PDF

Download

Citations

Click and drag then release to select a passage to cite.

Annotations

How to submit annotations to Mizan Journal articles:

your work is published.

Search within

Thus Spoke the Ant

A Tale of Solomon between Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ and Jewish Aggadah

Thus Spoke the Ant

A Tale of Solomon between Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ and Jewish Aggadah

Introduction

Muslims, Christians, and Jews in the pre-modern Islamicate world all participated in the creation of a shared narrative culture. The stories they told often transcended religious and communal boundaries. This is true of the fables discussed by the other panel members, and it is also true of legends about the Biblical patriarchs, prophets,kings, and other heroes of the past. But—as the question posed in the description of this panel asks—

“Do traveling characters, tropes and allegories shape-shift to reflect their immediate historical context, or do they carry multiple origins and layers of cultural exchange that defy spatial and temporal boundaries?”

Similar or identical stories may mean different things to different readers, both individual readers and entire audiences. The question I would like to pose here is rather simple: how do different narrating communities adapt the same narrative materials used by their neighbors to fit the needs and expectations of their own members? In what ways do “rival tellings of shared stories” (to paraphrase Robert Gregg’s book title) diverge from one another? And more specifically, how does a shared “cultural hero”—in this case King Solomon—is made to mean different things?

I will examine these questions by looking into some subtle and not so subtle changes between the variants of a single legend that was shared among Muslims, Christians and Jews. I shall focus on two main adaptation strategies:

- Narrative additions and omissions;

- Shifting intertextualities;

The Legend of Solomon and the Haunted Castle: Background.

In short, the legend I am dealing with tells of Solomon’s travels on his flying carpet and his encounters with several unlikely peers, each of whom teaches the king a lesson in humility. During his journey, he has an altercation with the wind, who rebukes him for his boastfulness (in some versions); he converses with the queen of the ants, who puts him to shame for his haughtiness; and he roams the haunted corridors of a magnificent castle, wondering about the fate of its erstwhile dwellers and the identity of the mighty ruler that had built it. The builder finally turns out to be an ancient and long forgotten king called ʿĀd ibn Shaddād (or in some versions Shaddād ibn ʿĀd).

There are several manuscript versions of the legend copied by Muslim copyists (to the best of my knowledge, all of them remain unedited). For the purpose of this paper, I will be relying on a manuscript version that I located in the collections of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, in an eighteenth century manuscript of a work of the Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ genre.

Versions of the tale copied by Christian scribes include an early version in Garshūnī (unavailable to me as of yet), and a version copied by an Arab-Christian scribe in the 17th century. This version was edited by Nabil Watad in his 2009 M.A. thesis (and I rely on his unpublished edition). This version further shows affinities to a version of the tale published by Louis Cheikho in al-Machriq in 1921, based on an eighteenth-century manuscript and to some other manuscript versions (which may have also been copied by Christian scribes, though this cannot be ascertained). To the best of my knowledge, Cheikho’s edition is the only Arabic version of the tale available in print. However, it went entirely unnoticed by scholars.

Finally, Jewish versions of the tale include both texts in Judeo-Arabic and a pre-modern Hebrew translation, titled Maʿaśeh ha-nemalah (“Tale of the Ant”). The Hebrew version was first published by Adolf (Aharon) Jellinek in 1873, in his collection of short midrashim, titled Beit ha-Midrasch. The dating of the Hebrew version is hard to determine, but it was probably copied no earlier than the 18th century. I should note that the Hebrew version is undoubtedly a translation from Arabic. This is evident from the linguistic character of the Hebrew text, from its use of Arabic nomenclature, and from some obvious calques.

Additions and Omissions: The Two Variants

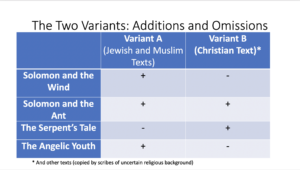

So, what are the differences between the versions? And whar can they tell us about their creators and their audiences? The most conspicuous difference is the inclusion or omission of certain episodes in various versions. These inclusions and omissions are so consistent, that they allow us to divide the extent versions of the tale into two main variants.

