PDF

Download

Citations

Click and drag then release to select a passage to cite.

Annotations

How to submit annotations to Mizan Journal articles:

your work is published.

Search within

The Long Shadow of Sasanian Christianity

The Limits of Iraqi Islamization in the Abbasid Period

Image

Audio

Video

Chart or Graph

The Long Shadow of Sasanian Christianity

The Limits of Iraqi Islamization in the Abbasid Period

Introduction

Nothing about al-Wāsiṭ was original. As an Arab Muslim city in southern Iraq, founded by the Umayyad governor al-Ḥajjāj, it had been preceded two generations earlier by Kufa and Basra.1 It was not even the first city on its stretch of the Tigris, but was founded across the river from the still very lively Sasanian settlement of Kashkar (in Arabic, Kaskar).2 This earlier city continued to be an important Christian center into the late Abbasid period; its bishop administered the Iraqi churches during vacancies in the office of catholicos, the highest-ranking church leader in Iraq.3 Yet in the fourth/tenth century, the geographers Ibn Ḥawqal (d. after 362/973) and al-Muqaddasī (d. after 380/990) no longer remembered the existence of the pre-Islamic city; instead they described al-Wāsiṭ as a city founded by Muslims, occupying both banks of the river.4 The new Arab Muslim city had not only engulfed its predecessor town, but had also erased the memory of an important Christian center. The question facing scholars is how this happened, not just at al-Wāsiṭ but across Iraq, and also how quickly and thoroughly this transformation occurred.

Richard Bulliet’s 1979 book, Conversion to Islam in the Medieval Period, claimed only to be a tentative “essay,” and yet the field has largely taken it as the final word on the demographic process of Islamization in Iraq, as in most of the Middle East.5 While earlier scholars had proposed that mass conversion to Islam was a phenomenon of the Umayyad period, Bulliet proposed a slower chronology. Bulliet suggested that Muslims came to outnumber non-Muslims in Iraq only in the 270s/880s, much later than previous scholarship had thought, and that Muslims approached 90 percent of the population only at the end of the fourth/tenth century.6 The details of his argument need not occupy us here; despite some criticisms, this has become the standard chronology of Islamization in Iraq.

Further, Michael Morony proposed that by the third/ninth century, Muslims had probably become a “virtual majority” of Iraq’s population, and that the process of mass conversion may have paralleled the earlier sectarian competition for converts among “Nestorian” and “Monophysite” Christians.7 Unlike Bulliet’s concept of “social conversion,” namely that changing religion was as much or more about moving social groups as it was about dogma, Morony argued that conversion was fastest as a result of social dislocation, rather than as a cause for it, and that, conversely, the ability of certain groups to preserve earlier identities “did not depend on regional predominance but on cultural or social density.”8 Morony briefly references the conversion to Islam of Christian Arab nomads.9 In an agrarian region such as Mesopotamia, however, the rural sedentary population was necessarily much larger than the nomadic sector, and Morony does not discuss the progress of Islamization among the farmers. Instead, the conversions which he does discuss are those of Zoroastrians, not to Islam, but to Christianity.10 Counterintuitive though it may seem, it is even possible that the Christian population of Iraq was rising during the early Islamic period as a result of Zoroastrianism’s loss of state sponsorship.

More recent scholarship discussing conversion to Islam in Iraq addresses interreligious dialogue and polemics, as well as conversion narratives.11 Wadi Haddad has examined a few third-/ninth-century apologetic texts, particularly the correspondence between ʿAbd Allāh b. Ismāʿīl al-Hāshimī and ʿAbd al-Masīḥ b. Isḥāq al-Kindī, as well as ʿAlī b. Rabbān al-Ṭabarī’s (d. third/ninth century) defense of Islam, to demonstrate some of the different strategies used to make conversion to Islam appealing or unappealing.12 Giovanna Calasso has discussed accounts of conversion, devotional zeal, and religious instruction in a Basran biographical collection of the third/ninth century.13 Sidney Griffith has argued that during the first centuries of Muslim rule, in the social context of increasing Christian conversion to Islam, clergy writing in Syriac and Arabic used Islamic cultural categories to construct their denominationally distinct identities.14 David Bertaina has explored the shifting uses of interreligious dialogue texts from the pre-Islamic period to the early second millennium CE, by Christians and Muslims, in Iraq and more broadly.15 These scholars all contextualize their documents in Bulliet’s timeline for a “wave of conversions” in third-/ninth-century Iraq, and ascribe to Christian authors the goal of “stemming the tide of conversion.”16 Likewise, Michael Penn approaches conversion on the basis of narrative Syriac sources, but he questions the rapidity of Bulliet’s timeline and counters that into the mid-third/late-ninth century, “the actual number of converts from Christianity to Islam did not threaten the survival of Syriac Christianity”; nevertheless, he also suggests that “the threat of mass conversion weighed heavily on the minds of Syriac authors” during the early Islamic period.17 All such texts are elite productions, relevant only to the small portion of the population which was literate, and therefore this scholarship does not revise our understanding of the pace of non-elite Islamization.

In 2005, Bulliet explored whether dynamics of geographical diffusion might add nuance to the model of innovation diffusion through social contact which he proposed in 1979.18 His use of spatial diffusion was limited in this work, primarily serving to link a progress of conversion with shifting onomastic patterns observed in a fourth-/tenth-century biographical dictionary. He concluded that for Iran, the object of his 2005 chapter, the chronology which he had proposed in 1979 was biased in favor of urban centers, and needed to be revised as much as a century later in order to account for slower rural adoption of Islam.19 The urban and rural sectors of Iraq’s population were divided as sharply as Iran’s, so Bulliet’s proposed timeline for the Islamization of Iraq might likewise be revised later in order to account for the urban bias of his study.

The present article considers what geographical texts might tell us about the diffusion of Islam in Iraq. As Zayde Antrim has indicated, a diverse Arabic “discourse of place” developed in the early medieval period, representing not a unified genre but a shared set of assumptions about place and space.20 This discourse included books of “historical geography” (such as Kitāb Futūḥ al-buldān by Aḥmad b. Yaḥyā b. Jābir al-Balādhurī [d. ca. 279/892]), works of the Balkhī school of mapmaking (such as Kitāb Ṣūrat al-arḍ by Abū’l-Qāsim b. ʿAlī al-Naṣībī Ibn Ḥawqal and Aḥsan al-taqāsīm fī maʿrifat al-aqālīm by Shams al-Dīn Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad b. Aḥmad b. Abī Bakr al-Bannāʾ al-Shāmī al-Muqaddasī), and other genres. The Kitāb al-Diyārāt of Abū’l-Ḥasan ʿAlī b. Muḥammad al-Shābushtī (d. 388/998) likewise organizes descriptions of monasteries into geographical regions. Another form of geographical thinking is displayed in lists of Christian dioceses compiled in Syriac and Arabic, reflecting the spatial diffusion of ecclesiastical infrastructure and hierarchies of precedence. Due to the literary nature of all these texts, composed in idiosyncratic ways for individual purposes, I have not attempted a numerical or computational analysis of these sources, such as might yield spuriously precise demographic figures.21 Instead, I have engaged in close readings of relevant passages, with attention paid to each author’s stated goals, rhetorical strategies, and unstated assumptions.

Exploring religious diversity through geographical texts both enables and requires us to consider Islamization as a multifaceted and multidimensional social and cultural transformation, involving more than simply the shifting numbers of people identifying as one religion or another. Geographical texts, like other extant literary works composed by premodern Muslim elites, do not contain demographic data in a form that modern scholars can usefully quantify.22 Religious adherence in the medieval Middle East also took different forms than it does today, and the dynamics of changing identification from one religion to another could look very different for different people or groups. These dynamics are an active area of research, but the language of “conversion” often presumes a modern Protestant model of religious identity and change that is of dubious applicability to the premodern Middle East.23 Therefore, due to the limits of our textual sources and the theoretical implications, this article avoids the language of “conversion.” Instead, what the texts do give us are statements about changing patterns of urbanization, the nature of land claims, the presence of infrastructure and architecture for religious rituals, and the shape of the ecclesiastical hierarchy. While these details cannot be used to reliably estimate populations, they do provide a broader picture of the changing place of non-Muslims in what scholars call “Islamic” society, as experienced and recorded by their contemporaries.

Scope and terminology

Both medieval Muslim authors and modern historians have found the plethora of flavors of non-Muslim religion distinctly confusing. While dividing the world into Jews, Christians, and Zoroastrians was clear enough, the internal diversity among Jews and Christians has typically held little interest, and much opportunity for misunderstanding, for medieval Muslims and modern Islamicists alike. The potential for confusion is exacerbated by the fact that though there were several different Christian denominations, each one referred to itself primarily as Christian and as orthodox, terms which were therefore useless for distinguishing one from another. To deal with this issue, when medieval Muslims needed to distinguish one denomination from others, they resorted to derogatory polemical labels coined by Christians themselves in the heat of intra-Christian theological controversies, and thus referred to Jacobites, Nestorians, and Melkites. In this they have been followed, largely unquestioningly, by modern Islamicists.

While certain Middle Eastern Christian authors in specific periods have been willing to own such labels, they retain their offensive sting for most people so described, and are as misleading as most insults. Thus, here I will refer to the so-called “Nestorians,” headquartered in Iraq, as the Church of the East or as Eastern Syriac Christians, due to their use of Syriac as their liturgical language and their location as the furthest east of the ancient churches.24 So-called “Jacobites” are customarily labeled by Syriacists, for lack of better options, either as Syriac Orthodox or Western Syriac Christians, although both labels may be challenged. Finally, while Syriac scholars as well as Islamicists often retain the dismissive term “Melkites” for Syriac- or Arabic-speaking Christians who agree with the doctrine of the Council of Chalcedon (and thus with the Byzantine Empire), here I will adopt the label “Chalcedonian Orthodox” for this community.

