PDF

Download

Citations

Click and drag then release to select a passage to cite.

Annotations

How to submit annotations to Mizan Journal articles:

your work is published.

Search within

Salvation and Suffering in Ottoman Stories of the Prophets

Image

Audio

Video

Chart or Graph

Salvation and Suffering in Ottoman Stories of the Prophets

Introduction: salvation history and stories of the prophets

The Islamic genre of the stories of the prophets (qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ) derives from narrative exegesis of the various references to biblical and Arabian prophets in the Qurʾān. As is well known, the Qurʾān mentions biblical and non-biblical prophets in many instances, but only in exceptional cases (e.g., Sūrat Yūsuf) does it contain detailed narratives about these figures. The Qurʾān evokes those prophetic predecessors of Muḥammad in order to draw comparisons with his own experience, and to call attention to the fact that those earlier prophets essentially preached the same message of salvation.

Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ narratives fill in the narrative gaps, expanding the allusive references of the Qurʾān into full-fledged stories as collections of moral and mythical tales. Just as the references to the earlier prophets reflect the fundamental situation of public preaching, these expanded stories presumably initially took shape in the process of delivering public sermons to a pious audience, translating the essential teachings of Islam into narrative form.1 The Arabic classics of the genre like the work of Aḥmad b. Muḥammad al-Thaʿlabī (d. 427/1035) and the corpus attributed to Muḥammad b. ʿAbd Allāh al-Kisāʾī (twelfth century or later), as well as the Turkic version by Nāṣiruddīn Rabghūzī (completed 1311) are all chronologically arranged, establishing coherence through the sequence of the prophets.2 Their structure, however, is atomistic, which is to say that each section, conceived and narrated as an exemplum originally in the context of a sermon, can essentially stand on its own. Each of them proves its theological or moral point regardless of a larger chronological context, independent of the sections preceding or following it, and other than chronology, a logical connection between subsequent episodes is often missing.

In this article, I would like to present a different type of deployment of the stories of the prophets, one that emphasizes coherence and builds on the narrative that emerges from the sequence of prophets itself. This narrative, in its trajectory of change from one prophet to the other, the continuity of the message of salvation and redemption, and the reception this message receives from humanity, forms the material of Islamic salvation history as conceived by these authors. I investigate examples of Islamic salvation history found in Ottoman Turkish texts in order to explore the societal function of the stories of the prophets. It is my contention that this function is not in any significant way determined by the historical material itself, but that the genre is almost infinitely malleable vis-à-vis the spiritual and worldly concerns of the pious, embodied by authors and audience.

However, since the term ‘salvation history’ is not well established in Islamic Studies, a brief exposition of its heuristic utility is in order. As a premodern form of interpreting the world through history, salvation history “denotes the apparently meaningful sequence of human-divine relationships or the apparently purposeful sequence of divine actions.”3 Its origins go back to the historical dimension of the Old Testament: “According to the prophets, God is following a plan as he guides human history: history is salvation history, determined by his ‘predestination,’ and as such intelligible as a coherent whole. It shall lead to the messianic kingdom of justice and peace which will encompass all peoples as worshippers of Jahwe.”4 Evidently, such an understanding of history as a series of divine acts can apply not only to Jewish and Christian, but also to Muslim narratives, especially regarding the time from creation to the conclusion and culmination of revelation, the time of the Prophet Muḥammad.

When modern methodical historical inquiry began to probe the eventually inevitable discrepancy between “the immutable word of God v. the empirical data of historical change,”5 Christian theologians became increasingly uncomfortable with the concept of salvation history, to the point where they radically discarded the idea of a congruency of historical and theological truth.6 It became clear that salvation history was not a particular set of events separate from, or to be extracted from, secular history. Instead, in the conclusion of his study of the quest for the historical Abraham, Thompson famously stated: “Salvation history is not an historical account of saving events open to the study of the historian. Salvation history did not happen; it is a literary form which has its own historical context.”7 This literary character then opens the genre, including its Islamic manifestations, up to a literary analysis.

In his pioneering study of the ‘biography’ of the Prophet Muḥammad in its oldest extant texts, John Wansbrough identified three themes as foundational for any kind of salvation history: nomos, the law; numen, the encounter with the divine and the communication of divine words; and ecclesia, the community.8 We will see in the course of this article that these themes carry importance beyond the narrations of the life of Muḥammad in Islamic versions of salvation history, and that they are essential for the sequence of the stories of the prophets in particular.

Suffice to recall here that Ibn Isḥāq’s “Life of Muḥammad,” one of the texts at the core of Wansbrough’s endeavor, had originally been part of a larger history. Its first part, which does not survive as a coherent text, was the Kitāb al-Mubtadaʾ, which narrated the line of prophets from Adam leading up to Muḥammad.9 Wansbrough also formulated a more precise understanding of the relationship between history and theology when he asserted that from the perspective of the believer, the essence of salvation history, and the biography of the Prophet Muḥammad (sīrah) in particular, lies in the “historical reading of theology.” Yet he conceded that for the genre that narrates the subsequent period (maghāzī), the opposite may be more accurate: a “theological reading of history.”10 For the genre at issue here, the stories of the prophets, I suggest that the two perspectives occur side by side: in the most basic form, as exempla, the components of the narratives constitute historicized demonstrations of theological truth, but as manifesting a progression in time, they also demonstrate the theological significance of that history.11

Just as important for our purposes, however, is the second part of Thompson’s statement which emphasizes the significance of context. One of the central points of this article will be to inquire in which contexts stories of the prophets were written or narrated, and in which way these narrations were shaped by, and responded to, the societal concerns of authors, narrators, and audiences. Thompson made the fundamental point that salvation history was about the past only inasmuch as this past held a promise for the future:

The promise itself arises out of an understanding of the present which is attributed to the past and recreates it as meaningful. The expression of this faith finds its condensation in an historical form which sees the past as promise. But this expression is not itself a writing of history, nor is it really about the past, but it is about the present hope. Out of the experience of the present, new possibilities of the past emerge, and these new possibilities are expressed typologically in terms of promise and fulfillment. Reflection on the present as fulfillment recreates the past as promise, which reflection itself becomes promise of a future hope.”12

It is my intention in this article to flesh out this statement, by identifying the hopes and expectations which authors and readers found in the stories of the prophets as a form of salvation history in a specific historical context. I will make the case that the subject matter of prophetic history does not by itself determine the salvific meaning superimposed on this history by different authors. Instead, the texts selected for this article diverge radically from each other in terms of the trajectories they construct, and the hopes they derive from these histories. They show that Islamic thinkers have handled the interpenetration of theology and history, operating with radically different concepts of history and salvation, and constructing their very own promise of a trajectory towards salvation on the basis of the stories of the prophets.

The texts discussed in this article mainly belong to the Ottoman classical and postclassical periods, meaning the sixteenth and seventeenth century, and are written in Turkish.13 I will not restrict myself to texts that conform to the genre of the stories of the prophets as it came into its own in Arabic literature, but will study works from different genres that are clearly informed by it, as they evoke the sequence of the prophets. My main focus will be the sequence of the prophets in Fuẓūlī’s martyrology, Garden of the Felicitous, as an example of a rich and complex theological engagement with history and the human condition. In order to contextualize it, I will first briefly discuss two texts which present an essentially optimistic trajectory of history: Ramaẓānzāde Meḥmed Çelebi’s world history extrapolates a future of stability and prosperity, while Süleymān Çelebi celebrates the birth of the Prophet Muḥammad as the actual realization of salvation. I will then follow with another, more pessimistic text, Veysī’s critique of government as inevitably marred by violence and bloodshed, before turning to Fuẓūlī.

Civilizational perfection as eschatology: Ramaẓānzāde Çelebi

A bureaucrat of the Ottoman classical age, Ramaẓānzāde Meḥmed Çelebi (d. 979/1571) wrote a concise and, in informational terms, highly unoriginal but widely-read world history entitled Lives of the Great Prophets and Reigns of the Noble Caliphs and Deeds of the Ottomans (Siyer-i enbiyā-i ʿiẓām ve aḥvāl-i khulefā-i kirām ve menāqib-i Āl-i ʿOs̱mān), which, as the title suggests, begins with the earliest prophet, Adam, and leads through the biblical and Islamic prophets; then proceeds to the history of the Islamic caliphate to the post-Mongol kingdoms of the Middle East; then ends with the most recent and most perfect dispensation, the Ottoman Empire. In his history of the prophets, which in terms of the overall proportion of the work takes up little more than an extended introduction, Ramaẓānzāde is most likely drawing, directly or indirectly, on the famous universal history of Abū Jaʿfar Muḥammad b. Jarīr al-Ṭabarī (d. 310/923) to construct a narrative of progression at several levels.

