PDF

Download

Citations

Click and drag then release to select a passage to cite.

Annotations

How to submit annotations to Mizan Journal articles:

your work is published.

Search within

East LA: Center and Periphery in the Study of Late Antiquity and the New Irano-Talmudica

Image

Audio

Video

Chart or Graph

East LA: Center and Periphery in the Study of Late Antiquity and the New Irano-Talmudica

Introduction: expanding LA, expanding Sasanian Studies

This short essay grew out of a conference session that considered new perspectives on late antique Iran and Iraq.1 My contribution to this topic is entirely theoretical—which is to say I stay my philological hand—as I explore issues of center and periphery relating to geopolitical and religious facts on the ground during Late Antiquity, as well as the disciplinary terrain governing the study of Sasanian Iran. These thoughts are inspired by recent work that redraws the spatial and chronological limes of Late Antiquity, thereby bringing other religions and civilizations into the picture, particularly Islam.2 Here, I think through three overlapping interrelations—namely, Babylonian Jewry and the Sasanians, Babylonian and Palestinian rabbis, and the Sasanian and Roman Empires—and consider lessons learned from evaluating one set of dynamics alongside the others.

The effort to include Sasanian Studies within the purview of Late Antiquity can be compared with the expansion of Sasanian Studies to incorporate non-Iranian communities living in the empire, such as Babylonian Jewry. In both instances, scholarly interest has widened to include societies previously thought irrelevant to their areas of research, yet now recognized as significant factors, despite apparent spatial, chronological, linguistic, religious, and cultural differences. Such a reorientation comes with obvious benefits, and with some less obvious costs.

At its core, the growth of the study of Late Antiquity over the past half-century has itself been powered by a desire to correct a long-standing negative attitude towards this epoch, which had previously been seen as a time of decline and darkness.3 The establishment of Late Antiquity as an historical period worthy of study was crucial first and foremost for revisiting the history of the West, and particularly for better understanding how the Western world got from the classical age through the Middle Ages, and ultimately to the way we live now. It is just as important to consider the political and intellectual forces now expanding the chronological limes of Late Antiquity later, to include, say, early Islam, and its geographical borders eastward, to include Byzantium’s ever-present “other”—the Sasanian Empire. What do Late Antique Studies and Sasanian Studies have to gain here, and what do they have to lose?

The benefits for Sasanianists are clear. The study of Late Antiquity is flourishing, so tapping into this enthusiasm requires little justification. On more substantive grounds, there is a strong case to be made that the history of the Sasanian Empire is an integral part of the history of the Roman and Byzantine Empires. After all, the Sasanians saw themselves and their territories as interlinked with the Eastern Mediterranean.

At the same time, applying a late antique periodization initially driven by a particular set of factors to the Sasanian Empire can be disorienting and misleading. Parallels to key features of Late Antiquity in the West—such as Constantine’s adoption of Christianity—are either not present at all, or are at least less distinct, in Eastern Late Antiquity. Assuming that the Sasanian entanglement with Zoroastrianism is equivalent to the Christianization of Rome, or stating that Zoroastrianism had become the “state religion” of the Sasanians a la Christianity and the Roman Empire, might count as a “cost” of over-reading Sasanian history through the lens of Late Antiquity.4

“Late Antiquity,” Jewish Studies, and Israeli higher education

The phenomenon of Jewish Studies scholars reframing their work in terms of “Late Antiquity” is likewise worth pondering. For example: for some time, scholars in Jewish Studies have considered discarding the parochial term “the talmudic period” as a designation for the history of the Jews from the third to the seventh centuries CE, in favor of adopting the term “Late Antiquity” instead. Beyond mere semantics, what is lost and gained in this terminological shift?

As an illustration, a recent graduate program in late antiquity at the Hebrew University has struggled to define what “Late Antiquity” should mean in an academic context that, for obvious reasons, is far stronger in talmudic philology than, e.g., the study of Augustine. As with the example of Sasanian Studies, the question is again whether and how to adopt a periodization that was originally about the transition of the Greco-Roman classical world into the Middle Ages—where Jews and their history play, at most, a supporting role—to an academic context in which the story of the Jews is far less marginal. At times, the adoption of the paradigm of Late Antiquity in Jewish Studies and in Israeli higher education has been, more or less, seamless. In other instances, it has led to misrepresentations—in both directions. Thus, “Late Antiquity” has been uncritically presented as a self-evidently relevant periodization for Jewish Studies, while students in Israeli programs in Late Antiquity are perhaps insufficiently immersed in the “classical” sources and paradigms of Late Antiquity (at least as conventionally defined) to be able to intelligently converse with fellow students of Late Antiquity around the world.

