PDF

Download

Citations

Click and drag then release to select a passage to cite.

Annotations

How to submit annotations to Mizan Journal articles:

your work is published.

Search within

From Skeptical Theism to Materialist Atheism

Mirza Fath ‘Ali Akhundzadeh’s Reception of David Hume’s Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion

Image

Audio

Video

Chart or Graph

From Skeptical Theism to Materialist Atheism

Mirza Fath ‘Ali Akhundzadeh’s Reception of David Hume’s Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion

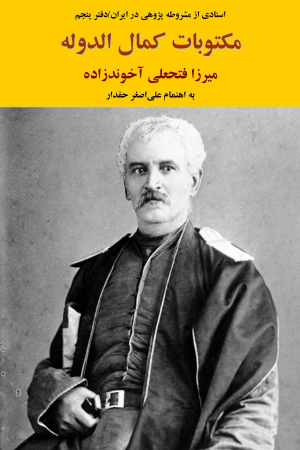

Left: Photograph of Mirza Fath ‘Ali Akhundzadeh. Public domain image from Wikimedia via the Institute of Manuscripts of Azerbaijan. Right: Allan Ramsay, Portrait of David Hume, 1754. Public domain image from Wikimedia via the Scottish National Portrait Gallery.

Beginning in the 19th century, the philosophy of David Hume (1711-76), empiricist skeptic and one of the main representatives of the Scottish Enlightenment, occasioned a variegated reception in the Islamic world. The main subject of these public debates was Hume’s often interconnected philosophical concerns, such as the onto-epistemological status of causality, the possibility of metaphysics and the existence of God and its proof. Given this rich history, the present contribution must appear limited, both in terms of time span and thematic scope. In fact, it is limited to an early example for the appropriation of Hume’s thought in the Islamic world, the reaction of 19th century Iranian reformist thinker Mirza Fath ‘Ali Akhundzadeh (Mīrzā Fatḥ ʿAlī Āḫūnd-zāda, 1812-78),1 famous Iranian nationalist cum atheist who in his own ideational context, engaged with the question of God’s existence in light of Hume’s arguments in his posthumously published Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion. The emphasis in this study is on Akhundzadeh’s repurposing of Hume’s thought in support of his own views on atheism and materialism.

Title page of Concerning Natural Religion, 2nd edition, 1779. Public domain image via Wikimedia.

Hume’s Dialogues: From Skeptical Theism…

Given Hume’s skeptical empiricism, it comes as no surprise that the problem of metaphysics in general and – more particularly – the question of God’s essence and existence constitute recurring themes in his philosophical oeuvre. He began work on the Dialogues in 1750, but the book was not published before he died. In form and partially in content, Dialogues draws inspiration from Cicero’s On the Nature of the Gods. Hume’s Dialogues are subdivided into 12 parts that pertain to the essence, rather than the existence, of God.

Participants in the discussion in parts 1 to 11 include, DEMEA, an orthodox scholastic who advocates a cosmological argument for the existence of God, CLEANTHES the Stoic who, invoking the creationist argument of intelligent design, holds that God’s essence must be understood in analogy to the human mind, and PHILO, an empiricist skeptic and hence, arguably, Hume’s alter ego, who maintains that man’s cognitive constitution is conducive solely to the material realm and therefore unable to lay claim to certainty on what is metaphysical.

Both PHILO and DEMEA denounce CLEANTHES’ conception of God as anthropomorphic, albeit for different reasons. PHILO further challenges it on the grounds that creation, more than to an intelligently designed apparatus, displays analogy to a living organism to which the laws of vegetation and generation, rather than of craftmanship, apply. At the end of Part 11, DEMEA, outwitted by what the other two discussants bring forth and suspecting PHILO of atheism, quits the debate, leaving CLEANTHES and PHILO to conclude the discussion in Part 12.

DEMEA’s departure, of course, may be understood as symbolizing the intellectual collapse of scholasticism, brought about in the Dialogues by CLEANTHES’ and PHILO’s successful confutation of the cosmological argument for the existence of God. As formulated by DEMEA, the argument echoes Ibn Sina’s (Ibn Sīnā’s, d. 1037) ontological claim that in order to avoid the absurd assumption of an infinite chain of cause and effect, God is the one necessary existent which is the first cause for the merely contingent existence of all entities other than himself.

