PDF

Download

Citations

Click and drag then release to select a passage to cite.

Annotations

How to submit annotations to Mizan Journal articles:

your work is published.

Search within

ISIS, Eschatology, and Exegesis

The Propaganda of Dabiq and the Sectarian Rhetoric of Militant Shi’ism

Image

Audio

Video

Chart or Graph

ISIS, Eschatology, and Exegesis

The Propaganda of Dabiq and the Sectarian Rhetoric of Militant Shi’ism

Introduction

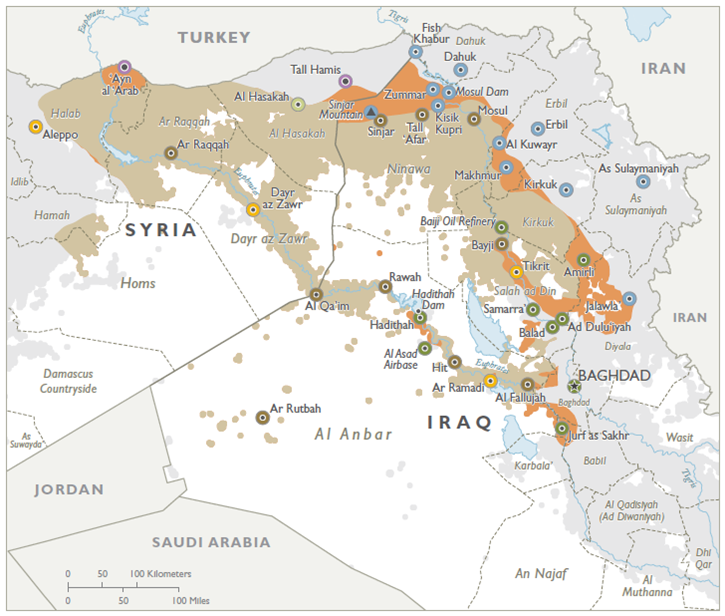

The emergence of ISIS on the world stage seems unprecedented in modern Islamic history.1 In political and military terms, the rapid evolution of the movement from an insurgency to a territorial state, or at least a quasi-state entity with pretensions of actual governance, that also maintains a terror network of significant profile and impact, is an utterly unexpected development in the sordid recent history of radical jihadism (see Gallery Image A).2 Further, two aspects of ISIS’ policy are especially surprising, making it seem rather atavistic among modern Islamist movements. First, its brash declaration of a caliphate—with aspirations of universal recognition by the worldwide community of Muslims, however unrealistic this might be—is not entirely unprecedented, though arguably ISIS has a far more credible claim to have restored khilāfah, at least in the eyes of jihadist enthusiasts, than other movements before them who claimed to have done the same.3 Second, not only has ISIS taken possession of actual territory over which it claims to rule, but it has rejected the national boundaries established in the Middle East in the early twentieth century by the Sykes-Picot Agreement and subsequent treaties.4 Instead, ISIS aspires to establish a territorial state based in the Jazīrah, a naturally contiguous zone incorporating northwest Iraq, northeast Syria, and southeast Turkey and traversing those states’ recognized borders.5 Moreover, in cultural, religious, and intellectual terms, many aspects of the group’s ideology and praxis—the relentless resort to takfīrThe act of one Muslim asserting that another Muslim, on the basis of beliefs or actions, is actually not a Muslim but rather an infidel (kāfir)., the revival of slavery, the public administration of extreme and appalling forms of corporeal punishment (some unprecedented in modern times)—have been so radical as to have drawn condemnation not only from virtually all state actors in the Middle East but even from Al-Qa’idah and other militant organizations.6

However, in this article, I will argue that some aspects of the ISIS phenomenon appear more familiar when we consider them in deeper historical perspective—especially if we are attuned to the predictable logics that have typically attended Muslim groups’ embrace of violence against their coreligionists. In particular, here I will show that in its propaganda, ISIS uses themes and images drawn from the Qurʾān, as well as certain familiar tropes and topoi of Islamic history, for the specific purpose of ‘othering’ fellow Muslims and smearing them as unbelievers, thus marking them as legitimate targets for conquest and slaughter. Other Muslim movements have made similar exegetical moves based on the Qurʾān and tradition, under similar circumstances.

The irony here—one that ISIS ideologues and spokesmen would surely not appreciate—is that they have specifically recapitulated the discursive and exegetical gestures associated with a sect of the Shi’ah that engaged in a very successful statebuilding project in the tenth century. This is the Fatimid Empire, founded by a branch of the Isma’ilisOne of the major branches of Shi’ah, each distinguished by the specific lineage of Imāms from the family of Muḥammad whom they follow. that established a caliphate based in North Africa and Egypt, dominated the eastern Mediterranean for two hundred years, and rivaled (and for a time eclipsed) the Sunni caliphate of the Abbasids based in Baghdad. ISIS’ tendency to execrate Shi’ah as false Muslims, apostates and infidels, does not diminish the utility of this comparison. As we shall see, throughout the history of sectarian conflicts in Islam, Sunni and Shi’i communities have often resorted to similar, if not the same, modes of discourse and made analogous rhetorical claims, especially in the process of denouncing and delegitimizing each other.

Nor is it insignificant that this extreme rhetoric has accompanied an explicit promotion of baroque fantasies of the end of the world.7 The ISIS propaganda machine strives to depict the rise of its caliphate as the fulfilment of prophecy, exploiting various developments in its campaigns against Iraqi state entities and rival insurgent groups operating in the Syrian conflict zone as major milestones in the timetable of events leading up to the End Times. Its military successes are deftly manipulated through various propaganda outlets, particularly social media, as political theater to bolster its religious credentials among supporters. The claim to be fulfilling an apocalyptic timetable has proven particularly successful for the recruitment of foreign fighters; many of the jihadists who travel to Iraq and Syria style themselves as muhājirūn, after the original Muslim emigrants who joined Muḥammad on his hijrah from Mecca to Medina, or ghurabāʾ, ‘foreigners’ or ‘strangers,’ exploiting the prominent role assigned to the gharīb in traditional end-time prophecies. Likewise, the apocalyptic associations of various locales in the Syrian landscape, especially Dabiq (the Islamic version of Armageddon), allow ISIS to recast victories of little strategic value as significant triumphs in their propaganda.

Chiliastic anticipation has frequently enabled upstart movements to overthrow established regimes and seize power in Islamic history, and apocalyptic rhetoric has particular utility for casting one’s opponents and critics as servants of the Antichrist and minions of the Devil whose inevitable defeat has long been foretold. Moreover, we must recognize that when it is analyzed in a broader sociological frame, the extreme apocalyptic rhetoric of this so-called Islamic State cannot responsibly be characterized as an exclusively Islamic phenomenon. Rather, it is common to many radical groups affiliated with different religious communities found in the contemporary world, especially those seeking to harness millenarian enthusiasms in the service of aggressive statebuilding projects.

Fatimid statebuilding and millenarian eschatology

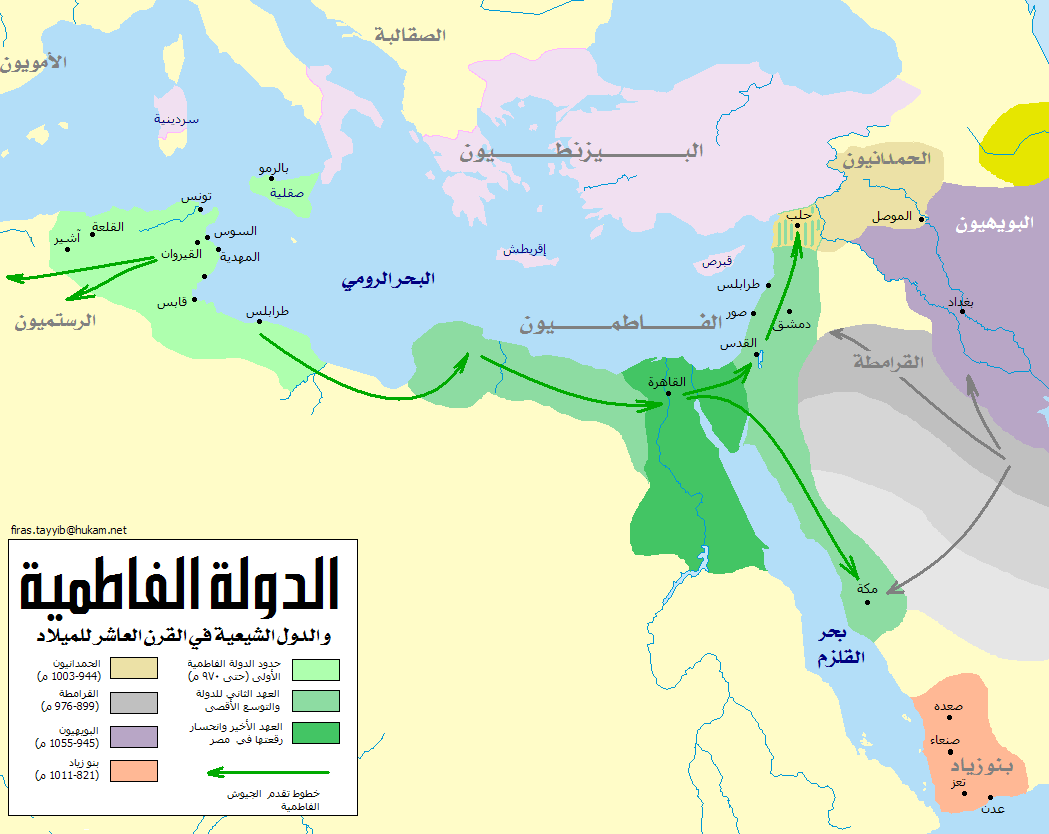

The spectacular achievements of the Fatimid Empire, both in terms of fostering a rich intellectual tradition and promoting a material culture of astonishing vigor and sophistication, are well known. At the height of their power, the Fatimids’ immediate sphere of influence encompassed not only their heartland in Egypt and North Africa but much of Palestine and Syria, southern Italy, and Sicily; their cultural impact and political reach extended as far as Spain in the west, Yemen in the south, and Iraq in the east (see Gallery Image B). Most famously, the Fatimids founded the city of Cairo in 969 and established the Azhar—once a thriving center for the propagation of Isma’ili doctrine and today a Sunni madrasa universally considered one of the leading institutions of religious learning in the Islamic world—in 972.

