PDF

Download

Citations

Click and drag then release to select a passage to cite.

Annotations

How to submit annotations to Mizan Journal articles:

your work is published.

Search within

The Islamic State as an Empire of Nostalgia

Image

Audio

Video

Chart or Graph

The Islamic State as an Empire of Nostalgia

Introduction

So rush O Muslims and gather around your khalīfahArabic for 'caliph.', so that you may return as you once were for ages, kings of the earth and knights of war. Come so that you may be honored and esteemed, living as masters with dignity. Know that we fight over a religion that Allah promised to support. We fight for an ummahArabic for 'community,' typically signifying the worldwide community of Muslims. to which Allah has given honor, esteem, and leadership, promising it with empowerment and strength on the earth. Come O Muslims to your honor, to your victory. By Allah, if you disbelieve in democracy, secularism, nationalism, as well as all the other garbage and ideas from the west, and rush to your religion and creed, then by Allah, you will own the earth, and the east and west will submit to you. This is the promise of Allah to you. This is the promise of Allah to you.1

The declaration of a caliphate by the Islamic State in June 2014 revived debates on the nature of the caliphate itself, which had formerly seemed to be a topic of interest only to Muslim theologians and historians of the Islamic world. One key question was how a movement that emerged in a civil war environment in Syria (where factions among the Sunni majority sought the ouster of the minority Alawite dictatorship of Bashar al-Assad) and Iraq (where a Sunni minority was alienated from Shi’ite majority national government) could attract so many foreign Muslims to fight for it under the Islamic State banner. After all, civil wars sparked by fierce political grievances are common worldwide, but rarely attract enthusiastic foreign volunteers willing to die for them. But as Alexis de Tocqueville noted in regard to the French Revolution, movements claiming to be based on universal ideas transcend such boundaries and have a different dynamic:

By seeming to tend rather to the regeneration of the human race than to the reform of France alone, it roused passions such as the most violent political revolutions had been incapable of awakening. It inspired proselytism, and gave birth to propagandism; and hence assumed that quasi religious character which so terrified those who saw it, or, rather, became a sort of new religion, imperfect, it is true, without God, worship, or future life, but still able, like Islamism, to cover the earth with its soldiers, its apostles, and its martyrs.2

As Tocqueville’s reference to the rise of Islam indicates, before the late eighteenth century movements that inspired such widespread trans-national mobilization had always been religious in nature, the most recent example being the rise of Protestantism in sixteenth century Western Europe and the political upheavals it produced. While succeeding movements of this type in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (democratic, nationalist, or socialist) were all secular in origin, they did share something in common with similar earlier religious movements. Like their predecessors, they were future-oriented, proclaiming the promise of a new and better world once the corrupt old one was swept away. Whether religious or secular, all promised their followers an idealized future in which sacrifice today would be redeemed in a better tomorrow.

By contrast, the Islamic State is backward-looking. Instead of calling for sacrifice to create a new future utopia, it seeks to revive a structure long dead—the Islamic caliphate—interpreting it as the lost Muslim ideal that can be restored only by using past Islamic precedents as a strict template. No policy, law, or political strategy can be deemed legitimate unless it is grounded in the institutions and examples provided by the early Muslim state and its divinely guided leaders. In this process the Islamic State rejects the structure of the modern nation state system and seeks to replace it with a universal empire of religion, announcing that all existing state structures lose their legitimacy upon the arrival of the caliphate: “The legality of all emirates, groups, states, and organizations, becomes null by the expansion of the khilāfah’s authority and arrival of its troops to their areas.”3 Like similar religious movements in the past, it promises its followers either ultimate victory or the consolation of bringing the world itself to an end in a fiery apocalypse.

While literature on the caliphate is enormous, not enough attention has been paid to its recent re-creation as a variety of secondary imperial state formation in which the trappings and ideologies of long lost empires are used as a political tool to build a new one. Such “empires of nostalgia” draw on a strong cultural tradition of a perceived golden age that can be reclaimed now or in the near future. Only one of many types of secondary empire, empires of nostalgia have a distinct form that is rooted in very deep and specific cultural traditions whose appeal is usually a mystery to those who do not share it. Further, in the twenty-first century the Islamic State is not alone in appealing to nostalgia for vanished empires. In the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse, Vladimir Putin now portrays Russia as the beleaguered defender of an Eastern Orthodox religious legacy inherited from the Byzantines, appealing to a peculiarly Russian cultural ethos that undergirds it. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has taken to reviving an appeal to the memory of the Ottoman Empire that the founders of Turkish Republic abolished and buried. The Communist Party heirs to Mao’s radical assaults on traditional Chinese culture now have a string of worldwide Confucius Institutes to market these formerly attacked values worldwide. Both empires and nostalgia are thus worth a closer look.

A world of empires: primary and secondary

Until the end of the First World War, empires were the most complex and dominant form of political organization in Eurasia, and had been so for more than two millennia. They had two distinctive forms that had different origins: large primary empires that that were self-generating and self-supporting, and smaller (in territory or population) secondary empires that emerged in response to them. In some cases, overly successful secondary empires transformed themselves by evolving into primary ones, usually through campaigns of conquest and incorporation into a larger hybrid system.

Primary empires were states established by conquest that had sovereignty over continental- or subcontinental-sized territories that incorporated millions or tens of millions of people into a unified and centralized administrative system.4 They financed themselves largely from internal resources through systems of direct taxation or tribute payments derived from their component parts. They maintained large and permanent military forces to protect marked frontiers and preserve internal order. Historically, primary empires were one or two orders of magnitude larger in territory and population than rival polities that (if they avoided incorporation) lived on their margins: regional kingdoms, city-states, or tribal confederations. Classic examples from Eurasia included the many empires that united China (Qin, Han, Tang, Ming, and Qing dynasties) over the course of two millennia,5 the Roman and Byzantine Empires that long dominated the Mediterranean basin,6 and the many iterations of the Persian Empire and its successor states on the Iranian Plateau and Central Asia.7

After the rise of Islam, the caliphate became a huge primary empire that ran from Spain and North Africa through the Arab Middle East and beyond into the Iranian Plateau and Central Asia.8 Upon its breakup, successor primary empires eventually appeared in what had become the Islamic world. The largest and most long-lasting was the Ottoman Empire that first emerged in the thirteenth century and by the eighteenth ruled from the Balkans to the borders of Iran, from the Caucasus to the Arabian Peninsula, Egypt, and parts of North Africa. But other significant and long-lasting empires in the Muslim world that emerged around the same time period were established by the Timurids in Central Asia, the Safavids in Iran, and the Mughals in India.9

Such primary empires may have begun with the hegemony of a single region or ethnic group, but they all became more cosmopolitan over time with the incorporation of new territories and people very different from themselves. Indeed, the main characteristic of a successful primary empire was its ability to thrive on diversity and make it a strength. An important aspect of its political structure, one that gave it great stability, was that the empire’s founding ruling elite could be replaced without bringing about the collapse of the state structure. Polities whose founding elites defined the state by their exclusive dominance of it lacked this capacity—they either had to limit the size of the state to one they could manage unaided, or risk its collapse at the hands of disaffected peoples whose own elites became permanent enemies of the state. The leaders of the early Islamic conquests experienced this tension firsthand when they broke away from a narrow conception of participation (Islam as a religion exclusive to the Arabs) to a strikingly diverse one (Islam as a world religion) in which all believers could potentially be part of a single political system in which there was an opportunity for a wide range of people to participate.

Empires were aided in this process by various types of long-term imperial projects designed to imprint particular aspects of their own cultural system on all peoples under their rule. It was not an attempt by the elite to create clones of themselves, but rather to foster a common core of values that would add to existing ones. It was a project that moved in stages from coercion and cooptation to cooperation and identification. It produced a vision of unity that extended well beyond force and created what we often identify as a civilization that long outlasted the political system that first produced it.

Examples include the use of Chinese ideographs and Confucian models of morality and governance in East Asia, or the survival of the use of Latin and Roman law and administration in the West. Religion could also prove a strong foundation for an imperial project in some parts of the world, as when the Romans and Byzantines began to see themselves as protectors and then missionaries for Christianity. Of course, the common use of the term “Islamic world” even today is a legacy of the founders of the caliphate whose project of making Muslim identity paramount over all others long survived that institution’s political collapse.