Variant A, which includes the Muslim and the Jewish (Hebrew) version, begins with the episode of Solomon’s rebuke by the Wind. While flying on his fabulous carpet surrounded by his human and non-human hosts, Solomon boasts of his supreme reign, the likes of which have never been given to anyone. A sudden gush of wind throws several thousand men off the king’s carpet. The enraged Solomon flogs the carpet and orders the wind to settle down. The wind then rebukes him for his boastfulness, and the king lowers his head, ashamed. This episode of Solomon’s altercation with the wind is entirely absent from Variant B, which is represented by the christian text. The middle episode of the story—Solomon’s conversation with the ant, is almost identical in both versions (and I shall return to it later).

It is in the last part of the tale that the most meaningful divergence between the two variants occurs. In both, Solomon arrives at a magnificent castle built of gold and silver. While roaming its corridors and reading inscriptions that bemoan the fate of its inhabitants, Solomon wonders who could have built it. Variant B provides the answer to the king’s bewilderment through a story told to him by a supernatural inhabitant of the castle: a gigantic serpent-demoness. The demoness tells the king that the castle was built by an ancient king called ʿĀd ibn Shaddād and that he and all who followed in his footsteps died because of their wickedness, and ever since, the castle has been haunted by demons. Solomon then proceeds to vanquish the demons and clear the castle from the evil that infested it.

The demoness and her story are entirely absent in Variant A. Here, the answer to the mystery of the castle’s origins comes at the very end of the tale. After vanquishing the demons, Solomon finds a golden inscription hanging from the neck of a statue. However, he cannot decipher it. Suddenly, a mysterious young man appears “from the desert”. The young man tells Solomon that God sent him to relieve the king from his stress. He deciphers the inscription for him; it reveals the name of the castle’s original owner, ʿĀd ibn Shaddād (in the Hebrew version: Shaddād ibn ʿĀd), and admonishes the reader to renounce this world and its wiles.

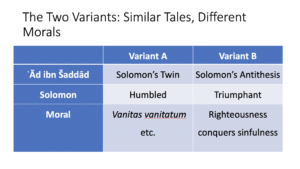

A comparison of the two variants shows that each leads to a different interpretation of the image of Solomon and of the tale as a whole. With its solemn coda, Variant A ends as a tale of moral humility. In it, Solomon learns several moral lessons through his encounters with his counterparts: through his clash with the wind, he learns that he is not above the forces of nature; through his dialogue with the ant, he learns that he is no better than even the tiniest of God’s creatures; and through his encounter with the castle and its mysterious builder, he learns that he does not surpass those who came before him, that he is a mere mortal, and that his knowledge and wisdom, though vast, are limited. Thus, Variant A shapes the legend as a moral tale, whose sober lesson can be summed up in the words of Ecclesiastes: Vanitas vanitatum, omnia vanitas.

Meanwhile, in presenting the tale of the castle and its ancient dwellers as one of idolatry, wickedness, and transgression, Variant B sets up an inverse mirror before Solomon. The ancient idolatrous occupants of the castle are here interpreted as the moral opposites of the righteous king. Indeed, in both versions Solomon clears the castle from idolatry and frees it from the demons that infest it, but only in Variant B can these actions be interpreted as Solomon’s triumph over the past. It leads to an understanding of the tale as a story about the triumph of righteousness over sinfulness.

Shifting Intertextualities

There are other, more subtle differences between the two versions. Before I move on to examine one of them, I should address the question of the story’s origins. It seems most likely that the story took shape within a Muslim milieu. The main evidence for this are the tale’s multiple Qurʾānic references: first and foremost Solomon’s encounter with the ant (to which I shall return shortly), but also the fact that the story mentions Solomon’s dominion over the wind, the Jinn and the animals, as mentioned in several places in the Qurʾān. According to some versions, the name of the wind that would carry Solomon’s carpet was rūḫāʾ, a Qurʾānic term mentioned in Q. 38, v. 36. In fact, the affinity between the tale and the Qurʾānic portrayal of Sulaymān is so obvious that the tale can be considered as a narrative expansion of the terse Qurʾānic references to Solomon, or in other words, as belonging to the Islamic genre of Qiṣaṣ al-Anbiyāʾ or “tales of the prophets”.