It is also necessary to say a word about the geographical scope of this paper, specifically regarding the physical extent of “Iraq” in this context. As the history of Mosul in the early twentieth century and in the past few years reminds us, boundaries are often made rather than given. Medieval Iraq has typically been defined as the region surrounding the lower courses of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, defined to the south by the emptying of those rivers into the Persian Gulf, to the west by the desert which separates it from Syria, and to the east by the mountains leading up to the Iranian plateau. The Khuzistan plain, sometimes considered part of Iraq and sometimes separated from it, will be excluded from this article. The northern boundary is more problematic. One can follow the Tigris and the Euphrates northward into Syria, eastern Anatolia, and eventually into the mountains inhabited by medieval Armenians and Kurds. Different medieval geographers drew the northern edge of Iraq at different places.25 Morony noted that initially the Mosul region was included as part of Iraq at the time of the Arab conquests, since it was conquered from the direction of al-Sawād (the agricultural region of southern Iraq), although it was joined to al-Jazīrah (upper Mesopotamia) from the 60s/680s onward.26 For the purposes of this paper, I include the plain around Mosul as part of Iraq, although not as far west as Sinjar. Mosul is included in part because that area was conquered and often ruled from southern Iraq, and in part as a case usefully different from developments further south. The recently studied trajectory of Islamization in Syria differs from that of Iraq in some instructive ways, and will also be used for comparison.27

Uncertain foundations

The initial conquests of Iraq were reported in traditions (akhbār) gathered into a geographical framework by Balādhurī in the third/late-ninth century. In addition to the common prosopographical and military interests of this genre, Balādhurī devotes a third of his section on southern Iraq (Sawād) to the foundation of the new cities, especially Kufa, al-Wāsiṭ, Baghdad, and Sāmarrāʾ, as well as lesser foundations such as al-Hāshimiyyah and al-Mutawakkiliyyah.28 The foundation of Basra receives a separate treatment later in the work.29 In the north, Mosul was founded as a garrisoned fort that grew into a walled city during the Marwanid period.30

These cities, of course, were centers of power and patronage for the Muslim ruling elite, and urban garrisons were the highest concentrations of the new religion in the region. As Morony points out, “At first the Muslim population was virtually identical with the army and its dependents who settled in the garrison towns.”31 Yet these four to seven centers were fewer than the garrisoned cities of Syria which formed the nodes of early Islamization in that province.32 The centrality of these Muslim centers in Iraq is suggested by Balādhurī’s report that an early garrison in al-Madāʾin was removed and consolidated into Kufa.33 He mentions very few Muslims living in Iraqi towns which predated the conquests, although his references to a church partitioned into a partial mosque in Hīt on the Euphrates, as well as mosques in al-Madāʾin, Anbar, and the northern city of Haditha suggest a Muslim presence in those towns.34 In general, however, compared to the Muslim garrisons of Syria, those in Iraq were more concentrated at fewer centers, which limited the social contacts which might lead to Islam’s diffusion.

The new cities did not restrict non-Muslim urbanization, however. Despite the famous anecdote about al-Ḥajjāj sending (non-Muslim) peasants away from the garrison cities, we should not think of Kufa or Basra as exclusively Muslim.35 Captives and slaves, as well as non-Muslim service workers and merchants, inhabited these cities very shortly after their founding, and we simply do not know how many such people there were. Kufa was so closely associated with the older Christian Arab city of al-Ḥīrah that Ibn Ḥawqal linked the former’s growth to the latter’s decline.36 Similarly, Basra was near to Pěrāth dě-Mayshān (al-Furāt), whose metropolitan archbishop may have moved into Basra by the beginning of the Abbasid period.37 Al-Wāsiṭ was founded across the river from Kashkar and encapsulated it with its non-Muslim population.38 Mosul grew up across from the Sasanian town of Nineveh, and around a pre-existing fort and a monastery called Mar Īshōʿyahb which had been founded at the end of the Sasanian period.39 Baghdad had a monastery within a dozen years of its founding.40 Sāmarrāʾ had multiple churches and monasteries in the 230s/850s, when al-Mutawakkil ordered their demolition according to a fourth/tenth-century historian.41 As counterintuitive as it seems, we cannot even be certain that Muslims remained a demographic majority within the cities they founded. These would be the prime sites of contact between Muslims and non-Muslims, but urban immigration rates may have sometimes outstripped conversion rates. In any event, non-Muslims long remained demographically dominant in the pre-Islamic cities of Iraq: Ibn Ḥawqal reports that Takrit, on the northern edge of Iraq, was still majority Christian in the fourth/mid-tenth century.42

In most agrarian societies, farmers outnumber city-dwellers by a large ratio, so this Muslim urban population was probably large only relative to other early medieval cities, not when compared to the rural non-Muslim population. Hugh Kennedy has estimated that the urban population of early Islamic Iraq was up to approximately half a million, but reliable estimates of the rural population are not available.43 J.C. Russell suggests a total population of nine to ten million in the Tigris–Euphrates valley in that period, although the basis for his estimate is not clear.44 By contrast, Colin McEvedy and Richard Jones critique the “normally sober Russell” for credulity in his interpretation of literary sources and implausible calculations; they instead propose that the premodern population of Iraq ranged between one and two and a half million, peaking around 180/800.45 The basis of their lower estimate is unstated, and therefore it cannot be evaluated.

The Muslim geographers include a report (khabar) that ʿUthmān b. Ḥunayf, the governor of Iraq for ʿUmar b. al-Khaṭṭāb, “sealed the necks of 550,000 uncircumcised men” (i.e., Christians and Zoroastrians), a practice of attaching lead seals to cords around the necks of defeated enemies, captives, and slaves, which was later associated with the payment of jizyah.46 If this number is reliable, it might imply a non-Muslim population in that period of at least one and a half to two and a half million, depending on the average number of dependents assumed for each adult male. This is close enough to the estimate of McEvedy and Jones to make one suspect that this report may be the ultimate basis for their proposed population total. Yet Morony noticed that this number pertains only to the area around Kufa, not to all of Iraq, and Balādhurī reported an alternate tradition which divided the tax-collection in al-Sawād between ʿUthmān b. Ḥunayf, west of the Tigris, and Ḥudhayfah b. al-Yamān east of it.47 On the other hand, Balādhurī cites a different report according to which ʿUthmān b. Ḥunayf accompanied Ḥudhayfah b. al-Yamān to Khāniqīn, a town east of the Tigris.48 This latter report may undercut the theory of a partition of Iraq between two tax collectors, and raises the question what the precise geographical scope of the previously reported neck-sealing activities might be.

It is equally unclear how to use a report included by Balādhurī that if ʿUmar b. al-Khaṭṭāb had divided al-Sawād among the Muslims, there would have been only three peasants per Muslim.49 Does this number imply that Muslims were one quarter of the population in this district? Or that the non-Muslim population of Iraq was three times the population of Muslims everywhere? Or were the “three peasants” three households, while the enumeration of Muslims perhaps included women? Or were both numbers exclusively adult men, but with a differential number of dependents among the military elite as among the peasant class? It is very difficult to move from literary references, even apparently precise ones, to numerical conclusions. The usefulness of numbers in literary sources for population estimates depends on many questionable factors, including the reliability of the scribal transmission of the texts, the stability of the oral transmission of the report (khabar), and, perhaps most dangerously, the ability of a newly arrived foreign ruler to count and tax every individual peasant. If Russell’s higher population estimate is more accurate, and if this report about ʿUmar’s governor still has any historical value, it may indicate instead that primitive Muslim jizyah collection was more haphazard and faulty than scholars have so far realized.

Outside of the cities, Balādhurī was particularly interested in Muslim landowners and land acquisition. He listed individual Muslim Arab landowners in southern Iraq by name, and how they acquired their property.50 He was careful to point out, both for the region of Diyār Rabīʿah around Mosul and separately for al-Furāt in southern Iraq, that these lands were not confiscated from legitimate owners; rather, the lands had been abandoned, or were previously uncultivable and reclaimed from swamp, or their owners converted to Islam.51 He enumerated categories of land claimed by ʿUmar b. al-Khaṭṭāb, from which subsequent caliphs granted properties to Arabs: properties of those who died or fled in the conquest, properties of the Persian royal family, uncultivated swamps and forests, and Dayr Yazīd.52 Balādhurī also mentioned a handful of Persian landowners (dahāqīn, sing. dihqān) who converted to Islam and whose land claims were subsequently recognized by the caliph, perhaps hinting at a perceived threat of confiscation.53 The fact that his only examples for this phenomenon come from obscure locations, which he enumerates, may suggest that conversions of the dihqān class was not the norm at such an early date. Although he lists four landowners in the south and none in the north, his disclaimer about land confiscation in northern Iraq suggests that some Arab landowners in the north adopted Islam.54