What is most worthy of our attention here are the Fatimid dynasty’s beginnings. Though the movement’s origins in the late ninth and early tenth centuries are shrouded in a haze of hagiography and mythology, the surviving accounts still allow us to draw some solid conclusions about the nature of the group and its ideology. Like ISIS, the Fatimid regime originated in an insurgency, as one of many Isma’ili groups fomenting rebellion against the Abbasids and their governors throughout the Islamic world on behalf of the Alid imāms in the wake of the disappearance or ‘occultation’ (ghaybah) of the Twelfth Imām in 874. The propaganda campaign and mobilization efforts of one Isma’ili faction operating in North Africa bore fruit in 909, when a coalition of interests supported by the military power of the Kutamah Berber tribal coalition conquered the province of Ifriqiyyah (modern Tunisia) from the Aghlabids, the Abbasid governors of the region, and openly proclaimed the establishment of a new Shi’i caliphate.8

Within a century the Fatimids had conquered Egypt, constructed a new capital city—al-Qāhirah or Cairo—and asserted their dominion over most of the Islamic world from the Levant westward. In this they presented a vigorous counterpart to the senescent Abbasid dynasty, which had already experienced a significant deterioration of its political (if not moral) authority in Iraq, as well as a significant challenge to Sunni claims about the caliphate. It has also often been observed that it was under the Fatimids that extensive networks of cultural and economic exchange throughout the Mediterranean were established or revived, thus fostering intercontinental trade and travel from Western Europe and so eventually paving the way for the eastward campaigns and migrations of Latin peoples during the Crusades.

Aside from these specific political and military details, a distinctive aspect of the Fatimid rise to power is their reliance on millenarian eschatology in their ideology and propaganda. The Fatimid caliph-imāms claimed to be descended directly from ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib and Fāṭimah, the daughter of the Prophet Muḥammad, and clearly presented their rise to power as a transformative millenarian event in world history. This was signaled, above all, by the fact that the first Fatimid caliph-imām, ʿAbd Allāh, took the regnal title of “the Rightly-Guided One” or MahdīOr 'Guided One,' a messianic figure who will marshal the true Muslims and stand as God’s champion in the final conflict that will precede the advent of the Last Judgment., thus exploiting the fervent belief among the partisans of the family of the Prophet that their redemption was imminent.9 As we shall see, the parallel with ISIS here is exceptionally striking, for the Islamic State’s propaganda claims that the end of the world is immanent, the establishment of its caliphate and its campaigns of conquest in Iraq and Syria serving as proof of its fulfillment of prophecy in playing a key role in the dramatic events leading up to the Hour, the Islamic eschaton.10

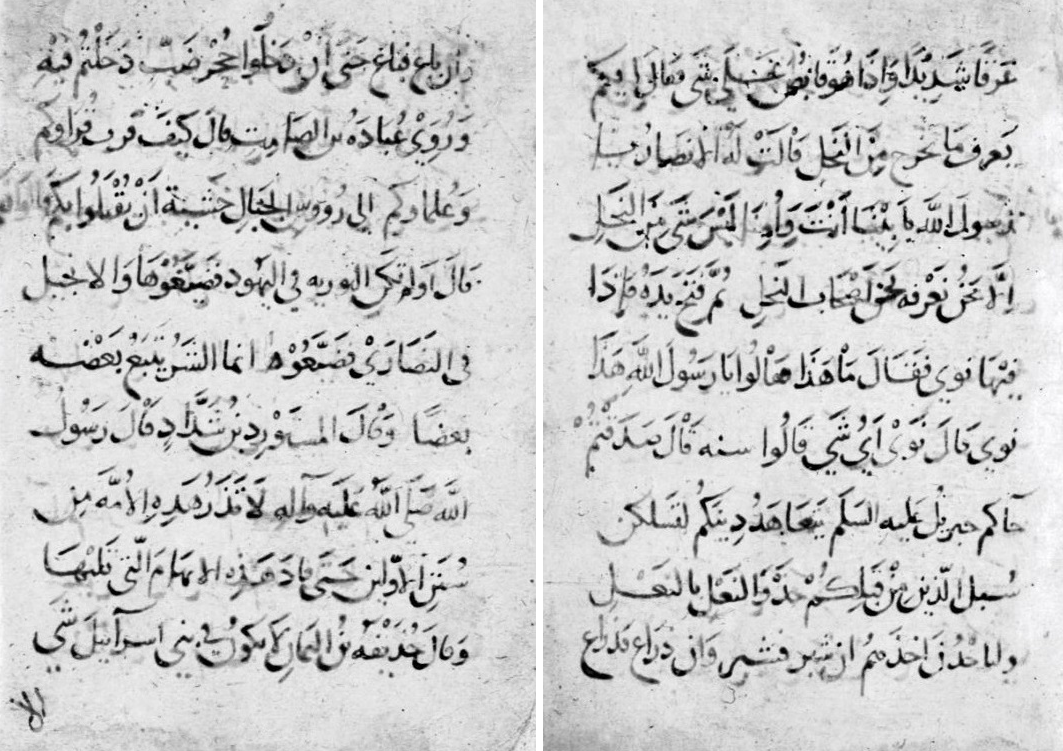

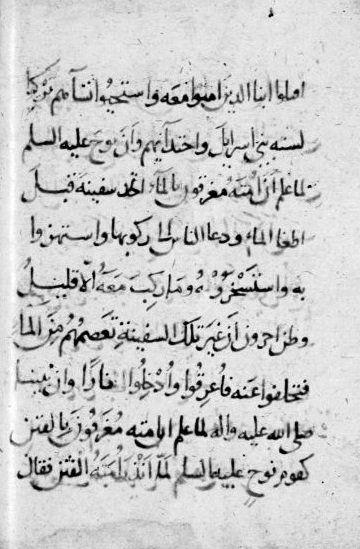

An anonymous manuscript in the Arabic collections of the British Library (BL Or. 8419) offers us a unique glimpse of early Fatimid propaganda and its complex interweaving of qurʾānic prooftexts, biblical and Islamic history, sectarian claims, and millenarianism.11 This anonymous work is non-technical in nature, which distinguishes it from most texts associated with the Isma’ilis in general and the Fatimids specifically. It addresses itself to an ordinary, though literate, Muslim audience and does not rely on either veiled language or esoteric arguments comprehensible only to initiates to support its main points—a conspicuous marker of Isma’ili tradition already in the formative period of the ninth century, and a signal feature of most of the surviving literature associated with the Fatimids.12 Rather, on the basis of Qurʾān and ḥadīth alone, this work argues that although the Muslim community originally followed the guidance of the Prophet Muḥammad, they have now gone astray like other communities that went before them, particularly the Jews. It is only the Shi’ah who follow the correct path, and so constitute a kind of saved minority, as opposed to the masses who might call themselves Muslims but are really no better than Jews or the idolaters and hypocrites who opposed Muḥammad and his family during their lifetimes.

The text makes this argument by drawing on a group of ḥadīth that may collectively be called the “Sunnah Tradition.” 13 Alluding to or explicitly citing qurʾānic references to the communities and nations that preceded the coming of Islam, these traditions depict Muḥammad outlining the essence of Islam for his followers and asserting its superiority to other paths; but he also issues a stern warning that his community will go astray just as older communities did. Most often this warning is phrased as a prophecy that the Muslims “will follow the path of those who came before you”; the term for path here is usually sabīl (pl. subul), but in some variations it is sunnah (pl. sunan), and sometimes the path is explicitly noted as the path of Israel (sunnat banī isrāʾīla)—meaning that the Muslim ummah, or at least part of it, is doomed to repeat the errors of the Jews and Christians who preceded them.

The Fatimid text cites a number of variations on this ḥadīth (see Gallery Image C):

لتسلكن سبل الذين من قبلكم حذو النعل بالنعل ولتأخذن اخذهم ان شبر فشبر وان ذراع فذراع وان باغ فباغ حتى ان دخلوا جُحر ضَبّ دخلتم فيه

[The Prophet said:] “…You will surely travel along the paths of those who came before you, walking in their footsteps; you will surely follow their example, every inch, every foot, every mile they traveled—to the degree that if they entered a dark lizard hole, you’ll do it too.”14

Across the centuries this tradition has been used in a number of ways. It is commonly cited in connection with Muḥammad’s prophecy that his community will split into seventy (or seventy-two) sects, as our author acknowledges:

فانذر رسول الله صلى الله عليه وسلم وآله امته الفرقة والاختلاف واعلمهم انهم سيركبون ما ركبت الامم الّذين من قبلهم فقال عليه وعلى آله افضل السلم لتركبن سنّة بني اسرآيل حَذْوَ النعل بالنعل والقذّة بالقذّة

So did the Prophet warn his community against factionalism and differing among themselves (al-furqah wa’l-ikhtilāf); and he informed them that they would surely do as the communities who came before them had done. Thus he said: “You will surely follow the sunnah of Israel, measure for measure and like for like.”15

This tradition is also very commonly cited as the basis for the polemical claim made by Sunni authors that the Shi’ah are “the Jews of our community” (yahūd ummatinā). As Wasserstrom has demonstrated in his classic discussion of this tradition, a variety of Sunni authors drew on this trope to characterize the Shi’ah as erring in both belief and practice in recognizably ‘Jewish’ ways.16

However, the Fatimid text provides an intriguing example of how Shi’ah could make use of this tradition in an analogous way, but for the opposite purpose of delegitimizing the path followed by those who rejected their claims and the cause of the Alids.17 The text is distinctive for the systematic way in which it draws parallels between events in biblical, prophetic, and early Islamic history and the situation of the Shi’ah in the author’s present (most likely the early tenth century). Sometimes this is done through simile: for example, it compares Pharaoh and the Egyptians who oppressed the Israelites and the “oppressors of the family of Muḥammad” who victimized the imāms and their followers.18 At other times the telescoping of history is accomplished through metaphor: the persecutors of the family of the Prophet and their supporters—i.e., Sunnis—are labeled idolaters and tyrants, “the Pharaohs of Quraysh.”