Salvation history here is first of all revelation history, the successive perfection of the nomos that proceeds from one prophet to the next, as an ever more perfect form of scripture is revealed, culminating in Muḥammad’s receiving the Qurʾān. This progression is paralleled in material terms by the series of buildings erected by prophets in the place of the Ka’bah, from earliest times to the current building attributed to Abraham. At the same time, the community also undergoes a process of civilizational perfection, as prophets introduce technologies like agriculture (Adam), building houses and mining (Mihlāʾīl, in the fourth generation after Adam), writing (Enoch/Idrīs), or carpentry (Noah).14

Ramaẓānzāde also highlights the role of many prophets as kings, of whom Solomon (Süleymān), the biblical namesake of the sultan of his own time, is the most important. He thus turns the focus back to nomos as the foundation of social order, an order that is, significantly, continued beyond the age of the prophets and the caliphs. There is a distinctly descending arc after the period of the Prophet Muḥammad through the Abbasid caliphs to the Mamluks, whom Ramaẓānzāde treats as kings, but then with the Ottomans there is a new ascent to a perfect restoration, culminating in the reign of Süleymān I (r. 1520–1566). Süleymān fashioned himself as the king of the end of time and messiah, and Ramaẓānzāde certainly was aware of this eschatological dimension of Ottoman imperial ideology, which may implicitly underpin his placement of the Ottomans in salvation history.15

In explicit terms, however, Ramaẓānzāde remains more conventional. While his eulogies on Süleymān frequently play with the notion of God’s shadow, thus evoking an old trope for the caliph, this title appears more as an afterthought.16 Praise for the sultan as a poet (which Süleymān I clearly was) allows the historian to use the sultan’s writing poetry (naẓm, lit. “ordering,” i.e., of words) as a metaphor for ordering the world (niẓām). Thus, continuity between the series of prophets and the series of kings after them is furnished by the law, which was constituted through the former and is implemented by the latter. Salvation history in this case records an experience of legal statehood as civilization, the promise of which is reconstructed through the series of prophets, and (in a most optimistic move) projected forward as promise of a legal framework of communal order established or restored with divine approval, which was visible to everyone in the Ottoman victories over infidels and heretics.

Light as grace: Süleymān Çelebi

The actual event of revelation, the theme of numen (in Wansbrough’s terminology), barely figures in Ramaẓānzāde’s account. It does, however, appear in other genres that take up narratives of the prophets, where it is frequently expressed in the imagery of light.

In the discourse of revelation and salvation, light is a primordial substance from which the Prophet Muḥammad was fashioned prior to creation. A light indicative of prophethood also appeared, according to widely narrated legends based on ḥadīth, on the forehead of prophets, and was passed on from generation to generation (since all prophets form one unified tree of descent).17 This light finally appeared on the forehead of ʿAbd Allāh, the father of Muḥammad; then on that of Muḥammad’s mother once she was pregnant with him; and finally on that of the newborn Muḥammad, continuing to shine there throughout his life.18

In this form, the light myth is, for instance, narrated in the opening section of a popular Egyptian sīrah attributed to an elusive author named Abū’l-Ḥasan al-Bakrī (twelfth century?)—popular both in the sense that it was very widely known and beloved, and in the sense that it appealed to the taste of the wider population (in fact, prominent medieval scholars railed against what they saw as superstitions and inaccuracies in this work, but were not able to stop its dissemination).19 This work was translated and much expanded by a blind poet named Muṣṭafā Ḍarīr at the court of the Mamluk Sultan Barqūq (r. 1382–1389 and 1390–1399), to become the earliest narrative of sīrah in Anatolian Turkish.20

In this and similar manifestations of the light myth, it is striking that the light does not symbolize the revelation sent to every prophet, as might be assumed, but rather another phenomenon that complements, or even eclipses, the revelation. As the prophetic light makes the bearer an “enlightened” or charismatic figure, the vessel of a numinous presence, the verbalized divine truth as nomos becomes secondary, and the immediate contact with, and subsequently the veneration of, the bearer of the light emerges as the true way to salvation. The event of the prophetic mission to humanity takes precedence over the content of the mission, and embracing the messenger in specific cultic settings assures salvation. In fact, it does so in even safer ways than complete submission to the legal order established by the prophet would do, since human nature is too weak to ever achieve perfect obedience to the law, meaning that in principle, every human is a sinner and deserves damnation.21

Salvation history in this form narrates the trajectory of the salvific light until it becomes fully and definitely manifest in the person of Muḥammad as redeemer. This is the message, in the Ottoman context, of one the most popular Turkish literary works of all time, Süleymān Çelebi’s poem celebrating the birth of Muḥammad, officially entitled Vesīletü n-necāt (The Means of Salvation), but commonly known simply as Mevlid (from Arabic mawlid, “birth”). Süleymān Çelebi’s poem is dated 1409, almost contemporary with that of Ḍarīr, and probably inspired in part by Ḍarīr’s narrative of the event of Muḥammad’s birth. It stands at the beginning of an almost immeasurably vast Ottoman mevlid literature, as it circulated in thousands of copies and variants, to the point where reconstruction of an “original” is futile. It also gave rise to hundreds of imitations, contrafactions,22 and rewritings, from the fifteenth to the twentieth century.23

No matter what the details of individual works may be, the entire genre in Turkish is predicated on delivering the promise of salvation by means of an extremely condensed form of salvation history, which proceeds through the following essential stages: creation of the Prophet Muḥammad as first act of all creation; the transmission of the prophetic light through the lineage of the prophets from Adam to Muḥammad; Muḥammad’s birth; Muḥammad’s ascension to heaven (the miʿrāj, the actual culmination of his prophethood in the encounter with the divine); and Muḥammad’s final illness and death.24 Like Ramaẓānzāde’s account of communal history, the individualized message for the lovers of the Prophet is essentially optimistic, because it holds out a promise of salvation that is manifested in a few key events, one that is practically impossible to miss because it requires nothing but love for the Prophet, which is the most natural emotion possible given his perfection and his rank with God.25

Struggling with violence and injustice: Veysī

I would like to use the rest of this article to discuss the other side of the coin, that is, versions of salvation history that negate the optimism, serenity, and joy that pervade the examples discussed so far. A profound ambivalence about the moral perils of political power was part of Ottoman elite culture from early on.26 Glorification of conquests and victories on the battlefield was juxtaposed with constant concerns about the impossibility of justice and the inevitability of violence. Skepticism about the possibility of justice in this world is a leitmotif in the mirror-for-princes genre, which in the Ottoman context primarily draw on Persianate models going back to the Seljuq period (eleventh and twelfth centuries). The rejection of state violence is most palpable in the reactions of observers to the violent succession struggles in the Ottoman dynasty enshrined in the so-called “Law of Fratricide,” which legitimized the killing of rival contenders for the throne by the victorious successor.27

Still, even in this well-established discourse of skepticism, the scathing denouncement of worldly power by the poet, stylist, and jurist Üveys b. Meḥmed (d. 1037/1628), known as Veysī, stands out. In the vast Ottoman literature of political advice, Veysī’s Dream Book (Ḫābnāme) is unusual due to its format, style, and moral rigor.28 Where most advice books, or mirrors-for-princes, deal with the problems of the imperial household and various state institutions, Veysī framed his critique and advice as a (fictitious) dream narrative in which he saw the sultan of the time, Aḥmed I (r. 1603–1617), to whom the work is also dedicated, in conversation with Alexander the Great (Iskandar Dhū’l-Qarnayn or İskender), who in Islamic literature and mythology embodies the idealized combination of prophetic inspiration and imperial rule.29

Veysī claims that he had wanted to confront the sultan with his grievances about the lack of order, and then had this dream—an elegant twist to avoid faulting the sultan for problems, while giving him moral advice. When Aḥmed complains to him about the trouble of governing justly in a disrupted world order, Alexander responds by asking: “When has that world that you say is in ruins today ever been populous and prosperous (maʿmūr ve abādān)?” He then enumerates to Aḥmed dozens of historical examples from Adam to the present, each culminating in the same rhetorical question, driving home the point that the world order that according to Aḥmed had been lost (incidentally, the same order that Ramāẓānzāde had extolled) never really existed.30 Instead, the sultan, and by extension Veysī, hears from Alexander that the human experience in the world has never been anything but oppression and suffering.

