PDF

Download

Citations

Click and drag then release to select a passage to cite.

Annotations

How to submit annotations to Mizan Journal articles:

your work is published.

Search within

Farid al-Din Attar, the Man

Two Views

Image

Audio

Video

Chart or Graph

Farid al-Din Attar, the Man

Two Views

Part I. The Druggist of Nishapur

Farid al-Din Attar, a druggist living in the city of Nishapur, wrote a parable that has captivated readers and inspired artists for almost a thousand years. The Mantiq al-Tayr (Conference of the Birds) imagines a multitude of birds setting out on a quest to find the Simorgh, a divine raptorial bird in Iranian mythology. The birds traverse seven spiritual valleys: Quest, Love, Understanding, Independence and Detachment, Unity, Astonishment and Bewilderment, and Deprivation and Death. Only thirty birds survive the perils of the journey and achieve a vision of the Simorgh. But that vision turns out to be their own selves reflected in a heavenly mirror, for the name of the divine Simorgh also means “thirty birds” in Persian (si = thirty + morgh = bird).

In his sketch of Attar’s live in the Encyclopedia Iranica, B. Reinert tells us the following:

While ʿAṭṭār’s works say little else about his life, they tell us that he practiced the profession of pharmacy and personally attended to a very large number of customers . . . His placid existence as a pharmacist and a Sufi does not appear to have ever been interrupted by journeys. In his later years he lived a very retired life … He reached an age well over seventy … He died a violent death in the massacre which the Mongols inflicted on Nīšāpūr in April, 1221.1

A second work by Attar, Tadhkirat-i Awliya’, preserves capsule biographies of 72 earlier Sufis, many of them taken from Sufi works composed a century or more earlier by other Nishapur mystics. Though this attests to Attar’s depth of Sufi erudition, none of the mystics in the collection are named in Mantiq al-Tayr. Nor do the seven valleys correlate either with what the Sufis had written about stages a Sufi aspirant should pass through in order to become enlightened, or with the conception of a cosmic hierarchy of Sufi authority current in Attar’s era. According to this schema, a single Qutb occupied the highest place in the hierarchy, followed by three Nuqaba, then four Awtad, seven Abrar, 40 Abdal, and 300 Akhyar.

How, then, did the vision of the birds’ mystic journey arise, if not from a more general Sufi tradition? Being personally lacking in both spiritual insight and a deep knowledge of Sufi literature, the conclusions I shall put forward in this essay are based primarily upon my understanding of what the city of Nishapur was like during Attar’s lifetime.

My starting point is an assumption that Attar could not have envisioned the birds’ progression through the seven valleys if he had not, in some sense, already traversed them himself and experienced the theophany they finally attain to. If that is the case, however, how does a deep spiritual realization of Deprivation and Death square with his supposed “placid existence as a pharmacist and a Sufi”?

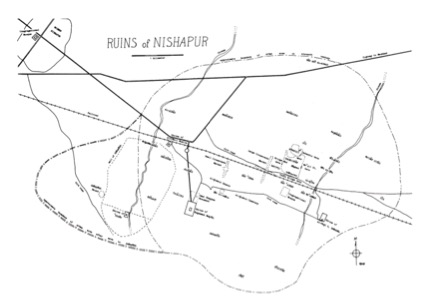

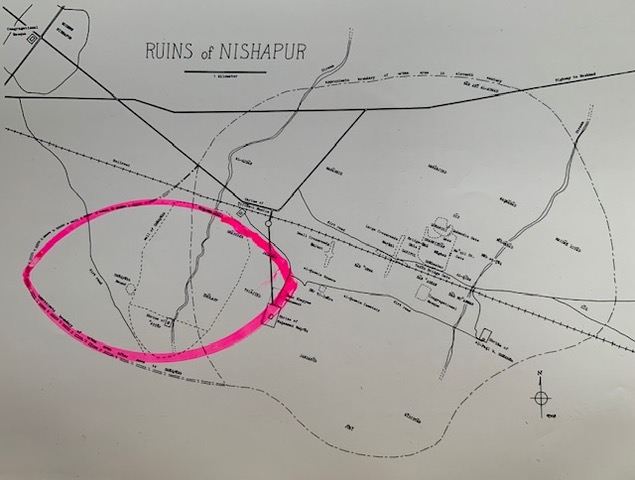

A map of Nishapur tells a sad tale. I drew in the 1960s after weeks of wandering through the field of buried ruins that is all that is left of the medieval city, and subsequently examining aerial photographs taken in the 1950s.

The circular area with the crossroads at the upper left demarcates the modern city’s built-up urban area at the time the photographs were taken. The population at that time was approximately 30,000. The stream that runs from north to south 2.5 kilometers east of the modern city bisects a walled area (dotted line) that, with its semicircular southern extension, is about twice the size of the 1950s city. The tomb of Attar, a lovely domed structure now surrounded by an extensive garden, is marked on the map at the center of the southern wall, above the semicircular extension. This location jibes with the tradition that Attar was killed at a ripe old age during the Mongol devastation of the city in 1221. The walls similarly support a tradition that the target of the Mongol attack was a region of the city named Shadyakh.

As for the larger city of which Shadyakh was a part, its extent is indicated by lighter of the two dashed lines that cuts through and vastly surpasses the Mongol era walls. Much of that area was doubtless taken up with gardens and orchards supplying the city’s markets; but my guess, based on the area within that line, is that Shadyakh was smaller than the large city by a factor of at least five. Thus if Shadyakh, being roughly the size of the modern city of the 1950s, had a population of similar size in Attar’s day, then the population of the larger metropolis, at its peak a century or so before Attar’s birth, should have been on the order of 200,000.

No wall encompassed the larger city. Hence, the perimeter I drew on the map derives from two sources: the aerial photographs of the ruins and ground observations that I made in 1966. Irrigation practices in the region draw water from aquifers that are tapped in the mountains north of the city and led to the city through underground channels called qanats. The gentle slope of these channels, as calculated by expert tunneling engineers, brings the water to the surface in the form of small streams, but qanats flowing beneath built-up areas could also be accessed through staircases. Temporary dams divert the steady flow of water that finally exits the qanat onto fields on either side. Low, closely spaced dikes follow the slope of the land so that the water irrigates the highest part of the field; and then, after a fixed amount of time, the dikes are opened so it irrigates the next highest diked area. And so it goes until all of the farmland is irrigated.

The lines of dikes show up on aerial photographs function exactly like contour lines on a map. In the completely flat landscape around Nishapur, they are normally parallel to one another and perpendicular to the direction of water flow. When the land surface is irregular, however, the hills and depressions that betray the presence of destroyed buildings fifteen feet or so underground cause the perpendicular lines to curve, and even form circles. The perimeter I have drawn on the map demarcates the limit of such hummocky land.

Figure 2. Aerial photograph of Nishapur ruins circa 1955. Note curved contour lines signaling hills and depressions.

My site observations that supplement this indicator of the extent of the ruins derive from the abundant traces of urban remains brought to the surface by yearly plowing, despite the many feet of wind-borne dust that have accumulated over the millennium since the population that dwelt in Nishapur during its heyday disappeared. I would pick a compass direction from a central point in the ruins and then count the number of paces from that point to the point where the myriad potsherds, glass shards, and brickbats no longer appeared underfoot.

I go into all this detail to assure the reader that the difference in area between the walled Shadyakh in which Attar lived his adult life and the enormous city that preceded it is not mere conjecture. Rather, it confirms the historical fact that Attar serviced his pharmacy customers clustered in a walled community surrounded by the deserted buildings of what had been, just a generation before, the largest and most important cultural center in Iran, if not in the entire Islamic world.

As an adult, Attar looked, on almost a daily basis, at streets bordered by crumbling houses, mosques with collapsed domes, and charred markets still littered with occupational bric-a-brac. Today’s news photos from war ravaged Syria and Afghanistan, or those from Beirut during its civil war in the 1980s, provide a good model for imagining the abandoned cityscape that lay outside the walls of Shadyakh.

But what about Attar in his childhood and teenaged years? Reports that he was in his seventies when the Mongols killed him have led scholars to suggest that he was born around 1145. If that is so, he was fifteen when a devastating earthquake rumbled through.2 And the following year saw the final abandonment of the main city. Yet natural catastrophe simply put the capstone on many years of strife and destruction.

The great city’s educated elite was riven by factional discord that intensified over the course of the eleventh century. The two factions were labeled Hanafi and Shafi‘i for the two preeminent schools of Islamic legal interpretation, but these names surely conceal social, economic, and political cleavages that are no longer recoverable. To skirt around these unknowable aspects of Nishapur’s civil war and focus on its destructive side, I will call the two factions the Pinks and the Greys.

In 1153, when Attar may have been eight years old, a group of Turkic nomads refused to obey the reigning Sultan’s demand for a tribute of 30,000 sheep. The Sultan responded militarily, but surprisingly, the nomads defeated his army and took him captive, leaving northeastern Iran undefended. The nomads proceeded to sack a number of cities. Two of Nishapur’s largest mosques were destroyed, and 15,000 male corpses were reportedly recovered from two city quarters. Women and children were carried off as slaves, and the nomads spent several days searching for loot. The walled Inner City, with a citadel on its northern edge (right hand side of Fig. 2), fended off the raiders. But they returned after sacking some smaller cities in the vicinity, and this time they overran and pillaged the Inner City as well. On the heels of this second attack, bandit gangs moved into the city to loot whatever the nomads had missed.

An officer of the Sultan named Ay Abah then asserted control over the city and continued as its overlord for twenty years, defending it from both nomads and rival commanders. But a famine that set in immediately after the nomad withdrawal stunted any quick recovery. A city the size of Nishapur depended on the regular arrival of thousands of camel loads of food and other necessities produced in outlying villages, but those villages had also suffered from the nomad rampage. In 1157 a report of skyrocketing prices indicates that rural food production was still lagging behind the city’s requirements.

