PDF

Download

Citations

Click and drag then release to select a passage to cite.

Annotations

How to submit annotations to Mizan Journal articles:

your work is published.

Search within

“Christian” Paintings in an “Islamic” Palace

A New Reading of the Alhambra’s Ceiling Paintings

“Christian” Paintings in an “Islamic” Palace

A New Reading of the Alhambra’s Ceiling Paintings

The medieval palace of the Alhambra was built in Granada, Spain under the patronage of Muslim Nasrid rulers. Sometime after the Nasrid Muhammad V (r. 1354–1359; 1362–1391) regained the throne in 1362 and before his death in 1391, he apparently had three ceiling bays in the Alhambra painted with figural scenes (Figure 1).1 The three bays are located along one side of the Court of the Lions; the space in which they are located has been identified by some as a madrasa or library. Two of these three ceiling bays represent scenes of romance: knights riding in combat and hunting wild beasts, lovers meeting at a fountain and playing chess, and a wildman, while the third (central) bay represents a group of ten Muslim men. The two romance-themed bays have become well-known as a “problem” in art history: how do we make sense of these paintings, apparently in a Christian style and bearing Christian iconography, in an Islamic palace?2

The denotation of the problem as “Christian” imagery in an “Islamic” palace is of course an oversimplification, driven by contemporary disciplinary divisions. Medieval viewers, especially those accustomed to the hybrid cultures of the Iberian peninsula, would not necessarily have understood the paintings in these terms. It remains, however, to determine what medieval viewers would have understood from all three of the Alhambra’s ceiling bays.