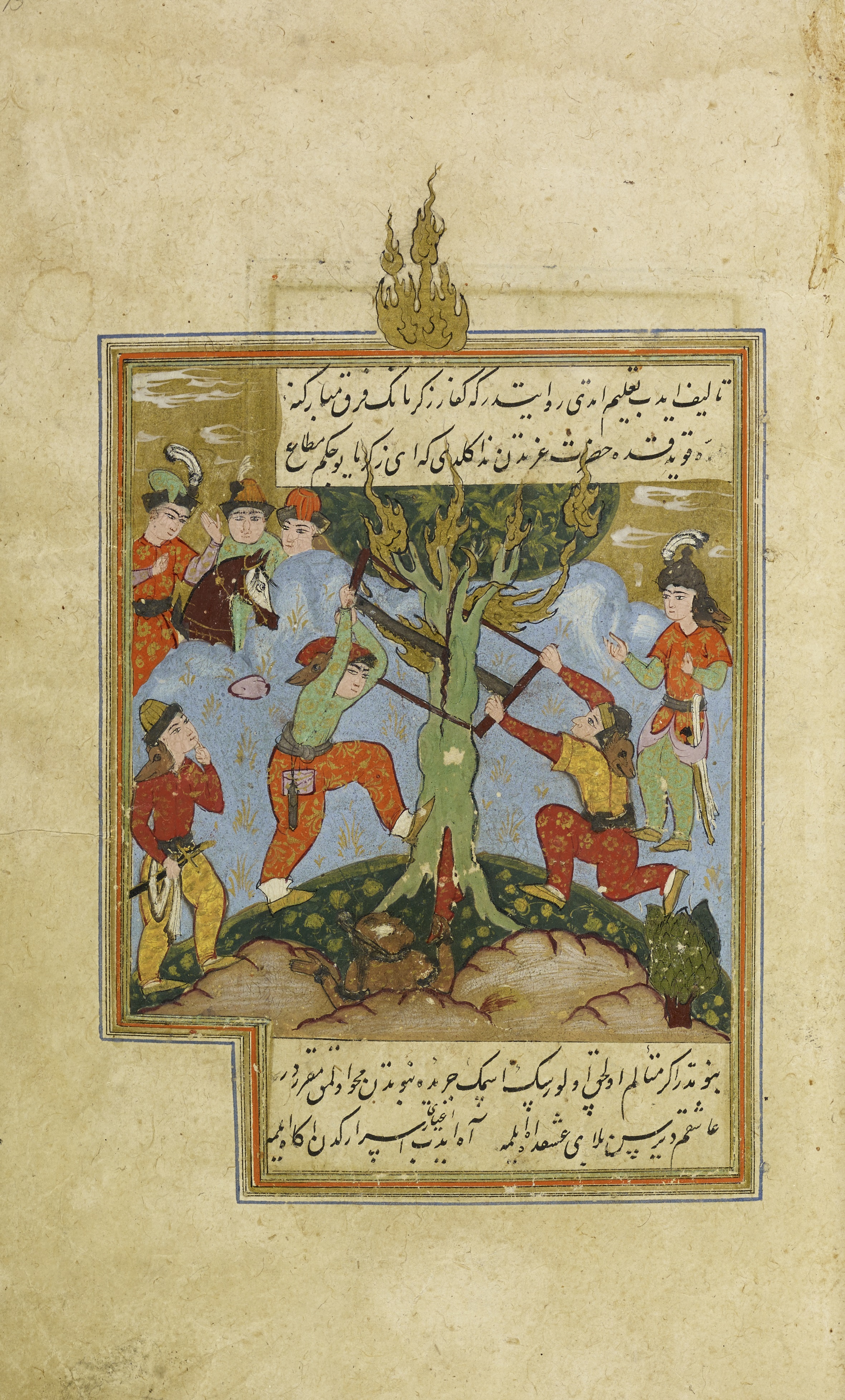

What is interesting for our topic is that some of the perennial misery Alexander summons happened under the watch of prophets, such as the flood of Noah, which killed innumerable people. In other cases, violence targeted prophets like Abraham, who was persecuted by Nimrod (Nimrūd) and thrown into a blazing fire, or Zechariah (Zakariyāʾ), who hid in a hollow tree trunk when fleeing persecution and ended up being sawed in half when his hiding place was discovered and cut down (see Gallery Image A). Other prophets also became victims of violence of unbelievers and tyrants; the humiliation Muḥammad experienced at the hand of the pagan Meccans is well known. In Veysī’s brief (and highly selective) retelling, prophets suffer, like all human beings, from violence caused by human greed and weakness. This suffering begins with Cain’s (Qābil) murder of his brother Abel (Hābil), which functions in this history almost like an “original sin,” indicating that it is caused by man, and keeping man in his place to maintain social order is what the sultan is concerned about. By contrast, the suffering of Job (Ayyūb), which, as we know also from the Bible, was caused by Satan, is of little relevance for Veysī’s inverted salvation history. Moreover, different from our last example below, suffering is indisputably evil, and lacks, as told here, any potential to reform the sufferer, and thus any redemptive meaning.

The benign order established through the law and upheld by caliphs and sultans in Ramaẓānzāde’s history all but vanishes here, leaving the individual powerless and victimized, while the sultan—and this is the final point in Veysī’s treatise—has no choice but to try to dispense justice as best as he can, knowing that he will fail most of the time. This means that the theme of salvation history is present largely in negated form, because the history told is not driven by divine intervention, but by human decisions; history is not a record of communal progression towards salvation, but rather the arena in which the individual (and the sultan in particular) tries to win salvation, with only slim chance of success.

Sufi and Shi’i poetics in Ottoman Iraq: Fuẓūlī

In contrast to the human fallibility that causes the crises and suffering addressed by Veysī, in the last and most complex example to be discussed in this article, the suffering of prophets and believers is first and foremost ordained by God. This example takes us to yet another genre, the martyrology, which commemorates the martyrdom of al-Ḥusayn b. Abī Ṭālib, grandson of the Prophet Muḥammad, the third imām of Shi’i Islam, in the battle of Karbalāʾ on the tenth of Muḥarram of the Muslim year 61 (680 CE). Throughout the Shi’i parts of the Islamic world, rituals of commemoration and mourning for the Imām are held on this day, called ʿĀshūrāʾ, also recognized as a day of fasting by some Sunnis since the time of the Prophet. Besides processions and the staging of passion plays, the recitation of poems or narratives plays an important part in these events, such that a typical martyrology (often called maqtal, “killing,” i.e., of Ḥusayn) is divided into ten chapters, to be recited during the ten days of Muḥarram leading up to the commemoration of the catastrophe.31 The death of Ḥusayn at Karbalāʾ is nothing less than the cosmic, axial event of Shi’i salvation history, as Mahmoud Ayoub has shown in his pioneering study, to which we will return below.

The martyrology I wish to focus on for this article is Fuẓūlī’s Garden of the Felicitous (Ḥadīqatü s-suʿadā), by the poet Muḥammad b. Sulaymān, known as Fuẓūlī (d. 963/1556), an Iraqi of Turkmen descent, widely admired as one of the luminaries of classical Ottoman poetry, and a perfect exemplar of the cosmopolitan literary and religious culture which Shahab Ahmed has described as the “Balkans-to-Bengal Complex.”32 The work in question is a free translation or re-rendering of a work by Wāʿiẓ-i Kāshifī (d. 910/1504), who wrote in Persian under the patronage of the Timurid sultan of Herat.33 Both works consist of ten chapters, the first of which recounts the sufferings of the earlier prophets, and the second the humiliations and violence against Muḥammad from his tribe, the Quraysh.34 Kāshifī’s Meadows of the Felicitous (Rawẓatu s-suʿadāʾ) betrays his eloquence as well as his erudition, although it is free of the technical trappings of Islamic scholarship, and Fuẓūlī maintained those characteristics in his translation.

Fuẓūlī, who wrote poetry in Arabic and Persian besides Turkish (with a distinct regional inflection), spent all his life in Iraq—in Baghdad, where he saw the region’s conquest by the Ottomans under Süleymān I in 1534; in Najaf, where he served at the shrine of ʿAlī; and in Karbalāʾ, where he died in 1556. He thus inhabited a geography shaped by a strong Shi’i presence, most importantly the shrines of Najaf and Karbalāʾ, where the martyred imāms of Shi’i Islam were buried and are venerated to this day.

Since our main interest is in ideas and texts circulating in Ottoman society, Fuẓūlī’s dependence on earlier models and supposed lack of originality should not concern us. At the same time, his influence is hard to overstate. Hundreds of manuscripts and several printed editions of the Garden of the Felicitous exist, attesting to unbroken success from the time of the author onward into the twentieth century. It is noteworthy that his Shi’i context and his own possible inclinations did not prevent the author from seeking patronage from the Ottoman sultan, who was at that time fashioning himself as the champion of Sunni Islam.35 The veneration of the family and descendants of Muḥammad, including ʿAlī, Ḥasan, Ḥusayn, that is, the ahl al-bayt, is shared across sectarian boundaries, which explains why historians have not found a conclusive way of identifying Fuẓūlī (or his predecessor Kāshifī, for that matter) as unambiguously Shi’ite.36

All this should caution us as modern readers not to project sectarian boundaries between Sunnis and Shi’ites back uncritically; while such a divide mattered politically between the Ottomans and Safavid Iran, Fuẓūlī’s case demonstrates that it mattered less in the search for a particular type of religiosity in which suffering takes on central significance. This religiosity cuts across the legal and doctrinal distinctions which are maintained in the analytical and argumentative discourse of Islamic scholarship.37 Instead, Fuẓūlī, like Kāshifī, chose the evocative and associative language of poetry to capture the experiential, emotional dimension of the event of Karbalāʾ; the fact that many manuscript copies are illustrated equally speaks to this aspect.38

Poetry is, after all, the primary language of the mystic, and the religiosity in point here can arguably be called mystical because it is so centered on an emotional (and specifically, tragic and horrifying) experience that is not accessible to rational discourse. In Ottoman classical literature, which was heavily informed by Persianate models, poetic language does more than expand the emotional range of expression; it enables the author to establish semantic connections intra- and intertextually through a canonical repertoire of metaphors, and to insert a layer of meanings which are not explicitly articulated in the text, but evident to the educated reader.39 Fuẓūlī was a master of this technique, which he used to the fullest account in a praise poem for the Prophet Muḥammad that is known as the Water Ode (Ṣu Qaṣīdesi).