Meanwhile, the rivalry between the Pinks and the Greys continued apace. In 1158, some Pinks killed a Grey, and the Grey leader demanded that the killers be turned over to him. The Pink leader refused. The Greys attacked, killed some Pinks, destroyed the Pink leader’s home, and burned out several streets, including the druggists’ market. Inasmuch as tradesmen in medieval Muslim cities normally clustered together to manufacture and sell their products, it is quite likely that Attar’s father lost his livelihood at this time. The fighting spread over the following months. Pink reinforcements came in from neighboring cities, and every night gangs of Pinks and Greys set fires in the quarters of their foes. Then the nomads attacked for a third time.

Attar probably witnessed all of this and experienced the loss of his father’s shop as a young teenager. But he would have been too young to take part in the fighting between the Pinks and the Greys that accelerated after a leading Grey was killed. The Pinks lost schools, mosques, and markets, and their leader fled the city. Within months, however, he returned in the company of the overlord Ay Abah. The revived Pinks took destructive revenge on the Greys, who seem to have retreated to the citadel. Ay Abah worked out a truce, but in 1161 the fighting resumed. A major Pink mosque was destroyed, along with its library, as were thirteen Pink and eight Grey schools that had survived the earlier rounds of pillaging. Precious collections of books were burned or sold off cheaply.

It was at this point that Ay Abah selected Shadyakh as the site for a new city. It was a spacious area on the western edge of the great metropolis that had benefited from two episodes of princely building projects in the ninth and eleventh centuries. Ay Abah, who had sponsored the Pink leader’s return to the city, saw to the rebuilding Shadyakh’s walls and moved there with his supporters, leaving the ruins to the Greys, who clustered in the Inner City and awaited Ay Abah’s attack. Holding Nishapur’s only high ground, the Greys mounted mangonels on the walls and cast stones onto any Pink targets they espied.

Ay Abah’s attack came in the middle of the year. During his two-month siege a stone from a mangonel killed the Pink leader. The citadel held out, only to surrender a few months later in 1162. The historian who recorded many of the details I have cited completed his chronicle some 40 years later, when eye-witnesses of Nishapur’s fall were still alive. He says of the abandoned metropolis:

“Where had been the assembly places of friendliness, the classes of knowledge, and the circles of scholars were now the grazing grounds of sheep and the lurking places of wild beasts and serpents.”3

If Attar was born in 1145, he had still not passed his twentieth birthday. Had he experienced the valley of Deprivation and Death? Most probably, along with everyone in his generation. But the Mantiq al-Tayr sees this valley as the ultimate stage of contacting the divine, not as a despairing depth of the sort that many refugees from war and devastation experience. So some sort of transformation takes place in Attar’s mind after 1162. He somehow re-experiences Deprivation and Death as the culminating stage of a sequence of feelings symbolized by the first six valleys.

Today’s widely recognized stages of grief — denial, numbness, and shock; bargaining; depression; anger; and acceptance — offer a suggestive comparison. The grief-stricken individual only perceives these stages in retrospect. Similarly, I would suggest, Attar’s transit through the seven valleys signals a deep, lengthy, and surprisingly positive period of meditation upon his unending experience of Nishapur’s destruction, analogous, I would suggest, to Sigmund Freud’s deep dive into the dreams of his childhood.

I estimate that 80 percent of the population permanently moved away, the ablest (or richest) of them resettling in the Arab lands and Anatolia to the west, or Afghanistan and India to the east. Though Nishapur’s ruins could have sheltered remnants of the population, without a robust and productive rural economy, rebuilding on a grand scale was impossible.4 Soon lists were being compiled to help pious pilgrims as they toured the ruins looking for the graves of famous saints and scholars. There were apparently no local residents left to help them. Unlike today’s survivors of urban destruction, however, who can realistically hope to see international reconstruction aid flowing to their city, there was no light at the end of Nishapur’s tunnel of horror. Shadyakh was destroyed, and Attar killed, in the Mongol invasion of 1221.

One must assume that Attar’s meditation on Nishapur’s fall was informed by an increasing understanding of Sufism. Yet Mantiq al-Tayr need not be read solely was a Sufi work. The word Sufi does not appear, nor does the name of any known Sufi. And most strikingly, for a branch of spirituality that was marked by individual verbal explosions expressing an ultimate experience of the divine — Ana al-Haqq (“I am the Truth”), or Ma fi hadhihi al-jubba illa Allah (“There is nothing in this shirt but God”) — it is a group rather than an individual that achieves contact with the divine in the seventh valley.

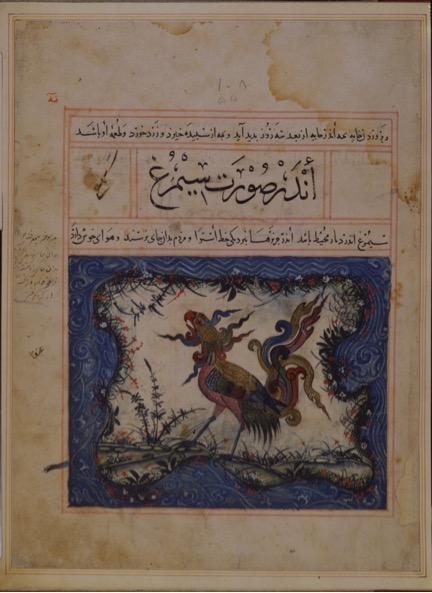

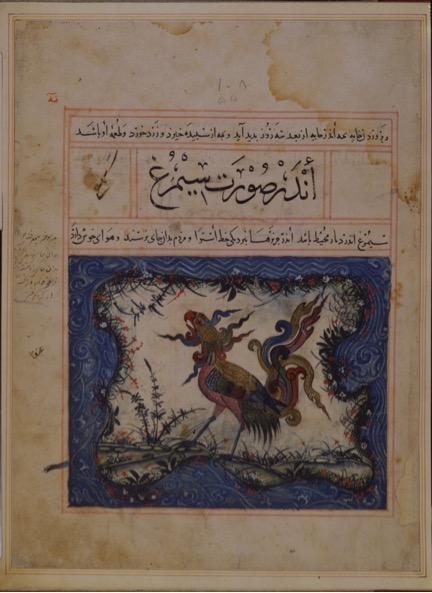

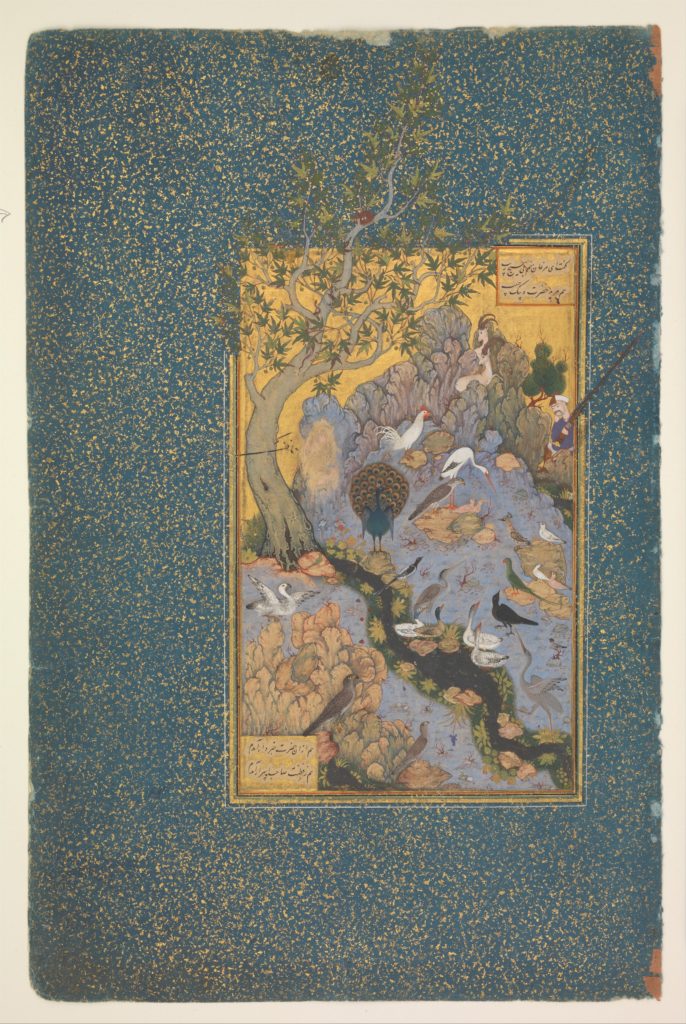

I know of no evidence that the Simorgh, a mythical raptorial bird, was ever understood to be a composite of “thirty birds” before Attar took it as his metaphor for the divine. Thirty, unlike seven or forty, was not a weighty symbolic number in the lands of Islam.5 To be sure, si meant thirty in Persian and Kurdish, but the syllable is not normally interpreted this way when it appears as a prefix in other Persian words. And I take it for granted that Attar never anticipated the crowded ornithological extravaganzas that Iranian miniaturists had begun to paint by the fifteenth century.

Figure 3. “The Simorḡ,” Marāḡa, 697 or 699/ca. 1297-1300, illustration from the Manāfeʿ-e ḥayawān. Courtesy of The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York, Ms. M. 500, fol. 55r.

So how did Attar hit upon this metaphor? I think again of Freud resorting to the myths of Oedipus and Electra to make his understanding of the unconscious palatable to an educated audience. I believe he was actually recreating the process that Attar went through. 1) Examine to the greatest depth one’s inner feelings. 2) Recognize that those feelings are not simply personal, but common to other people once they have carried out a similar self-examination. 3) Search the common store of myth and legend for tales that can symbolize the link between the mental condition of an individual and the mentality of humankind at large. 4) Set the metaphor free to be exploited and utilized by generations yet unborn.