Babylonian Jewry, the Babylonian Talmud, and the Sasanian Empire

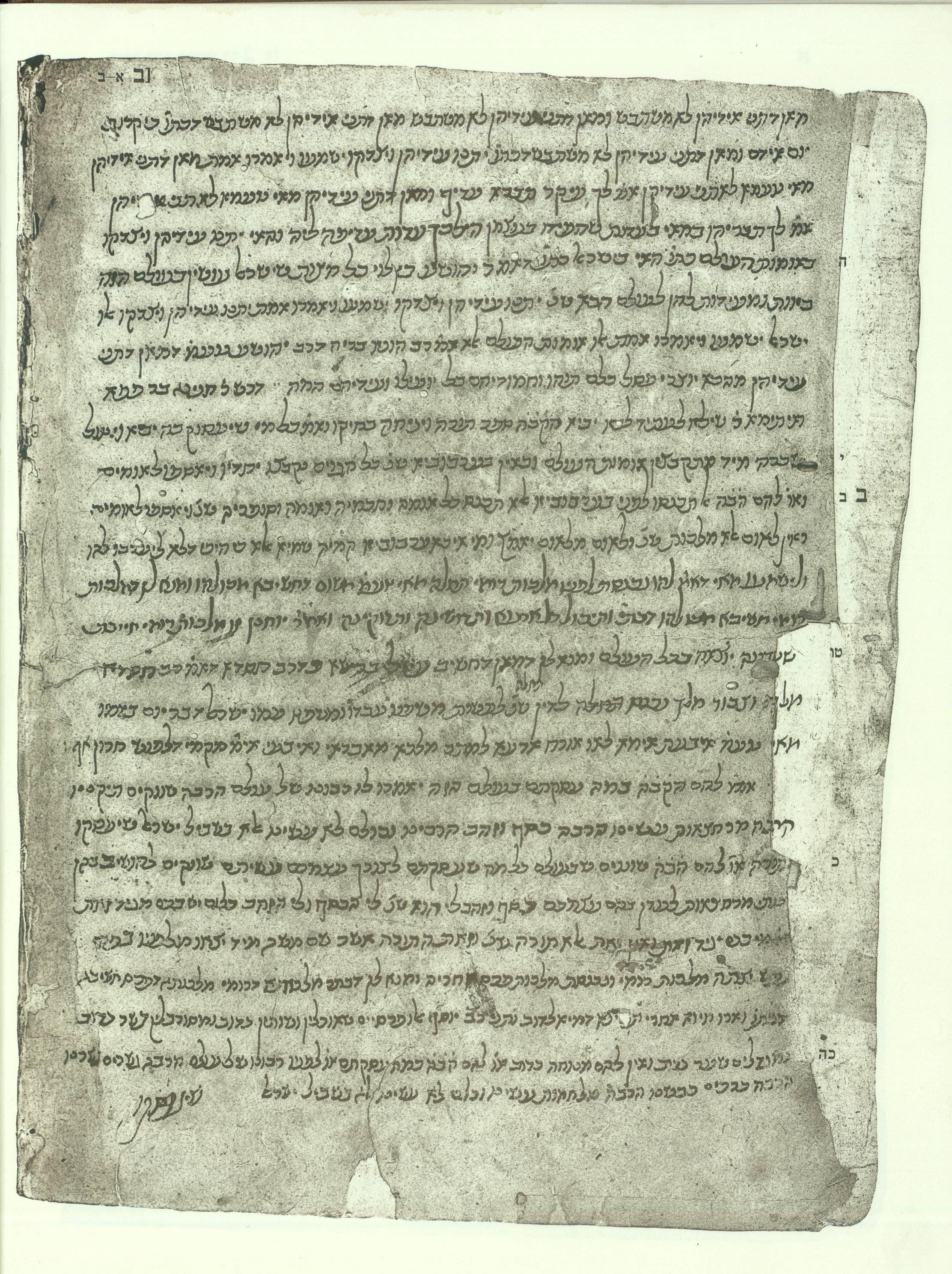

Turning to a particular corner of late antique Judaism—the Jews of Sasanian Babylonia—we face similar opportunities and challenges from the expansion of Late Antique Studies to include the Sasanian Empire. The opportunities again include pooling resources from Sasanian and Jewish Studies to produce better understandings of the two entities. Indeed, the study of Babylonian Jewry and their chief cultural artifact—the Babylonian Talmud—has previously been impoverished by a narrow, parochial focus on philology, with little awareness of the context in which the Talmud was compiled. Language instruction in Middle Persian geared towards Talmudists, and collaborations between Talmudists and Iranists, has finally begun to change this picture over the past decade. The burgeoning discipline of “Irano-Talmudica” has been one of the most exciting—if also controversial—developments in Jewish Studies in a long time.5

One distinct advantage here, though again one with potential risks, is the possibility of lining up the periodization of the Sasanian era—224/6–651 CE—with the “Talmudic Period,” beginning in third-century Babylonia with the period of the amoraim (as the rabbis during the third to fifth centuries are known), and concluding with the redaction of the Talmud by unnamed “editors,” probably sometime during the sixth century.6 It may be tempting to view the “Talmudic Period” as largely defined by the dynamics of the Sasanian Empire, and even posit that the production of the Talmud somehow resulted from the Sasanian context.7 This is an intriguing hypothesis, though one that is difficult to prove, and which will require hard thinking to unfurl its potential implications.

Another problem, which I believe is worth lingering on, is the way in which the expansion of Sasanian Studies to incorporate research into Babylonian Judaism can actually reify the binary distinction between two separate realms—the Sasanian and the Babylonian Jewish—while claiming that one entity is crucial for understanding the other. There is a tendency to measure how the central—that is, Sasanian—domain may have influenced the particularistic Babylonian Jewish one; specifically, how it left its own, Iranian, sphere and penetrated the Jewish (and thus non-Iranian?) one—and how Babylonian Jewry reacted to Sasanian power or culture.

Sasanianists are normally invested in the history of the Sasanian Empire and its imperial machinery, not in the dense, literally “talmudic” literature of an Aramaic-speaking minority dwelling in Mesopotamia. It is understandable that for the most part, interest in non-Iranian communities living in the empire would mainly involve gauging the reactions of Sasanian subjects to Sasanian actions and policies. From the opposite end, scholars of these non-Iranian communities who are attentive to the Sasanian context are typically looking for instances of direct Sasanian (or Zoroastrian) influence on religious life, or for evidence of Sasanian persecution or support. Trying to simultaneously take into account both vantage points can lead to a more robust account of the Sasanian Empire, or a richer story about a particular Sasanian community.8 Yet in all of this, the underlying distinction between center and periphery remains, and it exacts a price.