Balādhurī’s interest in Muslim land claims hints at differences between the rural societies of southern and northern Iraq, specifically the more rapid formation of a Muslim landowner class in the south contrasted with the larger numbers of Muslim Arab nomads in the north. This was not his intent, of course; his concern for the provenance of land claims was likely motivated by their relevance for legal or fiscal disputes in the third/ninth century when he compiled this work.55 Even so, on the basis of this source and others, Morony suggests that the Arab conquests reduced pastoral nomadism in favor of the new cities.56 By contrast, it is clear that many Bedouin remained in the north around Mosul, of whom many converted early to Islam.57 Nevertheless, as Chase Robinson points out, wealthy rural Christian landowners seem to have persisted longer and more prominently in the north.58 The fourth-/tenth-century Muslim geographer Ibn Ḥawqal, who generally had little interest in religious differences, still mentions these wealthy Christian landowners in a village not far from Arbil in the north.59 The process of land reclamation or bringing unfarmed land into cultivation, which Balādhurī indicates repeatedly for the “great swamp” north of Basra, may have enabled a more rapid rise in Muslim landowners in southern Iraq.60 This in turn may have encouraged a slightly greater rate of Islamization among the peasants brought in to work that land, as happened at a later period in East Bengal, and thus initiated a slow divergence in the religious makeup of society along a south-north axis.61

Mosques and monasteries

Unlike Ibn Ḥawqal, Muqaddasī, writing in the fourth/late-tenth century, claims to be interested in the relative preponderance of different religious groups.62 His discussion of religious groups, whether in particular locations or in Iraq as a whole, is nevertheless far from systematic. He mentions several mosques in towns, which indicates a degree of diffusion of Islam beyond the garrison cities and caliphal capitals founded by Muslims. However, it also indicates that the presence of a mosque in such towns could not be taken for granted. Indeed, Muqaddasī mentions two towns both named al-Jāmiʿayn (“the two mosques”), one in the south near Kufa, and one further north, near Sāmarrāʾ.63 This suggests that for a town to have two mosques was so unusual as to change the name of the settlement. Yet apart from the six district capitals of Iraq, he mentions mosques in fewer than half of the towns which he singles out for description, and fewer than a fifth of the towns which he names.64 His list of mosques is likely incomplete, as his list of villages certainly is, and of course these proportions cannot be taken as a percentage of all villages. But we might presume that his selection of villages was biased in favor of “important” settlements which had attracted the attention of Muslim elites for one reason or another, and such towns and villages were also more likely than other (“unimportant”) settlements to have a mosque. In other words, settlements without mosques were probably more preponderant in the Iraq of Muqaddasī’s day than in the list of settlements which he presents.

Muqaddasī also asserts that there were “many” shrines in Iraq, and yet the examples he cites are almost exclusively urban. He mentioned one site associated with Abraham and one with Noah, which may have been shared with the local Jewish and Christian populations rather than exclusively Muslim.65 Apart from these, the monuments of ʿAlī and Ḥusayn are the only specifically Muslim holy places which Muqaddasī did not locate within Kufa, Basra, Baghdad, or al-Madāʾin.66 By contrast, he lists fifteen Muslim shrines in Basra, six in Baghdad, one in al-Madāʾin, and one in Kufa, and he alludes to the existence of others.67 Coupled with his references to town mosques, this may suggest that in Muqaddasī’s time, late in the fourth/tenth century, Islam was still primarily an urban phenomenon beginning to spread into towns and some larger villages. If this is the case, then Muslims must have remained significantly less than half, perhaps no more than a quarter, of the total population of Iraq at this time, far less than the 90 percent estimate prevailing in current scholarship. Such a small proportion of Muslims would explain why Muqaddasī began his discussion of religious groups in Iraq, even before listing the different Islamic groups which interested him, by stating briefly, “There are many Magians [i.e. Zoroastrians] in this region, and its dhimmah [sic] are both Christians and Jews.”68 The fact about religious diversity in Buyid Iraq which Muqaddasī found most noteworthy was the large numbers of non-Muslims.69

Although Muqaddasī evinced no specific interest in any non-Muslim population above others, the fourth-/tenth-century Kitāb al-Diyārāt of Shābushtī reveals that the Christian monasteries of Iraq continued to function largely unhindered into the Buyid period. Scholars may dispute whether the content of such a literary work, designed at least as much to entertain as to inform, is more factual or fictive.70 Yet this debate has largely taken place over the value of the particular anecdotes related, anecdotes relating the personal interactions between elite Muslim men and Christians of various ages and genders, ranging from the miraculous to the seductive. Just as hagiography often yields reliable social information in its incidental details, the “scenery” for the entertaining anecdotes may be more consistently factual than the events narrated. Among incidental details we might include whether a monastery was inhabited or not, and the dates of individual monasteries’ particular festivals; it is not clear how such details, not entertaining in themselves and unnecessary to understand particular tales, would serve the belle-lettristic purpose. As Kilpatrick notes, Shābushtī also indicates at one point that he had visited Basra in southern Iraq, and was informed about a marvel inside a monastery in northern Mesopotamia by the Christians of that region, perhaps suggesting that he traveled the full length of Iraq and wrote from firsthand knowledge.71 This fourth-/tenth-century author mentions thirty-six monasteries in Iraq and around Mosul.72 Of these, he describes at least twenty of them as inhabited by monks, and probably at least three more were functioning. By contrast, he explicitly identifies only three monasteries as ruined, abandoned, or inhabited by travelers, leaving ten whose status at the end of the fourth/tenth century is entirely unclear. Even if all ten of these were abandoned at that time, most of the monasteries known to Shābushtī continued to function. Many of these had functioned continuously since the Sasanian period, while others were founded more recently.73

There are many ways scholars might misinterpret these numbers, which we must carefully avoid. No conclusion can be drawn from the fact that Shābushtī lists more active monasteries than Muqaddasī lists towns with mosques; both lists are incomplete, and the two texts were compiled for different purposes. The ratio between the two lists cannot be extrapolated to the religious demographics of Iraq’s population as a whole, for two reasons, one mathematical and one historical. First, the mathematical reason: without knowing the total numbers of each category, the ratio of two non-random samples is meaningless. Second, even if the ratio of monasteries to mosques were known, the two types of buildings performed very different religious and social functions, so it is by no means clear that a Muslim population would have the same number of mosques as a comparable Christian population would have monasteries.74 But the numbers of active, uncertain, and abandoned monasteries also cannot be generalized to the greater (unknowable) set of all Iraqi monasteries, to suggest perhaps a bounded range on the ratio of Islamization since the conquests three-and-a-half centuries earlier. Medieval monasteries were like modern American business start-ups: most were small, never famous, and of brief duration, many monasteries not long surviving their founders, so even in the best of circumstances we would expect a certain number of failed monasteries and some rapid turnover.75 In short, Shābushtī’s list of active, uncertain, and abandoned monasteries cannot be used computationally.

But it can be used culturally. What these numbers do indicate is that when one fourth/tenth-century Muslim author such as Shābushtī imagined monasteries in Iraq, some of which he may have visited himself, he imagined them not solitary and deserted in a landscape, but peopled with monks. Generalizing from his assumptions to those of his educated Muslim audience is difficult for all the usual reasons, but we might venture a few suggestions based on Shābushtī’s rhetoric. It was evidently not surprising to Shābushtī’s audience for a monastery to be inhabited, since it could be indicated tersely with a single word such as ʿāmir (“occupied”).76 Shābushtī specified whether the monastery was occupied or abandoned in a slight majority of cases, which suggests that he did not expect his audience to assume one way or the other. Without such an overarching assumption, the fact that most of the monasteries which he mentions were occupied probably indicates that the cities, towns, and rivers of Iraq were still accustomed to seeing active, rather than ruined, monasteries in the fourth/tenth century.

The continuation of Christian infrastructure

A changing geographical distribution of the Christian presence in Iraq should also be reflected by shifting locations of bishops and metropolitan archbishops. Like monasteries, the number and extent of bishoprics was affected extremely slowly by Islamic rule. Three nearly complete lists of Eastern Syriac bishops, each evidently independent of the others,77 survive from the Buyid period or earlier: one included in the acts of a church council in 410 CE during the Sasanian period, one composed at the end of the third/ninth century by Ilyās b. ʿUbayd, the Eastern Syriac metropolitan of Damascus, and one in the Mukhtaṣar al-ākhbār al-bīʿiyyah, a text composed anonymously in the fifth/early-eleventh century.78 The first list was a component of a Christian hierarchical reform within the Sasanian Empire to establish increased centralized control by the catholicos, while the second was composed as part of a canon law text in the Abbasid Empire. The purpose for the composition of the third is not fully clear, inserted in the middle of historical reports pertaining to the pre-Islamic period, even though the list does not reflect pre-Islamic conditions.

Like monasteries, we need to be careful not to treat the numbers of bishops as proxies for Christian population levels.79 The shape of the hierarchy tended to be conservative, changing more slowly than the growth, movement, or decline of Christian populations. Thus the Eastern Syriac patriarch continued to be headquartered at the Sasanian capital of al-Madāʾin until twenty years after the foundation of Baghdad, a century and a half after the Muslim Arab conquest of the Sasanian Empire. Nevertheless, medieval Syriac churches did not maintain merely titular dioceses, offices with the rank of bishop but without real local churches or parishes under them, as the Roman Catholic Church did until the middle of the twentieth century. Thus episcopal lists might indicate Christian institutional strongholds, and perhaps important Christian centers. David Wilmshurst has raised the concern, however, that these lists of dioceses were even more conservative than the actual shape of the ecclesiastical hierarchy at the time each list was composed, continuing to include individual bishoprics that had already become defunct.80 Comparing lists of dioceses with medieval historians’ references to specific bishops of each diocese, as collected by Jean-Maurice Fiey, acts as a control upon suspected anachronistic features of the lists.81 But since medieval historians were not systematic in their references to particular bishops, and tended to mention primarily those who were closer to the seats of power in central Iraq, the absence of a chronicle’s reference to a particular minor diocese far from the capital cannot be taken as strong evidence for the abolition of that diocese.