If classic primary empires were the product of internal development and sustained themselves through the exploitation of their own resources, there were also a large number of imperial polities that were the products of secondary empire formation. That is, they came into existence as a response to primary imperial state formation elsewhere. Although they often had tremendous power and influence, and mimicked primary empires in their actions and policies, they lacked most of their essential attributes. Most notably, they often exerted direct rule over relatively few people, even when their geographical scope was huge. But the common element that really set all of them apart from primary empires was the absence of an internal domestic resource base sufficient to support the polity, and a dependence on external resources to make up that deficiency. Secondary empires acquired these resources in various ways, but always from people and states they did not attempt to rule directly. They were thus “shadows” that took on the form and power of primary empires without all of their substance.

There were four different types of shadow empires:

Mirror empires that rose and fell in tandem with their rivals because they were responses to challenges presented by a neighbor’s imperial centralization. The best examples are the series of nomadic empires in Mongolia that emerged when China was unified under native Chinese dynasties.10 The danger China presented gave incentive for the nomads to unite, but these polities preserved themselves only by extracting resources from China, not by taxing their own people. Classic dyads included the Han/Xiongnu from 200 BCE to 200 CE and the Tang/Turks from 600–900 CE. When native Chinese dynasties collapsed, so did their nomadic counterparts that had become parasitically dependent on them.

Maritime trade empires that held the minimum amounts of territory needed to extract economic benefits from other polities that organized the production of the goods they traded. By focusing their investments on ports and strong navies, they attempted to control the means of exchange rather than the means of production. Examples include imperial Athens, Carthage, and Venice. In early modern times the Portuguese, Dutch, and British penetration of Asia took this form.11 They were vulnerable to rival naval powers but tended to be shattered only when existing land-based powers were strong enough to either destroy their trade networks or target their centers for elimination, as when Rome destroyed Carthage or the Spartans defeated the Athenians in the Peloponnesian War.

Vulture empires that were created by leaders of frontier provinces or client states who turned the tables on their erstwhile imperial masters in times of political and economic distress by seizing control of parts of the old empires. They characteristically sought to adopt the cultural values and administrative structures of the primary empires they occupied rather than impose new ones. Although their systems of governance were less sophisticated than the imperial systems they replaced, the ability to preserve order in the midst of anarchy gave them a competitive advantage. Ironically, the more successful they proved to be at restoring order, the more they undermined the rationale for their rule. They historically lost power when the structure of the old regime and its indigenous elites recovered enough to exclude the interlopers. Examples of such vulture empires include most of the many foreign dynasties that ruled north China,12 or the Nubians who briefly ruled ancient Egypt.13 In other cases, vulture empires emerged as masters of weak secondary imperial polities that lay beyond the reach of bigger primary empires. These shadow empires, such as the Hapsburg dynasty in Central Europe or the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in Eastern Europe, incorporated neighboring marginal territories but never produced an overwhelmingly strong center to unify them.14

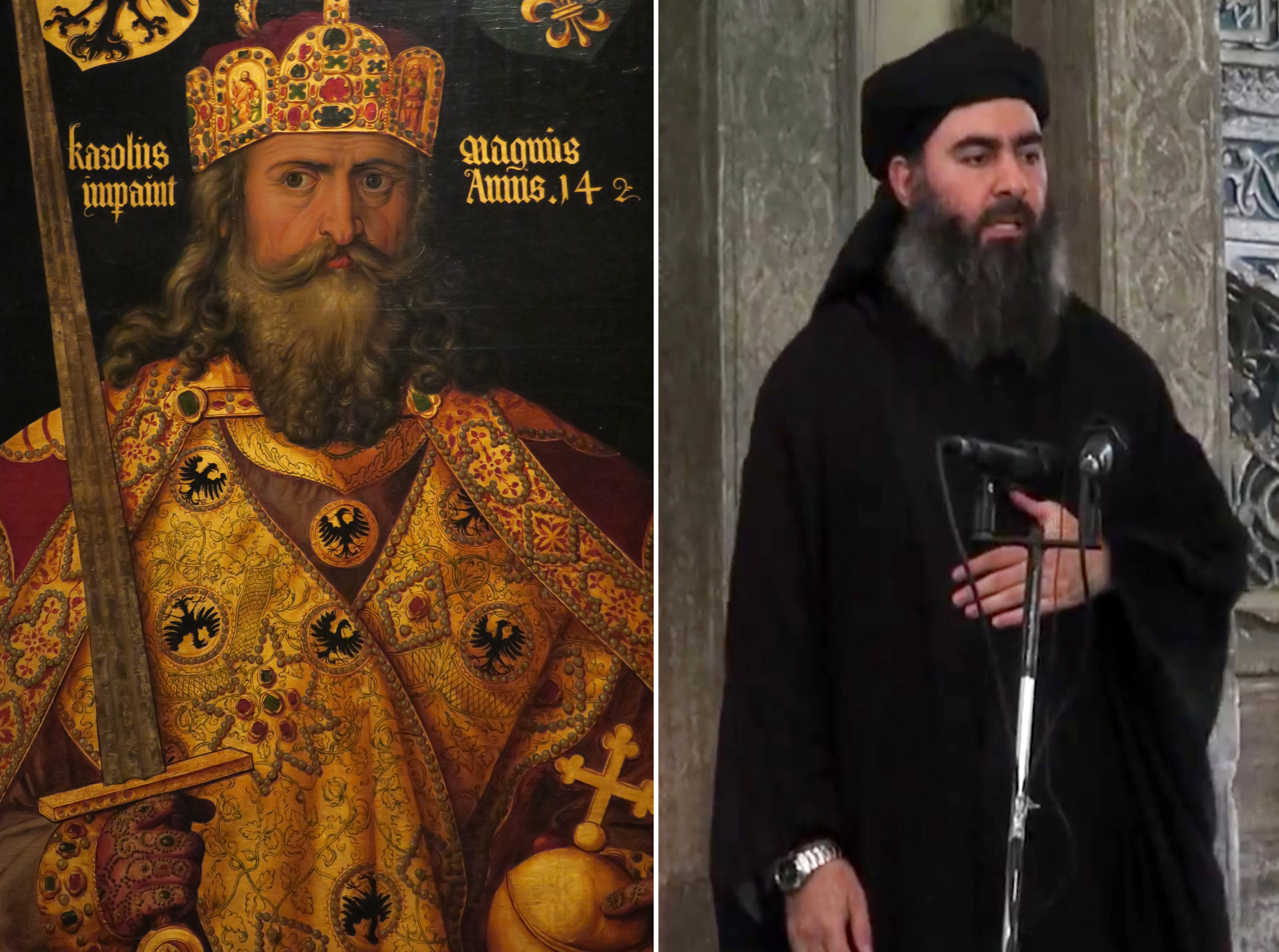

Empires of nostalgia were based on the remembrance of organizations past. They claimed an imperial tradition and the outward trappings of an extinct empire, but could not themselves meet the basic requirements of an imperial state such as direct control of territory, true centralized rule, or significant urban centers. Indeed, they often lacked the territorial size or population to justify their pretensions—as when rulers of former provinces of an old empire promoted themselves to imperial rank. Examples include the medieval Carolingian Empire established by Charlemagne and its long-lived successor, the Holy Roman Empire. 15 As Voltaire acerbically complained, the “agglomeration that was called and which still calls itself the Holy Roman Empire is neither Holy, nor Roman, nor an Empire,”16 yet it survived as an institution for one thousand years.17 No better definition of a shadow empire of nostalgia could be had. As we will see, the caliphate has had a similar hold on the Islamic imagination.

