PDF

Download

Citations

Click and drag then release to select a passage to cite.

Annotations

How to submit annotations to Mizan Journal articles:

your work is published.

Search within

Editor’s Introduction

Context and Comparison in the Age of ISIS

Image

Audio

Video

Chart or Graph

Editor’s Introduction

Context and Comparison in the Age of ISIS

Public scholarship and addressing ISIS as media phenomenon

The Mizan initiative aims to address the pressing need to make the expertise of scholars of Islam available to a wider public, particularly by distributing original scholarship of contemporary relevance through digital channels on an open access model (that is, free of all restrictions on access and almost all on reuse).1 Undoubtedly, more conventional scholarly publishing outlets, whether university presses or private academic publishing houses, have achieved great success in utilizing digital media, networks, and distribution systems to disseminate the results of scholarly research more widely than was possible in the past. However, the Internet, particularly social media, has also to a great extent enabled the acute spike in Islamophobia and other forms of xenophobic expression in America and Europe over the last decade.2 Mizan aims at restoring the balance—to contribute to an improvement of online discourse about various facets of Muslim culture, both historical and contemporary, by making a range of material freely available on this website, including the peer-reviewed, open access journal of which this essay is a part. We firmly believe that promoting sophisticated but accessible scholarship aimed at a variety of audiences, addressing a variety of subjects, provides an important service to diverse communities among both scholars and the general public with an interest in the history, culture, and current developments in the Islamic world.

Given Mizan’s mandate to deploy scholarly expertise to illuminate events and phenomena pertaining to Islamic cultures, communities, and traditions—especially through analysis that provides historical context and fosters comparative inquiry—it has seemed particularly appropriate to devote our first issue to the subject of The Islamic State in Historical and Comparative Perspective. This is first and foremost due to the massive media profile of the ISIS movement, which combines features of an insurgency, terror network, and nation-state (at least aspirationally), with its ideology adroitly disseminated by an effective public relations machine skilled at exploiting both traditional and social media—particularly with gruesome acts of violence manipulated as political theater. ISIS’ successes, both on the ground and as a media phenomenon, have catapulted it into the global spotlight, and its continuing cultural prominence calls for responsible scholarly commentary.

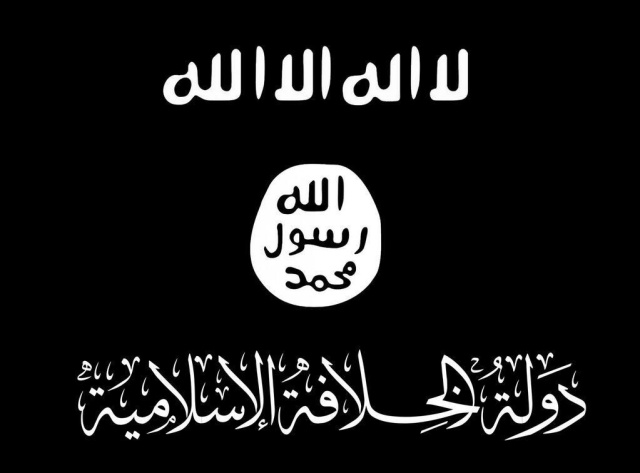

We have also felt that it is urgent to devote our first issue to analysis of the ISIS movement because of the specific nature of its ideology and claims, which reflect a complex, contentious, and highly problematic relationship to Islamic history and tradition—as demonstrated, for example, by its flag, which appropriates the image of the seal of the Prophet Muḥammad (see Gallery Image A). ISIS appeals directly to the worldwide Muslim public by claiming to have revived the Sunni caliphate of old, positioning itself as the sole legitimate political and religious authority for the global Muslim community. Despite this claim to universality, the movement paradoxically rejects the communitarian ideal traditionally espoused by Sunnis in favor of a puritanical perfectionism; further, it unhesitatingly sanctions acts of extreme violence against fellow Muslims whom it deems to be apostates, heretics, or infidels—a posture typically associated only with the most radical sectarian formations within the Islamic fold. Claiming to represent true historical Islam, ISIS thus presents a lethal threat to any and all voices of dissent, while simultaneously reviving a wholly anachronistic vision of a jihad state based on conquest and domination, its military successes supposedly validating claims of divine favor and moral rectitude as they once did for caliphs who lived over a thousand years ago.

Some efforts to analyze the rise of ISIS and particular aspects of its ideology, especially its claim to revive long-forgotten but essential aspects of Islam, have been controversial specifically because of the problem of authenticity. What qualifies ISIS, or any other movement that seeks to mobilize elements of Islamic tradition for political ends, to justifiably claim to be a genuine revival of the caliphate or any other traditional Islamic institution? What position should a responsible scholar take vis-à-vis such claims? Are these assertions, however anachronistic or anomalous, as valid as those of any other group, given that scholars have long been accustomed to emphasizing that Islam is not a monolithic thing, but rather must be understood as a plurality of diverse and sometimes contradictory ideas and practices?3 Or is the scholar obligated, particularly on moral grounds, to refute ISIS’ claims as not only illegitimate but actually un-Islamic?

A major factor in such considerations is ISIS’ almost unprecedented perpetration of startling acts of violence, overshadowing those of most terror organizations that previously enjoyed widespread media attention in ferocity and scope (except, perhaps, for the attacks committed by Al-Qa’idah against the United States on September 11, 2001). The persistence and brutality of ISIS’ field campaigns and oppression of conquered populations in Iraq, the regularity of terror attacks in the West committed in its name over the last two years, and its gloating revival of slavery and calculated attacks on cultural heritage sites in the territory under its control have earned it a degree of infamy dwarfing even that of Osama bin Laden or the Taliban, whose strategy and tactics now seem, depressingly enough, far milder in comparison, and their ideology far less pernicious. While the Taliban and Al-Qa’idah compelled both scholars and spokespeople for the moderate Muslim majority to relativize their atavistic fundamentalism and global jihadism as marginal and aberrant, ISIS’ commission of sadistic atrocities inspires even more energetic disavowals, provoking the question of whether some conceptions of Islam are so extreme as to be beyond the pale of what can justifiably be called Islam at all.

At least for a time, ISIS had significant success in recruiting fighters to join its ranks in Iraq and Syria, primarily through its deft manipulation of social media to disseminate its slickly produced propaganda.4 However, one might argue that this propaganda, projecting horrific imagery that seems to play on the world’s collective nightmares about Islamist violence, has had an even greater impact in triggering extreme reactions from both government and populace in various Western countries. The recent rise to prominence of far-right groups and spokesmen throughout Europe and even America—where the formerly mainstream Republican Party has recently begun to openly indulge white supremacist, Christian Identity, and ethnonationalist constituencies to an unprecedented degree—has been encouraged by ISIS’ visibility in the media landscape. ISIS’ propaganda is clearly tailored to play upon Western fears of an imminent Islamic threat, seemingly confirmed by sporadic terror attacks in European and American cities—even though the bitter truth of the matter is that the victims of ISIS’ terror campaigns are disproportionately Muslim by a very wide margin, their attacks on various communities in the Middle East having been vastly more devastating. Provocation of extreme responses in Europe and America—encouraging the perception of a state of ineluctable hostility between not only the West and the Islamic State but also majority populations and their Muslim minorities—may actually at this point be the primary function of the material generated and circulated by the ISIS propaganda office.

In the context of ever-escalating nativist and ethnonationalist rhetoric in Europe and America, it is disheartening to find voices in both traditional and new media claiming that ISIS is not marginal or anomalous at all, but rather epitomizes Islam—a claim that has provided significant traction and advantage in political campaigns for some organizations, even some in the mainstream, while also placing Muslim minorities at real risk of violence, not to mention providing justification for state-sponsored policies of discrimination and surveillance. ISIS’ persistent claims that its operation has revived the traditional model of the caliphal jihad state, including a number of long-abandoned practices, while repudiating virtually all of the common adjustments to modernity found in most contemporary Muslim communities worldwide, encourages polemicists’ grotesque portrayal of the movement as ‘real’ Islam, and ‘real’ Islam as something essentially un-modern, uncivilized, and medieval.