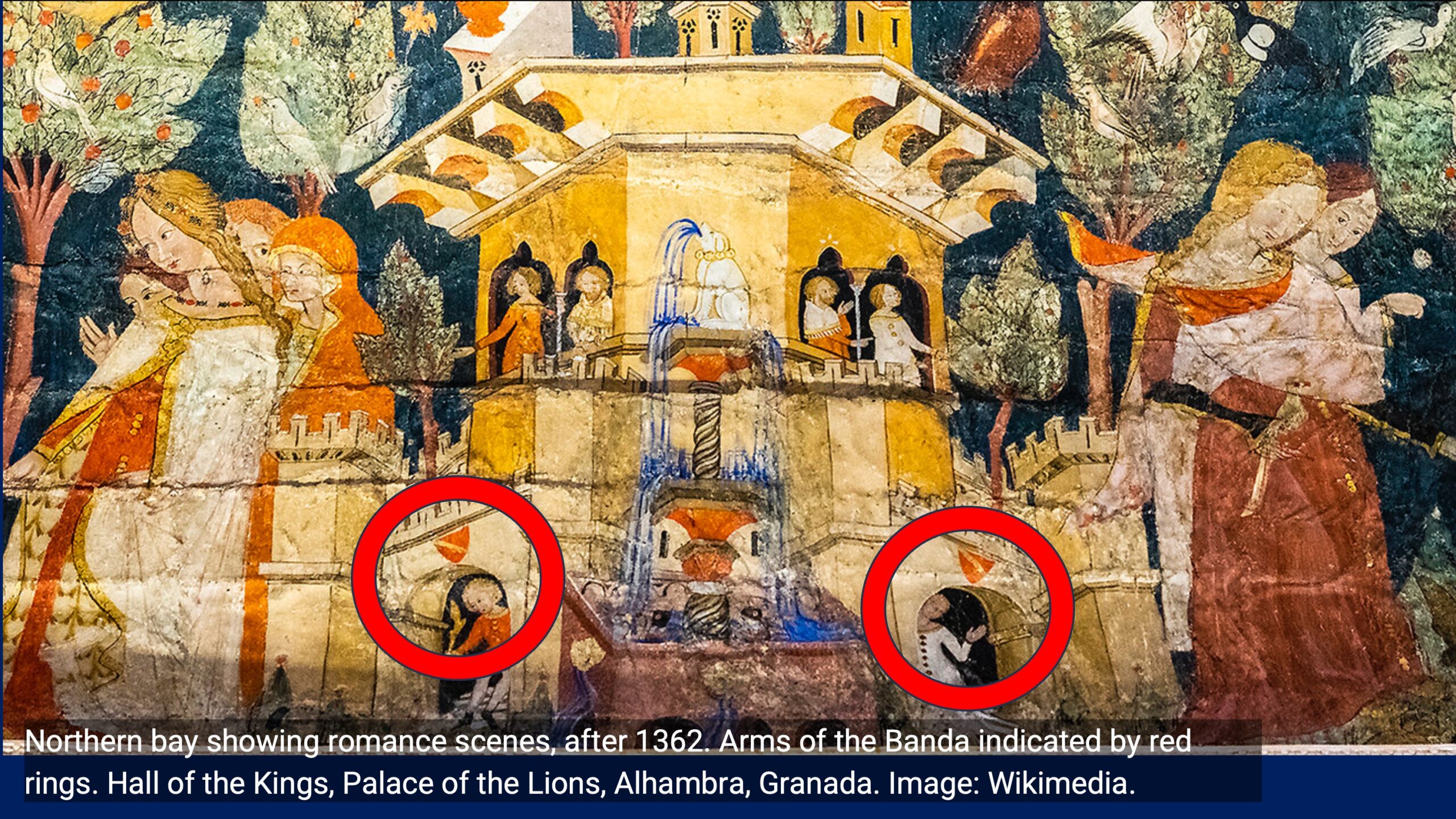

Many attempts have been made to tie specific episodes from the Alhambra’s famous secular figural ceiling paintings to specific literary narratives. Despite the Alhambra’s Nasrid patronage, both the visual and literary connections raised are generally from Christian sources, suggesting the cultural hybridity of the fourteenth-century Iberian peninsula. I suggest that attempting to pin particular motifs to particular narratives is not only – in at least some cases – futile, but also, more importantly, misses the point of the paintings. The aim of these sophisticated paintings was to connect fiction to reality, and reality to fiction: in particular, to illustrate the chivalry of historical members of the Order of the Banda or Scarf by portraying them in the visual forms of widely-recognized protagonists of romance. While the romance paintings suggest secular narratives, in fact they select and display visual motifs for a non-narrative purpose.

The arms of the Order of the Banda are explicitly painted in all three bays, a fact which has been recognized by numerous scholars. However, no one has yet suggested that this chivalric order has a prominent or structuring role within these paintings. Using attention to iconography, color, and composition, I argue that the painted actions, heraldic colors, and repeated inclusion of the coat of arms of the Banda within the paintings are all intended to reference this chivalric order (Figures 2, 3, 4). I maintain that not only can each of the activities included in the side bays (hunts, lovers’ meetings, combats) be read in relation to the written requirements of the Order, but the major colors in the costumes of almost all of the so-called narrative figures are substantially red with gold, the heraldic colors shown here in the arms of the Banda and those used in the Order of the Banda in the later fourteenth century.3 The women in the castle, the man who falls from horseback, the couple at the fountain, the men who beat the bush for game, the knight who spears a boar, the couple playing chess – indeed, nearly every single one of the dozens of figures included in the side bays – are each dressed in colors which are substantially red and gold. One should not discount the fact that red and gold stand out well against the dark foliage; still, orange, turquoise, pink and pale blue would have done so as well. The castles display red roofs, turrets, and shutters, frequently with gold trim; coats of arms showing the Banda are not placed randomly on the castle walls but instead are carefully placed to mark the castle entrances, suggesting their inhabitants’ allegiance to the Banda. Yet today’s scholars, seduced by the challenge of identifying “the narrative,” have repeatedly passed over these and other suggestive visual cues.

The Order of the Banda or Scarf was a chivalric order founded in Christian Castile in 1330.4 It was bestowed both upon Castilians and individuals from various nations whom the Castilian king wished to honor. The emphasis on loyalty within the statutes of the Banda took on a particular historical inflection during the reign of the Castilian king Pedro, who reigned 1350 – 1366 and then again 1367 – 1369. Pedro’s rule was interrupted when his half-brother seized the throne in 1366. Pedro was also known “the Cruel” or “the Just” (depending on your perspective on his serial killings of those who contested his claim for the Castilian throne). The device of the Banda was used during this period as a device signaling that the bearer was a recipient of the favor of the Castilian king.5 Muhammad V was among those who fought to restore the Castilian throne to Pedro. Muhammad V’s loyalty in 1366-37 to Pedro was understandable, as just a few years previously, in 1362, Pedro had invited the usurper of Muhammad V’s throne to Castile and there butchered him, restoring Muhammad V’s rule in Granada.