Shadow empires in each of these categories could on some occasions evolve into true primary empires. The Mongol Empire founded by Genghis Khan in 1206 began like other mirror nomadic empires seeking only to extort northern China but ended up conquering it, and most of Eurasia as well, to become the largest land empire in history under his successors.18 Few maritime empires successfully moved to directly rule the lands they exploited economically, but the expansion of the British in India from a group of private armed traders in the seventeenth century to rulers of the whole subcontinent in the mid-nineteenth is an example of how it could be done.19 And while most vulture dynasties that ruled north China were never able to expand very far south, in 1644 the Manchu Qing dynasty did—quickly moving from vultures to become primary imperial rulers of all China for the next two-and-a-half centuries.20 When secondary empires did transform themselves into primary ones, however, the legacy of their earlier experiences as outsiders often profoundly affected how they saw the world. Unlike native Chinese rulers like the Ming dynasty it succeeded, for example, the Qing treated non-Han peoples as potential partners to be co-opted rather than inveterate enemies to be walled off.21 In South Asia, even after their de facto displacement of the Mughals and other powerful Indian states, the British were loath to take on the formal responsibilities of governance, and never lost their mercantile preoccupations that put profit first. Only after various forms of indirect rule failed and put their position in India at risk during the so-called Sepoy Rebellion of 1857 did the British government in London finally end the East India Company’s responsibility for administration there.22

Empires of nostalgia and cultural memory

Of all the shadow empires, those based on nostalgia are perhaps the most unusual and the most shadowy. They exist only in the minds of those who perceive them and are rooted in conceptions of empires past that never truly existed in the ideal forms that were attributed to them. Their origins were firmly rooted in the lasting cultural memory left by powerful empires on the regions and peoples they ruled or bordered. When these empires collapsed (particularly if that collapse resulted in many generations of political anarchy, population decline, and economic decay), the extinct imperial structure was often imbued with the aura of a former “golden age” now lost.

The memory of this empire and its trappings retained such an ideological hold over future generations that it could be used as a powerful tool in later times when new rulers sought to build states or empires of their own. It also provided many of them with templates for building a large-scale administration where these had disappeared. This tendency was strongest in China where the cosmological myth of a necessary emperor ruling “All under Heaven” emerged even before it was fully united, and later provided the impetus to recreate a united empire after it was lost.23 Any conquerors who could reunite China after a period of disunion—even “barbarians” like the Mongols and Manchus—were deemed legitimate if they succeeded.24 The founding myth of unity that came into being with the first Qin emperor in the third century BCE was so strong that (unlike in the West) primary empires succeeded in reuniting China after each period of state collapse. (Some today would see the People’s Republic of China as the latest in this series of unified Chinese states attempting to restore its former status as the dominant power in East Asia.)

China’s success in recreating imperial unity after collapse (periods that often spanned many centuries) was the exception rather than the rule, however. In most places the dream of reestablishing a primary empire in its past form always remained a distant hope rather than an achievable reality. Still, the very idea of the old empire provided an ideological basis for those leaders seeking to centralize power against the opposition of powerful local elites. Charlemagne’s Carolingian Empire fell squarely into this category because it lacked most of the basic necessities of state formation, let alone empire formation. Early medieval Europe lacked big urban centers and an integrated economy. Its rulers could raise only rudimentary taxes and relied on feudal troop levies rather than standing armies. Indeed, the entire feudal system of land grants run by autonomous local notables was antithetical to Roman principles of imperial rule. These continued only in the Roman Catholic Church, whose hierarchical clergy and institutional ownership of land far better reflected a Roman imperial template.25

Still, it was recognized as an empire at the time, and continues to hold an outsized place in medieval European history. Why? Because it was the first widely accepted attempt to bring back the political model of Rome to the Catholic Christian West, and it struck a powerful cultural chord in regions that saw themselves as falling far below the level of civilization that had once existed. It would serve as a potent ideological weapon in the (ultimately unsuccessful) drive to centralize the petty states of feudal Europe into a single imperial polity, as well as later giving Western Europe an imperial vision of itself in dealing with the Islamic world during the Crusades.26 It had far less of an impact in the territories of the Eastern Roman Empire where the Byzantines (allied with the Eastern Orthodox Christian Church) successfully maintained a unified imperial structure and centralized military for a millennium after its collapse in the West.27

In empires of nostalgia, rulers tied their own legitimacy to something that no longer existed but still attracted willing participation: the desire to be part of a political project that inspired hope of better things to come by appealing to past glory. Petty struggles for power and supremacy could be dressed in more attractive clothing and tied to loftier goals that had strong cultural appeal. Cooperation was thus easier to achieve, and recognition of the new ruler and his state as more legitimate, if it could be linked to an admired (if long gone) empire rather than being viewed as an unwelcome innovation imposed by a usurping power-hungry clique.

Because empires of nostalgia draw their power from the realm of cultural memory, they do not travel well. The West’s infatuation with ancient Rome has little resonance in China, nor does the epic rise and fall of Chinese dynasties stir any emotion in the West. Yet in their own realms, such remembrances of empires past can be tenacious. Indeed, it appears the only way to kill the nostalgia for one is to inculcate a new cultural order. While the model of Rome remained strong in the West, it was lost to Roman North Africa after the Islamic conquest. From that point on, people there were invested in empires of nostalgia drawn from the Islamic tradition. Few were more potent than the idea of the caliphate.

The caliphate and its new incarnations

The most powerful empire of nostalgia in the Islamic world has always been the caliphate. Seen as a framework for governance sanctified by the Prophet and his immediate successors that began in the mid-seventh century CE, its early conquests were spectacularly successful. They laid the groundwork not only for a new imperial structure but one uniquely combining the Muslim religion and the state. Like most empires, its internal politics were fractious and not very edifying for either those who fell victim to them or later historians. Even as the empire expanded externally, it was divided by civil wars over who should rule the caliphate. The Umayyad Caliphate displaced those who were supporters of the heirs of the Prophet’s son-in-law ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib (who maintained a distinct identity as Shi’ites). The Umayyads ruled the caliphate until 750 when they were displaced by the Abbasids. The Abbasids consolidated their power in part by murdering all the Umayyad pretenders they could find. Despite its bloody beginnings, the Abbasid dynasty marked the highpoint of caliphal power and has long been viewed as the period of Islam’s greatest influence culturally and politically. Its power declined in the mid-ninth century when it lost control of outlying territories and was challenged by many rebellions. The dynasty lost secular authority when conquered by new regional dynasties, beginning with the Buyids from Iran in 945. However, the prestige of the caliphate was so high that all succeeding Muslim dynasties acknowledged the caliph’s spiritual authority. The caliphate ended when the Mongols sacked Baghdad in 1258 and murdered the last caliph, abolishing the institution. Coming from a different cultural tradition, they had no particular respect or sympathy for Islamic institutions (although their descendants who stayed would eventually adopt the religion).28 The Ottoman sultans, who first took up the title for themselves in the fourteenth century, began to stress the importance of the institution for their own legitimacy beginning in the eighteenth century, in a fairly successful bid to portray themselves as defenders of Islam against the growing power of Christian Europe.

While appeals to an idealized Islamic past had a long history, particularly in the battle to throw off European colonial domination in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Islam as a framework for statebuilding had seemingly lost the battle of ideas to Western democratic, nationalist, or socialist movements that either rejected religion outright or reduced its writ to the private sphere. Such secular movements all sought to build ideal human societies of some sort and saw religion (of whatever type) as an obstacle to achieving their goals. Beginning first with the American and French revolutions in the late eighteenth century, religious institutions in the West were stripped of any privileged political role even in countries like Britain that still recognized a state religion. During the twentieth century, socialist states like the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China attacked religious belief and religious institutions directly, proclaiming atheism as national policy. Following the end of World War I, most leaders of newly independent states in Muslim majority countries (or those seeking independence) similarly grounded their political legitimacy in a variety of secular rather than religious guises: nationalism, kingship, democracy, or radical socialism.