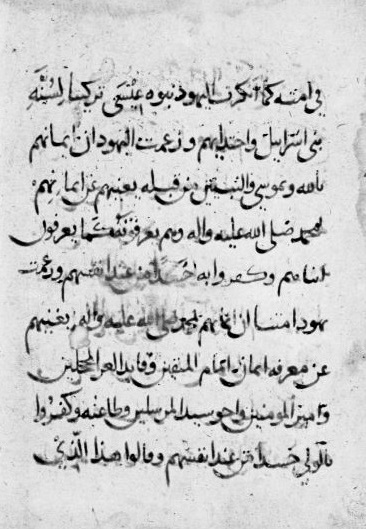

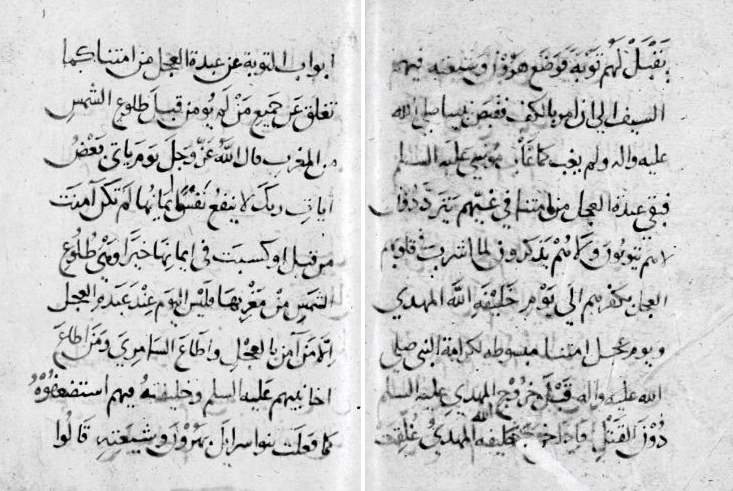

In still other instances, the pejorative appellation “the Jews of our community” appears, a clear reversal of the trope of the Shi’ah as the Jews of the community as it is commonly deployed in Sunni polemic. As the Fatimid text develops this image, the persecution of the Alids and their loyal partisans, the Shi’ah, marks Sunnis as oppressors and infidels. Their denial of the claims of the Alid imāms as sole legitimate leaders of the community hearkens back to the Jews’ denial of Muḥammad’s claims, one of many ways they are like Jews and no better than Jews (see Gallery Image D):

وزعمت اليهود ان ايمانهم بالله وبموسى والنبيين من قبله يغنيهم عن ايمانهم محمد صلى الله عليه واله… وزعمت يهود امتنا ان ايمانهم بمحمد صلى الله عليه واله يغنيهم عن معرفة ايمان امام المتّقين

The Jews allege that their faith in God and in Moses and the other former prophets suffices for them, so that they do not need faith in Muḥammad… Likewise the Jews of our community claim that their faith in Muḥammad suffices for them, making unnecessary faith in the Imām of the God-fearers [i.e. ʿAlī]…”19

This telescoping of history, the alignment of the travails faced by the pre-Islamic prophets and their loyal followers, the Prophet Muḥammad and his family, and the Alid imāms and their partisans the Shi’ah, particularly in the author’s present, is typical of the ‘hiero-historical’ perspective found in Fatimid texts. Like other Shi’i movements of the time, the Fatimids distinguished between the ẓāhir or external meaning of scripture and ritual and the inner, essential meaning, the bāṭin, which could be disclosed only through exegesis by delegates of the inspired imāms, to whom God had entrusted true knowledge. This exegesis of the inner dimension of scripture—the spiritual, but also frequently political, interpretation accessible only to a few—is termed taʾwīl, disclosure of the essence or ‘foundational’ meaning.20

What makes this typological exegesis of the Fatimids and other Shi’i groups so powerful is that it embeds the present in a kind of timeless scriptural now: contemporary experience is not so different from that of bygone days, and the present appears as the natural culmination of the scriptural past. The oppression of evildoers in all ages is the same; the suffering of the faithful in all ages is the same. The political implications of scripture are brought to the fore. Pharaoh oppressed the Israelites; the Jews persecuted Jesus and the apostles; the hypocrites and idolaters opposed Muḥammad; the Umayyads slaughtered the imāms of the family of the Prophet. Throughout history, the pattern recurs until the time of the Mahdī, who like Moses will punish the idolaters and redeem the Shi’ah, bringing them to their Promised Land.21

Thus, this anonymous propaganda text is unusual in that it both offers a window onto the ideology of the Fatimids in the foundational period of their history, when their embrace of violent revolution was most conspicuous, and presents a set of rhetorical features intended to be legible and even appealing to a wide public due to their grounding in qurʾānic texts and early Islamic history. In what follows here, I will observe a number of striking parallels between claims and ideas promoted by ISIS and those of the early Shi’ah in general and the Fatimid movement as exemplified by this work in particular.

It is important that we be clear about the nature and purpose of our comparison of ISIS with this militant Shi’i dynasty. After all, ISIS is a militant Sunni organization whose genealogy is more commonly traced back to precursor insurgent movements of a radical Salafi orientation, though its ideology involves a reliance on takfīr and a willful targeting of Muslim civilians that even Al-Qa’idah and its various offshoots and affiliates reject. Further, drawing parallels between Muslim groups separated by a millennium may seem dangerously ahistorical to some. Our point here, however, is that the ultra-militant vision of Islam and Muslim community held by the spokesmen of ISIS and expressed in their propaganda is not only contrary to the ethos of Sunnism as it has been conventionally defined throughout its history, but, if anything, hearkens back to the militant and perfectionist conception of Islam held by early sectarian groups.22 The ideology of the Fatimid Caliphate thus furnishes a thousand year-old precedent not only for ISIS’ rapid transition from an insurgency to a successful statebuilding project, but also for important aspects of their doctrine and propaganda as well. As we shall see, the results of such comparison are illustrative and provocative.

ISIS’ sectarian apocalypse

Despite its officious claims to be the legitimate heir to and revival of the long-defunct Sunni caliphate, the ISIS movement is quite demonstrably deviant in terms of the standard set of values and practices historically associated with Sunnism. Its spokesmen present themselves as restoring the golden age of imperial Islam, particularly the period of the Rashīdūn or “Righteous Caliphs” who ruled for the first thirty years of Islamic history, that period during which apostolic Islam was supposedly at its strongest and purest. They are also quite nostalgic for the high Abbasid period, the apogee of the Sunni caliphate as an institution and a world power. This is surely not accidental given that the Abbasids represented the pinnacle of caliphal power in Iraq in particular, ruling from Baghdad for just over five hundred years—first as a vigorous, expansionist state, and then, after a long period of decline in the ninth and tenth centuries, as a severely attenuated, but still nominally and symbolically authoritative, shadow of its former self.23 However, the ideology of ISIS—now broadcast through various means as part of a sophisticated propaganda machine heavily reliant on social media networks in particular—actually more closely resembles that of the Fatimids in their early history than that of the classical Sunni caliphate.

ISIS most clearly resembles the Fatimid precursor in the conspicuous conjunction of two elements in its rhetoric and propaganda: an immanent or already realized millenarianism and an unambivalent embrace of violence against other Muslims. Regarding the first, it is entirely clear from the various propaganda statements ISIS has made through a variety of outlets that its leadership views itself—or at least presents itself—as having fulfilled a number of traditional prophecies concerning a sequence of political events that are understood to be harbingers of the fitan or struggles of the End Times, which will eventually usher in the arrival of the Mahdī and the conflicts that will culminate in Judgment Day.24 As already noted, the Fatimids claimed that the caliph who established their rule in North Africa in 909 was the Mahdī, and that their caliphate represented both the culmination of history and the transformation of the world order. Millenarian anticipation has frequently been a conspicuous feature of modern Shi’i movements as well, especially the theocratic regime of the Islamic Republic of Iran, which appears to stem from a longstanding emphasis on a chiliastic or messianic political ideology among modern Twelvers in particular.25

In contrast, the ideologies of Salafism and Wahhabism that have generally provided the doctrinal resources for Sunni jihadist groups have historically been far less prone to apocalypticism and messianism.26 ISIS has enthusiastically adopted an apocalyptic orientation that has had some traction in the Sunni world for a number of decades now, one that is given credibility and authority through reference to a corpus of eschatological ḥadīth that have always had an ambiguous status in Sunni learned circles. Thus, ISIS claims that the caliphate of Abū Bakr al-Baghdādī is a crucial step on the path towards the apocalyptic final battle between the forces of Islam and “Rome” (the West) that will culminate in the end of the world and the ultimate triumph of Islam.