Thus, for many scholars and spokespeople, it is not rejecting the actual practices and ideas associated with ISIS that is the problem, for even the most conservative Islamic state actors and community spokesmen throughout the world have not hesitated to disavow it completely. Rather, the problem is how to responsibly describe ISIS, for when craven fearmongers claim that it represents not an outlier but the very essence of Islam, it can be all too tempting to simply reject ISIS as a total aberration that has nothing whatsoever to do with ‘real’ Islam, and sweep the problematic implications of such categorical disavowal under the rug. It was exactly this tendency towards disavowal that Graeme Wood sought to address in his much-discussed piece for The Atlantic, which sought to locate ISIS in an overarching trajectory of contemporary Jihadi-Salafi thought with recognizable, albeit problematic, roots in certain aspects of the classical and medieval Islamic mainstream.5

The controversy raised by Wood’s piece and other discussions of the ISIS phenomenon inspired a panel discussion on April 23, 2015 at the Pardee School for Global Studies of Boston University, “Interdisciplinary Approaches to the Islamic State.” The papers from that panel provided the kernel of this, the first issue of Mizan: Journal for the Study of Muslim Societies and Civilizations. The need for nuanced, balanced, and sensitive discussion of critical issues pertaining to the background, ideology, and propaganda of the Islamic State has only intensified over the last sixteen months, particularly in the lead-up to the American presidential election. This issue seeks to address that need, at least in some small way.

Approaching ISIS in broad comparative perspective

The visibility of ISIS, as well as the varied political and media responses to it in both the Western and the Islamic world, demands that scholars interrogate the complex intersections of historical memory (and amnesia), identity, religion, and politics that constellate in its claims and actions. The articles in this issue of Mizan deal, for the most part, with analysis of primary texts associated with ISIS, especially its propaganda magazine Dabiq. In addition, some of them deal with aspects of the varied responses to ISIS and its claims. None of them deal with the scattered instances of small-scale coordinated terror attacks in Europe in 2015 or 2016, or with the so-called ‘lone wolf’ or ‘wannabe’ attacks perpetrated in the United States by individuals with no tangible connection to ISIS through conventional networks, yet who have justified acts of violence by claiming ‘inspiration’ by the movement or pledging allegiance to it. However, it is important to take note of these attacks, at least in passing, for they have given right-wing parties in both Europe and America the most fodder for ethnonationalist rhetoric, often taking on conspicuously racist, chauvinist, and imperialist forms that at times evoke not only traditional nationalist tropes, but also triumphalist Christianity. This has been particularly true in America, where Republican candidates for office have made implicit or explicit appeals to evangelical support on the one hand, and exploited the now-shopworn tropes of the post-9/11 security state on the other, sometimes combining them in curious and provocative ways.

It is clear that scholars have a responsibility to subject these phenomena to analysis of a comparative or contextualizing sort, particularly in the classroom or in public outreach settings, where opportunities to correct fallacious or pernicious misconceptions abound. For example, a logical fallacy we commonly encounter in media discussions of Islam is the tendency to absolutize it as essentially violent or essentially peaceful. Not only are religions as abstract concepts incapable of being aggressive or peaceable, of course, but even when we speak of Muslims as individuals and communities possessing full human agency, to attempt to characterize all Muslims as having one or another personal quality, political orientation, or moral disposition is, of course, ludicrous. Rather, as is the case with all religions, the textual and traditional sources of Islam offer rich resources for believers to articulate diverse positions.

Some of those positions have been more typical and deemed normative by consensus than others, to be sure. However, we must surely acknowledge that tradition does provide a symbolic language to Muslims who seek to tighten the definition of who the real members of the community are, and thus supplies pretexts for fostering violence against those within the community who disagree with them. But insofar as such an insight implicitly challenges the position that ISIS has nothing to do with Islam—admittedly a farfetched claim—it is also useful to apply this insight more broadly, in seeking comparanda beyond the boundaries of Islam. Something that contemporary American polemicists fail to understand—or refuse to recognize—as they typify Islam as violent and Christianity as peaceful is that neither characterization holds up to close scrutiny. No religious tradition—or its all-too-human practitioners—can successfully avoid the extremes; no community on earth fails to encompass every human behavior possible. This is hardly an abstract observation; rather, direct historical evidence shows this to be true.

In my article in this issue of Mizan, I draw a direct parallel between the millenarian doctrine promoted in ISIS propaganda and that of a much older Islamic movement, that of the Fatimids, a Shi’i group that established a powerful caliphate that dominated North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean for two hundred years. The similarities between the Fatimids and ISIS are striking, and this comparison is especially useful because of the distinct differences between them—separated by a thousand years, each arose under completely different political circumstances, the former as one of many radical Shi’i groups fostering rebellion against standing Sunni authorities, the latter as an offshoot of the Iraqi insurgency that draws on specific trends in late twentieth century ideologies of political Islam (especially the militant posture of contemporary Jihadi-Salafi groups).

But there have been numerous Islamic movements that espoused millenarian ideas in support of statebuilding projects like those of the Fatimids and ISIS—including the Abbasids, the classical form of the imperial caliphate par excellence; the Almohads, who dominated North Africa and Spain in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries; and, it seems, the early Muslim community under Muḥammad himself. The apparent recurrence not only of apocalyptic but of apocalyptic specifically harnessed as a political ideology in Islamic tradition is a phenomenon that merits considerably more analysis. However, it must be emphasized that the exploitation of expectations of millenarian deliverance specifically as a means of legitimating an extreme sectarian position and violence against outsiders in the hopes of achieving a radical reconfiguration of society (or the world) has not been the exclusive purview of Muslim groups throughout history.6

For one thing, in their era, Islamic groups such as the Fatimids were hardly alone in embracing apocalypticism or claiming a millenarian role for their dominion. As Holland deftly demonstrates in his sweeping history of Europe and the Mediterranean in the tenth and eleventh centuries, Christian powers were repeatedly gripped with apocalyptic fervor at this time, and numerous statebuilding and imperial projects presented their military and political activities as hastening the coming of the Kingdom of God and the End Times. Holland’s account shows that as the Millennium approached (whether interpreted as the thousand-year anniversary of Christ’s birth or that of his resurrection instead), various regimes and potentates found the temptation to endow their claims to authority and pretexts for expansion with the halo of the numinous (and the inevitable) simply irresistible, and did so by smearing their opponents as Antichrist and presenting their own rule as hastening the Second Coming.7 It is also noteworthy that at least some contemporary scholars have begun to emphasize the role of religiously sanctioned violence in the spread of Christianity in Europe, particularly during the Carolingian age, during which time Christianity was forcibly imposed upon Germanic and Nordic populations.8 One recent attempt to demonstrate that this policy of aggressive subordination of pagans was a direct borrowing from Islam by Charlemagne himself has now been decisively refuted; there were ample factors present in Christian Frankish culture to account for the Carolingian ‘jihad’ as an internal development without, in effect, blaming it on Muslim ‘influence.’9

The irony in all this is palpable. The creation of Europe as we know it—geographically, culturally, politically—was arguably the result of a sequence of struggles at least partially inflected by millenarian beliefs, and indisputably the result of spreading Christianity by the sword. By contrast, a thousand years later, ISIS seek to unravel and ultimately erase the idolatrous legacies of European modernity—with its false gods of liberalism, tolerance, and church-state separation—by once again heralding the imminent advent of the apocalypse. But in doing so with the twin instruments of coercive violence and apocalyptic ideology, ISIS is not tapping into Islam’s medieval legacy; if anything, it is mirroring the troubled origins of Christian Europe.

Some might argue that the millenarianism and compulsion that marked medieval imperial projects in Europe were aberrant, not typical of or essential to ‘real’ Christianity. It is certainly extremely common to find ideologues drawing a negative comparison between Christianity and Islam on the basis of the contrast between the pacifism of Jesus on the one hand and Muhammad’s supposed resort to the sword on the other—the image of the founder thus supplying the ideal that defines the faith, however disparate the realities might be.10 It may otherwise be argued that the appeal to apocalyptic and messianic rhetoric, or the resort to compulsion in the spread of Christendom, was superseded by the more enlightened and secular ideologies that motivate the political and military agendas of Western nation-states today. This is the crux of the common polemical claim that Islam remains backward and medieval while the West has progressed into modernity, despite the actual decline in secularism (at least in the United States)—the outlook that supposedly marks the absolute criterion of difference between a regressive Islam and Western modernity in discussions of Islam’s need for ‘reformation.’ However, it is not difficult to find contemporary Western analogues to this ‘medieval’ aspect of Islam as well.