This can be seen most strongly among the secular nationalists who established all the regimes of the Arab world following the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire (save Saudi Arabia). They viewed religion more as a source of the region’s weakness rather than strength, and believed it needed to be cast aside to build state power. Non-Arab Muslim polities adopted similar policies of state secularism in pursuit of national development. In the 1920s, it was the core ideology of Turkey’s Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who abolished the caliphate in 1924 during his successful drive to create a secular republic. Reza Shah Pahlavi attempted to modernize his country by stressing Iran’s pre-Islamic greatness under the Persian Empire. Even in distant Afghanistan, King Amanullah Khan spent the 1920s attempting to replace a legal system based on Islamic law with secular courts employing a secular law code. A British Indian political agent at the time went so far as to conclude that the rise of secular modernist reformers was “an illustration of the broad fact already noticed that the impulse behind recent movements in the East is nationalist rather than religious in character, and that when the two forces come into conflict the advantage lies with the nationalist.”29

Almost a century later, this conclusion appears to have been premature. Beginning with the Iranian revolution in 1979, the Islamic world has been swept by a revival of religious political movements in which the secular nationalists have been at a clear disadvantage. But the form such Islamic movements has taken has varied significantly. Some Sunni Muslim Brotherhood followers saw their movement as able to work within the structures of existing secular states, with the expectation of moving them toward such religious goals as the implementation of shari’ah law. Others sought to implement purely Islamic governments with no inclination to share power. In Shi’ite Iran, clerics set the rules of the Islamic Republic and oversaw its management. In the Sunni world, Mullah Omar, the Taliban leader of Afghanistan, proclaimed the country an independent Islamic emirate and gave himself the title of amīr al-muʾminīn (Commander of the Faithful) in 1996. Notably, however, he did not proclaim himself caliph, or suggest that the Afghan emirate marked the beginning of a new caliphate. In this he appears to have been following Al-Qa’idah opinion that a caliphate could only come into existence after the lands of the original caliphate (including places no longer Muslim, like Spain) had come under its control. Significantly, Mullah Omar was neither an Arab nor from the Prophet’s tribe, qualifications historically deemed necessary for becoming a caliph (although these criteria had not applied during the many centuries when the Ottoman Turkish sultans claimed the title).30

The shift of the concept of the caliphate from some future culminating endpoint that would emerge only after Islam’s final victory over its rivals to a contemporary institution designed to bring that victory became manifest in June 2014. At that time, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) endorsed Abū Bakr al-Baghdādī’s declaration of himself as caliph in the territories ISIS occupied. In sharp contrast to Mullah Omar, Baghdādī is both an Arab and a descendant of the Prophet’s tribe of Quraysh. The large number of Muslim supporters, including thousands of foreign fighters and even women, who have flocked to join in the fight for this new caliphate has surprised many observers. Their enthusiasm for participating in a fight that is not their own is best explained by viewing the Islamic State and its declared caliphate as an “empire of nostalgia” that attracts precisely because it is an attempt to recreate a lost empire of glory when Muslims were politically and culturally dominant.

The original caliphate was a transnational empire, so those attempting to revive it now see themselves as legitimate in reaching out to the entire Muslim ummah for support. Like other purveyors of empires of nostalgia, however, its culturally resonant project is based on illusions designed to soften a harsher reality. The war the Islamic State portrays as a noble and attractive struggle pitting believers against unbelievers to create an ideal Islamic state is in reality a vicious civil war conflict within the Muslim community. Only by declaring its equally Muslim opponents (albeit of different sects or political factions) kuffār or infidels, apostates worthy of death (that is, takfīrThe act of one Muslim asserting that another Muslim, on the basis of beliefs or actions, is actually not a Muslim but rather an infidel (kāfir).), can the new caliphate justify its brutal tactics that bring mass slaughter and oppression to the heartland of the old caliphate.

In this, ISIS lays the foundation for its demise: successful empires succeed by tempering their violence through the accommodation of diversity. Power may be won by the sword, but it is maintained by softer means. As conquerors of large non-Muslim communities, rulers of the early caliphate needed to accommodate indigenous groups and accepted them as long as they accepted the caliphate’s rule and paid taxes. By contrast, the current Islamic State works in an environment in which Muslim communities constitute the vast majority. Ironically, some Christian communities have received better protection that their Muslim neighbors because the original caliphate granted them specific protections not shared by other religions (such as the Yazidis) or those fellow Muslims they have deemed heretical.31 By defining its caliphate so narrowly, they risk the fate of similar radical Islamic movements such as the seventh-century Kharijites, who also viewed most other Muslims as enemy apostates. They were marginalized and destroyed by unified opposition to them in both the Sunni and Shi’ah communities.

Of all the varieties of shadow empires, an empire of nostalgia is least likely to make the transition into a primary empire. Even in China where new dynasties grounded themselves in older imperial traditions, that transition was only the finishing touch that transformed conquering rebels and foreign invaders into legitimate rulers. In this they resemble what anthropologists call revitalization movements whose charismatic leaders seek to bring about a social transformation of the world that would empower their followers.32 To attempt the recreation of an old imperial structure on the ground, however, invites attack by rivals of all sorts that few such movements could withstand. Empires of nostalgia thus do best in a world where there are no powerful state rivals, in times when long periods of political turmoil produce a desire for order even where it cannot be delivered. Where strong states do exist, such movements are almost always destroyed as autonomous political entities, a prospect that often leads to the belief that divine intervention will save the day, as the ISIS Caliphate’s English-language media mouthpiece asserts. Called Dabiq, it is named for the site in northern Syria where some believe the Muslim version of Armageddon will occur.

About the author

Thomas Barfield is an anthropologist who received his Ph.D. from Harvard University. He conducted ethnographic fieldwork with nomads in northern Afghanistan in the mid-1970s and is author of The Central Asian Arabs of Afghanistan (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1981); The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China (Oxford: Blackwell, 1989); and co-author (with Albert Szabo) of Afghanistan: An Atlas of Indigenous Domestic Architecture (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1991). Professor of Anthropology at Boston University, Barfield is also President of the American Institute for Afghanistan Studies. In 2007 Barfield received a Guggenheim Fellowship that supported the research for his most recent book, Afghanistan: A Cultural and Political History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010).

Notes

All digital content cited in this article was accessed on or before September 21, 2016.

[1] The Islamic State’s official declaration of its establishment of a caliphate was published in a number of languages as “This is the Promise of Allah,” Al Hayat Media Center, June 29, 2014 (https://ia902505.us.archive.org/28/items/poa_25984/EN.pdf), 6.

[2] Alexis de Tocqueville, The Old Regime and the Revolution, trans. John Bonner (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1856), 27.

[3] “This is the Promise of Allah,” 5.

[4] This and subsequent sections pf this article are taken directly from Thomas J. Barfield, “The Shadow Empires: Imperial State Formation along the Chinese-Nomad Frontier,” in Susan E. Alcock, Terence N. D’Altroy, Kathleen D. Morrison, and Carla M. Sinopoli (eds.), Empires: Perspectives from Archeology and History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 21–41.

[5] See Part 1 of John King Fairbank and Merle Goldman, China: A New History (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2006).

[6] Edward Gibbon, History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (3 vols., New York: Modern Library, 1984).

[7] Touraj Daryaee (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

[8] Marshall G. S. Hodgson, The Venture of Islam: Conscience and History in a World Civilization, Vol. 1: The Classical Age of Islam (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974).

[9] Stephen Dale, The Muslim Empires of the Ottomans, Safavids, and Mughals (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

[10] Thomas Barfield, “The Hsiung-nu Imperial Confederacy: Organization and Foreign Policy,” Journal of Asian Studies 41(1981): 45–61.

[11] Sanjay Subrahmanyam, “Written on Water: Designs and Dynamics in the Portuguese Estado da Índia,” in Alcock et al. (eds.), Empires, 42–69.

[12] Thomas Barfield, The Perilous Frontier (Oxford: Blackwell, 1989), Chapters 3, 5, and 7.

[13] Robert Morkot, “Egypt and Nubia,” in Alcock et al. (eds.), Empires, 227–251.

[14] Zenonas Norkus, “The Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the Retrospective of Comparative Historical Sociology of Empires,” World Political Science Review 3 (2007), 1–41 (http://www.fsf.vu.lt/users/zennor/pub/NorkusWorldPoliticalScienceReview.pdf), 4.

[15] John Moreland, “The Carolingian Empire: Rome Reborn?,” in Alcock et al., Empires, 392–418.

[16] Voltaire, Essai sur les mœurs et l’esprit des nations et sur les principaux faits de l’histoire depuis Charlemagne jusqu’à Louis XIII (2 vols.; Paris: Garnier frères, 1963), 1.683.

[17] Peter H. Wilson, Heart of Europe: A History of the Holy Roman Empire (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press, 2016).

[18] David Morgan, The Mongols (Oxford: Blackwell, 1990).