If I put aside the purely Sufi interpretation of Attar’s parable, I can easily imagine that his thirty birds were actually human survivors of the fall of Nishapur. Perhaps Attar found exultation in his tracing of a spiritual path that could look upon Deprivation and Death and see not despair, but a point of contact with the divine, and he wanted to open his path to people he knew in Shadyakh as a way to helping them come to grips with the vanishing of their great metropolis. Thousands of birds begin the journey, but most of them fall away. Were those that persevered to the end, the thirty, actually fellow citizens of Attar who saw themselves, collectively, in the divine mirror as being at the culmination of their spiritual quest?

When in his career the druggist of Nishapur wrote Mantiq al-Tayr is unknown. Is it not possible, therefore, that he had not yet become a Sufi when he was struck by the magic of the Simorgh?

Part II. Nishapur

Farid al-Din Attar (1145?-1221) is both the best known and the least known Sufi from the city of Nishapur. He is the best known because Manteq al-Tayr (Conference of the Birds), a parable about the human quest for God, is one of the world’s most widely read and admired expressions of the Sufi vision and way. But he is the least known because so little information has been preserved regarding the details of his life. Writing in the Encyclopedia Iranica, B. Reinert tells us the following:

While ʿAṭṭār’s works say little else about his life, they tell us that he practiced the profession of pharmacy and personally attended to a very large number of customers … He evidently started writing certain books … while at work in the pharmacy … Anyway he was fortunate in not depending on his muse for his livelihood. He could afford to spurn the art of the court eulogist … His placid existence as a pharmacist and a Sufi does not appear to have ever been interrupted by journeys. In his later years he lived a very retired life … He reached an age well over seventy … He died a violent death in the massacre which the Mongols inflicted on Nīšāpūr in April, 1221.6

As respectable as this account is in assembling stray bits of lore scattered through Attar’s writings and elsewhere, it fails to take into account the history of the city where he spent his life. The purpose of this essay is to fill in that history and to suggest how the urban environment of Nishapur may have affected Attar’s experience as a Sufi. A comparison with the life of another of Nishapur’s Sufis, Abu al-Qasim al-Qushairi, will reinforce the contention that Attar’s relation to his hometown had a powerful influence on his spiritual career.

Al-Qushairi had a greater impact on the history of Sufism than Attar did, but as a theoretician, not as a poet. His work, most notably his Risala (Epistle), which focused on how individuals seeking to pursue the Sufi path should comport themselves and relate to other travelers on the way, became a widely used summary of the many facets of behavior and mental attitudes that contributed to the Sufi life. In a more worldly sense, he was also influential because of his many personal links with important figures of his day. By contrast, no mention survives of any of Attar’s family, friends, or acquaintances.

The city of Nishapur, where both men lived their lives, suffered radical change between the days of al-Qushairi (986-1072) and those of Attar’s youth a century and a half later.7 In the year 1010, when al-Qushairi was a young man, Nishapur was at its peak. Its population almost certainly topped 150,000, making it the second largest city in the caliphate after Baghdad, the Abbasid capital. By the 1160s, however, Nishapur was a city in ruins. It’s central area with its grand mosques, schools, and markets had been abandoned, and the surviving population had found shelter in a walled suburb on the city’s outskirts. Al-Qushairi, in other words, pursued his career in a great and bustling metropolis, while Attar was surrounded by the ghost of that metropolis, its ruins providing a daily reminder of the fragility of human existence.

From the early days of the Arab conquest of Iran, the northeast province of Khurasan played an immensely creative role in defining Islam as a foundation for social relations. A host of scholars, writers, legists, and Sufis were native Khurasanis, and virtually all of them lived or sojourned for at least some period of time in Nishapur. They played innovative roles in creating institutions, notably, schools (madrasas) and Sufi convents (khangahs), that spread from Khurasan to the rest of the Islamic world. And Nishapur in eleventh century was the core locale from which the Shafi‘i law school and the Ash‘ari interpretation of theology disseminated, despite the fact that the eponyms of both schools had lived in Baghdad, al-Shafi‘i dying in 820 and al-Ash‘ari in 936.

Yet despite its economic vitality and cultural importance, Nishapur was seldom the capital of a dynastic state. It’s cotton goods and ceramics found buyers well outside its immediate vicinity, and the Silk Road caravans that brought luxury goods from China and Central Asia passed through it on their way to Baghdad. Its agriculture was based on irrigation by underground canals, which also supplied the city’s drinking water. Nishapur may then have been the largest city in the world not on a navigable waterway. Though the city’s dependency on land transport—thousands of pack animals a day bringing in foodstuffs and other necessary commodities—made it vulnerable to rural unrest or invasion, it was unwalled in its heyday and rarely subjected to military assault.

Abu al-Qasim al-Qushairi was born in Ustuva, a district north of Nishapur known as a place where some of the Arab tribal groups who brought Islam to Iran in the seventh century settled. Al-Qushairi was descended from such a group on both his father’s and his mother’s side, but he was not from a particularly distinguished or wealthy family. When he came to Nishapur as a young man, it was to seek his fortune, not to assume a position to which he was entitled by birth or family connections.

The two most eminent Sufis in Nishapur at that time were Abu Abd al-Rahman al-Sulami and Abu Ali al-Daqqaq. They are among the earliest Sufis known to have had lodgings and/or meeting houses, called duwaira or khangah, that continued to function after their deaths. Al-Daqqaq also had a madrasa, which was probably part of or synonymous with the same building. Al-Sulami collected lore about earlier Sufis and exemplars of piety, publishing their inspiring quotations and biographical tidbits in books about Sufism and a less known group called the Malamatiya. Another book, dealing with the virtues of young manhood (futuwwa), left a trace in al-Qushairi’s Risala, which lists futuwwa as contributing to the Sufi way.

Writings by Abu Ali al-Daqqaq have not survived, but his reputation for spiritual excellence has, along with that of his daughter Fatima, who seems to have been Nishapur’s paramount female Sufi. Fatima was born in 1001, the year her father’s madrasa was built, and was fourteen at the time of his death. Al-Qushairi succeeded Abu Ali as head of the madrasa, which was henceforth called the madrasa Qushairiya, and some years later married Fatima. The oldest of their several children was a son born in 1023.

Like his father-in-law and most other Sufis of that era, al-Qushairi became a devoted adherent of the Shafi‘i legal faction and made the pilgrimage to Mecca in the company of two of the foremost Shafi‘is, Abu Bakr Ahmad al-Baihaqi and Abu Muhammad al-Juwaini. Sixteen of al-Baihaqi’s works on the traditions of the Prophet, Shafi‘i law, and Ash‘ari theology have been published, and Imam al-Haramain al-Juwaini, the far-famed son of his pilgrimage companion, wrote of him: “There is no Shafi‘i except he owes a huge debt to al-Shafi‘i, except al-Bayhaqi, to whom al-Shafi‘i owes a huge debt for his works which imposed al-Shafi‘i’s school and his sayings.”8 Al-Baihaqi lived in a madrasa that was quite near to that of al-Qushairi.

As for Abu Muhammad al-Juwaini, whose Sufi brother spent so many years in Arabia that he was known as the Shaikh of Hijaz, his voluminous scholarship on Shafi‘i and Ash‘ari topics was exceeded only by his son, Imam al-Haramain. One of al-Qushairi’s sons reportedly said of the father: “In his time our … companions saw in him such perfection and high merit that they used to say: ‘If it were permissible to hold that Allah should send another prophet in our time, it would not have been other than he.’”9

A continued detailed exposition along these lines would reveal that Abu al-Qasim al-Qushairi knew everybody of importance in Nishapur. He was a central figure in an extensive network of scores of prominent figures from a dozen or so interrelated families that all shared a devotion to Shafi‘i law, Ash‘ari theology, and, in many instances, Sufi piety. Indeed, this social group, which eventually came to include the famous theologian al-Ghazali (d. 1111), a student of Imam al-Haramain al-Juwaini, powerfully influenced the subsequent intellectual, spiritual, and institutional development of Islam.

Nishapur’s centrality in the world of Islam was to change, however, by the middle of the twelfth century. Not only was it physically destroyed and largely depopulated, but its learned families died off or emigrated leaving a vacuum where once a score of madrasas had combined to make the city Islam’s leading center of education. The causes of the Nishapur’s collapse are several. In 1037 Tughril Beg, the leader of the Oghuz Turks from Central Asia, peacefully occupied the city after defeating the forces of the Ghaznavid ruler based in eastern Afghanistan. Thus began the Seljuq dynasty that would dominate and rearrange the political landscape between Afghanistan and the Mediterranean over the next two centuries.

Tughril’s vizier, Amid al-Mulk al-Kunduri, began his career as a protégé of Imam al-Muwaffaq al-Bastami, the leader of Nishapur’s Shafi‘i faction. Al-Kunduri seems to have retained his Shafi‘i affiliation until his mentor died in 1048, passing the leadership of the faction on to his son, Abu Sahl Muhammad al-Bastami. At nineteen, Abu Sahl Muhammad was a decade younger than al-Kunduri. It is reported that this succession did not go uncontested. Did al-Kunduri feel his mentor had given his son a position that should have passed to him? The historical record is silent as to the details, but that may have been why al-Kunduri conceived a great dislike for the new Shafi‘i chief. To be sure, the Seljuqs and their Oghuz followers are described as adhering to the Hanafi school of law, to which al-Kunduri now shifted his allegiance. But no historian believes that Tughril Beg was knowledgeable about the points of dispute between Hanafis and Shafi‘is. Otherwise it would be hard to understand how the Shafi‘i Nizam al-Mulk, al-Kunduri’s successor, who hailed from the city of Tus just east of Nishapur, could have served as the Seljuqs’ most powerful and influential vizier from 1063 to 1092.

