PDF

Download

Citations

Click and drag then release to select a passage to cite.

Annotations

How to submit annotations to Mizan Journal articles:

your work is published.

Search within

A Comparative Approach to the Medieval Theory of Authorship

Image

Audio

Video

Chart or Graph

A Comparative Approach to the Medieval Theory of Authorship

This paper was presented in the Panel “Premodern Fables and Ambivalent Authorship: Interlocutors, Copyists, and Creative Redactors” at the Fourteenth Biennial Iranian Studies Conference held at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), in Mexico City, Mexico. The paper elaborates a previous study on medieval authorship in premodern fables (Yamanaka 2018). The focus is on how authorship—or “authority,” rather—is presented and defended in compilations of “marvels”.

Marvels and fables are analogous but not the same. Both are narrative compilations of that are usually not too long and comprise entertaining and didactic components. Animals, plants, and natural phenomena feature in many of them. But they serve different purposes. The one is encyclopaedic and seeks knowledge, while the other is allegorical and seeks wisdom. One inspires curiosity, the other instils moral lessons. However, examining narrative strategies of authors and compilers of medieval books of marvels may offer some insight into medieval authorship from a different angle.

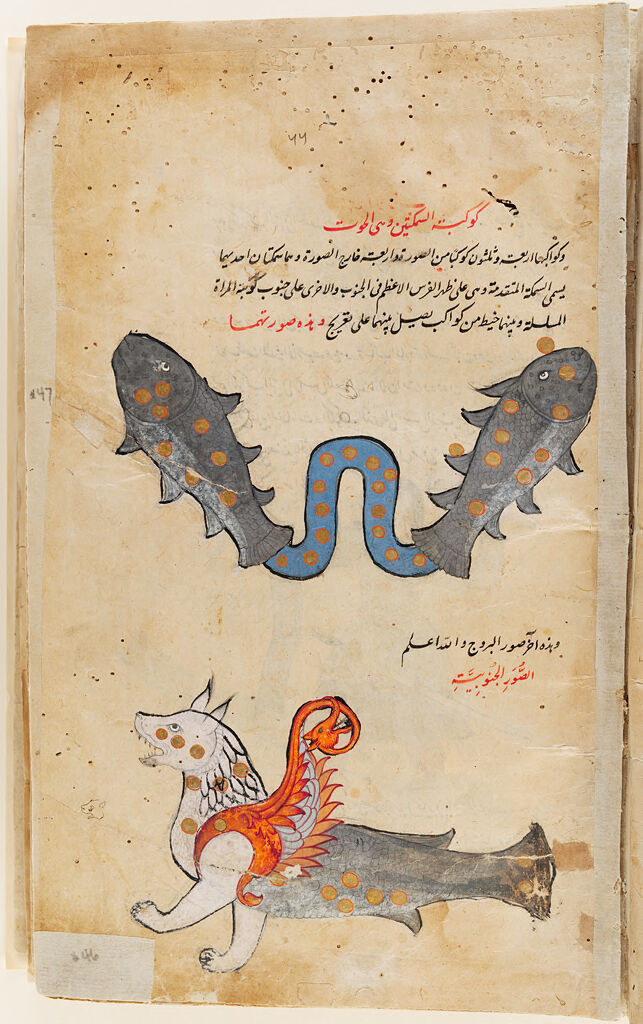

Manuscript of the ‘Aja’ib al-makhluqat (Wonders of Creation) of Qazwini, folio 36 recto, c. 1650-1700. Public domain image via Harvard Art Museums.

Marvels — that is to say, descriptions of curious beings and phenomena at the borders of the then known world — were an important component in encyclopaedic compilations of knowledge about the human and material world in the Islamicate world, as well as in many other cultures. Marvels were believed to be part of the natural order. However, tales that inspired a sense of wonder often also provoked doubt and skepticism. Authors or compilers of books of marvels thus felt a need to defend and legitimize the extraordinary in the prefaces to their works. In this paper, we examine the prefaces of two specimens of Arabic and Persian ʿajāʾib writing, namely the Arabic Tuḥfat al-albāb wa-nukhbat al-iʿjāb (A Gift to the Minds and a Choice of Wonders) by Abū Ḥāmid al-Gharnāṭī (473–565/1080–1169/70), and ʿAjāyib al-makhlūqāt va gharāyib al-maujūdāt (Marvels of Things Created and the Curiosity of Things Existing), a late sixth/twelfth-century Persian encyclopedia by Muḥammad Ṭūsī. We examine the motives behind marvel narratives and explore several of the narratological techniques that the authors or compilers use to establish credibility and authority for their work.