For one thing, in the eyes of many Muslims, Western colonialism and imperialism have a distinctly religious aspect to them, even if many Europeans and Americans would disagree. The common denial of the association of Christianity with projects of domination, political expansion, slavery, even genocide, cannot withstand critical scrutiny; decades of deconstruction of the Bible and its use to promote such agendas provides ample evidence that the facile distinction between an Islam that is at its root diminished and invalidated by its association with the sword and a conveniently depoliticized Christianity simply does not hold up.11

This perspective is worth considering because some scholars and critics have suggested that the foreign policy of the powerful Western democracies in the twenty-first century, in particular the so-called War on Terror prosecuted by the United States and allies like the United Kingdom, displays aspects of the very apocalyptic millenarianism that is supposedly eschewed by the modern secular state—and that America supposedly seeks to combat in ISIS.

Northcott’s study An Angel Directs the Storm offers a potent critique of the messianic underpinnings of the War on Terror during the Bush administration: the apocalyptic imperialism that shaped policy; the antidemocratic drive to consolidate power in the hands of the executive branch to support an absolute struggle against America’s enemies; and the relentless expansion of a frontier marked by violent confrontation that continues to justify keeping America on a perpetual war footing today. Northcott argues that the administration played on a new interpretation of the Christian “Kingdom of God” as a divinely-ordained mission in pursuit of global hegemony, one that was secular in orientation, at least on the surface, but that drew on ancient and perennially effective appeals to Christian triumphalism.12

Northcott’s work complements Lincoln’s compelling study of the use of religion in American political rhetoric at the outset of the War on Terror. Lincoln’s analysis of the speeches of Osama Bin Laden and George W. Bush on October 7, 2001 reveals the deep religious subtexts of both; in particular, Lincoln’s deft deconstruction exposes Bush’s subtle appeal to evangelical Christian supporters through carefully coded evocations of eschatological, providential, and messianic concepts.13 Given the tragic history of American military interventions into Muslim societies in the last fifteen years, the rhetoric of a millenarian caliphate like ISIS, with its clear goal of legitimating state violence, is in the final analysis not so different from the neoliberal messianism used to authorize contemporary Western imperialism and state terror—enabling the paradoxical claim to safeguard the world for freedom and democracy through bombing campaigns, drone strikes, and military occupation.

The millenarianism of official organs of the American state is at most only implicit: Lincoln is at pains to point out that the evangelical messaging embedded in Bush’s speeches was carefully telegraphed to supporters sensitive and sympathetic to it, but remained covert in order to avoid openly promoting such ideas, since this would have corroded the administration’s legitimacy in the eyes of secular-minded Americans. However, other elements in the American political system, particularly Republicans less concerned with alienating the secular mainstream and more concerned with securing the support of the evangelical base, have in recent years come to a more or less open embrace of apocalypticism. Thus, in spring 2015, former Representative and Tea Party activist Michele Bachmann (R-MN) gave multiple interviews to right-wing Christian media outlets opining that the Rapture was imminent, a direct result of the Obama administration’s impending nuclear deal with Iran, as well as the advances made toward the universal legalization of gay marriage in America.14 This can hardly be considered a fringe tendency when such ideas are openly espoused by members of Congress or the surrogates of contenders for a major party nomination for candidacy for the American presidency, seeking to stoke evangelical support by promising a quasi-messianic return to a theocratic utopia should their candidacy prove successful.15

In this, the Tea Party appears to be as conspicuously sectarian as ISIS—if perhaps ultimately less successful in establishing itself as a major player in national or international politics. It may be easy for many Americans to dismiss these ideas as fringe and unworthy of serious attention in comparison to those parallel views which seem to have had much greater impact in inspiring ISIS. But one cannot ignore the fact that such political millenarianism has traction for certain constituencies under certain political circumstances, and that the success of one group and the marginality of another may be determined, in the final analysis, by differing material, political, and social conditions—and not much else. Millenarian views may not be as widespread in America as they are in Iraq, but they certainly are widespread; that a fringe apocalyptic group has not seized control of the United States government as ISIS has sought to wrest control of Iraq from the current regime surely reflects America’s economic prosperity, institutional stability, and the continuing durability of its civil society, and not an intrinsic immunity to extremist belief systems grounded in a selective reading of aspects of its majority religion.

One might argue that when American politicians make explicit religious appeals to their supporters, they are simply playing to the heavily millenarian belief system openly embraced by Christian evangelicals, including the religious or quasi-religious Zionism that is a mainstay of contemporary Republican ideology. Promoting this worldview also has the felicitous benefit of exploiting a kind of Manichaean belief in a world dominated by the struggle between good and evil; this has clear utility as a form of political theater that plays well in the American media and appeals to a certain demographic. But reducing this to mere theater or propaganda in no way reduces the validity of comparison with ISIS: we know nothing of its leaders’ convictions, only what forms of rhetoric seem to have appeal for their supporters and the types of discourse that prove effective for recruitment.

Moreover, the embrace of a radical dualism that reduces problems to a fundamental, even cosmic, struggle between good and evil is especially beneficial for an opposition group that is primarily concerned with harnessing anti-establishment hostility to promote their agenda, and is for the most part largely unconcerned with the pragmatic considerations of actual governance.16 The simplistic ideology of ISIS that flattens the world, rendering the complexities of global politics into a struggle between a pure Muslim elite and a host of threats from both insiders and outsiders, is much more effective as a recruiting tool for a disillusioned and alienated fringe of Muslim society—especially individuals already prone to violence—and much less effective as an ethos that can sustain a stable statebuilding enterprise. This is equally true for the Christian dualism evoked by some American politicians, similarly grounded in end of the world fantasies; it is far easier to blame a complex, chaotic world on outsiders or diabolical forces than it is to confront the public with uncomfortable truths about problems that require resourcefulness and complex, difficult solutions.

This is precisely why the right wing in American politics that embraces millenarianism stridently denies the reality of climate change, insofar as this is an explanatory mechanism for global problems that is not only grounded in science (and not the supernatural) but that calls for accountability on the part of citizens and institutions alike. Insofar as the problems at hand have been caused by our own overconsumption, overpopulation, and overtaxing of the world’s limited natural resources, with corporations and public institutions entirely complicit in making the problems worse, a Manichaean-style dualism is hardly adequate for coming to grips with the problem in a realistic fashion.17 Here we come full circle, for the Syrian political crisis that led to the country’s decline into civil war in 2011—and thus enabled the rise of ISIS—was allegedly preceded and triggered by a climate-related crisis, stemming directly from the unrest and instability that were repercussions of a drought that wracked the country from 2006 to 2009, displacing hundreds of thousands of people and causing millions of livestock animals to perish of starvation and thirst, abandoned by farmers who had no choice but to flee to already overcrowded and overtaxed urban areas.18

Further, one can hardly maintain that ‘radical Islam’ has a monopoly on the use of divisive language of radical ‘othering’ such as we observe ISIS using in its propaganda, designed to legitimate the oppression and victimization of its fellow Muslims. British Prime Minister David Cameron’s reference to ISIS as a “death cult” was admirably motivated by a desire to distance the extreme acts of the movement from ordinary Muslim citizens—essentially operationalizing the critique of ISIS as beyond the pale of true Islam as an aspect of public relations and government policy. But the invocation of the language of ‘cult’ specifically is ironic given the background of this term in historical Euro-American responses to alternative religious formations, particularly movements that tend towards more extreme expressions of eschatological fervor. Scholars of religion no longer use ‘cult’ as a reliable descriptive term; rather, it is now widely recognized as a political construct intended to mark a group not only as deviant but subject to extreme sanction by government agencies (the Branch Davidians of Waco being the most obvious example). The language of ‘terror’ serves much the same purpose.