Wilmshurst’s concern about lists being anachronistic is plausible, yet internal features of each list suggest the degree to which each was up-to-date when it was authored. For example, the anonymous author of the Mukhtaṣar noted that the metropolitanate of Bardaʿah and Armenia was abolished by one Catholicos Yuḥannā (presumably either Yuḥannā V, r. 390–401/1000–1011, or Yuḥannā VI, r. 402–411/1012–1020) and reduced to a diocese based in Khilāṭ.82 This must have been a very recent event for an author writing in the first decades of the fifth/eleventh century. He also noted that the diocese of al-Qubbah was merged into Kashkar, and its rank was taken over by the bishop of al-Bawāzīj.83 According to the historian ʿAmr b. Mattā (eighth/fourteenth century), this exchange happened under Catholicos ʿAbdīshōʿ (r. 352–376/963–986), no more than fifty years before the Mukhtaṣar was composed, and perhaps within the lifetime of the author.84 Ilyās b. ʿUbayd, of course, wrote before the transfer and listed al-Bawāzīj among the bishops of Beth Garmay, but in this case, a later scribe updated Ilyās’s list in two places to mention that al-Bawāzīj was removed from the metropolitanate of Beth Garmay and made subject to the catholicos instead.85 Another scribal note indicates that the diocese of Bādarāyā and Bākusāyā was abolished and merged into the diocese of Kashkar.86 We do not know when that happened, but in the Mukhtaṣar it is still listed as a separate diocese, and Fiey indicates that bishops of that diocese are attested into the fifth/eleventh century, suggesting that this merger was a post-Buyid development, incorporated into Ilyās’s list by a later scribe.87

These notes indicate that the authors composed these lists in light of recent developments, and scribes expected the lists to be up-to-date, sometimes adding notes to reflect developments after the original composition. Furthermore, although it was rare for ecclesiastical historians to describe changes to the ecclesiastical hierarchy, the references to individual bishops assembled by Fiey demonstrate the historical accuracy of at least the bulk of the shared elements in each list. Rather than supporting Wilmshurst’s suspicion that these documents were already out-of- date when they were composed, it seems that they provide some reliable information on the period of their composition.

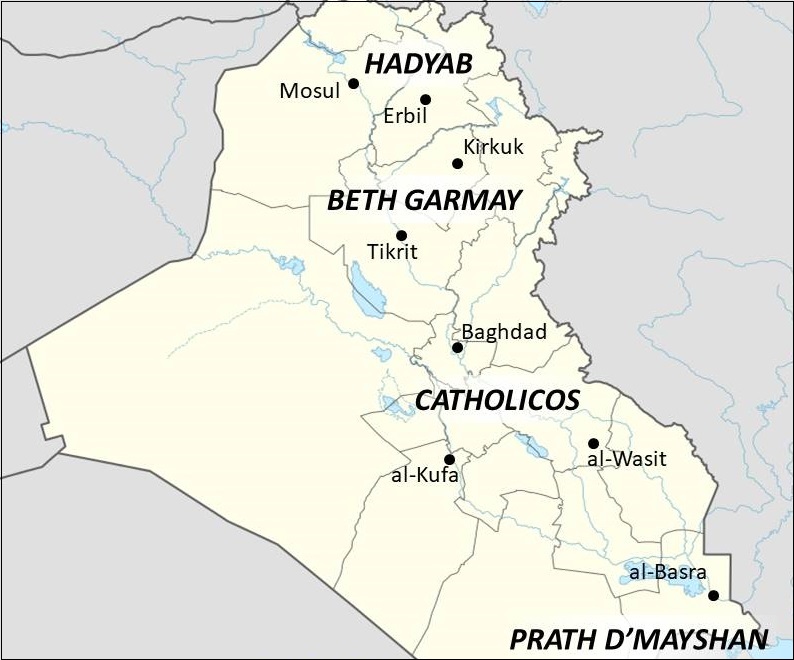

Throughout the late Sasanian and early Islamic periods, most of Iraq was divided among four metropolitans: from south to north, Pěrāth dě-Mayshān, Beth Ārāmāyē (the province of the catholicos), Beth Garmay, and Ḥadyab (see Gallery Image B). While each changed between the Sasanian era and the fifth-/eleventh-century list considered here, all three lists show more commonality with one another than difference (apart from changing names for the same places), a fact all the more surprising given the lists’ mutual independence.

In the north, the attraction of new Arab Muslim centers is seen in shifting bishop locations, but later lists include as many dioceses as earlier. The Synod of 410 identified the metropolitan’s seat as Arbil, with suffragan (subordinate) bishops at Beth Nūhadrā, Beth Běgash, Beth Dasin, Ramōnīn (?), Beth Mihqart (?), Dabriyānōs (?), and Ravranḥasan (?).88 But there seems to be some textual corruption, since Briyānōs is then given as the name of the bishop of Beth Běgash later in the same text, and the other three names at the end of the list are not otherwise known as dioceses or even place-names at any period.89 By the end of the Sasanian period, the city of Nineveh had obtained a bishop, as had the Sasanian “new town” Nawgird in northern Iraq, later known as Haditha.90 Ilyās’s list includes all of these dioceses with the exception of the four dubious ones from the Synod of 410, as well as a new diocese for the Bedouin (al-Bādiyyah), and records that the headquarters of the metropolitan moved from Arbil to the new city of Mosul.91 The list in the Mukhtaṣar differs only in the consolidation of the bishop of Nineveh with the metropolitan of Mosul (indicated under the archaic name of the metropolitanate, Ḥazzah).92 If we neglect the four dubious dioceses listed in the acts of the Sasanian synod, the only changes in the north of Iraq reflected in the Abbasid and Buyid episcopal lists were the movement of the metropolitan’s headquarters to the new city of Mosul, the unification of the bishop of Nineveh with the metropolitan of Mosul, and the creation of a new bishop “for the Bedouin.” In other words, northern Iraq’s ecclesiastical hierarchy was largely stable during the first four centuries of Islamic rule.

In the region of Beth Garmay around Kirkuk and Takrit, there seems to have been some shuffling of diocese names, centers, and boundaries, and one diocese was transferred from this metropolitan to the control of the catholicos in the fourth/mid-tenth century, but each list contains the same number of bishops in this province. The Synod of 410 listed suffragan bishops at Shahrqart, Lashōm, Ārīwān, Daraḥ, and Ḥaravgělal.93 Ilyās listed Shahrqart, al-Bawāzīj (the Arabic name of Ārīwān), Khānījār, and Lashōm, and in place of the last two, introduced Daqūqā and Darābād.94 The odd thing is that the historian ʿAmr b. Mattā seems to regard Lashōm and Daqūqā as alternate names for the same place, though Ilyās clearly distinguished them in his list.95 Finally the Mukhtaṣar kept Shahrqart and Daqūqā, reintroduced Ḥaravgělal as Ḥarbath Jalū, and replaced al-Bawāzīj (which moved to the jurisdiction of the catholicos) and Darābād with dioceses for Tāḥil and Shahrazūr.96 Although there is confusion as to the names and locations of dioceses, each list agrees that there were five suffragan bishops to the metropolitan, a detail which suggests that there was no institutional weakening, whatever reshuffling might have occurred.

In Beth Ārāmāyē, the province of the catholicos in central Iraq around al-Madāʾin and Baghdad, in addition to absorbing one diocese from Beth Garmay, four new dioceses were created in the second/eighth and third/ninth centuries, although one of these seems to have lapsed by the fourth/tenth century. Our analysis is hindered by the fact that the acts of the Synod of 410 did not list the suffragan bishops of the catholicos, only those of the other metropolitans, but none of the dioceses mentioned by Fiey in this region seem to have lapsed in the early Islamic period. Instead, Ilyās’s list includes all seven known suffragan dioceses of the late Sasanian period, as well as four new dioceses founded in the Islamic period: ʿUkbarā, Niffar, al-Qaṣrā, and ʿAbdāsī.97 The list in the Mukhtaṣar is the same as Ilyās’s, but omits ʿAbdāsī, replacing it with the diocese of al-Bawāzīj which had been transferred from Beth Garmay.98 In sum, the province of the catholicos continued to have the largest number of suffragan bishops of any metropolitanate in Iraq, and was larger in the middle of the Buyid period than in the pre-Islamic period, suggesting that the first four centuries of Islamic rule were, on the whole, ones of growth rather than decline for the ecclesiastical hierarchy in central Iraq. But the loss of ʿAbdāsī, even if offset by the annexation of al-Bawāzīj from the province to the north, perhaps indicates a slight amount of institutional slippage in the fourth/tenth century after the period of growth under the earlier Abbasid caliphate.

It is only in the south, around Basra, that we see the unreplaced loss of dioceses. At the Synod of 410, the metropolitan of Pěrāth dě-Mayshān had three suffragan bishops: Karkā, Rīmā, and Nahargūr.99 Ilyās renamed the metropolitan archdiocese after the new Muslim city of Basra, and gave Arabic names for Karkā (Dastumaysān) and Rīmā (Nahr al-Marā), but Nahargūr was nowhere in view.100 By the time of the Mukhtaṣar, Nahr al-Marā continued under the name Nahr al-Dayr, but Dastumaysān no longer had its own bishop, having been combined into the metropolitan’s title, even if this loss was partially offset by a new diocese of Najrān, presumably the settlement of the Christian Arabs expelled from Arabia.101 Thus, in southern Iraq around Basra, we see the loss of one diocese before 280s/900 and another incorporated into the title of the metropolitan by 390/1000, large losses in a metropolitan province with only a few suffragan bishops at any period.