Because encyclopedic works largely consist of information gathered from earlier sources, they might not be considered “authorial compositions” in the narrow, modern sense. This prompts a Foucauldian question about the role of the “author” in medieval Arabic and Persian literature—a question best examined within its historical context, much like Alastair Minnis has done for medieval European literature. Minnis’s studies on the concept of auctor—meaning both “author” and “authority” as a trusted source of information—and on the role of the compilator in medieval European texts offer valuable insights for our analysis.

The authenticity of information about regarding curious things that readers had neither seen nor heard of, seems to have been a critical concern for the authors of such works, as can be seen in the defence, or apologia, that each wrote to pre-empt any accusation of falsehood or fabrication.

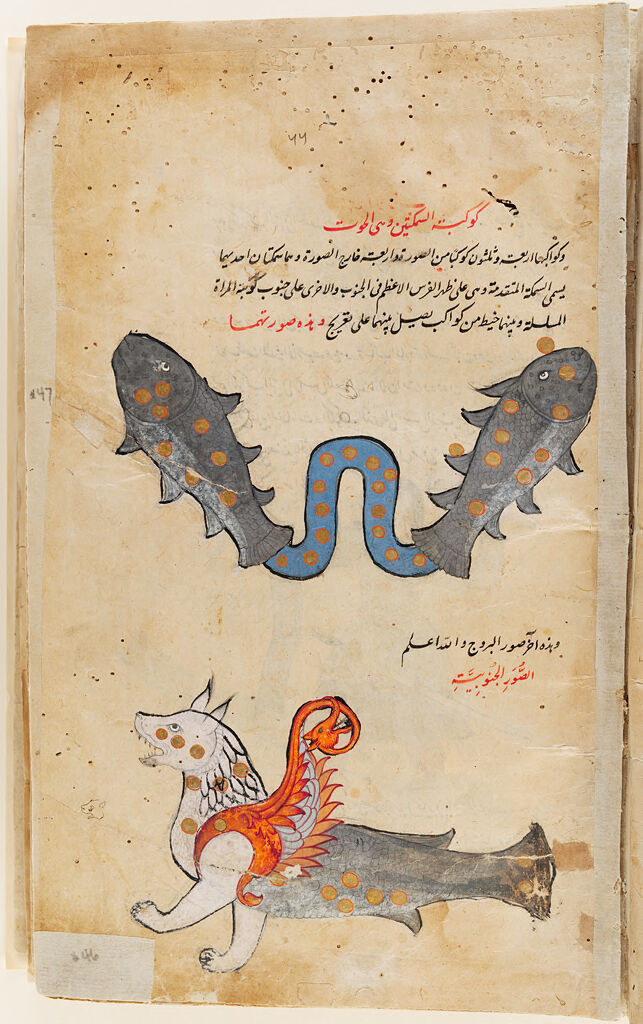

Two Winged Angels, Folio from a Manuscript of Al-Qazwini’s ‘Aja’ib al-makhluqat. Public domain image made available by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, via Wikimedia Commons

The first preface we examine is from the Tuḥfat al-albāb wa-nukhbat al-iʿjāb (ca. 557/1162) by Abū Ḥāmid al-Gharnāṭī, who was born in Granada in 473/1080, travelled through Central Asia and Central Europe, and died in Damascus in 565/1169-70. In the opening passages of his book, which includes accounts of the wonderful things he has seen during his travels, al-Gharnāṭī praises god:

Praise be to Allah who …in the regions of the earth brought to existence wonders of creation for which imaginative powers are exhausted in order to enumerate, assess, give form, and define […]

Evidently, al-Gharnāṭī’s notion of “wonder” is that such things are part of God’s creation and his approach to them is “encyclopedic,” that is, the wonders shall be enumerated, assessed, given form, and defined. He further insists:

If a rational person (al-ʿāqil) hears about a conceivable marvel (ʿajaban jāʾizan), he would consider it correct and would not deny it as a lie or condemn it as incorrect. Whereas if an ignorant person (al-jāhil) hears about what he has not witnessed, he would accuse the speaker as a liar and a forger. For he lacks reason and is limited in education. […]

Do not deny things of which you do not know the hidden meaning. Almighty Allah said: “Rather, they have denied that which they encompass not in knowledge and whose interpretation has not yet come to them.” (Quran: Yunus 39) What we want to present here is that one must be weary of the fact that humans hasten to deny what they have not witnessed themselves thus being afflicted by the blame for his lack of knowledge.

In this apologia, al-Gharnāṭī defends his accounts of marvels which he has seen or heard about himself, arguing that some marvels are rationally “conceivable” and should not be hastily dismissed as falsehoods. Quoting from the Qurʾān, al-Gharnāṭī insists that disbelief and denial of marvelous things can only be a sign of one’s ignorance and lack of education. He appeals to his readers’ “rationality” to legitimize his accounts, while his extensive travels and firsthand experiences lend credibility to much of his reporting. At the same time, by urging readers to remain humble before Allāh’s creative power, he subtly distances himself from full responsibility for the accuracy of his information.

Muḥammad Ṭūsī, a near contemporary of al-Gharnāṭī, is the author of the ʿAjāyib al-makhlūqāt va gharāyib al-maujūdāt, a cosmographic-cum-encyclopaedic work in Persian dedicated to the Seljuqid sultan Ṭughril III and compiled sometime during his reign (571-90/1175-94). The work consists of a preface and ten chapters: 1) celestial bodies; 2) phenomena between the heavens and the earth; 3) earth, waters, mountains; 4) cities; 5) trees and plants; 6) images and tombs; 7) human races; 8) jinn and shayṭān; 9) birds; 10) animals.

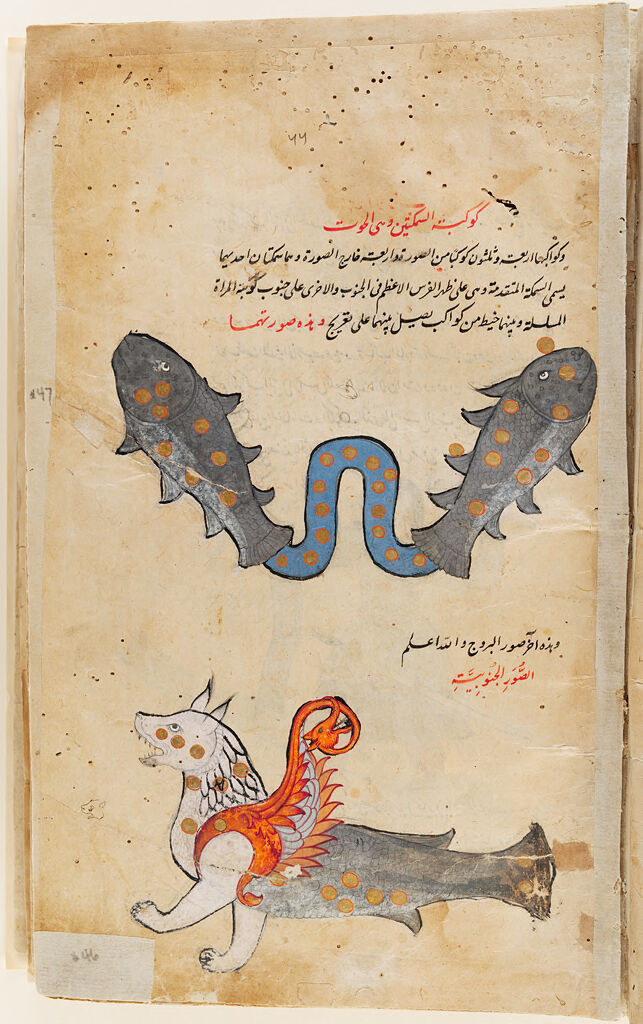

[Incomplete manuscript of the Ottoman Turkish translation of ʻAjāʼib al-makhlūqāt of Qazwīnī], Image 226. Image made available via the Library of Congress.