While American and British administrations may mean well in seeking to delineate ‘real’ Islam from deviants who commit violence in its name, the disquieting consequence is that the state takes on the responsibility of arbitrating in such matters, arrogating to itself the role of deciding which forms of religiosity are or are not legitimate—with life and death often literally hanging in the balance. Just as ISIS uses coded language to mark Shi’ah and noncompliant Sunnis as infidels whose blood can legitimately be shed, the use of the language of ‘cult’—especially ‘death cult’—seems tailored to prepare the public for absolute war against the implacable evil of ISIS, without regard for the potential cost in civilian casualties. (Ironically, the relentlessly apocalyptic vision presented by speakers at the Republican National Convention in July 2016 prompted one commentator to characterize the Republican Party itself as a kind of death cult.19)

Exposing the historical connections between Christianity, ideologies of imperialism and triumphalism, and the fostering of discursive and bodily violence against various ‘others’ is hardly necessary to establish a moral basis for objecting to such positions. But it is perhaps important to explicitly articulate that the historical and contemporary association of Christianity with empire-building and the legitimation of violence does not constitute a refutation of Christian principles as expressed by the majority of Christians, let alone justify marginalizing people who embrace its tenets. It is self-evident, even banal, to note that the same consideration should apply to Muslims. But even-handed approaches to and representations of Islam continue to be frustratingly elusive in the current American political environment, in which calls for the closing of the borders to Muslims and even oaths of loyalty and “shari’ah bans” have come from some of the most high-profile politicians associated with the Republican Party.20

Another irony emerges here, for the political discourse and strategic communications that have emerged around the Republican candidate for president in the 2016 campaign mimics that of ISIS in disturbing ways. Donald Trump’s campaign—and Republican cadres in general—seek to mobilize support among right-leaning constituencies through indulging in extreme nativist and xenophobic rhetoric. They present a worldview in which such supposedly distinctly American values such as freedom and democracy are wholly incommensurable with Islam, and thus imply an ongoing state of potential, and at times actual, hostility between America and the Muslim world, supposedly typified by radical movements such as ISIS (and supposedly confirmed by the actions of lone wolf radicals such as the Orlando and San Bernadino shooters). In defiance of the increasing aversion in official channels to indulging in damaging ‘Clash of Civilization’-type rhetoric or typifying the actions of marginal groups and individuals as characteristic of all Muslims, the Trump campaign and its proxies insist on depicting ‘radical Islam’ as an existential threat, a tactic that is the functional equivalent of ISIS’ attempts to exacerbate tensions between Western societies and their Muslim minority populations. Both seek to alienate Muslims from their home societies in Europe and America and exploit anxieties about irreconcilable conflict for political advantage.21

Similarly, the media proxies of the Trump campaign have elaborated a complex coded language that is in its own way just as strongly sectarian as that found in ISIS propaganda, designed to promote an image of insiders as virile, prosperous victors and opponents as servile, submissive, emasculated, and ripe for defeat. This is an extension of the type of rhetoric the candidate himself uses even in day-to-day speech, like his frequent reference to critics, especially women, as ‘disgusting’; the political implications of the imagery of bodily revulsion as a form of total rejection has been widely remarked in a variety of contexts.22 The official and unofficial organs of the Trump campaign valorize aggressive, even predatory behavior: on social media, supporters are termed ‘centipedes,’ playing upon the insect’s capacity for stealthy, venomous attacks against its prey.23 As was widely documented during early 2016, the candidate himself repeated encouraged violence against protestors at his rallies during the primary campaign. Online, his joke about turning protestors out into the cold without their coats has been turned by his proxies and supporters into a trope, with ‘give the man a coat’ becoming a compliment, based on the idea of stealing said coat from anyone who opposes or criticizes him.

Further, the gloating, gendered triumphalism of ISIS and its spokesmen—who mock their opponents as “quasi-men,” even when they are (purportedly) women24—is echoed in the hypermasculine discourse of Trump supporters on social media, where the default term for Trump’s opponents is “cuck” (short for cuckold), with the intentionally degrading and racist associations sometimes left implicit, and sometimes not. The use of this term seems to have originated a number of years ago with the coinage “cuckservative,” an insult applied to Republicans deemed insufficiently conservative (similar to the code word RINO, “Republican In Name Only”), but “cuck” has quickly been expanded from being a term of internal critique within the Republican fold to being more widely applied, especially to liberals and socialists, who supposedly epitomize the self-abnegating, humiliating posture the term is meant to capture.25 The open chauvinism of the candidate himself, as well as the puerile and hypersexualized behavior of many of his supporters, led many to question the sincerity of his attempt to represent himself as the champion of gay Americans after the June 2016 Orlando shooting; given the policies Republicans openly endorse, as well as the cultural climate they foster, it is implausible that a Trump presidency would do much to benefit LGBTQ citizens.26

Perhaps the most bizarre turn in the 2016 campaign has been the overt turn to explicitly religious language, especially attempts to literally demonize the opposition. Trump has repeatedly made allegations about Hillary Clinton’s corruption and criminality (leading to the recurring rallying cry of “Lock her up!” at his events, as well as insinuations by his proxies that she will be tried and executed upon Trump’s inauguration as president), but this has recently escalated to a straightforward claim that Clinton is literally the Devil.27 This sort of name-calling is unprecedented in modern American presidential campaigns; the Trump campaign’s capacity to vilify the opposition seems limitless, as, for example, when the candidate himself repeatedly asserted that Obama and Clinton were the literal founders of ISIS, only significantly later downplayed as a sarcastic rhetorical move.28 Such rhetoric obviously plays to the enthusiasms of the Republican base, at the very least granting the candidate political traction among a vocal minority who indulge in fantasies of incarcerating or even executing Clinton.

This rhetoric has a subtler effect as well, in that it serves to locate the candidate in the camp of those fervent Christians who see in Barack Obama in particular and the Democratic Party in general a concerted campaign against their religion; the open indulgence in religious rhetoric of a theatrically excessive but symbolically resonant sort implies a similarity in worldview to those who already read partisan political struggles in theological terms. This alignment of the Trump campaign with right-leaning Christians—despite the candidate’s historically profane character and questionable personal rectitude—has also been encouraged by his hinting at a willingness to repeal firewall laws protecting the separation of church and state such as the Johnson Amendment. The alliance with evangelical elements eager to gain political advantage by allying themselves with Trump has proceeded to such a degree that, in breaking with the well-established tradition of pastoral neutrality in public political settings, the benediction delivered by the Reverend Mark Burns on the opening night of the Republican National Convention explicitly called on God’s assistance to defeat the “enemy”—openly specified as Clinton and the Democratic Party—while referring to the gathered assembly as “the conservative party under God” and praying for “power and authority” to be bestowed on Trump.29 The energetic vilification of political rivals in openly religious terms is of course a staple of ISIS propaganda; a particularly striking parallel appears in ISIS’ attacks on Jabhat al-Nuṣrah, upon whom ISIS spokesmen literally called down the curse of God in a dispute with their former allies.30

Extending our comparative analysis still further, if we seek to consider with equanimity all worldviews that emphasize the categorical boundaries between insiders and outsiders, investment in a messianic figure and anticipation of imminent and final judgment that will usher in a new golden age, a radical embrace of violence, and a reliance on scriptural themes, especially symbols and code-words, then these traits appear to describe not only ISIS but also certain virulent fringe elements in contemporary Judaism as well. The fact that most historical Jewish communities have not had access to state power has tended to impede recognition of the importance of holy war traditions in Judaism, although the work of Firestone in particular has done much to correct the misconception that Jews have not articulated religious justifications for violence.31 Likewise, for complex political reasons, the significance of Jewish terrorist movements in modern history is seldom recognized, and terrorism does not occupy the same place in discussions of contemporary Judaism that it does in discussions of contemporary Islam—despite its significance in certain contexts, in particular the foundation of the state of Israel.32 Thus, locutions such as ‘violent Zionism’ or ‘radical Judaism’ have nowhere near the same currency among Western commentators on Middle Eastern politics (let alone the general public) as ‘radical Islam’ and other expressions of that sort.

Nevertheless, it is clear that in the modern era certain actors have invoked Judaism, a tradition typically presented as exempt from such tendencies, to support radically exclusionary ideologies of a messianic nature, to not only foster violence against dehumanized outsiders, but to support expansionist political projects. A particular disposition to such radical ideology can be seen in certain wings of the Israeli settler movement, which justifies expansionism through such religiously-inflected conceptions as the “redemption of the land.”33 Further, both Firestone and Claussen have written about the significance of the thought of Yitzḥaq Ginsburgh in supporting the ideology of what we might call the Jewish jihadist fringe of the settler movement operating in the Occupied Territories, often committing violence in the name of Judaism, and often with impunity.