Rethinking center and periphery in Rabbinics

In considering this last point, I wish to explore in greater detail Babylonian Jewry and the Babylonian Talmud, which developed and thrived in a Sasanian Mesopotamian context while in contact with Palestinian Jewry and the Palestinian Talmud to the west, more specifically, in the Roman Galilee. This will help us better understand matters of center and periphery in terms of Sasanian Studies and Babylonian Jewry, and regarding Late Antiquity and Sasanian Studies as well.

First, some basic facts: Babylonian Jewry traces its roots to the early sixth century BCE, when the Judeans who were exiled from Judea arrived and settled in Mesopotamia, as described in the late books of the Hebrew Bible and now documented in a newly discovered cache of tablets from a locale in Mesopotamia referred to as “Al-Yahudu”—i.e., “Judea-town.”9 When the Achaemenids rose to power in the latter half of the sixth century BCE and demolished the Babylonian Empire, some Jews returned to Judea to resettle Jerusalem and rebuild its temple, while many stayed in the Babylonian Diaspora and even migrated further east, into Persia. When this Second Temple was destroyed about a half a millennium later during the Great Revolt against Rome in 70 CE, and when more destruction was wrought in the wake of the Second Jewish War in the 130s, some Jews again left for Babylonia.

By the time the Sasanians rose to power, there was a substantial community of Babylonian rabbis who, along with colleagues in the Galilee, transmitted, discussed, and advanced rabbinic law as it was laid out in the Mishnah—the definitive “halakhic” corpus compiled by the Jewish Patriarch in the Galilee in 200 CE. For the next two centuries, the two major rabbinic centers, in Roman Palestine and Sasanian Babylonia respectively, were closely linked as rabbinic scholars traveled up the Euphrates and down the Mediterranean coast and back, bringing the traditions and discussions of the Mishnah and parallel texts which comprise the material that makes up what is now called the Babylonian and Palestinian Talmuds.10

In many respects, the relationship between the two rabbinic centers could be understood as hierarchically structured along the lines of center and periphery. Thus, the land of Israel was the homeland while Babylonia was diaspora—in fact, the quintessential diaspora. This mytho-geographic distinction runs very deep in Jewish culture, and in scholarship on classical Judaism as well. Further, the relationship between the two talmudic corpora, Palestinian and Babylonian, is also, in a sense, hierarchically ordered with a clear center and periphery. According to this scheme, the Mishnah is the textual core whose structure and content organizes and defines the Babylonian Talmud, and scholars have demonstrated that many of the discussions in the Babylonian Talmud are based on earlier Palestinian discussions of the Mishnah. Reading the Babylonian Talmud against Palestinian parallels—as responsible talmudic philology demands—reinforces the impression that the Babylonian Talmud is an entirely commentarial, second-order form of literature, subordinate to the central Mishnah and its accompanying Palestinian rabbinic discussion.

When we dig deeper into the relationship between rabbinic Palestine and rabbinic Babylonia, however, we discover that center and periphery can trade places; at times, the distinction is effaced altogether. First, even Galilean rabbis saw themselves as “exiled” in the sense that the destruction of the Temple and Jerusalem exiled them from the cultic and spiritual geographic ideal of the Jewish people flourishing in a Jerusalem-centered homeland. Hence, both Galilean and Babylonian Jewry were dwelling in diasporas of a kind. Furthermore, as much as the Babylonian Talmud is a commentary on the Mishnah and is often based on Palestinian rabbinic discourse, it developed into an impressively unequaled—if not entirely sui generis—scholastic specimen. In terms of intra-Jewish politics, while Palestinian rabbis continued to assert political and spiritual supremacy over their Babylonian colleagues throughout the second, third, and fourth centuries, Babylonian rabbis became more and more confident of their power and fought back. Let us not forget that it was ultimately the Babylonian Talmud which came to define Jewish law and life from the Middle Ages until today—not the largely neglected Palestinian Talmud.11

It is also worth thinking about the role that geopolitical center/periphery dynamics played in Jewish and late antique history. Roman Galilee was, of course, a part of the Roman province Syria Palaestina from after the Second Jewish Revolt until 390, at which point it became Palaestina Secunda until the Arab Conquests. Babylonia, on the other hand, was located in close proximity to the economic and political heart of the Sasanian Empire—indeed, the “talmudic” town of Maḥoza, where the influential fourth-century rabbi, Rava, lived, was part of the Sasanian winter-capital metropolitan area.12 In this way, Babylonian Jewry flourished at a major center of Sasanian imperial power, while Galilean Jews lived in an area that was, in many respects, marginal to Roman and subsequently, Byzantine, imperial power.

In his A Traveling Homeland, Daniel Boyarin has recently argued that studying Babylonian rabbinic culture as merely influenced by, or reacting to, Palestinian rabbinic culture misses how this “doubled” rabbinic text and rabbinic culture actually functioned.13 According to Boyarin, reading Babylonian and Palestinian rabbinic Judaism in terms of center and periphery—in either direction—ignores a fundamental feature of rabbinic society, which resists a pat distinction between homeland and diaspora. Even if one’s primary research focus is on Babylonian Jewry, understanding this entity we call “Babylonian Jewry” requires paying attention to Palestinian Jewry, which is, of course, an integral part of its imaginary.