Al-Kunduri’s animus against the Shafi‘i-Ash‘ari faction was so personal and so intense that he ordered the arrest of four persons: 1) Abu al-Qasim al-Qushairi, who was then around 65 years of age; 2) Abu al-Fadl Ahmad al-Furati, Nishapur’s ra’is (roughly “mayor”), a prosperous man from of provincial background who had taken wives from two leading families, one Shafi‘i and the other Hanafi; 3) Abu Ma‘ali Abd al-Malik al-Juwaini, the eminent son of al-Qushairi’s pilgrimage companion, who escaped into exile where he would earn the title Imam al-Haramain (Imam of the Two Holy Sanctuaries); 4) and the faction chief Abu Sahl Muhammad al-Bastami. Being about 25 and of a combative temperament, Abu Sahl Muhammad withdrew from town, raised a private army, and returned to fight a pitched battle in the main market to spring al-Qushairi and al-Furati from jail.

Though the Hanafi and Shafi‘i factions in Iran had been at odds for decades, this outbreak of fighting raised their competition to a new level. When Nizam al-Mulk succeeded al-Kunduri as vizier after Tughril Beg’s death in 1063, the persecution of the Shafi‘i-Ash‘ari faction was lifted, but the damage had been done. By the middle of the twelfth century, there was open factional warfare. In 1158, the Shafi‘is, led at that time by a great-grandnephew of Abu Sahl Muhammad brought in fighting men from other parts of Khurasan to make nightly forays against their Hanafi opponents, burning madrasas and the homes of factional leaders. A renewal of fighting in 1161 resulted in the destruction of 8 Hanafi and 17 Shafi‘i madrasas and the burning or dispersal of their libraries.

Adding to the immense damage done by this intraurban civil war, Nishapur suffered attacks by marauders. Some were bandits (ayyarun), but the most rapacious were Ghuzz tribesmen who had freed themselves from Seljuq control by defeating the sultan in battle in 1153. Famine immediately followed the first Ghuzz attack, and prices were still extraordinarily high four years later. A third attack occurred in the midst of the factional fighting in 1158-9.

On top of this came natural catastrophes, most devastatingly an earthquake. One source puts it in 1145 and another in 1160, remarking that in the aftermath the people of the city moved to the suburban quarter of Shadyakh. Since it is quite clear that the main city had not been abandoned for Shadyakh by 1145, the latter year is more likely to be correct. Even without the earthquake, however, Nishapur was suffering from a catastrophic shift in its winter weather pattern that had set in early in the eleventh century. For more than a hundred years there was an unusual frequency of extremely cold winters that contributed, along with nomadic depredations in the countryside, to crop failures, famines, and epidemics.

But what does this tale of woe have to do with Sufism? Possibly a great deal. Though we do not know the year of Attar’s birth, he is thought to have been born around 1145. If so, he would have been 16 in 1161, the year in which Nishapur’s surviving population abandoned the heart of their city and regrouped in Shadyakh. This was the result not of a conquest, but of the inability of the citizens of Islam’s second greatest city to control their factional feuding and concentrate on rebuilding in the aftermath of the destruction wrought by earthquake and marauders.

Attar, in other words, knew the greatness of Nishapur only through the vast post-apocalyptic landscape that occupied several square kilometers outside the eastern wall of Shadyakh. While it is probably true that he followed the trade of a druggist, as implied by the name Attar, there is specific mention that in 1158 Nishapur’s Street of the Druggists, where it is likely that Attar’s father had a shop, was deliberately burned down. When we think of Attar’s childhood, in other words, the image that should come to mind is not that of a lad growing up in a stable society and learning an honorable trade from his well-to-do father, but of the refugee children from Afghanistan and Syria who have shown us the human face of despair in recent decades.

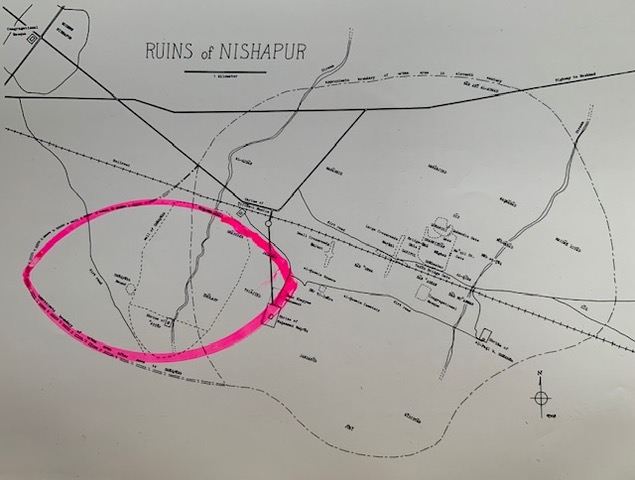

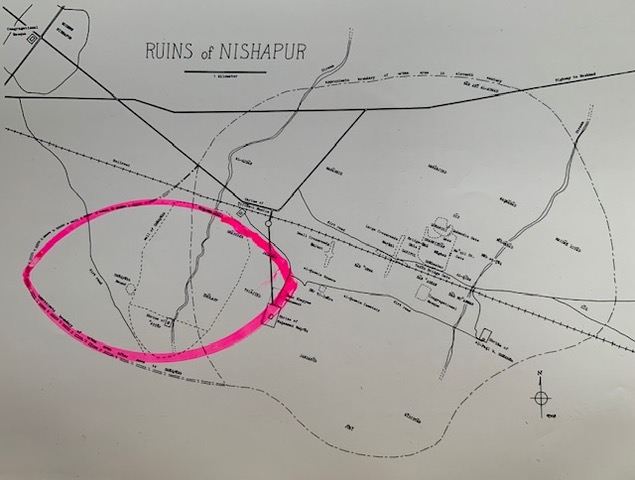

Figure 4. Approximate area of Old Nishapur that was still occupied during Attar’s lifetime. Image courtesy of the author.

We don’t know who Attar’s friends were, but we know who they weren’t. They were not learned scholars teaching hundreds of students in famous madrasas. The madrasas were gone. They were not bourgeois merchants pursuing their trades in conditions of peace and prosperity. Nishapur’s bazaars lay in ruins, their customers mostly migrated elsewhere. The city’s greatness had clearly passed by the time Attar was born. Members of some leading families had emigrated to Iraq, Syria, and Anatolia where they started new lives as scholars. Others had relocated to still functioning cities elsewhere in Iran. Our sources do not extend far enough into the twelfth century to tell us much about who remained in Shadyakh, but that in itself is evidence that the scholarly milieu that had fostered the preservation of a vast amount of information about Nishapur in the ninth through eleventh centuries was no longer thriving.

As Attar grew to adulthood and carried on to some degree the family trade, he would surely have wandered around the old city’s ruins, first probably in play, but later perhaps to visit the graves of famous scholars in the old city’s cemeteries. Later sources list some of their names and give instructions as to where to look for their tombstones. A somewhat pompous contemporary of Attar from the city of Hamadhan in western Iran wrote of post-apocalyptic Nishapur: “Where had been the assembly places of friendliness, the classes of knowledge, and the circles of patricians were now the grazing grounds of sheep and the lurking places of wild beasts and serpents.”10 Well and good, perhaps, for someone living a few hundred miles away; but for Attar, Nishapur, including its sad ruins, was home.

Now let us look comparatively at the Sufi outlook of al-Qushairi, a larger than life figure at the hub of Nishapur’s religious network during its heyday, and that of Attar, the forlorn refugee living his life in Shadyakh and hearing stories from old folks about what his hometown had been like before its devastation. An extensive comparison of their works is beyond the scope of this article and the competence of this writer, but a juxtaposition of their most famous works suggests that the milieu each of them was writing in affected their spirituality.

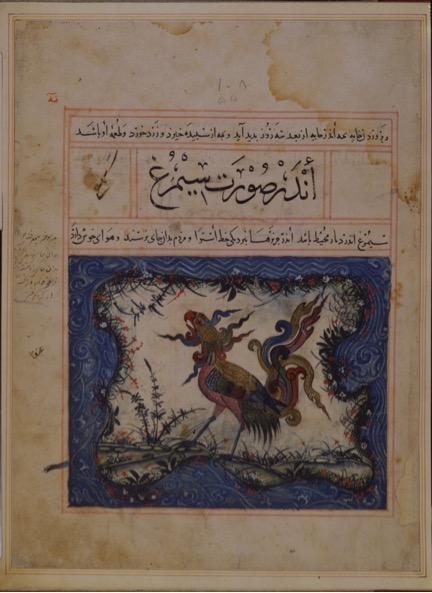

Attar’s Manteq al-Tayr tells the story of the birds of the world being prodded by the Hoopoe to undertake a perilous search for the divine Simurgh, a wonder-working bird from Iranian legend that was Attar’s symbol for God. When one bird after another complains that the way is too dangerous and that the life they are now living grants them everything they wish, the Hoopoe refutes them with anecdotes concerning a Princess, or a Miser, or a Handsome King, or whoever. He never names real persons or indicates which of his stories are his own inventions. Eventually the birds set off to traverse seven valleys, each more perilous than the one before. Most of the birds fall pitifully by the wayside. So when they finally arrive at the court of Simurgh, only thirty of them remain out of the millions that started. They then discover that the Simurgh—literally Thirty Birds in Persian—mirrors them, the thirty birds that have achieved enlightenment, and thus shows the divinity of spirit that lies within them.

