PDF

Download

Citations

Click and drag then release to select a passage to cite.

Annotations

How to submit annotations to Mizan Journal articles:

your work is published.

Search within

Memories of Migrations

Refugees in Medieval Antioch

Image

Audio

Video

Chart or Graph

Memories of Migrations

Refugees in Medieval Antioch

وكان أهل طرسوس والمصيصة قد أصابهم قبل ذلك بلاء وغلاء عظيم، ووباء شديد، بحيث كان يموت منهم في اليوم

الواحد ثمانمائة نفر، ثم دهمهم هذا الأمر الشديد فانتقلوا من شهادة إلى شهاد أعظم منها.

The people of Tarsus and Mopsuestia had already been wounded by great affliction, hyperinflation, and intense disease, to the point that 800 of them were dying every day. Then this harsh command came upon them suddenly, and so they were carried from one martyrdom to an even greater martyrdom.

—Ibn Kathīr (d. 1373), al-Bidāyah wa-al-nihāyah

On August 16, 965, the citizens of Tarsus surrendered to the army of Emperor Nikephoros II (r. 963-969) and the city became a Roman/Byzantine possession for the first time in over a century. In exchange for the peaceful surrender of the city, its Muslim residents were allowed to take what they could carry and move to Antioch and other locations that were still in Muslim-ruled territory. By the end of the year, Antioch was in open rebellion against its ruler, the emir of Aleppo, and in 969 it too fell to the advancing Byzantines. Were the refugees from Tarsus to blame for this political chaos and collapse? Several of them were at the head of the rebellion, and—then as now—there must have been angry residents ready to blame them for all the ensuing disasters. Even an otherwise careful scholar might be tempted to describe the conflict as a result of the influx of refugees, not to mention someone seeking to use the past for their exclusionary present purposes. Yet a closer reading of the sources shows that the ambitions of imperial powers and elite Antiochians were more to blame than the refugees from Tarsus. Here I argue that historians must treat past refugees with the sort of understanding that is necessary in our interactions with present refugees, neither stripping them of all agency nor blaming them for negative outcomes over which they had no control.

Theoretical Foundations

Within the broader field of migration studies, forced migration studies has come to prominence in recent decades, spurred by major refugee crises that in some cases continue today. Forced migration can be caused by such issues as environmental change and crisis, human trafficking, religious persecution and other human rights violations, and violent conflict, the last of which is the most relevant category for my discussion here. Violent conflict itself has been disaggregated into a number of subcategories by Sarah Kenyon Lischer: “international conflict” includes border wars, third party (or “multilateral”) intervention, and invasion, while “civil conflict” includes civil war, genocide, failed states, and persecution.1 Each type of conflict has unique characteristics that can be analyzed productively and applied to a historical circumstance such as the conflicts in Cilicia and Syria in the 960s, while the historical data can also be used to critique our assumptions about the content of the categories. Naturally, conflict in the tenth century may differ from contermporary ones, and caution must be exercised in applying modern categories to map violent struggles of the distant past.

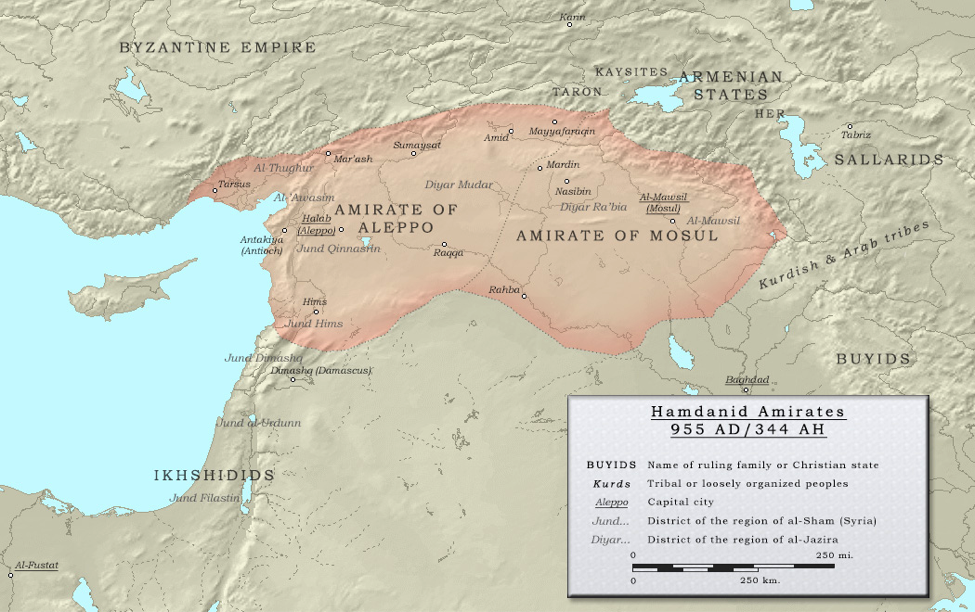

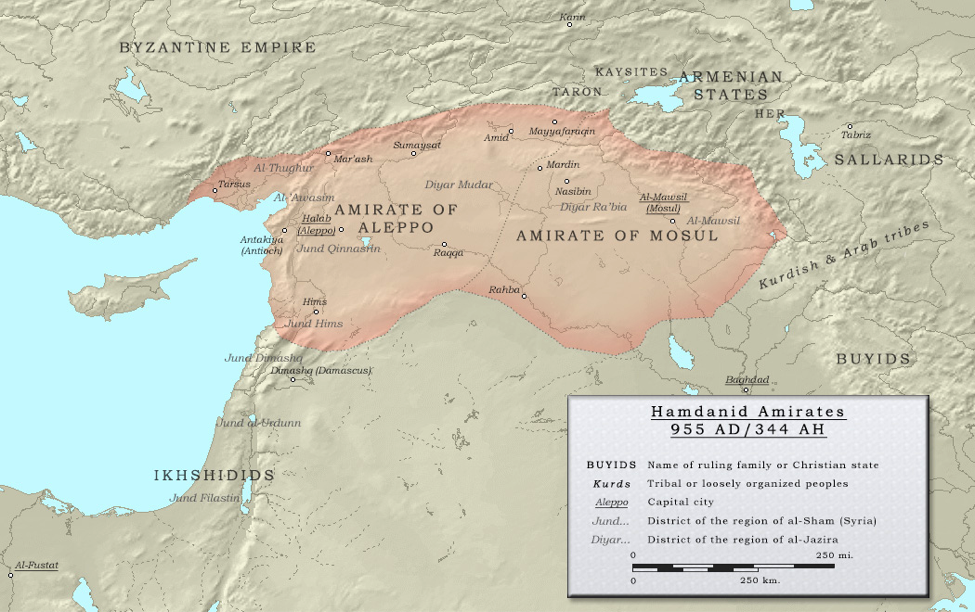

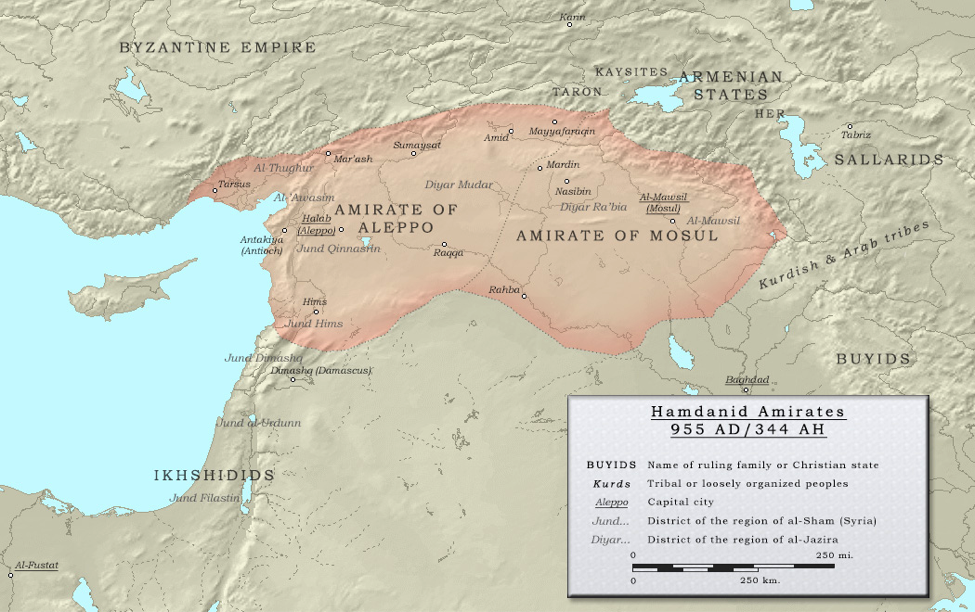

Nevertheless, if I were to categorize the conflicts under discussion here, I would argue that the conflict began with an invasion of Cilicia (including Tarsus) by the Byzantine army, producing a major forced migration, then was followed by a civil war within the territory of northern Syria ruled by the Ḥamdānid emir Sayf al-Dawlah (r. 945-967), even approaching the characteristics of a failed state. However, these internal conflicts and crises do not seem to have caused a migration crisis on any level approaching that caused by the Byzantine invasion, pointing to the power of the imperial authorities in commanding and effecting migration to a far greater extent than occurs “organically” in internal conflicts. Meanwhile the invasion continued apace, with Antioch too falling four years after Tarsus. The Byzantines were certainly interested in seizing territory and reshaping its population, but in the end, they maintained the Ḥamdānid government as a client state in Aleppo rather than overthrowing it entirely.