Taken together, these three episcopal lists suggest a modest growth of the hierarchy in central and northern Iraq, especially in the high Abbasid period, but some shrinking in the south. The slow changes to monastery and ecclesiastical hierarchy distributions suggest some conclusions about demography as well, given the economic basis for monasticism in Iraq and the fact that all bishops in this region were also monks.102 As Cynthia Villagomez has pointed out, in the early Islamic period, the Church of the East renounced the ideal of self-supporting monasteries of laboring monks in favor of the acquisition of wealth by monasteries, whether in the forms of endowments or donations.103 Villagomez repeatedly noted the centrality of donations in the monastic economy, including in the primary sources.104 While some Muslims, even Muslim rulers, gave money to monasteries, the majority of donors would have been Christian, and increasing Islamization would progressively defund the ecclesiastical hierarchy and the monasteries in Iraq.105 The fact that the hierarchy and the monasteries had been so little affected by almost four centuries of Muslim rule, including by the economic crisis of fourth-/tenth-century Iraq, suggests that there was no massive defunding such as we would expect had 90 percent of the Iraq’s Christian population converted to Islam, as most scholars assume.106 It would seem that the Christian populations of Iraq preserved sufficient “social density,” to use Morony’s term, to maintain distinctively Christian social structures, and thus to maintain Christian identities and even to assimilate new converts, if Morony’s suggested link between “social density” and resistance to assimilation holds.107

Conclusion

As the Muslims’ new foundation of al-Wāsiṭ grew, it did so at Kaskar’s expense, both physically and notionally. Yet Kaskar lingered, in a variety of different forms. Shābushtī mentioned a monastery named ʿUmr Kaskar, which he located “below al-Wāsiṭ, on the eastern side of it,” where the Christian bishop resided.108 Two centuries later, the famous geographer Yāqūt al-Ḥamawī knew Kaskar as an agricultural region.109 And the fact that al-Wāsiṭ was reported to occupy both sides of the Tigris River indicates that Kaskar did not in fact decline, but was rather incorporated into al-Wāsiṭ and lost its separate identity.110 The Sasanian city did not in fact go away, but continued under its Islamic name. We cannot say what proportion of former Kaskar, renamed “eastern al-Wāsiṭ,” was Muslim or not at any given period, but the data reviewed above indicate that the literary amnesia outstripped the social Islamization “on the ground” throughout Iraq. Non-Muslims were not gone, even if their places were renamed.

The persistence of monasteries and dioceses of the Church of the East, reliant as they are on the donations of the faithful, suggest that this particular Christian denomination did not experience any substantive Islamization before the end of the first millennium, with perhaps only the first hints of coming changes in the south of Iraq around Basra. Yet Eastern Syriac Christianity and Islam were not the only religions in late antique and early Islamic Iraq; does the persistence of the former tell us anything about the progress of Islamization more generally? One might surmise that other religious groups fueled the conversion to Iraq at the rate proposed by Bulliet, so that Iraq might be presumed to be 90 percent Muslim before 390/1000.111 Beyond the Church of the East, there were at least two other Christian groups in Iraq, the Syriac Orthodox (so-called “Jacobites”) and the Chalcedonian Orthodox (so-called “Melkites”). In addition, significant Jewish populations continued in Iraq, as well as the formerly state-sponsored Zoroastrians and new religions such as Manichaeans and Mandaeans.112 In the absence of census records, the relative proportion of these groups is unknowable, but there are hints. The depth of hierarchy of the Church of the East in Iraq far exceeded that of the other Christian denominations, indicating, if not the precise proportion of populations, at least which ecclesiastical structure was best at securing a share of agricultural produce.113 We might expect a certain amount of slippage among Christian denominations, but it is hard to imagine that the vast majority of Christians in Iraq did not worship with priests appointed by the Church of the East hierarchy based in Baghdad, rather than the more distant hierarchies of the Western Syriac denominations. Thus the lack of mass conversion to Islam among the Church of the East is suggestive for Iraqi Christianity more broadly.

Comparing the Christian and Jewish populations in early Islamic Iraq is not easy. Scholars have previously emphasized the urbanization of the Jewish population, but Philip Ackerman-Lieberman has recently argued that most of the region’s Jews continued in agricultural pursuits until Iraq’s economic crisis in the fourth/tenth century.114 The Jewish exilarchate and Iraq’s two geonic academies (yeshîvôt) of Sura and Pumbedita likewise continued, though not uninterruptedly, into the fifth/eleventh century, revealing an institutional continuity similar to that experienced by the Church of the East.115 The economic basis of these institutions was perhaps mainly local Jewish populations rather than donations from abroad, even if the latter generated more literature and thus more modern scholarly discussion.116 Robert Brody remarks that, while the number of Jews who did convert is unknowable, such conversions did not seriously impinge upon the Iraqi Jewish communities’ “integrity.”117 If few Jews or Christians converted during the first millennium, then most of the converts to Islam in Iraq during the early Islamic period were not from its fellow Abrahamic religions.

We are even less informed about the relative demographic strength of Zoroastrians as compared to Jews and Christians. The newer religions such as Manichaeism and Mandaeism are not mentioned in Muqaddasī’s statement about non-Islamic religions in Iraq,118 which may indicate that they were less significant for understanding the region broadly.119 But Zoroastrianism had been the state-supported religion of the Sasanian dynasty, so it may have claimed a large number of followers in the region around the former imperial capital in southern Iraq. And unlike Judaism and Christianity, the ancient Persian religion did suffer significant institutional rupture in the early Islamic period. We might therefore expect Islamization in Iraq to be driven by the conversion of Zoroastrians, even if some of them chose Christianity over its newer monotheistic cousin.120 Nevertheless, Muqaddasī could still, in the Buyid period in the late fourth/tenth century, claim that Iraq had “many Magians,” so it is unclear even how many of them had adopted Islam by the end of the first millennium.

This recapitulation of Iraq’s religious diversity might suggest that most converts to Islam came neither from Christianity nor Judaism, but we do not know if at the time of the Arab conquests, those two monotheistic religions together accounted for ten percent of the region’s population, ninety percent, or anywhere in between. Yet if Christians and Jews both preserved their “communal integrity,” and if there were still “many Magians” in Iraq in the fourth/late-tenth century, it is unclear from which sources a 90 percent Muslim supermajority, as scholars presume for Iraq by the year 390/1000, might have been drawn. Indeed, regardless of the relative proportions among different non-Muslim populations, Muqaddasī’s testimony that mosques were only beginning to penetrate Iraq’s many agricultural villages in the fourth/tenth century suggests that the religion of the rulers was also almost exclusively an urban religion. The urban character of Islam before 390/1000, combined with the general economic principle that the populations of agrarian societies are overwhelmingly rural, calls into question whether Islamization had even reached a third of Iraq’s population, much less a majority. Bulliet’s proposed conversion curve must be considerably too steep.

Islam’s weak penetration into the Iraqi countryside even by the fourth/tenth century should change how we understand the shape of early Islamic history in Iraq, in precisely the period when Iraq ruled the Muslim world. If, indeed, there were very few Muslims in Iraq’s smaller towns and villages, then, in fact, the third/ninth century was no tipping point, no “age of conversions,” but rather a period when most people kept on keeping on. Scholars can stop interpreting elite texts in the context of a popular wave of conversions which mostly likely had not yet happened; religious diversity was much more continuous from the late Sasanian period into the rule of the Buyid dynasty four centuries later. Non-Muslims were pervasive in Iraq throughout the period of Abbasid power, and Muslim texts might be more thoroughly contextualized by an awareness of the religious other, even when unmentioned. Muqaddasī’s list of town mosques suggests that rural Islamization, and therefore demographic Islamization, was beginning rather than ending as the Buyid amīrs captured Baghdad. Indeed, David Wilmshurst has demonstrated that the period of rapid transformation for Iraqi dioceses is later, around 1200 in southern Iraq, and after 1300 in the north.121 If we are looking for an “age of conversions” in Iraq, we should perhaps look to the eve of the Mongol conquest rather than to the Samarran period of the Abbasid Caliphate.

About the author

Thomas A. Carlson is an Assistant Professor of Middle Eastern History at Oklahoma State University. His research explores Christianity, Islam, and religious diversity in the medieval Middle East. His book Christianity in Fifteenth-Century Iraq is published by Cambridge University Press (2018). He is also a former editor of the Syriac Gazetteer, and is developing a digital reference work to document the religious, ethnic, and linguistic diversity in the medieval Middle East.