While the leadership cadres of older Sunni movements fostering international jihad like Al-Qa’idah have at the very most only hinted that their struggles have apocalyptic significance, millenarian tendencies have been simmering in the rank and file of the jihadist underground for some time now.27 The centrality of such claims in ISIS’ propaganda and doctrine may be due to these ideas gaining greater purchase throughout the Islamic world in general over the last decade, or in the jihadist underground more specifically. Admittedly, it is also possible that such ideas have been prominent for some time, or even on the upswing, and simply escaped the notice of outside commentators until recently. ISIS’ tendency to broadcast its ideology primarily in English through various propaganda channels has served to remove whatever ambiguity about their goals and motivations might have formerly prevailed in the Western media.28

The second major area of similarity between ISIS and the Fatimids is the former’s unambivalent willingness to not only harm other Muslims, but to actually make use of various rhetorical instruments to deny their status as Muslims to justify aggression against them. In early Islamic history, the reigns of the Rāshidūn and the Umayyads thrived on the massive successes of their campaigns of conquest against pagan Arab tribes, other polities in Arabia, and then the Eastern Roman and Sasanian empires. Under the Abbasids—whose rise was in no small part due both to the decline of the expansionist military order upon which the Umayyads had depended and the redirection of potent military forces in the east back towards the center for the purpose of regime change—outward expansion of the borders of the Islamic world slowed.29 However, even the Abbasids conducted regular jihad against the Byzantines and other neighboring polities and legitimated themselves thereby. This was also true of the new Muslim states that gained autonomy as the central authority of the Abbasids gradually broke down, for example the breakaway Umayyad state in Spain that openly declared its claim to be the legitimate caliphate in 929 and flourished for a century, largely by preying upon much weaker Christian principalities in the north.

Other, more recent Muslim statebuilding enterprises—some of them caliphates—were forced to sustain themselves and expand by waging war against communities of their fellow Muslims, legitimizing this in a variety of ways. From the Middle Ages to the early modern period, jihads were proclaimed in numerous places throughout the Islamic world, as often to muster religious support for offensive or defensive campaigns against Muslim powers as to expand the borders of the dār al-Islām at the expense of neighboring Christian principalities, or defend against Christian expansion at Muslim expense. What a survey of the different circumstances in which jihad was proclaimed from the thirteenth century onwards reveals is that various Muslim religious authorities were willing to justify expansion of their states or communities by victimizing their fellow Muslims, usually by finding ways to describe their Islam as somehow not genuine or deficient in some significant way. Ibn Taymiyyah, who legitimated Mamluk warfare against the Ilkhanids of Iran, offers the classic example of this tendency. Unsurprisingly, many modern jihadist movements draw on Ibn Taymiyyah’s work to legitimate insurgency against Muslim regimes.30

What seems to distinguish ISIS as a modern version of this phenomenon is its continuation of older, pre-modern tendencies synthesized with more contemporary jihadist ideology, especially their propounding of radical takfīr as the justification for fostering a state of war against infidels and Muslims alike, including lethal aggression against Muslim state entities, rival jihadist insurgencies, and even civilian populations. The recent study of Rajan vividly describes the significant transitions that have occurred in the international jihadist movement with the shift from Al-Qa’idah and its affiliates, who generally maintained a disciplined resistance to takfīr in favor of garnering popular support among the widest possible Muslim constituency, and the full-throated embrace of takfīr by ISIS and its affiliates, which Rajan characterizes as nothing short of genocidal.31

The extreme behaviors embraced by ISIS, more radical and savage than practically any Islamist group previously known, has provoked substantial debate in some circles as to whether or not ISIS is authentically “Islamic.” The debate centers on whether one sees ISIS as an outgrowth of certain prevalent trends in Islamic history, particularly older forms of militant Sunnism, or rather one sees their extremism as simply placing it beyond the bounds of anything one might legitimately call “Islam,” defined by the historical experience and beliefs of Muslim communities throughout the world as well as the majority consensus on how Islam and Sunnism should be defined.

This debate is deeply inflected by the larger social and political context in contemporary North America and Europe, in which Islamophobic institutions and ideologues compete for the political capital that accrues to parties that rail loudly against the “Islamic threat.” This has the effect of marginalizing minority Muslim communities in Western societies that struggle to dissociate themselves from ISIS and other radical groups in the public eye, yet are continually subject to the kinds of hostility and discrimination that not only alienates the moderate majority but can radicalize more vulnerable and less assimilated elements at the edges of those communities. Thus, the academic debate over whether ISIS’ deviance from so many norms renders it essentially beyond the pale of what can reasonably be recognized as Islam has occurred against a background of implicit or even explicit claims that ISIS and other violent movements actually epitomize Islam—a contention that any objective observer would find both historically and conceptually untenable, yet has repeatedly been revived by right-wing politicians in France, America, and other Western countries.32

There is some irony to this situation, because ISIS spokesmen themselves are intensely interested in the question of who is and isn’t really Muslim and what is or isn’t legitimately Islam. In fact, it is their extreme rhetoric on this issue that is one of the hallmarks of the ISIS movement, and marks it as completely aberrant in traditional Sunni terms. Predictably, the ISIS movement’s definition of “true Islam” is a rather narrow one. At various points in its history the movement has alienated various allies—to say nothing of larger Muslim publics, even those sympathetic to Islamist insurgency—on account of its willingness to target civilians and brand rival groups as apostates as a pretext to justify intimidation and actual aggression against them.33 Yet radical groups seldom if ever concede that they actually are radical, and ISIS is no exception. Rather, they use nomenclature in a subtle way to cast their positions as original, authentic, and essential to Islam, while characterizing those who hold different opinions and insist on a different definition of Islam to be outsiders and deviants.

Thus, in its propaganda, the movement frequently refers to itself and its followers simply as “the Muslims,” though this term is restricted to those who support their cause and claims, accept their authority, and acquiesce to living under their rule. By labeling the subjects of their caliphate simply as “Muslims,” ISIS both naturalizes the concept of its sovereignty and presents itself as authentically Islamic and perfectly mainstream: they are the Islamic State, defined by their claim of authority over “Muslims” in general, commensurate with the traditional conception of caliphal sovereignty as universal. In contrast, those who resist, object, or pledge their loyalty elsewhere are marked as deviant and sectarian using a host of familiar labels such as murtadd (apostate) or munāfiq (hypocrite), and seldom if ever dignified by being recognized as Muslims.34

Somewhat more obscurely, ISIS propaganda refers to Shi’ah—whether Iraqis or Iranians—as “Ṣafawīs,” or “Safavids.” This is a reference to the dynasty that ruled Iran from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century, during which time the majority of the country was converted to Twelver Shi’ism.35 This label serves three rhetorical purposes. First, like the other labels for noncompliant or “deviant” Muslims employed by ISIS, it brands Shi’ah as something other than simply Muslim, emphasizing Sunnism as the norm or mainstream that ISIS represents and from which its opponents deviate. Second, it asserts a relatively recent origin for Shi’i communities in the area, despite Shi’ism’s long history in Iran and especially Iraq, in contrast to the original form of Islam that ISIS would claim its particular interpretation of Sunnism represents.36 Finally, it links Iraqi Shi’i communities to Iran, marking them as foreign and outsiders, in contrast to the native Iraqi origins of much of the ISIS leadership (never mind the fact that Abū Muṣʿab al-Zarqawī, ISIS’ spiritual godfather, was a Jordanian and many of its supporters are foreigners or at least foreign-born).37

Historically, one of the classic characteristics of Sunnism is its big tent ideology—a rejection of sectarianism and embrace of diversity of opinion. However, there is a perennial tendency found among some Sunni authorities to emphasize Sunnism as original and essential, “true” Islam, at the expense of that very avoidance of extremism and acceptance of diversity that is at the core of historical, majoritarian Sunnism. It is these elements within the Sunni fold that have gravitated towards takfīr as a means of imposing their views, enforcing compliance with their definition of orthodoxy, and policing the boundaries between what they define as true Islam and error. The paradox is that labeling a fellow Muslim an infidel based on their supposedly deviant words or deeds is generally perceived as objectionable in Sunnism, but many Sunni religious authorities have leaned in the direction of castigating those who engage in questionable practices, are insufficiently strenuous in their piety, or adopt “heretical” dogmas as being virtually or actually beyond the pale of what can be called Islam.38

Despite this, the willingness to explicitly and unambiguously mark fellow Muslims as outsiders is rather more conspicuous as a sectarian tendency; this is one of the most obvious ways in which ISIS moves away from what is traditionally considered the consensus positions of Sunnism and towards others more readily associated with groups that were historically at the fringes of mainstream Muslim society. It is important to emphasize here that the various communities of Zaydi, Isma’ili, and Twelver Shi’ah are today generally much more accommodating towards Sunnis in both their theology and their social practices. The Nizari Isma’ilis in particular have become well-known for their promotion of tolerance and a progressive ecumenism through the various philanthropic initiatives supported by their spiritual leader, HH The Aga Khan. However, many schools of Shi’ah originally espoused a militant ideology that rejected Sunnis – really anyone who failed to accept their claims – as heretics no better than infidels, thus deliberately taking up a counter-establishment position. This is a tendency that the Fatimids inherited from those earlier militant groups, which articulated doctrinal positions of radical anti-Sunnism as a politically expedient means of delegitimizing established regimes that marginalized and persecuted the Shi’ah. As we have noted, part of the militant posture of the Fatimid propaganda text is rejecting the Sunni position as illegitimate by using specific negative epithets for Sunnis, referring to them as idolaters, Pharaohs, and the “Jews of our community.” The use of code terms to mark insiders and outsiders is a mainstay of sectarian discourse more broadly, but the parallel with ISIS’ refusal to acknowledge its opponents as “Muslims,” terming them apostates, hypocrites, Ṣafawīs, and so forth, is particularly striking.39

Overall, the rationale behind the use of such language, whether in the tenth or the twenty-first century, is not difficult to discern. Extolling the virtues of one’s supporters as the true Muslims, those who are most closely aligned with the spirit of Muḥammad’s teachings and whose actions are cast as predetermined, the very fulfilment of prophecy, is an obvious method of legitimizing a clear minority position. Conversely, ‘othering’ one’s fellow Muslims as outsiders, no better than dhimmīs or infidels, has the effect of justifying their conquest, subordination, and, if they resist, their enslavement or annihilation, as if they were not Muslims at all. Calling the integrity of the Islam of one’s opponents into question and marking them as legitimate targets of violence gains particular urgency in an atmosphere saturated with apocalypticism, especially because the traditional prophecies explicitly assert that a state of civil war, fitnah, will inevitably precede the coming of the Mahdī. This is the exact reason why traditions on the terrible events of the End Times are labeled fitan (the plural of fitnah), after the extreme internecine struggles that will erupt within the community as harbingers of apocalypse.