Figure 1: Map of Ḥamdānid territory in approximately 955. © Ro4444 / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0

Idean Salehyan and Kristian Skrede Gleditsch have written on the need to view forced migration and conflict within a context large enough that it is not bound by the recognized borders of nation-states, as the movement of large groups of refugees can create social networks that cross borders.2 This is especially important when we examine a period in which “nation-states” as we know them did not exist, when borders were not always precisely defined and changed more commonly than they do today. After all, states themselves, even today, are constructed and historically contingent.3 An empire establishing and defending its borders and collecting taxes is involved in the ongoing process of constructing its own state, and when rebels attempt to overthrow their ruler and establish themselves independently they are seeking to do the same.

Salehyan and Gleditsch also discuss the potential for refugee movements to spread conflict across borders, a phenomenon that seems to be in evidence in the 965 rebellion in Antioch. They emphasize, however, that “most cases of refugee flows do not lead to violence” and that “there is clearly no reason to expect deterministic links between refugees and conflict.”4 The events of the 960s provide an opportunity to test their theses on the relationship of refugees and conflict, lending further weight to the argument that the arrival of refugees in Antioch was not the cause of the rebellion and ensuing civil war, even if it may have been exploited by local and governmental actors with their own interests. Even if “refugees from neighboring countries can increase the risk of intrastate conflict,” this does not mean that the refugees are the cause of such conflict, though anti-refugee political actors often seek to blame them for it.5

More broadly, this points to one of the key questions in forced migration studies, the question of refugees’ agency. It is important not to overlook the role of refugees and other migrants in determining their own future, though it can often be tempting to conceptualize them as pawns at the mercy of more powerful forces.6 Terms such as “forced” migration can unfortunately contribute to the assumption that migrants are powerless, and it is important to recognize the choices that they make in the face of difficult circumstances. On the other hand, in situations where civil conflict follows upon the arrival of refugees, an excessive emphasis on the choices made by the refugees can lead observers to blame them for the suffering and chaos that ensues. Even as we recognize the agency of refugees, we must not make them responsible for everything that happens around them, keeping in mind that there are far more powerful actors with a role to play as well. The refugees who arrived in Antioch sparked difficult discussions there, to be sure, but the inhabitants of the city could have made different decisions when faced with this “inevitable contingency,” to use Doreen Massey’s terminology, referring to the unexpected juxtaposition of locals with new arrivals that may spark antagonism, and “is revealed in particular fractures which pose the question of the political.”7 In sum, Northern Syria was not fated to be consumed by conflict when the refugees arrived. Let us turn now to examine the processes by which the region was reshaped in this time of often violent encounter.

The Story: A First Look

I will begin with a summary of the story in order to introduce the key characters and events and show how a cursory reading might be used to demonize the Tarsian refugees as the cause of the Antiochian rebellion and the ensuing warfare and chaos. Muḥammad ibn al-Zayyāt was the governor of Tarsus appointed by Sayf al-Dawlah, but the Byzantine armies were approaching. Both before and during his reign as emperor, Nikephoros II Phōkas was renowned for his Muslim conquests. In 962, he came for Cilicia and Syria, and he took Anazarbus (‘Ayn Zarbah), northeast of Tarsus, with little opposition, massacring many of its inhabitants despite an earlier promise of safety. Yaḥyā ibn Sa‘īd Al-Anṭākī (11th century) notes that many of the survivors made their way to Tarsus, providing another layer to the issue of refugees and conflict.8 Ibn al-Zayyāt, no longer convinced that loyalty to Sayf al-Dawlah could ensure the safety of himself and his city, ordered the local preachers not to mention the emir’s name in their Friday sermons—a traditional way of demonstrating a change in political allegiance—and led an army to fight Nikephoros outside the city. The loyalty of Tarsus was thus already suspect.

Ibn al-Zayyāt’s army was decimated by the Byzantines, and even the governor’s own brother died in the battle. Though Tarsus itself was not attacked, the people turned against their governor, returned Sayf al-Dawlah’s name to the sermons, and sent him a message declaring their renewed loyalty. At this point, the sources diverge somewhat regarding the fate of the governor. Miskawayh (d. 1030) and Ibn al-Athīr (d. 1233) claim that Ibn al-Zayyāt committed suicide by jumping into the river from the balcony of his waterfront house, with the implication that this occurred in 962 or shortly thereafter, but Ibrāhīm ibn Yaḥyā (10th-11th century) and Yāqūt al-Rūmī (d. 1229) claim that he was still alive and played a role in the surrender of Tarsus three years later.9 Ibn al-‘Adīm (d. 1262) insists that Ibn al-Zayyāt was no longer in power and that control of the city had passed to his subordinate Rashīq al-Nasīmī, a favorite among the people of Tarsus and an ostensible ally of Sayf al-Dawlah, some time before the conquest.10 The claims are ultimately irreconcilable.

In any case, the sights of the Byzantines were set on Cilicia again three years later, specifically on Mopsuestia (al-Maṣṣīṣah) and Tarsus, after an unsuccessful 964 attack on Mopsuestia. Even before the summer 965 season of hospitable weather and warfare began, the rulers of these cities had sent a messenger to Nikephoros (now emperor) at his winter retreat in Caesarea, seeking an arrangement by which they could pay tribute and align themselves with imperial power. The Ḥamdānid loyalty of the border cities was hanging by a thread. Nikephoros was initially open to such an arrangement, but when he heard how bad the situation was in Cilicia—where the people of Tarsus were so hungry that they were eating dogs and carrion—he was furious that they were seemingly taking advantage of his generosity. He placed the letter on the messenger’s face and set it on fire, burning the messenger’s beard, and compared the Cilicians to a hibernating snake that would eventually wake up and bite him if he did not attack them and put them in their place. Finally, he told the messenger to warn Mopsuestia and Tarsus that he had “nothing but the sword” for them, and he set out for war.11

The emperor first conquered and devastated Mopsuestia, slaughtering many of its inhabitants, but when he reached Tarsus he had a change of heart— the Christian polymath Bar ‘Ebrāyā (d. 1286) claims that when he heard the groans of its suffering people, his heart was grieved—and accepted the people’s pleas for a peaceful surrender.12 He treated its people well and honored its leading men at his own table, but ordered that its Muslim inhabitants must either vacate the city, convert to Christianity, or submit to his rule and pay a special tax. Yāqūt, quoting an eleventh-century source who had personally interviewed some of the refugees, presents a dramatic scene in which Nikephoros set up two banners and offered the people of Tarsus a choice between the good governance of his Christian empire and the sinful, unjust realm of the Muslims.13 Most of the Muslims of Tarsus chose to leave—Ibn al-‘Adīm says as many as 100,000, though such numbers are difficult to verify—and the bulk of these migrants ended up in Antioch.14 Their condition was bleak, having survived the ravages of intense famine, hyperinflation, and plague, and Ibn Kathīr says that Nikephoros’s resettlement order “came upon them suddenly, and so they were carried from one martyrdom to an even greater martyrdom.”15

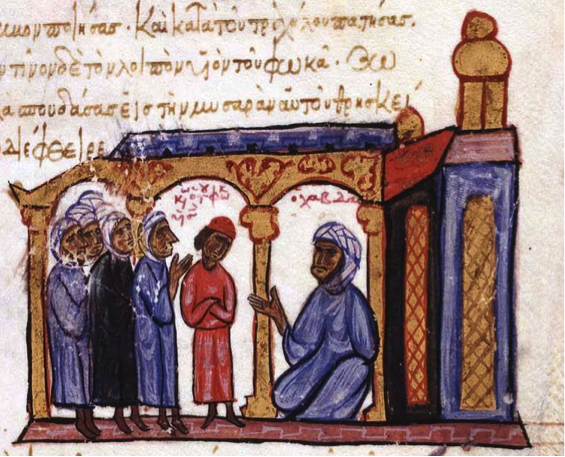

Figure 2: Battle between Byzantine and Arab armies in Cilicia, 950. National Library of Spain VITR/26/2, fol. 136v

There is general agreement among the sources that Nikephoros was surprisingly kind to the refugees, providing a military escort to ensure their safe arrival in Antioch (well over 100 miles away) and ships if they wished to go elsewhere. They were allowed to bring some of their possessions as well, though there is some disagreement here: most sources agree that they could take as much as they could transport, but Leo the Deacon (10th century) claims that they were allowed to take “their own bodies and only the necessary clothing,” perhaps exaggerating their destitution in order to emphasize the power of the emperor and the suffering of the enemy.16 Yāqūt adds that they had to pay the Byzantines for means of transportation for their goods and that the Byzantines charged exorbitant prices, about a third of each person’s possessions.17 More importantly for our discussion of the ensuing rebellion, most sources agree that the refugees were allowed to take their weapons with them. Ibn al-‘Adīm claims the opposite, but this may be a mistaken claim on his part or an error in transmission, because the other sources unanimously declare that the refugees arrived in Antioch fully armed.18

Nikephoros, it seems, was fully aware of the significance of conquering Tarsus, which had long been a base for raids on Byzantine territory and thus had an unusually large population of military personnel. According to Ibn al-‘Adīm, the emperor climbed the pulpit of the main Friday mosque and asked the soldiers around him, “Where am I?” When they responded that he was on the pulpit of Tarsus, he answered, “No! Rather, I am on the pulpit of Jerusalem, for this [city] was keeping you from that one.”19 Most sources report that the emperor then converted the Friday mosque into a stable and burned its pulpit, while Yāqūt claims that he destroyed all the mosques and burned the city’s Qur’ans.20 He refortified the city and its economy improved enough that many natives returned in the coming years. Some converted to Christianity, though others remained Muslims and paid a special tax. Bar ‘Ebrāyā adds, however, that all children in Byzantine Tarsus were baptized, whether their parents were officially Christian or not.21

Sayf al-Dawlah, meanwhile, was suffering from chronic paralysis and attempting to recover in far-off Martyropolis (Mayyāfāriqīn), his second capital, and the people of Cilicia and Syria were growing more and more impatient with his inability to protect them from the invaders.