Some of the spatial matters affecting scholarship on late antique Babylonian and Palestinian Jewry are relevant for thinking about Sasanian Studies and Sasanian religious communities, as well as the relationship between Sasanian Studies and the study of Late Antiquity. In seeking to pursue a Sasanian research program, we must be fully aware of the dynamics of center/periphery as they play out in terms of contemporary academic politics, as well as in our objects of study. To what extent should we see ourselves as scholars of Late Antiquity, admittedly with a distinctly eastern tilt? How much are the paradigms of the academic “center” relevant for us? Is it necessary for Sasanianists to conceive of the Sasanian Empire as the center while Rome/Byzantium is displaced, or is this thinking already too binary? Likewise, how should scholars of “minority” Sasanian religious communities and literatures, like Jews and the Talmud, or Christians and Eastern Syriac literature, frame their work in relation to the Sasanian court, ethnic Persians, Zoroastrian priests, and Zoroastrian texts? It is exciting and gratifying to follow research that charts new and sophisticated pathways through this complex terrain, including the work of scholars like Maria Macuch,14 Richard Payne,15 and Simcha Gross.16

A final, concluding thought: Even if it may be best to view these political/religious entities formerly understood as central or peripheral to one another as actually interlocking, most of the shifts described in this paper took place within a broad, but circumscribed, geographical and temporal frame—that of Eastern Late Antiquity, or East LA for short. Whether we are thinking about Babylonian Jewry in relation to the Sasanians, Babylonian Jews vis-à-vis Palestinian Jews, or the Sasanians and their Roman neighbors to the west, Eastern Late Antiquity is the primary site of these dynamics. As we look ahead, it is this domain which should be the focus of our widened, more contextually sensitive lens.

About the author

Shai Secunda occupies the Jacob Neusner Chair in the History and Theology of Judaism at Bard College. He researches and teaches classical Judaism and Zoroastrianism and their late antique interrelations. His first book, The Iranian Talmud: Reading the Bavli Talmud in its Sasanian Context (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013) was recently released in paperback. In addition to academic publications, he regularly writes on Jewish scholarship and popular culture for the Jewish Review of Books.

Notes

- The session, convened by Michael Pregill, was held at the biannual meeting of the International Society of Iranian Studies and sponsored by ILEX Foundation. Khodadad Rezakhani was the session respondent. ↑

- For the inclusion of Eastern territories within the late antique paradigm, see the introduction to Teresa Bernheimer and Adam J. Silverstein (eds.), Late Antiquity: Eastern Perspectives (Cambridge: Gibb Memorial Trust, 2012), 1–12. For the inclusion of Islam, see Garth Fowden, Before and After Muḥammad: The First Millennium Refocused (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014). ↑

- This, at least, is how the project is described in the very first page of Peter Brown’s field-establishing The World of Late Antiquity: From Marcus Aurelius to Muhammad (London: Thames and Hudson, 1971): “It is only too easy to write about the Late Antique world as if it were merely a melancholy tale of ‘Decline and Fall’… On the other hand, we are increasingly aware of the astounding new beginnings associated with this period: we go to it to discover why Europe became Christian and why the Near East became Muslim.” Of course, there are a number of political and rhetorical reasons why Brown would want to frame the historiographical arch in this way. In a corrective spirit, Fowden, Before and After Muḥammad, 5–9, has questioned the extent to which Edward Gibbon, who famously authored The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (6 vols.; London: Strahan and Cadell, 1776–1789), held a non-dynamic, lachrymose view of said decline. ↑

- This is not to deny the significance of the alignment between the Sasanians and Zoroastrianism during this period, or for that matter the parallels between the Roman and Sasanian Empires, regarding which see Touraj Daryaee’s contribution to this volume. Rather, it is to acknowledge the many important differences between the Christianization of Rome and the status of Zoroastrianism in the Sasanian Empire, most glaringly, the dramatic reversal of fortunes of Christianity in the Roman Empire from persecuted to state religion, which has no Sasanian parallel. ↑

- For an introduction to this new undertaking, see Shai Secunda, The Iranian Talmud: Reading the Bavli in Its Sasanian Context (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014). Note, however, that the study of the Talmud in its Iranian context has been developing rather quickly, so that my treatment there is already somewhat out of date, particularly due to the further integration of Syriac Studies into the field. See Simcha Gross, “Irano-Talmudica and Beyond: Next Steps in the Contextualization of the Babylonian Talmud,” Jewish Quarterly Review 106 (2016): 248–255. ↑

- Debates concerning the “sealing” of the Talmud and the role of anonymous editors have accompanied the academic study of the Talmud for many decades. The most indispensable treatment can still be found in H. L. Strack and Günter Stemberger, Introduction to the Talmud and Midrash, trans. Markus Bockmuehl (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1991). A sixth-century Sasanian context for the work of the anonymous talmudic editors has recently been advanced by Simcha Gross and other scholars as part of a Hebrew University workshop “A Sasanian Renaissance: Reevaluating the Sixth Century between Empire and Minorities,” held June 13–14, 2018. ↑

- On a related point, I am currently researching how the production and organization of massive texts in the Sasanian Empire, particularly that of the Zoroastrian dēn (sacred tradition), may help us understand the emergence of the Babylonian Talmud as the sole, though all-encompassing, compilation produced by Babylonian rabbinic Jewry. ↑

- For a good example of scholarship in which Sasanianists consult the Talmud in the course of regular research, see Khodadad Rezakhani and Michael G. Morony, “Markets for Land, Labour and Capital in Late Antique Iraq, AD 200–700,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 57 (2014): 231–261. ↑

