PDF

Download

Citations

Click and drag then release to select a passage to cite.

Annotations

How to submit annotations to Mizan Journal articles:

your work is published.

Search within

ISIL and the (Im)permissibility of Jihad and Hijrah

Western Muslims between Text and Context

Image

Audio

Video

Chart or Graph

ISIL and the (Im)permissibility of Jihad and Hijrah

Western Muslims between Text and Context

Introduction: Charisma and the Islamic State’s critique of Western society

On June 28, 2014, Abū Muḥammad al-ʿAdnānī, spokesperson for the jihadist organization Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), declared the group’s creation of a global Islamic caliphate.1 This announcement coincided with the first issue of the new state’s propaganda magazine, Dabiq, and the first day of the month-long Muslim festival of Ramadan, a holiday marked by Muslims around the world with fasting and repentance. The Ramadan launch date was meant to be highly symbolic for the declaration of the Islamic State in Dabiq. Mirroring the spiritual invitation of Ramadan, the first issue of Dabiq calls for a return, repentance, and reform to match the earthly restoration of the Islamic caliphate—at once a political, religious, and social answer for a divinely sanctioned pattern of human life and governance.

It is important to bear in mind the close relation of the Islamic State to its media apparatus. While Dabiq is explicitly conceived as a recruitment device, it is not the only manner in which Western Muslims are called to personal and political restoration. By its very nature, the idea of the Islamic State is itself daʿwah—a universal call to all Muslims. Lacking an historical people, established borders, or a cultural heritage, the global caliphate is as much an appeal for an ideal utopian society as it is for a functional political state with boundaries, infrastructure, and the rule of law. The first issue of Dabiq relates the following part of the declaration speech:

O Muslims everywhere, glad tidings to you and expect good. Raise your head high, for today—by Allah’s grace—you have a state and Khilafah, which will return your dignity, mights, rights, and leadership… Therefore, rush O Muslims to your state… O Muslims everywhere, whoever is capable of performing hijrah (emigration) to the Islamic State, then let him do so, because hijrah to the land of Islam is obligatory.2

The language of the speech is clear: the Islamic State is where Muslims truly belong. Indeed, it is the only authentic place of belonging for Muslims, since it alone is able to offer the leadership, dignity, and might that is the true, divinely ordained inheritance of Muslims. In this way, the Islamic State exists in an ideal form—as a charismatic appeal for a potential world. As Max Weber argued, it is not the recognition of a charismatic authority here that validates that authority; rather, true charisma, as Weber conceives it, needs no external validation. Its truth is such that recognition is merely owed to it from the world.3 The failure of some (or even most) to tender this recognition is immaterial to the charismatic claim to authority—it is simply the failing of the world to appreciate the truth, something which then serves to further bolster the tight bonds of the charismatic group. As an engendering idea, as a creative and charismatic impulse, the Islamic State demands recognition—a duty that is left to the rest of the world to fulfill. For non-Muslims, the form of recognition is fear, as evinced in Dabiq’s regular articles devoted to the statements by Western leaders regarding the growing threat posed by the Islamic State. For Muslims, the form of recognition is immigration—to respond to the call to abandon life in the West and join the Islamic State, thus recognizing its claim to legitimacy, its leaders’ authenticity and authority as inheritors (khulafāʾ)The term khālifah, 'caliph,' literally means a successor or inheritor, 'one who comes after'; the plural is khulafāʾ. of prophetic leadership. The obligation of immigration, then, proceeds from a charismatic appeal of recognition and is not hampered in the least by the obverse case: the relative rarity of Muslim immigration to the Islamic State and thus the dearth of recognition. In this ideal form, recognition is a duty; the Islamic State is not dependent upon the support or attitudes of others. Failure to recognize the Islamic State does not imply the failure of the State—rather, it is a failure or fault within ourselves (whether Westerners, Muslims or—most intriguingly—Western Muslims).

Understanding the charismatic nature of Dabiq’s call for immigration is critical to understanding the obligation of hijrah. For Weber, pure charisma seeks to overthrow any established social order, setting itself in diametric opposition to stable, routinized society and economy.4 As Weber argues, the rationalized social and economic order is challenged by charisma precisely because “by its very nature [charisma] is not an ‘institutional’ and permanent structure, but rather, where its ‘pure’ type is at work, it is the very opposite of the institutionally permanent.”5 Yet, as S. N. Eisenstadt has highlighted, in Weber’s thinking, charisma is also foundational to building new institutional orders, so that there is a reciprocal relationship between the charismatic appeal and the institutionalization it seeks to create.6 This is because, as Weber argues, the original basis for the stable social and economic arrangements of society lies in an original charismatic moment that establishes a new precedent for provisioning the needs and demands of the society.7

In its “purest” type, this distribution takes the form of gifts and war booty, which are apportioned according to the pure whim of the charismatic leader. This alternative to the economic organization and provisioning of stable society becomes one of the primary vehicles for the charismatic movement to challenge the stable social order. Yet as the movement stabilizes, the charismatic caprice of the former mode is slowly replaced by increasingly bureaucratic and routinized forms, which seek to provision the needs and demands of the society members in a manner that is more organized and predictable over time. Yet the initial charismatic impulse lies at the foundation of new institutions and social arrangements. As Eisenstadt argues elsewhere, institutions retain the capacity to return in part to their original charismatic impulse, as new entrepreneurial figures seek to bring reform and renovation to ossified and stagnant social institutions.8

In this way, just as oil revenues fund the Islamic State’s administration, charisma finances the very construction and operation of the command to immigrate, and sets the claims of the Islamic State into a certain relationship with the West. As a charismatic regime, the Islamic State is imagined to be the very antithesis of Western stability and bureaucracy, whose routinization and standardization stifle the creative impulse that is essential to the charismatic worldview. In order to achieve the utopian vision of the Islamic State, the call to immigrate demands complete abandonment of the West—it is either Us or Them, either the revolutionary charismatic calling or the ossified social structure of the West. To immigrate is not to move from one country to another. It is to abandon a habituated social order in favor of the limitless potential of a conceptual frontier.

It is in this context that the third issue of Dabiq constructs the Islamic State’s claim of immigration over Western Muslims. The issue’s feature article, entitled “Hijrah from Hypocrisy to Sincerity,” lays out the psycho-social realities of immigration.9 Here, the author seeks to address the putative barriers that might impede young (and pronominally male) Western Muslims from leaving the West, including the relative safety, economic security, and educational opportunities represented by Western life. In so doing, the author presents an idea of the West in contrast with an idea of the Islamic State, suggesting what it might mean to belong to either.

In this way, the personal safety of life in the West is neither emulated nor ignored in the Islamic State, but rather turned on its head, so that the promise of pure death in martyrdom is the celebrated opportunity of the charismatic regime. This immediate and intimate access to the charismatic world is essential to the Islamic State’s claims to subvert the rigid, impersonal, and bureaucratic life of the West. Similar themes of immediacy are carried through the article’s critique of the “modern day slavery of employment,” which is contrasted with the right of war booty (including enslavement) as the prophetic inheritance of all Muslims.10 Again, the economic security of Western society is not denied; rather, the purity of the one who “eats from… his sword” is extolled, contrasting the impersonal wage-labor of Western economies with the unique and personalized rewards of the charismatic economy.11 Finally, the article does not deny the opportunities for education—even Islamic education—in the West, but instead invites Western Muslims to apply their knowledge in the building of a new world.

Each case celebrates the experience of immediacy allegedly found in life under the Islamic State—an ideal place where one breaks from the rigid, impersonal, and hierarchical life of the West—without denying the purported (if equally idealized) experience of life in Western society. As commentators standing outside of that social order, the authors of Dabiq are nevertheless responding to it, which can be seen in the very construction of the obligation for hijrah. While invoking Islamic texts and narratives, the charismatic call and authority of the Islamic State articulated in Dabiq is thus intimately connected with Western society as it is imagined by the authors, who then articulate their Islamic alternative in direct relation to the West.