Waiting for the flood: qurʾānic exegesis, prophetic history, and “intellectual terrorism”

The ISIS movement’s invocation of the Qurʾān, ḥadīth, and other classical sources of Islam in its propaganda has attracted significant attention since they first rose to international prominence with their capture of Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city, in the beginning of the summer of 2014. However, when we peruse Dabiq, the group’s English-language propaganda magazine, what we find is that their interpretation of the Qurʾān is typically implicit and allusive rather than overt and direct. An example of this is the extended use of a specific qurʾānic theme in an early issue of Dabiq, namely that of Noah’s Ark.

This theme is treated prominently in the second issue of Dabiq; its cover features a dramatic image of the Ark in a storm-tossed sea, with captions highlighting the two main features contained therein: “It’s Either the Islamic State or the Flood” and “The Flood of the Mubāhalah” (see Gallery Image E). Rather than engage in direct and systematic commentary on the Qur’an, the author of the first piece, one ‘Abū ʿAmr al-Kinānī,’ ruminates on the theme of Noah and the flood that destroyed his sinning people; his interpretation communicates a sophisticated message about the Islamic State and its various claims.40 As an example of sectarian, politically motivated exegesis, ISIS’ approach to the qurʾānic topos of the flood offers us yet another point of comparison with the Fatimids and other militant Shi’i movements, as it has much more in common with the taʾwīl exegesis practiced by Shi’i commentators on the Qurʾān than it does with classical Sunni tafsīr.

In the Qurʾān, the story of Noah is similar to that of the Bible in its overall contours: God warns Noah of the impending destruction that He will cause by submerging the earth beneath a great deluge; Noah is commanded to save his family by building an ark, to the ridicule of his contemporaries; subsequently, God’s foretold punishment for the sins of humanity is realized and all living beings except those ensconced safely on the Ark perish. The Bible describes all this in detail in Genesis 6–9, while these details are largely just presupposed in the qurʾānic versions of the narrative. However, the qurʾānic understanding of the narrative differs from that of the Bible in various ways as well. For one thing, in the Qurʾān there is very little description of the making of the Ark, the coming of the deluge, or the destruction it wreaks on the earth, as in Genesis. Instead, in keeping with the tendency to ‘flatten’ the biblical stories of the prophets into their most basic details and emphasize their most readily generalized elements, the qurʾānic versions of the story tend to place great emphasis on a theme that is entirely absent from the account in Genesis but resonates with the stories of other prophets found in the Qurʾān: Noah’s engagement with his wayward people to try to persuade them to repent and their obstinate rejection of his message.41

This element of the qurʾānic portrayal of the Noah story is significant because it is exactly the aspect of the story that ISIS emphasizes in this piece in Dabiq. The story is invoked in the context of a polemic against Muslims whom they dub the “proponents of choice” or simply “the pacifists.” These people claim that coercion is wrong, and that Muslims should not impose their views on others by force; all people should have the freedom to choose to believe or not to believe as they personally see fit. This is a traditional posture found among Sunnis and Shi’is alike, generally based on a reading of Q Baqarah 2:256, there is no coercion in religion, for truth has been clearly distinguished from falsehood.42 As ISIS spokesmen see it, however, the qurʾānic Noah story presents clear proof that this liberal ideal of free, unfettered choice in matters of faith is wrong, insofar as the story presents a clear opposition between salvation through cleaving to the truth and imminent destruction. The critical aspect of the exegesis of the story that is presented (or implied) here is that, in the view of ISIS’ spokeman, the coming of the flood cannot be construed as God’s punishment on the infidels of Noah’s time due to their disbelief, as is commonly presupposed. It is perhaps natural to think so; this is certainly the basic understanding of the story in the Bible, and the Qurʾān simply asserts that the unbelievers of Noah’s time were destroyed in the deluge and subsequently damned to perdition in the afterlife.43 The relationship between these two separate facts, which may readily be interpreted as different aspects of God’s punishment upon the disbelievers, is not typically perceived to be problematic.

However, ISIS’ spokesmen do see a logical problem here. The Qurʾān repeatedly asserts that the punishment exacted for kufr is damnation to Hellfire; so perishing in the flood cannot be a punishment for this sin per se. So what is it? We may admire the ingenuity of ISIS’ exegete here in discerning the answer, if only to recognize the adroit way that what he perceives as a theological problem in the narrative provides him with an expedient pretext for articulating a political doctrine important to ISIS. If those who deny God are doomed to Hellfire, the flood can only be read as an instrument of coercion, a threat of physical destruction that backs up Noah’s call to his people to repent. Essentially, Noah issues a harsh threat to his people, believe or else; come with me and be saved, otherwise drown and be damned. The threat is a legitimate means of coercion intended to pressure people to submit to Noah’s message; it is part of his characteristic “methodology.”44 ‘Abū ʿAmr’ even goes so far as to state that if someone were to have believed in Noah’s basic message of repentance, but claimed that he had no right to coerce people to follow him, that denial of his prerogative to resort to coercion in and of itself would constitute kufr.45

Strikingly, Noah’s approach or “methodology” is here openly characterized as “intellectual terrorism.” It was his intention to scare people into believing with the threat of imminent destruction: “He told them with full clarity, ‘It’s me or the Flood’”—the phrase that inspires the title of this feature in Dabiq (see Gallery Image F).46 Further drawing on the image of Noah’s Ark, ‘Abū ʿAmr’ emphasizes that only those who cleave to ISIS, associate with their movement, pledge obedience to their caliph, and follow their teachings can be saved: “in every time and place, those who are saved from the punishment are a small group, whereas the majority are destroyed.”47

ISIS’ use of this imagery to communicate a basic point from their political doctrine is particularly striking, because the image of Noah’s Ark is commonly employed in Shi’i tradition as a figure for their communitarian theology. There is a well-known prophetic ḥadīth that states that fitnah would come to flood the community, and the only way to salvation would be to follow the Ahl al-Bayt or “People of the House,” that is, the Prophet’s family.48 The Shi’ah have long interpreted this tradition to mean that only those who recognize and obey the imāms from the family of ʿAlī, the leaders recognized by their community, will find safe refuge from the worldly conflicts that will (or have) rent the Muslim ummah; they alone will survive the “flood” of fitnah and achieve both worldly and ultimate salvation. Noah’s Ark has thus been a favorite motif of Shi’i visual culture for many centuries (see Gallery Image G).49 It is a natural image for a path to salvation chosen by and available only to the very few.50 Given its recurring emphasis on the tiny minority that have always followed the prophets and imāms, it is unsurprising that our Fatimid text cites this tradition (see Gallery Image H):

اني لارى مواقع الفتن خلال بيوتكم كموقع القطر… فقال مثل أهل بيتي كمثل سفينة نوح من ركبها نجا ومن تخلف عنها غرق اي من سلك سبيلهم واستن بسنتهم لا يغرق بالفتن كقوم نوح

[The Prophet said:] “Truly, I see fitnah seeping into your homes like rainfall… But my House is like Noah’s Ark; the one who boards it is saved, and the one who spurns it is drowned. That is, the one who follows the path of my family and cleaves to it will not be drowned in fitnah like the people of Noah were drowned in water…”51

The invocation of this imagery of the Ark and the Flood in both Dabiq and the Fatimid text demonstrates in a vivid way that there are certain symbols and ideas that have historically had significant traction among Muslim groups that seek to utilize them for specific purposes. For ISIS, the Ark that saves from fitnah or communal strife (as well as serving, ultimately, as the sole vehicle for salvation) is not loyalty to the family of the Prophet, as in our Fatimid text, but rather, as seen here in Dabiq, immigrating to join ISIS to fight for the Islamic State under the banner of their caliph.52 For ISIS, as for the Fatimids, only that tiny minority that recognizes its claims and pledges obedience to them can be saved: to quote Dabiq again, “in every time and place, those who are saved from the punishment are a small group, whereas the majority are destroyed.” In a strikingly similar way to the militant Shi’ah who sought to gain support for their resistance to Sunni authorities over a thousand years ago, ISIS’ rhetorical goal is to valorize the path of an elite minority and to justify a posture of extreme militancy in support of their statebuilding project and their extreme political doctrines and claims.53

Calling down God’s curse: prophetic precedent and political intimidation

ISIS’ message is further distinguished by a unique exegetical flourish found here in Dabiq. As noted above, this is a special issue of Dabiq devoted to the theme of the Flood, with two separate pieces on this included therein: first “It’s either the Islamic State or the Flood,” the piece on Noah’s intellectual terrorism discussed above, and then a second item, a feature entitled “The Flood of the Mubāhalah.”54

Understanding the significance of this term mubāhalah requires some familiarity with the traditional account of early Islamic history. According to that traditional account, delegates from the Christian community of Najrān, the center of Arabian Christianity in the Prophet Muḥammad’s day, once came to see him and disputed with him over theological questions pertaining to the nature of Jesus (see Gallery Image I). In response, God revealed the qurʾānic verse which is now Q Āl ʿImrān 3:61:

If anyone disputes with you about this now, after knowledge of the matter has come to you, Say: ‘Let us get together, our sons and your sons, our daughters and your daughters, us and you, and let us earnestly pray, and invoke the curse of God on those who lie.’