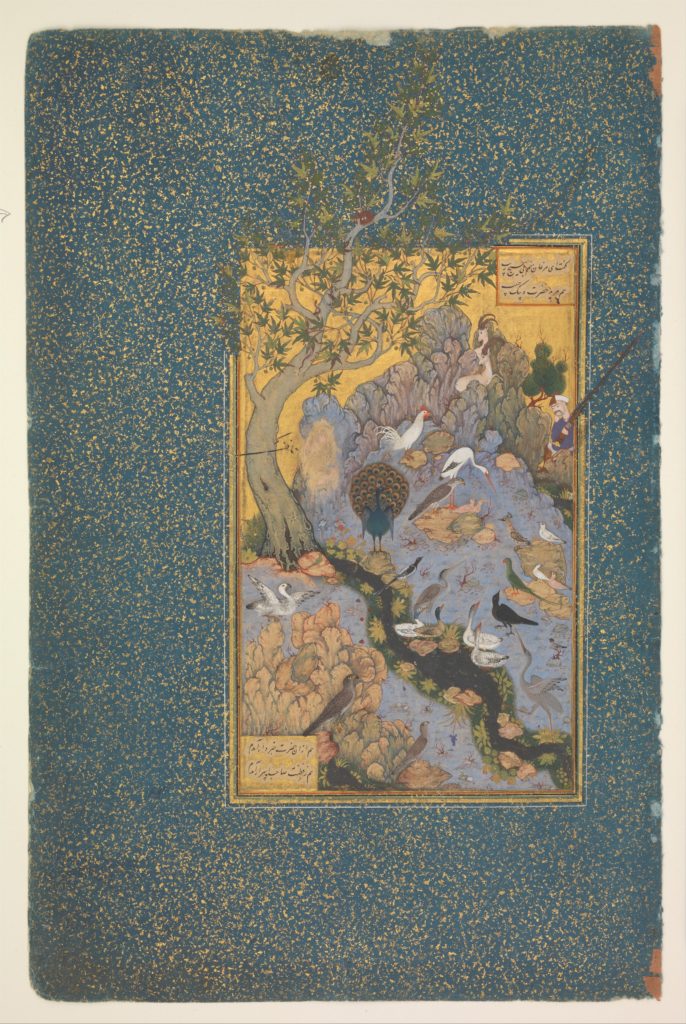

Figure 5. “The Concourse of the Birds”, Folio 11r from a Mantiq al-tair (Language of the Birds), ca. 1600. Painting by Habiballah of Sava. Image courtesty of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The contrast with al-Qushairi’s Risala could hardly be greater. Half of that text is devoted to the stations (maqamat) and states (ahwal) of those who pursue the Sufi path. Like Attar, al-Qushairi uses anecdotes and Sufi sayings to explicate each station or state, citing in each instance the name of the Sufi who told the anecdote or uttered the saying. Scores of sources and hundreds of anecdotes attest to his vast erudition, but the ones that inarguably reflect al-Qushairi’s personal association with the Sufis of Nishapur in its heyday are those he attributes to his father-in-law, Abu Ali al-Daqqaq, the directorship of whose madrasa–khangah he assumed upon Abu Ali’s death.

Al-Qushairi cites al-Daqqaq in 30 out of 43 chapters named for stations or states for a total of well over 50 anecdotes and quotations. What do these quotations reveal about the Sufi way of life when Nishapur was at its peak? And how do they contrast with the tale of the birds that Attar penned over a century later?

In describing Visionary Insight [firasa], Al-Qushairi relates: “At the beginning of my connection with the master Abu Ali al-Daqqaq, a class was convened for me in the mosque al-Mutarriz. Once I asked permission for some time to go to Nasa [a city to the north], and he allowed me to go. As I was walking with him on the way to his class one day, it occurred to me, ‘I wish he would teach my sessions in my place while I am gone.’ He turned to me and announced, ‘I will teach in your place in the sessions while you are gone.’ I walked on a little. Then it occurred to me that he was not in good health and it would trouble him to teach for me two days a week. I wished that he would reduce the sessions to only once per week. He turned to me and said, ‘If I am not able to teach two days a week for you, I will do it only one time per week.’ As I walked on a little, a third thing occurred to me. He turned to me and spoke the matter exactly.”11

Compare this commonplace exchange between a professor and his favorite graduate student with Attar’s stark vision: “As soon as you set your foot in the first valley, that of the Search, thousands of difficulties will assail you unceasingly at every stage. Every moment you will have to go through a hundred tests … You will have to perform arduous tasks to purify your nature. You will have to give up your riches and renounce all that you have.”12

In speaking of Steadfastness [istiqama], al-Qushairi writes: “My master Abu Ali al-Daqqaq said, ‘There are three degrees of steadfastness: setting things upright [taqwim], making things sound and straight [iqama], and being upright [istiqama]. Taqwim concerns discipline of the soul; iqama, refinement of the heart; and istiqama, bringing the inmost being near to God.’”13

Assigning subtly different meanings to three closely related Arabic words was characteristic of the pedantic style of classroom instruction in Nishapur’s Sufi gatherings. Attar, on the other hand, writes in Persian and displays no interest in academic linguistic games.

In his chapter on Trust in God [tawakkul], al-Qushairi writes: “My master Abu Ali al-Daqqaq said, ‘Trusting in God is the quality of the believers, surrender is the quality of the saints, and assigning one’s affairs to God is the quality of those who assert His unity.’ So trust in God is the quality of the common people, surrender is the quality of the elite, and assigning one’s affairs to God is the quality of the elite of the elite.”14

Later, when writing on Satisfaction [rida], al-Qushairi says: “The Iraqis and the Khurasanis differ concerning satisfaction. Is it a state or a station? The people of Khurasan assert, ‘Satisfaction is one of the stations. It is the culmination of trusting God. This means that it is attributable to what the servant attains by his own effort.’ The Iraqis state, ‘Satisfaction is one of the states, not something attained by the servant. Rather it is something that alights in the heart, as with the other states.’ A synthesis of the two views is possible. It would be stated thus, ‘The beginning of satisfaction is attained by the servant and is a station, although in the end it is a state and not something to be attained.’15

The odor of the academic classroom pervades both of these stories. In the first, the professor makes subtle distinctions between the qualities of different social strata. By contrast, Attar does not distinguish between the lowliest birds and the greatest. In the second, the professor contrasts and explains two ideas and then offers a clever solution that shows how both might be deemed correct.

How different the atmosphere of Attar where a bird says, “I apprehend that I shall die of fear during the very first stage of the journey,” and the Hoopoe replies, “We are foredoomed to death … Therefore renounce the world and prepare for the journey to the realm of non-existence. Do not spoil the chances of Eternal Life for the sake of this mean world.”16

When al-Qushairi takes up the subject of Remembrance [dhikr], he touches on the central ritual of most Sufi groups, collective recitations affirming constant remembrance of God, sometimes consisting simply of chanting the word Allah [God] or Hu [He, namely, God]. “The sheikh Abu Abd al-Rahman [al-Sulami, al-Daqqaq’s most famous Sufi contemporary] asked the master Abu Ali al-Daqqaq, ‘Is remembrance or meditation better?’ He retorted, ‘What do you say?’ He answered, ‘In my opinion remembrance is better than meditation because God described Himself as making remembrance but not as meditating. Whatever is a characteristic of God is better than something that is peculiar to men.’ The master Abu Ali approved of this view.”17

Attar’s birds do neither. They are not organized in Sufi congregations, and their journey full of peril and distraction provides little opportunity for either ritual remembrance or individual meditation.

Finally, on the subject of Correct Behavior [adab], al-Qushairi informs us that: “The master Abu Ali al-Daqqaq said, ‘The servant reaches Paradise by obeying God, He reaches God by observing correct behavior in obeying Him.’ He also said, ‘I saw someone who was about to move his hand during prayer to pick his nose but his hand was stopped.’ He refers, obviously, to himself here because it is impossible for one man to know that the hand of another man was stopped.” Further on he tells us that al-Daqqaq said: “Abandoning correct behavior results in expulsion. One who is ill-mannered in the courtyard will be sent back to the gate. One who is ill-mannered at the gate will be sent to watch over the animals.”18

There is no room for “correct behavior” in Attar’s tale of the birds, much less stories about nose-picking and bad manners in the courtyard. The birds must traverse seven valleys in their search for the Simurgh, and most of them will die. Only thirty reach their destination. The lads seeking to advance along the Sufi path in the classrooms of Abu al-Qasim al-Qushairi and Abu Ali al-Daqqaq had to study hard and observe proper decorum, but none of them expected to perish along the way. They surely would have enjoyed reading Attar’s parable, as Sufis of later centuries invariably did, but they would no more have seen it as describing the spiritual path they themselves were embarked upon than a graduate student in an American university today would see his own likeness in Herman Hesse’s Steppenwolf or Jack Kerouac’s On the Road.

Attar himself, on the other hand, may well have looked at the devastation that surrounded him—the disappearance of his city’s academic milieu; the grief that must have afflicted every family in the wake of nomad and bandit attacks, earthquake, and civil war; the emigration of the city’s spiritual elite—and seen something much closer to the plight and near hopelessness of the birds. For him, succeeding in the Sufi quest was a matter of life or (far more likely) death rather than maintaining decorum in a classroom and parsing the nuances of Arabic grammar.