Against this argument, CLEANTHES reasons that, first, man’s cognitive faculties cannot demonstrate that it is as necessary for God to exist as it is for 2 plus 2 to equal 4, and that, second, there is no ineluctable argument against positing matter, rather than God, as the necessarily existent being. PHILO, on his part, cautions against introducing the idea of necessity into any discussion on God’s essence in the first place. For just as the existence of the regularities we observe in mathematics is necessary in the sense that they result from laws internal to mathematics itself, and not in the sense that they have been produced by some necessary external cause, likewise the existence of the material universe can be conceived of as necessary by virtue of itself alone.

After DEMEA’s scholastic theism has thus been disproved, PHILO reveals that he too advocates theism, but not the scholastic variety, and that all his previous reasoning against DEMEA had not been aimed at making a case for atheism, but rather at highlighting the invalidity of scholasticism’s cosmological demonstration of God’s existence. As for his difference with CLEANTHES, he declares that in the final analysis, it is merely verbal. For neither an advocate of God’s transcendence nor a follower of God’s analogous similarity to man can come up with any unchallengeable standard measure by which to determine either transcendence or similarity.

Consequently, PHILO ends up commending philosophically, not theologically grounded theism. This he calls the “natural” religion – “natural” because it does justice to both the nature of God and the nature of man. And he does not consider his own philosophical skepticism as antagonistic to religious belief—quite to the contrary: it is the very acknowledgment of man’s intellectual imperfection that makes man humble enough to remain open to revealed truth, whereas a scholastic dogmatist, considering all metaphysical questions settled, has closed his heart to it.

Fathali Akhundzadeh, the author of the treatise Maktobat. Design by Afshin Sobuki. Image via the BBC.

… to Materialist Atheism: Akhundzadeh’s Elaborations on Hume’s Dialogues

Familiarity, however fragmentary, selective or indirect, of Akhundzadeh with Hume’s Dialogues may be surmised in two of his writings: his Maqālāt that contains a text titled Rescript from Hume, presented as a letter from Hume to the Muslim religious scholars of India; and the appendix to his Maktūbāt that contains, as part of one of the fictitious letters exchanged between two – likewise fictitious – correspondents, the same text, slightly abbreviated and most importantly,lacking any reference to or mention of David Hume. As to Hume’s alleged letter, there is no record of such correspondence in his edited oeuvre, which invites the suggestion that it too is a figment of Akhundzadeh’s imagination.

The argument presented there as well as in the version appended to the Maktūbāt constitutes a complete refutation of the cosmological argument for the existence of God. Rather interestingly, it is crafted as a theological discourse with no reference to its philosophical origin in Ibn Sina’s ontology. In fact, it was this element of Ibn Sina’s doctrine that was appropriated by Islamic scholasticism, and Akhundzadeh himself, considering his early career as a religious scholar, must have internalized it as a theological argument.

The “religious scholars of India”, then, in the spurious letter ascribed to Hume, are assigned the same role in the debate as that of DEMEA in Hume’s Dialogues. As for the other two disputants in the Dialogues, PHILO and CLEANTHES, neither of these names appears in Akhundzadeh’s texts. Instead, we find only one antagonist to the position ascribed to the Muslim religious scholars. In Hume’s letter, he is identified as the sender and, in the appendix to the Maktūbāt as a friend of a certain Kamal al-Dawla, one of the two fictitious correspondents in the initial edition of the Maktūbāt. The position advocated by this sole antagonist corresponds to the objections raised by CLEANTHES and seconded by PHILO, against the cosmological argument defended by DEMEA in Hume’s Dialogues.

Moreover, it also includes the vegetation and generation argument, which in Hume’s Dialogues is brought by PHILO against CLEANTHES in a context unrelated to the dispute over the cosmological argument. In Akhundzadeh’s writings, however, it is presented as yet another objection against the cosmological argument in opposition to the Muslim religious scholars. Now, CLEANTHES’ objections, in Hume’s Dialogues against the cosmological argument that posits God as the necessarily existent being, alternatively posit matter as the necessarily existent being. In Hume’s Dialogues, though, this is done only to demonstrate that the cosmological argument falls short of proving God’s existence. Neither CLEANTHES nor even PHILO the skeptic argue against DEMEA to make a case for materialism or atheism, although, in the case of PHILO, this does not become clear before Part 12. Akhundzadeh, on the other, employs all these arguments to prioritize materialism and atheism over metaphysical theism.