- See Ran Zadok, The Earliest Diaspora: Israelites and Judeans in Pre-Hellenistic Mesopotamia (Tel Aviv: Diaspora Research Institute, 2002). On the significance of the recent finds from Al-Yahudu, which still have not been fully published, see Kathleen Abraham, “The Reconstruction of Jewish Communities in the Persian Empire: The Al-Yahudu Clay Tablets,” in David Yeroushalmi (ed.), Light and Shadows: The Story of Iranian Jews (Los Angeles: Fowler Museum at UCLA, 2012), 264–268. ↑

- For a convenient and brief history of Babylonian Jewry during Late Antiquity, see Isaiah Gafni, “The Political, Social, and Economic History of Babylonian Jewry, c. 224–638 CE,” in Steven Katz (ed.), The Cambridge History of Judaism, Volume 4: The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 792–820. ↑

- For further insight into this process, which occurred during the geonic period, see Robert Brody, The Geonim of Babylonia and the Shaping of Medieval Jewish Culture (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998). ↑

- On Babylonian Jewish geography, including a lengthy discussion of Maḥoza, see Aharon Oppenheimer, Babylonia Judaica in the Talmudic Period (Beihefte zum Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients B, Geisteswissenschaften 47; Wiesbaden: Reichert, 1983). ↑

- Daniel Boyarin, A Traveling Homeland: The Babylonian Talmud as Diaspora (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015). ↑

- See for example Maria Macuch, “Jewish Jurisdiction within the Framework of the Sasanian Legal System,” in Uri Gabbay and Shai Secunda (eds.), Encounters by the Rivers of Babylon: Scholarly Conversations between Jews, Iranians, and Babylonians in Antiquity (Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism 160; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2014), 147–160. ↑

- Richard E. Payne, A State of Mixture: Christians, Zoroastrians, and Iranian Political Culture in Late Antiquity (Transformation of the Classical Heritage 56; Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2015). ↑

- Simcha Gross, “Empire and Neighbors: Babylonian Jewish Identity in Its Local and Imperial Context” (Ph.D. diss, Yale University, 2017). ↑

East LA: Center and Periphery in the Study of Late Antiquity and the New Irano-Talmudica

Introduction: expanding LA, expanding Sasanian Studies

This short essay grew out of a conference session that considered new perspectives on late antique Iran and Iraq.1 My contribution to this topic is entirely theoretical—which is to say I stay my philological hand—as I explore issues of center and periphery relating to geopolitical and religious facts on the ground during Late Antiquity, as well as the disciplinary terrain governing the study of Sasanian Iran. These thoughts are inspired by recent work that redraws the spatial and chronological limes of Late Antiquity, thereby bringing other religions and civilizations into the picture, particularly Islam.2 Here, I think through three overlapping interrelations—namely, Babylonian Jewry and the Sasanians, Babylonian and Palestinian rabbis, and the Sasanian and Roman Empires—and consider lessons learned from evaluating one set of dynamics alongside the others.

The effort to include Sasanian Studies within the purview of Late Antiquity can be compared with the expansion of Sasanian Studies to incorporate non-Iranian communities living in the empire, such as Babylonian Jewry. In both instances, scholarly interest has widened to include societies previously thought irrelevant to their areas of research, yet now recognized as significant factors, despite apparent spatial, chronological, linguistic, religious, and cultural differences. Such a reorientation comes with obvious benefits, and with some less obvious costs.

At its core, the growth of the study of Late Antiquity over the past half-century has itself been powered by a desire to correct a long-standing negative attitude towards this epoch, which had previously been seen as a time of decline and darkness.3 The establishment of Late Antiquity as an historical period worthy of study was crucial first and foremost for revisiting the history of the West, and particularly for better understanding how the Western world got from the classical age through the Middle Ages, and ultimately to the way we live now. It is just as important to consider the political and intellectual forces now expanding the chronological limes of Late Antiquity later, to include, say, early Islam, and its geographical borders eastward, to include Byzantium’s ever-present “other”—the Sasanian Empire. What do Late Antique Studies and Sasanian Studies have to gain here, and what do they have to lose?

The benefits for Sasanianists are clear. The study of Late Antiquity is flourishing, so tapping into this enthusiasm requires little justification. On more substantive grounds, there is a strong case to be made that the history of the Sasanian Empire is an integral part of the history of the Roman and Byzantine Empires. After all, the Sasanians saw themselves and their territories as interlinked with the Eastern Mediterranean.

At the same time, applying a late antique periodization initially driven by a particular set of factors to the Sasanian Empire can be disorienting and misleading. Parallels to key features of Late Antiquity in the West—such as Constantine’s adoption of Christianity—are either not present at all, or are at least less distinct, in Eastern Late Antiquity. Assuming that the Sasanian entanglement with Zoroastrianism is equivalent to the Christianization of Rome, or stating that Zoroastrianism had become the “state religion” of the Sasanians a la Christianity and the Roman Empire, might count as a “cost” of over-reading Sasanian history through the lens of Late Antiquity.4

“Late Antiquity,” Jewish Studies, and Israeli higher education

The phenomenon of Jewish Studies scholars reframing their work in terms of “Late Antiquity” is likewise worth pondering. For example: for some time, scholars in Jewish Studies have considered discarding the parochial term “the talmudic period” as a designation for the history of the Jews from the third to the seventh centuries CE, in favor of adopting the term “Late Antiquity” instead. Beyond mere semantics, what is lost and gained in this terminological shift?