Performing American Islam: The “Open Letter to Al-Baghdadi”

In late September of 2014, in a speech addressed to the UN General Assembly, Barack Obama called upon Muslims all over the world to “explicitly, forcefully and consistently reject the ideology of organizations like al-Qaeda and ISIL.”12 Around the same time, in an interview with CNN’s Christiane Amanpour, John Kerry also asserted that Muslims worldwide would be required to “reclaim Islam” in the greater campaign against ISIL.13 Elsewhere both Obama and Kerry explicitly attempted to attenuate, at least verbally, the relationship between Islam and ISIL. For example in his official statement on ISIL, Obama, channeling the same sentiments expressed by George Bush following the September 11 attacks, insisted that the perpetrators of violence were “not ‘Islamic’” and even remarked that the majority of ISIL targets have been Muslim.14 Much to the surprise and dismay of many commentators, Kerry went a step further and insisted on calling ISIL by the pejorative Arabic term “Daʿesh”A derogatory name for ISIS/ISIL derived from rendering their Arabic name al-dawlah al-islāmiyyah fī'l-ʿirāq wa'l-shām (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) as an acronym, with its insulting connotations variously explained. on the basis that the group’s actions “are an insult to Islam” and therefore should not be called Islamic.15

At best, these efforts by American political leadership to make clear a distinction between Islam and ISIL are well-intentioned, and presumably meant to assist Muslim communities across the globe who might be unfairly associated with violent groups such as ISIL. However, we argue that the sharp imperatives laid out by Obama and Kerry for Muslim communities worldwide to denounce violence enacted by ISIL actually reinforce associations between “Islam” and ISIL in public perception in the United States. By requiring all Muslims to disavow the violence of groups like ISIL, there is an implicit notion that, in essence, there is indeed a link between extremist groups and Muslims unless otherwise noted. Moreover, when the most powerful American political figures construct such a linkage between all Muslims and ISIL, there are significant implications for Muslims in the West. For American Muslims in particular, the seemingly innocuous imperatives made by Obama and Kerry signify that being a part of the American public discourse requires the adoption of certain rules and parameters that have been dictated for them. For example, public discussions over ISIL are restricted to what Islam and the Qurʾān do or do not say about topics such as violence, jihad, slavery, and women’s status. This in turn means that American Muslim leaders can only respond on those same terms. They are required to engage with questions of religious interpretation rather than discuss foreign policy, free market capitalism, and the marginalization of Muslims in the West, all factors that inform the current situation in Iraq and Syria.16

Obama and Kerry represent the hegemonic discourse that establishes what issues are at stake and which questions are of significance. In this context, Western concerns about each and every act of violence perpetrated by Muslims are almost always dictated in religious terms. What is expected of American Muslim leaders, then, is to conform to these expectations by providing a religious response to ISIL. By providing Islamic counter-arguments to the kinds of claims articulated in ISIL publications such as Dabiq, as mentioned earlier, and restricting the discussion solely to matters of religion, American Muslims are forced to accept the rules of the debate. In other words, American Muslims are compelled to acquiesce to a discourse that not only emphasizes religion and theology but also effaces socio-political and material conditions as viable causal factors to understanding the phenomenon of ISIL.

Furthermore, in performing the role that is expected of them, we argue that American Muslims are actually participating in another debate entirely, namely about the legitimacy of Muslim belonging in the United States. Here it is helpful to draw on David Scott’s concept of the “problem space” which is defined as

… an ensemble of questions and answers around which a horizon of identifiable stakes (conceptual as well as ideological-political stakes) hangs. That is to say, what defines this discursive context are not only the particular problems that get posed as problems as such (the problem of “race,” say), but the particular questions that seem worth asking and the kinds of answers that seem worth having. Notice, then, that a problem-space is very much a context of dispute, a context of rival views, a context, if you like, of knowledge and power. But from within the terms of any given problem-space what is in dispute, what the argument is effectively about, is not itself being argued over.17

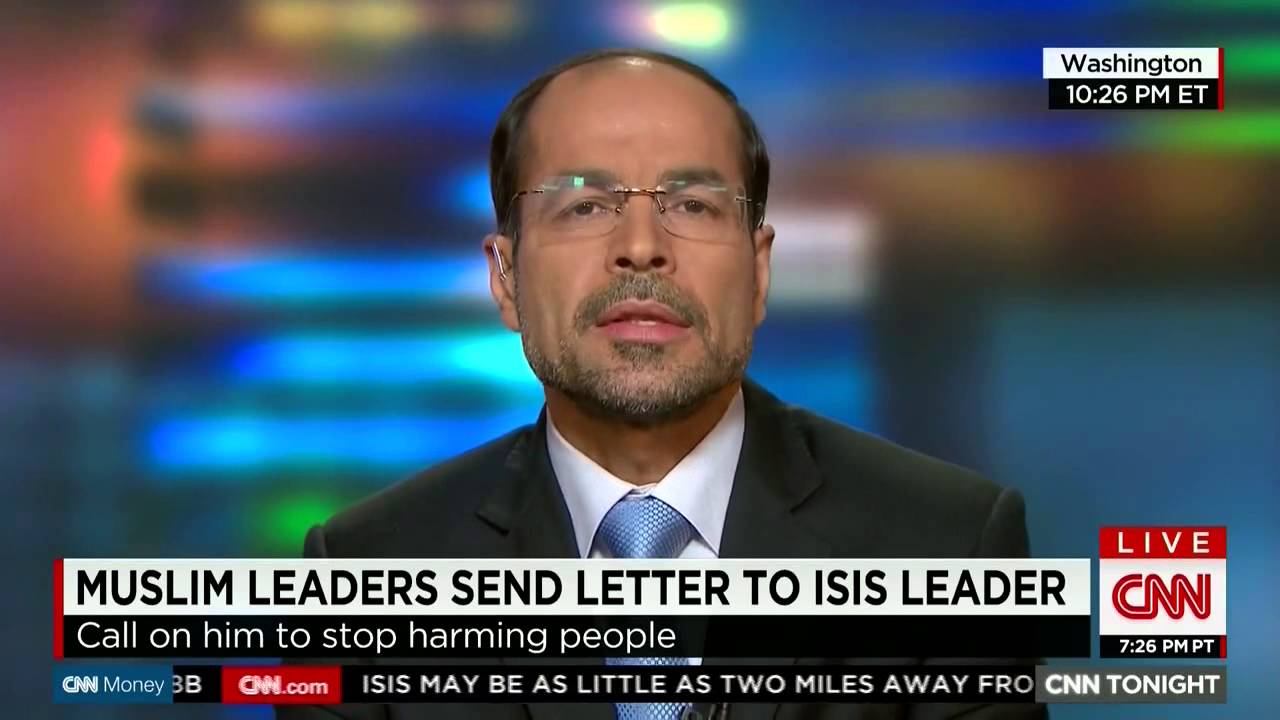

According to Scott, a “problem space” comprises a specific set of issues that make up the framework of a given debate. This framework is defined by particular questions and answers that are dependent upon various networks of power. However, within this framework of questions, the real topic at hand is not itself acknowledged in explicit terms. For instance, the structure of the American debates over ISIL is determined by the hegemonic power of politicians and mainstream media. In this case, figures such as Obama, Kerry, and even CNN’s Don Lemon—who earnestly inquired if American Muslim human rights lawyer Arsalan Iftikhar supported ISIL (see Gallery Video A)—set the terms of the debate from their positions of power.18 Specifically, they require that Muslims respond to queries on ISIL through the lens of religious commitments and affiliation.

Obama and Kerry both singlehandedly put the burden of responsibility on all Muslims to condemn what is considered “Islamic extremism” as a necessary component of overcoming this complex global phenomenon. Accordingly, in the televised interview with Iftikhar referenced above, Lemon insistently expected him to explicitly articulate his personal position on ISIL. It was not sufficient that Iftikhar had spent the previous five minutes arguing that all Muslims should not be personally held responsible for terror attacks, in the same way that Christian leaders are not asked to be accountable for acts of violence perpetrated by those with a Christian background. Nor did Iftikhar’s background as an international human rights attorney qualify him to be perceived as someone who would naturally be appalled at the actions of a group such as ISIL. Iftikhar’s responses were not considered acceptable precisely because they did not fall within the parameters of the debate. These are clear examples of Scott’s questions and answers “that seem worth asking… and worth having.”19 The only questions and answers that are deemed worthwhile in this context are whether or not all Muslims (and in particular, American Muslims), as people who purportedly share a faith with violent groups, agree with the ideology of ISIL. Furthermore, an endorsement of ISIL is apparently the default stance of all Muslims unless explicit and public apologies and/or condemnations are made (and sometimes despite this). Applying David Scott’s concept of the “problem space” to American debates about ISIL, then, we argue that these debates are not really about the permissibility of jihad and emigration in Islam, nor are they centered on the qurʾānic stance on violence or warfare. Rather, these conversations mask the real issue at stake, which is whether or not Muslims can ever truly belong in North America.