In this poem, Fuẓūlī ran through every variant of the metaphors of water and fire to express his burning desire for the Prophet, but the unspoken subtext, never mentioned explicitly, is the battle of Karbalāʾ, where the believers under Ḥusayn were cut off from water and suffered thirst for several days, until the last survivors surrendered.40 For our text, we may look at the way Fuẓūlī deployed the metaphor of the rose to describe the prophet Joseph, which may appear obvious given Joseph’s physical beauty. But there is more: Joseph’s pleas with his brothers “open the rose of compassion in Judah”; later the bloody stains of his shirt presented to his father are rose-colored. As he escapes the pursuit of Pharaoh’s wife Zulaikha, Joseph’s torn garment is compared to the crack in the rose-bud through which the petals become visible; the image of the rose in the garden captures both his status among his brothers and at the court of Pharaoh. At the same time, no Ottoman reader worth his salt would have missed the fact that the rose is a favorite symbol for the Prophet Muḥammad.41 It pertains to him because of his beauty, but also because its scent compares to the spread of the divine message; there is also an immediate connection between the rose and the figure of the cup-bearer who serves the intoxicating drink of divine love. None other than Fuẓūlī has mustered every possible variant of the rose metaphor in an ode to Sultan Süleymān, known as the Rose Ode (Gül Qaṣīdesi).42 Thus, the metaphor serves to suggest here an essential likeness between Joseph and Muḥammad that is at the core of his work. In another instance, his treacherous brothers threw Joseph, who was “the crown jewel of their felicity, into the dust of humiliation like a turban is thrown down in an act of mourning.”43 Here the image not only poignantly illustrates the outrageous injustice and humiliation done to Joseph, but the image of the turban in the dust also evokes the mourning incumbent on the faithful reader in commemorating Joseph and the martyrs of Karbalāʾ.

Joseph, Muḥammad, and the theology of affliction in Fuẓūlī

Fuẓūlī consistently describes this world as the ‘House of Sorrows’ (bayt al-aḥzān), a term that resonates widely in Shi’ite pious literature.44 Another favorite term is ‘Prison of Affliction’ (zindān-i belā); Joseph uses it for the pit into which his brothers threw him, but it also stands for the world at large, indicating the inescapable and violent nature of suffering, which affects every pious person in this world.45 This suffering becomes the yardstick of righteousness, as in the saying “greater affliction is the result of deeper devotion” (aʿẓam al-balāʾ maʿa aʿẓam al-walāʾ).46 Affliction brings out devotion in the way in which fire purifies gold (al-balāʾ li’l-walāʾ ka’l-lahab li’l-dhahab), and the plant of fidelity in the garden of earthly existence flourishes under the rain of affliction.47

Fuẓūlī opens his work with an exegesis of Q Baqarah 2:155–156: “Surely We will try you with something of fear and hunger, and diminution of goods and lives and fruits; yet give thou good tidings unto the patient, who, when they are visited by an affliction, say, ‘Surely we belong to God, and to Him we return.’”48 Based on this verse, Fuẓūlī develops a kind of typology of afflictions, to include fear of this and other-worldly punishment; physical deprivation through ascetic exercises or as result of need; material poverty as result of war; physical decline due to age or illness; and also, under the category of ‘fruits,’ deprivation of offspring.49 It is noteworthy that all these kinds of suffering relate to the body, and to social contexts, but do not include afflictions of doubt or spiritual struggles of the kind familiar in Christian hagiography from Augustine onwards. Physical pain and oppression by the powers that be are the most important categories of suffering that appear throughout Fuẓūlī’s account of the earlier prophets in his first two chapters: persecution by infidel kings (Pharaoh, Nimrod), captivity, hunger, thirst, and eventually death, but also rejection by the community (Job, Muḥammad) are most prominent; poverty becomes a prominent theme in the life of Fāṭimah in the last chapter.50 The most severe of them, however, is the death of offspring, an affliction that has an obvious emotional side, but also a social aspect, since offspring assures a man’s standing in society. This is the affliction that links Jacob to Muḥammad.51

As is well known, the “Story of Joseph” (qiṣṣat yūsuf) is the only extensive narrative about a biblical prophet in the Qurʾān, where it forms the twelfth sūrah. It comes to no surprise, therefore, that this narrative is also by far the most detailed in the Garden of the Felicitous, but it is remarkable that it is framed as the “Story of Jacob,” i.e., Joseph’s father, rather than that of Joseph himself. Fuẓūlī opens this section with an anecdote about Muḥammad, who is joyfully watching his two grandchildren, Ḥasan and Ḥusayn, at play. This idyllic scene of familial bliss is interrupted by the appearance of the angel Gabriel, who first inquires about Muḥammad’s love for the children, and, when he has ascertained that he loves both equally, informs him that both will die a violent death, one from poison, the other in battle. Moreover, both will die, pure and innocent, at the hands of Muḥammad’s unfaithful community (ümmet-i bī-vefā). Seeing Muḥammad’s despair at this terrible news, Gabriel reveals Sūrah 12, which begins “We will relate to thee the fairest of stories” (Q 12:3), as a consolation, to demonstrate that Muḥammad is not the only prophet to suffer in this way, that is, to be deprived of his offspring.

Thus, different from what the genre of martyrology and the focus on the drama of Karbalāʾ may suggest, the suffering narrated here is not so much that of Joseph, or of Ḥasan and Ḥusayn, but rather that of their father or grandfather respectively. This shift of focus may appear cruel or cynical to the modern reader, but needs to be taken seriously in the context of the social logic of premodern societies. It remains to be investigated if this shift from the imāms as the actual martyrs back to Muḥammad as the target also implies a subtle form of de-Shi’itization of the genre, given the fact that Shi’ite Islam has often been accused of giving greater importance to ʿAlī and the imāms than to the Prophet himself. In any case, Fuẓūlī never oversteps the boundaries of Sunni doctrine; he explicitly states that Muḥammad is the most noble messenger exactly because he suffered from the Quraysh and from the lowly ones of his community what no other prophet has ever suffered.52

Suffering and salvation history

The connection which is thus established between Muḥammad and one of the previous prophets illuminates the concept of salvation history in the logic of Fuẓūlī’s (and probably Kāshifī’s) martyrologies. Ayoub remarks:

Before Karbalāʾ, from Adam onward, the prophets are said to have participated in the sorrows of Muḥammad and his vicegerents, and especially in the martyrdom of his grandson, Ḥusayn, in two ways. Each was told of it, and thus shared in the grief of the Holy Family; and in a small way, directly or indirectly, each tasted some of the pain or sorrow that is associated with the sacred spot of Karbalāʾ.53

In fact, beyond the poetic connections made through the shared metaphors, as discussed above, Fuẓūlī comments in multiple instances how the experience of a prophet foreshadows the cosmic catastrophe that is Karbalāʾ. Reminders are always present, e.g., the ark of Noah shakes when it passes over the spot of Karbalāʾ. When Joseph is tortured by his brothers, and they pour the drink his father has given them for him on the ground to mock him, Fuẓūlī remarks: “Just the same way, at Karbalāʾ some damned ones diverted the fresh water of the Euphrates, which was licit to all creation, away from the family of the Prophet, and while the path of right guidance was obvious, they went down the road of error.”54 In his despair, Joseph prays to God for help, invoking how Abraham was rescued from the fire of Nimrod and Noah escaped the flood.

In short, throughout the stories of the prophets as narrated in this work, author and protagonists refer to both earlier and later examples. In the quote above, Ayoub suggests that there was foreknowledge of Karbalāʾ among the earlier prophets. He also quotes a ḥadīth that identifies a period of corruption in the history of mankind, beginning with the martyrdom of Abel and ending with the martyrdom of Ḥusayn.55 In putting it this way, Ayoub still assumes a history that develops towards, and culminates in, Karbalāʾ, although he cautions that “sacred history belongs not to material or calendar time.”56 I have given only a minuscule fraction of Fuẓūlī’s weaving together of images and incidents, yet they should suffice to support my argument that he goes further than such a sacred history: Fuẓūlī collapses all events of salvation history into one another, so that they all become one, present at all times and everywhere—that is, Karbalāʾ.

There is, of course, an external chronology in the events Fuẓūlī narrates, but there is no past or future in any meaningful sense in the significance of the events. Muḥammad receives a “true report” (ḫaber-i vāqiʿ) of Ḥusayn’s martyrdom—as if it had already happened.57 This obsolescence of chronological time in God’s knowledge was, as Erich Auerbach pointed out, fully developed by Augustine: “What does foreknowledge mean if not the knowledge of things to come? What are things to come to God who transcends all times?”58 From here Auerbach developed the concept of “figura” which suggests that in the salvation history of late antique and medieval Christianity, an event or person can prefigure another, and while they remain distinct, the former receives its full meaning from the fact that it will achieve fulfillment only in the latter. In our case, then, every instance in Fuẓūlī’s salvation history, every suffering of an earlier prophet ‘prefigures’ Karbalāʾ, such that the resulting sense of time conforms to what was, which Auerbach characterizes as “omnitemporality” (Jederzeitlichkeit).59

History thus occurs between prefiguration and fulfillment, but the prefigured event is always already present in the prefiguration; in other words, history is nothing but the path to the external manifestation. Arguably, then, there is no history as an account of actual change, only one of actualization. The suffering inflicted on the prophets and on the pious is an ontological condition, as expressed in the example of Adam, who was created from clay “kneaded with the water of pain and grief.”60 This condition is not subject to change, although God may vary the degrees, as he did in the story of Job, who experienced multiple calamities over time. Needless to say, there is no factor of human choice, as all this ‘history’ is divinely preordained. To what degree Karbalāʾ is the axial event of salvation history can be gleaned from the fact that the apocalypse is mentioned primarily as the instance where the martyrs are avenged by the Messiah.61