[19] Jeremy Black, The British Seaborne Empire (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004).

[20] Jonathan D. Spence and John E. Wills (eds.), From Ming to Ch’ing: Conquest, Region, and Continuity in Seventeenth-Century China (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979).

[21] William T. Rowe, China’s Last Empire: The Great Qing (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009).

[22] Philip Lawson, The East India Company: A History (London: Longman, 1993).

[23] Robin Yates, “Cosmos, Central Authority, and Communities in the Early Chinese Empire,” in Alcock et al., Empires, 351–368.

[24] Hok-Lam Chan, Legitimation in Imperial China: Discussions Under the Jurchen-Chin Dynasty (1115–1234) (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1984).

[25] Moreland, “The Carolingian Empire: Rome Reborn?”

[26] Anne A. Latowsky, Emperor of the World: Charlemagne and the Construction of Imperial Authority, 800–1229 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013).

[27] Edward Luttwak, The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009).

[28] Or for any other religious institutions that stood in the way of conquest. A generation earlier, the Mongols had threatened the Pope in Rome in the same manner as they did the caliph, but he was spared by a fortuitous withdrawal of their army to Mongolia before they could carry out his destruction. In the Near East, they fought a war of extermination against the so-called Assassins, an Islamic sect whose descendants became the Isma’ili followers of the Aga Khan.

[29] Senzil K. Nawid, Religious Response to Social Change in Afghanistan, 1919–29: King Aman-Allah and the Afghan Ulama (Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 1999), 52.

[30] Reza Pankhurst, The Inevitable Caliphate?: A History of the Struggle for Global Islamic Union, 1924 to the Present (London: Hurst, 2013).

[31] Jacob Marcus, The Jew in the Medieval World: A Sourcebook, 315–1791 (New York: Jewish Publication Society, 1938), 13–15; Adam Hoffman and Rachel Hoffman, “ISIS and the Implementation of Islamic Rule,” TonyBlairFaithFoundation, August 27, 2014.

[32] Anthony F. C. Wallace, “Revitalization Movements,” American Anthropologist 58 (1956): 264–281.

The Islamic State as an Empire of Nostalgia

Introduction

So rush O Muslims and gather around your khalīfahArabic for 'caliph.', so that you may return as you once were for ages, kings of the earth and knights of war. Come so that you may be honored and esteemed, living as masters with dignity. Know that we fight over a religion that Allah promised to support. We fight for an ummahArabic for 'community,' typically signifying the worldwide community of Muslims. to which Allah has given honor, esteem, and leadership, promising it with empowerment and strength on the earth. Come O Muslims to your honor, to your victory. By Allah, if you disbelieve in democracy, secularism, nationalism, as well as all the other garbage and ideas from the west, and rush to your religion and creed, then by Allah, you will own the earth, and the east and west will submit to you. This is the promise of Allah to you. This is the promise of Allah to you.1

The declaration of a caliphate by the Islamic State in June 2014 revived debates on the nature of the caliphate itself, which had formerly seemed to be a topic of interest only to Muslim theologians and historians of the Islamic world. One key question was how a movement that emerged in a civil war environment in Syria (where factions among the Sunni majority sought the ouster of the minority Alawite dictatorship of Bashar al-Assad) and Iraq (where a Sunni minority was alienated from Shi’ite majority national government) could attract so many foreign Muslims to fight for it under the Islamic State banner. After all, civil wars sparked by fierce political grievances are common worldwide, but rarely attract enthusiastic foreign volunteers willing to die for them. But as Alexis de Tocqueville noted in regard to the French Revolution, movements claiming to be based on universal ideas transcend such boundaries and have a different dynamic:

By seeming to tend rather to the regeneration of the human race than to the reform of France alone, it roused passions such as the most violent political revolutions had been incapable of awakening. It inspired proselytism, and gave birth to propagandism; and hence assumed that quasi religious character which so terrified those who saw it, or, rather, became a sort of new religion, imperfect, it is true, without God, worship, or future life, but still able, like Islamism, to cover the earth with its soldiers, its apostles, and its martyrs.2

As Tocqueville’s reference to the rise of Islam indicates, before the late eighteenth century movements that inspired such widespread trans-national mobilization had always been religious in nature, the most recent example being the rise of Protestantism in sixteenth century Western Europe and the political upheavals it produced. While succeeding movements of this type in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (democratic, nationalist, or socialist) were all secular in origin, they did share something in common with similar earlier religious movements. Like their predecessors, they were future-oriented, proclaiming the promise of a new and better world once the corrupt old one was swept away. Whether religious or secular, all promised their followers an idealized future in which sacrifice today would be redeemed in a better tomorrow.

By contrast, the Islamic State is backward-looking. Instead of calling for sacrifice to create a new future utopia, it seeks to revive a structure long dead—the Islamic caliphate—interpreting it as the lost Muslim ideal that can be restored only by using past Islamic precedents as a strict template. No policy, law, or political strategy can be deemed legitimate unless it is grounded in the institutions and examples provided by the early Muslim state and its divinely guided leaders. In this process the Islamic State rejects the structure of the modern nation state system and seeks to replace it with a universal empire of religion, announcing that all existing state structures lose their legitimacy upon the arrival of the caliphate: “The legality of all emirates, groups, states, and organizations, becomes null by the expansion of the khilāfah’s authority and arrival of its troops to their areas.”3 Like similar religious movements in the past, it promises its followers either ultimate victory or the consolation of bringing the world itself to an end in a fiery apocalypse.

While literature on the caliphate is enormous, not enough attention has been paid to its recent re-creation as a variety of secondary imperial state formation in which the trappings and ideologies of long lost empires are used as a political tool to build a new one. Such “empires of nostalgia” draw on a strong cultural tradition of a perceived golden age that can be reclaimed now or in the near future. Only one of many types of secondary empire, empires of nostalgia have a distinct form that is rooted in very deep and specific cultural traditions whose appeal is usually a mystery to those who do not share it. Further, in the twenty-first century the Islamic State is not alone in appealing to nostalgia for vanished empires. In the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse, Vladimir Putin now portrays Russia as the beleaguered defender of an Eastern Orthodox religious legacy inherited from the Byzantines, appealing to a peculiarly Russian cultural ethos that undergirds it. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has taken to reviving an appeal to the memory of the Ottoman Empire that the founders of Turkish Republic abolished and buried. The Communist Party heirs to Mao’s radical assaults on traditional Chinese culture now have a string of worldwide Confucius Institutes to market these formerly attacked values worldwide. Both empires and nostalgia are thus worth a closer look.

A world of empires: primary and secondary

Until the end of the First World War, empires were the most complex and dominant form of political organization in Eurasia, and had been so for more than two millennia. They had two distinctive forms that had different origins: large primary empires that that were self-generating and self-supporting, and smaller (in territory or population) secondary empires that emerged in response to them. In some cases, overly successful secondary empires transformed themselves by evolving into primary ones, usually through campaigns of conquest and incorporation into a larger hybrid system.

Primary empires were states established by conquest that had sovereignty over continental- or subcontinental-sized territories that incorporated millions or tens of millions of people into a unified and centralized administrative system.4 They financed themselves largely from internal resources through systems of direct taxation or tribute payments derived from their component parts. They maintained large and permanent military forces to protect marked frontiers and preserve internal order. Historically, primary empires were one or two orders of magnitude larger in territory and population than rival polities that (if they avoided incorporation) lived on their margins: regional kingdoms, city-states, or tribal confederations. Classic examples from Eurasia included the many empires that united China (Qin, Han, Tang, Ming, and Qing dynasties) over the course of two millennia,5 the Roman and Byzantine Empires that long dominated the Mediterranean basin,6 and the many iterations of the Persian Empire and its successor states on the Iranian Plateau and Central Asia.7

After the rise of Islam, the caliphate became a huge primary empire that ran from Spain and North Africa through the Arab Middle East and beyond into the Iranian Plateau and Central Asia.8 Upon its breakup, successor primary empires eventually appeared in what had become the Islamic world. The largest and most long-lasting was the Ottoman Empire that first emerged in the thirteenth century and by the eighteenth ruled from the Balkans to the borders of Iran, from the Caucasus to the Arabian Peninsula, Egypt, and parts of North Africa. But other significant and long-lasting empires in the Muslim world that emerged around the same time period were established by the Timurids in Central Asia, the Safavids in Iran, and the Mughals in India.9

Such primary empires may have begun with the hegemony of a single region or ethnic group, but they all became more cosmopolitan over time with the incorporation of new territories and people very different from themselves. Indeed, the main characteristic of a successful primary empire was its ability to thrive on diversity and make it a strength. An important aspect of its political structure, one that gave it great stability, was that the empire’s founding ruling elite could be replaced without bringing about the collapse of the state structure. Polities whose founding elites defined the state by their exclusive dominance of it lacked this capacity—they either had to limit the size of the state to one they could manage unaided, or risk its collapse at the hands of disaffected peoples whose own elites became permanent enemies of the state. The leaders of the early Islamic conquests experienced this tension firsthand when they broke away from a narrow conception of participation (Islam as a religion exclusive to the Arabs) to a strikingly diverse one (Islam as a world religion) in which all believers could potentially be part of a single political system in which there was an opportunity for a wide range of people to participate.