As I mentioned earlier, the most striking Qurʾānic reference is in the second part of the tale. In this part, Solomon arrives at the Valley of the Ants (Wādi ‘l-naml). There he hears one of the ants warning its mates: “Ants, enter your dwelling-places, lest Solomon and his hosts crush you!” This description is based entirely on Q. 27, v. 17–18, which recounts the arrival of Solomon and his troops to the valley of the Ants (wādi ‘l-naml) and Solomon’s conversation with the ant. And indeed, it is hardly surprising to find that the muslim version quotes the Qurʾān verbatim at this point, after which it tells of Solomon’s and the Ant’s conversation, and how the ant (like the wind before it) rebuked Solomon for his haughtiness.

When looking at the christian version of the tale, it is rather striking that the Qurʾānic text is replaced with a paraphrase. This seems a deliberate attempt on the part of the christian storyteller or copyist to conceal the Qurʾānic subtext of the tale. Now, the Hebrew version of the tale includes an almost literal translation of the Qurʾānic verse. However, as the Qurʾān was unfamiliar to most pre-modern (and sadly also to modern) Hebrew readers, the Qurʾānic reference would have posed no real religious problem or threat to the translator, the copyist, or the intended readership.

Moreover, Jewish and Christian audiences could just as easily interpret Solomon’s encounter with the ant as a reference not to the Qurʾān, but to the Bible, and quite easily so. After all, ants are mentioned twice in the Book of Proverbs, a work traditionally attributed to none other than King Solomon himself. The story of Solomon’s encounter with the ant (and the ant’s moral reproof of Solomon for his boastfulness) would then be perceived as a narrative expansion—a midrash—of Prov. 6, 6, in which the wisest of all men instructs: “Go to the ant, thou sluggard; consider her ways and be wise”, and perhaps also of Proverbs 30, 25, which mentions the ants’ resourcefulness.

The biblical overtones of the tale are further accentuated in the coda of the Hebrew version, which has the inscription of the ancient builder say: ”For everyone is destined to die, and nothing shall remain at one’s hands save for [one’s] good name” — A line that reverberates the words of Ecclesiastes—again, a work traditionally attributed to Solomon: “A good name is better than precious ointment; and the day of death than the day of one’s birth”. This is also in line with Variant A’s moral message, which again can be summed up with the words of Ecclesiastes: Vanitas vanitatum, omnia vanitas.

Conclusion

The legend of Solomon, which had probably originated among Muslim storytellers around the middle of the second millennium CE, spread beyond Muslim audiences and was adopted by Jews and Christians. This legend, and others like it, was especially suited to be adapted by followers of all Abrahamic religions, not only because its hero appeared in the canonical texts of all of them, but moreover, because the adjustments required to pass it as a “jewish” or a “christian” tale were rather minor: these adjustments mainly meant replacing Qurʾānic references with parallel Biblical ones, and that, as I have shown, was easily achieved. Thus, the story could be read as a piece of Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, a midrash Aggadah, or simply a christian legend.

To return to the question posed at the beginning of this lecture:

“Do traveling characters, tropes and allegories shape-shift to reflect their immediate historical context, or do they carry multiple origins and layers of cultural exchange that defy spatial and temporal boundaries?”

The Answer is of course: both. There are constants in the image of King Solomon (and other cultural heroes like him) that do not change, such as his wisdom, his rule over human and non-human subjects, his ability to bind demons, etc. These are parts of Solomon’s literary iconography as explored time and again in modern scholarship. Though these attributes are indeed integral, almost organic parts of the literary portrayals of Solomon, their meaning or significance are open to interpretation and re-fashioning. Like other mythical or legendary heroes, Solomon’s stories can always be retold and his image can always be created afresh, to suit the needs of the time, place, and audience.

The two variants that I have examined reveal a double image of Solomon, one that is familiar from other sources and other legends as well: on the one hand a boastful king who learns a lesson in humility, and on the other, a powerful mage who triumphs over evil.

But here is where things get a bit sticky: do these conflicting images of Solomon necessarily reflect the attitudes of different communities or different audiences? For now, it is not entirely clear whether the “serpent episode” was part of the “original” (and not necessarily christian) version or an addition of a later storyteller. This leads to another open question: Can we or should we judge the “originality” of the tale? After all, this tale was born out of other tales, which originated in other tales in an endless telling and retelling, and moreover, multiple tellings are the hallmark of this sort of folk-literature. Does it matter who told it first and how?