Notes

- B. Reinert, “AṬṬĀR, FARĪD-AL-DĪN,” Encyclopaedia Iranica, III/1, pp. 20-25, available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/2330-4804_EIRO_COM_6077. First published online: 2020. ↑

- The year 1145 has also been suggested for this earthquake, but the political turmoil of 1161 detailed below makes 1160 more probable. ↑

- Muhammad ar-Rawandi, Rahat as-sudur wa ayat as-surur: Being a History of the Seljuqs. Edited by M. Iqbal. E.J.W. Gibb Memorial Series, n.s. II, London, Luzac, 1912, p. 182. ↑

- I argue in my book Cotton, Climate, and Camels: A Moment in World History (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011) that a distinct chilling of the climate contributed to all of Nishapur’s woes. Agricultural production failed to recover, and the cotton industry, which had been the mainstay of the urban economy, collapsed. ↑

- Hans-Peter Schmidt, “SIMORḠ,” Encyclopaedia Iranica, available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/2330-4804_EIRO_COM_188 (accessed January 2022). ↑

- B. Reinert, “AṬṬĀR, FARĪD-AL-DĪN,” Encyclopaedia Iranica, III/1, pp. 20-25, available online at http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/attar-farid-al-din-poet (accessed March 2017). ↑

- Information about Nishapur and the important figures who lived there comes from several of my publications, most importantly, The Patricians of Nishapur: A Study in Medieval Islamic Social History, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1972; “The Political-Religious History of Nishapur in the Eleventh Century,” in D.S. Richards, ed., Islamic Civilization 950-1150, Oxford: Bruno Cassirer, pp. 71-91; Islam: The View from the Edge, New York: Columbia University Press, 1993; and Cotton, Climate, and Camels in Early Islamic Iran: A Moment in World History, New York: Columbia University Press, 2009. ↑

- Jibril Haddad, “Imam al-Bayhaqi 384-458,” http://www.sunnah.org/history/Scholars/imam_bayhaqi.htm (recovered March, 2017). ↑

- G. F. Haddad, “Abu Muhammad al-Juwayni,” http://www.sunnah.org/history/Scholars/al_juwayni_al_kabir.htm(recovered March, 2017). ↑

- Muhammad al-Rawandi, Rahat al-sudur wa ayat al-surur: Being a History of the Seljuqs, ed. M. Iqbal, E.J.W. Gibb Mmorial Seris, n.d. II, London: Luzac, 1921, p. 182. ↑

- Al-Qushayri, Principles of Sufism, tr. B.R. von Schlegell, Oneonta, New York: Mizan Press, 1990, ch. 32. ↑

- Farid al-Din Attar, Conference of the Birds: A Seeker’s Journey to God, tr. R. P. Masani, Boston: Weiser Books, 2001, p. 33. ↑

- Al-Qushayri, ch. 25. ↑

- Al-Qushayri, ch. 17. ↑

- Al-Qushayri, ch. 22. ↑

- Attar, p. 23. ↑

- Al-Qushayri, ch. 30. ↑

- Al-Qushayri, ch. 40. ↑

Farid al-Din Attar, the Man

Two Views

Part I. The Druggist of Nishapur

Farid al-Din Attar, a druggist living in the city of Nishapur, wrote a parable that has captivated readers and inspired artists for almost a thousand years. The Mantiq al-Tayr (Conference of the Birds) imagines a multitude of birds setting out on a quest to find the Simorgh, a divine raptorial bird in Iranian mythology. The birds traverse seven spiritual valleys: Quest, Love, Understanding, Independence and Detachment, Unity, Astonishment and Bewilderment, and Deprivation and Death. Only thirty birds survive the perils of the journey and achieve a vision of the Simorgh. But that vision turns out to be their own selves reflected in a heavenly mirror, for the name of the divine Simorgh also means “thirty birds” in Persian (si = thirty + morgh = bird).

In his sketch of Attar’s live in the Encyclopedia Iranica, B. Reinert tells us the following:

While ʿAṭṭār’s works say little else about his life, they tell us that he practiced the profession of pharmacy and personally attended to a very large number of customers . . . His placid existence as a pharmacist and a Sufi does not appear to have ever been interrupted by journeys. In his later years he lived a very retired life … He reached an age well over seventy … He died a violent death in the massacre which the Mongols inflicted on Nīšāpūr in April, 1221.1

A second work by Attar, Tadhkirat-i Awliya’, preserves capsule biographies of 72 earlier Sufis, many of them taken from Sufi works composed a century or more earlier by other Nishapur mystics. Though this attests to Attar’s depth of Sufi erudition, none of the mystics in the collection are named in Mantiq al-Tayr. Nor do the seven valleys correlate either with what the Sufis had written about stages a Sufi aspirant should pass through in order to become enlightened, or with the conception of a cosmic hierarchy of Sufi authority current in Attar’s era. According to this schema, a single Qutb occupied the highest place in the hierarchy, followed by three Nuqaba, then four Awtad, seven Abrar, 40 Abdal, and 300 Akhyar.

How, then, did the vision of the birds’ mystic journey arise, if not from a more general Sufi tradition? Being personally lacking in both spiritual insight and a deep knowledge of Sufi literature, the conclusions I shall put forward in this essay are based primarily upon my understanding of what the city of Nishapur was like during Attar’s lifetime.

My starting point is an assumption that Attar could not have envisioned the birds’ progression through the seven valleys if he had not, in some sense, already traversed them himself and experienced the theophany they finally attain to. If that is the case, however, how does a deep spiritual realization of Deprivation and Death square with his supposed “placid existence as a pharmacist and a Sufi”?

A map of Nishapur tells a sad tale. I drew in the 1960s after weeks of wandering through the field of buried ruins that is all that is left of the medieval city, and subsequently examining aerial photographs taken in the 1950s.

The circular area with the crossroads at the upper left demarcates the modern city’s built-up urban area at the time the photographs were taken. The population at that time was approximately 30,000. The stream that runs from north to south 2.5 kilometers east of the modern city bisects a walled area (dotted line) that, with its semicircular southern extension, is about twice the size of the 1950s city. The tomb of Attar, a lovely domed structure now surrounded by an extensive garden, is marked on the map at the center of the southern wall, above the semicircular extension. This location jibes with the tradition that Attar was killed at a ripe old age during the Mongol devastation of the city in 1221. The walls similarly support a tradition that the target of the Mongol attack was a region of the city named Shadyakh.

As for the larger city of which Shadyakh was a part, its extent is indicated by lighter of the two dashed lines that cuts through and vastly surpasses the Mongol era walls. Much of that area was doubtless taken up with gardens and orchards supplying the city’s markets; but my guess, based on the area within that line, is that Shadyakh was smaller than the large city by a factor of at least five. Thus if Shadyakh, being roughly the size of the modern city of the 1950s, had a population of similar size in Attar’s day, then the population of the larger metropolis, at its peak a century or so before Attar’s birth, should have been on the order of 200,000.

No wall encompassed the larger city. Hence, the perimeter I drew on the map derives from two sources: the aerial photographs of the ruins and ground observations that I made in 1966. Irrigation practices in the region draw water from aquifers that are tapped in the mountains north of the city and led to the city through underground channels called qanats. The gentle slope of these channels, as calculated by expert tunneling engineers, brings the water to the surface in the form of small streams, but qanats flowing beneath built-up areas could also be accessed through staircases. Temporary dams divert the steady flow of water that finally exits the qanat onto fields on either side. Low, closely spaced dikes follow the slope of the land so that the water irrigates the highest part of the field; and then, after a fixed amount of time, the dikes are opened so it irrigates the next highest diked area. And so it goes until all of the farmland is irrigated.

The lines of dikes show up on aerial photographs function exactly like contour lines on a map. In the completely flat landscape around Nishapur, they are normally parallel to one another and perpendicular to the direction of water flow. When the land surface is irregular, however, the hills and depressions that betray the presence of destroyed buildings fifteen feet or so underground cause the perpendicular lines to curve, and even form circles. The perimeter I have drawn on the map demarcates the limit of such hummocky land.

Figure 2. Aerial photograph of Nishapur ruins circa 1955. Note curved contour lines signaling hills and depressions.

My site observations that supplement this indicator of the extent of the ruins derive from the abundant traces of urban remains brought to the surface by yearly plowing, despite the many feet of wind-borne dust that have accumulated over the millennium since the population that dwelt in Nishapur during its heyday disappeared. I would pick a compass direction from a central point in the ruins and then count the number of paces from that point to the point where the myriad potsherds, glass shards, and brickbats no longer appeared underfoot.

I go into all this detail to assure the reader that the difference in area between the walled Shadyakh in which Attar lived his adult life and the enormous city that preceded it is not mere conjecture. Rather, it confirms the historical fact that Attar serviced his pharmacy customers clustered in a walled community surrounded by the deserted buildings of what had been, just a generation before, the largest and most important cultural center in Iran, if not in the entire Islamic world.

As an adult, Attar looked, on almost a daily basis, at streets bordered by crumbling houses, mosques with collapsed domes, and charred markets still littered with occupational bric-a-brac. Today’s news photos from war ravaged Syria and Afghanistan, or those from Beirut during its civil war in the 1980s, provide a good model for imagining the abandoned cityscape that lay outside the walls of Shadyakh.

But what about Attar in his childhood and teenaged years? Reports that he was in his seventies when the Mongols killed him have led scholars to suggest that he was born around 1145. If that is so, he was fifteen when a devastating earthquake rumbled through.2 And the following year saw the final abandonment of the main city. Yet natural catastrophe simply put the capstone on many years of strife and destruction.

The great city’s educated elite was riven by factional discord that intensified over the course of the eleventh century. The two factions were labeled Hanafi and Shafi‘i for the two preeminent schools of Islamic legal interpretation, but these names surely conceal social, economic, and political cleavages that are no longer recoverable. To skirt around these unknowable aspects of Nishapur’s civil war and focus on its destructive side, I will call the two factions the Pinks and the Greys.

In 1153, when Attar may have been eight years old, a group of Turkic nomads refused to obey the reigning Sultan’s demand for a tribute of 30,000 sheep. The Sultan responded militarily, but surprisingly, the nomads defeated his army and took him captive, leaving northeastern Iran undefended. The nomads proceeded to sack a number of cities. Two of Nishapur’s largest mosques were destroyed, and 15,000 male corpses were reportedly recovered from two city quarters. Women and children were carried off as slaves, and the nomads spent several days searching for loot. The walled Inner City, with a citadel on its northern edge (right hand side of Fig. 2), fended off the raiders. But they returned after sacking some smaller cities in the vicinity, and this time they overran and pillaged the Inner City as well. On the heels of this second attack, bandit gangs moved into the city to loot whatever the nomads had missed.