Akhundzadeh’s portrayal of the antagonists to the cosmological argument as atheists suggests that either he himself or the previous recipients of Hume’s Dialogues on whom he drew for his own text did not consider any aspect of Hume’s text other than the refutation of the cosmological argument. Significantly, the thinkers invoked as intellectual witnesses in Akhundzadeh’s texts are, in Hume’s “letter”, referred to as “naturalists”, i.e. thinkers denying or at least questioning the reality of anything beyond the physical, and, in the appendix to the Maktūbāt, as “philosophers”. This terminological equation goes to show that to Akhundzadeh, only non-metaphysical thinkers such as atheists qualify as philosophers. This observation, in turn, with regard to reception history suggests that Akhundzadeh drew on Russian sources. Of course, this is also likely because he did not know any other Western language. It becomes even more likely if we consider that the reception of Hume’s philosophy in Russia was as a destructive skeptic, nay an atheist and a threat to orthodoxy.

It is highly likely that Akhundzadeh was aware of Russian antagonism to Humean thought, but nevertheless evaluated it in a positive sense. Whatever the case may be, Akhundzadeh’s appropriation of Hume is significant because, in Iranian intellectual history, it constitutes an early example of materialism, of a materialism, to note, different from and independent of dialectical and historical materialism that were to become so popular among the left a few decades later. For, in dialectical materialism, matter is posited as the ultimate onto-epistemological principle in lieu of Hegel’s “Geist”. In the type of materialism presented by Akhundzadeh and attributed to Hume, matter is posited as the necessarily existent being in lieu of God, as conceived of by Muslim philosophers and theologians.

In what may be considered as the intellectual foundation of what Akhundzadeh advertised as “Protestantism,” he transposed the necessarily existent being cum first cause from the metaphysical to the physical realm. The line of argumentation Akhundzadeh adopted came to enjoy a long career among leftist thinkers throughout the Islamic world, and still enjoys a widespread following today. Its invocation in the Syrian philosopher Ṣādeq Jalāl al-ʿAẓm’s (d. 2016) Critique of Religious Thought is a case in point.

Following the refutation of the cosmological argument for the existence of God in Akhundzadeh’s Maktūbāt, there comes a remark that may incline us to reconsider whether his materialism spells atheism. For in the midst of a long passage where he pontificates on the incompatibility of theism with modern science, he writes: “Happy is the person who can reconcile these two contradictory positions within himself! But I think that it must be ruled out.” Here, Akhundzadeh stops short of declaring that the incompatibility of religion with science is an objective fact, and only claims that it is a proposition that he subjectively finds to be unfathomable. It may also be likely that Akhundzadeh the alleged atheist, following in the footsteps of PHILO the skeptic in Hume’s Dialogues, had not closed his heart to revelation either. If our quote from Akhundzadeh is regarded as weighty enough to allow us to qualify our verdict on him as an atheist, then we are confronted with an ironic twist of entangled intellectual history: for irrespective of all the condemnation he drew in his lifetime for being an atheist, Hume repeatedly insisted that, in real life, there can never be a full atheist.

Notes

1 For Akhundzadeh’s biography see, Hamid Algar, “Āḳūndzāda,” Encyclopaedia Iranica Online, https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-iranica-online/*-COM_5031.

From Skeptical Theism to Materialist Atheism

Mirza Fath ‘Ali Akhundzadeh’s Reception of David Hume’s Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion

Left: Photograph of Mirza Fath ‘Ali Akhundzadeh. Public domain image from Wikimedia via the Institute of Manuscripts of Azerbaijan. Right: Allan Ramsay, Portrait of David Hume, 1754. Public domain image from Wikimedia via the Scottish National Portrait Gallery.

Beginning in the 19th century, the philosophy of David Hume (1711-76), empiricist skeptic and one of the main representatives of the Scottish Enlightenment, occasioned a variegated reception in the Islamic world. The main subject of these public debates was Hume’s often interconnected philosophical concerns, such as the onto-epistemological status of causality, the possibility of metaphysics and the existence of God and its proof. Given this rich history, the present contribution must appear limited, both in terms of time span and thematic scope. In fact, it is limited to an early example for the appropriation of Hume’s thought in the Islamic world, the reaction of 19th century Iranian reformist thinker Mirza Fath ‘Ali Akhundzadeh (Mīrzā Fatḥ ʿAlī Āḫūnd-zāda, 1812-78),1 famous Iranian nationalist cum atheist who in his own ideational context, engaged with the question of God’s existence in light of Hume’s arguments in his posthumously published Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion. The emphasis in this study is on Akhundzadeh’s repurposing of Hume’s thought in support of his own views on atheism and materialism.