Ginsburgh’s teachings are of particular interest because of the way in which he amalgamates biblical narratives and symbols with a virulent political message, reminiscent of ISIS’ use of qurʾānic themes and images drawn from early Islamic history. Thus, following the reading of the notorious right-wing rabbi Meir Kahane, Ginsburgh holds up Pinḥas, the grandson of Aaron who zealously killed a fellow Israelite and the Midianite woman with whom he illicitly consorted (Numbers 25), as an ideal for faithful Jews to emulate. Interpreting the kabbalistic principle of tiqqūn ʿōlam (‘repairing the world’) as a mandate to undertake unconventional, even extreme, behavior to defend the Jewish people and sanctify their homeland, Ginsburgh and other figures of the Zionist ultra-right invoke this principle to justify the forced expulsion and killing of Arabs not only on grounds of self-defense or for the sake of national self-determination, but even as a holy act.34

These ideas do not appear in a vacuum, of course; rather, they present only the most explicitly religious justifications for violence on the part of state and quasi-state actors in Israel, particularly in contested areas such as the Occupied Territories—the main arena for Israeli expansion through settler groups acting as state proxies. Thus, Kahane’s ideas inspired Baruch Goldstein (whom Ginsburgh has openly defended), the perpetrator of the Cave of the Patriarchs massacre in 1994 in Hebron. Of course, the majority of Israelis would reject Ginsburgh’s ideology as a perversion of Judaism—just as the vast majority of Muslims abhor ISIS’ distortion of Islam. The difference in media representation could not be more stark, however: ISIS is presented as a virtually existential threat to Western democracy and freedom (and implicitly, to American hegemony in the Middle East); by contrast, the settler movement is only infrequently mentioned in the media, and the virulent aspects of the ideology of settlers is seldom acknowledged, despite the considerable impact the movement has had—and continues to have—on Israeli politics, demographic and political realities in the Occupied Territories, and thus, at least indirectly, on American policy and interests in the region.35

Perhaps the most significant counterargument to claims by Western analysts that the ISIS phenomenon represents something pernicious within Islam’s essence, a pathological tendency towards violence that marks an absolute distinction between Christianity and Islam, or ‘Western civilization’ and Islam, is presented by the phenomenon of American Christian jihad. Over the last two years, a number of journalists have reported on the Dwekh Nawshā, a Christian militia fighting ISIS in the northern Iraqi theater of war. What is significant about this militia group is that although it is primarily made up of Assyrian Christians native to the area acting in support of the larger and better organized Kurdish peshmurga, like ISIS, they have attracted a small group of foreign fighters as well, and these have predominantly been Americans, most of them with genuine military experience.

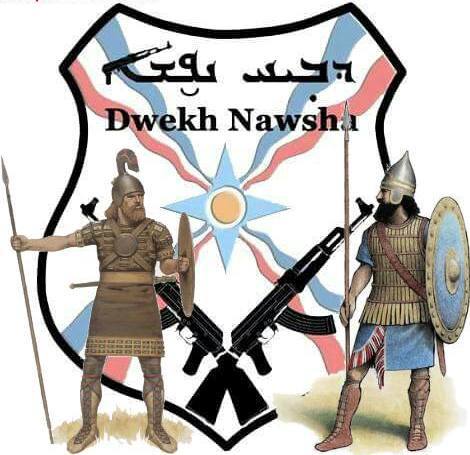

Many of the Americans who affiliate themselves with Dwekh Nawshā as volunteers express a combination of religious and political motivations for their immigrating to the theater of war. They often seem to construe their actions as defensive, though this is how Muslim jihadists have always presented their emigration (hijrah) to fight in various hotspots around the world where Islam is perceived as being under attack, whether it is Afghanistan, Bosnia, Chechnya, or now Iraq and Syria.36 It is unclear whether these American jihadists mean to martyr themselves as many of ISIS’ fighters do, though the name of the group is telling in this regard; dwekh nawshā means ‘self-sacrifice’ in Aramaic, and some of the American fighters mix militant nationalism and Christian religious symbolism in their self-presentation, though the Dwekh Nawshā organization itself (which also labels itself the Assyrian Army) seems to eschew explicitly Christian imagery (see Gallery Image C). Notably, even though the media coverage of foreign fighters from the United States often implies that their efforts are futile or even foolhardy, their motivations are typically portrayed in a positive light, especially through an emphasis on their desire to contribute to defending Christians against Islamic aggression. They are never recognized as another aspect of the original imperialist project that established an American presence in Iraq and Afghanistan—the theaters in which most of these foreign fighters first acquired military experience and expertise.37

The relationship between the various elements I have drawn together here is sometimes unclear. For example, not all apocalyptic movements necessarily embrace violence, though they often seem prone to this—or are at least prone to be exploited to foment and justify violence. Not all are expansionist or even inclined towards collective political or military action, though many of them certainly are. Perhaps it is that apocalypticism is such a useful instrument for constraining and redirecting social elements prone to violence that it has simply been expedient for expansionist states to attempt to harness it. Whatever the case, one thing is clear: Islam is not the only one of the monotheistic traditions in which combinations of violence, millenarianism, and a radically exclusionary ideology has been used to drive military action in support of political projects. ISIS is perhaps unusual in the extremity of its views and in combining a number of different elements in its ideology, but as I have shown, there is considerable overlap between its rhetoric and propaganda and that of other groups and movements throughout history. Upon deeper analysis, we find that no community is completely exempt from apocalyptic or hypermilitant tendencies, or lacking members who seek religious justifications for their extreme acts. We should thus seek explanations for the emergence and popularization of radical ideology not in the ‘essence’ or roots of a religion, but rather in the material causes and particular circumstances that engender it, and drive some believers to marshal whatever resources their religion might offer to support and legitimize violence.

Contributions to this issue

The articles included in this issue primarily stem from the aforementioned panel held at the Pardee School for Global Studies at Boston University in April 2015, “Interdisciplinary Approaches to the Islamic State.” Kecia Ali, Thomas Barfield, and myself presented early versions of our articles as papers on that panel, and Jessica Stern, Franck Salameh, and Kenneth Garden not only responded to our respective papers, but have also been kind enough to rework their comments into brief response papers that have also been included here. The additional articles, one by Jeffrey Bristol and another by Tazeen Ali and Evan Anhorn, were submitted for inclusion in the issue later. Overall, these articles represent diverse approaches to the ISIS movement, its rhetoric, and its relationship both to historical aspects of Islam and contemporary social and political expressions of Muslim belief, including responses to the claims and actions of ISIS itself.

Although there have been a number of publications on ISIS over the last two years, most of the peer-reviewed scholarship on the phenomenon has come from policy-oriented disciplines such as Political Science, International Relations, and so forth. We believe that this issue fills a conspicuous gap in the existing literature in offering scholarly perspectives from the Humanities and Social Sciences, particularly Religious Studies, History, and Anthropology. The offerings here are deliberately eclectic, united mainly by their common interest in interrogating not just the claims and ideology of the Islamic State, but the critical issues pertinent to the study of Islamic tradition and Muslim history and culture that are raised by such inquiry.

Kecia Ali’s contribution, “Redeeming Slavery: The ‘Islamic State’ and the Quest for Islamic Morality,” examines the contrasting claims of ISIS propaganda on the one hand and the “Open Letter to Al-Baghdadi” on the other on the question of the permissibility of slavery—one defining the practice as essentially un-Islamic, the other as paradigmatically Islamic. Ali demonstrates that a number of critical questions converge on this issue, including the cultural and political contexts in which sexual violence is categorized and represented and how tradition may be defined and contested through attempts to delineate what is or is not “Islamic.” Notably, although ISIS propaganda approaches slavery as an indelible and essential part of Islam, its approach to the juristic issues raised by the practice, of which ISIS’ audience is inevitably ignorant, actually underscores slavery’s anomalous nature. Jessica Stern’s brief response to this article explicitly challenges the claim that ISIS’ violation of standards of international law, morality, and common decency must be defined as ‘Islamic’ simply on the basis of the group’s use of sacred texts and reference to tradition to legitimate them; she points out that this is a strategy that many different sorts of radicals, including Jewish and Christian radicals, adopt to justify extreme acts and cloak them in the veneer of tradition. Deeper investigation of ISIS’ practices of organized rape and plunder shows that they do not necessarily stem from an ideological core, but rather help the group to fulfill specific pragmatic and programmatic goals.

