PDF

Download

Citations

Click and drag then release to select a passage to cite.

Annotations

How to submit annotations to Mizan Journal articles:

your work is published.

Search within

Editor’s Introduction

Image

Audio

Video

Chart or Graph

Editor’s Introduction

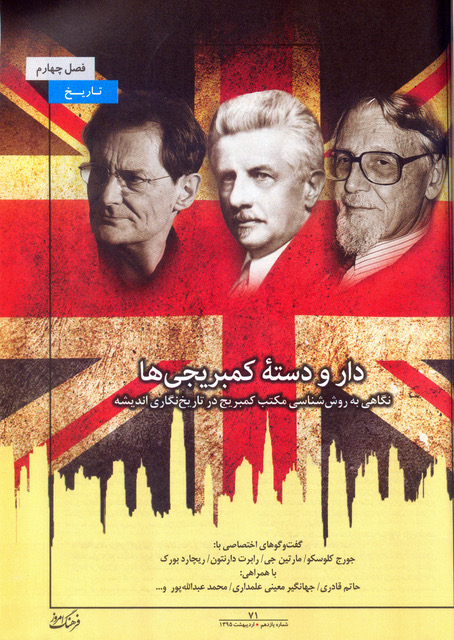

In an interview on the reception of the Cambridge School in 2016, Hatam Ghaderi,1 an Iranian political scientist, argued that the popularity of contextualism, in spite of its conservative underpinning, augured well for the current political debates in Iran. Contextualism invites readers to focus on language in context, he explained, thereby avoiding the kind of vaporous philosophizing and overindulgence in coining words seen at times in the French and German philosophical traditions, and most notably in the oracular obscurities of some of Heidegger’s acolytes.2 He envisaged that by espousing the underlying tenets of the Cambridge School, much needed clarity would be brought into the often tortuously argued and ill-defined philosophical debates that arise when various European philosophies travel to Iran.3 His interview is only one sample of current debates, by no means confined to Iran, on the relative merits of different methods and strategies for evaluating traditions of political thought, exemplifying a renewed interest in intellectual history.

The articles in this online colloquium examine that new interest as well as appropriations of past political thought bearing on Iran in the works of contemporary authors from a variety of linguistic traditions and historical settings, including India, the Arab world, and Iran itself. The emphasis is on the global context of modern thought. In translocal debates as well as those occasioned by intellectual traditions further afield, contemporary thinkers engage with a wider historical and ideational context. Can contextualism as method yield fruit outside of its original context, the upholding of which lies at the heart of European intellectual history?4 Focusing on a variety of thinkers and political concepts, the essays explore strategies of appropriation that define modern reevaluations of past thought, and the far reaching consequences of the new global context that has radically altered political debate and its ability to shape and direct political change. What is to be learnt from reading pre-global political thought in a global context?

Alexander Nachman’s “Quentin Skinner beh Fārsī: A Contextualist Reckoning with Islamic Protestantism” is the first article posted in the forum. It scrutinizes the variegated engagements with Skinnerian contextualism in the Iranian public sphere on the question of Islamic Protestantism—the quest for a liberal, or at least progressive kernel on the basis of which a new, improved iteration of Islam could emerge.

Four more articles will be added to the forum in the coming months. Urs Gösken examines the reception of David Hume’s Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, which came to the attention of Iranian intellectuals and activists in the nineteenth century. Gösken’s emphasis is on the influence of Hume on politico-religious debates in the Iranian scene and elsewhere in the Muslim world. Specifically, it deals with what has become known as the two-tiered outlook on religion that divides religious thought and practice into “popular” and “intellectual” and the adoption and adaptation of this particular aspect of Hume’s concept of religion.

Jens Hannsen’s contribution considers the forging of intellectual lineages when two twentieth century philosophers—Ernst Bloch and Husayn Muruwwa—penned essays on the elective affinities between Abbasid-Andalusian philosophy and Marxism, connecting among others Aristotle, Avicenna and Friedrich Engels. Hannsen claims that this intellectual lineage offers new dialectical perspectives on current conventions in Islamic Studies as well as debates the concept of identity in “Judeo-Christian civilization” and “Islam in Europe.”

Interest is commonly seen as the fundamental unit of liberal politics, writes Faisal Devji. He studies how Gandhi and Iqbal, Savarkar and Jinnah were part of a conversation on the apparent ‘lack’ or limitation of interest in Indian politics. For these men it was the absence of interest as a foundational category in Indian society, attributed to the fact that property did not define social relations there, that made for its violence as much as spiritualism. Their problem was either to create interests where they didn’t exist, or to dispense with them altogether.

Furthermore, the debate on interest in Indian politics drew from a variety of founts, European in origin and otherwise. The emphasis in this article is on the Perso-Islamic residues that configured prominently in writings of various participants in this debate. How was the absence of interest in Indian politics historicized?

Notes

All digital content cited in this article was accessed on or before July 22, 2020.