The people of Antioch were suddenly faced with the arrival of many thousands of armed refugees, bearing news of the power and looming threat of the Byzantine army. The governor of Antioch, named Fatḥ, was overwhelmed. Ibrāhīm reports that the Antiochians asked the newly arrived Ibn al-Zayyāt, who he believes was still alive (perhaps confusing him with Fatḥ), to take control of their city and keep things from falling apart any further.22 However, he adds that Ibn al-Zayyāt was so afraid of Nikephoros that he refused.

In any case, neither Fatḥ nor Ibn al-Zayyāt remained in power, and the Antiochians chose Rashīq, another new arrival, to replace their previous leaders. Ibrāhīm tells us that Rashīq’s main advice to the Antiochians was to surrender to Nikephoros and make a deal with him, no doubt informed by his recent experience in Tarsus.23 He argued “that this was the way of prosperity and that they would never attain the perfect calm and tranquility that they desired if they did not obey” the emperor.24 When they sent emissaries to Nikephoros, however, he was not receptive to their pledges of loyalty and offers of money, responding:

As for money, I do not accept it because the king of the Romans has no need of it, and because the Muslims might give it today and refuse it tomorrow. Nor do I accept pledges, because while they have meaning for some people, most do not even think about them. I only request one thing, whenever you wish and whenever you realize that it is an easy and insignificant thing for you to fulfill. That is, I wish to build a fortress on a rock formation within your city, in which I will have a general [stratēgós]25 and a small number of others to defend you, and by means of them I will conquer.26

The Antiochians refused to allow this imperial intrusion into their local autonomy and rejected the offer. Rashīq was ashamed by the failure of his diplomatic strategy, and as he felt “useless,” he decided to try a different approach: armed revolt against Sayf al-Dawlah. He quickly removed the emir’s name from the Friday sermons and had a letter read publicly that purported to be from the ‘Abbāsid caliph in Baghdad, authorizing him to rule the area.

Rashīq was joined by al-Ḥasan ibn al-Ahwāzī, a wealthy Antiochian, and they assembled an army to move on Aleppo. A band of soldiers were there from Daylam, in northern Iran, and they submitted to Rashīq along with their leader, Dizbar al-Daylamī.27 The bulk of the city surrendered quickly, but Sayf al-Dawlah’s representative Qarghuwayh was able to barricade himself within the nearly unassailable hilltop citadel, which therefore remained in loyalist hands, just as it had during a Byzantine invasion in 962. Rashīq and his allies laid siege to the citadel of Aleppo for three months and ten days, with heavy fighting between the factions on a daily basis. Eventually, after Sayf al-Dawlah sent reinforcements led by a Black servant named Bishārah, Rashīq fell from his horse during a battle and was killed. Ibn al-‘Adīm tells us that the killer was Abū (or Ibn) Yazīd al-Shaybānī, a soldier of Sayf al-Dawlah who had previously made an alliance with Rashīq, and that Abū Yazīd cut off Rashīq’s head and brought it triumphantly to Qarghuwayh.28 Other accounts vary in details, but all agree that Rashīq died in battle and his allies retreated to Antioch. Ibn al-‘Adīm says that Rashīq’s death was “lamented.”29

Back at their starting point, the rebels regrouped. Dizbar was named emir and took control of the movement, with Ibn al-Ahwāzī remaining as vizier, and a descendant of the Prophet named Abū al-Qāsim al-Afṭasī was brought on board as “caliph” to provide religious legitimacy.30 Qarghuwayh and the loyalist forces hoped to press their advantage and moved quickly toward Antioch, where they were defeated and repelled after some initial successes. The rebels fought their way to Aleppo once again, and Ibn al-‘Adīm claims that they were able to capture the entire city, including the citadel, in April or May of 966.31 He adds that they began to set up the bureaucracy of their nascent state, appointing judges and other governmental officers, and collected taxes from cities throughout the region. Most sources do not say that Aleppo fell, however, and al-Anṭākī in particular states that the rebels were repulsed from Aleppo as they had been before.32 Whatever the case, around this time Sayf al-Dawlah was finally feeling well enough to make the journey from Martyropolis, and he came with his armies to put down the rebellion once and for all. He captured Dizbar and executed him immediately, and though Ibn al-Ahwāzī had hidden himself with a local tribe, a ransom secured his delivery to the emir. Sayf al-Dawlah put him in prison temporarily, but when the Byzantines began to advance again, the emir did not want the prisoner to distract him from the war effort, so he had him executed as well.

Despite the return of Sayf al-Dawlah, things continued to be chaotic and unstable, especially in Antioch. In fact, the emir died in 967—at which point some resentful Antiochians assassinated Christopher, the Christian patriarch, who had remained loyal to Sayf al-Dawlah throughout the rebellion and its aftermath—and his son Sa‘d al-Dawlah (r. 967-991) found it difficult to secure his rule. Qarghuwayh established himself as the largely autonomous ruler of Aleppo, while control of Antioch bounced rapidly from its Ḥamdānid-appointed governor Taqī al-Dīn, to Muḥammad ibn ‘Īsَā and his group of Khurāsānī soldiers, to a Kurd named ‘Allūsh, to a black man named al-Rughaylī. This final leader, as Ibrāhīm and al-Anṭākī tell us, had actually been a refugee from Tarsus himself, at first fleeing to Egypt, then returning to Antioch with a group of soldiers to fight the Byzantines, and eventually taking control of the entire city by assassinating ‘Allūsh in his own court.33

Finally, the Byzantines conquered the collapsing city from al-Rughaylī on October 28, 969. Ibn al-Athīr and Bar ‘Ebrāyā tell us that they were aided by the inhabitants of the fortress of Lūqā, which they had also recently captured.34 The people of Lūqā, who were Christians, made an agreement with the conquerors and fled as refugees to Antioch, but then betrayed and overthrew the city from within, providing secret information to the Byzantine army. Once again, it seems that refugees were at the heart of the fall of Antioch, easily blamed for its misfortunes. The city remained in Byzantine hands (despite several rebellions and other displays of anti-imperial sentiment) until 1084.

Another Reading

Ibn al-‘Adīm’s Bughyat al-ṭalab (1988, 8:3656) is the only text to describe the journey of the Tarsians to Antioch using the verb iltaja’a or “seek refuge,” which is related to lāji’, the standard term for “refugee.” They were forced from their homes by an invading power and likely stripped of many of their possessions, especially their houses and other immovable goods. They had the option to convert to Christianity or pay a special tax—similar to the jizya assessed on religious minorities in Muslim-ruled territories—but most decided that flight was the best available option.

This created a refugee crisis in Antioch, where many thousands of new residents were arriving simultaneously, telling tales of the powerful invading army they had left behind. The Antiochians must have hoped that they could reach an agreement with Nikephoros like the one reached in Tarsus, as opposed to the situation in Mopsuestia where massive numbers had been massacred. They turned to those who had the relevant experience—Ibrāhīm claims that Ibn al-Zayyāt was still alive and was asked first, but most sources simply say that the Antiochians chose Rashīq to be their leader. When negotiations with Nikephoros failed, Rashīq decided to “uncover his head” in rebellion, and the violence of invasion became the violence of civil war, to use Lischer’s categorization.35 Just as Salehyan and Gleditsch have described, a refugee crisis was followed by a spillover of violence into their new host country, and we are faced with a situation in which a refugee crisis was not merely the result of violence, but also a contributing factor in its spread.

There must have been plenty of Antiochians who opposed the idea of putting a newly arrived refugee in charge of their affairs, as well as those who blamed Rashīq when the negotiations fell through and the rebellion failed. Our own experience with refugee crises shows how quickly discourses of identity and place can be turned against newcomers, especially when conflict follows upon their arrival and outside threats exacerbate the stress of the situation. Throughout the story, “foreign” elements seem to be at the center of so many Antiochian tragedies: Ibn al-Zayyāt, Rashīq, and al-Rughaylī from Tarsus; Dizbar and his soldiers from Daylam; the Christian infiltrators from the fortress of Lūqā.36 Did the medieval historians blame the refugees for the ensuing disasters, and should we do so today? Was such civil conflict unavoidable?

First, it is important to recognize, following Massey, that none of this was inevitable, and that tenth-century Antioch, like all other places, was characterized by the “inevitable contingency” that poses “the question of the political.”37 The Tarsian refugees, including Rashīq, had considerable agency despite the constraints of their situation, as did the prior residents of Antioch. The Antiochians chose Rashīq as their new leader, and Ibrāhīm claims that their previous choice turned down the job out of fear of the Byzantines. They then chose, on Rashīq’s advice and in hope of peace and prosperity, to seek a diplomatic solution with Nikephoros, and when this fell through, it was Rashīq who chose what he thought was the best path forward for himself and his neighbors, rebellion against the Ḥamdānid government. Throughout this process, the sources describe little obvious tension between the refugees and the other Antiochians. Thus, when the people of Antioch—refugees and non-refugees—made the choice to rebel, they were simply choosing to engage in the process of forming a new state, since their current government did not seem to be able to provide the basic threshold of safety necessary for legitimacy, and the Byzantines did not accept their offer of tribute. Once the rebellion was suppressed, it became easier to view Sayf al-Dawlah as the legitimate ruler throughout the period, but this would by no means have been obvious to someone in the midst of the events. These challenges to the status quo reflect the agency of the people on a grand scale, though ultimately their attempt at state formation fell apart.