In my article “ISIS, Eschatology, and Exegesis,” I attempt to place aspects of the use of tradition in ISIS propaganda in deeper historical context, comparing the interpretation of specific qurʾānic topoi, particularly Noah’s Ark, in Dabiq, the ISIS propaganda magazine, with that found in the propaganda of the Fatimid Empire. Although the Fatimid dominion flourished a thousand years ago, the comparison of ISIS with this Isma’ili Shi’ite state is productive insofar as it shows that groups adopting a radical sectarian position, especially by seeking to foment violence against their fellow Muslims in the pursuit of statebuilding projects, must employ a specific kind of reading strategy— a sectarian hermeneutic—in deploying the Qurʾān and symbols and themes from Islamic history to support their positions. The comparison of the early Fatimids and ISIS yields especially compelling results given that both groups support an extreme sectarian ideology with the claim of fulfilling prophecy by bringing events in an apocalyptic timetable to pass. The point is not to paint ISIS as somehow crypto-Shi’ite, but rather to delineate a specific kind of sectarian logic that shapes particular ideological claims and tends to rely on particular methods. As Kenneth Garden emphasizes in his commentary on my piece, pace those who seek to depict ISIS as representing true or essential Islam, the group actually employs reading practices that not only legitimate the use of violence against other Muslims but openly confirm its minority status, even celebrating it; ISIS spokesmen at one and the same moment accept that most of their coreligionists reject their message and exploit this fact as confirmation of their role as harbingers of the End Times.

The next contribution in this issue, “ISIS: The Taint of Murji’ism and the Curse of Hypocrisy” by Jeffrey Bristol, focuses on the background and development of a single aspect of ISIS’ messaging in its propaganda, namely its reliance on the codeword “Murji’ite” in its polemic against the Muslim mainstream. In fulminating against Murji’ism as a supposedly perennial heresy in Islamic history, ISIS propagandists skillfully draw on a traditional set of ideas and claims about this oft-maligned school of thought—including recent developments in jihadist ideology antedating the emergence of ISIS—and take them in new directions. The specter of Murji’ism becomes an evocative, multifaceted instrument in ISIS’ sectarian toolbox, serving the especially critical function of casting mainstream, accommodationist Muslims who refuse to align themselves with ISIS and its extreme positions as themselves members of a heretical group, the authenticity of whose Islam is supposedly questionable.

Thomas Barfield’s “The Islamic State as an Empire of Nostalgia” places ISIS in the broadest possible context, analyzing its caliphate as an exemplary case of a type of secondary empire that seeks to propagate its authority not on the basis of controlling significant territory or resources, but rather by capitalizing on the claim to have restored institutions associated with an alluring golden age. The symbolic self-presentation of the ISIS caliphate evokes precursors from Islamic history, particularly the Abbasid dynasty, during whose rule the imperial hegemony of Islam was at its most robust. Barfield specifically contrasts ISIS’ strategic appeal to this older caliphal golden age, at once political and religious in nature, with the secular state ideology of the Ba’ath and other groups that dominated the Arab-Islamic world during the flourishing of the nation-state system throughout the Middle East in the twentieth century. The appeal to a transnational Islamic identity has been crucial for ISIS’ attraction of foreign fighters to its cause, transcending the narrower interests more directly in play in the Syrian conflict and the domestic struggles that have wracked Iraq since the withdrawal of American forces in 2007. In his response, however, Franck Salameh cautions us to recognize that the appeal to an Islamic golden age has always undergirded the supposedly secular ideology of modern Arab nationalism, which long capitalized upon a form of nostalgia for Islam as the essence of Arab identity and its empire as the apogee of Arab accomplishment.

Finally, “ISIL and the (Im)permissibility of Jihad and Hijrah,” co-authored by Tazeen Ali and Evan Anhorn, adopts yet another perspective on the Islamic State phenomenon, again by bringing ISIS propaganda into conversation with the “Open Letter to Al-Baghdadi.” Taking a different approach than that adopted in Kecia Ali’s discussion, the authors examine these documents as evidence of the larger problems attendant on the question of Muslim belonging in Western states. They argue that both ISIS and Western groups (including Western state authorities) play upon Western Muslims’ anxieties about their place in American or European society and construct different but analogous ideals of Muslim identity: ISIS presents allegiance to its cause and disavowal of citizenship in Western democratic states as a necessary criterion of Muslim identity, while Western states and media impose a requirement of absolute disavowal of ISIS and public or semi-public expressions of loyalty and patriotism upon its Muslim citizens. In the latter case, this has the effect of delimiting the permissible parameters of political discourse, making social trust contingent upon an admission that religion is the ultimate wellspring of conflict—that is, that conflict stems from Islam, or bad interpretations of Islam, rather than from material, political, or societal causes. Notably, the authors draw upon the classic theories of the sociologist Max Weber concerning the role of charisma and institutionalization in society, contrasting the charismatic claims of ISIS with the reconfiguration of charisma in the cultural and institutional resources that Muslim communities may draw upon in articulating a unique and stable place in Western civil society.

In these articles, no attempt has been made to unify terminology. We have permitted the contributors to select whatever nomenclature for the entity that calls itself al-dawlah al-islamiyyah fī’l-ʿirāq wa’l-shām (the Islamic State of/in Iraq and Greater Syria) they believe is best (e.g. ISIS, ISIL, the Islamic State, Daesh, etc.) While steps have been taken to ensure that ISIS publications are cited responsibly, especially for the purpose of exposing the movement’s claims to critical analysis, on account of their nature as political propaganda of an aggressive state that has violated international law repeatedly in supporting or directly perpetrating terrorism, human trafficking, and destruction of cultural heritage, we do not provide direct links to the online sources of these publications. The Clarion Project (www.clarionproject.org) archives ISIS publications in English; further, original translations of materials pertaining to ISIS, including transcripts of videos and other media materials, can be found at www.jihadology.net.

Notes

All digital content cited in this article was accessed on or before September 21, 2016.

[1] Earlier drafts of this material were reviewed by Ken Garden, Will McCants, and Stephen Shoemaker, and later versions by Megan Goodwin, Kecia Ali, Olga Davidson, and Elizabeth Pregill. Their advice has been invaluable in helping me to shape what this essay has become. Naturally, I am responsible for the faults and flaws that remain.

[2] This has not occurred spontaneously, of course; as Bail and others have observed, significant moneyed interests exert a titanic influence on American perceptions of Islam, particularly by manipulating media representation of current events to fit well-established and highly prejudicial narratives about Muslims: see Christopher Bail, Terrified: How Anti-Muslim Fringe Organizations Became Mainstream (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014). The work of Bail is especially useful insofar as much of the literature on Islamophobia addresses cultural attitudes, social dynamics, and media representation, but overlooks the specific institutional contexts in which ideas and images about Muslims are actually generated and disseminated.

[3] The conception of “Islam” as essentially undefinable and comprehensible only as a body of concepts, practices, and discursive positions vis-à-vis a highly malleable and selectively accessed tradition is most closely associated with Talal Asad; see his recent methodological statement “The Idea of an Anthropology of Islam,” Qui Parle 17 (2009): 1–30.

[4] ISIS’ media output seems to have been most robust during the year from spring 2014 to spring 2015 when both its recruitment of fighters on the ground in Iraq and Syria and its military advances were most successful. For various reasons, its media output has actually declined since then, although its profile in the Western media has seemingly increased in response to the sporadic terror attacks that have been perpetrated in its name (or at least for which its spokesmen have sought to take credit). See Aaron Zelin, “ICSR Insight: The Decline in Islamic State Media Output,” ICSR.info, April 12, 2015.