The phrase “let us invoke the curse” renders Arabic nabtahil, from the verb ibtahala; if two parties do this in opposition to one another, the appropriate verbal form is tabāhala, from which the noun mubāhalah, a mutual imprecation, derives. Muḥammad received this verse from God, brought the members of his family together, and then faced off against the Christians, who backed down because they were intimidated, too frightened to call down God’s wrath as warrant for the claims they made about Jesus. Ever after, this event has been called the mubāhalah.55

This episode from the Sīrah is very important for Shi’ah, who understand it to establish a significant role for Muḥammad’s family as witnesses to and warrants for divine truth. While the Christians of Najrān gathered learned adult men as their witnesses, Muḥammad is sometimes described as coming to the assembly with only four people accompanying him: ʿAlī, Fāṭimah, and their sons Ḥasan and Ḥusayn. This is one of a handful of events that seems to establish that Muḥammad’s close relatives possessed a special authority and knowledge based on their intimate relationship with him; the Prophet’s bringing them (and only them) to the confrontation implies an elevated status for these individuals above all others, even a kind of partnership.56 Shi’i sources, including our Fatimid text, thus make much of this tradition, as it seems to establish the special authority of the imāms of the Ahl al-Bayt.57

For ISIS, this episode is important for a different reason. Astonishingly, the ISIS leadership has actually done this. Originally entering the Syrian conflict in 2011 as ISIS’ proxy, the insurgent group most commonly called Jabhat al-Nuṣrah quickly came to differ with the leaders of the Islamic State over both strategy and tactics; by 2013 Jabhat al-Nuṣrah had split from ISIS and the two groups commenced excoriating each other in social media.58 In early 2014 the leadership of Jabhat al-Nuṣrah began openly denouncing the ISIS leadership as Khārijites, invoking the name of this notorious sect from early Islamic history to imply that ISIS had left the Sunni fold due to its members’ extremism and open acts of violence against other Muslims. 59 In response, ISIS spokesman Abū Muḥammad al-ʿAdnānī invited the leadership of Jabhat al-Nuṣrah (whom they derogatorily refer to as Jabhat al-Jawlānī, after Abū Muḥammad al-Jawlānī, the head of the organization) to a public dispute and a mubāhalah to settle their grievances.

Here in Dabiq, the rationale and legitimacy of this action is explained in a few pages in a piece entitled “The Flood of Mubāhalah.” Intriguingly, the circumstances under which ISIS initiated this action receive less attention than the lengthy explanation of historical precedents for it. In particular, the author notes that Muḥammad never asserted that only his summoning of God’s curse against the Christians of Najrān was legitimate. Rather, various authorities are cited supporting the permissibility of the practice in the time after Muḥammad, and a number of examples of scholars invoking God’s curse in a mubāhalah against their rivals in legal and doctrinal disputes are supplied.60

Why the mubāhalah against Jabhat al-Nuṣrah is to be likened to a flood is not noted here; nor is the connection to the flood of Noah’s time explicitly parsed. However, we can infer, in light of the preceding piece “It’s Either the Islamic State or the Flood,” that a connection to Noah’s preaching to his people, specifically his threatening them with destruction as “intellectual terrorism,” is implied. This is exactly what the ISIS leadership believes Muḥammad was doing with the mubāhalah, essentially intimidating the Christians of Najrān into acquiescing to his claims and abandoning their own, since he knew he was right and they were wrong, and God would intervene directly to vindicate him. Further, this is what ISIS spokesmen see themselves as doing: committing intellectual terrorism against doctrinal rivals—or actual violence against people who will not submit to them—as a legitimate means of coercing submission and acquiescence to their claims. They believe themselves to be in the right so strongly that they are willing to invoke God’s curse on any who gainsay them. Moreover, since there is a well-known prophetic precedent for this behavior, ISIS immediately gains the rhetorical advantage of being able to claim to be following in the footsteps not only of various Salafi icons like Ibn Taymiyyah and Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhāb, but obviously of the Prophet himself.61 This is but one of many examples of ways in which ISIS and its supporters deliberately blur the distinction between past and present and hearken back to the golden age of Islam’s founding that they idealize.62

Valorizing violence at the end of days

The striking commonalities between Fatimid and ISIS propaganda—in particular the conjunction between violence, coercion, and promised retribution against those who deny their authority or defy their claims—are arguably due to the necessity for both movements to justify their revolutionary statebuilding projects in their respective historical and political contexts. The Fatimids came to power in the tenth century by overthrowing various governments and principalities in North Africa that drew their legitimacy from either token or actual loyalty to the reigning Abbasid caliph in Baghdad, forging a new caliphate through the use of force backed up by alternative religious justifications. ISIS has quite evidently done exactly the same thing against the background of the nation-state system that has prevailed in the Middle East since the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. Both groups rely on themes familiar from Islamic history, or topoi like Noah’s Ark drawn from the Qurʾān and tradition, to drive a particular point home to their audience: a terrible reckoning is coming, and only the in-group—whether ISIS or the Fatimids—will be saved, along with those that not only accept their doctrines but acquiesce to their political authority.

Both movements not only project a message grounded in millenarian eschatology but use their millenarianism as a justification for violence. This is true of many movements that espouse an apocalyptic or chiliastic ideology. Not only does the claim that ISIS is fulfilling prophecy serve to legitimize their authority, but the idea that a terrible apocalyptic reckoning is coming inspires loyalty among their supporters, and infuses their communications with a sense of urgency that facilitates the transgression of boundaries and the violation of social norms.63 We can recall again their blunt statement “it’s us or the Flood”: compounding the psychological effects of the radical dislocation of recruits, commission of extreme acts to cement allegiance to the group, imposing severe penalties for desertion, and so forth, the projection of a sense of impending danger and imminent cataclysm—a mentality, essentially, of apocalyptic emergency—further serves as an instrument to subvert and overthrow the behavioral and cognitive norms of recruits’ home communities and of Muslim society at large. Foremost here is the need to foster and justify open hostility against other Muslims, a species of violence that most forms of historical Islam repudiate—and one that seems unjustifiable on the basis of the Qurʾān, one might add.

On the other hand, given the strong sectarian impulse that characterized some of the more militant schools of Shi’ah in early and medieval Islam, these groups were more comfortable ‘othering’ Muslims who rejected the cause of ʿAlī and his family as unbelievers. For its part, the Fatimid propaganda text refers to such rejecters and the regimes that they putatively support as idolaters, hypocrites, and apostates—all terms that associate Sunnis with categories of people whom the Qurʾān and Islamic tradition generally identify not only as enemies of the faith but as legitimate targets of violence. One appellation for Sunnis in the text is especially noteworthy, namely “the calf worshippers of our community.” In one exceptional passage, the text uses the figure of the Israelites’ idolatrous worship of the Golden Calf as a metaphor for those whose loyalties are misplaced, following imāms who have abandoned the cause of the Ahl al-Bayt instead of supporting them.

The qurʾānic as well as the biblical accounts of the Calf episode depict the death of those who went astray worshipping it, albeit in different ways. In Exodus 32:25-29, Moses rallies the tribe of the Levites to go through the camp and pacify the idolaters in a mass bloodletting. In the Qurʾān, the Israelites seem to collectively recognize their guilt, and Moses commands them to kill themselves to make things right with God. The verse depicting this in Sūrat al-Baqarah has been interpreted in different ways, though the dominant strand in early exegesis at least was that the key phrase, fa’qtulū anfuskakum (literally “kill yourselves”), means “kill each other,” and so Moses was enjoining the Israelites to engage in open combat, in which the innocent would overcome and slay the guilty.64

Evoking this image of the righteous Israelites purging the community of idolaters in one of its most transparently chiliastic passages, our Fatimid text proclaims that while repentance may formerly have been an option for those who did not cleave to the correct imāms, now with the coming of the Mahdī, the “gates of repentance” are shut tight for the “calf worshippers” (see Gallery Image J):

لكن امة النبي صلى الله عليه واله قبل خروج المهدي عليه السلم دون القتل فاذا جرج خليفة المهديُ غُلِّقَت ابواب التوبة عن عبدة العجل من امتنا كما تغلق عن جميع مَنْ لم يومن قبل طلوع الشمس من المغرب

While in the time before the emergence of the Mahdī, the community of the Prophet had to forego killing, when the caliph al-Mahdī emerged, the gates of repentance were shut tight for the Calf worshippers from this community—just as they were shut tight for all those who did not believe before the rising of the sun in the west…65

The Fatimid text’s reference to the slaughter of the Calf worshippers exploits this qurʾānic portrayal of the purging of a sinning, deviant portion of the prophetic community by those who follow the path of its true leaders, dutifully rejecting the temptation to turn aside and cleave to false idols instead. The sinister implication is that such a bloodletting is imminent for the Calf worshippers of the present day, those who reject the imāms of the family of ʿAlī and follow idolatrous leaders instead, now that “the rising of the sun in the west” (the advent of the Mahdī) has taken place.