This renders the Muslim role in the West performative, in that it functions as a way to lay claim to American belonging. This role is evidenced through what is popularly known as the “Open Letter to Al-Baghdadi” issued by over 120 prominent Muslim scholars worldwide, including representatives from key North American Islamic institutions such as CAIR, ISNA (Islamic Society of North America) and Fiqh Council of North America, Zaytuna College, ADAMS Center in DC, as well as a few Islamic Studies professors from US institutions. The letter was released on September 24, 2014 and spans seventeen pages of text, with versions available in Arabic, English, French, Turkish, and Persian.20

The letter is intended by its authors to be a dense and meticulous refutation of the ideology of ISIL. It draws exclusively, albeit superficially, on the classical legal tradition, ḥadīth, and Qurʾān in order to delegitimize the Islamic State. The first sections of the letter draw heavily on classical legal tradition (specifically that of the Shafi’ite school) in order to establish scholarly privilege in scriptural interpretation. As such the letter and its signatories emphasize knowledge of uṣūl al-fiqh (exegesis) and a thorough command of Arabic as qualifications needed to quote the Qurʾān to advance a particular position. This is in contrast to the preferred interpretative method of ISIL as seen in Dabiq, wherein any reader can pick up the text and interpret verses in isolation. To this point, the Open Letter asserts that “it is not permissible to quote a verse, or part of a verse, without thoroughly considering and comprehending everything that the Qurʾān and Hadith relate about that point.”21

According to Nihad Awad of CAIR, who presented the letter in a press conference in Washington, DC, the letter was meant to dissuade potential recruits from emigrating for the purposes of jihad. Awad further states that the letter “is not meant for a liberal audience” and that some mainstream Muslims may not understand it either.22 However, we contend that the outwardly complex legal argumentation renders it inaccessible to any potential ISIL recruits as well. Furthermore, the inaccessibility of the letter in our view is a part of the American Muslim performance that emphasizes religious and theological argumentation at the expense of a discussion of socio-political context surrounding the rise of ISIL. The most accessible part of the letter is its executive summary, which comprises twenty-four bullet points, each corresponding to a longer section within the body of the letter. The presence of this executive summary, we argue, signals that the very format of the Open Letter itself appears to be intended for a Western, non-Muslim public. Executive summaries are a standard feature of business and journalistic reports, and not typically utilized in either traditional or contemporary Islamic legal texts.

Interestingly, twenty-two out of these twenty-four points incorporate the statement “it is forbidden in Islam” or “it is permissible in Islam.” For example, point eight reads: “Jihad in Islam is defensive war. It is not permissible without the right cause, the right purpose, and without the right rules of conduct.”23 However, John Kelsay demonstrates the complex ways in which “right conduct” in jihad can be accommodated in multiple contexts, thereby extending the purview of “defensive war” and also allowing for the possibility of offensive jihad.24

Furthermore, we argue here that these definitive statements treat “Islam” as a monolithic entity with a singular stance on various issues, which in many ways is the very same critique that the letter directs towards ISIL ideologues. In fact, the letter’s usage of multiple singular statements on Islam contradicts point four that refers to the allowance for differences of legal opinion within the classical tradition. The signatories of the letter argue for the legal pluralism of Islam, while simultaneously claiming that ISIL is unequivocally “un-Islamic.” These contradictory statements indicate that despite the appearance of complex legal reasoning, the Open Letter only superficially reflects the classical tradition.

Moreover, despite Awad’s assertions to the contrary, the “Open Letter to Al-Baghdadi” does not, in fact, engage deeply with classical religious texts and scholars. It may appear this way to the casual observer because it is laden with technical language and vague invocations of prominent classical scholars. However, the outward complexity and inaccessibility of the letter to Western audiences do not suffice to render it an accurate portrayal of the classical legal tradition. Here, the Open Letter actually mirrors the superficial rhetoric employed by ISIL in Dabiq, which is also laden with references to classical scholars.

For example, in the second point of the letter regarding the centrality of Arabic linguistic expertise, the authors of the letter contend that mastery of Arabic grammar, syntax, and morphology is required to understand legal theory. The letter then makes a distinction between khilāfah and istikhlāf, in order to argue that the latter term signifies settling in a particular place, rather than rulership. As such, ʿAdnānī’s failure to distinguish between the two terms in this same way in his declaration of the ISIL caliphate is cited as a grave linguistic error that stems from his lack of command of Arabic.25 The letter thus dismisses ʿAdnānī’s declaration that the caliphate is a reference to the qurʾānic injunction of “God’s promise” as an inaccurate interpretation of the Qurʾān. However, in our view, this dismissal does not actively engage with the fact that ʿAdnānī is a native Arabic speaker of Syrian background, and according to Shaykh Abū Turkī b. Mubarak al-Binʿalī, one of the leading authorities cited by ISIL for its legal rulings, he is indeed learned in the religious sciences. According to a statement published online by Shaykh Binʿalī, ʿAdnānī memorized the Qurʾān at a young age and went on to study tafsīr, ḥadīth, and fiqh.26 On this basis, ʿAdnānī’s credentials would, in fact, appear to fulfill the scholarly prerequisites as specified in the letter to engage in the interpretative exercise of ijtihād.

Furthermore, multiple sections of the letter draw on Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad b. Idrīs al-Shāfiʿī’s (d. 820) teachings in a selective manner when it bolsters particular claims against the legitimacy of ISIL. It appears to gloss over and omit selections of Shafi’ite teachings that might, in fact, support ISIL’s claims. For example, drawing on David Vishanoff, Kecia Ali describes “linguistic ambiguity” as a key element of Shafi’ite legal theory. Ali and Vishanoff demonstrate that Shafi’ite hermeneutics allow jurists to interpret texts in multiple ways, even while championing a singular interpretation as objectively true in accordance to divine intent.27 This indicates that the very same Shafi’ite hermeneutic that is advanced in various parts of the Open Letter could conceivably be used to advance certain aspects of ISIL ideology.

The appearance of complex legal reasoning in the letter constructs an authentic neo-traditional style of argumentation by drawing on the classical sources, which by necessity is lengthy and somewhat inaccessible. This very inaccessibility, however, appears deliberate, because it ultimately serves to persuade non-Muslim audiences of its authenticity. As Awad said in the press conference, “the letter will still sound alien to most Americans… it is using heavy classical religious texts and classical religious scholars.”28 Yet, the letter publicly demonstrates moderate Western Muslims actively taking control of their tradition’s narrative, and performing the role that is expected of them by figures such as Obama and Kerry. This performative aspect of the letter is further played out on the Internet. The letter has its own website where users are invited to add their signature to the letter, and then publish their endorsement on Twitter and Facebook. This provides a way for Western Muslims to publicly condemn ISIL through their personal social media accounts with the authoritative backing of respected religious scholars. This highlights that public condemnation of ISIL is the requirement established for Muslims by the hegemonic discourse.

Awad further contends that the letter “is not meant for a liberal audience,” but rather for those might be attracted to ISIL recruitment.29 However, we argue that this Open Letter is indeed meant for a Western liberal audience. Most of the points in the executive summary appear designed to allay specific Western anxieties about ISIL. For example, point seven clearly states, “it is forbidden in Islam to kill emissaries, ambassadors, and diplomats; hence it is forbidden to kill journalists and aid workers.”30 This is in direct reference to the killings of the two American journalists, James Foley and Stephen Sotloff, and British aid worker David Haines, who are all mentioned in the letter by name. Foley, Sotloff, and Haines were hostages of the Islamic State who were all beheaded only a few weeks prior to the release of the letter, and so at the forefront of public consciousness. Their executions are described as “unquestionably forbidden (haraam).”31 The inclusion of these British and American names as emissaries serves as further evidence that this letter is aimed towards a non-Muslim Western audience, given that there was no mention of the seventeen Iraqi journalists who had also been killed by ISIL in preceding months.