On the other hand, much more powerful actors were involved at the same time. Rashīq and the other refugees were making choices within the constraints presented to them, but in large part those constraints were constructed by powerful figures like Nikephoros. After all, though Rashīq chose—in consultation with the people of Antioch—to seek a negotiated settlement and to rebel when that settlement failed, it was Nikephoros who decided to reject the offer of the diplomats. The emperor did not directly bring about the Antiochian rebellion, but he played the most important role in constructing the conditions in which such a rebellion seemed an attractive option to the people of Antioch. Similarly, Sayf al-Dawlah’s choice—and the choice of rulers across the Islamic world—to send inadequate support to the Cilician/Syrian border meant that the Antiochians felt the Ḥamdānids could no longer provide for their safety. Their choice to rebel, in such a situation, is understandable, but it is also easy to see how it was shaped by larger forces.

In addition, the role of the non-refugee Antiochians should not be overlooked simply because Rashīq was the leading figure at the beginning of the rebellion, and a closer look at the medieval sources reveals that they do not fail to discuss other actors. Here the figure of Ibn al-Ahwāzī, the sole constant presence from the beginning of the rebellion to the end, deserves more attention than I have given him previously. His background and pre-rebellion career are somewhat unclear from the sources, but it seems most probable that he had been appointed as a government official supervising the mills and agricultural proceeds of Antioch.38 Whatever his position, he had access to enough money that he could essentially fund the rebellion independently—perhaps by taking advantage of funds that were supposed to be used for government projects, but also by calling in some loans and generally shaking down the Antiochian populace. Miskawayh calls him “a person of little rank” and Ibn al-‘Adīm calls him “disreputable.”39 Throughout the sources, no figure in this story is more negatively presented than Ibn al-Ahwāzī.

This “disreputable” man not only funded the rebellion, he played the biggest role in ensuring that it would take place. He encouraged Rashīq to rebel and told him that Sayf al-Dawlah’s illness made it impossible that he would ever return to Syria, a prediction that eventually proved unfounded. According to Ibn al-‘Adīm, Ibn al-Ahwāzī was the one who crafted the letter falsely claiming to be from the ‘Abbāsid caliph al-Muṭī‘ (r. 946-974), which gave Rashīq authority over the holdings of Sayf al-Dawlah and was read aloud from the pulpit of Antioch’s mosque at the beginning of the uprising.40 A similar letter was read in Aleppo when the rebels were in control of most of the city. Thus, though he largely worked behind the scenes, the rebellion would be almost unthinkable without the assistance and encouragement of Ibn al-Ahwāzī, apparently a native Antiochian—or at least, not a refugee from Tarsus.

Ibn al-Ahwāzī also had extensive control over the day-to-day operations of the rebels, serving as vizier and primary administrator although the official authority was in the hands of others. When Rashīq was killed and the rebels had to regroup in Antioch, Ibn al-Ahwāzī seems to have been the driving force behind the appointment of Dizbar and al-Afṭasī to leading roles in the movement. Ibrāhīm writes that despite their defeat and the death of their leader, all of them “remained firmly committed to their opposition and rebellion. The one who encouraged them in this was a person of Antioch named Ibn al-Ahwāzī, an intense, dynamic, and active person, and he had been the manager of their affairs in the time of Rashīq.”41 Upon Rashīq’s death, Ibn Kathīr says that Ibn al-Ahwāzī “became independent,” taking over leadership of the movement until Dizbar could be appointed, and he seems to have been the primary power behind the throne throughout the uprising.42

When he heard that Christopher had fled the city to avoid appearing to be a rebel sympathizer, Ibrāhīm and al-Anṭākī tell us that it was Ibn al-Ahwāzī who became furious and began to mistreat the Christians of Antioch in retribution.43 He arrested and otherwise harassed some of Christopher’s closest associates and sealed up the possessions of the Church in the patriarchal residence. Likewise, his designated “caliph,” al-Afṭasī (who was given the nickname al-Ustādh, “the Teacher”), is said to have oppressed the people of Antioch and inappropriately amassed wealth from them. Nevertheless, perhaps because of his relatively low profile, Miskawayh tells us that Ibn al-Ahwāzī still had enough support from “the people of the town” that together they were able to fight off Qarghuwayh’s offensive.44 This again shows the unity of those in Antioch, whether newly arrived refugees or longtime residents, in fighting off the emir of Aleppo and his loyalist army. Ibn al-Ahwāzī was, as Ibn Kathīr says, well established in Antioch.45

It is difficult to tell exactly why Ibn al-Ahwāzī played—and it seems did so deliberately—a behind-the-scenes role in the Antiochian rebellion. Perhaps he was used to the less public life of a government bureaucrat and wanted to find more charismatic leaders to serve as the faces of the uprising, or perhaps he thought he could avoid accountability if it failed. It is also possible that he wanted to find outsiders—first Rashīq, then Dizbar—to bear responsibility for his own risky undertaking. Whatever the reason, the medieval historians place most of the blame for the rebellion, and its failure, on Ibn al-Ahwāzī, and present him as essentially a moderately wealthy and corrupt Antiochian of middling social status who took advantage of the refugee crisis to provoke a rebellion by which he stood to gain much more wealth and prestige. It is notable that they all take this position rather than blaming the refugees, even when the rebellion was first led by one of the new arrivals.46 In fact, of all the people in Antioch, Patriarch Christopher is the only person who is explicitly said to have opposed the rebellion, though there must have been plenty of others. Even one of Christopher’s closest friends, a Christian leader named Theodoulos, came to the monastery to try to convince him to rethink his position and return to the city, but the patriarch stood firm.47

Conclusion

Reading this history through the theory of Salehyan and Gleditsch, it at first seems simple: as the authors describe, the arrival of the refugees constituted the arrival of arms and combatants, or potential combatants, from the neighboring Cilician region.48 It is likely that they also competed with the locals over scarce resources, another of the four ways that Salehyan and Gleditsch describe the spread of conflict in situations of forced migration. The other two paths to conflict are focused on ethnicity, which does not seem to have been as much of an issue in tenth-century Antioch: the migrants from Tarsus likely included a similar ethnic mix to that of the already highly diverse cities of northern Syria, including people from all over the Islamic world and beyond, although they must have had a much larger percentage of Muslims than the previous residents of Antioch. Still, it is clear that much of the theory expounded by Salehyan and Gleditsch describes the situation well. In fact, it seems especially fitting to speak in terms of “refugees and the spread of conflict,” as the rebellion was itself led by a refugee.

On the other hand, a closer reading of the medieval historians, as demonstrated above, reveals that they do not actually blame Rashīq or the refugees as a group for the rebellion and the ensuing disasters in Antioch. If anyone, they place primary responsibility on the shoulders of Ibn al-Ahwāzī, and throughout their accounts it seems obvious that Antiochians of all sorts were essentially unified in their hope for greater autonomy. They exercised agency despite the constraints of their situation, and they lived in the contingency of space described by Massey. The space of northern Syria, “the sphere of the possibility of the existence of multiplicity,” was shaped and reshaped by their choices in unpredictable ways.49

Nevertheless, of course it remains true that the Byzantines, and even the Ḥamdānids, had a greater influence on the course of events than the rebels of Antioch. It is impossible, at this distance, to know whether Nikephoros intentionally turned down the Antiochian offer of tribute in the hope that a doomed rebellion would break out, but things certainly worked out well for him as the entire region collapsed into conflict and chaos. Likewise, if Sayf al-Dawlah had not returned from Martyropolis and defeated the rebels once and for all, it is impossible to know what sort of state Dizbar and Ibn al-Ahwāzī would have constructed in Antioch. Similarly, if Sayf al-Dawlah or his son had been able to establish a firmer control over Antioch, the powerful imperial army might never have captured it. These differences in power show that the disasters in Antioch in the late 960s cannot be simplistically blamed on the refugees, and they can perhaps be lost if we focus exclusively on the “throwntogetherness” of different individuals and groups.50

Ultimately, historians should not blame the refugees for the tenth-century uprising and its aftermath any more than we would blame refugees for conflict in their host countries today. The way we speak about the past shapes the way we view similar situations in the present, and what we know about present events should help us to reconsider the way we speak about the past. Though the refugees from Tarsus certainly had a role in the Antiochian revolt, even providing its first leader, the crisis was also a convenient pretext that was seized upon by longtime residents of Antioch like Ibn al-Ahwāzī, not to mention manipulated by much larger imperial powers such as the Byzantines. In the case of medieval Antioch, it seems that most premodern historians and other commentators were able to avoid vilifying the refugees en masse for the tragedies that occurred, and we must be careful to follow this element of their example in the present. Only by walking the thin lines that respect the humanity and dignity of refugees can we hope to minimize the suffering, and even “martyrdom,” so vividly described by Ibn Kathīr.

References

Anṭākī, Yaḥyá ibn Sa‘īd ibn Yaḥyá al-. “Histoire de Yahya-Ibn-Sa‘ïd d’Antioche, continuateur de Sa‘ïd-Ibn-Bitriq.” Edited and translated by I. Kratchkovsky and A. Vasiliev. Patrologia orientalis 18, no. 5 (1957), 699-833.

‘Aẓīmī al-Ḥalabī, Muḥammad ibn ‘Alī al-. Tārīkh Ḥalab. Edited by Ibrāhīm Za‘rūr. Damascus, 1984.

Bar ‘Ebrāyā. The Chronography of Gregory Abû’l Faraj, the Son of Aaron, the Hebrew Physician, Commonly Known as Bar Hebraeus: Being the First Part of His Political History of the World. Translated by Ernest A. Wallis Budge. 2 vols. London: Oxford University Press, 1932.

Bosworth, C. Edmund. “The City of Tarsus and the Arab-Byzantine Frontiers in Early and Middle ‘Abbāsid Times.” Oriens 33 (1992), 268-286.