After composing many works in every branch of knowledge, in Arabic and in Persian, we thought that nothing would be better than to write this book. It would allow its reader to discover all the wonders of the world and curiosities of this age (ʿajāyib-i jahān va gharāyib-i zamān), without having to wander the limits and the borders of the earth or to cover the plains and the seas. The reader would come to know how many types of creations the Exalted God has created, and upon which people God looked favorably, or upon which people His fury released the wind of fortune. Since this wish is fulfilled (only) by travelers such as Alexander who explored the earth and Jesus son of Maria who toured the horizons …

He further writes:

[…] We composed this book (mā īn kitāb-rā taʾlīf kardīm) since most people do not possess resources to roam the world. So that the reader can see things that he has not seen (tā ānchi nadīd bibīnad). We shall endeavour to describe (raqm kunīm) the appearances of the marvels of the world that people have hitherto seen and heard of. And we shall entitle [the book] Marvels of Things Created and the Curiosity of Things Existing, so that people can read it and know the work of God and contemplate …

Here the author is presenting the utilitas, or the usefulness of the book, his modus procedendi, the mode of proceeding, and the titulus libri, its title. He presents his book as a portrayal of the world and all of God’s creations, intended for those who cannot journey to the farthest reaches of the earth, unlike Alexander or Jesus, whom he regards as ultimate explorers. He asserts that he describes the forms and appearances (ṣuvar va ashkāl) of the marvels witnessed and heard of (ānchi dīda-and va shanīda) by these renowned travelers. Thus, Ṭūsī seems to be validating the authenticity of his information based on eye- (or ear-) witness accounts, but not his own first-hand information, as in the case of a traveler such as al-Gharnāṭī. Rather, he relies heavily on the auctoritas of the ancients. Alexander, indeed, seems to be one of the major auctores (authorities) for Ṭūsī. That Alexander is a significant presence as a witness of strange beings and things is attested in the high number of anecdotes or references to him: a total of fifty-nine to be precise, which is more than the number of anecdotes attributed to Solomon or the Prophet Muḥammad in his book.

Ṭūsī seems to consider the main utility of the book to be its presentation of images through descriptions that would help readers “visualize” marvels. It is likely that these textual descriptions were accompanied by visual illustrations even in the earliest manuscripts of the work. The descriptive texts often end with the expression: “And this is a picture of …” An emphasis on visualization can also be seen in the preface, where Ṭūsī likens his book to a “mirror” (āyina).

A passage in the preface tells a story about a strange dream that the author had as a child, in which he meets a woman who hands him a mirror in a world that is flooded. She tells him that the world is like a hungry serpent, devouring creations for a thousand years. Tūsī clarifies the meaning of the mirror in this dream, linking it to his intentio as follows:

The interpretation of the mirror is — and Allāh knows best — that it is something that shows you what you cannot see. We have composed this book as a “mirror,” to show you all the marvels of the world. The heavenly as well as the earthly have we described: castles, fortresses, cities and citadels of the lands and the seas.

Like al-Gharnāṭī, Ṭūsī also admonishes the reader not to deny something just because he has not seen it and stresses that perception of the “unknown” or “marvellous” is a relative matter:

[…] A person may not know about the marvels of his own city, thus it should not be strange if he does not know about other cities. In other words, it is not commendable to deny things, since even if someone has not seen a thing, it does not mean that others have not seen it either.

At the same time, Tūsī is mindful that not all information should be accepted uncritically. As compiler, he evaluates the authenticity of the information he has collected, ranking it based on truth value. In his preface, he explains that he has marked letters in the margins to rate the veracity of the information he is compiling. (Unfortunately, none of the extant manuscripts have the marks.)

ظ for ẓāhir (self-evident) > ex. heavens

بع for baʿīd (remote) > something that require proof

صد for ṣidq (authentic) > Qur‘ān, hadith

مع for maʿrūf (known) > accounts handed down repeatedly in books

شبه for shubhat (uncertain) > strange stories from travelers with no definite proof

By this classification, Ṭūsī is at least taking partial responsibility for the authenticity of the contents, while urging readers to withhold their judgement until verification.