I enjoy imagining the storytellers who told the different versions of the tale sitting in a circle. One of them begins to tell the tale of Solomon, when another suddenly interrupts them, saying: “No! You’re telling it wrong. Your’e missing the best part: this is how you should tell it!” At which point they continue with their own version till they are interrupted by another, and so long and so forth—till no one remembers who told it first and each thinks they told it best.

Thus Spoke the Ant

A Tale of Solomon between Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ and Jewish Aggadah

Introduction

Muslims, Christians, and Jews in the pre-modern Islamicate world all participated in the creation of a shared narrative culture. The stories they told often transcended religious and communal boundaries. This is true of the fables discussed by the other panel members, and it is also true of legends about the Biblical patriarchs, prophets,kings, and other heroes of the past. But—as the question posed in the description of this panel asks—

“Do traveling characters, tropes and allegories shape-shift to reflect their immediate historical context, or do they carry multiple origins and layers of cultural exchange that defy spatial and temporal boundaries?”

Similar or identical stories may mean different things to different readers, both individual readers and entire audiences. The question I would like to pose here is rather simple: how do different narrating communities adapt the same narrative materials used by their neighbors to fit the needs and expectations of their own members? In what ways do “rival tellings of shared stories” (to paraphrase Robert Gregg’s book title) diverge from one another? And more specifically, how does a shared “cultural hero”—in this case King Solomon—is made to mean different things?

I will examine these questions by looking into some subtle and not so subtle changes between the variants of a single legend that was shared among Muslims, Christians and Jews. I shall focus on two main adaptation strategies:

- Narrative additions and omissions;

- Shifting intertextualities;

The Legend of Solomon and the Haunted Castle: Background.

In short, the legend I am dealing with tells of Solomon’s travels on his flying carpet and his encounters with several unlikely peers, each of whom teaches the king a lesson in humility. During his journey, he has an altercation with the wind, who rebukes him for his boastfulness (in some versions); he converses with the queen of the ants, who puts him to shame for his haughtiness; and he roams the haunted corridors of a magnificent castle, wondering about the fate of its erstwhile dwellers and the identity of the mighty ruler that had built it. The builder finally turns out to be an ancient and long forgotten king called ʿĀd ibn Shaddād (or in some versions Shaddād ibn ʿĀd).

There are several manuscript versions of the legend copied by Muslim copyists (to the best of my knowledge, all of them remain unedited). For the purpose of this paper, I will be relying on a manuscript version that I located in the collections of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, in an eighteenth century manuscript of a work of the Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ genre.

Versions of the tale copied by Christian scribes include an early version in Garshūnī (unavailable to me as of yet), and a version copied by an Arab-Christian scribe in the 17th century. This version was edited by Nabil Watad in his 2009 M.A. thesis (and I rely on his unpublished edition). This version further shows affinities to a version of the tale published by Louis Cheikho in al-Machriq in 1921, based on an eighteenth-century manuscript and to some other manuscript versions (which may have also been copied by Christian scribes, though this cannot be ascertained). To the best of my knowledge, Cheikho’s edition is the only Arabic version of the tale available in print. However, it went entirely unnoticed by scholars.

Finally, Jewish versions of the tale include both texts in Judeo-Arabic and a pre-modern Hebrew translation, titled Maʿaśeh ha-nemalah (“Tale of the Ant”). The Hebrew version was first published by Adolf (Aharon) Jellinek in 1873, in his collection of short midrashim, titled Beit ha-Midrasch. The dating of the Hebrew version is hard to determine, but it was probably copied no earlier than the 18th century. I should note that the Hebrew version is undoubtedly a translation from Arabic. This is evident from the linguistic character of the Hebrew text, from its use of Arabic nomenclature, and from some obvious calques.

Additions and Omissions: The Two Variants

So, what are the differences between the versions? And whar can they tell us about their creators and their audiences? The most conspicuous difference is the inclusion or omission of certain episodes in various versions. These inclusions and omissions are so consistent, that they allow us to divide the extent versions of the tale into two main variants.