Collyer, Michael. “Geographies of Forced Migration.” In The Oxford Handbook of Refugee and Forced Migration Studies, edited by Elena Fiddian-Qasmiyeh et al., 112-123. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, Elena, et al. “Introduction: Refugee and Forced Migration Studies in Transition.” In The Oxford Handbook of Refugee and Forced Migration Studies, edited by Elena Fiddian-Qasmiyeh et al., 1-19. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Ibn al-‘Adīm al-Ḥalabī al-Ḥanafī, Kamāl al-Dīn Abū al-Qāsim ‘Umar ibn Aḥmad ibn Hibat Allāh. Bughyat al-ṭalab fī tārīkh Ḥalab. Edited by Suhayl Zakkār. 12 vols. Beirut: Dār al-Fikr, 1988.

———. Zubdat al-ḥalab min tārīkh Ḥalab. Edited by Khalīl al-Manṣūr. Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-‘Ilmīyah, 1996.

Ibn al-Athīr. Al-Kāmil fī al-tārīkh. Edited by Muḥammad Yūsuf al-Daqqāq. Vol. 7. Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-‘Ilmīyah, 1987.

Ibn Kathīr. Al-Bidāyah wa-al-nihāyah. Vol. 11. Beirut: Maktabat al-Ma‘ārif, 1991.

Leo the Deacon. Leonis diaconi Caloënsis Historiae libri decem. Edited and translated by Charles Benoît Hase. Bonn: Ed. Weber, 1828.

———. The History of Leo the Deacon: Byzantine Military Expansion in the Tenth Century. Translated by Alice-Mary Talbot and Denis F. Sullivan. Washington: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2005.

Lischer, Sarah Kenyon. “Causes and Consequences of Conflict-Induced Displacement.” Civil Wars 9: 2 (June 2007), 142-155.

Massey, Doreen. For Space. London: SAGE Publications, 2005.

Miskawayh. The Concluding Portion of The Experiences of the Nations. Vol. 2 and 5 of The Eclipse of the ‘Abbasid Caliphate: Original Chronicles of the Fourth Islamic Century, edited and translated by H.F. Amedroz and D.S. Margoliouth. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1921.

Muqaddasī, al-. Aḥsan al-taqāsīm fī ma‘rifat al-aqālīm. Edited by M.J. de Goeje. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1906.

———. The Best Divisions for Knowledge of the Regions. Translated by Basil Anthony Collins. Reading: Garnet Publishing Limited, 1994.

Salehyan, Idean, and Kristian Skrede Gleditsch. “Refugees and the Spread of Civil War.” International Organization 60: 2 (Spring 2006), 335-366.

Yāqūt ibn ‘Abd Allāh al-Ḥamawī al-Rūmī al-Baghdādī, Shihāb al-Dīn Abū ‘Abd Allāh. Mu‘jam al-buldān. Vol. 4. Beirut: Dār Ṣādir, 1993.

Zayat, Habib. “Vie du patriarche melkite d’Antioche Christophore (†967) par le protospathaire Ibrahim ibn Yuhanna: Document inédit du Xe siècle.” Proche-Orient chrétien 2 (1952): 11-38, 333-366.

Notes

- Sarah Kenyon Lischer, “Causes and Consequences of Conflict-Induced Displacement,” Civil Wars 9: 2 (June 2007), 145. ↑

- Idean Salehyan and Kristian Skrede Gleditsch, “Refugees and the Spread of Civil War,” International Organization 60: 2 (Spring 2006), 339-341. ↑

- Michael Collyer, “Geographies of Forced Migration,” in The Oxford Handbook of Refugee and Forced Migration Studies, ed. Elena Fiddian-Qasmiyeh et al. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 118-119. ↑

- Salehyan and Gleditsch, “Refugees,” 361. ↑

- Salehyan and Gleditsch, “Refugees,” 360. ↑

- Elena Fiddian-Qasmiyeh et al., “Introduction: Refugee and Forced Migration Studies in Transition,” in The Oxford Handbook of Refugee and Forced Migration Studies, ed. Elena Fiddian-Qasmiyeh et al. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 4-6. ↑

- Doreen Massey, For Space (London: SAGE Publications, 2005), 151. ↑

- Yaḥyá ibn Sa‘īd ibn Yaḥyá al-Anṭākī, “Histoire de Yahya-Ibn-Sa‘ïd d’Antioche, continuateur de Sa‘ïd-Ibn-Bitriq,” ed. and trans. I. Kratchkovsky and A. Vasiliev, Patrologia orientalis 18: 5 (1957), 784. ↑

- Miskawayh, The Concluding Portion of The Experiences of the Nations, ed. and trans. H.F. Amedroz and D.S. Margoliouth (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1921), 5:208; Ibn al-Athīr, al-Kāmil fī al-tārīkh, ed. Muḥammad Yūsuf al-Daqqāq (Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-‘Ilmīyah, 1987), 7: 273; Habib Zayat, “Vie du patriarche melkite d’Antioche Christophore (†967) par le protospathaire Ibrahim ibn Yuhanna: Document inédit du Xe siècle,” Proche-Orient chrétien 2 (1952), 333; Shihāb al-Dīn Abū ‘Abd Allāh Yāqūt ibn ‘Abd Allāh al-Ḥamawī al-Rūmī al-Baghdādī, Mu‘jam al-buldān (Beirut: Dār Ṣādir, 1993), 4: 28. ↑

- Kamāl al-Dīn Abū al-Qāsim ‘Umar ibn Aḥmad ibn Abī Jarādah ibn al-‘Adīm, Bughyat al-ṭalab fī tārīkh Ḥalab, ed. Suhayl Zakkār (Beirut: Dār al-Fikr, 1988), 8: 3656. ↑

- Miskawayh, Experiences, 5: 224. ↑

- Bar ‘Ebrāyā, The Chronography of Gregory Abû’l Faraj, the Son of Aaron, the Hebrew Physician, Commonly Known as Bar Hebraeus: Being the First Part of His Political History of the World, trans. Ernest A. Wallis Budge (London: Oxford University Press, 1932), 1: 170. ↑

- Yāqūt, Muʻjam, 4:28-29. Ibn al-‘Adīm echoes this story, but instead of banners he has Nikephoros set up two spears—one with a copy of the Qur’an on top and the other with a cross—and he does not include the speech about the advantages of Christian rule and the evils of Islam; see Kamāl al-Dīn Abū al-Qāsim ‘Umar ibn Aḥmad ibn Hibat Allāh ibn al-‘Adīm al-Ḥalabī al-Ḥanafī, Zubdat al-ḥalab min tārīkh Ḥalab, ed. Khalīl al-Manṣūr (Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-‘Ilmiyya, 1996), 84. ↑

- Ibn al-ʻAdīm, Zubdat, 84. The tenth-century geographer al-Muqaddasī tells us that many moved to Banias in the Golan Heights as well; see al-Muqaddasī, The Best Divisions for Knowledge of the Regions, trans. Basil Anthony Collins (Reading: Garnet Publishing Limited, 1994), 147. ↑

- Ibn Kathīr, al-Bidāyah wa-al-nihāyah (Beirut: Maktabat al-Ma‘ārif, 1991), 11: 255. ↑

- Leo the Deacon, The History of Leo the Deacon: Byzantine Military Expansion in the Tenth Century, trans. Alice-Mary Talbot and Denis F. Sullivan (Washington: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2005), 108-109. ↑

- Yāqūt, Muʻjam, 4: 29. ↑

- Ibn al-ʻAdīm, Zubdat, 84. ↑

- Ibn al-ʻAdīm, Zubdat, 84. ↑

- Yāqūt, Muʻjam, 4: 28. ↑

- Bar ʻEbrāyā, Chronography, 1: 171. ↑

- Zayat, Vie, 333. ↑

- Zayat, Vie, 335. ↑

- Zayat, Vie, 335. ↑

- This term is transliterated from Greek in the Arabic text. ↑

- Zayat, Vie, 335. ↑

- Some of the names involved in these events have uncertain spelling and pronunciation. They may be spelled differently in some sources. Ibn Kathīr (1991, 11:255), strangely, claims that Dizbar was “from the Romans” (i.e. the Byzantines), but all the other sources agree that he was from Daylam. ↑

- Ibn al-ʻAdīm, Bughyat, 8: 3657. ↑

- Ibn al-ʻAdīm, Bughyat, 8: 3658. ↑

- Ibn Kathīr, Bidāyah, 11: 255. ↑

- Ibn al-ʻAdīm, Zubdat, 88. ↑

- Anṭākī, “Histoire,” 798. ↑

- Zayat, Vie, 355; Anṭākī, “Histoire,” 822. ↑

- Ibn al-Athīr, Kāmil, 7: 318; Bar ʻEbrāyā, Chronography, 1: 173. ↑

- Zayat, Vie, 335. ↑

- Ibn Kathīr, a committed Sunnī, blames the influence and leadership of the Shī‘īs (such as Sayf al-Dawlah) for many Islamic tragedies, including the conquest of Antioch; see Ibn Kathīr, Bidāyah, 11: 267. ↑

- Massey, Space, 151. ↑

- The reference to mills is found in Ibn al-Athīr (Kāmil, 7: 288), Ibn al-‘Adīm (Bughyat, 8: 3657), and Ibn Kathīr (Bidāyah, 11: 255). Miskawayh (Experiences, 5: 226) says that he supervised the “walls” of Antioch (and D.S. Margoliouth translates this as “farmed the environs of Antioch,” though I am not sure how she reached this interpretation), but this is likely a mistake in transmission, as the words arḥā’ (mills) and arjā’ (walls) are distinguished by only one dot in Arabic. Even the edited text of Ibn al-‘Adīm says both arḥā’ and arjā’ within the same sentence. Ibn Kathīr clarifies the issue by using a different word for “mills,” ṭawāḥīn. Ibn al-‘Adīm (Zubdat, 86; Bughyat, 8: 3658) also claims that he was in charge of the agricultural proceeds (mustaghallāt) of the city, so “mills” seems a more likely reading than “walls.” ↑