How did authors, compilers, copyists, or creative redactors of books of wisdom, such as the Kalīla wa Dimna, develop their apologia, intentio, utilitas, and modus procedendi, in comparison? Were the qualities that were defended essentially different in books of knowledge and books of wisdom? What were their narrative strategies to achieve their goals? These are some questions that may open further discussions with the other essays collected in this issue. It would, for example, be interesting to probe the role of Alexander in the so-called “’Alī ibn Shāh” preface to Kalīla wa Dimna. Why is he mentioned in the back story to the compilation of this work?

Bibliography

Minnis, A. 1979. “Late-medieval discussions of compilatio and the rôle of the compilator.” Beiträge zur Geschichte der deutschen Sprache und Literatur 101:385–421.

———. 1988. Medieval theory of authorship: Scholastic literary attitudes in the later Middle Ages. 2nd ed.,,. Philadelphia

———. 2006. “Nolens auctor sed compilator reputari: The late-medieval discourse of compilation.” In La méthode critique au Moyen Âge, eds. M. Chazan and G. Dahan, 47–63. Turnhout.

Yamanaka, Y. “Authenticating the Incredible: Comparative Study of Narrative Strategies in Arabic and Persian ʿajāʾib Literature. Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 45 (2018): 303-353.

A Comparative Approach to the Medieval Theory of Authorship

This paper was presented in the Panel “Premodern Fables and Ambivalent Authorship: Interlocutors, Copyists, and Creative Redactors” at the Fourteenth Biennial Iranian Studies Conference held at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), in Mexico City, Mexico. The paper elaborates a previous study on medieval authorship in premodern fables (Yamanaka 2018). The focus is on how authorship—or “authority,” rather—is presented and defended in compilations of “marvels”.

Marvels and fables are analogous but not the same. Both are narrative compilations of that are usually not too long and comprise entertaining and didactic components. Animals, plants, and natural phenomena feature in many of them. But they serve different purposes. The one is encyclopaedic and seeks knowledge, while the other is allegorical and seeks wisdom. One inspires curiosity, the other instils moral lessons. However, examining narrative strategies of authors and compilers of medieval books of marvels may offer some insight into medieval authorship from a different angle.

Manuscript of the ‘Aja’ib al-makhluqat (Wonders of Creation) of Qazwini, folio 36 recto, c. 1650-1700. Public domain image via Harvard Art Museums.

Marvels — that is to say, descriptions of curious beings and phenomena at the borders of the then known world — were an important component in encyclopaedic compilations of knowledge about the human and material world in the Islamicate world, as well as in many other cultures. Marvels were believed to be part of the natural order. However, tales that inspired a sense of wonder often also provoked doubt and skepticism. Authors or compilers of books of marvels thus felt a need to defend and legitimize the extraordinary in the prefaces to their works. In this paper, we examine the prefaces of two specimens of Arabic and Persian ʿajāʾib writing, namely the Arabic Tuḥfat al-albāb wa-nukhbat al-iʿjāb (A Gift to the Minds and a Choice of Wonders) by Abū Ḥāmid al-Gharnāṭī (473–565/1080–1169/70), and ʿAjāyib al-makhlūqāt va gharāyib al-maujūdāt (Marvels of Things Created and the Curiosity of Things Existing), a late sixth/twelfth-century Persian encyclopedia by Muḥammad Ṭūsī. We examine the motives behind marvel narratives and explore several of the narratological techniques that the authors or compilers use to establish credibility and authority for their work.

Because encyclopedic works largely consist of information gathered from earlier sources, they might not be considered “authorial compositions” in the narrow, modern sense. This prompts a Foucauldian question about the role of the “author” in medieval Arabic and Persian literature—a question best examined within its historical context, much like Alastair Minnis has done for medieval European literature. Minnis’s studies on the concept of auctor—meaning both “author” and “authority” as a trusted source of information—and on the role of the compilator in medieval European texts offer valuable insights for our analysis.

The authenticity of information about regarding curious things that readers had neither seen nor heard of, seems to have been a critical concern for the authors of such works, as can be seen in the defence, or apologia, that each wrote to pre-empt any accusation of falsehood or fabrication.