Variant A, which includes the Muslim and the Jewish (Hebrew) version, begins with the episode of Solomon’s rebuke by the Wind. While flying on his fabulous carpet surrounded by his human and non-human hosts, Solomon boasts of his supreme reign, the likes of which have never been given to anyone. A sudden gush of wind throws several thousand men off the king’s carpet. The enraged Solomon flogs the carpet and orders the wind to settle down. The wind then rebukes him for his boastfulness, and the king lowers his head, ashamed. This episode of Solomon’s altercation with the wind is entirely absent from Variant B, which is represented by the christian text. The middle episode of the story—Solomon’s conversation with the ant, is almost identical in both versions (and I shall return to it later).

It is in the last part of the tale that the most meaningful divergence between the two variants occurs. In both, Solomon arrives at a magnificent castle built of gold and silver. While roaming its corridors and reading inscriptions that bemoan the fate of its inhabitants, Solomon wonders who could have built it. Variant B provides the answer to the king’s bewilderment through a story told to him by a supernatural inhabitant of the castle: a gigantic serpent-demoness. The demoness tells the king that the castle was built by an ancient king called ʿĀd ibn Shaddād and that he and all who followed in his footsteps died because of their wickedness, and ever since, the castle has been haunted by demons. Solomon then proceeds to vanquish the demons and clear the castle from the evil that infested it.

The demoness and her story are entirely absent in Variant A. Here, the answer to the mystery of the castle’s origins comes at the very end of the tale. After vanquishing the demons, Solomon finds a golden inscription hanging from the neck of a statue. However, he cannot decipher it. Suddenly, a mysterious young man appears “from the desert”. The young man tells Solomon that God sent him to relieve the king from his stress. He deciphers the inscription for him; it reveals the name of the castle’s original owner, ʿĀd ibn Shaddād (in the Hebrew version: Shaddād ibn ʿĀd), and admonishes the reader to renounce this world and its wiles.

A comparison of the two variants shows that each leads to a different interpretation of the image of Solomon and of the tale as a whole. With its solemn coda, Variant A ends as a tale of moral humility. In it, Solomon learns several moral lessons through his encounters with his counterparts: through his clash with the wind, he learns that he is not above the forces of nature; through his dialogue with the ant, he learns that he is no better than even the tiniest of God’s creatures; and through his encounter with the castle and its mysterious builder, he learns that he does not surpass those who came before him, that he is a mere mortal, and that his knowledge and wisdom, though vast, are limited. Thus, Variant A shapes the legend as a moral tale, whose sober lesson can be summed up in the words of Ecclesiastes: Vanitas vanitatum, omnia vanitas.

Meanwhile, in presenting the tale of the castle and its ancient dwellers as one of idolatry, wickedness, and transgression, Variant B sets up an inverse mirror before Solomon. The ancient idolatrous occupants of the castle are here interpreted as the moral opposites of the righteous king. Indeed, in both versions Solomon clears the castle from idolatry and frees it from the demons that infest it, but only in Variant B can these actions be interpreted as Solomon’s triumph over the past. It leads to an understanding of the tale as a story about the triumph of righteousness over sinfulness.

Shifting Intertextualities

There are other, more subtle differences between the two versions. Before I move on to examine one of them, I should address the question of the story’s origins. It seems most likely that the story took shape within a Muslim milieu. The main evidence for this are the tale’s multiple Qurʾānic references: first and foremost Solomon’s encounter with the ant (to which I shall return shortly), but also the fact that the story mentions Solomon’s dominion over the wind, the Jinn and the animals, as mentioned in several places in the Qurʾān. According to some versions, the name of the wind that would carry Solomon’s carpet was rūḫāʾ, a Qurʾānic term mentioned in Q. 38, v. 36. In fact, the affinity between the tale and the Qurʾānic portrayal of Sulaymān is so obvious that the tale can be considered as a narrative expansion of the terse Qurʾānic references to Solomon, or in other words, as belonging to the Islamic genre of Qiṣaṣ al-Anbiyāʾ or “tales of the prophets”.

As I mentioned earlier, the most striking Qurʾānic reference is in the second part of the tale. In this part, Solomon arrives at the Valley of the Ants (Wādi ‘l-naml). There he hears one of the ants warning its mates: “Ants, enter your dwelling-places, lest Solomon and his hosts crush you!” This description is based entirely on Q. 27, v. 17–18, which recounts the arrival of Solomon and his troops to the valley of the Ants (wādi ‘l-naml) and Solomon’s conversation with the ant. And indeed, it is hardly surprising to find that the muslim version quotes the Qurʾān verbatim at this point, after which it tells of Solomon’s and the Ant’s conversation, and how the ant (like the wind before it) rebuked Solomon for his haughtiness.