I suggest that the Alhambra’s figural ceiling paintings depict an intentional collage of scenes drawn from romance, but these paintings were not intended to represent any particular romance. These compositions were assembled instead with another purpose in mind: to refer to a chivalric order, its coat-of-arms, heraldic colors, and prescribed courtly activities. The visual structure of the ceilings, their composition, and color, are powerful reminders that other kinds of content can be just as important as narrative.

Bibliography

Boulton, D. Arcy Jonathan Dacre. The Knights of the Crown: The Monarchical Orders of Knighthood in Later Medieval Europe 1325-1520. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press, 1987.

Dickie, James. “The Palaces of the Alhambra.” In Al-Andalus, the Art of Islamic Spain, edited by Jerrilynn Dodds. 135-51. New York: the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992.

Dodds, Jerrilynn Denise. “The Paintings in the Sala De Justicia of the Alhambra: Iconography and Iconology.” Art Bulletin 61, no. 2 (1979): 186-97.

Robinson, Cynthia, and Simone Pinet, eds. Courting the Alhambra: Cross-Disciplinary Approaches to the Hall of Justice Ceilings. Vol. 14.2-3, Medieval Encounters (Special Issue), 2008.

Notes

1 The precise date of the completion of the ceiling paintings is unknown. James Dickie and others agree that the completion of the Palace of the Lions in the Alhambra took place during the second reign of Muhammad V; that is, 1362-91. James Dickie, “The Palaces of the Alhambra,” in Al-Andalus, the Art of Islamic Spain, ed. Jerrilynn Dodds (New York: the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992), 145.

2 Jerrilynn Denise Dodds, “The Paintings in the Sala de Justicia of the Alhambra: Iconography and Iconology,” Art Bulletin 61, no. 2 (1979): 186-97; Cynthia Robinson and Simone Pinet, eds., Courting the Alhambra: Cross-Disciplinary Approaches to the Hall of Justice Ceilings, vol. 14.2-3, Medieval Encounters (special issue) (2008).

3 D. Arcy Jonathan Dacre Boulton, The Knights of the Crown: the Monarchical Orders of Knighthood in Later Medieval Europe 1325-1520 (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press, 1987), 86-89.

4 Ibid., 52.

5 Ibid., 60.

“Christian” Paintings in an “Islamic” Palace

A New Reading of the Alhambra’s Ceiling Paintings

The medieval palace of the Alhambra was built in Granada, Spain under the patronage of Muslim Nasrid rulers. Sometime after the Nasrid Muhammad V (r. 1354–1359; 1362–1391) regained the throne in 1362 and before his death in 1391, he apparently had three ceiling bays in the Alhambra painted with figural scenes (Figure 1).1 The three bays are located along one side of the Court of the Lions; the space in which they are located has been identified by some as a madrasa or library. Two of these three ceiling bays represent scenes of romance: knights riding in combat and hunting wild beasts, lovers meeting at a fountain and playing chess, and a wildman, while the third (central) bay represents a group of ten Muslim men. The two romance-themed bays have become well-known as a “problem” in art history: how do we make sense of these paintings, apparently in a Christian style and bearing Christian iconography, in an Islamic palace?2

The denotation of the problem as “Christian” imagery in an “Islamic” palace is of course an oversimplification, driven by contemporary disciplinary divisions. Medieval viewers, especially those accustomed to the hybrid cultures of the Iberian peninsula, would not necessarily have understood the paintings in these terms. It remains, however, to determine what medieval viewers would have understood from all three of the Alhambra’s ceiling bays.

Many attempts have been made to tie specific episodes from the Alhambra’s famous secular figural ceiling paintings to specific literary narratives. Despite the Alhambra’s Nasrid patronage, both the visual and literary connections raised are generally from Christian sources, suggesting the cultural hybridity of the fourteenth-century Iberian peninsula. I suggest that attempting to pin particular motifs to particular narratives is not only – in at least some cases – futile, but also, more importantly, misses the point of the paintings. The aim of these sophisticated paintings was to connect fiction to reality, and reality to fiction: in particular, to illustrate the chivalry of historical members of the Order of the Banda or Scarf by portraying them in the visual forms of widely-recognized protagonists of romance. While the romance paintings suggest secular narratives, in fact they select and display visual motifs for a non-narrative purpose.

