the reader. It is no coincidence that this dialogic process is shaped as an exchange of tales: in the end it is narration which realizes the reconciliation between human nature and the eternal, socially accepted, principle of authority.

Within the perspective of the masculine vision of power and authority, on the one hand the marginalization and isolation of the feminine element is legitimized by the women’s alleged destructive and irrational influence. However, on the other hand, women have a crucial role in the reproduction of male authority and the preservation of dynastic rule. Although their unreliability requires their segregation, their sexual roles both for serving the needs of the king and, predominantly, for bearing heirs to the throne, require their access to the very core of dynastic power. It is because of this dual role that in most medieval misogynist works their presence becomes acute when the continuity of dynastic rule is at stake, and that their isolated space is, as it were, located in the centre of power. Although in many stories of this kind women not often appear as the mothers of male heirs, their appearing at the surface in times of dynastic succession is highly symbolic.

It is my argument that the figure of Shahrazad cannot be understood without considering the various components of this discursive prehistory, which places it within the tradition of the mirror for princes and fills it with the connotations of the narrative type of the malignant concubine. She conforms neatly to the stereotypes developed in this tradition, and the form, concept, and procedure of the Thousand and one nightsclearly reflect its generic conventions. What is more, Shahriyar unequivocally represents male dominance and royal prowess. However, in this case the female stereotype seems to deviate somewhat from her prescribed role. Somehow, Shahrazad succeeds in stepping out of the constraints of the stereotype which she is supposed to represent and escapes the fate of her predecessors. This is against all odds, since Shahriyar, even more rigorously than his predecessors, cedes to his impulses and even institutionalizes his aberration in a cyclic regime of sexuality and death. Inevitably, this regime in fact effectuates the disruptive influence of women which he aims to avoid, because it will precipitate the end of his dynasty. How does Shahrazad succeed in averting this seemingly unavoidable disaster?

Shahrazad and Shahrayar in “The thousand and one nights, commonly called, in England, the Arabian nights’ entertainments.” A new translation from the Arabic, with copious notes. By Edward William Lane, 1889. Image via the Library of Congress.

If we compare the framing story of the Thousand and one nights with the cycles discussed above, we find not only some striking similarities, but also some crucial differences. First, the plot is not built around the maturation of a young prince and his preparation to accede to the throne; second, the threat to the kingdom is not caused by a concubine, but by the spouse of the king herself; third, the figure of the vizier is almost completely absent, being obscured by the assertiveness of his clever daughter. These deviations from the generic pattern are not coincidental; they are intended to confine the plot and its narrative effects to the two main protagonists, Shahriyar and Shahrazad. This implies a shift of focus of the story as a whole: instead of expounding primarily the stable principles of kingship and statecraft, the story focuses on the other, less formal, and more personal component of kingship, which is anchored in the relationship between the king and his spouse, or, more generally, between women and men. It is the king who is educated; it is the king who is directly confronted to the feminine aspect of life. Although the mechanisms of the mirror-for-princes are retained, the reference to traditional wisdom and conventions remains on the background and gives centre stage to both personal and symbolic relationship between Shahrazad and Shahriyar.

This shift of focus opens a wide array of narrative possibilities, which not only draw upon the misogynist conventions of the mirror-for-princes, but also explores the narrative component implied by the conventional intrigue, and link it to the personal, human component of kingship, to reach the same outcome in the end: the restoration of the regular cycle of dynastic reproduction. This setup breaks the pattern of stereotypes promulgated by the mirror-for-princes, and, I would argue, by parodying the generic type, the author aims to deconstruct these stereotypes by a less schematic, less emblematic, and more novelistic approach.

As in the mirror for princes Shahrazad evokes the tradition, conventions, and collective memory to restore a proper order, this time not based on abstract principles, but on acceptance of authority through examples of conflict resolution and displaying the diversity of human nature; and finally, Shahrazad soothes Shahriyar’s emotional and psychological distress by showing him how the imagination can heal wounds, through a combination of eroticism and narration. In this way, Shahrazad constructs the relations of power between her and Shahriyar. Like her predecessors, she fractures the discourse of masculine rationality, which in this case would lead to perdition, but she replaces it not with female irrationality, but rather with an alternative, perhaps female, rationality, which includes not only traditional principles, but also, significantly, the great heritage of the human imagination. The author makes this possible himself by inverting roles and by highlighting the narrative intrigue, stressing the importance of the imagination, not only by inserting tales, but by himself breaking up the female stereotype. Significantly, at the end Shahrazad shows the three children she has borne during the period of storytelling, thereby proving to Shahriyar that she has secured the continuation of the dynasty. However, it was not a prince who was educated, but the king, by establishing a new relationship between him and his spouse. It can be argued, therefore, that the story of Shahriyar and Shahrazad heralds the transition from a tradition of fossilized stereotypes to the use of more flexible protagonists, who are liberated from their rigid cultural connotations.

Aquamanile in the Form of Aristotle and Phyllis, late 14th or early 15th century. Image via the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Bibliography

Campbell, Killis, The seven sages of Rome, Ginn & company, Boston etc. 1907; reprint: Forgotten Books 2012.

Marzolph, Ulrich, and Richard van Leeuwen (eds), The Arabian nights encyclopaedia, 2 vols, ABC-Clio, Santa Barabara 2004.

Notes

1 Samarqandi (1986); Campbell (1907).

2 Marzolph, Ulrich/ Richard van Leeuwen (2004), vol. 1, pp. 160-1.