Two Winged Angels, Folio from a Manuscript of Al-Qazwini’s ‘Aja’ib al-makhluqat. Public domain image made available by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, via Wikimedia Commons

The first preface we examine is from the Tuḥfat al-albāb wa-nukhbat al-iʿjāb (ca. 557/1162) by Abū Ḥāmid al-Gharnāṭī, who was born in Granada in 473/1080, travelled through Central Asia and Central Europe, and died in Damascus in 565/1169-70. In the opening passages of his book, which includes accounts of the wonderful things he has seen during his travels, al-Gharnāṭī praises god:

Praise be to Allah who …in the regions of the earth brought to existence wonders of creation for which imaginative powers are exhausted in order to enumerate, assess, give form, and define […]

Evidently, al-Gharnāṭī’s notion of “wonder” is that such things are part of God’s creation and his approach to them is “encyclopedic,” that is, the wonders shall be enumerated, assessed, given form, and defined. He further insists:

If a rational person (al-ʿāqil) hears about a conceivable marvel (ʿajaban jāʾizan), he would consider it correct and would not deny it as a lie or condemn it as incorrect. Whereas if an ignorant person (al-jāhil) hears about what he has not witnessed, he would accuse the speaker as a liar and a forger. For he lacks reason and is limited in education. […]

Do not deny things of which you do not know the hidden meaning. Almighty Allah said: “Rather, they have denied that which they encompass not in knowledge and whose interpretation has not yet come to them.” (Quran: Yunus 39) What we want to present here is that one must be weary of the fact that humans hasten to deny what they have not witnessed themselves thus being afflicted by the blame for his lack of knowledge.

In this apologia, al-Gharnāṭī defends his accounts of marvels which he has seen or heard about himself, arguing that some marvels are rationally “conceivable” and should not be hastily dismissed as falsehoods. Quoting from the Qurʾān, al-Gharnāṭī insists that disbelief and denial of marvelous things can only be a sign of one’s ignorance and lack of education. He appeals to his readers’ “rationality” to legitimize his accounts, while his extensive travels and firsthand experiences lend credibility to much of his reporting. At the same time, by urging readers to remain humble before Allāh’s creative power, he subtly distances himself from full responsibility for the accuracy of his information.

Muḥammad Ṭūsī, a near contemporary of al-Gharnāṭī, is the author of the ʿAjāyib al-makhlūqāt va gharāyib al-maujūdāt, a cosmographic-cum-encyclopaedic work in Persian dedicated to the Seljuqid sultan Ṭughril III and compiled sometime during his reign (571-90/1175-94). The work consists of a preface and ten chapters: 1) celestial bodies; 2) phenomena between the heavens and the earth; 3) earth, waters, mountains; 4) cities; 5) trees and plants; 6) images and tombs; 7) human races; 8) jinn and shayṭān; 9) birds; 10) animals.

[Incomplete manuscript of the Ottoman Turkish translation of ʻAjāʼib al-makhlūqāt of Qazwīnī], Image 226. Image made available via the Library of Congress.

After composing many works in every branch of knowledge, in Arabic and in Persian, we thought that nothing would be better than to write this book. It would allow its reader to discover all the wonders of the world and curiosities of this age (ʿajāyib-i jahān va gharāyib-i zamān), without having to wander the limits and the borders of the earth or to cover the plains and the seas. The reader would come to know how many types of creations the Exalted God has created, and upon which people God looked favorably, or upon which people His fury released the wind of fortune. Since this wish is fulfilled (only) by travelers such as Alexander who explored the earth and Jesus son of Maria who toured the horizons …

He further writes:

[…] We composed this book (mā īn kitāb-rā taʾlīf kardīm) since most people do not possess resources to roam the world. So that the reader can see things that he has not seen (tā ānchi nadīd bibīnad). We shall endeavour to describe (raqm kunīm) the appearances of the marvels of the world that people have hitherto seen and heard of. And we shall entitle [the book] Marvels of Things Created and the Curiosity of Things Existing, so that people can read it and know the work of God and contemplate …