Empires were aided in this process by various types of long-term imperial projects designed to imprint particular aspects of their own cultural system on all peoples under their rule. It was not an attempt by the elite to create clones of themselves, but rather to foster a common core of values that would add to existing ones. It was a project that moved in stages from coercion and cooptation to cooperation and identification. It produced a vision of unity that extended well beyond force and created what we often identify as a civilization that long outlasted the political system that first produced it.

Examples include the use of Chinese ideographs and Confucian models of morality and governance in East Asia, or the survival of the use of Latin and Roman law and administration in the West. Religion could also prove a strong foundation for an imperial project in some parts of the world, as when the Romans and Byzantines began to see themselves as protectors and then missionaries for Christianity. Of course, the common use of the term “Islamic world” even today is a legacy of the founders of the caliphate whose project of making Muslim identity paramount over all others long survived that institution’s political collapse.

If classic primary empires were the product of internal development and sustained themselves through the exploitation of their own resources, there were also a large number of imperial polities that were the products of secondary empire formation. That is, they came into existence as a response to primary imperial state formation elsewhere. Although they often had tremendous power and influence, and mimicked primary empires in their actions and policies, they lacked most of their essential attributes. Most notably, they often exerted direct rule over relatively few people, even when their geographical scope was huge. But the common element that really set all of them apart from primary empires was the absence of an internal domestic resource base sufficient to support the polity, and a dependence on external resources to make up that deficiency. Secondary empires acquired these resources in various ways, but always from people and states they did not attempt to rule directly. They were thus “shadows” that took on the form and power of primary empires without all of their substance.

There were four different types of shadow empires:

Mirror empires that rose and fell in tandem with their rivals because they were responses to challenges presented by a neighbor’s imperial centralization. The best examples are the series of nomadic empires in Mongolia that emerged when China was unified under native Chinese dynasties.10 The danger China presented gave incentive for the nomads to unite, but these polities preserved themselves only by extracting resources from China, not by taxing their own people. Classic dyads included the Han/Xiongnu from 200 BCE to 200 CE and the Tang/Turks from 600–900 CE. When native Chinese dynasties collapsed, so did their nomadic counterparts that had become parasitically dependent on them.

Maritime trade empires that held the minimum amounts of territory needed to extract economic benefits from other polities that organized the production of the goods they traded. By focusing their investments on ports and strong navies, they attempted to control the means of exchange rather than the means of production. Examples include imperial Athens, Carthage, and Venice. In early modern times the Portuguese, Dutch, and British penetration of Asia took this form.11 They were vulnerable to rival naval powers but tended to be shattered only when existing land-based powers were strong enough to either destroy their trade networks or target their centers for elimination, as when Rome destroyed Carthage or the Spartans defeated the Athenians in the Peloponnesian War.

Vulture empires that were created by leaders of frontier provinces or client states who turned the tables on their erstwhile imperial masters in times of political and economic distress by seizing control of parts of the old empires. They characteristically sought to adopt the cultural values and administrative structures of the primary empires they occupied rather than impose new ones. Although their systems of governance were less sophisticated than the imperial systems they replaced, the ability to preserve order in the midst of anarchy gave them a competitive advantage. Ironically, the more successful they proved to be at restoring order, the more they undermined the rationale for their rule. They historically lost power when the structure of the old regime and its indigenous elites recovered enough to exclude the interlopers. Examples of such vulture empires include most of the many foreign dynasties that ruled north China,12 or the Nubians who briefly ruled ancient Egypt.13 In other cases, vulture empires emerged as masters of weak secondary imperial polities that lay beyond the reach of bigger primary empires. These shadow empires, such as the Hapsburg dynasty in Central Europe or the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in Eastern Europe, incorporated neighboring marginal territories but never produced an overwhelmingly strong center to unify them.14

Empires of nostalgia were based on the remembrance of organizations past. They claimed an imperial tradition and the outward trappings of an extinct empire, but could not themselves meet the basic requirements of an imperial state such as direct control of territory, true centralized rule, or significant urban centers. Indeed, they often lacked the territorial size or population to justify their pretensions—as when rulers of former provinces of an old empire promoted themselves to imperial rank. Examples include the medieval Carolingian Empire established by Charlemagne and its long-lived successor, the Holy Roman Empire. 15 As Voltaire acerbically complained, the “agglomeration that was called and which still calls itself the Holy Roman Empire is neither Holy, nor Roman, nor an Empire,”16 yet it survived as an institution for one thousand years.17 No better definition of a shadow empire of nostalgia could be had. As we will see, the caliphate has had a similar hold on the Islamic imagination.

Shadow empires in each of these categories could on some occasions evolve into true primary empires. The Mongol Empire founded by Genghis Khan in 1206 began like other mirror nomadic empires seeking only to extort northern China but ended up conquering it, and most of Eurasia as well, to become the largest land empire in history under his successors.18 Few maritime empires successfully moved to directly rule the lands they exploited economically, but the expansion of the British in India from a group of private armed traders in the seventeenth century to rulers of the whole subcontinent in the mid-nineteenth is an example of how it could be done.19 And while most vulture dynasties that ruled north China were never able to expand very far south, in 1644 the Manchu Qing dynasty did—quickly moving from vultures to become primary imperial rulers of all China for the next two-and-a-half centuries.20 When secondary empires did transform themselves into primary ones, however, the legacy of their earlier experiences as outsiders often profoundly affected how they saw the world. Unlike native Chinese rulers like the Ming dynasty it succeeded, for example, the Qing treated non-Han peoples as potential partners to be co-opted rather than inveterate enemies to be walled off.21 In South Asia, even after their de facto displacement of the Mughals and other powerful Indian states, the British were loath to take on the formal responsibilities of governance, and never lost their mercantile preoccupations that put profit first. Only after various forms of indirect rule failed and put their position in India at risk during the so-called Sepoy Rebellion of 1857 did the British government in London finally end the East India Company’s responsibility for administration there.22

Empires of nostalgia and cultural memory

Of all the shadow empires, those based on nostalgia are perhaps the most unusual and the most shadowy. They exist only in the minds of those who perceive them and are rooted in conceptions of empires past that never truly existed in the ideal forms that were attributed to them. Their origins were firmly rooted in the lasting cultural memory left by powerful empires on the regions and peoples they ruled or bordered. When these empires collapsed (particularly if that collapse resulted in many generations of political anarchy, population decline, and economic decay), the extinct imperial structure was often imbued with the aura of a former “golden age” now lost.

The memory of this empire and its trappings retained such an ideological hold over future generations that it could be used as a powerful tool in later times when new rulers sought to build states or empires of their own. It also provided many of them with templates for building a large-scale administration where these had disappeared. This tendency was strongest in China where the cosmological myth of a necessary emperor ruling “All under Heaven” emerged even before it was fully united, and later provided the impetus to recreate a united empire after it was lost.23 Any conquerors who could reunite China after a period of disunion—even “barbarians” like the Mongols and Manchus—were deemed legitimate if they succeeded.24 The founding myth of unity that came into being with the first Qin emperor in the third century BCE was so strong that (unlike in the West) primary empires succeeded in reuniting China after each period of state collapse. (Some today would see the People’s Republic of China as the latest in this series of unified Chinese states attempting to restore its former status as the dominant power in East Asia.)