In highlighting some of the internal contradictions present in the “Open Letter to Al-Baghdadi,” it is not our intention to suggest that the authors and signatories of the letter are disingenuous in any way. Rather, we seek to emphasize that the superficiality with which the letter engages with classical religious argumentation in its refuting of ISIL confirms its primary role in another debate, that is, the issue of American Muslim belonging. The chief purpose of the letter, in our view, is to argue for the legitimacy of Muslims in American society. While the authors of the letter may not necessarily be conscious of this masked debate, they are nonetheless actors who partake in this discourse of belonging. The rules of the hegemonic discourse as articulated by Obama and Kerry are such that any discussion of ISIL by Muslim leaders must necessarily address theology. American Muslim debates on ISIL and the demand that all Muslims must publicly condemn the Islamic State clearly demonstrate that Muslims must struggle to claim a place in American society that they currently do not have. We argue, then, that Western Muslim debates over the (im)permissibility of jihad and emigration to join ISIL are less about rival interpretations of Muslim legal texts and scripture, and rather speak more to the discourse of Muslim belonging in North America.

Challenging the Islamic State: Muslim institution building in the West

Many key voices in American politics have responded to the ideological challenges of the Islamic State by emphasizing the role and responsibility of the Western Muslim community as the vanguard of an anti-Islamic State religious discourse. While some politicians have made efforts to draw public attention to the diversity of Muslim belief on issues of violence and terrorism, this strategy also runs the risk of alienating Muslims in the West, who are told that the expression of a vocal stance on the Islamic State is the criterion for their acceptance in the West (just as the Islamic State claims their hostile posture towards Western states and society is the criterion for their acceptance under Islam). Such strategies have done tremendous damage to the establishment of social trust by making narratives of conflict essential to narratives of belonging.

Given the charismatic claims of the Islamic State and the awkward social positioning of American Muslims, what might be a more constructive approach to promoting both civic participation and ownership of American Islam? For Weber, the charismatic orientation towards society arises out of “times of psychic, physical, economic, ethical, religious [or] political distress.” 32 While Weber himself did not elaborate a great deal about these conditions, Eisenstadt has argued that this occurs when the rigidity of the prior social order fails to provide a sense of shared meaning and belonging to its members. Yet charisma is not only found in these moments of catastrophe; rather, as Eisenstadt has suggested, charisma plays a vital and productive role in much more mundane situations as well, particularly in reforming and transforming social institutions. For Eisenstadt, the original charismatic drive of the institution—which first led to its formation—provides later institutional actors with the resources to remap powerful symbols and reorient the institution to address new challenges in ever-changing social conditions. In this way, robust institutions are both the counterweight to claims of authority derived from pure charisma, as well as the filter through which charisma may be channeled into vital and sustaining social work. In the struggle to determine who speaks for Islam, then, Western Muslim institutions are ideally situated to contest Islamic State narratives primarily because they have recourse to the same charismatic potential.33

Productive examples might be drawn from Germany and the Netherlands, where the state has engaged with and even supported local Islamic institutions, resulting in greater access to civic and political participation for Muslim minority communities. As Ahmet Yükleyen has argued, these institutions have played a central role in the process of integrating Muslim immigrant communities. Such organizations, Yükleyen argues, vitally serve to “negotiate between the social and religious needs of Muslims, on the one hand, and the social, political, and legal context of Europe, on the other.”34 In this way, the ability of German and Dutch Muslim communities to engage the state is largely determined by the successful establishment of the communities’ institutions. Comparing Moroccan and Turkish communities in the Netherlands, Yükleyen notes that

Despite their similar numbers, Turks have 206 mosques, whereas Moroccans have 92. Turkish mosques provide social and religious services, whereas Moroccan mosques are limited to ritualistic services. A higher level of religious institutionalization and functional diversity provides Turkish Muslims with greater negotiating power with the state.35

Due to a number of factors, including the relative degree of involvement of the Turkish and Moroccan governments, Turkish Muslim institutions have been much more successful than Moroccan institutions, which has resulted in different access to political and civic engagement in the Netherlands. In Europe, such institutions incorporate the dual functions of providing transparency for state regulation as well as meeting the needs of the religious community.36 Moreover, these institutions are critical sites for remapping Islamic symbols to address new challenges and social change. As more Muslim refugees arrive in Europe, such institutions (and models of state-supported institutionalization) could provide vital resources for new communities, even as European governments increasingly put counter-productive pressure on these institutions to serve as vehicles for integration, assimilation, and state security policies.

While occupying a medial position between the demands of state regulation and the needs of the faith community, Turkish Muslim organizations in the Netherlands compete in a marketplace of religious institutions where they must leverage both the civic participation of the community as well as government support to come out on top. They navigate the political terrain and engage their communities in a way that is largely transparent, public, and pro-integration. By allowing dual citizenship and accommodating participation on the political stage, the Dutch program has produced a Muslim discourse on integration that is more participatory and cooperative. These Muslim groups, left to define their goals and participation in society, have formed into political-centrist organizations to take the most advantage of the democratic system. To build relationships between individual Muslim groups and political parties, such organizations have necessarily adopted a more inclusive Islamic message.

An alternative picture can be drawn from Germany, which also has a long-established Turkish Muslim population. While many of the same Turkish Muslim organizations exist in Germany, the state has adopted a very different approach to Muslim institution building—one that has been much less proactive in comparison to the broadly multiculturalist approach of the Dutch. The government’s hesitation in supporting these organizations in Germany in part reflects the Turkish state’s involvement with the expatriate institutions. Many imam posts in German mosques are temporary positions filled by preachers trained and assigned by Diyanet, the Turkish ministry of religion. The centrally produced and disseminated Friday sermons (hutbe) of the visiting imams, as well as the apparent ambivalence of Diyanet towards the integration of Turkish Muslims into European society, has spurred a deep current of suspicion between the German state and the Diyanet-associated mosques and organizations.

At other times, the German state has taken steps to incorporate Muslim organizations into the political process, for instance through the annual Deutsche Islam Konferenz (German Islam Conference) initiated by former Minister of the Interior Wolfgang Schäuble in 2006. The goal of the conference was to bring together German politicians and representatives of the Muslim community in Germany to discussion matters of integration and accommodation. Yet the state’s interest in the forum languished amid complaints that the conference had failed to produce a reasonably representative voice for Germany’s diverse Muslim population. In addition to demanding clearer accountability and consensus, the state also expressed concerns over the inclusion of Muslim groups that it had labeled as Islamist, including the same organization— Milli Görüş—which had made long strides in integration and institutionalization in the neighboring Netherlands. Eventually, the state moved to block the participation of Milli Görüş and others in the Islam Conference, which in turn frustrated other participating organizations and undermined the promising potential of the conference. By 2009, Schäuble had declared that “multiculturalism is not a solution” to integration in Germany.37

The process of institutionalization is an important counterbalance to the claims of charismatic movements like the Islamic State. For Weber, although charisma breaks down the rules and order of society, it is also the origin of social institutions—the concretion of creative social visions first articulated in the charismatic annihilation of previous social orders. For charisma to survive the death of the charismatic founder, it must institutionalize into permanent organizations and structures, which then mediate and delimit the original charismatic vision. Yet the institutionalization of charisma never does away with the generative openness that lies at its core. Rather, as Eisenstadt has highlighted, there is a constant interplay between the “charismatic potentialities” of a social vision and the more organizational forms and processes that regulate and maintain it.38 Charisma remains an important feature of the institution that lends it authority, while paradoxically allowing for change and transformation from within.