[5] Graeme Wood, “What ISIS Really Wants,” The Atlantic, March 2015. Most of the contributions to this issue, including my own, address the problem of nomenclature and characterization from a variety of angles; many of them cite the controversy over Wood’s article as a touchstone for navigating these issues. For two radically different opinions on the problems provoked by ISIS’ very name, compare William McCants and Shadi Hamid, “John Kerry Won’t Call the Islamic State by its Name Anymore. Why That’s Not a Good Idea,” Brookings.edu, December 29, 2014 and Carl Ernst, “Why ISIS Should Be Called Daesh: Reflections on Religion & Terrorism,” ISLAMICommentary, November 11, 2014. For a compelling argument as to why the use of the label “Islamic” matters, see Shahab Ahmed, What Is Islam? The Importance of Being Islamic (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016), 106-107.

[6] There is copious scholarly literature on the conjunction of apocalypticism and violence in the contemporary world; cf., e.g., the classic account of John R. Hall with Philip D. Schuyler and Sylvaine Trinh, Apocalypse Observed: Religious Movements and Violence in North America, Europe, and Japan (London: Routledge, 2000). For a recent account that takes a broadly historical comparative approach similar to that I have sought to adopt here, see Catherine Wessinger, “Apocalypse and Violence,” in John J. Collins (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Apocalyptic Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 422–440. Wessinger’s treatment attempts to delineate the common discursive and sociological elements that tie together phenomena as diverse as qurʾānic apocalypticism, contemporary jihadism, the Crusades, Anabaptist Münster, Christian Zionism, and the Branch Davidians.

[7] More than one review of Holland’s work accuses him of reducing the religious motivations of European monarchs and churchmen who employed millenarian rhetoric simply to Realpolitik, criticizing his approach to the religious justifications for various political projects around the year 1000 as reductionist. For a particularly transparent example written for a website affiliated with the Christian Dominionist movement, see Lee Duigon, “A Review of The Forge of Christendom,” Chalcedon, n.d. The accusation of reductionism seems to be a common trope levied against studies that expose Christianity’s tendency to be exploited as a political ideology as opposed to approaching the subject with concern for the sincere religious convictions of the individuals involved, but naturally those advocating such an approach to the historiography of European Christendom do not extend such courteous consideration to Muslim jihadists.

Notably, after Holland’s work was published, the thesis that the First Crusade was specifically motivated by belief in an immanent apocalypse was again advanced by Jay Rubenstein in his Armies of Heaven: The First Crusade and the Quest for Apocalypse (New York: Basic Books, 2011); Rubenstein’s approach was widely criticized by historians on the grounds that religious motivations and eschatological or millenarian motivations do not at all amount to the same thing (see, e.g., the review of Jonathan Riley-Smith in Catholic Historical Review 98 (2012): 786–787).

[8] Robert Ferguson has emphasized the emergence of Viking warfare against specifically religious targets such as monasteries—the aspect of Viking raiding that has often been seen as most distinctive of the era, beginning with the attack on Lindisfarne in 793—as a deliberate response to the perceived threat of Frankish campaigns of violence initiated in the 770s that resulted in forced conversions (followed on some occasions by mass executions), imposition of the death penalty for defying Christian ordinances, and destruction of Saxon holy sites; see The Vikings: A History (New York: Viking, 2009), 41–57. Anders Winroth’s recent The Conversion of Scandinavia: Vikings, Merchants, and Missionaries in the Remaking of Northern Europe (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012) underscores the importance of both individual and communal agency in the spread of Christianity in Northern Europe, asserting that the conquest and forced conversion model does not account for the variety of motivations pagans had for accepting the new imperial faith. But the same is, of course, true for the spread of Islam.

[9] See Yitzhak Hen, “Charlemagne’s Jihad,” Viator 37 (2006): 33–51 and the systematic critique of Daniel G. König, “Charlemagne’s ‘Jihād’ Revisited: Debating the Islamic Contribution to an Epochal Change in the History of Christianization,” Medieval Worlds 3 (2016): 3–40; see also the trenchant notes of Jonathan Jarrett posted on his blog, A Corner of Tenth-Century Europe, January 14, 2007 (https://tenthmedieval.wordpress.com/2007/01/14/charlemagnes-jihad/).

[10] This is a polemical claim that has been made against Islam by Christian spokesmen at least since the ninth century, when it was initiated by Arabic-speaking apologists who were well versed in both the religious and historical traditions of Islam: see, e.g., Thomas Sizgorich, “‘Do Prophets Come with a Sword?’ Conquest, Empire, and Historical Narrative in the Early Islamic World,” American Historical Review 112 (2007): 993–2015.

[11] For a convenient recent introduction to this topic, see the essays in C. L. Crouch and Jonathan Stökl (eds.), In the Name of God: The Bible in the Colonial Discourse of Empire (Leiden: Brill, 2014). See also now Erin Runion’s challenging study, The Babylon Complex: Theopolitical Fantasies of War, Sex, and Sovereignty (New York: Fordham University Press, 2014), which directly indicts the biblical foundations of the contemporary American drive to global political and economic domination.

[12] Michael S. Northcott, An Angel Directs the Storm: Apocalyptic Religion & American Empire (London: I. B. Tauris, 2004), 103–133.

[13] Bruce Lincoln, Holy Terrors: Thinking about Religion after September 11 (2nd ed.; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), 19–31.

[14] Brian Tashman, “Bachmann: Rapture Imminent Thanks to Gay Marriage & Obama,” Right Wing Watch, April 20, 2015. The coincidence of an outbreak of right-wing intimations of imminent apocalypse in spring 2015 with growing awareness of the millenarian nature of ISIS ideology at that time is striking. Compare Edward L. Rubin, “Our End-of-the-World Obsession is Killing Us: Climate Denial and the Apocalypse, GOP-Style,” Salon, March 26, 2015, and the Vox interview with Will McCants published a week later, Zack Beauchamp, “ISIS is Really Obsessed with the Apocalypse,” Vox, April 6, 2015. Commentators sometimes cite the dramatic rise in the belief that the End Times are imminent in Muslim societies over the last two decades, but these figures are seldom compared to similar rates of belief about the imminent Rapture among American Christians.

[15] In the first quarter of 2016, with the intensification of the contest for the Republican presidential nomination, it was repeatedly reported that Ted Cruz’s wife, Heidi, openly articulated a theocratic vision for the Cruz presidency to audiences of supporters; other proxies such as Glenn Beck and Cruz’s father, Rafael, an evangelical preacher, reportedly promoted an understanding of Cruz as an ‘anointed king’ divinely appointed to shepherd America through the coming apocalyptic tribulations of the Rapture. See John Fea, “Ted Cruz’s Campaign is Fueled by a Dominionist Vision for America,” Religion News Service, February 4, 2016.

[16] This point is borne out by the evidence: judging by any numbers of standards, the Tea Party-dominated Congress voted in during the 2010 elections was the least productive in American history.

[17] Rubin, “Our End-of-the-World Obsession.” Admittedly, the conviction that an irreversible environmental catastrophe is imminent sometimes appears like a rationalist alternative to apocalypticism. One might thus argue that when confronted with a chaotic world in which crisis is unavoidable, the observer naturally interprets the impending disaster through whichever explanatory mechanism is most appropriate for their worldview, whether scientific or religious. Even doomsday scenarios of a rationalist or scientific nature may draw on symbols traditionally associated with religious narratives (see Gallery Image B).

[18] The number of displaced villagers in Syria may have been as high as 1.5 million. See Henry Fountain, “Researchers Link Syrian Conflict to a Drought Made Worse by Climate Change,” New York Times, March 2, 2015. Admittedly, the drought hypothesis has been challenged, with some analysts arguing that there was no drought at all, and that the crisis was triggered instead by overpopulation and poor economic and agricultural policy (which are, admittedly, factors that are still decidedly environmental, and not ideological or religious, in nature); see, e.g., Roger Andrews, “Drought, Climate, War, Terrorism, and Syria,” Energy Matters, November 24, 2015.

[19] Jeet Heer, “The GOP is the Party of Death,” New Republic, July 19, 2016.

[20] Donald Trump’s call for a ban on all Muslims seeking to enter the United States after the June 2016 Orlando shooting has been most widely discussed given his prominence as the then-presumptive and now current nominee for the Republican presidential ticket. The statements of former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich at the same time, calling for nationwide screening of Muslims and expulsion of any who express a “belief in sharia”—a more pernicious proposal of equally dubious legality, and one that demonstrates a significant misapprehension of Muslim self-conception—received far less attention. See David A. Graham, “Gingrich’s Outrageous Call to Deport All Practicing U.S. Muslims,” The Atlantic, June 15, 2016.