As an illustration, a recent graduate program in late antiquity at the Hebrew University has struggled to define what “Late Antiquity” should mean in an academic context that, for obvious reasons, is far stronger in talmudic philology than, e.g., the study of Augustine. As with the example of Sasanian Studies, the question is again whether and how to adopt a periodization that was originally about the transition of the Greco-Roman classical world into the Middle Ages—where Jews and their history play, at most, a supporting role—to an academic context in which the story of the Jews is far less marginal. At times, the adoption of the paradigm of Late Antiquity in Jewish Studies and in Israeli higher education has been, more or less, seamless. In other instances, it has led to misrepresentations—in both directions. Thus, “Late Antiquity” has been uncritically presented as a self-evidently relevant periodization for Jewish Studies, while students in Israeli programs in Late Antiquity are perhaps insufficiently immersed in the “classical” sources and paradigms of Late Antiquity (at least as conventionally defined) to be able to intelligently converse with fellow students of Late Antiquity around the world.

Babylonian Jewry, the Babylonian Talmud, and the Sasanian Empire

Turning to a particular corner of late antique Judaism—the Jews of Sasanian Babylonia—we face similar opportunities and challenges from the expansion of Late Antique Studies to include the Sasanian Empire. The opportunities again include pooling resources from Sasanian and Jewish Studies to produce better understandings of the two entities. Indeed, the study of Babylonian Jewry and their chief cultural artifact—the Babylonian Talmud—has previously been impoverished by a narrow, parochial focus on philology, with little awareness of the context in which the Talmud was compiled. Language instruction in Middle Persian geared towards Talmudists, and collaborations between Talmudists and Iranists, has finally begun to change this picture over the past decade. The burgeoning discipline of “Irano-Talmudica” has been one of the most exciting—if also controversial—developments in Jewish Studies in a long time.5

One distinct advantage here, though again one with potential risks, is the possibility of lining up the periodization of the Sasanian era—224/6–651 CE—with the “Talmudic Period,” beginning in third-century Babylonia with the period of the amoraim (as the rabbis during the third to fifth centuries are known), and concluding with the redaction of the Talmud by unnamed “editors,” probably sometime during the sixth century.6 It may be tempting to view the “Talmudic Period” as largely defined by the dynamics of the Sasanian Empire, and even posit that the production of the Talmud somehow resulted from the Sasanian context.7 This is an intriguing hypothesis, though one that is difficult to prove, and which will require hard thinking to unfurl its potential implications.

Another problem, which I believe is worth lingering on, is the way in which the expansion of Sasanian Studies to incorporate research into Babylonian Judaism can actually reify the binary distinction between two separate realms—the Sasanian and the Babylonian Jewish—while claiming that one entity is crucial for understanding the other. There is a tendency to measure how the central—that is, Sasanian—domain may have influenced the particularistic Babylonian Jewish one; specifically, how it left its own, Iranian, sphere and penetrated the Jewish (and thus non-Iranian?) one—and how Babylonian Jewry reacted to Sasanian power or culture.

Sasanianists are normally invested in the history of the Sasanian Empire and its imperial machinery, not in the dense, literally “talmudic” literature of an Aramaic-speaking minority dwelling in Mesopotamia. It is understandable that for the most part, interest in non-Iranian communities living in the empire would mainly involve gauging the reactions of Sasanian subjects to Sasanian actions and policies. From the opposite end, scholars of these non-Iranian communities who are attentive to the Sasanian context are typically looking for instances of direct Sasanian (or Zoroastrian) influence on religious life, or for evidence of Sasanian persecution or support. Trying to simultaneously take into account both vantage points can lead to a more robust account of the Sasanian Empire, or a richer story about a particular Sasanian community.8 Yet in all of this, the underlying distinction between center and periphery remains, and it exacts a price.

Rethinking center and periphery in Rabbinics

In considering this last point, I wish to explore in greater detail Babylonian Jewry and the Babylonian Talmud, which developed and thrived in a Sasanian Mesopotamian context while in contact with Palestinian Jewry and the Palestinian Talmud to the west, more specifically, in the Roman Galilee. This will help us better understand matters of center and periphery in terms of Sasanian Studies and Babylonian Jewry, and regarding Late Antiquity and Sasanian Studies as well.

First, some basic facts: Babylonian Jewry traces its roots to the early sixth century BCE, when the Judeans who were exiled from Judea arrived and settled in Mesopotamia, as described in the late books of the Hebrew Bible and now documented in a newly discovered cache of tablets from a locale in Mesopotamia referred to as “Al-Yahudu”—i.e., “Judea-town.”9 When the Achaemenids rose to power in the latter half of the sixth century BCE and demolished the Babylonian Empire, some Jews returned to Judea to resettle Jerusalem and rebuild its temple, while many stayed in the Babylonian Diaspora and even migrated further east, into Persia. When this Second Temple was destroyed about a half a millennium later during the Great Revolt against Rome in 70 CE, and when more destruction was wrought in the wake of the Second Jewish War in the 130s, some Jews again left for Babylonia.