Notes

- Aḥmad b. Yaḥyā al-Balādhurī, Kitāb Futūḥ al-buldān, ed. M. J. de Goeje (Leiden: Brill, 1866), 275–277, 290, 346–347; idem, The Origins of the Islamic State, trans. Philip K. Ḥitti and Francis C. Murgotten (2 vols.; New York: Columbia University, 1916-1924), 1.434–437, 449–450; 2.60–61. ↑

- C. Edmund Bosworth (ed.), Historic Cities of the Islamic World (Leiden: Brill, 2007), 550–551. The course of the Tigris has subsequently shifted so that the ruins of al-Wāsiṭ are no longer along the river. ↑

- Jean-Maurice Fiey, Pour un Oriens Christianus novus: répertoire des diocèses syriaques orientaux et occidentaux (Stuttgart: Orient-Institut der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, 1993), 102–103. ↑

- Abū’l-Qāsim Muḥammad b. ʿAlī al-Naṣībī Ibn Ḥawqal, Kitāb Ṣūrat al-arḍ (Beirut: Dār Maktabat al-Ḥayāh, 1964), 214; idem, Configuration de la terre (Kitab surat al-ard), trans. Johannes Hendrik Kramer and Gaston Wiet (2 vols.; Beirut: Commission Internationale pour la Traduction des Chefs-d’Oeuvre, 1964), 1.231; Shams al-Dīn Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad b. Aḥmad al-Muqaddasī, Aḥsān al-taqāsīm fī maʿrifat al-aqālīm: Muḥammad b. Aḥmad al-Muqaddasī, Descriptio Imperii Moslemici, ed. M. J. de Goeje (2nd ed.; Bibliotheca Geographorum Arabicorum 3; Leiden: Brill, 1906), 118; idem, The Best Divisions for Knowledge of the Regions: a Translation of Aḥsan al-taqāsīm fi maʿrifat al-aqālīm, trans. Basil Anthony Collins (Reading, UK: Centre for Muslim Contribution to Civilization, 1994), 99. ↑

- Demographic Islamization, i.e., the process by which a region’s population comes to identify as Muslim, is only one variety of Islamization among others, such as the Islamization of government, coinage, or culture. See Andrew C. S. Peacock, “Introduction,” in Andrew C. S. Peacock (ed.), Islamisation: Comparative Perspectives from History (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2017), 1–18; Thomas A. Carlson, “When Did the Middle East Become Muslim? Trends in the Study of Islam’s ‘Age of Conversions,’” History Compass 16 (2018). ↑

- Richard W. Bulliet, Conversion to Islam in the Medieval Period: An Essay in Quantitative History (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979), 82. Alwyn Harrison suggested, and Richard Bulliet later affirmed, that his proposed percentages are not of the total population, but only “of the ultimate unquantifiable total of converts”: Harrison, “Behind the Curve: Bulliet and Conversion to Islam in al-Andalus Revisited,” Al-Masaq: Islam and the Medieval Mediterranean 24 (2012): 35–51, 37–38; Richard W. Bulliet, “The Conversion Curve Revisited,” in Peacock (ed.), Islamisation, 69–79, 71. It is difficult to see how changing percentages of unquantifiable phenomena could be mathematically or historically meaningful, but in any event, given that Iraq today is 95 percent Muslim or more, the practical difference between the two interpretations seems negligible. ↑

- Michael G. Morony, Iraq after the Muslim Conquest (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984), 522. He also cites earlier scholarship by Dennett and (for Egypt) Lapidus indicating that the decline in poll-tax receipts during the Umayyad period was not evidence for mass conversion: ibid., 119. On the use of these terms, see below. ↑

- Bulliet, Conversion to Islam, 36–37; Richard W. Bulliet, “Conversion Stories in Early Islam,” in Michael Gervers and Ramzi Jibran Bikhazi (eds.), Conversion and Continuity: Indigenous Christian Communities in Islamic Lands, Eighth to Eighteenth Centuries (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1990), 123–133, 128–132; Morony, Iraq after the Muslim Conquest, 273, 524. ↑

- Morony, Iraq after the Muslim Conquest, 381–382. ↑

- Ibid., 212, 305, 354, 361. ↑

- Bulliet remarked the extreme paucity of Islamic conversion stories from the first three centuries; “Conversion Stories,” 123. ↑

- Wadi Haddad, “Continuity and Change in Religious Adherence: Ninth-Century Baghdad,” in Gervers and Bikhazi (eds.), Conversion and Continuity, 33–53. ↑

- Giovanna Calasso, “Récits de conversions, zèle dévotionnel et instruction religieuse dans les biographies des ‘gens de Baṣra’ du Kitāb al-Ṭabaqāt d’Ibn Sa’d,” in Mercedes García-Arenal (ed.), Conversions islamiques: identités religieuses en islam méditerranéen (Paris: Maisonneuve et Larosse, 2001), 19–47. ↑

- Sidney H. Griffith, The Church in the Shadow of the Mosque: Christians and Muslims in the World of Islam (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008). ↑

- David Bertaina, Christian and Muslim Dialogues: The Religious Uses of a Literary Form in the Early Islamic Middle East (Piscataway: Gorgias Press, 2011). ↑

- Haddad, “Continuity and Change,” 50; Griffith, The Church in the Shadow of the Mosque, 20, 35, 56–57, 99; Bertaina, Christian and Muslim Dialogues, 106–108, 238. The phrase is Haddad’s. Oddly, Griffith seems to assert a slower timeline of conversion than Bulliet on the basis of Bulliet’s 1979 book, suggesting Muslims were not even a majority in Iraq into the fifth/eleventh century; The Church in the Shadow of the Mosque, 11. He gives no evidence or argument apart from Bulliet for the view. Gerrit Reinink argues that fear of mass conversions drove the Christian clergy to develop anti-Islamic literature already from the end of the first/seventh century, a fear which was increasingly justified by social developments; “Following the Doctrine of the Demons: Early Christian Fear of Conversion to Islam,” in Jan N. Bremmer, Wout Jac van Bekkum, and Arie L. Molendijk (eds.), Cultures of Conversion (Groningen Studies in Cultural Change 18; Leuven: Peeters, 2005), 127–138. ↑

- Michael Philip Penn, Envisioning Islam: Syriac Christians and the Early Muslim World (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015), 167–179, esp. 168. ↑

- Richard W. Bulliet, “Conversion-Based Patronage and Onomastic Evidence in Early Islam,” in John Nawas and Monique Bernards (eds.), Patronate and Patronage in Early and Classical Islam (Leiden: Brill, 2005), 246–262, 251–252. ↑

- Ibid., 261. ↑

- Zayde Antrim, Routes and Realms: The Power of Place in the Early Islamic World (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 1–2. ↑

- Compare the approaches of Thomas A. Carlson, “Contours of Conversion: The Geography of Islamization in Syria, 600–1500,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 135 (2015): 791–816, 796–797 and Antrim, Routes and Realms, 3. ↑

- Tamer el-Leithy points out that medieval Muslim authors did not attach political significance to relative demography, and therefore did not record it; “Coptic Culture and Conversion in Medieval Cairo, 1293–1524 A.D.” (Ph.D. diss., Princeton University, 2005), 27, especially n. 71. ↑

- Jack B. V. Tannous, “Syria between Byzantium and Islam: Making Incommensurables Speak” (Ph.D. diss., Princeton University, 2010), 430–480; Uriel Simonsohn, “Conversion to Islam: A Case Study for the Use of Legal Sources: Conversion to Islam,” History Compass 11 (2013): 647–662; idem, “‘Halting Between Two Opinions’: Conversion and Apostasy in Early Islam,” Medieval Encounters 19 (2013): 342–370; Penn, Envisioning Islam, 142–182. ↑

- For a scholarly rejection of the polemical label “Nestorian,” see Sebastian P. Brock, “The ‘Nestorian’ Church: A Lamentable Misnomer,” Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester 78 (1996): 23–35. ↑

- Ibn Ḥawqal placed the boundary between Iraq and al-Jazīrah at Takrit, whereas Balādhurī and Muqaddasī included in Iraq the smaller city of al-Sinn, which is almost fifty miles further north at the junction of the Tigris and the Lower Zāb: Balādhurī, Futūḥ, 265; idem, Origins, trans. Ḥitti and Murgotten, 1.422; Ibn Ḥawqal, Ṣūrat al-arḍ, 208; idem, Configuration, trans. Kramer and Wiet, 1.225; Muqaddasī, Descriptio, 115; idem, Regions, trans. Collins, 97. The fact that al-Sinn is depicted on Ibn Ḥawqal’s map of Iraq does not imply that he agreed with the others, since Mosul is also depicted there, while he describes both al-Sinn and Takrit under the section on al-Jazīrah: Ibn Ḥawqal, Ṣūrat al-arḍ, 203, 205, 210; idem, Configuration, trans. Kramer and Wiet, 1.219, 223, 226. On the other hand, Muqaddasī included not only Anbar in Iraq but also Hīt, fifty miles northwest up the Euphrates from Anbar, while Balādhurī assigned Hīt to al-Jazīrah and Anbar to Iraq, and Ibn Ḥawqal assigned both Hīt and Anbar to al-Jazīrah: Balādhurī, Futūḥ, 179; idem, Origins, trans. Ḥitti and Murgotten, 1.279; Ibn Ḥawqal, Ṣūrat al-arḍ, 205; idem, Configuration, trans. Kramer and Wiet, 1.222; Muqaddasī, Descriptio, 115; idem, Regions, trans. Collins, 97. ↑

- Morony, Iraq after the Muslim Conquest, 134–136. ↑

- Carlson, “Contours of Conversion.” ↑

- Balādhurī, Futūḥ, 275–292, 294–298; idem, Origins, trans. Ḥitti and Murgotten, 1.434–452, 457–461. ↑

- Balādhurī, Futūḥ, 346–350; idem, Origins, trans. Ḥitti and Murgotten, 2.60–66. ↑

- Balādhurī, Futūḥ, 332; idem, Origins, trans. Ḥitti and Murgotten, 2.32–33. The rapid development of Mosul by the Marwanids was proposed by Chase F. Robinson, Empire and Elites after the Muslim Conquest: The Transformation of Northern Mesopotamia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 72–89. ↑

- Morony, Iraq after the Muslim Conquest, 431. ↑

- Carlson, “Contours of Conversion,” 798–799. ↑

- Balādhurī, Futūḥ, 275; idem, Origins, trans. Ḥitti and Murgotten, 1.434. ↑

- Balādhurī, Futūḥ, 179, 289–90, 333; idem, Origins, trans. Ḥitti and Murgotten, 1.279, 449; 2.34. Morony mentions these mosques as the earliest in Iraq; Iraq after the Muslim Conquest, 432–433. ↑