- Miskawayh, Experiences, 5: 226; Ibn al-ʻAdīm, Bughyat, 8: 3657. ↑

- Ibn al-ʻAdīm, Zubdat, 87; Ibn al-ʻAdīm, Bughyat, 8: 3658. ↑

- Zayat, Vie, 335-337. This passage is mostly missing from the manuscript of the Life of Christopher translated by Zayat in 1952, and parts of it are moved to a different location in the text, placed at the beginning of the rebellion. I am providing my own translation, which incorporates the other extant manuscript of the text. My full translation of the Life is under consideration for publication and is included as an appendix to my dissertation. ↑

- Ibn Kathīr, Bidāyah, 11: 255. ↑

- Zayat, Vie, 337; Anṭākī, “Histoire,” 798. ↑

- Miskawayh, Experiences, 5: 227. ↑

- Ibn Kathīr, Bidāyah, 11: 255. ↑

- Remember that several sources do, in fact, blame newly arrived refugees for the fall of Antioch in 969, describing the treachery of the Christians of the fortress of Lūqā. Even in this part of the story, there is divergence, as Ibn al-Athīr’s (Kāmil, 7: 318) version is much more polemically anti-Christian than that of the Christian writer Bar ‘Ebrāyā (Chronography, 1:173). ↑

- Zayat, Vie, 337. ↑

- Salehyan and Gleditsch, “Refugees,” 342-344. ↑

- Massey, Space, 10. ↑

- Massey, Space, 151. ↑

Memories of Migrations

Refugees in Medieval Antioch

وكان أهل طرسوس والمصيصة قد أصابهم قبل ذلك بلاء وغلاء عظيم، ووباء شديد، بحيث كان يموت منهم في اليوم

الواحد ثمانمائة نفر، ثم دهمهم هذا الأمر الشديد فانتقلوا من شهادة إلى شهاد أعظم منها.

The people of Tarsus and Mopsuestia had already been wounded by great affliction, hyperinflation, and intense disease, to the point that 800 of them were dying every day. Then this harsh command came upon them suddenly, and so they were carried from one martyrdom to an even greater martyrdom.

—Ibn Kathīr (d. 1373), al-Bidāyah wa-al-nihāyah

On August 16, 965, the citizens of Tarsus surrendered to the army of Emperor Nikephoros II (r. 963-969) and the city became a Roman/Byzantine possession for the first time in over a century. In exchange for the peaceful surrender of the city, its Muslim residents were allowed to take what they could carry and move to Antioch and other locations that were still in Muslim-ruled territory. By the end of the year, Antioch was in open rebellion against its ruler, the emir of Aleppo, and in 969 it too fell to the advancing Byzantines. Were the refugees from Tarsus to blame for this political chaos and collapse? Several of them were at the head of the rebellion, and—then as now—there must have been angry residents ready to blame them for all the ensuing disasters. Even an otherwise careful scholar might be tempted to describe the conflict as a result of the influx of refugees, not to mention someone seeking to use the past for their exclusionary present purposes. Yet a closer reading of the sources shows that the ambitions of imperial powers and elite Antiochians were more to blame than the refugees from Tarsus. Here I argue that historians must treat past refugees with the sort of understanding that is necessary in our interactions with present refugees, neither stripping them of all agency nor blaming them for negative outcomes over which they had no control.

Theoretical Foundations

Within the broader field of migration studies, forced migration studies has come to prominence in recent decades, spurred by major refugee crises that in some cases continue today. Forced migration can be caused by such issues as environmental change and crisis, human trafficking, religious persecution and other human rights violations, and violent conflict, the last of which is the most relevant category for my discussion here. Violent conflict itself has been disaggregated into a number of subcategories by Sarah Kenyon Lischer: “international conflict” includes border wars, third party (or “multilateral”) intervention, and invasion, while “civil conflict” includes civil war, genocide, failed states, and persecution.1 Each type of conflict has unique characteristics that can be analyzed productively and applied to a historical circumstance such as the conflicts in Cilicia and Syria in the 960s, while the historical data can also be used to critique our assumptions about the content of the categories. Naturally, conflict in the tenth century may differ from contermporary ones, and caution must be exercised in applying modern categories to map violent struggles of the distant past.

Nevertheless, if I were to categorize the conflicts under discussion here, I would argue that the conflict began with an invasion of Cilicia (including Tarsus) by the Byzantine army, producing a major forced migration, then was followed by a civil war within the territory of northern Syria ruled by the Ḥamdānid emir Sayf al-Dawlah (r. 945-967), even approaching the characteristics of a failed state. However, these internal conflicts and crises do not seem to have caused a migration crisis on any level approaching that caused by the Byzantine invasion, pointing to the power of the imperial authorities in commanding and effecting migration to a far greater extent than occurs “organically” in internal conflicts. Meanwhile the invasion continued apace, with Antioch too falling four years after Tarsus. The Byzantines were certainly interested in seizing territory and reshaping its population, but in the end, they maintained the Ḥamdānid government as a client state in Aleppo rather than overthrowing it entirely.

Figure 1: Map of Ḥamdānid territory in approximately 955. © Ro4444 / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0

Idean Salehyan and Kristian Skrede Gleditsch have written on the need to view forced migration and conflict within a context large enough that it is not bound by the recognized borders of nation-states, as the movement of large groups of refugees can create social networks that cross borders.2 This is especially important when we examine a period in which “nation-states” as we know them did not exist, when borders were not always precisely defined and changed more commonly than they do today. After all, states themselves, even today, are constructed and historically contingent.3 An empire establishing and defending its borders and collecting taxes is involved in the ongoing process of constructing its own state, and when rebels attempt to overthrow their ruler and establish themselves independently they are seeking to do the same.

Salehyan and Gleditsch also discuss the potential for refugee movements to spread conflict across borders, a phenomenon that seems to be in evidence in the 965 rebellion in Antioch. They emphasize, however, that “most cases of refugee flows do not lead to violence” and that “there is clearly no reason to expect deterministic links between refugees and conflict.”4 The events of the 960s provide an opportunity to test their theses on the relationship of refugees and conflict, lending further weight to the argument that the arrival of refugees in Antioch was not the cause of the rebellion and ensuing civil war, even if it may have been exploited by local and governmental actors with their own interests. Even if “refugees from neighboring countries can increase the risk of intrastate conflict,” this does not mean that the refugees are the cause of such conflict, though anti-refugee political actors often seek to blame them for it.5

More broadly, this points to one of the key questions in forced migration studies, the question of refugees’ agency. It is important not to overlook the role of refugees and other migrants in determining their own future, though it can often be tempting to conceptualize them as pawns at the mercy of more powerful forces.6 Terms such as “forced” migration can unfortunately contribute to the assumption that migrants are powerless, and it is important to recognize the choices that they make in the face of difficult circumstances. On the other hand, in situations where civil conflict follows upon the arrival of refugees, an excessive emphasis on the choices made by the refugees can lead observers to blame them for the suffering and chaos that ensues. Even as we recognize the agency of refugees, we must not make them responsible for everything that happens around them, keeping in mind that there are far more powerful actors with a role to play as well. The refugees who arrived in Antioch sparked difficult discussions there, to be sure, but the inhabitants of the city could have made different decisions when faced with this “inevitable contingency,” to use Doreen Massey’s terminology, referring to the unexpected juxtaposition of locals with new arrivals that may spark antagonism, and “is revealed in particular fractures which pose the question of the political.”7 In sum, Northern Syria was not fated to be consumed by conflict when the refugees arrived. Let us turn now to examine the processes by which the region was reshaped in this time of often violent encounter.

The Story: A First Look

I will begin with a summary of the story in order to introduce the key characters and events and show how a cursory reading might be used to demonize the Tarsian refugees as the cause of the Antiochian rebellion and the ensuing warfare and chaos. Muḥammad ibn al-Zayyāt was the governor of Tarsus appointed by Sayf al-Dawlah, but the Byzantine armies were approaching. Both before and during his reign as emperor, Nikephoros II Phōkas was renowned for his Muslim conquests. In 962, he came for Cilicia and Syria, and he took Anazarbus (‘Ayn Zarbah), northeast of Tarsus, with little opposition, massacring many of its inhabitants despite an earlier promise of safety. Yaḥyā ibn Sa‘īd Al-Anṭākī (11th century) notes that many of the survivors made their way to Tarsus, providing another layer to the issue of refugees and conflict.8 Ibn al-Zayyāt, no longer convinced that loyalty to Sayf al-Dawlah could ensure the safety of himself and his city, ordered the local preachers not to mention the emir’s name in their Friday sermons—a traditional way of demonstrating a change in political allegiance—and led an army to fight Nikephoros outside the city. The loyalty of Tarsus was thus already suspect.

Ibn al-Zayyāt’s army was decimated by the Byzantines, and even the governor’s own brother died in the battle. Though Tarsus itself was not attacked, the people turned against their governor, returned Sayf al-Dawlah’s name to the sermons, and sent him a message declaring their renewed loyalty. At this point, the sources diverge somewhat regarding the fate of the governor. Miskawayh (d. 1030) and Ibn al-Athīr (d. 1233) claim that Ibn al-Zayyāt committed suicide by jumping into the river from the balcony of his waterfront house, with the implication that this occurred in 962 or shortly thereafter, but Ibrāhīm ibn Yaḥyā (10th-11th century) and Yāqūt al-Rūmī (d. 1229) claim that he was still alive and played a role in the surrender of Tarsus three years later.9 Ibn al-‘Adīm (d. 1262) insists that Ibn al-Zayyāt was no longer in power and that control of the city had passed to his subordinate Rashīq al-Nasīmī, a favorite among the people of Tarsus and an ostensible ally of Sayf al-Dawlah, some time before the conquest.10 The claims are ultimately irreconcilable.