Despite the paranoia that often surrounds Muslim spaces in the West—frequently conceptualized as backwards, conservative, and dangerous in Western media—native Islamic institutions provide the most grounded challenge to the Islamic State’s charismatic claims.39 Not only do local Islamic institutions furnish Western Muslims with an alternative model of religious integration and habitation that can compete with the narratives of the Islamic State, but more importantly, they provide a space for participation and social engagement that more directly serves Western Muslims’ need for social stability, cohesiveness, and community boundaries. Institutions provide access to resources and opportunities for their members that can be leveraged for advantage and gain. The nature of these advantages is determined in part by countless historical influences that shape the structurization of the charismatic institution. On the one hand, as the charismatic authority finds institutionalized, routinized expression, it must relocate itself within the existing society. On the other hand, in addition to these historical factors, the positive opportunities of the institution are also shaped by the original creative ethos—the creative vision of authority and society as it emerged from the pure potential of charismatic authority.40

In all this, we must be careful not to read Islamic State claims with a naive understanding of the category of religion. It would be a mistake to dismiss the claims of the Islamic State as merely a thin pretense for political and material gain. One has to look no further than Weber’s formative study of the emergence of capitalism in Northern Europe under the influence of Calvinist ethical and soteriological doctrine to understand that formal distinctions between religious and economic activity are not always possible.41 At the same time, the recent Atlantic article “What ISIS Really Wants” or the New York Times article “ISIS Enshrines a Theology of Rape” run the risk of reducing the vast corpus of Islamic legal and exegetical texts to a selectively distorted formulation of “what Islam has to say about the matter,” whether that matter is war, rape, or emigration.42 Any such formulation would necessarily decontextualize positive statements by historical interpreters, while simultaneously ignoring the prolific literature that complicates or contradicts those statements. More importantly, as Kecia Ali has noted, such an approach turns a blind eye to the historical, social, and political realities of violence, and the interstitial spaces that breach and connect them.43 Without carefully attending to the different ways in which violent actions and rhetoric emerge, including the social contexts within which violence is articulated or enacted, we jeopardize our opportunity to better understand it, as well as other forms of violence that were previously treated as sui generis.

About the authors

Tazeen Ali and Evan Anhorn are doctoral students in the Department of Religious Studies at Boston University.

Notes

All digital content cited in this article was accessed on or before September 21, 2016.

[1] The authors presented an earlier version of this paper jointly at the conference Global Halal at Michigan State University in February 2015.

[2] “Khilafah Declared,” Dabiq 1 (Ramaḍān 1435 [June-July 2014]): 7–11, 7.

[3] Max Weber, “The Sociology of Charismatic Authority,” in On Charisma and Institution Building, ed. S. N. Eisenstadt (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1968), 18–27, 20.

[4] This article draws from Weber’s later essays on charisma, originally edited and translated by H. H. Gerth and C. Wright in From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1946), and later compiled in the 1968 volume edited by S. N. Eisenstadt cited above. Later in this article, we attempt to draw Weber’s analysis of charisma and institutionalization into the theoretical discussion of S. N. Eisenstadt. Where this is the case, we have endeavored to make the transition between Weber and Eisenstadt’s theories as clear as possible.

[5] Weber, “The Sociology of Charismatic Authority,” 22.

[6] S. N. Eisenstadt, “Introduction,” in Weber, On Charisma and Institution Building, ed. Eisenstadt, liii.

[7] Weber, “Sociology of Charismatic Authority,” 18.

[8] S. N. Eisenstadt, Power, Trust, and Meaning: Essays in Sociological Theory and Analysis (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1995), 188–190.

[9] “Hijrah from Hypocrisy to Sincerity,” Dabiq 3 (Shawwāl 1435 [July-August 2014]): 25–34.

[10] Ibid., 29.

[11] Ibid.

[12] “Remarks By President Obama In Address To The United Nations General Assembly,” The White House Office of the Press Secretary, September 24, 2014.

[13] “Interview With Christiane Amanpour Of CNN,” U.S. Department of State Diplomacy in Action interview transcript, September 24, 2014.

[14] “Statement by the President on ISIL,” The White House Office of the Press Secretary, September 10, 2014.

[15] Shadi Hamid and William McCants, “John Kerry Won’t Call The Islamic State By Its Name Anymore. Why That’s Not A Good Idea,” The Brookings Institution, December 29, 2014.

[16] For more on this discussion, see Mahmood Mamdani, Good Muslim Bad Muslim: America, the Cold War, and the Roots of Terror (New York: Doubleday, 2004). Mamdani discusses how in the wake of 9/11 and the War on Terror, a “good” Muslim was/is one who was secular and Westernized. We argue that American debates over ISIL and Muslim belonging in the United States are a different manifestation of the same trend: US discourse about American Muslims continues to define the boundaries of acceptable and unacceptable forms of religiosity.

[17] David Scott, Conscripts of Modernity: The Tragedy of Colonial Enlightenment (Durham: Duke University Press, 2004), 4.

[18] David Edwards, “‘Do You Support ISIS?’: CNN’S Don Lemon Stuns Muslim Human Rights Attorney,” Rawstory.Com, 2015.

[19] Scott, 4.

[20] “Open Letter to Dr. Ibrahim Awwad al-Badri, alias ‘Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi,’ and to the Fighters and Followers of the Self-Declared ‘Islamic State,’” Council on American-Islamic Relations and Fiqh Council of North America, September 19, 2014. The document is available in a number of different formats and translated into several languages at www.lettertobaghdadi.com. Here we will refer to the page numbers of the downloadable PDF of the English version.

[21] “Open Letter to Al-Baghdadi,” 3.

[22] Lauren Markoe, “Muslim Scholars Release Open Letter to Islamic State Meticulously Blasting its Ideology,” Huffington Post, September 24, 2014. Interviewed on CNN on September 19, Awad promoted the letter as presenting a commonsense argument, stating that in it “we told them what every Muslim would tell them” (see Gallery Video B).

[23] Ibid., 1.

[24] John Kelsay, Arguing the Just War in Islam (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007).

[25] “Open Letter to Al-Baghdadi,” 3–4.

[26] Shaykh Abū Turkī b. Mubarak al-Binʿalī, “A Biography Of IS Spokesman Abu Muhammad Al-Adnani As-Shami,” Pietervanostaeyen, November 1, 2014 ). On Binʿalī himself, see Cole Bunzel, “The Caliphate’s Scholar-in-Arms,” Jihadica, July 9, 2014.

[27] Kecia Ali, Imam Shafi’i: Scholar and Saint (Oxford: One World, 2011), 67.

[28] Markoe, “Muslim Scholars Release Open Letter to Islamic State.”

[29] Ibid.

[30] “Open Letter to Al-Baghdadi,” 1.

[31] Ibid., 6.

[32] Weber, “Sociology of Charismatic Authority,” 18.

[33] Weber recognized three ideal types of legitimate authority, of which charisma was only one type. Yet Weber also recognized an interplay between different forms of authority. Following the death of the leader, charismatic authority undergoes a necessary process of routinization whereby the teachings of the leader become standardized and codified, leading to the emergence of a more rational, bureaucratic, and institutionalized form of legitimate authority. Likewise, the anti-structural tendencies of charisma continue to play a key role in the life of the institution, providing generative grounds for reform and renewal. As Weber is careful to point out, these are modes of “pure” authority that are much more complicated and interwoven in historical practice. See Weber, On Charisma and Institution Building, ed. Eisenstadt, 46–65.

[34] Ahmet Yükleyen, Localizing Islam in Europe: Turkish Islamic Communities in Germany and the Netherlands (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2012), 42.

[35] Ibid., 42.

[36] As Yükleyen has argued, some European Muslim institutions even compete with one another by leveraging their congregations to become more involved in social and political processes; Yükleyen, Localizing Islam, 204–211.

[37] Rafaela von Bredow and Katrin Leger, “Schäuble zum Integrationsdebakel: ‘Multikulti ist keine Lösung,’” Spiegel Online, January 25, 2012.

[38] S. N. Eisenstadt, “Charisma and Institutionalization in the Political Sphere,” in Weber, On Charisma and Institution Building, ed. Eisenstadt, 45.

[39] Ebrahim Moosa, What Is a Madrasa? (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2015).

[40] In actuality, both of these are historically contingent, cultural criteria. It is partly this realization that led Eisenstadt to his critique of the theory of social differentiation, his understanding of multiple modernities, and his advocacy of a comparative-civilizational approach to the study of social-structural evolution. See S. N. Eisenstadt, Comparative Civilizations and Multiple Modernities (2 vols.; Leiden: Brill, 2003).

[41] Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, trans. Stephen Kalberg (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

[42] Graeme Wood, “What ISIS Really Wants,” The Atlantic, March 2015; Rukmini Callimachi, “ISIS Enshrines a Theology of Rape,” The New York Times, August 13, 2015.

[43] Kecia Ali, “The Truth About Islam and Sex Slavery History Is More Complicated Than You Think,” The Huffington Post, August 19, 2015.