When looking at the christian version of the tale, it is rather striking that the Qurʾānic text is replaced with a paraphrase. This seems a deliberate attempt on the part of the christian storyteller or copyist to conceal the Qurʾānic subtext of the tale. Now, the Hebrew version of the tale includes an almost literal translation of the Qurʾānic verse. However, as the Qurʾān was unfamiliar to most pre-modern (and sadly also to modern) Hebrew readers, the Qurʾānic reference would have posed no real religious problem or threat to the translator, the copyist, or the intended readership.

Moreover, Jewish and Christian audiences could just as easily interpret Solomon’s encounter with the ant as a reference not to the Qurʾān, but to the Bible, and quite easily so. After all, ants are mentioned twice in the Book of Proverbs, a work traditionally attributed to none other than King Solomon himself. The story of Solomon’s encounter with the ant (and the ant’s moral reproof of Solomon for his boastfulness) would then be perceived as a narrative expansion—a midrash—of Prov. 6, 6, in which the wisest of all men instructs: “Go to the ant, thou sluggard; consider her ways and be wise”, and perhaps also of Proverbs 30, 25, which mentions the ants’ resourcefulness.

The biblical overtones of the tale are further accentuated in the coda of the Hebrew version, which has the inscription of the ancient builder say: ”For everyone is destined to die, and nothing shall remain at one’s hands save for [one’s] good name” — A line that reverberates the words of Ecclesiastes—again, a work traditionally attributed to Solomon: “A good name is better than precious ointment; and the day of death than the day of one’s birth”. This is also in line with Variant A’s moral message, which again can be summed up with the words of Ecclesiastes: Vanitas vanitatum, omnia vanitas.

Conclusion

The legend of Solomon, which had probably originated among Muslim storytellers around the middle of the second millennium CE, spread beyond Muslim audiences and was adopted by Jews and Christians. This legend, and others like it, was especially suited to be adapted by followers of all Abrahamic religions, not only because its hero appeared in the canonical texts of all of them, but moreover, because the adjustments required to pass it as a “jewish” or a “christian” tale were rather minor: these adjustments mainly meant replacing Qurʾānic references with parallel Biblical ones, and that, as I have shown, was easily achieved. Thus, the story could be read as a piece of Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, a midrash Aggadah, or simply a christian legend.

To return to the question posed at the beginning of this lecture:

“Do traveling characters, tropes and allegories shape-shift to reflect their immediate historical context, or do they carry multiple origins and layers of cultural exchange that defy spatial and temporal boundaries?”

The Answer is of course: both. There are constants in the image of King Solomon (and other cultural heroes like him) that do not change, such as his wisdom, his rule over human and non-human subjects, his ability to bind demons, etc. These are parts of Solomon’s literary iconography as explored time and again in modern scholarship. Though these attributes are indeed integral, almost organic parts of the literary portrayals of Solomon, their meaning or significance are open to interpretation and re-fashioning. Like other mythical or legendary heroes, Solomon’s stories can always be retold and his image can always be created afresh, to suit the needs of the time, place, and audience.

The two variants that I have examined reveal a double image of Solomon, one that is familiar from other sources and other legends as well: on the one hand a boastful king who learns a lesson in humility, and on the other, a powerful mage who triumphs over evil.

But here is where things get a bit sticky: do these conflicting images of Solomon necessarily reflect the attitudes of different communities or different audiences? For now, it is not entirely clear whether the “serpent episode” was part of the “original” (and not necessarily christian) version or an addition of a later storyteller. This leads to another open question: Can we or should we judge the “originality” of the tale? After all, this tale was born out of other tales, which originated in other tales in an endless telling and retelling, and moreover, multiple tellings are the hallmark of this sort of folk-literature. Does it matter who told it first and how?

I enjoy imagining the storytellers who told the different versions of the tale sitting in a circle. One of them begins to tell the tale of Solomon, when another suddenly interrupts them, saying: “No! You’re telling it wrong. Your’e missing the best part: this is how you should tell it!” At which point they continue with their own version till they are interrupted by another, and so long and so forth—till no one remembers who told it first and each thinks they told it best.