- Muḥammad b. Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, The Empire in Transition: The Caliphates of Sulaymān, ʿUmar, and Yazīd, A.D. 715–724/A.H. 97–105, trans. David Stephan Powers (History of al-Ṭabarī 24; Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989), 165. ↑

- Ibn Ḥawqal, Ṣūrat al-arḍ, 215; idem, Configuration, trans. Kramer and Wiet, 1.232. Morony cites evidence that the shift was not immediate, however; as late as the third/ninth century, al-Ḥīrah was still Christian and still larger than Ḥulwan; Iraq after the Muslim Conquest, 234. Al-Ḥīrah had a Christian bishop from the pre-Islamic period into the fifth/eleventh century, who may be presumed to have shifted his residence to Kufa at some undetermined point; see Jean Baptiste Chabot (ed.), Synodicon Orientale ou Recueil de Synodes Nestoriens (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1902), 36; Giuseppe Simone Assemani, Bibliotheca Orientalis Clementino-Vaticana (3 vols. in 4; Rome: Typis Sacrae Congregationis de Propaganda Fide, 1725), 2.458; Buṭrus Ḥaddād (ed.), Mukhtaṣar al-akhbār al-bīʿiyyah: wa-huwa al-qism al-mafqūd min “al-Tārīkh al-Siʿirdī”(?) (Baghdad: Maṭbaʿat al-Dīwān, 2000), 123. ↑

- Chabot (ed.), Synodicon, 33; Assemani, Bibliotheca Orientalis, 2.458; Ḥaddād (ed.), Mukhtaṣar, 125. The fourth/tenth-century historian ʿAmr b. Mattā reports a catholicos going to Basra in the 750s “because its metropolitan had died” (لان مطرانها مات): Henricus Gismondi, Maris Amris et Slibae de Patriarchio Nestorianorum Commentario (2 vols.; Rome: C. de Luigi, 1896), 1.67. For the location of Pěrāth dě-Mayshān, see A. Hausleiter, M. Roaf, St. J. Simpson, R. Wenke (creators), Digital Atlas of Roman and Medieval Civilizations/Harvard University, R. Talbert, P. Flensted Jensen, Jeffrey Becker, Sean Gillies, and Tom Elliott (contributors), “Maghlub/Forat?/Perat de Meshan?/Bahman Ardashir?/‘Oratha’?/Furat al-Baṣra?: A Pleiades Place Resource,” Pleiades: A Gazetteer of Past Places, 2015, and the bibliography cited there. ↑

- See notes 2 and 4 above. ↑

- Robinson, Empire and Elites, 63–72. ↑

- Monastery of Mar Pethyon in Baghdad: Gismondi, De Patriarchio Nestorianorum Commentario, 1.71. ↑

- Ibid., 1.79. ↑

- Ibn Ḥawqal, Ṣūrat al-arḍ, 205; idem, Configuration, trans. Kramer and Wiet, 1.223. ↑

- Hugh Kennedy, “The Feeding of the Five Hundred Thousand: Cities and Agriculture in Early Islamic Mesopotamia,” Iraq 73 (2011): 177–199, 177. ↑

- J. C. Russell, “Late Ancient and Medieval Population,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 48:3 (1958): 1–152, 89, 90. Russell was followed by Bulliet, Conversion to Islam, 80–81. ↑

- Colin McEvedy and Richard Jones, Atlas of World Population History (New York: Penguin Books, 1978), 150–151. ↑

- This report is given by Balādhurī, Futūḥ, 270; idem, Origins, trans. Ḥitti and Murgotten, 1.428. For a discussion of the practice, including the interpretation of this passage, see Chase F. Robinson, “Neck-Sealing in Early Islam,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 48 (2005): 401–441, esp. 414. Presumably reflecting a similar tradition, the round number of five hundred thousand is given, without isnād, by Ibn Ḥawqal, Ṣūrat al-arḍ, 211; idem, Configuration, trans. Kramer and Wiet, 1.227; Muqaddasī, Descriptio, 133; idem, Regions, trans. Collins, 111. Oddly, Muqaddasī specifies this number is “from the foreigners” (من الجوالي), but one might suspect this of a textual corruption from Ibn Ḥawqal’s phrase “people to the jizyah” (انسان للجزية). ↑

- Morony, Iraq after the Muslim Conquest, 175; Balādhurī, Futūḥ, 269; idem, Origins, trans. Ḥitti and Murgotten, 1.427. ↑

- Balādhurī, Futūḥ, 272; idem, Origins, trans. Ḥitti and Murgotten, 1.430. ↑

- Balādhurī, Futūḥ, 266; idem, Origins, trans. Ḥitti and Murgotten, 1.423. ↑

- Balādhurī, Futūḥ, 273–274, 351–353, 359–361, 363–367, 369; idem, Origins, trans. Ḥitti and Murgotten, 1.431–432; 2.69–71, 81–82, 84–85, 88–91, 93–94, 96, 99–100. ↑

- Balādhurī, Futūḥ, 180, 368; idem, Origins, trans. Ḥitti and Murgotten, 1.281; 2.94. ↑

- Balādhurī, Futūḥ, 272–273; idem, Origins, trans. Ḥitti and Murgotten, 1.430–431. Dayr Yazīd (“Yazīd’s monastery”) is likewise mentioned, although with variant names, in two parallel reports included in Abū Yūsuf Yaʿqūb, Kitāb al-Kharāj (Beirut: Dār al-Maʿrifah, 1979), 57. It is not mentioned in any other work I have consulted, so its location and its role in these reports remain elusive. ↑

- Balādhurī, Futūḥ, 265; idem, Origins, trans. Ḥitti and Murgotten, 1.421–422. He later mentioned a dihqān of Maysān who “apostatized and turned away from Islam” (كفر ورجع عن الاسلام) in the caliphate of ʿUmar b. al-Khaṭṭāb, which suggests that he had earlier adopted Islam: Balādhurī, Futūḥ, 343; idem, Origins, trans. Ḥitti and Murgotten, 2.56. Morony cites examples from other sources, and infers that conversion to Islam was general among the first-/seventh-century dahāqīn; Iraq after the Muslim Conquest, 205. ↑

- Balādhurī, Futūḥ, 180; idem, Origins, trans. Ḥitti and Murgotten, 1.281. The comment specifies that these converts, unlike the dahāqīn of the south, were Arabs. ↑

- For example, Balādhurī reported disputed views about the status of al-Sawād: Balādhurī, Futūḥ, 266–268; idem, Origins, trans. Ḥitti and Murgotten, 1.423–426. In the third/late-ninth century, as effective caliphal power waned and the provinces became more autonomous, the tax revenue from Iraq likely played an increasing role in the caliph’s bureaucracy. Iraq’s tax rates and revenues appear prominently in Balādhurī’s discussion of the region; Futūḥ, 268–272, 368; idem, Origins, trans. Ḥitti and Murgotten, 1.426–430; 2.94. ↑

- Morony, Iraq after the Muslim Conquest, 232. ↑

- Balādhurī, Futūḥ, 180; idem, Origins, trans. Ḥitti and Murgotten, 1.281. The prominence of Muslim nomads around Mosul is shown by their taking over the rural tax-collection around 180s/800 (Robinson, Empire and Elites, 96–97). ↑

- Robinson, Empire and Elites, 93, 169. ↑

- Ibn Ḥawqal, Ṣūrat al-arḍ, 196; idem, Configuration, trans. Kramer and Wiet, 1.211. ↑

- Balādhurī, Futūḥ, 293, 351–352, 371–372; idem, Origins, trans. Ḥitti and Murgotten, 1.454; 2.69, 99–100. ↑

- Richard M. Eaton, “Shrines, Cultivators, and Muslim ‘Conversion’ in Punjab and Bengal, 1300-1700,” Medieval History Journal 12 (2009): 191–220, 198–208. ↑

- Muqaddasī, Descriptio, 41; idem, Regions, trans. Collins, 38. ↑

- Muqaddasī, Descriptio, 114–115; idem, Regions, trans. Collins, 95, 97. A village of the same name, evidently closer to al-Madāʾin and Baghdad, is mentioned by Ibn Ḥawqal, Ṣūrat al-arḍ, 219; idem, Configuration, trans. Kramer and Wiet, 1.238. ↑

- Apart from six district capitals, thirteen town mosques are mentioned, whereas his initial listing of towns included eighty-three towns, of which he described twenty-eight more particularly. He also described a few towns which did not make his initial list, such as al-Ṣalīq and Ṣarṣar: Muqaddasī, Descriptio, 119, 121; idem, Regions, trans. Collins, 99, 101. ↑

- Muqaddasī, Descriptio, 130; idem, Regions, trans. Collins,109. For discussions of shrines in Syria shared among Muslims, Christians, and Jews, see Josef W. Meri, The Cult of Saints among Muslims and Jews in Medieval Syria (Oxford University Press, 2002), 195–201, 210–212, 243–250; Carlson, “Contours of Conversion,” 800–802. ↑

- Muqaddasī, Descriptio, 130; idem, Regions, trans. Collins, 109. Ibn Ḥawqal also knew of the tomb of ʿAbd Allāh b. Mubarak at Hīt on the Euphrates; Ṣūrat al-arḍ, 205; idem, Configuration, trans. Kramer and Wiet, 1.222. ↑