China’s success in recreating imperial unity after collapse (periods that often spanned many centuries) was the exception rather than the rule, however. In most places the dream of reestablishing a primary empire in its past form always remained a distant hope rather than an achievable reality. Still, the very idea of the old empire provided an ideological basis for those leaders seeking to centralize power against the opposition of powerful local elites. Charlemagne’s Carolingian Empire fell squarely into this category because it lacked most of the basic necessities of state formation, let alone empire formation. Early medieval Europe lacked big urban centers and an integrated economy. Its rulers could raise only rudimentary taxes and relied on feudal troop levies rather than standing armies. Indeed, the entire feudal system of land grants run by autonomous local notables was antithetical to Roman principles of imperial rule. These continued only in the Roman Catholic Church, whose hierarchical clergy and institutional ownership of land far better reflected a Roman imperial template.25

Still, it was recognized as an empire at the time, and continues to hold an outsized place in medieval European history. Why? Because it was the first widely accepted attempt to bring back the political model of Rome to the Catholic Christian West, and it struck a powerful cultural chord in regions that saw themselves as falling far below the level of civilization that had once existed. It would serve as a potent ideological weapon in the (ultimately unsuccessful) drive to centralize the petty states of feudal Europe into a single imperial polity, as well as later giving Western Europe an imperial vision of itself in dealing with the Islamic world during the Crusades.26 It had far less of an impact in the territories of the Eastern Roman Empire where the Byzantines (allied with the Eastern Orthodox Christian Church) successfully maintained a unified imperial structure and centralized military for a millennium after its collapse in the West.27

In empires of nostalgia, rulers tied their own legitimacy to something that no longer existed but still attracted willing participation: the desire to be part of a political project that inspired hope of better things to come by appealing to past glory. Petty struggles for power and supremacy could be dressed in more attractive clothing and tied to loftier goals that had strong cultural appeal. Cooperation was thus easier to achieve, and recognition of the new ruler and his state as more legitimate, if it could be linked to an admired (if long gone) empire rather than being viewed as an unwelcome innovation imposed by a usurping power-hungry clique.

Because empires of nostalgia draw their power from the realm of cultural memory, they do not travel well. The West’s infatuation with ancient Rome has little resonance in China, nor does the epic rise and fall of Chinese dynasties stir any emotion in the West. Yet in their own realms, such remembrances of empires past can be tenacious. Indeed, it appears the only way to kill the nostalgia for one is to inculcate a new cultural order. While the model of Rome remained strong in the West, it was lost to Roman North Africa after the Islamic conquest. From that point on, people there were invested in empires of nostalgia drawn from the Islamic tradition. Few were more potent than the idea of the caliphate.

The caliphate and its new incarnations

The most powerful empire of nostalgia in the Islamic world has always been the caliphate. Seen as a framework for governance sanctified by the Prophet and his immediate successors that began in the mid-seventh century CE, its early conquests were spectacularly successful. They laid the groundwork not only for a new imperial structure but one uniquely combining the Muslim religion and the state. Like most empires, its internal politics were fractious and not very edifying for either those who fell victim to them or later historians. Even as the empire expanded externally, it was divided by civil wars over who should rule the caliphate. The Umayyad Caliphate displaced those who were supporters of the heirs of the Prophet’s son-in-law ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib (who maintained a distinct identity as Shi’ites). The Umayyads ruled the caliphate until 750 when they were displaced by the Abbasids. The Abbasids consolidated their power in part by murdering all the Umayyad pretenders they could find. Despite its bloody beginnings, the Abbasid dynasty marked the highpoint of caliphal power and has long been viewed as the period of Islam’s greatest influence culturally and politically. Its power declined in the mid-ninth century when it lost control of outlying territories and was challenged by many rebellions. The dynasty lost secular authority when conquered by new regional dynasties, beginning with the Buyids from Iran in 945. However, the prestige of the caliphate was so high that all succeeding Muslim dynasties acknowledged the caliph’s spiritual authority. The caliphate ended when the Mongols sacked Baghdad in 1258 and murdered the last caliph, abolishing the institution. Coming from a different cultural tradition, they had no particular respect or sympathy for Islamic institutions (although their descendants who stayed would eventually adopt the religion).28 The Ottoman sultans, who first took up the title for themselves in the fourteenth century, began to stress the importance of the institution for their own legitimacy beginning in the eighteenth century, in a fairly successful bid to portray themselves as defenders of Islam against the growing power of Christian Europe.

While appeals to an idealized Islamic past had a long history, particularly in the battle to throw off European colonial domination in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Islam as a framework for statebuilding had seemingly lost the battle of ideas to Western democratic, nationalist, or socialist movements that either rejected religion outright or reduced its writ to the private sphere. Such secular movements all sought to build ideal human societies of some sort and saw religion (of whatever type) as an obstacle to achieving their goals. Beginning first with the American and French revolutions in the late eighteenth century, religious institutions in the West were stripped of any privileged political role even in countries like Britain that still recognized a state religion. During the twentieth century, socialist states like the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China attacked religious belief and religious institutions directly, proclaiming atheism as national policy. Following the end of World War I, most leaders of newly independent states in Muslim majority countries (or those seeking independence) similarly grounded their political legitimacy in a variety of secular rather than religious guises: nationalism, kingship, democracy, or radical socialism.

This can be seen most strongly among the secular nationalists who established all the regimes of the Arab world following the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire (save Saudi Arabia). They viewed religion more as a source of the region’s weakness rather than strength, and believed it needed to be cast aside to build state power. Non-Arab Muslim polities adopted similar policies of state secularism in pursuit of national development. In the 1920s, it was the core ideology of Turkey’s Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who abolished the caliphate in 1924 during his successful drive to create a secular republic. Reza Shah Pahlavi attempted to modernize his country by stressing Iran’s pre-Islamic greatness under the Persian Empire. Even in distant Afghanistan, King Amanullah Khan spent the 1920s attempting to replace a legal system based on Islamic law with secular courts employing a secular law code. A British Indian political agent at the time went so far as to conclude that the rise of secular modernist reformers was “an illustration of the broad fact already noticed that the impulse behind recent movements in the East is nationalist rather than religious in character, and that when the two forces come into conflict the advantage lies with the nationalist.”29

Almost a century later, this conclusion appears to have been premature. Beginning with the Iranian revolution in 1979, the Islamic world has been swept by a revival of religious political movements in which the secular nationalists have been at a clear disadvantage. But the form such Islamic movements has taken has varied significantly. Some Sunni Muslim Brotherhood followers saw their movement as able to work within the structures of existing secular states, with the expectation of moving them toward such religious goals as the implementation of shari’ah law. Others sought to implement purely Islamic governments with no inclination to share power. In Shi’ite Iran, clerics set the rules of the Islamic Republic and oversaw its management. In the Sunni world, Mullah Omar, the Taliban leader of Afghanistan, proclaimed the country an independent Islamic emirate and gave himself the title of amīr al-muʾminīn (Commander of the Faithful) in 1996. Notably, however, he did not proclaim himself caliph, or suggest that the Afghan emirate marked the beginning of a new caliphate. In this he appears to have been following Al-Qa’idah opinion that a caliphate could only come into existence after the lands of the original caliphate (including places no longer Muslim, like Spain) had come under its control. Significantly, Mullah Omar was neither an Arab nor from the Prophet’s tribe, qualifications historically deemed necessary for becoming a caliph (although these criteria had not applied during the many centuries when the Ottoman Turkish sultans claimed the title).30

The shift of the concept of the caliphate from some future culminating endpoint that would emerge only after Islam’s final victory over its rivals to a contemporary institution designed to bring that victory became manifest in June 2014. At that time, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) endorsed Abū Bakr al-Baghdādī’s declaration of himself as caliph in the territories ISIS occupied. In sharp contrast to Mullah Omar, Baghdādī is both an Arab and a descendant of the Prophet’s tribe of Quraysh. The large number of Muslim supporters, including thousands of foreign fighters and even women, who have flocked to join in the fight for this new caliphate has surprised many observers. Their enthusiasm for participating in a fight that is not their own is best explained by viewing the Islamic State and its declared caliphate as an “empire of nostalgia” that attracts precisely because it is an attempt to recreate a lost empire of glory when Muslims were politically and culturally dominant.