[21] On this, see especially the contribution of Tazeen Ali and Evan Anhorn to this issue.

[22] E.g., Blake Leyerle, “Refuse, Filth, and Excrement in the Homilies of John Chrysostom,” Journal of Late Antiquity 2 (2009): 337–356. Leyerle emphasizes the potency of Chrysostom’s evocation of the horrible material circumstances of urban waste disposal in his time (with which his audience was no doubt directly familiar) as a metaphor for moral corruption and defilement; he thus sought to create a visceral connection in his hearer’s mind between the dubious morality of Jews and pagans and the physical disgust waste and offal would trigger in the viewer.

[23] Trump himself being the centipede par excellence, according to a popular YouTube video that combined a narrative from a nature documentary with footage of Trump debating his opponents: “Despite its impressive length, it’s a nimble navigator … And some can be highly venomous. Just like the tarantula it’s killing, the centipede has two curved hollow fangs, which inject paralyzing venom. The centipede is a predator,” quoted in Almie Rose, “Decoding the Language of Trump Supporters,” Attn.com, March 25, 2016.

[24] E.g., ‘Umm Sumayyah al-Muhājirah,’ “Slave-Girls or Prostitutes?” Dabiq 9 (Sha’ban 1436 [May 2015]), 48. The context is already a hypersexualized one, given the topic at hand; the author contrasts the virile man of the Islamic State who follows divine law and lays claim to that which God has established as his prerogative to enjoy, sexual relations with a slave girl taken as spoils of battle, with the hypocritical ‘quasi-man’ who denounces slavery but slakes his lust with a prostitute, thereby committing the sin of fornication. See Kecia Ali’s contribution to this issue.

[25] Thus, “cuck” is regularly deployed as an epithet for Sanders and his supporters, meant to ridicule such concerns as income inequality and racial justice as effeminate. Transference of the term from Republicans to Democrats is not surprising given the popularity of epithets such as “libtard” and “traitor” for supporters of left-wing causes on social media. Rose, “Decoding the Language,” notes the basic concept underlying “cuck” but neglects (or willfully ignores) the cruder subtexts: a cuckold is a man who is not only the victim of infidelity but actually permits and celebrates his wife’s sexual preference for another man, especially a black (or Hispanic, or Muslim) man, and even supports the offspring of this infidelity as his own child. The nexus of political, social, and racial anxieties embedded in this image is complex, but it fundamentally plays upon the liberal’s supposed attentiveness to racial justice, support for immigration, promotion of political correctness, “appeasement” of radical Islam, and so forth, all of which directly enable the literal or metaphorical penetration of his wife(/country)—and exploitation of himself— by dark foreigners.

[26] In a trenchant essay published not long after the Orlando shootings, Ali Olomi notes that both the ideology of ISIS and that of the Trump campaign rest upon a rhetoric of “toxic masculinity”; both capitalize on a sense not only of disenfranchisement but also emasculation among their followers, caused by different but analogous economic, social, and political problems: “Orlando Shooting and the Tangled History of Jihad and Homosexuality,” Religion Dispatches, June 21, 2016.

[27] Trump made this comment at a rally on August 1, 2016. At the Republican National Convention a few weeks earlier, former candidate for the Republican nomination Ben Carson identified Clinton’s mentor, Saul Alinsky, as Lucifer.

[28] Trump had previously linked Obama and ISIS in his speeches, but it was his insistent assertion that Obama was the founder of ISIS and Clinton the co-founder at a rally in North Carolina on August 10, 2016 that attracted widespread media attention; see Gallery Video A.

[29] Jack Jenkins, “Trumps’ Top Pastor Delivers What May Be the Most Partisan Prayer in Convention History,” ThinkProgress.org, July 19, 2016. Already in April conservative Christian elements were describing Trump as divinely chosen and anointed: see Brian Tashman, “Self-Proclaimed Prophet: God Will Make Donald Trump President and Kill His Enemies,” Right Wing Watch, April 20, 2016.

[30] See the discussion of the mubāhalah to which ISIS leaders summoned the leadership of Jabhat al-Nuṣrah in my contribution to this issue.

[31] Reuven Firestone, Holy War in Judaism: The Fall and Rise of a Controversial Idea (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

[32] For a recent account of militant Zionist agitation against the British Mandate that does not shy from an unequivocal use of the language of “Jewish terrorism,” see Bruce Hoffman, Anonymous Soldiers: The Struggle for Israel, 1917–1947 (New York: Knopf, 2015).

[33] See Gadi Taub, The Settlers and the Struggle over the Meaning of Zionism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 37–64; I owe this reference to Elliot Ratzman.

[34] See Geoffrey Claussen, “Pinḥas, the Quest for Purity, and the Dangers of Tikkun Olam,” in David Birnbaum and Martin S. Cohen (eds.), Tikkun Olam: Judaism, Humanism and Transcendence (New York: New Paradigm Matrix Publishing, 2015), 475–501. I thank Prof. Claussen for providing me with a pre-publication copy of his article. Ginsburgh’s exegesis of the Pinḥas story is perhaps not so exceptional; it is the radical politics to which he applies it that is unusual. Ginsburgh has achieved worldwide notoriety for his blunt statements about the superiority of Jews to other people, even putting this in starkly biological terms, stating that Jewish blood and DNA are inherently worth more than those of gentiles, or that the Torah at least hypothetically authorizes the harvesting of organs from gentiles to save Jews.

[35] For a recent discussion comparing the roots of religious Zionist and Christian Identity violence that specifically addresses the differences between the movements in terms of relative political impact in Israel and the United States, see Arie Perliger, “Comparative Framework for Understanding Jewish and Christian Violent Fundamentalism,” Religions 6 (2015): 1033–1047.

[36] Ironically, in classical Islam the self-sacrificing ethos of volunteer jihadists—many of whom were enthusiastic pietists of an almost monastic type—was apparently appropriated from neighboring Christians; see Thomas Sizgorich, “Sanctified Violence: Monotheist Militancy as the Tie That Bound Christian Rome and Islam,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 77 (2009): 895–921. The activity of these volunteers was often in direct conflict with the attempt of caliphal authorities to professionalize jihad and thus establish an institutional monopoly on violence on the borderlands of Islamic territory, especially those with Byzantium; see Deborah Tor, “Privatized Jihad and Public Order in the Pre-Saljuq Period: The Role of the Mutatawwiʿa,” Iranian Studies 38 (2005): 555–573. Notably, at the time of their ascendance in the global jihadist movement in the 9/11 era, Al-Qa’idah’s rhetorical appeal to recruits strongly emphasized the necessity of defending Muslims from what was represented as a worldwide ‘Crusader-Zionist’ conspiracy to destroy Islam. In contrast, ISIS propaganda represents the establishment of the caliphate as a long-awaited reversal of decline, with a particular implicit appeal to Muslims in Western societies who are often the victims of discrimination, poverty, and social marginalization—less a defensive jihad than a campaign of self-actualization and material improvement. On the specific appeal to alienated and disenfranchised Muslims in the West, see Jessica Stern, “What Does ISIS Really Want Now?”, Lawfare, November 28, 2015.

[37] Sporadic coverage about the American Christian jihadists operating in the theater of war in northern Iraq first appeared in spring 2015 in various newspapers in the Middle East, in both Arabic and English-language editions, and then spread to Western media outlets: see, e.g., Isabel Coles, “Westerners Join Iraqi Christian Militia to Fight Islamic State,” Reuters, February 15, 2015. More detailed reportage from major media outlets began to appear later, e.g., Jen Percy, “At War in the Garden of Eden,” New Republic, August 10, 2015; ibid., “Meet the American Vigilantes Who Are Fighting ISIS,” New York Times, September 30, 2015; Roc Morin, “The Western Volunteers Fighting ISIS,” The Atlantic, January 29, 2016. Some of this coverage has been as unfortunately hyperbolic as treatments of Western Muslims joining ISIS, e.g., Florian Neuhof, “Anti-ISIS Foreign Legion: Ex-Skinheads and Angry White Men Swell Ranks of Christian Militia Fighting Islamic State,” International Business Times, July 13, 2015.

Editor’s Introduction

Context and Comparison in the Age of ISIS

Public scholarship and addressing ISIS as media phenomenon