- https://www.modares.ac.ir/~ghaderyh ↑

- Muhammad Taqi Shari‘ati, “Dar miyan-i muhafizakari va tarikhnigari, musahabah ba Hatam Gharderi,” Farhang Emruz 11 (2016), pp. 79-82. ↑

- For more on the trajectory of early translations of European philosophical texts, see Roman Seidel, “Early Translations of Modern European Philosophy: On the Significance of an Under-Researched Phenomenon for the Study of Modern Iranian Intellectual History,” in Iran’s Constitutional Revolution of 1906 and Narratives of the Enlightenment, ed. Ali Ansari (London: Ginko Library, 2016), pp. 207-229. ↑

- For an insightful critique of “first context,” see Peter F. Gordon, “Contextualism and Criticism in the History of Ideas,” in Rethinking Modern European Intellectual History, Darrin M. McMahon and Samuel Moyn, eds (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), pp. 32-55, esp. pp. 37-9. ↑

Editor’s Introduction

In an interview on the reception of the Cambridge School in 2016, Hatam Ghaderi,1 an Iranian political scientist, argued that the popularity of contextualism, in spite of its conservative underpinning, augured well for the current political debates in Iran. Contextualism invites readers to focus on language in context, he explained, thereby avoiding the kind of vaporous philosophizing and overindulgence in coining words seen at times in the French and German philosophical traditions, and most notably in the oracular obscurities of some of Heidegger’s acolytes.2 He envisaged that by espousing the underlying tenets of the Cambridge School, much needed clarity would be brought into the often tortuously argued and ill-defined philosophical debates that arise when various European philosophies travel to Iran.3 His interview is only one sample of current debates, by no means confined to Iran, on the relative merits of different methods and strategies for evaluating traditions of political thought, exemplifying a renewed interest in intellectual history.

The articles in this online colloquium examine that new interest as well as appropriations of past political thought bearing on Iran in the works of contemporary authors from a variety of linguistic traditions and historical settings, including India, the Arab world, and Iran itself. The emphasis is on the global context of modern thought. In translocal debates as well as those occasioned by intellectual traditions further afield, contemporary thinkers engage with a wider historical and ideational context. Can contextualism as method yield fruit outside of its original context, the upholding of which lies at the heart of European intellectual history?4 Focusing on a variety of thinkers and political concepts, the essays explore strategies of appropriation that define modern reevaluations of past thought, and the far reaching consequences of the new global context that has radically altered political debate and its ability to shape and direct political change. What is to be learnt from reading pre-global political thought in a global context?

Alexander Nachman’s “Quentin Skinner beh Fārsī: A Contextualist Reckoning with Islamic Protestantism” is the first article posted in the forum. It scrutinizes the variegated engagements with Skinnerian contextualism in the Iranian public sphere on the question of Islamic Protestantism—the quest for a liberal, or at least progressive kernel on the basis of which a new, improved iteration of Islam could emerge.

Four more articles will be added to the forum in the coming months. Urs Gösken examines the reception of David Hume’s Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, which came to the attention of Iranian intellectuals and activists in the nineteenth century. Gösken’s emphasis is on the influence of Hume on politico-religious debates in the Iranian scene and elsewhere in the Muslim world. Specifically, it deals with what has become known as the two-tiered outlook on religion that divides religious thought and practice into “popular” and “intellectual” and the adoption and adaptation of this particular aspect of Hume’s concept of religion.

Jens Hannsen’s contribution considers the forging of intellectual lineages when two twentieth century philosophers—Ernst Bloch and Husayn Muruwwa—penned essays on the elective affinities between Abbasid-Andalusian philosophy and Marxism, connecting among others Aristotle, Avicenna and Friedrich Engels. Hannsen claims that this intellectual lineage offers new dialectical perspectives on current conventions in Islamic Studies as well as debates the concept of identity in “Judeo-Christian civilization” and “Islam in Europe.”

Interest is commonly seen as the fundamental unit of liberal politics, writes Faisal Devji. He studies how Gandhi and Iqbal, Savarkar and Jinnah were part of a conversation on the apparent ‘lack’ or limitation of interest in Indian politics. For these men it was the absence of interest as a foundational category in Indian society, attributed to the fact that property did not define social relations there, that made for its violence as much as spiritualism. Their problem was either to create interests where they didn’t exist, or to dispense with them altogether.

Furthermore, the debate on interest in Indian politics drew from a variety of founts, European in origin and otherwise. The emphasis in this article is on the Perso-Islamic residues that configured prominently in writings of various participants in this debate. How was the absence of interest in Indian politics historicized?

Notes

All digital content cited in this article was accessed on or before July 22, 2020.

- https://www.modares.ac.ir/~ghaderyh ↑

- Muhammad Taqi Shari‘ati, “Dar miyan-i muhafizakari va tarikhnigari, musahabah ba Hatam Gharderi,” Farhang Emruz 11 (2016), pp. 79-82. ↑

- For more on the trajectory of early translations of European philosophical texts, see Roman Seidel, “Early Translations of Modern European Philosophy: On the Significance of an Under-Researched Phenomenon for the Study of Modern Iranian Intellectual History,” in Iran’s Constitutional Revolution of 1906 and Narratives of the Enlightenment, ed. Ali Ansari (London: Ginko Library, 2016), pp. 207-229. ↑

- For an insightful critique of “first context,” see Peter F. Gordon, “Contextualism and Criticism in the History of Ideas,” in Rethinking Modern European Intellectual History, Darrin M. McMahon and Samuel Moyn, eds (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), pp. 32-55, esp. pp. 37-9. ↑