If there is no history in this Fuẓūlīan version of salvation history, is there salvation? If we think of salvation in the Christian sense, as used in the original sense of salvation history, then the answer should be no. The theme of Fuẓūlī’s martyrology is not an eschatological event of salvation beyond the chronology of history; by the same token, the cosmic catastrophe of Karbalāʾ is not the transformative event of redemption in the way the death of Christ on the cross atones for the original sin according to Christian theology. Ayoub entitled his pioneering study Redemptive Suffering, but despite his resort to biblical terminology, he distinguishes the concept from a Christian interpretation: “Redemption is used here in the broadest sense to mean the healing of existence or the fulfillment of human life… This fulfillment through suffering is what this study will call redemption.”62

Ayoub’s statement that “suffering… must be regarded as an evil power of negation and destruction” seems to resonate with the fact that at one point in Fuẓūlī’s work, it is explained as divine punishment. In the opening of the section on Jacob, the author briefly entertains the idea that Jacob was afflicted as he was because when he let his beloved son Joseph depart, he commended him to his oldest brother rather than to God, an obvious breach of the concept of trust in God (tevekkül).63 More generally, however, the suffering of the prophets is, as stated before, a measure of their proximity to God; moreover, it is a sign of God’s love (maḥabbet) for his servants, from the prophets through the saints down to the ordinary believers. In Sufi thought, with which Fuẓūlī is mostly aligned, this is because of the good things it teaches humanity, and the blessings that the sufferer receives as alleviation, and because of the reward received for patience.64

Because it originates from God, as a sign of his love, the true believer should not wish to end their suffering, but rather to embrace it and to perpetuate it. The model is Abraham, who actually wished to sacrifice his son, not in order to demonstrate his obedience to God’s command, but in order to share in the grief of Muḥammad over the martyrs of Karbalāʾ.65 Fuẓūlī has God declare that “the reward for your grief over the innocent victim of Karbalāʾ is greater than that for your sacrificing your son.”66 This last statement, then, extends the logic of embracing suffering from the prophets to the ordinary believer, and at the same time explains the purpose of Fuẓūlī’s text. If the sharing of grief over the martyred imām is the most sublime form of suffering, then the ideal form in which to do so is the commemoration through rituals of mourning and the performance of texts like Fuẓūlī’s, in pious gatherings or as individual reading.67 This way, at one level, the individual follows the example of the saints and prophets, but also atones for being part of the “faithless community” (ümmet-i bī-vefā) that is guilty of all the cruelty against the prophets. Their guilt is manifest in Fāṭimah’s appearance at the gathering of the souls on Judgment Day, donning the insignia of her murdered sons Ḥasan and Ḥusayn. But the Prophet will instead ask her to intercede on behalf of those in the community who have shed tears on behalf of the martyrs of Karbalāʾ.68

Redemption thus does not lie in overcoming suffering, just as the effect of the narrative is not intended to be cathartic: rather it lies in the conscious immersion in perpetual awareness of its origins and its meaning as a sign of unchanging divine love, and yet, somewhat paradoxically, in this same immersion lies the hope of the believer for salvation in the hereafter.69 The suffering of the prophets thus leads to a new answer to the question of theodicy as posed by the mystics; as behooves a mystic, among whom we have counted Fuẓūlī, the response is not grounded in theological and philosophical reasoning, but points to practices of devotion and piety. These devotional practices are not individual ones, obviously, but to be performed together, as the foundation of a community united in suffering. Of the three themes of salvation history identified by Wansbrough, which we quoted at the beginning, it is the theme of ecclesia that is most salient in these stories.70

Conclusion

What, then, can the examples given in this article tell us about the function of stories of the prophets as Islamic salvation histories? We have seen how all four Ottoman authors we have discussed here deal with the material provided by the classical collections (and other sources) in a rather selective manner, to arrive at rather diverging ways to make these stories meaningful. While all of these texts were received and disseminated by the elite of the empire, taken together, they paint a complex picture of engagement with the world that is far from homogenous, and is not simply determined by the sociopolitical context of the Ottoman Empire at large. All authors construct specific dynamics across history. These may be progressions towards a perfect social order, or the assurance of salvation through divine grace expressed in the mission of the Muḥammadan light, or, by contrast, the cycles of human greed and folly ever repeating themselves in the struggle for power, or, in our last example, the presence of suffering as an essential aspect of the human condition, which cannot be overcome, but rather can only be embraced.

The reader may have noticed that in their selective treatment of the material, Veysī and Fuẓūlī in particular barely ever mention the essential events of prophethood, that is, the revelation of the various scriptures. It would be foolish, however, to assume that these events did not matter for them. Both wrote for a highly educated audience, and could easily take the essential facts of revelation history, together with knowledge of scripture and essentials of exegesis, for granted. All the texts examined here are part of a literary system, contributing to and drawing from a broader discourse about “God, world, and man,” and cannot be understood in isolation.71 While they are all part of Ottoman literature, they cannot be construed as a collective articulation of Ottoman imperial ideology. Nor can each of their distinct ideas, their specific interpretations of the stories of the prophets, easily be mapped onto specific periods of history or specific social and intellectual groups.

Although the search for imperial patronage may have motivated Fuẓūlī or Ramaẓānzāde, authors’ relationships to political power appear conflicted and contradictory, to the point where the political is either ignored (by Süleymān Çelebi) or rejected (by Veysī, at least at first glance). It may be true that Ramaẓānzāde’s history reflects the view of history of the time with its teleology towards a sultan-messiah. Veysī’s trenchant critique of Ottoman politics clearly targets his own time, although this critique resonated, probably with different nuances, for many generations after. Süleymān Çelebi’s promise of salvation may have originated early in the fifteenth century, but it was meaningful to the pious for centuries, offering them hope and joy in their lives.

In the same way, Fuẓūlī may have initially written the Garden of the Felicitous in order to seek the patronage of the Ottoman sultans, and make the Ottoman elite aware of the sacred landscape of newly conquered Iraq with its shrines of the imāms. This same work, however, also resonated with thousands of later readers because it was able to provide them with meaning for their own experience in life. For instance, it almost achieved the rank of a sacred text among the Bektashi dervishes, who cultivated, often rightly so, a self-image of the systematically oppressed by a majoritarian Sunni orthodoxy.72 Which hardship, injustice, or deprivation it was that these Bektashis and other readers brought to the text is impossible to say, but it is safe to suggest that Fuẓūlī helped them to relate the stories of the prophets to their own experiences in life, while they may, in other situations, have resorted to the Mevlid, or thought about contemporary politics with Veysī and Ramaẓānzāde. Thus, the promises for the future, of which Thompson spoke as the deeper concern of salvation history, could be exceedingly different, not only because experiences were different, but because the pious were able to see different purposes and different meanings in them.

Ottoman society was never homogenous, but neither were its numerous subcultures neatly separated from one another; rather than a mosaic consisting of discrete monochromatic stones, the watercolor—with its blending and the relativity of contrast and hue—may be the more appropriate metaphor for its intellectual and religious life. Ottoman culture deserves to be appreciated in its entirety and complexity. Rather than seeking to neatly isolate specific subgroups with their ideas and ideologies, historians should embrace the challenge posed by their mixture and the resulting frequent contradictions, an element that is, as Shahab Ahmed has so aptly demonstrated, “essentially” Islamic, but also simply (though not trivially) human.73

About the author

Gottfried Hagen teaches Ottoman history, language, and culture at the University of Michigan. He received his M.A. in Islamic Studies from the University of Heidelberg, and his Ph.D. in Turkish Studies from Freie Universität Berlin. His research focuses on Ottoman and Islamic engagement with the empirical world through interpretation and representation. As such he studies many literary genres such as hagiography, historiography, cosmography, travelogues, and biographies of the Prophet Muḥammad. His publications include a monograph on the polymath Kātib Çelebi, many articles and book chapters, and contributions to reference works like the Cambridge History of Turkey, the Encyclopaedia of Islam, and others.

Notes

1 Marc Vandamme, “Rabghuzi’s Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyā’, Reconsidered in the Light of Western Medieval Studies: Narrationes Vel Exempla,” in Hendrik Boeschoten (ed.), De Turcicis Aliisque Rebus. Commentarii Henry Hofman dedicati (Utrecht: Instituut voor Oosterse Talen en Culturen, 1992); Roberto Tottoli, Biblical Prophets in the Qur’an and Muslim Literature (Richmond: Curzon, 2002); Tilman Nagel, “Die Qiṣaṣ Al-Anbiyāʾ: Ein Beitrag zur Arabischen Literaturgeschichte” (Ph.D. dissertation, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, 1967).

2 Marianna Klar, Interpreting al-Tha’labī’s Tales of the Prophets: Temptation, Responsibility and Loss (London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2009); Muḥammad b. ʿAbd Allāh al-Kisāʾī, Tales of the Prophets, trans. Wheeler M. Thackston (Chicago: Kazi, 1997 [1978]); Nosiruddin al-Rabghūzī, The Stories of the Prophets: Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ: An Eastern Turkish Version, ed. H. E. Boeschoten, M. Vandamme, and S. Tezcan (Leiden: Brill, 1995).