ISIL and the (Im)permissibility of Jihad and Hijrah

Western Muslims between Text and Context

Introduction: Charisma and the Islamic State’s critique of Western society

On June 28, 2014, Abū Muḥammad al-ʿAdnānī, spokesperson for the jihadist organization Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), declared the group’s creation of a global Islamic caliphate.1 This announcement coincided with the first issue of the new state’s propaganda magazine, Dabiq, and the first day of the month-long Muslim festival of Ramadan, a holiday marked by Muslims around the world with fasting and repentance. The Ramadan launch date was meant to be highly symbolic for the declaration of the Islamic State in Dabiq. Mirroring the spiritual invitation of Ramadan, the first issue of Dabiq calls for a return, repentance, and reform to match the earthly restoration of the Islamic caliphate—at once a political, religious, and social answer for a divinely sanctioned pattern of human life and governance.

It is important to bear in mind the close relation of the Islamic State to its media apparatus. While Dabiq is explicitly conceived as a recruitment device, it is not the only manner in which Western Muslims are called to personal and political restoration. By its very nature, the idea of the Islamic State is itself daʿwah—a universal call to all Muslims. Lacking an historical people, established borders, or a cultural heritage, the global caliphate is as much an appeal for an ideal utopian society as it is for a functional political state with boundaries, infrastructure, and the rule of law. The first issue of Dabiq relates the following part of the declaration speech:

O Muslims everywhere, glad tidings to you and expect good. Raise your head high, for today—by Allah’s grace—you have a state and Khilafah, which will return your dignity, mights, rights, and leadership… Therefore, rush O Muslims to your state… O Muslims everywhere, whoever is capable of performing hijrah (emigration) to the Islamic State, then let him do so, because hijrah to the land of Islam is obligatory.2

The language of the speech is clear: the Islamic State is where Muslims truly belong. Indeed, it is the only authentic place of belonging for Muslims, since it alone is able to offer the leadership, dignity, and might that is the true, divinely ordained inheritance of Muslims. In this way, the Islamic State exists in an ideal form—as a charismatic appeal for a potential world. As Max Weber argued, it is not the recognition of a charismatic authority here that validates that authority; rather, true charisma, as Weber conceives it, needs no external validation. Its truth is such that recognition is merely owed to it from the world.3 The failure of some (or even most) to tender this recognition is immaterial to the charismatic claim to authority—it is simply the failing of the world to appreciate the truth, something which then serves to further bolster the tight bonds of the charismatic group. As an engendering idea, as a creative and charismatic impulse, the Islamic State demands recognition—a duty that is left to the rest of the world to fulfill. For non-Muslims, the form of recognition is fear, as evinced in Dabiq’s regular articles devoted to the statements by Western leaders regarding the growing threat posed by the Islamic State. For Muslims, the form of recognition is immigration—to respond to the call to abandon life in the West and join the Islamic State, thus recognizing its claim to legitimacy, its leaders’ authenticity and authority as inheritors (khulafāʾ)The term khālifah, 'caliph,' literally means a successor or inheritor, 'one who comes after'; the plural is khulafāʾ. of prophetic leadership. The obligation of immigration, then, proceeds from a charismatic appeal of recognition and is not hampered in the least by the obverse case: the relative rarity of Muslim immigration to the Islamic State and thus the dearth of recognition. In this ideal form, recognition is a duty; the Islamic State is not dependent upon the support or attitudes of others. Failure to recognize the Islamic State does not imply the failure of the State—rather, it is a failure or fault within ourselves (whether Westerners, Muslims or—most intriguingly—Western Muslims).

Understanding the charismatic nature of Dabiq’s call for immigration is critical to understanding the obligation of hijrah. For Weber, pure charisma seeks to overthrow any established social order, setting itself in diametric opposition to stable, routinized society and economy.4 As Weber argues, the rationalized social and economic order is challenged by charisma precisely because “by its very nature [charisma] is not an ‘institutional’ and permanent structure, but rather, where its ‘pure’ type is at work, it is the very opposite of the institutionally permanent.”5 Yet, as S. N. Eisenstadt has highlighted, in Weber’s thinking, charisma is also foundational to building new institutional orders, so that there is a reciprocal relationship between the charismatic appeal and the institutionalization it seeks to create.6 This is because, as Weber argues, the original basis for the stable social and economic arrangements of society lies in an original charismatic moment that establishes a new precedent for provisioning the needs and demands of the society.7

In its “purest” type, this distribution takes the form of gifts and war booty, which are apportioned according to the pure whim of the charismatic leader. This alternative to the economic organization and provisioning of stable society becomes one of the primary vehicles for the charismatic movement to challenge the stable social order. Yet as the movement stabilizes, the charismatic caprice of the former mode is slowly replaced by increasingly bureaucratic and routinized forms, which seek to provision the needs and demands of the society members in a manner that is more organized and predictable over time. Yet the initial charismatic impulse lies at the foundation of new institutions and social arrangements. As Eisenstadt argues elsewhere, institutions retain the capacity to return in part to their original charismatic impulse, as new entrepreneurial figures seek to bring reform and renovation to ossified and stagnant social institutions.8

In this way, just as oil revenues fund the Islamic State’s administration, charisma finances the very construction and operation of the command to immigrate, and sets the claims of the Islamic State into a certain relationship with the West. As a charismatic regime, the Islamic State is imagined to be the very antithesis of Western stability and bureaucracy, whose routinization and standardization stifle the creative impulse that is essential to the charismatic worldview. In order to achieve the utopian vision of the Islamic State, the call to immigrate demands complete abandonment of the West—it is either Us or Them, either the revolutionary charismatic calling or the ossified social structure of the West. To immigrate is not to move from one country to another. It is to abandon a habituated social order in favor of the limitless potential of a conceptual frontier.

It is in this context that the third issue of Dabiq constructs the Islamic State’s claim of immigration over Western Muslims. The issue’s feature article, entitled “Hijrah from Hypocrisy to Sincerity,” lays out the psycho-social realities of immigration.9 Here, the author seeks to address the putative barriers that might impede young (and pronominally male) Western Muslims from leaving the West, including the relative safety, economic security, and educational opportunities represented by Western life. In so doing, the author presents an idea of the West in contrast with an idea of the Islamic State, suggesting what it might mean to belong to either.

In this way, the personal safety of life in the West is neither emulated nor ignored in the Islamic State, but rather turned on its head, so that the promise of pure death in martyrdom is the celebrated opportunity of the charismatic regime. This immediate and intimate access to the charismatic world is essential to the Islamic State’s claims to subvert the rigid, impersonal, and bureaucratic life of the West. Similar themes of immediacy are carried through the article’s critique of the “modern day slavery of employment,” which is contrasted with the right of war booty (including enslavement) as the prophetic inheritance of all Muslims.10 Again, the economic security of Western society is not denied; rather, the purity of the one who “eats from… his sword” is extolled, contrasting the impersonal wage-labor of Western economies with the unique and personalized rewards of the charismatic economy.11 Finally, the article does not deny the opportunities for education—even Islamic education—in the West, but instead invites Western Muslims to apply their knowledge in the building of a new world.

Each case celebrates the experience of immediacy allegedly found in life under the Islamic State—an ideal place where one breaks from the rigid, impersonal, and hierarchical life of the West—without denying the purported (if equally idealized) experience of life in Western society. As commentators standing outside of that social order, the authors of Dabiq are nevertheless responding to it, which can be seen in the very construction of the obligation for hijrah. While invoking Islamic texts and narratives, the charismatic call and authority of the Islamic State articulated in Dabiq is thus intimately connected with Western society as it is imagined by the authors, who then articulate their Islamic alternative in direct relation to the West.