In any case, the sights of the Byzantines were set on Cilicia again three years later, specifically on Mopsuestia (al-Maṣṣīṣah) and Tarsus, after an unsuccessful 964 attack on Mopsuestia. Even before the summer 965 season of hospitable weather and warfare began, the rulers of these cities had sent a messenger to Nikephoros (now emperor) at his winter retreat in Caesarea, seeking an arrangement by which they could pay tribute and align themselves with imperial power. The Ḥamdānid loyalty of the border cities was hanging by a thread. Nikephoros was initially open to such an arrangement, but when he heard how bad the situation was in Cilicia—where the people of Tarsus were so hungry that they were eating dogs and carrion—he was furious that they were seemingly taking advantage of his generosity. He placed the letter on the messenger’s face and set it on fire, burning the messenger’s beard, and compared the Cilicians to a hibernating snake that would eventually wake up and bite him if he did not attack them and put them in their place. Finally, he told the messenger to warn Mopsuestia and Tarsus that he had “nothing but the sword” for them, and he set out for war.11

The emperor first conquered and devastated Mopsuestia, slaughtering many of its inhabitants, but when he reached Tarsus he had a change of heart— the Christian polymath Bar ‘Ebrāyā (d. 1286) claims that when he heard the groans of its suffering people, his heart was grieved—and accepted the people’s pleas for a peaceful surrender.12 He treated its people well and honored its leading men at his own table, but ordered that its Muslim inhabitants must either vacate the city, convert to Christianity, or submit to his rule and pay a special tax. Yāqūt, quoting an eleventh-century source who had personally interviewed some of the refugees, presents a dramatic scene in which Nikephoros set up two banners and offered the people of Tarsus a choice between the good governance of his Christian empire and the sinful, unjust realm of the Muslims.13 Most of the Muslims of Tarsus chose to leave—Ibn al-‘Adīm says as many as 100,000, though such numbers are difficult to verify—and the bulk of these migrants ended up in Antioch.14 Their condition was bleak, having survived the ravages of intense famine, hyperinflation, and plague, and Ibn Kathīr says that Nikephoros’s resettlement order “came upon them suddenly, and so they were carried from one martyrdom to an even greater martyrdom.”15

Figure 2: Battle between Byzantine and Arab armies in Cilicia, 950. National Library of Spain VITR/26/2, fol. 136v

There is general agreement among the sources that Nikephoros was surprisingly kind to the refugees, providing a military escort to ensure their safe arrival in Antioch (well over 100 miles away) and ships if they wished to go elsewhere. They were allowed to bring some of their possessions as well, though there is some disagreement here: most sources agree that they could take as much as they could transport, but Leo the Deacon (10th century) claims that they were allowed to take “their own bodies and only the necessary clothing,” perhaps exaggerating their destitution in order to emphasize the power of the emperor and the suffering of the enemy.16 Yāqūt adds that they had to pay the Byzantines for means of transportation for their goods and that the Byzantines charged exorbitant prices, about a third of each person’s possessions.17 More importantly for our discussion of the ensuing rebellion, most sources agree that the refugees were allowed to take their weapons with them. Ibn al-‘Adīm claims the opposite, but this may be a mistaken claim on his part or an error in transmission, because the other sources unanimously declare that the refugees arrived in Antioch fully armed.18

Nikephoros, it seems, was fully aware of the significance of conquering Tarsus, which had long been a base for raids on Byzantine territory and thus had an unusually large population of military personnel. According to Ibn al-‘Adīm, the emperor climbed the pulpit of the main Friday mosque and asked the soldiers around him, “Where am I?” When they responded that he was on the pulpit of Tarsus, he answered, “No! Rather, I am on the pulpit of Jerusalem, for this [city] was keeping you from that one.”19 Most sources report that the emperor then converted the Friday mosque into a stable and burned its pulpit, while Yāqūt claims that he destroyed all the mosques and burned the city’s Qur’ans.20 He refortified the city and its economy improved enough that many natives returned in the coming years. Some converted to Christianity, though others remained Muslims and paid a special tax. Bar ‘Ebrāyā adds, however, that all children in Byzantine Tarsus were baptized, whether their parents were officially Christian or not.21

Sayf al-Dawlah, meanwhile, was suffering from chronic paralysis and attempting to recover in far-off Martyropolis (Mayyāfāriqīn), his second capital, and the people of Cilicia and Syria were growing more and more impatient with his inability to protect them from the invaders.

The people of Antioch were suddenly faced with the arrival of many thousands of armed refugees, bearing news of the power and looming threat of the Byzantine army. The governor of Antioch, named Fatḥ, was overwhelmed. Ibrāhīm reports that the Antiochians asked the newly arrived Ibn al-Zayyāt, who he believes was still alive (perhaps confusing him with Fatḥ), to take control of their city and keep things from falling apart any further.22 However, he adds that Ibn al-Zayyāt was so afraid of Nikephoros that he refused.

In any case, neither Fatḥ nor Ibn al-Zayyāt remained in power, and the Antiochians chose Rashīq, another new arrival, to replace their previous leaders. Ibrāhīm tells us that Rashīq’s main advice to the Antiochians was to surrender to Nikephoros and make a deal with him, no doubt informed by his recent experience in Tarsus.23 He argued “that this was the way of prosperity and that they would never attain the perfect calm and tranquility that they desired if they did not obey” the emperor.24 When they sent emissaries to Nikephoros, however, he was not receptive to their pledges of loyalty and offers of money, responding:

As for money, I do not accept it because the king of the Romans has no need of it, and because the Muslims might give it today and refuse it tomorrow. Nor do I accept pledges, because while they have meaning for some people, most do not even think about them. I only request one thing, whenever you wish and whenever you realize that it is an easy and insignificant thing for you to fulfill. That is, I wish to build a fortress on a rock formation within your city, in which I will have a general [stratēgós]25 and a small number of others to defend you, and by means of them I will conquer.26

The Antiochians refused to allow this imperial intrusion into their local autonomy and rejected the offer. Rashīq was ashamed by the failure of his diplomatic strategy, and as he felt “useless,” he decided to try a different approach: armed revolt against Sayf al-Dawlah. He quickly removed the emir’s name from the Friday sermons and had a letter read publicly that purported to be from the ‘Abbāsid caliph in Baghdad, authorizing him to rule the area.

Rashīq was joined by al-Ḥasan ibn al-Ahwāzī, a wealthy Antiochian, and they assembled an army to move on Aleppo. A band of soldiers were there from Daylam, in northern Iran, and they submitted to Rashīq along with their leader, Dizbar al-Daylamī.27 The bulk of the city surrendered quickly, but Sayf al-Dawlah’s representative Qarghuwayh was able to barricade himself within the nearly unassailable hilltop citadel, which therefore remained in loyalist hands, just as it had during a Byzantine invasion in 962. Rashīq and his allies laid siege to the citadel of Aleppo for three months and ten days, with heavy fighting between the factions on a daily basis. Eventually, after Sayf al-Dawlah sent reinforcements led by a Black servant named Bishārah, Rashīq fell from his horse during a battle and was killed. Ibn al-‘Adīm tells us that the killer was Abū (or Ibn) Yazīd al-Shaybānī, a soldier of Sayf al-Dawlah who had previously made an alliance with Rashīq, and that Abū Yazīd cut off Rashīq’s head and brought it triumphantly to Qarghuwayh.28 Other accounts vary in details, but all agree that Rashīq died in battle and his allies retreated to Antioch. Ibn al-‘Adīm says that Rashīq’s death was “lamented.”29

Back at their starting point, the rebels regrouped. Dizbar was named emir and took control of the movement, with Ibn al-Ahwāzī remaining as vizier, and a descendant of the Prophet named Abū al-Qāsim al-Afṭasī was brought on board as “caliph” to provide religious legitimacy.30 Qarghuwayh and the loyalist forces hoped to press their advantage and moved quickly toward Antioch, where they were defeated and repelled after some initial successes. The rebels fought their way to Aleppo once again, and Ibn al-‘Adīm claims that they were able to capture the entire city, including the citadel, in April or May of 966.31 He adds that they began to set up the bureaucracy of their nascent state, appointing judges and other governmental officers, and collected taxes from cities throughout the region. Most sources do not say that Aleppo fell, however, and al-Anṭākī in particular states that the rebels were repulsed from Aleppo as they had been before.32 Whatever the case, around this time Sayf al-Dawlah was finally feeling well enough to make the journey from Martyropolis, and he came with his armies to put down the rebellion once and for all. He captured Dizbar and executed him immediately, and though Ibn al-Ahwāzī had hidden himself with a local tribe, a ransom secured his delivery to the emir. Sayf al-Dawlah put him in prison temporarily, but when the Byzantines began to advance again, the emir did not want the prisoner to distract him from the war effort, so he had him executed as well.