An officer of the Sultan named Ay Abah then asserted control over the city and continued as its overlord for twenty years, defending it from both nomads and rival commanders. But a famine that set in immediately after the nomad withdrawal stunted any quick recovery. A city the size of Nishapur depended on the regular arrival of thousands of camel loads of food and other necessities produced in outlying villages, but those villages had also suffered from the nomad rampage. In 1157 a report of skyrocketing prices indicates that rural food production was still lagging behind the city’s requirements.

Meanwhile, the rivalry between the Pinks and the Greys continued apace. In 1158, some Pinks killed a Grey, and the Grey leader demanded that the killers be turned over to him. The Pink leader refused. The Greys attacked, killed some Pinks, destroyed the Pink leader’s home, and burned out several streets, including the druggists’ market. Inasmuch as tradesmen in medieval Muslim cities normally clustered together to manufacture and sell their products, it is quite likely that Attar’s father lost his livelihood at this time. The fighting spread over the following months. Pink reinforcements came in from neighboring cities, and every night gangs of Pinks and Greys set fires in the quarters of their foes. Then the nomads attacked for a third time.

Attar probably witnessed all of this and experienced the loss of his father’s shop as a young teenager. But he would have been too young to take part in the fighting between the Pinks and the Greys that accelerated after a leading Grey was killed. The Pinks lost schools, mosques, and markets, and their leader fled the city. Within months, however, he returned in the company of the overlord Ay Abah. The revived Pinks took destructive revenge on the Greys, who seem to have retreated to the citadel. Ay Abah worked out a truce, but in 1161 the fighting resumed. A major Pink mosque was destroyed, along with its library, as were thirteen Pink and eight Grey schools that had survived the earlier rounds of pillaging. Precious collections of books were burned or sold off cheaply.

It was at this point that Ay Abah selected Shadyakh as the site for a new city. It was a spacious area on the western edge of the great metropolis that had benefited from two episodes of princely building projects in the ninth and eleventh centuries. Ay Abah, who had sponsored the Pink leader’s return to the city, saw to the rebuilding Shadyakh’s walls and moved there with his supporters, leaving the ruins to the Greys, who clustered in the Inner City and awaited Ay Abah’s attack. Holding Nishapur’s only high ground, the Greys mounted mangonels on the walls and cast stones onto any Pink targets they espied.

Ay Abah’s attack came in the middle of the year. During his two-month siege a stone from a mangonel killed the Pink leader. The citadel held out, only to surrender a few months later in 1162. The historian who recorded many of the details I have cited completed his chronicle some 40 years later, when eye-witnesses of Nishapur’s fall were still alive. He says of the abandoned metropolis:

“Where had been the assembly places of friendliness, the classes of knowledge, and the circles of scholars were now the grazing grounds of sheep and the lurking places of wild beasts and serpents.”3

If Attar was born in 1145, he had still not passed his twentieth birthday. Had he experienced the valley of Deprivation and Death? Most probably, along with everyone in his generation. But the Mantiq al-Tayr sees this valley as the ultimate stage of contacting the divine, not as a despairing depth of the sort that many refugees from war and devastation experience. So some sort of transformation takes place in Attar’s mind after 1162. He somehow re-experiences Deprivation and Death as the culminating stage of a sequence of feelings symbolized by the first six valleys.

Today’s widely recognized stages of grief — denial, numbness, and shock; bargaining; depression; anger; and acceptance — offer a suggestive comparison. The grief-stricken individual only perceives these stages in retrospect. Similarly, I would suggest, Attar’s transit through the seven valleys signals a deep, lengthy, and surprisingly positive period of meditation upon his unending experience of Nishapur’s destruction, analogous, I would suggest, to Sigmund Freud’s deep dive into the dreams of his childhood.

I estimate that 80 percent of the population permanently moved away, the ablest (or richest) of them resettling in the Arab lands and Anatolia to the west, or Afghanistan and India to the east. Though Nishapur’s ruins could have sheltered remnants of the population, without a robust and productive rural economy, rebuilding on a grand scale was impossible.4 Soon lists were being compiled to help pious pilgrims as they toured the ruins looking for the graves of famous saints and scholars. There were apparently no local residents left to help them. Unlike today’s survivors of urban destruction, however, who can realistically hope to see international reconstruction aid flowing to their city, there was no light at the end of Nishapur’s tunnel of horror. Shadyakh was destroyed, and Attar killed, in the Mongol invasion of 1221.

One must assume that Attar’s meditation on Nishapur’s fall was informed by an increasing understanding of Sufism. Yet Mantiq al-Tayr need not be read solely was a Sufi work. The word Sufi does not appear, nor does the name of any known Sufi. And most strikingly, for a branch of spirituality that was marked by individual verbal explosions expressing an ultimate experience of the divine — Ana al-Haqq (“I am the Truth”), or Ma fi hadhihi al-jubba illa Allah (“There is nothing in this shirt but God”) — it is a group rather than an individual that achieves contact with the divine in the seventh valley.

I know of no evidence that the Simorgh, a mythical raptorial bird, was ever understood to be a composite of “thirty birds” before Attar took it as his metaphor for the divine. Thirty, unlike seven or forty, was not a weighty symbolic number in the lands of Islam.5 To be sure, si meant thirty in Persian and Kurdish, but the syllable is not normally interpreted this way when it appears as a prefix in other Persian words. And I take it for granted that Attar never anticipated the crowded ornithological extravaganzas that Iranian miniaturists had begun to paint by the fifteenth century.

Figure 3. “The Simorḡ,” Marāḡa, 697 or 699/ca. 1297-1300, illustration from the Manāfeʿ-e ḥayawān. Courtesy of The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York, Ms. M. 500, fol. 55r.

So how did Attar hit upon this metaphor? I think again of Freud resorting to the myths of Oedipus and Electra to make his understanding of the unconscious palatable to an educated audience. I believe he was actually recreating the process that Attar went through. 1) Examine to the greatest depth one’s inner feelings. 2) Recognize that those feelings are not simply personal, but common to other people once they have carried out a similar self-examination. 3) Search the common store of myth and legend for tales that can symbolize the link between the mental condition of an individual and the mentality of humankind at large. 4) Set the metaphor free to be exploited and utilized by generations yet unborn.

If I put aside the purely Sufi interpretation of Attar’s parable, I can easily imagine that his thirty birds were actually human survivors of the fall of Nishapur. Perhaps Attar found exultation in his tracing of a spiritual path that could look upon Deprivation and Death and see not despair, but a point of contact with the divine, and he wanted to open his path to people he knew in Shadyakh as a way to helping them come to grips with the vanishing of their great metropolis. Thousands of birds begin the journey, but most of them fall away. Were those that persevered to the end, the thirty, actually fellow citizens of Attar who saw themselves, collectively, in the divine mirror as being at the culmination of their spiritual quest?

When in his career the druggist of Nishapur wrote Mantiq al-Tayr is unknown. Is it not possible, therefore, that he had not yet become a Sufi when he was struck by the magic of the Simorgh?

Part II. Nishapur

Farid al-Din Attar (1145?-1221) is both the best known and the least known Sufi from the city of Nishapur. He is the best known because Manteq al-Tayr (Conference of the Birds), a parable about the human quest for God, is one of the world’s most widely read and admired expressions of the Sufi vision and way. But he is the least known because so little information has been preserved regarding the details of his life. Writing in the Encyclopedia Iranica, B. Reinert tells us the following:

While ʿAṭṭār’s works say little else about his life, they tell us that he practiced the profession of pharmacy and personally attended to a very large number of customers … He evidently started writing certain books … while at work in the pharmacy … Anyway he was fortunate in not depending on his muse for his livelihood. He could afford to spurn the art of the court eulogist … His placid existence as a pharmacist and a Sufi does not appear to have ever been interrupted by journeys. In his later years he lived a very retired life … He reached an age well over seventy … He died a violent death in the massacre which the Mongols inflicted on Nīšāpūr in April, 1221.6

As respectable as this account is in assembling stray bits of lore scattered through Attar’s writings and elsewhere, it fails to take into account the history of the city where he spent his life. The purpose of this essay is to fill in that history and to suggest how the urban environment of Nishapur may have affected Attar’s experience as a Sufi. A comparison with the life of another of Nishapur’s Sufis, Abu al-Qasim al-Qushairi, will reinforce the contention that Attar’s relation to his hometown had a powerful influence on his spiritual career.

Al-Qushairi had a greater impact on the history of Sufism than Attar did, but as a theoretician, not as a poet. His work, most notably his Risala (Epistle), which focused on how individuals seeking to pursue the Sufi path should comport themselves and relate to other travelers on the way, became a widely used summary of the many facets of behavior and mental attitudes that contributed to the Sufi life. In a more worldly sense, he was also influential because of his many personal links with important figures of his day. By contrast, no mention survives of any of Attar’s family, friends, or acquaintances.

The city of Nishapur, where both men lived their lives, suffered radical change between the days of al-Qushairi (986-1072) and those of Attar’s youth a century and a half later.7 In the year 1010, when al-Qushairi was a young man, Nishapur was at its peak. Its population almost certainly topped 150,000, making it the second largest city in the caliphate after Baghdad, the Abbasid capital. By the 1160s, however, Nishapur was a city in ruins. It’s central area with its grand mosques, schools, and markets had been abandoned, and the surviving population had found shelter in a walled suburb on the city’s outskirts. Al-Qushairi, in other words, pursued his career in a great and bustling metropolis, while Attar was surrounded by the ghost of that metropolis, its ruins providing a daily reminder of the fragility of human existence.

From the early days of the Arab conquest of Iran, the northeast province of Khurasan played an immensely creative role in defining Islam as a foundation for social relations. A host of scholars, writers, legists, and Sufis were native Khurasanis, and virtually all of them lived or sojourned for at least some period of time in Nishapur. They played innovative roles in creating institutions, notably, schools (madrasas) and Sufi convents (khangahs), that spread from Khurasan to the rest of the Islamic world. And Nishapur in eleventh century was the core locale from which the Shafi‘i law school and the Ash‘ari interpretation of theology disseminated, despite the fact that the eponyms of both schools had lived in Baghdad, al-Shafi‘i dying in 820 and al-Ash‘ari in 936.