Performing American Islam: The “Open Letter to Al-Baghdadi”

In late September of 2014, in a speech addressed to the UN General Assembly, Barack Obama called upon Muslims all over the world to “explicitly, forcefully and consistently reject the ideology of organizations like al-Qaeda and ISIL.”12 Around the same time, in an interview with CNN’s Christiane Amanpour, John Kerry also asserted that Muslims worldwide would be required to “reclaim Islam” in the greater campaign against ISIL.13 Elsewhere both Obama and Kerry explicitly attempted to attenuate, at least verbally, the relationship between Islam and ISIL. For example in his official statement on ISIL, Obama, channeling the same sentiments expressed by George Bush following the September 11 attacks, insisted that the perpetrators of violence were “not ‘Islamic’” and even remarked that the majority of ISIL targets have been Muslim.14 Much to the surprise and dismay of many commentators, Kerry went a step further and insisted on calling ISIL by the pejorative Arabic term “Daʿesh”A derogatory name for ISIS/ISIL derived from rendering their Arabic name al-dawlah al-islāmiyyah fī'l-ʿirāq wa'l-shām (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) as an acronym, with its insulting connotations variously explained. on the basis that the group’s actions “are an insult to Islam” and therefore should not be called Islamic.15

At best, these efforts by American political leadership to make clear a distinction between Islam and ISIL are well-intentioned, and presumably meant to assist Muslim communities across the globe who might be unfairly associated with violent groups such as ISIL. However, we argue that the sharp imperatives laid out by Obama and Kerry for Muslim communities worldwide to denounce violence enacted by ISIL actually reinforce associations between “Islam” and ISIL in public perception in the United States. By requiring all Muslims to disavow the violence of groups like ISIL, there is an implicit notion that, in essence, there is indeed a link between extremist groups and Muslims unless otherwise noted. Moreover, when the most powerful American political figures construct such a linkage between all Muslims and ISIL, there are significant implications for Muslims in the West. For American Muslims in particular, the seemingly innocuous imperatives made by Obama and Kerry signify that being a part of the American public discourse requires the adoption of certain rules and parameters that have been dictated for them. For example, public discussions over ISIL are restricted to what Islam and the Qurʾān do or do not say about topics such as violence, jihad, slavery, and women’s status. This in turn means that American Muslim leaders can only respond on those same terms. They are required to engage with questions of religious interpretation rather than discuss foreign policy, free market capitalism, and the marginalization of Muslims in the West, all factors that inform the current situation in Iraq and Syria.16

Obama and Kerry represent the hegemonic discourse that establishes what issues are at stake and which questions are of significance. In this context, Western concerns about each and every act of violence perpetrated by Muslims are almost always dictated in religious terms. What is expected of American Muslim leaders, then, is to conform to these expectations by providing a religious response to ISIL. By providing Islamic counter-arguments to the kinds of claims articulated in ISIL publications such as Dabiq, as mentioned earlier, and restricting the discussion solely to matters of religion, American Muslims are forced to accept the rules of the debate. In other words, American Muslims are compelled to acquiesce to a discourse that not only emphasizes religion and theology but also effaces socio-political and material conditions as viable causal factors to understanding the phenomenon of ISIL.

Furthermore, in performing the role that is expected of them, we argue that American Muslims are actually participating in another debate entirely, namely about the legitimacy of Muslim belonging in the United States. Here it is helpful to draw on David Scott’s concept of the “problem space” which is defined as

… an ensemble of questions and answers around which a horizon of identifiable stakes (conceptual as well as ideological-political stakes) hangs. That is to say, what defines this discursive context are not only the particular problems that get posed as problems as such (the problem of “race,” say), but the particular questions that seem worth asking and the kinds of answers that seem worth having. Notice, then, that a problem-space is very much a context of dispute, a context of rival views, a context, if you like, of knowledge and power. But from within the terms of any given problem-space what is in dispute, what the argument is effectively about, is not itself being argued over.17

According to Scott, a “problem space” comprises a specific set of issues that make up the framework of a given debate. This framework is defined by particular questions and answers that are dependent upon various networks of power. However, within this framework of questions, the real topic at hand is not itself acknowledged in explicit terms. For instance, the structure of the American debates over ISIL is determined by the hegemonic power of politicians and mainstream media. In this case, figures such as Obama, Kerry, and even CNN’s Don Lemon—who earnestly inquired if American Muslim human rights lawyer Arsalan Iftikhar supported ISIL (see Gallery Video A)—set the terms of the debate from their positions of power.18 Specifically, they require that Muslims respond to queries on ISIL through the lens of religious commitments and affiliation.

Obama and Kerry both singlehandedly put the burden of responsibility on all Muslims to condemn what is considered “Islamic extremism” as a necessary component of overcoming this complex global phenomenon. Accordingly, in the televised interview with Iftikhar referenced above, Lemon insistently expected him to explicitly articulate his personal position on ISIL. It was not sufficient that Iftikhar had spent the previous five minutes arguing that all Muslims should not be personally held responsible for terror attacks, in the same way that Christian leaders are not asked to be accountable for acts of violence perpetrated by those with a Christian background. Nor did Iftikhar’s background as an international human rights attorney qualify him to be perceived as someone who would naturally be appalled at the actions of a group such as ISIL. Iftikhar’s responses were not considered acceptable precisely because they did not fall within the parameters of the debate. These are clear examples of Scott’s questions and answers “that seem worth asking… and worth having.”19 The only questions and answers that are deemed worthwhile in this context are whether or not all Muslims (and in particular, American Muslims), as people who purportedly share a faith with violent groups, agree with the ideology of ISIL. Furthermore, an endorsement of ISIL is apparently the default stance of all Muslims unless explicit and public apologies and/or condemnations are made (and sometimes despite this). Applying David Scott’s concept of the “problem space” to American debates about ISIL, then, we argue that these debates are not really about the permissibility of jihad and emigration in Islam, nor are they centered on the qurʾānic stance on violence or warfare. Rather, these conversations mask the real issue at stake, which is whether or not Muslims can ever truly belong in North America.

This renders the Muslim role in the West performative, in that it functions as a way to lay claim to American belonging. This role is evidenced through what is popularly known as the “Open Letter to Al-Baghdadi” issued by over 120 prominent Muslim scholars worldwide, including representatives from key North American Islamic institutions such as CAIR, ISNA (Islamic Society of North America) and Fiqh Council of North America, Zaytuna College, ADAMS Center in DC, as well as a few Islamic Studies professors from US institutions. The letter was released on September 24, 2014 and spans seventeen pages of text, with versions available in Arabic, English, French, Turkish, and Persian.20

The letter is intended by its authors to be a dense and meticulous refutation of the ideology of ISIL. It draws exclusively, albeit superficially, on the classical legal tradition, ḥadīth, and Qurʾān in order to delegitimize the Islamic State. The first sections of the letter draw heavily on classical legal tradition (specifically that of the Shafi’ite school) in order to establish scholarly privilege in scriptural interpretation. As such the letter and its signatories emphasize knowledge of uṣūl al-fiqh (exegesis) and a thorough command of Arabic as qualifications needed to quote the Qurʾān to advance a particular position. This is in contrast to the preferred interpretative method of ISIL as seen in Dabiq, wherein any reader can pick up the text and interpret verses in isolation. To this point, the Open Letter asserts that “it is not permissible to quote a verse, or part of a verse, without thoroughly considering and comprehending everything that the Qurʾān and Hadith relate about that point.”21

According to Nihad Awad of CAIR, who presented the letter in a press conference in Washington, DC, the letter was meant to dissuade potential recruits from emigrating for the purposes of jihad. Awad further states that the letter “is not meant for a liberal audience” and that some mainstream Muslims may not understand it either.22 However, we contend that the outwardly complex legal argumentation renders it inaccessible to any potential ISIL recruits as well. Furthermore, the inaccessibility of the letter in our view is a part of the American Muslim performance that emphasizes religious and theological argumentation at the expense of a discussion of socio-political context surrounding the rise of ISIL. The most accessible part of the letter is its executive summary, which comprises twenty-four bullet points, each corresponding to a longer section within the body of the letter. The presence of this executive summary, we argue, signals that the very format of the Open Letter itself appears to be intended for a Western, non-Muslim public. Executive summaries are a standard feature of business and journalistic reports, and not typically utilized in either traditional or contemporary Islamic legal texts.

Interestingly, twenty-two out of these twenty-four points incorporate the statement “it is forbidden in Islam” or “it is permissible in Islam.” For example, point eight reads: “Jihad in Islam is defensive war. It is not permissible without the right cause, the right purpose, and without the right rules of conduct.”23 However, John Kelsay demonstrates the complex ways in which “right conduct” in jihad can be accommodated in multiple contexts, thereby extending the purview of “defensive war” and also allowing for the possibility of offensive jihad.24

Furthermore, we argue here that these definitive statements treat “Islam” as a monolithic entity with a singular stance on various issues, which in many ways is the very same critique that the letter directs towards ISIL ideologues. In fact, the letter’s usage of multiple singular statements on Islam contradicts point four that refers to the allowance for differences of legal opinion within the classical tradition. The signatories of the letter argue for the legal pluralism of Islam, while simultaneously claiming that ISIL is unequivocally “un-Islamic.” These contradictory statements indicate that despite the appearance of complex legal reasoning, the Open Letter only superficially reflects the classical tradition.