3 Alfons Weiser, “Heilsgeschichte I. Biblisch-theologisch,” Lexikon für Theologie und Kirche (3rd ed.; Freiburg: Herder, 1993–2001), s.v. (1995).

4 Michael Landmann, “Geschichte/Geschichtsschreibung/Geschichtsphilosophie X: Geschichtsphilosophie,” Theologische Realenzyklopädie (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1976–2004), s.v. (1984).

5 John Wansbrough, The Sectarian Milieu: Content and Composition of Islamic Salvation History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978), 140.

6 Friedrich Mildenberger, “Salvation History,” Religion Past and Present, 2011.

7 Thomas L. Thompson, The Historicity of the Patriarchal Narratives: The Quest for the Historical Abraham (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1974), 328, as quoted by Andrew Rippin, “Literary Analysis of Qur’ān, Tafsīr, and Sīra. The Methodologies of John Wansbrough,” in Richard C. Martin (ed.), Approaches to Islam in Religious Studies (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1985), 151–163, 155.

8 Wansbrough, Sectarian Milieu, 131.

9 See the reconstruction attempt by Gordon D. Newby, The Making of the Last Prophet: A Reconstruction of the Earliest Biography of Muḥammad (Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press, 1989), and the fierce criticism by Lawrence I. Conrad, “Recovering Lost Texts: Some Methodological Issues. Review of: The Making of the Last Prophet: A Reconstruction of the Earliest Biography of Muḥammad by Gordon Darnell Newby,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 113 (1993), 258–263.

10 Wansbrough, Sectarian Milieu, 148f. An analogous convergence of biblical narrative and history was not a given in Christian contexts either, but occurred in the Middle Ages, especially from the twelfth century onwards; Odilo Engels, “Geschichte III. Begriffsverständnis im Mittelalter,” Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe. Historisches Lexikon zur politisch-sozialen Sprache in Deutschland (Studienausgabe, Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, 2004), s.v.

11 See also Gottfried Hagen, “From Haggadic Exegesis to Myth: Popular Stories of the Prophets in Islam,” in Roberta Sabbath (ed.), Sacred Tropes: Tanakh, New Testament and Qur’an as Literature and Culture (Leiden: Brill, 2009), 301–316.

12 Thompson, The Historicity of the Patriarchal Narratives, 329.

13 I am using the term ‘Ottoman Turkish’ for the literary language that was constitutive of the Ottoman elite, and ‘Anatolian Turkish’ for the branch of Turkish used in Asia Minor, of which Ottoman is a special subset.

14 Meḥmed Pasha Ramaẓānzāde, Siyer-i enbiyā-i ʿiẓām ve aḥvāl-i khulefā-i kirām ve menāqib-i Āl-i ʿOs̱mān (Constantinople: Ṭabʿḫāne-i ʿĀmire, 1279 [1862–1863]), 13–22; see also Hagen, “From Haggadic Exegesis to Myth: Popular Stories of the Prophets in Islam,” 309.

15 Cornell Fleischer, “Mahdi and Millennium: Messianic Dimensions in the Development of Ottoman Imperial Ideology,” in Kemal Çiçek (ed.), The Great Ottoman Turkish Civilization (Ankara: Yeni Türkiye Yayınları, 2000), 42–54.

16 Ramaẓānzāde, Siyer-i enbiyā-i ʿiẓām, 229.

17 Authors who deployed the light myth did not seem overly concerned with the break between Jesus as the penultimate and Muḥammad as the last prophet.

18 These essential elements of the light myth have been masterfully studied, together with several others, by Uri Rubin, “Pre-Existence and Light: Aspects of the Nūr Muḥammad,” Israel Oriental Studies 5 (1975): 62–119. On light in the Qurʾān, see also Jamal J. Elias, “Light,” Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān (Leiden: Brill, 2001), s.v.

19 Boaz Shoshan, Popular Culture in Medieval Cairo (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 23–24.

20 Gottfried Hagen, “Some Considerations about the Terǧüme-i Darir ve taqdimetü z-zahir, based on Manuscripts in German Libraries,” Journal of Turkish Studies/Türklük Bilgisi Araştırmaları 26 (2002): 323–337. The illustrated manuscript of this text produced for the Ottoman Sultan Murād III (r. 1576–95) is famous: see Zeren Tanındı, Siyer-i nebî: İslâm tasvir sanatında Hz. Muhammed’in hayatı (n.p. [Istanbul?]: Hürriyet Vakfı Yayınları, 1984); Christiane Gruber, “Between Logos (Kalima) and Light (Nūr): Representation of the Prophet Muhammad in Islamic Painting,” Muqarnas 26 (2009): 229–262. On Ḍarīr’s main source, Abū’l-Ḥasan al-Bakrī, see Shoshan, Popular Culture in Medieval Cairo, 23–39.

21 See the rigid demand for obedience expressed in works like Qāḍī ʿIyāḍ al-Yakhṣubī’s Al-Shifāʾ, as studied by Tilman Nagel, Allahs Liebling. Ursprung und Erscheinungsformen des Mohammedglaubens (München: Oldenbourg Verlag, 2008), 144–192.

22 Arab and Ottoman poets wrote contrafactions (Turkish naẓīre, Arabic muʿāraḍah) on prominent poems, by using the same rhyme, meter, and imagery as the original, both as a token of admiration, and as poetic one-upmanship. For a prominent example and a detailed analysis of the technique, see Suzanne Stetkevych, The Mantle Odes: Arabic Praise Poems to the Prophet Muhammad (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010), 151–157 and passim.

23 Gottfried Hagen, “Mawlid, Ottoman,” in Coeli Fitzpatrick and Adam H. Walker (eds.), Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God (Santa Barbara: ABC Clio, 2014), 369–373, with earlier literature.

24 I am following here the earliest and still most authoritative critical edition, Ahmed Ateş, Süleyman Çelebi: Vesîletü’n-necât (Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu, 1954). Many manuscripts supplement the core as summarized here with additional narratives about the death of Muḥammad’s family members and legends about the efficacy of the love for the prophet. For the genre in Arabic as distinct from the Turkish, see Marion Holmes Katz, The Birth of the Prophet Muḥammad: Devotional Piety in Sunni Islam (London: Routledge, 2007).

25 For a sense how Süleymān Çelebi’s work came to function within the Ottoman literary system as an omnipresent and universal reflection of Ottoman religiosity, see Hüseyin Vassâf’s massive early twentieth-century commentary: Hüseyin Vassâf, Mevlid Şerhi. Gülzâr-ı Aşk, ed. Mustafa Tatçı, Musa Yıldız, and Kaplan Üstüner (Istanbul: Dergâh Yayınları, 2006).

26 Modern neo-Ottoman nationalism in its idolization of state power has all but erased this ambivalence.

27 See Nicolas Vatin and Gilles Veinstein, Le Sérail ébranlé. Essai sur les morts, dépositions et avènements des sultans ottomans (XIVe-XIXe siècle) (Paris: Fayard, 2003), 149–170.

28 The Ḫābnāme was printed in Ottoman script several times. I am basing my account on the modern transliteration: Üveys b. Meḥmed Veysī, Hâb-nâme-i Veysî, ed. Mustafa Altun (Istanbul: MVT, 2011).

29 On the origins of the Alexander narrative in the Qurʾān (Sūrat al-Kahf) and the literary elaborations of the Alexander Romance in Islam, see A. Abel, “Iskandar Nāma,” Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.; Leiden: Brill, 1954–2005), s.v.

30 In having Alexander survey all of history, Veysī mirrors an older work called the Book of Alexander (İskender-nāme) by Aḥmedī (d. 815/1412); see Dimitris J. Kastritsis, “The Alexander Romance and the Rise of the Ottoman Empire,” in A. C. S. Peacock and Sara Nur Yıldız (eds.), Islamic Literature and Intellectual Life in Fourteenth- and Fifteenth-Century Anatolia (Würzburg: Ergon, 2016), 243–286.

31 See Şeyma Güngör, “Maktel-i Hüseyin,” in Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslam Ansiklopedisi (Istanbul: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı, 1988–2013), s.v., and the seminal study of Mahmoud M. Ayoub, Redemptive Suffering in Islam: A Study of the Devotional Aspects of Ashura in Twelver Shi’ism (Hamburg: De Gruyter, 1978). Sabrina Mervin speaks of a “Karbalāʾ paradigm” in “ʿĀshūrāʾ Rituals, Identity and Politics: A Comparative Approach (Lebanon and India),” in Farhad Daftary and Gurdofarid Miskinzoda (eds.), The Study of Shi’i Islam: History, Theology, and Law (London: I. B. Tauris, 2014), 507–528. To be sure, maqtal literature exists in Sunni contexts as well.

32 Shahab Ahmed, What Is Islam? The Importance of Being Islamic (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015).

33 On Wāʿiẓ-i Kāshifī, see Abbas Amanat, “Meadow of the Martyrs: Kāshifī’s Persianization of the Shīʿī Martyrdom Narratives in the Late Timurid Herat,” in Farhad Daftary and Joseph W. Meri (eds.), Culture and Memory in Medieval Islam: Essays in Honour of Wilferd Madelung (London: I. B. Tauris, 2003), 250–275.