It is worth noting that Sunni exegetes have been extremely reluctant to read the Sūrah 2 story in such a way. Although early exegetes recognized the qurʾānic injunction to “slay yourselves” as Moses’ command to his loyal followers to purge the idolaters from the community, already by the tenth century, Sunni exegetes appear to have disliked the sectarian implications of this interpretation, and focused instead on readings that saw the killing as a collective atonement—the whole community being punished for the crime of the Calf, guilty and innocent alike—or even insisted that the ‘killing’ referred to in Q 2:54 is figurative.66 But for a sectarian movement like the Fatimids, the story is naturally read as advocating a violent purge of deviant transgressors from the community.

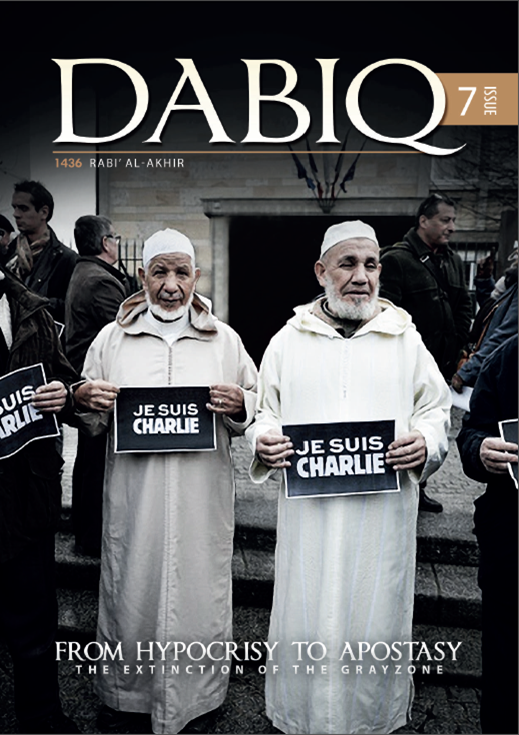

As for the Fatimids, so too for ISIS: apocalypticism justifies and encourages radical acts of violence, enabling the remaking of society, the redrawing of boundaries, and redefinition of the entire ethos of the community. With the apocalyptic final struggle impending, the division between sinners and saved becomes an all-encompassing concern; there is no in-between. Thus, a more recent issue of Dabiq, released in the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo attacks in Paris, castigates Muslims who apologized for the killings or expressed solidarity with the victims (see Gallery Image K). This is discussed under the rubric “Extinction of the Grayzone.” The “grayzone” is exactly what it sounds like—that intermediate area where ISIS locates Muslims who are not in solidarity with them but rather criticize them and thus side with unbelievers—making them, essentially, infidels although they may purport to be Muslims.67

Those dwelling in the grayzone are, in the eyes of ISIS’ spokesmen, apostates, hypocrites, infidels, and so forth, and so unambiguously merit death for their hypocrisy and disbelief. This “gray movement,” the Islam of the “grayish,” has existed since the time of the Prophet, but must be eliminated because Islam in their view is intrinsically about drawing a sharp distinction between truth and falsehood, with no room in the middle.68 ISIS’ position here confirms the idea that millenarianism, especially millenarian violence, aims to remake the world as it is into something radically new. This becomes abundantly clear when we recognize the reconfiguration of society, the undoing of assimilation and liberalism and diversity, that ISIS aims to achieve in the countdown to the Hour, the clock having started with their proclamation of Abū Bakr al-Baghdādī’s election by the Islamic State Shura Council in May 2010 and his assumption of the caliphal title amīr al-muʾminīn or Commander of the Faithful, supposedly in fulfillment of ancient prophecy.69

Conclusion

As with the militant Shi’i groups of early and medieval Islam, so too with ISIS: notions of a saved minority and a sinning majority; an absolute distinction between the upright and the errant, the damned and the saved, with no room for a “grayzone” in between; and an imminent judgment that will destroy the moderates and their false leaders, ushering in a new era—all of these themes, alongside an embrace of truly spectacular violence, the fostering of a state of ultrafitnah, a war of all against all in the Muslim community—all of these serve to support the creation of a new state, grounded in arguments based on the traditional sources of Qurʾān and ḥadīth read through a conspicuously sectarian lens, in the service of a new, militant, perfectionist order that eagerly anticipates the coming of the apocalypse.70

To reiterate a point we made earlier, the ideology of ISIS is not crypto-Shi’ism. The purpose of this comparative exercise has not been to assert some direct line of influence from the Fatimids to their movement, or imply that ISIS is a Sunni recurrence of the militant Shi’ism that troubled the political, social, and religious order of the dār al-Islām a thousand years ago. The reduction of all varieties of radicalism to a single essence is clearly historically problematic. This reductionism has recently been manifest in ill-considered attempts to compare ISIS to the ‘Assassins,’ the aforementioned Nizari Isma’ili sect that conducted guerilla warfare (including targeted political killings, thus giving a name to this phenomenon that persists today) against Sunni authorities in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Happily, these careless comparisons have been energetically and thoughtfully refuted quite publicly, particularly by Farhad Daftary, perhaps the preeminent living scholar of the Isma’ili tradition.71 To align ISIS and the Nizaris based solely on a stereotyped conception of ‘Islamic terrorism’ does a clear disservice to the complexities of the historical realities involved. While it is debatable whether ISIS merits anything but the most strident condemnation, the Nizaris at least have tended to be misapprehended and caricatured by Western observers since the Middle Ages.

At the same time, as our treatment here has hopefully shown, careful examination of the textual evidence points to specific points of similarity between the rhetoric employed by the Fatimids and ISIS as examples of a recurring tendency within historical Muslim communities that incline toward extreme sectarianism—that is, the resemblance is structural, possibly (for lack of a better word) sociological. Some of the parallels are admittedly deep-rooted and likely stem from centuries-old historical interactions and processes of symbiosis between Sunnis and Shi’ah. For example, the Sunni prophecy of twelve righteous caliphs who will rule in the age before the coming of the Mahdī (with ISIS claiming that Abū Bakr al-Baghdādī is the first of them) is clearly an appropriation of the Shi’i tradition of enumerating twelve Alid imāms. Other parallels are clearly due to the common vocabulary and images found in fitan traditions in Islam, upon which both Sunnis and Shi’ah alike draw; thus, ISIS propaganda sometimes asserts that “the sun of jihad” has risen; the similarity to the Fatimid invocation of the image of “the rising of the sun in the west” to describe the establishment of their dominion in the Maghrib may be due to the popularity of the ṭulūʿ al-shams prophecy in fitan sources, though it is also possibly due to simple coincidence.72

Moreover, at least some of the resemblances between ISIS’ rhetoric and claims and those we more readily associate with militant Shi’ism might be attributed to the diffuse influence of certain currents in contemporary Twelver Shi’ism in the Iraqi milieu. They may even be attributable to the personal background and experience of ISIS personnel. For example, as McCants notes, Abū Bakr al-Baghdādī grew up in a lower middle-class family in Samarra, “steeped in the mythology and ideas of Twelver Shi’ism”; he has even claimed descent from the Tenth Imām, ʿAlī al-Hādī.73 Given the pervasive presence of Twelver Shi’ism in contemporary Iraq, for Iraqi Sunnis, opposition to Shi’ah by no means precludes acculturation to Shi’i ideas and traditions. More generally, the distinctive fusion of millenarianism and insurgency that has given ISIS its bellicose bite could readily have been communicated from Shi’i militias and preachers, through propaganda, sermons, and the like, to Zarqawī, Abū Bakr al-Baghdādī, and other AQI and ISIS operatives and ideologues.74 Overall, the discursive parallelisms between Sunni and Shi’i groups has often been most acute when communities live in close proximity to one another or have even been socially integrated to some degree, as has often been the case in Iraq’s history.

However, all that said, our main goal here has been to show that minority and marginal sectarian formations in Islam have often relied on particular types of rhetoric, a symbolic language characteristic of sectarianism, in order to justify their positions. This is especially true of any Muslim group that seeks to articulate a religiously grounded argument sanctioning violence against their fellow Muslims. A logical fallacy commonly found in media discussions of Islam is the tendency to absolutize it as essentially violent or essentially peaceful; not only are religions as abstract concepts incapable of being violent or peaceable, but even when we speak of Muslims as individuals and communities possessing full human agency, to attempt to characterize all Muslims as having one or another personal quality, political orientation, or moral disposition is of course ludicrous. Rather, as is the case with all religions, the textual and traditional sources of Islam offer rich resources for believers to articulate diverse positions. Some of those positions have been more typical and deemed normative by consensus than others, to be sure; and judged by the standard established by both historical and majoritarian forms of Islam, there is no question that both the early Fatimids and ISIS—as extreme sectarian formations—are aberrant. Nevertheless, we must recognize that the tradition does provide a symbolic language to those who seek a pretext for tightening the definition of who the real members of the community are and fostering violence against those within the community who disagree.75 The coincidences in symbols, rhetoric, and ideology between the Fatimids and ISIS we have discussed here clearly demonstrate this.

About the author

Michael Pregill (B.A. Columbia University, 1993; M.T.S. Harvard Divinity School, 1997; Ph.D. Columbia University, 2007) is Interlocutor in the Institute for the Study of Muslim Societies and Civilizations at Boston University and coordinator of the Mizan digital scholarship initiative. His primary area of expertise is early Islam, with a specific focus on the Qurʾān and its interpretive tradition (tafsīr). Much of his research concerns the reception and interpretation of biblical, Jewish, and Christian themes and motifs in tafsīr and other branches of classical Islamic literature; critical approaches to Islamic origins; and the perception and representation of Jews and Christians in Islamic culture.

Notes

All digital content cited in this article was accessed on or before September 21, 2016.

[1] In preparing this article for publication, I have profited considerably from the comments of Ken Garden, Will McCants, and Stephen Shoemaker, as well as from Ken’s generosity in responding to the original paper on which this article is based both publicly and now in writing as well. I also thank the anonymous peer reviewers for their helpful suggestions.