Title page of Concerning Natural Religion, 2nd edition, 1779. Public domain image via Wikimedia.

Hume’s Dialogues: From Skeptical Theism…

Given Hume’s skeptical empiricism, it comes as no surprise that the problem of metaphysics in general and – more particularly – the question of God’s essence and existence constitute recurring themes in his philosophical oeuvre. He began work on the Dialogues in 1750, but the book was not published before he died. In form and partially in content, Dialogues draws inspiration from Cicero’s On the Nature of the Gods. Hume’s Dialogues are subdivided into 12 parts that pertain to the essence, rather than the existence, of God.

Participants in the discussion in parts 1 to 11 include, DEMEA, an orthodox scholastic who advocates a cosmological argument for the existence of God, CLEANTHES the Stoic who, invoking the creationist argument of intelligent design, holds that God’s essence must be understood in analogy to the human mind, and PHILO, an empiricist skeptic and hence, arguably, Hume’s alter ego, who maintains that man’s cognitive constitution is conducive solely to the material realm and therefore unable to lay claim to certainty on what is metaphysical.

Both PHILO and DEMEA denounce CLEANTHES’ conception of God as anthropomorphic, albeit for different reasons. PHILO further challenges it on the grounds that creation, more than to an intelligently designed apparatus, displays analogy to a living organism to which the laws of vegetation and generation, rather than of craftmanship, apply. At the end of Part 11, DEMEA, outwitted by what the other two discussants bring forth and suspecting PHILO of atheism, quits the debate, leaving CLEANTHES and PHILO to conclude the discussion in Part 12.

DEMEA’s departure, of course, may be understood as symbolizing the intellectual collapse of scholasticism, brought about in the Dialogues by CLEANTHES’ and PHILO’s successful confutation of the cosmological argument for the existence of God. As formulated by DEMEA, the argument echoes Ibn Sina’s (Ibn Sīnā’s, d. 1037) ontological claim that in order to avoid the absurd assumption of an infinite chain of cause and effect, God is the one necessary existent which is the first cause for the merely contingent existence of all entities other than himself.

Against this argument, CLEANTHES reasons that, first, man’s cognitive faculties cannot demonstrate that it is as necessary for God to exist as it is for 2 plus 2 to equal 4, and that, second, there is no ineluctable argument against positing matter, rather than God, as the necessarily existent being. PHILO, on his part, cautions against introducing the idea of necessity into any discussion on God’s essence in the first place. For just as the existence of the regularities we observe in mathematics is necessary in the sense that they result from laws internal to mathematics itself, and not in the sense that they have been produced by some necessary external cause, likewise the existence of the material universe can be conceived of as necessary by virtue of itself alone.

After DEMEA’s scholastic theism has thus been disproved, PHILO reveals that he too advocates theism, but not the scholastic variety, and that all his previous reasoning against DEMEA had not been aimed at making a case for atheism, but rather at highlighting the invalidity of scholasticism’s cosmological demonstration of God’s existence. As for his difference with CLEANTHES, he declares that in the final analysis, it is merely verbal. For neither an advocate of God’s transcendence nor a follower of God’s analogous similarity to man can come up with any unchallengeable standard measure by which to determine either transcendence or similarity.

Consequently, PHILO ends up commending philosophically, not theologically grounded theism. This he calls the “natural” religion – “natural” because it does justice to both the nature of God and the nature of man. And he does not consider his own philosophical skepticism as antagonistic to religious belief—quite to the contrary: it is the very acknowledgment of man’s intellectual imperfection that makes man humble enough to remain open to revealed truth, whereas a scholastic dogmatist, considering all metaphysical questions settled, has closed his heart to it.

Fathali Akhundzadeh, the author of the treatise Maktobat. Design by Afshin Sobuki. Image via the BBC.

… to Materialist Atheism: Akhundzadeh’s Elaborations on Hume’s Dialogues

Familiarity, however fragmentary, selective or indirect, of Akhundzadeh with Hume’s Dialogues may be surmised in two of his writings: his Maqālāt that contains a text titled Rescript from Hume, presented as a letter from Hume to the Muslim religious scholars of India; and the appendix to his Maktūbāt that contains, as part of one of the fictitious letters exchanged between two – likewise fictitious – correspondents, the same text, slightly abbreviated and most importantly,lacking any reference to or mention of David Hume. As to Hume’s alleged letter, there is no record of such correspondence in his edited oeuvre, which invites the suggestion that it too is a figment of Akhundzadeh’s imagination.