34 Chapters 3 through 6 are dedicated to the deaths of Muḥammad, Fāṭimah, ʿAlī, and Ḥusayn’s brother al-Ḥasan respectively, while the rest of the work narrates in much detail the events leading up to Karbalāʾ and finally the martyrdom of the imām itself. Multiple printed editions are available. I am citing the critical edition by Şeyma Güngör, Hadikatü’s Süeda. Fuzulî (Ankara: Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı, 1987).

35 Halil İnalcık, Şâir ve Patron. Patrimonyal Devlet ve Sanat Üzerinde Sosyolojik Bir İnceleme (Ankara: Doğu Batı, 2003).

36 Derin Terzioğlu, referencing Claude Cahen, speaks of a late medieval “Shiitization of Sunni Islam” in “How to Conceptualize Ottoman Sunnitization: A Historiographical Discussion,” Turcica 44 (2013): 301–338, 307. Amanat, “Meadows of the Martyrs,” suggests that the Shi’i Kāshifī practiced dissimulation (taqiyyah) in Sunni Herat, but as Kāshifī was serving Sunni patrons and married into a staunchly anti-Shi’i Sufi lineage, the question arises what significance “being actually Shi’i” would retain.

37 For an Ottoman example, see Nabil al-Tikriti, “Kalam in the Service of State: Apostasy Rulings and the Defining of Ottoman Communal Identity,” in Hakan T. Karateke and Maurus Reinkowski (eds.), Legitimizing the Order: Ottoman Rhetoric of State Power (Leiden: Brill, 2005), 131–149.

38 Rachel Milstein, Miniature Painting in Ottoman Baghdad (Costa Mesa: Mazda Publishers, 1990); Rachel Milstein, Karin Rührdanz, and Barbara Schmitz, Stories of the Prophets: Illustrated Manuscripts of Qiṣaṣ al-Anbiyāʾ (Costa Mesa: Mazda, 1999).

39 My understanding of Ottoman poetics is strongly informed by the work of Walter Andrews, especially Poetry’s Voice, Society’s Song: Ottoman Lyric Poetry (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1985). İhsan Fazlıoğlu demonstrates the need for close attention to the philosophical dimension of Fuẓūlī’s poetry as well: Fuzulî ne demek istedi? Işk imiş her ne var Âlem’de / İlm bir kıl kîl u kâl imiş ancak (Istanbul: Papersense, 2014).

40 For a concise commentary, see Mustafa Kara, Metinlerle Osmanlılarda Tasavvuf ve Tarikatlar (Bursa: Sır Yayıncılık, 2004), 160–167, and in more detail, Ahmet Attilâ Şentürk, Osmanlı Şiiri Antolojisi (Istanbul: Yapı Kredi Yayınları, 2011), 239–275.

41 Annemarie Schimmel, And Muhammad Is His Messenger: The Veneration of the Prophet in Islamic Piety (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1985), 24–55.

42 Şentürk, Osmanlı Şiiri Antolojisi, 275–292. Joseph is mentioned in verses 8–9, and Muḥammad, whose heart opens under the breath of Gabriel like the rosebud in the wind of spring, in verse 10. Verses 1 and 9 are quoted in Fuẓūlī, Ḥadīqatu s-suʿadā, 47.

43 Fuẓūlī, Ḥadīqatu s-suʿadā, 50.

44 Ayoub, Redemptive Suffering, 23–52.

45 Fuẓūlī, Ḥadīqatu s-suʿadā, 55.

46 Fuẓūlī, Ḥadīqatu s-suʿadā, 52.

47 Fuẓūlī, Ḥadīqatu s-suʿadā, 11.

48 Arberry’s translation.

49 Fuẓūlī, Ḥadīqatu s-suʿadā, 9–10.

50 On Fāṭimah’s significance as ‘Mistress of the House of Sorrows,’ see Ayoub, Redemptive Suffering. Ayoub mentions other examples of poverty in the household of the Prophet (37ff), but they are missing in Fuẓūlī’s work.

51 The motif returns with Zechariah’s realization that his son John will be killed, just like he himself will be killed (Fuẓūlī, Ḥadīqatu s-suʿadā, 75).

52 Fuẓūlī, Ḥadīqatu s-suʿadā, 13.

53 Ayoub, Redemptive Suffering, 27. It is worth noting that neither Jacob nor Joseph is mentioned among his examples.

54 Fuẓūlī, Ḥadīqatu s-suʿadā, 51, as one example out of many. Note, as another example of the multiple layers of meaning in Fuẓūlī’s poetic language, the parallel between the natural course of the river and the path of righteousness.

55 Ayoub, Redemptive Suffering, 27.

56 Ibid., 28.

57 Fuẓūlī, Ḥadīqatu s-suʿadā, 52.

58“Quid enim est praescientia nisi scientia futurorum? Quid autem futurum est Deo qui omnia supergreditur tempora?” in Erich Auerbach, “Figura,” in idem, Gesammelte Aufsätze zur romanischen Philologie (Bern: Francke, 1967), 71.

59 Erich Auerbach, Mimesis. Dargestellte Wirklichkeit in der abendländischen Literatur (Bern: Francke, 1959), 188–192; published in English as Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature, trans. Willard R. Trask (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1953). Omnitemporality is to be distinguished from extratemporality (Überzeitlichkeit). Auerbach distinguishes this typology from allegory and symbolism, because it leaves both figure and fulfillment in place as historical realities. See his “Typological Symbolism in Medieval Literature,” in idem, Gesammelte Aufsätze, 111.

60 Fuẓūlī, Ḥadīqatu s-suʿadā, 19.

61 Fuẓūlī, Ḥadīqatu s-suʿadā, 80–81.

62 Ayoub, Redemptive Suffering, 23.

63 Fuẓūlī, Ḥadīqatu s-suʿadā, 49.

64 Hellmut Ritter, The Ocean of the Soul: Man, the World, and God in the Stories of Farīd al-Dīn ʿAṭṭār (Leiden: Brill, 2003), 239–245. The loss of relatives is specifically mentioned (241ff.)

65 Ayoub, Redemptive Suffering, 32. Zechariah on the other hand is reminded by God to stop complaining of the pain of being sawed in half if he does not want to lose his status as prophet: Fuẓūlī, Ḥadīqatu s-suʿadā, 79.

66 Fuẓūlī, Ḥadīqatu s-suʿadā, 42.

67 The poetic quality of Fuẓūlī’s and Kāshifī’s works lends itself to public recitation, as Amanat documents for Kāshifī’s work.

68 Fuẓūlī, Ḥadīqatu s-suʿadā, 78.

69 Navid Kermani argues that Shi’i passion plays, which function analogously (theologically speaking), do have a cathartic effect; to what degree this is the intention of the genre remains an open question. See “The Truth of Theatre,” in idem, Between Quran and Kafka. West-Eastern Affinities (Cambridge: Polity, 2016), 106–127.

70 Wansbrough, Sectarian Milieu, 131.

71 I am borrowing these terms from the apt title of Ritter’s book, above.

72 John Kingsley Birge, The Bektaşi Order of Dervishes (London: Luzac & Co., 1937), 169.

73 Ahmed, What is Islam?

Salvation and Suffering in Ottoman Stories of the Prophets

Introduction: salvation history and stories of the prophets

The Islamic genre of the stories of the prophets (qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ) derives from narrative exegesis of the various references to biblical and Arabian prophets in the Qurʾān. As is well known, the Qurʾān mentions biblical and non-biblical prophets in many instances, but only in exceptional cases (e.g., Sūrat Yūsuf) does it contain detailed narratives about these figures. The Qurʾān evokes those prophetic predecessors of Muḥammad in order to draw comparisons with his own experience, and to call attention to the fact that those earlier prophets essentially preached the same message of salvation.

Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ narratives fill in the narrative gaps, expanding the allusive references of the Qurʾān into full-fledged stories as collections of moral and mythical tales. Just as the references to the earlier prophets reflect the fundamental situation of public preaching, these expanded stories presumably initially took shape in the process of delivering public sermons to a pious audience, translating the essential teachings of Islam into narrative form.1 The Arabic classics of the genre like the work of Aḥmad b. Muḥammad al-Thaʿlabī (d. 427/1035) and the corpus attributed to Muḥammad b. ʿAbd Allāh al-Kisāʾī (twelfth century or later), as well as the Turkic version by Nāṣiruddīn Rabghūzī (completed 1311) are all chronologically arranged, establishing coherence through the sequence of the prophets.2 Their structure, however, is atomistic, which is to say that each section, conceived and narrated as an exemplum originally in the context of a sermon, can essentially stand on its own. Each of them proves its theological or moral point regardless of a larger chronological context, independent of the sections preceding or following it, and other than chronology, a logical connection between subsequent episodes is often missing.

In this article, I would like to present a different type of deployment of the stories of the prophets, one that emphasizes coherence and builds on the narrative that emerges from the sequence of prophets itself. This narrative, in its trajectory of change from one prophet to the other, the continuity of the message of salvation and redemption, and the reception this message receives from humanity, forms the material of Islamic salvation history as conceived by these authors. I investigate examples of Islamic salvation history found in Ottoman Turkish texts in order to explore the societal function of the stories of the prophets. It is my contention that this function is not in any significant way determined by the historical material itself, but that the genre is almost infinitely malleable vis-à-vis the spiritual and worldly concerns of the pious, embodied by authors and audience.