By the time the Sasanians rose to power, there was a substantial community of Babylonian rabbis who, along with colleagues in the Galilee, transmitted, discussed, and advanced rabbinic law as it was laid out in the Mishnah—the definitive “halakhic” corpus compiled by the Jewish Patriarch in the Galilee in 200 CE. For the next two centuries, the two major rabbinic centers, in Roman Palestine and Sasanian Babylonia respectively, were closely linked as rabbinic scholars traveled up the Euphrates and down the Mediterranean coast and back, bringing the traditions and discussions of the Mishnah and parallel texts which comprise the material that makes up what is now called the Babylonian and Palestinian Talmuds.10

In many respects, the relationship between the two rabbinic centers could be understood as hierarchically structured along the lines of center and periphery. Thus, the land of Israel was the homeland while Babylonia was diaspora—in fact, the quintessential diaspora. This mytho-geographic distinction runs very deep in Jewish culture, and in scholarship on classical Judaism as well. Further, the relationship between the two talmudic corpora, Palestinian and Babylonian, is also, in a sense, hierarchically ordered with a clear center and periphery. According to this scheme, the Mishnah is the textual core whose structure and content organizes and defines the Babylonian Talmud, and scholars have demonstrated that many of the discussions in the Babylonian Talmud are based on earlier Palestinian discussions of the Mishnah. Reading the Babylonian Talmud against Palestinian parallels—as responsible talmudic philology demands—reinforces the impression that the Babylonian Talmud is an entirely commentarial, second-order form of literature, subordinate to the central Mishnah and its accompanying Palestinian rabbinic discussion.

When we dig deeper into the relationship between rabbinic Palestine and rabbinic Babylonia, however, we discover that center and periphery can trade places; at times, the distinction is effaced altogether. First, even Galilean rabbis saw themselves as “exiled” in the sense that the destruction of the Temple and Jerusalem exiled them from the cultic and spiritual geographic ideal of the Jewish people flourishing in a Jerusalem-centered homeland. Hence, both Galilean and Babylonian Jewry were dwelling in diasporas of a kind. Furthermore, as much as the Babylonian Talmud is a commentary on the Mishnah and is often based on Palestinian rabbinic discourse, it developed into an impressively unequaled—if not entirely sui generis—scholastic specimen. In terms of intra-Jewish politics, while Palestinian rabbis continued to assert political and spiritual supremacy over their Babylonian colleagues throughout the second, third, and fourth centuries, Babylonian rabbis became more and more confident of their power and fought back. Let us not forget that it was ultimately the Babylonian Talmud which came to define Jewish law and life from the Middle Ages until today—not the largely neglected Palestinian Talmud.11

It is also worth thinking about the role that geopolitical center/periphery dynamics played in Jewish and late antique history. Roman Galilee was, of course, a part of the Roman province Syria Palaestina from after the Second Jewish Revolt until 390, at which point it became Palaestina Secunda until the Arab Conquests. Babylonia, on the other hand, was located in close proximity to the economic and political heart of the Sasanian Empire—indeed, the “talmudic” town of Maḥoza, where the influential fourth-century rabbi, Rava, lived, was part of the Sasanian winter-capital metropolitan area.12 In this way, Babylonian Jewry flourished at a major center of Sasanian imperial power, while Galilean Jews lived in an area that was, in many respects, marginal to Roman and subsequently, Byzantine, imperial power.

In his A Traveling Homeland, Daniel Boyarin has recently argued that studying Babylonian rabbinic culture as merely influenced by, or reacting to, Palestinian rabbinic culture misses how this “doubled” rabbinic text and rabbinic culture actually functioned.13 According to Boyarin, reading Babylonian and Palestinian rabbinic Judaism in terms of center and periphery—in either direction—ignores a fundamental feature of rabbinic society, which resists a pat distinction between homeland and diaspora. Even if one’s primary research focus is on Babylonian Jewry, understanding this entity we call “Babylonian Jewry” requires paying attention to Palestinian Jewry, which is, of course, an integral part of its imaginary.

Some of the spatial matters affecting scholarship on late antique Babylonian and Palestinian Jewry are relevant for thinking about Sasanian Studies and Sasanian religious communities, as well as the relationship between Sasanian Studies and the study of Late Antiquity. In seeking to pursue a Sasanian research program, we must be fully aware of the dynamics of center/periphery as they play out in terms of contemporary academic politics, as well as in our objects of study. To what extent should we see ourselves as scholars of Late Antiquity, admittedly with a distinctly eastern tilt? How much are the paradigms of the academic “center” relevant for us? Is it necessary for Sasanianists to conceive of the Sasanian Empire as the center while Rome/Byzantium is displaced, or is this thinking already too binary? Likewise, how should scholars of “minority” Sasanian religious communities and literatures, like Jews and the Talmud, or Christians and Eastern Syriac literature, frame their work in relation to the Sasanian court, ethnic Persians, Zoroastrian priests, and Zoroastrian texts? It is exciting and gratifying to follow research that charts new and sophisticated pathways through this complex terrain, including the work of scholars like Maria Macuch,14 Richard Payne,15 and Simcha Gross.16

A final, concluding thought: Even if it may be best to view these political/religious entities formerly understood as central or peripheral to one another as actually interlocking, most of the shifts described in this paper took place within a broad, but circumscribed, geographical and temporal frame—that of Eastern Late Antiquity, or East LA for short. Whether we are thinking about Babylonian Jewry in relation to the Sasanians, Babylonian Jews vis-à-vis Palestinian Jews, or the Sasanians and their Roman neighbors to the west, Eastern Late Antiquity is the primary site of these dynamics. As we look ahead, it is this domain which should be the focus of our widened, more contextually sensitive lens.

About the author

Shai Secunda occupies the Jacob Neusner Chair in the History and Theology of Judaism at Bard College. He researches and teaches classical Judaism and Zoroastrianism and their late antique interrelations. His first book, The Iranian Talmud: Reading the Bavli Talmud in its Sasanian Context (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013) was recently released in paperback. In addition to academic publications, he regularly writes on Jewish scholarship and popular culture for the Jewish Review of Books.