The original caliphate was a transnational empire, so those attempting to revive it now see themselves as legitimate in reaching out to the entire Muslim ummah for support. Like other purveyors of empires of nostalgia, however, its culturally resonant project is based on illusions designed to soften a harsher reality. The war the Islamic State portrays as a noble and attractive struggle pitting believers against unbelievers to create an ideal Islamic state is in reality a vicious civil war conflict within the Muslim community. Only by declaring its equally Muslim opponents (albeit of different sects or political factions) kuffār or infidels, apostates worthy of death (that is, takfīrThe act of one Muslim asserting that another Muslim, on the basis of beliefs or actions, is actually not a Muslim but rather an infidel (kāfir).), can the new caliphate justify its brutal tactics that bring mass slaughter and oppression to the heartland of the old caliphate.

In this, ISIS lays the foundation for its demise: successful empires succeed by tempering their violence through the accommodation of diversity. Power may be won by the sword, but it is maintained by softer means. As conquerors of large non-Muslim communities, rulers of the early caliphate needed to accommodate indigenous groups and accepted them as long as they accepted the caliphate’s rule and paid taxes. By contrast, the current Islamic State works in an environment in which Muslim communities constitute the vast majority. Ironically, some Christian communities have received better protection that their Muslim neighbors because the original caliphate granted them specific protections not shared by other religions (such as the Yazidis) or those fellow Muslims they have deemed heretical.31 By defining its caliphate so narrowly, they risk the fate of similar radical Islamic movements such as the seventh-century Kharijites, who also viewed most other Muslims as enemy apostates. They were marginalized and destroyed by unified opposition to them in both the Sunni and Shi’ah communities.

Of all the varieties of shadow empires, an empire of nostalgia is least likely to make the transition into a primary empire. Even in China where new dynasties grounded themselves in older imperial traditions, that transition was only the finishing touch that transformed conquering rebels and foreign invaders into legitimate rulers. In this they resemble what anthropologists call revitalization movements whose charismatic leaders seek to bring about a social transformation of the world that would empower their followers.32 To attempt the recreation of an old imperial structure on the ground, however, invites attack by rivals of all sorts that few such movements could withstand. Empires of nostalgia thus do best in a world where there are no powerful state rivals, in times when long periods of political turmoil produce a desire for order even where it cannot be delivered. Where strong states do exist, such movements are almost always destroyed as autonomous political entities, a prospect that often leads to the belief that divine intervention will save the day, as the ISIS Caliphate’s English-language media mouthpiece asserts. Called Dabiq, it is named for the site in northern Syria where some believe the Muslim version of Armageddon will occur.

About the author

Thomas Barfield is an anthropologist who received his Ph.D. from Harvard University. He conducted ethnographic fieldwork with nomads in northern Afghanistan in the mid-1970s and is author of The Central Asian Arabs of Afghanistan (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1981); The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China (Oxford: Blackwell, 1989); and co-author (with Albert Szabo) of Afghanistan: An Atlas of Indigenous Domestic Architecture (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1991). Professor of Anthropology at Boston University, Barfield is also President of the American Institute for Afghanistan Studies. In 2007 Barfield received a Guggenheim Fellowship that supported the research for his most recent book, Afghanistan: A Cultural and Political History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010).

Notes

All digital content cited in this article was accessed on or before September 21, 2016.

[1] The Islamic State’s official declaration of its establishment of a caliphate was published in a number of languages as “This is the Promise of Allah,” Al Hayat Media Center, June 29, 2014 (https://ia902505.us.archive.org/28/items/poa_25984/EN.pdf), 6.

[2] Alexis de Tocqueville, The Old Regime and the Revolution, trans. John Bonner (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1856), 27.

[3] “This is the Promise of Allah,” 5.

[4] This and subsequent sections pf this article are taken directly from Thomas J. Barfield, “The Shadow Empires: Imperial State Formation along the Chinese-Nomad Frontier,” in Susan E. Alcock, Terence N. D’Altroy, Kathleen D. Morrison, and Carla M. Sinopoli (eds.), Empires: Perspectives from Archeology and History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 21–41.

[5] See Part 1 of John King Fairbank and Merle Goldman, China: A New History (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2006).

[6] Edward Gibbon, History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (3 vols., New York: Modern Library, 1984).

[7] Touraj Daryaee (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

[8] Marshall G. S. Hodgson, The Venture of Islam: Conscience and History in a World Civilization, Vol. 1: The Classical Age of Islam (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974).

[9] Stephen Dale, The Muslim Empires of the Ottomans, Safavids, and Mughals (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

[10] Thomas Barfield, “The Hsiung-nu Imperial Confederacy: Organization and Foreign Policy,” Journal of Asian Studies 41(1981): 45–61.

[11] Sanjay Subrahmanyam, “Written on Water: Designs and Dynamics in the Portuguese Estado da Índia,” in Alcock et al. (eds.), Empires, 42–69.

[12] Thomas Barfield, The Perilous Frontier (Oxford: Blackwell, 1989), Chapters 3, 5, and 7.

[13] Robert Morkot, “Egypt and Nubia,” in Alcock et al. (eds.), Empires, 227–251.

[14] Zenonas Norkus, “The Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the Retrospective of Comparative Historical Sociology of Empires,” World Political Science Review 3 (2007), 1–41 (http://www.fsf.vu.lt/users/zennor/pub/NorkusWorldPoliticalScienceReview.pdf), 4.

[15] John Moreland, “The Carolingian Empire: Rome Reborn?,” in Alcock et al., Empires, 392–418.

[16] Voltaire, Essai sur les mœurs et l’esprit des nations et sur les principaux faits de l’histoire depuis Charlemagne jusqu’à Louis XIII (2 vols.; Paris: Garnier frères, 1963), 1.683.

[17] Peter H. Wilson, Heart of Europe: A History of the Holy Roman Empire (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press, 2016).

[18] David Morgan, The Mongols (Oxford: Blackwell, 1990).

[19] Jeremy Black, The British Seaborne Empire (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004).

[20] Jonathan D. Spence and John E. Wills (eds.), From Ming to Ch’ing: Conquest, Region, and Continuity in Seventeenth-Century China (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979).

[21] William T. Rowe, China’s Last Empire: The Great Qing (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009).

[22] Philip Lawson, The East India Company: A History (London: Longman, 1993).

[23] Robin Yates, “Cosmos, Central Authority, and Communities in the Early Chinese Empire,” in Alcock et al., Empires, 351–368.

[24] Hok-Lam Chan, Legitimation in Imperial China: Discussions Under the Jurchen-Chin Dynasty (1115–1234) (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1984).

[25] Moreland, “The Carolingian Empire: Rome Reborn?”

[26] Anne A. Latowsky, Emperor of the World: Charlemagne and the Construction of Imperial Authority, 800–1229 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013).

[27] Edward Luttwak, The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009).

[28] Or for any other religious institutions that stood in the way of conquest. A generation earlier, the Mongols had threatened the Pope in Rome in the same manner as they did the caliph, but he was spared by a fortuitous withdrawal of their army to Mongolia before they could carry out his destruction. In the Near East, they fought a war of extermination against the so-called Assassins, an Islamic sect whose descendants became the Isma’ili followers of the Aga Khan.

[29] Senzil K. Nawid, Religious Response to Social Change in Afghanistan, 1919–29: King Aman-Allah and the Afghan Ulama (Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 1999), 52.

[30] Reza Pankhurst, The Inevitable Caliphate?: A History of the Struggle for Global Islamic Union, 1924 to the Present (London: Hurst, 2013).

[31] Jacob Marcus, The Jew in the Medieval World: A Sourcebook, 315–1791 (New York: Jewish Publication Society, 1938), 13–15; Adam Hoffman and Rachel Hoffman, “ISIS and the Implementation of Islamic Rule,” TonyBlairFaithFoundation, August 27, 2014.

[32] Anthony F. C. Wallace, “Revitalization Movements,” American Anthropologist 58 (1956): 264–281.