Moreover, despite Awad’s assertions to the contrary, the “Open Letter to Al-Baghdadi” does not, in fact, engage deeply with classical religious texts and scholars. It may appear this way to the casual observer because it is laden with technical language and vague invocations of prominent classical scholars. However, the outward complexity and inaccessibility of the letter to Western audiences do not suffice to render it an accurate portrayal of the classical legal tradition. Here, the Open Letter actually mirrors the superficial rhetoric employed by ISIL in Dabiq, which is also laden with references to classical scholars.

For example, in the second point of the letter regarding the centrality of Arabic linguistic expertise, the authors of the letter contend that mastery of Arabic grammar, syntax, and morphology is required to understand legal theory. The letter then makes a distinction between khilāfah and istikhlāf, in order to argue that the latter term signifies settling in a particular place, rather than rulership. As such, ʿAdnānī’s failure to distinguish between the two terms in this same way in his declaration of the ISIL caliphate is cited as a grave linguistic error that stems from his lack of command of Arabic.25 The letter thus dismisses ʿAdnānī’s declaration that the caliphate is a reference to the qurʾānic injunction of “God’s promise” as an inaccurate interpretation of the Qurʾān. However, in our view, this dismissal does not actively engage with the fact that ʿAdnānī is a native Arabic speaker of Syrian background, and according to Shaykh Abū Turkī b. Mubarak al-Binʿalī, one of the leading authorities cited by ISIL for its legal rulings, he is indeed learned in the religious sciences. According to a statement published online by Shaykh Binʿalī, ʿAdnānī memorized the Qurʾān at a young age and went on to study tafsīr, ḥadīth, and fiqh.26 On this basis, ʿAdnānī’s credentials would, in fact, appear to fulfill the scholarly prerequisites as specified in the letter to engage in the interpretative exercise of ijtihād.

Furthermore, multiple sections of the letter draw on Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad b. Idrīs al-Shāfiʿī’s (d. 820) teachings in a selective manner when it bolsters particular claims against the legitimacy of ISIL. It appears to gloss over and omit selections of Shafi’ite teachings that might, in fact, support ISIL’s claims. For example, drawing on David Vishanoff, Kecia Ali describes “linguistic ambiguity” as a key element of Shafi’ite legal theory. Ali and Vishanoff demonstrate that Shafi’ite hermeneutics allow jurists to interpret texts in multiple ways, even while championing a singular interpretation as objectively true in accordance to divine intent.27 This indicates that the very same Shafi’ite hermeneutic that is advanced in various parts of the Open Letter could conceivably be used to advance certain aspects of ISIL ideology.

The appearance of complex legal reasoning in the letter constructs an authentic neo-traditional style of argumentation by drawing on the classical sources, which by necessity is lengthy and somewhat inaccessible. This very inaccessibility, however, appears deliberate, because it ultimately serves to persuade non-Muslim audiences of its authenticity. As Awad said in the press conference, “the letter will still sound alien to most Americans… it is using heavy classical religious texts and classical religious scholars.”28 Yet, the letter publicly demonstrates moderate Western Muslims actively taking control of their tradition’s narrative, and performing the role that is expected of them by figures such as Obama and Kerry. This performative aspect of the letter is further played out on the Internet. The letter has its own website where users are invited to add their signature to the letter, and then publish their endorsement on Twitter and Facebook. This provides a way for Western Muslims to publicly condemn ISIL through their personal social media accounts with the authoritative backing of respected religious scholars. This highlights that public condemnation of ISIL is the requirement established for Muslims by the hegemonic discourse.

Awad further contends that the letter “is not meant for a liberal audience,” but rather for those might be attracted to ISIL recruitment.29 However, we argue that this Open Letter is indeed meant for a Western liberal audience. Most of the points in the executive summary appear designed to allay specific Western anxieties about ISIL. For example, point seven clearly states, “it is forbidden in Islam to kill emissaries, ambassadors, and diplomats; hence it is forbidden to kill journalists and aid workers.”30 This is in direct reference to the killings of the two American journalists, James Foley and Stephen Sotloff, and British aid worker David Haines, who are all mentioned in the letter by name. Foley, Sotloff, and Haines were hostages of the Islamic State who were all beheaded only a few weeks prior to the release of the letter, and so at the forefront of public consciousness. Their executions are described as “unquestionably forbidden (haraam).”31 The inclusion of these British and American names as emissaries serves as further evidence that this letter is aimed towards a non-Muslim Western audience, given that there was no mention of the seventeen Iraqi journalists who had also been killed by ISIL in preceding months.

In highlighting some of the internal contradictions present in the “Open Letter to Al-Baghdadi,” it is not our intention to suggest that the authors and signatories of the letter are disingenuous in any way. Rather, we seek to emphasize that the superficiality with which the letter engages with classical religious argumentation in its refuting of ISIL confirms its primary role in another debate, that is, the issue of American Muslim belonging. The chief purpose of the letter, in our view, is to argue for the legitimacy of Muslims in American society. While the authors of the letter may not necessarily be conscious of this masked debate, they are nonetheless actors who partake in this discourse of belonging. The rules of the hegemonic discourse as articulated by Obama and Kerry are such that any discussion of ISIL by Muslim leaders must necessarily address theology. American Muslim debates on ISIL and the demand that all Muslims must publicly condemn the Islamic State clearly demonstrate that Muslims must struggle to claim a place in American society that they currently do not have. We argue, then, that Western Muslim debates over the (im)permissibility of jihad and emigration to join ISIL are less about rival interpretations of Muslim legal texts and scripture, and rather speak more to the discourse of Muslim belonging in North America.

Challenging the Islamic State: Muslim institution building in the West

Many key voices in American politics have responded to the ideological challenges of the Islamic State by emphasizing the role and responsibility of the Western Muslim community as the vanguard of an anti-Islamic State religious discourse. While some politicians have made efforts to draw public attention to the diversity of Muslim belief on issues of violence and terrorism, this strategy also runs the risk of alienating Muslims in the West, who are told that the expression of a vocal stance on the Islamic State is the criterion for their acceptance in the West (just as the Islamic State claims their hostile posture towards Western states and society is the criterion for their acceptance under Islam). Such strategies have done tremendous damage to the establishment of social trust by making narratives of conflict essential to narratives of belonging.

Given the charismatic claims of the Islamic State and the awkward social positioning of American Muslims, what might be a more constructive approach to promoting both civic participation and ownership of American Islam? For Weber, the charismatic orientation towards society arises out of “times of psychic, physical, economic, ethical, religious [or] political distress.” 32 While Weber himself did not elaborate a great deal about these conditions, Eisenstadt has argued that this occurs when the rigidity of the prior social order fails to provide a sense of shared meaning and belonging to its members. Yet charisma is not only found in these moments of catastrophe; rather, as Eisenstadt has suggested, charisma plays a vital and productive role in much more mundane situations as well, particularly in reforming and transforming social institutions. For Eisenstadt, the original charismatic drive of the institution—which first led to its formation—provides later institutional actors with the resources to remap powerful symbols and reorient the institution to address new challenges in ever-changing social conditions. In this way, robust institutions are both the counterweight to claims of authority derived from pure charisma, as well as the filter through which charisma may be channeled into vital and sustaining social work. In the struggle to determine who speaks for Islam, then, Western Muslim institutions are ideally situated to contest Islamic State narratives primarily because they have recourse to the same charismatic potential.33

Productive examples might be drawn from Germany and the Netherlands, where the state has engaged with and even supported local Islamic institutions, resulting in greater access to civic and political participation for Muslim minority communities. As Ahmet Yükleyen has argued, these institutions have played a central role in the process of integrating Muslim immigrant communities. Such organizations, Yükleyen argues, vitally serve to “negotiate between the social and religious needs of Muslims, on the one hand, and the social, political, and legal context of Europe, on the other.”34 In this way, the ability of German and Dutch Muslim communities to engage the state is largely determined by the successful establishment of the communities’ institutions. Comparing Moroccan and Turkish communities in the Netherlands, Yükleyen notes that