A number of very thorough scholarly and journalistic investigations of the ISIS phenomenon have been published to date. Here, I will refer frequently to Jessica Stern and J. M. Berger, ISIS: The State of Terror (New York: Ecco, 2015) and William McCants, The ISIS Apocalypse: The History, Strategy, and Doomsday Vision of the Islamic State (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2015).

[2] Islamist insurgencies have of course managed to overthrow regimes and seize power before. Further, in the case of Iran, an Islamist faction co-opted a popular revolution and founded a theocratic state with significant investment in sponsoring terrorism. But in the case of ISIS, the insurgent movement became the regime controlling a new territorial state carved out of portions of older states in decline, imposing itself on the citizens of the territories it has come to control without significant participation or support from the majority of them.

[3] On ISIS’ declaration of the caliphate of Abū Bakr al-Baghdādī, see Richard Bulliet, “It’s Good to Be the Caliph,” Politico, July 7, 2014 and Malise Ruthven, “Lure of the Caliphate,” New York Review of Books, February 28, 2015.

[4] On the legacy of Sykes-Picot and the problematics of the modern nation-state system in the Middle East, see Yezid Sayigh, “Reconstructed Reality,” Qantara.de, March 21, 2016.

[5] The Jazīra has been politically unified in the past, under both pre-Islamic and Islamic regimes, and arguably, attempts to dismember it are innately unstable, while economic and strategic advantage accrues to regimes that manage to unify it. Khodadad Rezakhani has conjectured that the Sasanians’ loss of control over its western, Mesopotamian territory in the wake of the Arab invasions was due primarily to the regime’s inability to exploit this region’s economic potential, which was fully realized with its reunification under Islamic rule: see “The Arab Conquests and Sasanian Iran (Part 2): Islam in a Sasanian Context” (https://mizanproject.wpengine.com/the-arab-conquests-and-sasanian-iran-part-2/). The Jazīra was the heartland of the Zengid emirate based in Mosul; significantly, the Zengids were one of the Muslim powers that battled and contributed to the eventual defeat of the Latin Crusader states. Abū Muṣʿab al-Zarqawī, head of Al-Qa’idah in Iraq (AQI) who led brutal terror campaigns there from 2004 to 2006 and has been seen as one of the founders of ISIS, idolized Nūr al-Dīn Zengī, the founder of the emirate (McCants, The ISIS Apocalypse, 8–9).

[6] One of the most notorious examples of ISIS’ willingness to openly engage in extreme acts of brutality was the January 2015 execution of captured Jordanian pilot Muʿath al-Kasasbeh by burning; although it was widely denounced as un-Islamic, as Andrew Marsham has recently shown, there are significant pre-modern precedents for this form of execution by Muslim authorities, particularly in the early caliphal period, at which time it was occasionally used as a mode of execution for rebels in particular (“Attitudes to the Use of Fire in Executions in Late Antiquity and Early Islam: The Burning of Heretics and Rebels in Late Umayyad Iraq,” in Robert Gleave and István Kristó-Nagy, Violence in Islamic Thought from the Qurʾān to the Mongols (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015), 106–127).

[7] For a survey of classical traditions, see David Cook, Studies in Muslim Apocalyptic (Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam 21; Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 2002) and for the contemporary revival of apocalyptic anxieties and enthusiasms, see David Cook, Contemporary Muslim Apocalyptic Literature (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2005) and Jean-Pierre Filiu, L’Apocalypse dans Islam (Paris: Fayard, 2008), published in English as Apocalypse in Islam (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011). Scholars have generally been slow to recognize the significance of apocalypticism in contemporary jihadist movements despite the work of Cook and Filiu; in his 2011 review of the English translation of Filiu’s book, Charles Cameron presciently warned that scholars and policymakers needed to take the rising tide of apocalyptic enthusiasm in the jihadist fringe seriously (“Hitting the Blind-Spot: A Review of Jean-Pierre Filiu’s Apocalypse in Islam,” Jihadology, January 24, 2011).

[8] A reliable reconstruction of early Fatimid history has proven elusive. The background of the movement is intrinsically obscure because of its origins as a clandestine organization; even the genealogy of ʿAbd Allāh al-Mahdī and other early Fatimid caliph-imāms remains conjectural because the dynasty’s spokesmen represented their links to earlier imāms such as Muḥammad b. Ismāʿīl (d. 813) differently at different times. For recent accounts, see Michael Brett, The Rise of the Fatimids: The World of the Mediterranean & the Middle East in the Tenth Century C.E. (Leiden: Brill, 2001); Farhad Daftary, The Ismāʿīlīs: Their History and Doctrines (2nd ed.; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 126 ff.; and Paul Walker, “The Ismāʿīlī Daʿwa and the Fāṭimid Caliphate,” in Carl F. Petry (ed.), The Cambridge History of Egypt, Vol. I: Islamic Egypt, 640–1517 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 120–150. The late tenth-century account of al-Qāḍī al-Nuʿmān, Iftitāḥ al-daʿwah, is available in English translation in Hamid Haji (trans.), Founding the Fatimid State: The Rise of an Early Islamic Empire (The Institute of Ismaili Studies Ismaili Texts and Translations Series 6; London: I. B. Tauris, 2006).

[9] Such millenarian claims were not unusual in themselves; it is widely recognized that the Abbasids had made similar claims in their campaign to overthrow the Umayyads. See the classic treatment of Moshe Sharon, Black Banners from the East. The Establishment of the ʿAbbāsid State: Incubation of a Revolt (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1983) and the more recent work of Hayrettin Yücesoy, Messianic Beliefs and Imperial Politics in Medieval Islam: The ʿAbbāsid Caliphate in the Ninth Century (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2009). Similarly, another branch of the Ismāʿīlīs, the Nizaris of Alamut, pursued a parallel trajectory when their imām proclaimed the qiyāmah or resurrection as a new age of realized eschatology in which the faithful lived in a redeemed state free of the constraints of shari’ah. On this, see the classic treatment of Marshall G. S. Hodgson, The Order of Assassins: The Struggle of the Early Nizārī Ismāʿīlīs Against the Islamic World (The Hague: Mouton, 1955; repr. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005), and now Jamel A. Velji, An Apocalyptic History of the Early Fatimid Empire (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016), 109–122. The latter emphasizes the continuity of Nizari ideas with those of the Fatimids two centuries previous; understood in its proper context, the realized eschatology of the movement at Alamut no longer appears like an aberrant indulgence of antinomian enthusiasm. Arguably, these later irruptions of apocalyptic fervor draw on and revive a political eschatology already dominant in the Qurʾān and the prophetic period, which was itself characteristic of the late antique environment in which Islam was revealed: see Stephen J. Shoemaker, “‘The Reign of God Has Come’: Eschatology and Empire in Late Antiquity and Early Islam,” Arabica 61 (2014): 514–558.

[10] Along with “the Day” (al-yawm), “the Hour” (al-sāʿah) is the most common qurʾānic term for the cataclysmic end of time and advent of the Final Judgment.

[11] On this manuscript, see Michael Pregill, “Measure for Measure: Prophetic History, Qur’anic Exegesis, and Anti-Sunnī Polemic in a Fāṭimid Propaganda Work (BL Or. 8419),” Journal of Qur’anic Studies 16 (2014): 20–57.

[12] For a concise account of Fatimid literary production in the context of the daʿwah, see the now-classic account of Heinz Halm, The Fatimids and their Traditions of Learning (London: I. B. Tauris in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, 1997).

[13] See the definitive discussion of this in Uri Rubin, Between Bible and Qurʾān: The Children of Israel and the Islamic Self-Image (Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam 17; Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1999), 168–189.

[14] BL Or. 8419, 2a–b. This tradition is sometimes called the ḥadīth of juḥr ḍabb on account of the unusual image of the lizard hole it evokes here. All translations from the Arabic are the author’s unless otherwise noted.

[15] Ibid., 1b. On the so-called firāq tradition, see Rubin, Between Bible and Qurʾān, 117–146.

[16] The Sunni polemical claim linking the Shi’ah and the Jews is at least partially historically rooted in an ancient inclination towards ‘biblicizing’ among the Shi’ah themselves, but took on a life of its own in heresiographical literature. See Steven M. Wasserstrom, “‘The Šīʿīs are the Jews of our Community’: An Interreligious Comparison within Sunnī Thought,” in Ilai Alon, Ithamar Gruenwald, and Itamar Singer (eds.), Concepts of the Other in Near Eastern Religions (Israel Oriental Studies XIV; Leiden: Brill, 1994), 297–324.

[17] For other Shi’i applications of this tradition, see Rubin, Between Bible and Qurʾān, 186–189. The tradition may very well have originated in anti-Shi’i polemic but was readily reoriented by Shi’i traditionists and authors in order to turn the tables on Sunnis.

[18] BL Or. 8419, 50b–51a. The perception of an analogy between the harsh treatment meted out to the Israelites by the Egyptians and that to which the Ahl al-Bayt were subjected was no doubt encouraged by Q Qaṣaṣ 28:3–4, which refers to Pharaoh’s making the people of the land into a party—a shīʿah—so as to weaken or oppress some of them.

[19] Ibid., 79b.

[20] On taʾwīl, see the classic discussion of Ismail K. Poonawala, “Ismāʿīlī Taʾwīl of the Qurʾān,” in Andrew Rippin (ed.), Approaches to the History of the Interpretation of the Qurʾān (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988), 199–222. To this should be added the new treatments of David Hollenberg, Beyond the Quran: Early Ismaʿili Taʾwil and the Secrets of the Prophets (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2016, forthcoming) and Velji, Apocalyptic History, 14–21. I am very grateful to both Prof. Hollenberg and Prof. Velji for generously sharing their much-anticipated work with me prior to final publication.