Yet despite its economic vitality and cultural importance, Nishapur was seldom the capital of a dynastic state. It’s cotton goods and ceramics found buyers well outside its immediate vicinity, and the Silk Road caravans that brought luxury goods from China and Central Asia passed through it on their way to Baghdad. Its agriculture was based on irrigation by underground canals, which also supplied the city’s drinking water. Nishapur may then have been the largest city in the world not on a navigable waterway. Though the city’s dependency on land transport—thousands of pack animals a day bringing in foodstuffs and other necessary commodities—made it vulnerable to rural unrest or invasion, it was unwalled in its heyday and rarely subjected to military assault.

Abu al-Qasim al-Qushairi was born in Ustuva, a district north of Nishapur known as a place where some of the Arab tribal groups who brought Islam to Iran in the seventh century settled. Al-Qushairi was descended from such a group on both his father’s and his mother’s side, but he was not from a particularly distinguished or wealthy family. When he came to Nishapur as a young man, it was to seek his fortune, not to assume a position to which he was entitled by birth or family connections.

The two most eminent Sufis in Nishapur at that time were Abu Abd al-Rahman al-Sulami and Abu Ali al-Daqqaq. They are among the earliest Sufis known to have had lodgings and/or meeting houses, called duwaira or khangah, that continued to function after their deaths. Al-Daqqaq also had a madrasa, which was probably part of or synonymous with the same building. Al-Sulami collected lore about earlier Sufis and exemplars of piety, publishing their inspiring quotations and biographical tidbits in books about Sufism and a less known group called the Malamatiya. Another book, dealing with the virtues of young manhood (futuwwa), left a trace in al-Qushairi’s Risala, which lists futuwwa as contributing to the Sufi way.

Writings by Abu Ali al-Daqqaq have not survived, but his reputation for spiritual excellence has, along with that of his daughter Fatima, who seems to have been Nishapur’s paramount female Sufi. Fatima was born in 1001, the year her father’s madrasa was built, and was fourteen at the time of his death. Al-Qushairi succeeded Abu Ali as head of the madrasa, which was henceforth called the madrasa Qushairiya, and some years later married Fatima. The oldest of their several children was a son born in 1023.

Like his father-in-law and most other Sufis of that era, al-Qushairi became a devoted adherent of the Shafi‘i legal faction and made the pilgrimage to Mecca in the company of two of the foremost Shafi‘is, Abu Bakr Ahmad al-Baihaqi and Abu Muhammad al-Juwaini. Sixteen of al-Baihaqi’s works on the traditions of the Prophet, Shafi‘i law, and Ash‘ari theology have been published, and Imam al-Haramain al-Juwaini, the far-famed son of his pilgrimage companion, wrote of him: “There is no Shafi‘i except he owes a huge debt to al-Shafi‘i, except al-Bayhaqi, to whom al-Shafi‘i owes a huge debt for his works which imposed al-Shafi‘i’s school and his sayings.”8 Al-Baihaqi lived in a madrasa that was quite near to that of al-Qushairi.

As for Abu Muhammad al-Juwaini, whose Sufi brother spent so many years in Arabia that he was known as the Shaikh of Hijaz, his voluminous scholarship on Shafi‘i and Ash‘ari topics was exceeded only by his son, Imam al-Haramain. One of al-Qushairi’s sons reportedly said of the father: “In his time our … companions saw in him such perfection and high merit that they used to say: ‘If it were permissible to hold that Allah should send another prophet in our time, it would not have been other than he.’”9

A continued detailed exposition along these lines would reveal that Abu al-Qasim al-Qushairi knew everybody of importance in Nishapur. He was a central figure in an extensive network of scores of prominent figures from a dozen or so interrelated families that all shared a devotion to Shafi‘i law, Ash‘ari theology, and, in many instances, Sufi piety. Indeed, this social group, which eventually came to include the famous theologian al-Ghazali (d. 1111), a student of Imam al-Haramain al-Juwaini, powerfully influenced the subsequent intellectual, spiritual, and institutional development of Islam.

Nishapur’s centrality in the world of Islam was to change, however, by the middle of the twelfth century. Not only was it physically destroyed and largely depopulated, but its learned families died off or emigrated leaving a vacuum where once a score of madrasas had combined to make the city Islam’s leading center of education. The causes of the Nishapur’s collapse are several. In 1037 Tughril Beg, the leader of the Oghuz Turks from Central Asia, peacefully occupied the city after defeating the forces of the Ghaznavid ruler based in eastern Afghanistan. Thus began the Seljuq dynasty that would dominate and rearrange the political landscape between Afghanistan and the Mediterranean over the next two centuries.

Tughril’s vizier, Amid al-Mulk al-Kunduri, began his career as a protégé of Imam al-Muwaffaq al-Bastami, the leader of Nishapur’s Shafi‘i faction. Al-Kunduri seems to have retained his Shafi‘i affiliation until his mentor died in 1048, passing the leadership of the faction on to his son, Abu Sahl Muhammad al-Bastami. At nineteen, Abu Sahl Muhammad was a decade younger than al-Kunduri. It is reported that this succession did not go uncontested. Did al-Kunduri feel his mentor had given his son a position that should have passed to him? The historical record is silent as to the details, but that may have been why al-Kunduri conceived a great dislike for the new Shafi‘i chief. To be sure, the Seljuqs and their Oghuz followers are described as adhering to the Hanafi school of law, to which al-Kunduri now shifted his allegiance. But no historian believes that Tughril Beg was knowledgeable about the points of dispute between Hanafis and Shafi‘is. Otherwise it would be hard to understand how the Shafi‘i Nizam al-Mulk, al-Kunduri’s successor, who hailed from the city of Tus just east of Nishapur, could have served as the Seljuqs’ most powerful and influential vizier from 1063 to 1092.

Al-Kunduri’s animus against the Shafi‘i-Ash‘ari faction was so personal and so intense that he ordered the arrest of four persons: 1) Abu al-Qasim al-Qushairi, who was then around 65 years of age; 2) Abu al-Fadl Ahmad al-Furati, Nishapur’s ra’is (roughly “mayor”), a prosperous man from of provincial background who had taken wives from two leading families, one Shafi‘i and the other Hanafi; 3) Abu Ma‘ali Abd al-Malik al-Juwaini, the eminent son of al-Qushairi’s pilgrimage companion, who escaped into exile where he would earn the title Imam al-Haramain (Imam of the Two Holy Sanctuaries); 4) and the faction chief Abu Sahl Muhammad al-Bastami. Being about 25 and of a combative temperament, Abu Sahl Muhammad withdrew from town, raised a private army, and returned to fight a pitched battle in the main market to spring al-Qushairi and al-Furati from jail.

Though the Hanafi and Shafi‘i factions in Iran had been at odds for decades, this outbreak of fighting raised their competition to a new level. When Nizam al-Mulk succeeded al-Kunduri as vizier after Tughril Beg’s death in 1063, the persecution of the Shafi‘i-Ash‘ari faction was lifted, but the damage had been done. By the middle of the twelfth century, there was open factional warfare. In 1158, the Shafi‘is, led at that time by a great-grandnephew of Abu Sahl Muhammad brought in fighting men from other parts of Khurasan to make nightly forays against their Hanafi opponents, burning madrasas and the homes of factional leaders. A renewal of fighting in 1161 resulted in the destruction of 8 Hanafi and 17 Shafi‘i madrasas and the burning or dispersal of their libraries.

Adding to the immense damage done by this intraurban civil war, Nishapur suffered attacks by marauders. Some were bandits (ayyarun), but the most rapacious were Ghuzz tribesmen who had freed themselves from Seljuq control by defeating the sultan in battle in 1153. Famine immediately followed the first Ghuzz attack, and prices were still extraordinarily high four years later. A third attack occurred in the midst of the factional fighting in 1158-9.

On top of this came natural catastrophes, most devastatingly an earthquake. One source puts it in 1145 and another in 1160, remarking that in the aftermath the people of the city moved to the suburban quarter of Shadyakh. Since it is quite clear that the main city had not been abandoned for Shadyakh by 1145, the latter year is more likely to be correct. Even without the earthquake, however, Nishapur was suffering from a catastrophic shift in its winter weather pattern that had set in early in the eleventh century. For more than a hundred years there was an unusual frequency of extremely cold winters that contributed, along with nomadic depredations in the countryside, to crop failures, famines, and epidemics.

But what does this tale of woe have to do with Sufism? Possibly a great deal. Though we do not know the year of Attar’s birth, he is thought to have been born around 1145. If so, he would have been 16 in 1161, the year in which Nishapur’s surviving population abandoned the heart of their city and regrouped in Shadyakh. This was the result not of a conquest, but of the inability of the citizens of Islam’s second greatest city to control their factional feuding and concentrate on rebuilding in the aftermath of the destruction wrought by earthquake and marauders.

Attar, in other words, knew the greatness of Nishapur only through the vast post-apocalyptic landscape that occupied several square kilometers outside the eastern wall of Shadyakh. While it is probably true that he followed the trade of a druggist, as implied by the name Attar, there is specific mention that in 1158 Nishapur’s Street of the Druggists, where it is likely that Attar’s father had a shop, was deliberately burned down. When we think of Attar’s childhood, in other words, the image that should come to mind is not that of a lad growing up in a stable society and learning an honorable trade from his well-to-do father, but of the refugee children from Afghanistan and Syria who have shown us the human face of despair in recent decades.

Figure 4. Approximate area of Old Nishapur that was still occupied during Attar’s lifetime. Image courtesy of the author.