Despite the return of Sayf al-Dawlah, things continued to be chaotic and unstable, especially in Antioch. In fact, the emir died in 967—at which point some resentful Antiochians assassinated Christopher, the Christian patriarch, who had remained loyal to Sayf al-Dawlah throughout the rebellion and its aftermath—and his son Sa‘d al-Dawlah (r. 967-991) found it difficult to secure his rule. Qarghuwayh established himself as the largely autonomous ruler of Aleppo, while control of Antioch bounced rapidly from its Ḥamdānid-appointed governor Taqī al-Dīn, to Muḥammad ibn ‘Īsَā and his group of Khurāsānī soldiers, to a Kurd named ‘Allūsh, to a black man named al-Rughaylī. This final leader, as Ibrāhīm and al-Anṭākī tell us, had actually been a refugee from Tarsus himself, at first fleeing to Egypt, then returning to Antioch with a group of soldiers to fight the Byzantines, and eventually taking control of the entire city by assassinating ‘Allūsh in his own court.33

Finally, the Byzantines conquered the collapsing city from al-Rughaylī on October 28, 969. Ibn al-Athīr and Bar ‘Ebrāyā tell us that they were aided by the inhabitants of the fortress of Lūqā, which they had also recently captured.34 The people of Lūqā, who were Christians, made an agreement with the conquerors and fled as refugees to Antioch, but then betrayed and overthrew the city from within, providing secret information to the Byzantine army. Once again, it seems that refugees were at the heart of the fall of Antioch, easily blamed for its misfortunes. The city remained in Byzantine hands (despite several rebellions and other displays of anti-imperial sentiment) until 1084.

Another Reading

Ibn al-‘Adīm’s Bughyat al-ṭalab (1988, 8:3656) is the only text to describe the journey of the Tarsians to Antioch using the verb iltaja’a or “seek refuge,” which is related to lāji’, the standard term for “refugee.” They were forced from their homes by an invading power and likely stripped of many of their possessions, especially their houses and other immovable goods. They had the option to convert to Christianity or pay a special tax—similar to the jizya assessed on religious minorities in Muslim-ruled territories—but most decided that flight was the best available option.

This created a refugee crisis in Antioch, where many thousands of new residents were arriving simultaneously, telling tales of the powerful invading army they had left behind. The Antiochians must have hoped that they could reach an agreement with Nikephoros like the one reached in Tarsus, as opposed to the situation in Mopsuestia where massive numbers had been massacred. They turned to those who had the relevant experience—Ibrāhīm claims that Ibn al-Zayyāt was still alive and was asked first, but most sources simply say that the Antiochians chose Rashīq to be their leader. When negotiations with Nikephoros failed, Rashīq decided to “uncover his head” in rebellion, and the violence of invasion became the violence of civil war, to use Lischer’s categorization.35 Just as Salehyan and Gleditsch have described, a refugee crisis was followed by a spillover of violence into their new host country, and we are faced with a situation in which a refugee crisis was not merely the result of violence, but also a contributing factor in its spread.

There must have been plenty of Antiochians who opposed the idea of putting a newly arrived refugee in charge of their affairs, as well as those who blamed Rashīq when the negotiations fell through and the rebellion failed. Our own experience with refugee crises shows how quickly discourses of identity and place can be turned against newcomers, especially when conflict follows upon their arrival and outside threats exacerbate the stress of the situation. Throughout the story, “foreign” elements seem to be at the center of so many Antiochian tragedies: Ibn al-Zayyāt, Rashīq, and al-Rughaylī from Tarsus; Dizbar and his soldiers from Daylam; the Christian infiltrators from the fortress of Lūqā.36 Did the medieval historians blame the refugees for the ensuing disasters, and should we do so today? Was such civil conflict unavoidable?

First, it is important to recognize, following Massey, that none of this was inevitable, and that tenth-century Antioch, like all other places, was characterized by the “inevitable contingency” that poses “the question of the political.”37 The Tarsian refugees, including Rashīq, had considerable agency despite the constraints of their situation, as did the prior residents of Antioch. The Antiochians chose Rashīq as their new leader, and Ibrāhīm claims that their previous choice turned down the job out of fear of the Byzantines. They then chose, on Rashīq’s advice and in hope of peace and prosperity, to seek a diplomatic solution with Nikephoros, and when this fell through, it was Rashīq who chose what he thought was the best path forward for himself and his neighbors, rebellion against the Ḥamdānid government. Throughout this process, the sources describe little obvious tension between the refugees and the other Antiochians. Thus, when the people of Antioch—refugees and non-refugees—made the choice to rebel, they were simply choosing to engage in the process of forming a new state, since their current government did not seem to be able to provide the basic threshold of safety necessary for legitimacy, and the Byzantines did not accept their offer of tribute. Once the rebellion was suppressed, it became easier to view Sayf al-Dawlah as the legitimate ruler throughout the period, but this would by no means have been obvious to someone in the midst of the events. These challenges to the status quo reflect the agency of the people on a grand scale, though ultimately their attempt at state formation fell apart.

On the other hand, much more powerful actors were involved at the same time. Rashīq and the other refugees were making choices within the constraints presented to them, but in large part those constraints were constructed by powerful figures like Nikephoros. After all, though Rashīq chose—in consultation with the people of Antioch—to seek a negotiated settlement and to rebel when that settlement failed, it was Nikephoros who decided to reject the offer of the diplomats. The emperor did not directly bring about the Antiochian rebellion, but he played the most important role in constructing the conditions in which such a rebellion seemed an attractive option to the people of Antioch. Similarly, Sayf al-Dawlah’s choice—and the choice of rulers across the Islamic world—to send inadequate support to the Cilician/Syrian border meant that the Antiochians felt the Ḥamdānids could no longer provide for their safety. Their choice to rebel, in such a situation, is understandable, but it is also easy to see how it was shaped by larger forces.

In addition, the role of the non-refugee Antiochians should not be overlooked simply because Rashīq was the leading figure at the beginning of the rebellion, and a closer look at the medieval sources reveals that they do not fail to discuss other actors. Here the figure of Ibn al-Ahwāzī, the sole constant presence from the beginning of the rebellion to the end, deserves more attention than I have given him previously. His background and pre-rebellion career are somewhat unclear from the sources, but it seems most probable that he had been appointed as a government official supervising the mills and agricultural proceeds of Antioch.38 Whatever his position, he had access to enough money that he could essentially fund the rebellion independently—perhaps by taking advantage of funds that were supposed to be used for government projects, but also by calling in some loans and generally shaking down the Antiochian populace. Miskawayh calls him “a person of little rank” and Ibn al-‘Adīm calls him “disreputable.”39 Throughout the sources, no figure in this story is more negatively presented than Ibn al-Ahwāzī.

This “disreputable” man not only funded the rebellion, he played the biggest role in ensuring that it would take place. He encouraged Rashīq to rebel and told him that Sayf al-Dawlah’s illness made it impossible that he would ever return to Syria, a prediction that eventually proved unfounded. According to Ibn al-‘Adīm, Ibn al-Ahwāzī was the one who crafted the letter falsely claiming to be from the ‘Abbāsid caliph al-Muṭī‘ (r. 946-974), which gave Rashīq authority over the holdings of Sayf al-Dawlah and was read aloud from the pulpit of Antioch’s mosque at the beginning of the uprising.40 A similar letter was read in Aleppo when the rebels were in control of most of the city. Thus, though he largely worked behind the scenes, the rebellion would be almost unthinkable without the assistance and encouragement of Ibn al-Ahwāzī, apparently a native Antiochian—or at least, not a refugee from Tarsus.

Ibn al-Ahwāzī also had extensive control over the day-to-day operations of the rebels, serving as vizier and primary administrator although the official authority was in the hands of others. When Rashīq was killed and the rebels had to regroup in Antioch, Ibn al-Ahwāzī seems to have been the driving force behind the appointment of Dizbar and al-Afṭasī to leading roles in the movement. Ibrāhīm writes that despite their defeat and the death of their leader, all of them “remained firmly committed to their opposition and rebellion. The one who encouraged them in this was a person of Antioch named Ibn al-Ahwāzī, an intense, dynamic, and active person, and he had been the manager of their affairs in the time of Rashīq.”41 Upon Rashīq’s death, Ibn Kathīr says that Ibn al-Ahwāzī “became independent,” taking over leadership of the movement until Dizbar could be appointed, and he seems to have been the primary power behind the throne throughout the uprising.42

When he heard that Christopher had fled the city to avoid appearing to be a rebel sympathizer, Ibrāhīm and al-Anṭākī tell us that it was Ibn al-Ahwāzī who became furious and began to mistreat the Christians of Antioch in retribution.43 He arrested and otherwise harassed some of Christopher’s closest associates and sealed up the possessions of the Church in the patriarchal residence. Likewise, his designated “caliph,” al-Afṭasī (who was given the nickname al-Ustādh, “the Teacher”), is said to have oppressed the people of Antioch and inappropriately amassed wealth from them. Nevertheless, perhaps because of his relatively low profile, Miskawayh tells us that Ibn al-Ahwāzī still had enough support from “the people of the town” that together they were able to fight off Qarghuwayh’s offensive.44 This again shows the unity of those in Antioch, whether newly arrived refugees or longtime residents, in fighting off the emir of Aleppo and his loyalist army. Ibn al-Ahwāzī was, as Ibn Kathīr says, well established in Antioch.45

It is difficult to tell exactly why Ibn al-Ahwāzī played—and it seems did so deliberately—a behind-the-scenes role in the Antiochian rebellion. Perhaps he was used to the less public life of a government bureaucrat and wanted to find more charismatic leaders to serve as the faces of the uprising, or perhaps he thought he could avoid accountability if it failed. It is also possible that he wanted to find outsiders—first Rashīq, then Dizbar—to bear responsibility for his own risky undertaking. Whatever the reason, the medieval historians place most of the blame for the rebellion, and its failure, on Ibn al-Ahwāzī, and present him as essentially a moderately wealthy and corrupt Antiochian of middling social status who took advantage of the refugee crisis to provoke a rebellion by which he stood to gain much more wealth and prestige. It is notable that they all take this position rather than blaming the refugees, even when the rebellion was first led by one of the new arrivals.46 In fact, of all the people in Antioch, Patriarch Christopher is the only person who is explicitly said to have opposed the rebellion, though there must have been plenty of others. Even one of Christopher’s closest friends, a Christian leader named Theodoulos, came to the monastery to try to convince him to rethink his position and return to the city, but the patriarch stood firm.47

Conclusion