Notes

- The session, convened by Michael Pregill, was held at the biannual meeting of the International Society of Iranian Studies and sponsored by ILEX Foundation. Khodadad Rezakhani was the session respondent. ↑

- For the inclusion of Eastern territories within the late antique paradigm, see the introduction to Teresa Bernheimer and Adam J. Silverstein (eds.), Late Antiquity: Eastern Perspectives (Cambridge: Gibb Memorial Trust, 2012), 1–12. For the inclusion of Islam, see Garth Fowden, Before and After Muḥammad: The First Millennium Refocused (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014). ↑

- This, at least, is how the project is described in the very first page of Peter Brown’s field-establishing The World of Late Antiquity: From Marcus Aurelius to Muhammad (London: Thames and Hudson, 1971): “It is only too easy to write about the Late Antique world as if it were merely a melancholy tale of ‘Decline and Fall’… On the other hand, we are increasingly aware of the astounding new beginnings associated with this period: we go to it to discover why Europe became Christian and why the Near East became Muslim.” Of course, there are a number of political and rhetorical reasons why Brown would want to frame the historiographical arch in this way. In a corrective spirit, Fowden, Before and After Muḥammad, 5–9, has questioned the extent to which Edward Gibbon, who famously authored The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (6 vols.; London: Strahan and Cadell, 1776–1789), held a non-dynamic, lachrymose view of said decline. ↑

- This is not to deny the significance of the alignment between the Sasanians and Zoroastrianism during this period, or for that matter the parallels between the Roman and Sasanian Empires, regarding which see Touraj Daryaee’s contribution to this volume. Rather, it is to acknowledge the many important differences between the Christianization of Rome and the status of Zoroastrianism in the Sasanian Empire, most glaringly, the dramatic reversal of fortunes of Christianity in the Roman Empire from persecuted to state religion, which has no Sasanian parallel. ↑

- For an introduction to this new undertaking, see Shai Secunda, The Iranian Talmud: Reading the Bavli in Its Sasanian Context (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014). Note, however, that the study of the Talmud in its Iranian context has been developing rather quickly, so that my treatment there is already somewhat out of date, particularly due to the further integration of Syriac Studies into the field. See Simcha Gross, “Irano-Talmudica and Beyond: Next Steps in the Contextualization of the Babylonian Talmud,” Jewish Quarterly Review 106 (2016): 248–255. ↑

- Debates concerning the “sealing” of the Talmud and the role of anonymous editors have accompanied the academic study of the Talmud for many decades. The most indispensable treatment can still be found in H. L. Strack and Günter Stemberger, Introduction to the Talmud and Midrash, trans. Markus Bockmuehl (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1991). A sixth-century Sasanian context for the work of the anonymous talmudic editors has recently been advanced by Simcha Gross and other scholars as part of a Hebrew University workshop “A Sasanian Renaissance: Reevaluating the Sixth Century between Empire and Minorities,” held June 13–14, 2018. ↑

- On a related point, I am currently researching how the production and organization of massive texts in the Sasanian Empire, particularly that of the Zoroastrian dēn (sacred tradition), may help us understand the emergence of the Babylonian Talmud as the sole, though all-encompassing, compilation produced by Babylonian rabbinic Jewry. ↑

- For a good example of scholarship in which Sasanianists consult the Talmud in the course of regular research, see Khodadad Rezakhani and Michael G. Morony, “Markets for Land, Labour and Capital in Late Antique Iraq, AD 200–700,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 57 (2014): 231–261. ↑

- See Ran Zadok, The Earliest Diaspora: Israelites and Judeans in Pre-Hellenistic Mesopotamia (Tel Aviv: Diaspora Research Institute, 2002). On the significance of the recent finds from Al-Yahudu, which still have not been fully published, see Kathleen Abraham, “The Reconstruction of Jewish Communities in the Persian Empire: The Al-Yahudu Clay Tablets,” in David Yeroushalmi (ed.), Light and Shadows: The Story of Iranian Jews (Los Angeles: Fowler Museum at UCLA, 2012), 264–268. ↑

- For a convenient and brief history of Babylonian Jewry during Late Antiquity, see Isaiah Gafni, “The Political, Social, and Economic History of Babylonian Jewry, c. 224–638 CE,” in Steven Katz (ed.), The Cambridge History of Judaism, Volume 4: The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 792–820. ↑

- For further insight into this process, which occurred during the geonic period, see Robert Brody, The Geonim of Babylonia and the Shaping of Medieval Jewish Culture (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998). ↑

- On Babylonian Jewish geography, including a lengthy discussion of Maḥoza, see Aharon Oppenheimer, Babylonia Judaica in the Talmudic Period (Beihefte zum Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients B, Geisteswissenschaften 47; Wiesbaden: Reichert, 1983). ↑

- Daniel Boyarin, A Traveling Homeland: The Babylonian Talmud as Diaspora (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015). ↑

- See for example Maria Macuch, “Jewish Jurisdiction within the Framework of the Sasanian Legal System,” in Uri Gabbay and Shai Secunda (eds.), Encounters by the Rivers of Babylon: Scholarly Conversations between Jews, Iranians, and Babylonians in Antiquity (Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism 160; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2014), 147–160. ↑

- Richard E. Payne, A State of Mixture: Christians, Zoroastrians, and Iranian Political Culture in Late Antiquity (Transformation of the Classical Heritage 56; Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2015). ↑

- Simcha Gross, “Empire and Neighbors: Babylonian Jewish Identity in Its Local and Imperial Context” (Ph.D. diss, Yale University, 2017). ↑