Here the author is presenting the utilitas, or the usefulness of the book, his modus procedendi, the mode of proceeding, and the titulus libri, its title. He presents his book as a portrayal of the world and all of God’s creations, intended for those who cannot journey to the farthest reaches of the earth, unlike Alexander or Jesus, whom he regards as ultimate explorers. He asserts that he describes the forms and appearances (ṣuvar va ashkāl) of the marvels witnessed and heard of (ānchi dīda-and va shanīda) by these renowned travelers. Thus, Ṭūsī seems to be validating the authenticity of his information based on eye- (or ear-) witness accounts, but not his own first-hand information, as in the case of a traveler such as al-Gharnāṭī. Rather, he relies heavily on the auctoritas of the ancients. Alexander, indeed, seems to be one of the major auctores (authorities) for Ṭūsī. That Alexander is a significant presence as a witness of strange beings and things is attested in the high number of anecdotes or references to him: a total of fifty-nine to be precise, which is more than the number of anecdotes attributed to Solomon or the Prophet Muḥammad in his book.

Ṭūsī seems to consider the main utility of the book to be its presentation of images through descriptions that would help readers “visualize” marvels. It is likely that these textual descriptions were accompanied by visual illustrations even in the earliest manuscripts of the work. The descriptive texts often end with the expression: “And this is a picture of …” An emphasis on visualization can also be seen in the preface, where Ṭūsī likens his book to a “mirror” (āyina).

A passage in the preface tells a story about a strange dream that the author had as a child, in which he meets a woman who hands him a mirror in a world that is flooded. She tells him that the world is like a hungry serpent, devouring creations for a thousand years. Tūsī clarifies the meaning of the mirror in this dream, linking it to his intentio as follows:

The interpretation of the mirror is — and Allāh knows best — that it is something that shows you what you cannot see. We have composed this book as a “mirror,” to show you all the marvels of the world. The heavenly as well as the earthly have we described: castles, fortresses, cities and citadels of the lands and the seas.

Like al-Gharnāṭī, Ṭūsī also admonishes the reader not to deny something just because he has not seen it and stresses that perception of the “unknown” or “marvellous” is a relative matter:

[…] A person may not know about the marvels of his own city, thus it should not be strange if he does not know about other cities. In other words, it is not commendable to deny things, since even if someone has not seen a thing, it does not mean that others have not seen it either.

At the same time, Tūsī is mindful that not all information should be accepted uncritically. As compiler, he evaluates the authenticity of the information he has collected, ranking it based on truth value. In his preface, he explains that he has marked letters in the margins to rate the veracity of the information he is compiling. (Unfortunately, none of the extant manuscripts have the marks.)

ظ for ẓāhir (self-evident) > ex. heavens

بع for baʿīd (remote) > something that require proof

صد for ṣidq (authentic) > Qur‘ān, hadith

مع for maʿrūf (known) > accounts handed down repeatedly in books

شبه for shubhat (uncertain) > strange stories from travelers with no definite proof

By this classification, Ṭūsī is at least taking partial responsibility for the authenticity of the contents, while urging readers to withhold their judgement until verification.

How did authors, compilers, copyists, or creative redactors of books of wisdom, such as the Kalīla wa Dimna, develop their apologia, intentio, utilitas, and modus procedendi, in comparison? Were the qualities that were defended essentially different in books of knowledge and books of wisdom? What were their narrative strategies to achieve their goals? These are some questions that may open further discussions with the other essays collected in this issue. It would, for example, be interesting to probe the role of Alexander in the so-called “’Alī ibn Shāh” preface to Kalīla wa Dimna. Why is he mentioned in the back story to the compilation of this work?

Bibliography

Minnis, A. 1979. “Late-medieval discussions of compilatio and the rôle of the compilator.” Beiträge zur Geschichte der deutschen Sprache und Literatur 101:385–421.

———. 1988. Medieval theory of authorship: Scholastic literary attitudes in the later Middle Ages. 2nd ed.,,. Philadelphia

———. 2006. “Nolens auctor sed compilator reputari: The late-medieval discourse of compilation.” In La méthode critique au Moyen Âge, eds. M. Chazan and G. Dahan, 47–63. Turnhout.

Yamanaka, Y. “Authenticating the Incredible: Comparative Study of Narrative Strategies in Arabic and Persian ʿajāʾib Literature. Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 45 (2018): 303-353.