- Muqaddasī, Descriptio, 130; idem, Regions, trans. Collins, 109. ↑

- Muqaddasī, Descriptio, 126. Possibly “its pact” (dhimmatuhu) refers to people by metonymy. The translation is adjusted from that of Muqaddasī, Regions, trans. Collins, 105. A textual variant reported by de Goeje would say that most of its dhimmi population was Jewish and Christian (i.e., more than Zoroastrians). ↑

- This is even more significant given that Muqaddasī had complained about his native Jerusalem that Jews and Christians outnumbered Muslims there; Descriptio, 167; idem, Regions, trans. Collins, 141. For him to think Iraq had a noteworthy presence of both these religions, alongside the more distinctive Zoroastrians, is telling. ↑

- For the use of “monastery books” as evidence for Christian-Muslim relations, see Hilary Kilpatrick, “Representations of Social Intercourse between Muslims and non-Muslims in some Medieval Adab Works,” in Jacques Waardenburg (ed.), Muslim Perceptions of Other Religions: A Historical Survey (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 213–224; eadem, “Monasteries Through Muslim Eyes: The Diyārāt Books,” in David Thomas (ed.), Christians at the Heart of Islamic Rule (Leiden: Brill, 2003), 19–37; Thomas Sizgorich, “The Dancing Martyr: Violence, Identity, and the Abbasid Postcolonial,” History of Religions 57 (2017): 2–27. ↑

- Kilpatrick, “Representations,” 217. Kilpatrick cites ʿAlī b. Muḥammad al-Shābūshtī, Kitāb al-Diyārāt, ed. Kūrkīs ʿAwwād (2nd ed.; Baghdād: Maktabat al-Muthannā, 1966), 26*, 309. ↑

- Shābūshtī, Kitāb al-Diyārāt, 3–190, 228–240, 244–283, 300–303, 305–308. ↑

- A century earlier than Shābushtī, the Christian author Īshōʿdnaḥ of Basra composed a biographical dictionary of monastic founders of the Sasanian and early Islamic periods; see Sebastian P. Brock, “Ishoʿdnaḥ,” in Sebastian P. Brock, Aaron M. Butts, George A. Kiraz, and Lucas Van Rompay (eds.), Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage (Piscataway, N.J.: Gorgias, 2011), s.v. The biographies are somewhat muddled chronologically, but at least one explicitly indicates a post-Sasanian foundation of several monasteries by Gabriel of Kashkar (d. 121/739): Jean Baptiste Chabot, “Livre de la Chasteté, composé par Jesusdenah, Évêque de al-Baṣra,” Mélanges d’archéologie et d’histoire 16 (1896): 62, 276. It is also remarkable that Īshōʿdnaḥ, in the middle of the third/ninth century, did not feel the need to mention any Muslims in his text except al-Mutawakkil (once), the “kingdom of the sons of Hāshim” (ܡܠܟܘܬܐ ܕܒܢ̈ܝ ܗܫܡ), and a child slave converted by his successive owners from Zoroastrianism to Islam to Christianity in the second/eighth century: ibid., 30, 64–65, 66, 250, 278, 279. ↑

- Churches would provide a closer analogy to mosques, of course, but there might well be significant divergences even between the number of people who attend a particular church or a particular mosque. In any case, the evidence for a comparison between churches and mosques is lacking, since no early medieval text of which I am aware lists church buildings in Iraq. ↑

- Īshōʿdnaḥ’s work also included references to two ruined monasteries (out of over a hundred): Chabot, “Livre de la Chasteté,” 29, 62, 250, 276. ↑

- For example, Shābūshtī, Kitāb al-Diyārāt, 79. ↑

- The fact that the lists are independent of each other is suggested by the fact that they do not overlap in terminology for bishoprics or metropolitanates, and even when they contain the same places, they often refer to them by different names and in different orders. There is no basis for concluding any textual interrelationship. ↑

- The 410 Syriac list was published with French translation in Chabot (ed.), Synodicon, 33–34, 272–273. Ilyās b. ʿUbayd al-Dimashqī’s Arabic list was published with Latin translation in Assemani, Bibliotheca Orientalis, 2:458–459. The anonymous Arabic list of the fifth/early-eleventh century was published in Ḥaddād (ed.), Mukhtaṣar, 122–130. For more information on the Mukhtaṣar, see Herman Teule, “L’abrégé de la chronique ecclésiastique (Muḫtaṣār [sic] al-aḫbār al-bīʿiyya) et la chronique de Séert. Quelques sondages,” in Muriel Debié (ed.), Historiographie syriaque (Paris: Geuthner, 2009), 161–177; Philip Wood, The Chronicle of Seert: Christian Historical Imagination in Late Antique Iraq (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 70–71. ↑

- Sometimes a bishopric was created even where there were few local Christians of the relevant denomination, for symbolic reasons (as in Jerusalem) or political access (such as the new Eastern Syriac bishop of Damascus); see Fiey, Oriens Christianus novus, 72. ↑

- His reasoning appeals to the general potential for such lists to be out-of-date, the lack of historians’ references to bishops, and the inference that “it is doubtful whether there were many Christians left after two and a half centuries of Muslim rule”; David Wilmshurst, The Martyred Church: A History of the Church of the East (London: East & West, 2011), 161, 163. This last intuition, however, is precisely the question under investigation in this article, and therefore cannot be considered evidence in favor of Wilmshurst’s conclusion. His former two reasons are likewise questionable, as discussed below. ↑

- The most accessible digest of this information is given by Fiey, Oriens Christianus novus. Regrettably, that volume did not include footnotes for individual bishops but only general references for each diocese. In most cases, precise references can be found in J. M. Fiey, Assyrie chrétienne, contribution á l’étude de l’histoire et de la géographie ecclésiastiques et monastiques du nord de l’Iraq (Recherches publiées sous la direction de l’Institut de lettres orientales de Beyrouth 22–23, 42; Beirut: Imprimerie Catholique, 1965–1968). ↑

- Ḥaddād (ed.), Mukhtaṣar, 129. Fiey dates the note to the last scribe of the manuscript, writing in 1137, presumably because he thought he had identified a metropolitan of Armenia between 1075 and 1080: Fiey, Oriens Christianus novus, 59. But there was no catholicos named Yuḥannā between 1075 and 1137, the latest being Yuḥannā VII (r. 442–449/1050–1057). ↑

- Ḥaddād (ed.), Mukhtaṣar, 123. ↑

- Gismondi, De Patriarchio Nestorianorum Commentario, 1.104. Wilmshurst erroneously reversed the direction of the transfer, and on the basis of his misunderstanding he condemned Ilyās b. ʿUbayd’s accuracy; Martyred, 163, 217. Wilmshurst’s discussion of ʿAmr b. Mattā’s history also relies upon an older and erroneous view of its authorship, which had been exposed by Bo Holmberg, “A Reconsideration of the Kitāb Al-Mağdal,” Parole de l’Orient 18 (1993): 255–273. ↑

- Assemani, Bibliotheca Orientalis, 2.458. The editor transcribed the place-name al-Bawāzīkh instead of al-Bawāzīj. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ḥaddād (ed.), Mukhtaṣar, 123; Fiey, Oriens Christianus novus, 62. ↑

- Chabot (ed.), Synodicon, 33–34. ↑

- Ibid., 34. The last four names in the list are not mentioned in Fiey, Oriens Christianus novus. ↑

- Fiey, Oriens Christianus novus, 86–87, 115–116. ↑

- Assemani, Bibliotheca Orientalis, 2.458. See also Fiey, Oriens Christianus novus, 78–79. ↑

- Ḥaddād (ed.), Mukhtaṣar, 125. ↑

- Chabot (ed.), Synodicon, 33. The last is alternately spelled Radaḥ on the following page. ↑

- Assemani, Bibliotheca Orientalis, 2.458. The editor mis-transcribed Shahrqart as Shahrqadt. ↑

- Gismondi, De Patriarchio Nestorianorum Commentario, 1.70. ↑

- Ḥaddād (ed.), Mukhtaṣar, 125. The fact that Daqūqā was listed separately by both Ilyās and the Mukhtaṣar questions Fiey’s assertion that Daqūqā was the residence of the metropolitan of Beth Garmay from ca. 280s/900 onward: Fiey, Oriens Christianus novus, 72. ↑

- Assemani, Bibliotheca Orientalis, 2.458. ↑

- Ḥaddād (ed.), Mukhtaṣar, 123. The diocese of ʿAbdāsī is perhaps to be identified with the otherwise unknown diocese of al-Qubbah, which the Mukhtaṣar notes had recently been merged with the diocese of Kashkar. Fiey provides no identification for al-Qubbah, but suggests that ʿAbdāsī was the continuation of the former diocese of Nahargūr in the metropolitanate of Basra further south: Fiey, Oriens Christianus novus, 43, 114. ↑

- Chabot (ed.), Synodicon, 33. ↑

- Assemani, Bibliotheca Orientalis, 2.458. Assemani misread Dastumaysān as Dastihsan. The identifications are those of Fiey, who suggested that Nahargūr was renamed ʿAbdasī and attached to the province of the catholicos: Fiey, Oriens Christianus novus, 43, 100, 114, 125–126. Even if Fiey’s identification of Nahargūr with ʿAbdasī is correct, as we have seen, it disappeared before 390/1000. ↑

- Ḥaddād (ed.), Mukhtaṣar, 125. ↑

- Older scholarship has made far too much hay out of a theoretical canonical permission for Eastern Syriac bishops to marry. See, for example, Peter Bruns, “Barsauma von Nisibis und die Aufhebung der Klerikerenthaltsamkeit im Gefolge der Synode von Beth-Lapat (484),” Annuarium Historiae Conciliorum 37 (2005): 1–43. In fact, in the medieval millennium, no bishops seem to have done so. ↑