However, since the term ‘salvation history’ is not well established in Islamic Studies, a brief exposition of its heuristic utility is in order. As a premodern form of interpreting the world through history, salvation history “denotes the apparently meaningful sequence of human-divine relationships or the apparently purposeful sequence of divine actions.”3 Its origins go back to the historical dimension of the Old Testament: “According to the prophets, God is following a plan as he guides human history: history is salvation history, determined by his ‘predestination,’ and as such intelligible as a coherent whole. It shall lead to the messianic kingdom of justice and peace which will encompass all peoples as worshippers of Jahwe.”4 Evidently, such an understanding of history as a series of divine acts can apply not only to Jewish and Christian, but also to Muslim narratives, especially regarding the time from creation to the conclusion and culmination of revelation, the time of the Prophet Muḥammad.

When modern methodical historical inquiry began to probe the eventually inevitable discrepancy between “the immutable word of God v. the empirical data of historical change,”5 Christian theologians became increasingly uncomfortable with the concept of salvation history, to the point where they radically discarded the idea of a congruency of historical and theological truth.6 It became clear that salvation history was not a particular set of events separate from, or to be extracted from, secular history. Instead, in the conclusion of his study of the quest for the historical Abraham, Thompson famously stated: “Salvation history is not an historical account of saving events open to the study of the historian. Salvation history did not happen; it is a literary form which has its own historical context.”7 This literary character then opens the genre, including its Islamic manifestations, up to a literary analysis.

In his pioneering study of the ‘biography’ of the Prophet Muḥammad in its oldest extant texts, John Wansbrough identified three themes as foundational for any kind of salvation history: nomos, the law; numen, the encounter with the divine and the communication of divine words; and ecclesia, the community.8 We will see in the course of this article that these themes carry importance beyond the narrations of the life of Muḥammad in Islamic versions of salvation history, and that they are essential for the sequence of the stories of the prophets in particular.

Suffice to recall here that Ibn Isḥāq’s “Life of Muḥammad,” one of the texts at the core of Wansbrough’s endeavor, had originally been part of a larger history. Its first part, which does not survive as a coherent text, was the Kitāb al-Mubtadaʾ, which narrated the line of prophets from Adam leading up to Muḥammad.9 Wansbrough also formulated a more precise understanding of the relationship between history and theology when he asserted that from the perspective of the believer, the essence of salvation history, and the biography of the Prophet Muḥammad (sīrah) in particular, lies in the “historical reading of theology.” Yet he conceded that for the genre that narrates the subsequent period (maghāzī), the opposite may be more accurate: a “theological reading of history.”10 For the genre at issue here, the stories of the prophets, I suggest that the two perspectives occur side by side: in the most basic form, as exempla, the components of the narratives constitute historicized demonstrations of theological truth, but as manifesting a progression in time, they also demonstrate the theological significance of that history.11

Just as important for our purposes, however, is the second part of Thompson’s statement which emphasizes the significance of context. One of the central points of this article will be to inquire in which contexts stories of the prophets were written or narrated, and in which way these narrations were shaped by, and responded to, the societal concerns of authors, narrators, and audiences. Thompson made the fundamental point that salvation history was about the past only inasmuch as this past held a promise for the future:

The promise itself arises out of an understanding of the present which is attributed to the past and recreates it as meaningful. The expression of this faith finds its condensation in an historical form which sees the past as promise. But this expression is not itself a writing of history, nor is it really about the past, but it is about the present hope. Out of the experience of the present, new possibilities of the past emerge, and these new possibilities are expressed typologically in terms of promise and fulfillment. Reflection on the present as fulfillment recreates the past as promise, which reflection itself becomes promise of a future hope.”12

It is my intention in this article to flesh out this statement, by identifying the hopes and expectations which authors and readers found in the stories of the prophets as a form of salvation history in a specific historical context. I will make the case that the subject matter of prophetic history does not by itself determine the salvific meaning superimposed on this history by different authors. Instead, the texts selected for this article diverge radically from each other in terms of the trajectories they construct, and the hopes they derive from these histories. They show that Islamic thinkers have handled the interpenetration of theology and history, operating with radically different concepts of history and salvation, and constructing their very own promise of a trajectory towards salvation on the basis of the stories of the prophets.

The texts discussed in this article mainly belong to the Ottoman classical and postclassical periods, meaning the sixteenth and seventeenth century, and are written in Turkish.13 I will not restrict myself to texts that conform to the genre of the stories of the prophets as it came into its own in Arabic literature, but will study works from different genres that are clearly informed by it, as they evoke the sequence of the prophets. My main focus will be the sequence of the prophets in Fuẓūlī’s martyrology, Garden of the Felicitous, as an example of a rich and complex theological engagement with history and the human condition. In order to contextualize it, I will first briefly discuss two texts which present an essentially optimistic trajectory of history: Ramaẓānzāde Meḥmed Çelebi’s world history extrapolates a future of stability and prosperity, while Süleymān Çelebi celebrates the birth of the Prophet Muḥammad as the actual realization of salvation. I will then follow with another, more pessimistic text, Veysī’s critique of government as inevitably marred by violence and bloodshed, before turning to Fuẓūlī.

Civilizational perfection as eschatology: Ramaẓānzāde Çelebi

A bureaucrat of the Ottoman classical age, Ramaẓānzāde Meḥmed Çelebi (d. 979/1571) wrote a concise and, in informational terms, highly unoriginal but widely-read world history entitled Lives of the Great Prophets and Reigns of the Noble Caliphs and Deeds of the Ottomans (Siyer-i enbiyā-i ʿiẓām ve aḥvāl-i khulefā-i kirām ve menāqib-i Āl-i ʿOs̱mān), which, as the title suggests, begins with the earliest prophet, Adam, and leads through the biblical and Islamic prophets; then proceeds to the history of the Islamic caliphate to the post-Mongol kingdoms of the Middle East; then ends with the most recent and most perfect dispensation, the Ottoman Empire. In his history of the prophets, which in terms of the overall proportion of the work takes up little more than an extended introduction, Ramaẓānzāde is most likely drawing, directly or indirectly, on the famous universal history of Abū Jaʿfar Muḥammad b. Jarīr al-Ṭabarī (d. 310/923) to construct a narrative of progression at several levels.

Salvation history here is first of all revelation history, the successive perfection of the nomos that proceeds from one prophet to the next, as an ever more perfect form of scripture is revealed, culminating in Muḥammad’s receiving the Qurʾān. This progression is paralleled in material terms by the series of buildings erected by prophets in the place of the Ka’bah, from earliest times to the current building attributed to Abraham. At the same time, the community also undergoes a process of civilizational perfection, as prophets introduce technologies like agriculture (Adam), building houses and mining (Mihlāʾīl, in the fourth generation after Adam), writing (Enoch/Idrīs), or carpentry (Noah).14

Ramaẓānzāde also highlights the role of many prophets as kings, of whom Solomon (Süleymān), the biblical namesake of the sultan of his own time, is the most important. He thus turns the focus back to nomos as the foundation of social order, an order that is, significantly, continued beyond the age of the prophets and the caliphs. There is a distinctly descending arc after the period of the Prophet Muḥammad through the Abbasid caliphs to the Mamluks, whom Ramaẓānzāde treats as kings, but then with the Ottomans there is a new ascent to a perfect restoration, culminating in the reign of Süleymān I (r. 1520–1566). Süleymān fashioned himself as the king of the end of time and messiah, and Ramaẓānzāde certainly was aware of this eschatological dimension of Ottoman imperial ideology, which may implicitly underpin his placement of the Ottomans in salvation history.15

In explicit terms, however, Ramaẓānzāde remains more conventional. While his eulogies on Süleymān frequently play with the notion of God’s shadow, thus evoking an old trope for the caliph, this title appears more as an afterthought.16 Praise for the sultan as a poet (which Süleymān I clearly was) allows the historian to use the sultan’s writing poetry (naẓm, lit. “ordering,” i.e., of words) as a metaphor for ordering the world (niẓām). Thus, continuity between the series of prophets and the series of kings after them is furnished by the law, which was constituted through the former and is implemented by the latter. Salvation history in this case records an experience of legal statehood as civilization, the promise of which is reconstructed through the series of prophets, and (in a most optimistic move) projected forward as promise of a legal framework of communal order established or restored with divine approval, which was visible to everyone in the Ottoman victories over infidels and heretics.

Light as grace: Süleymān Çelebi

The actual event of revelation, the theme of numen (in Wansbrough’s terminology), barely figures in Ramaẓānzāde’s account. It does, however, appear in other genres that take up narratives of the prophets, where it is frequently expressed in the imagery of light.

In the discourse of revelation and salvation, light is a primordial substance from which the Prophet Muḥammad was fashioned prior to creation. A light indicative of prophethood also appeared, according to widely narrated legends based on ḥadīth, on the forehead of prophets, and was passed on from generation to generation (since all prophets form one unified tree of descent).17 This light finally appeared on the forehead of ʿAbd Allāh, the father of Muḥammad; then on that of Muḥammad’s mother once she was pregnant with him; and finally on that of the newborn Muḥammad, continuing to shine there throughout his life.18