The arms of the Order of the Banda are explicitly painted in all three bays, a fact which has been recognized by numerous scholars. However, no one has yet suggested that this chivalric order has a prominent or structuring role within these paintings. Using attention to iconography, color, and composition, I argue that the painted actions, heraldic colors, and repeated inclusion of the coat of arms of the Banda within the paintings are all intended to reference this chivalric order (Figures 2, 3, 4). I maintain that not only can each of the activities included in the side bays (hunts, lovers’ meetings, combats) be read in relation to the written requirements of the Order, but the major colors in the costumes of almost all of the so-called narrative figures are substantially red with gold, the heraldic colors shown here in the arms of the Banda and those used in the Order of the Banda in the later fourteenth century.3 The women in the castle, the man who falls from horseback, the couple at the fountain, the men who beat the bush for game, the knight who spears a boar, the couple playing chess – indeed, nearly every single one of the dozens of figures included in the side bays – are each dressed in colors which are substantially red and gold. One should not discount the fact that red and gold stand out well against the dark foliage; still, orange, turquoise, pink and pale blue would have done so as well. The castles display red roofs, turrets, and shutters, frequently with gold trim; coats of arms showing the Banda are not placed randomly on the castle walls but instead are carefully placed to mark the castle entrances, suggesting their inhabitants’ allegiance to the Banda. Yet today’s scholars, seduced by the challenge of identifying “the narrative,” have repeatedly passed over these and other suggestive visual cues.

The Order of the Banda or Scarf was a chivalric order founded in Christian Castile in 1330.4 It was bestowed both upon Castilians and individuals from various nations whom the Castilian king wished to honor. The emphasis on loyalty within the statutes of the Banda took on a particular historical inflection during the reign of the Castilian king Pedro, who reigned 1350 – 1366 and then again 1367 – 1369. Pedro’s rule was interrupted when his half-brother seized the throne in 1366. Pedro was also known “the Cruel” or “the Just” (depending on your perspective on his serial killings of those who contested his claim for the Castilian throne). The device of the Banda was used during this period as a device signaling that the bearer was a recipient of the favor of the Castilian king.5 Muhammad V was among those who fought to restore the Castilian throne to Pedro. Muhammad V’s loyalty in 1366-37 to Pedro was understandable, as just a few years previously, in 1362, Pedro had invited the usurper of Muhammad V’s throne to Castile and there butchered him, restoring Muhammad V’s rule in Granada.

I suggest that the Alhambra’s figural ceiling paintings depict an intentional collage of scenes drawn from romance, but these paintings were not intended to represent any particular romance. These compositions were assembled instead with another purpose in mind: to refer to a chivalric order, its coat-of-arms, heraldic colors, and prescribed courtly activities. The visual structure of the ceilings, their composition, and color, are powerful reminders that other kinds of content can be just as important as narrative.

Bibliography

Boulton, D. Arcy Jonathan Dacre. The Knights of the Crown: The Monarchical Orders of Knighthood in Later Medieval Europe 1325-1520. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press, 1987.

Dickie, James. “The Palaces of the Alhambra.” In Al-Andalus, the Art of Islamic Spain, edited by Jerrilynn Dodds. 135-51. New York: the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992.

Dodds, Jerrilynn Denise. “The Paintings in the Sala De Justicia of the Alhambra: Iconography and Iconology.” Art Bulletin 61, no. 2 (1979): 186-97.

Robinson, Cynthia, and Simone Pinet, eds. Courting the Alhambra: Cross-Disciplinary Approaches to the Hall of Justice Ceilings. Vol. 14.2-3, Medieval Encounters (Special Issue), 2008.

Notes

1 The precise date of the completion of the ceiling paintings is unknown. James Dickie and others agree that the completion of the Palace of the Lions in the Alhambra took place during the second reign of Muhammad V; that is, 1362-91. James Dickie, “The Palaces of the Alhambra,” in Al-Andalus, the Art of Islamic Spain, ed. Jerrilynn Dodds (New York: the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992), 145.

2 Jerrilynn Denise Dodds, “The Paintings in the Sala de Justicia of the Alhambra: Iconography and Iconology,” Art Bulletin 61, no. 2 (1979): 186-97; Cynthia Robinson and Simone Pinet, eds., Courting the Alhambra: Cross-Disciplinary Approaches to the Hall of Justice Ceilings, vol. 14.2-3, Medieval Encounters (special issue) (2008).

3 D. Arcy Jonathan Dacre Boulton, The Knights of the Crown: the Monarchical Orders of Knighthood in Later Medieval Europe 1325-1520 (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press, 1987), 86-89.

4 Ibid., 52.

5 Ibid., 60.