The argument presented there as well as in the version appended to the Maktūbāt constitutes a complete refutation of the cosmological argument for the existence of God. Rather interestingly, it is crafted as a theological discourse with no reference to its philosophical origin in Ibn Sina’s ontology. In fact, it was this element of Ibn Sina’s doctrine that was appropriated by Islamic scholasticism, and Akhundzadeh himself, considering his early career as a religious scholar, must have internalized it as a theological argument.

The “religious scholars of India”, then, in the spurious letter ascribed to Hume, are assigned the same role in the debate as that of DEMEA in Hume’s Dialogues. As for the other two disputants in the Dialogues, PHILO and CLEANTHES, neither of these names appears in Akhundzadeh’s texts. Instead, we find only one antagonist to the position ascribed to the Muslim religious scholars. In Hume’s letter, he is identified as the sender and, in the appendix to the Maktūbāt as a friend of a certain Kamal al-Dawla, one of the two fictitious correspondents in the initial edition of the Maktūbāt. The position advocated by this sole antagonist corresponds to the objections raised by CLEANTHES and seconded by PHILO, against the cosmological argument defended by DEMEA in Hume’s Dialogues.

Moreover, it also includes the vegetation and generation argument, which in Hume’s Dialogues is brought by PHILO against CLEANTHES in a context unrelated to the dispute over the cosmological argument. In Akhundzadeh’s writings, however, it is presented as yet another objection against the cosmological argument in opposition to the Muslim religious scholars. Now, CLEANTHES’ objections, in Hume’s Dialogues against the cosmological argument that posits God as the necessarily existent being, alternatively posit matter as the necessarily existent being. In Hume’s Dialogues, though, this is done only to demonstrate that the cosmological argument falls short of proving God’s existence. Neither CLEANTHES nor even PHILO the skeptic argue against DEMEA to make a case for materialism or atheism, although, in the case of PHILO, this does not become clear before Part 12. Akhundzadeh, on the other, employs all these arguments to prioritize materialism and atheism over metaphysical theism.

Akhundzadeh’s portrayal of the antagonists to the cosmological argument as atheists suggests that either he himself or the previous recipients of Hume’s Dialogues on whom he drew for his own text did not consider any aspect of Hume’s text other than the refutation of the cosmological argument. Significantly, the thinkers invoked as intellectual witnesses in Akhundzadeh’s texts are, in Hume’s “letter”, referred to as “naturalists”, i.e. thinkers denying or at least questioning the reality of anything beyond the physical, and, in the appendix to the Maktūbāt, as “philosophers”. This terminological equation goes to show that to Akhundzadeh, only non-metaphysical thinkers such as atheists qualify as philosophers. This observation, in turn, with regard to reception history suggests that Akhundzadeh drew on Russian sources. Of course, this is also likely because he did not know any other Western language. It becomes even more likely if we consider that the reception of Hume’s philosophy in Russia was as a destructive skeptic, nay an atheist and a threat to orthodoxy.

It is highly likely that Akhundzadeh was aware of Russian antagonism to Humean thought, but nevertheless evaluated it in a positive sense. Whatever the case may be, Akhundzadeh’s appropriation of Hume is significant because, in Iranian intellectual history, it constitutes an early example of materialism, of a materialism, to note, different from and independent of dialectical and historical materialism that were to become so popular among the left a few decades later. For, in dialectical materialism, matter is posited as the ultimate onto-epistemological principle in lieu of Hegel’s “Geist”. In the type of materialism presented by Akhundzadeh and attributed to Hume, matter is posited as the necessarily existent being in lieu of God, as conceived of by Muslim philosophers and theologians.

In what may be considered as the intellectual foundation of what Akhundzadeh advertised as “Protestantism,” he transposed the necessarily existent being cum first cause from the metaphysical to the physical realm. The line of argumentation Akhundzadeh adopted came to enjoy a long career among leftist thinkers throughout the Islamic world, and still enjoys a widespread following today. Its invocation in the Syrian philosopher Ṣādeq Jalāl al-ʿAẓm’s (d. 2016) Critique of Religious Thought is a case in point.

Following the refutation of the cosmological argument for the existence of God in Akhundzadeh’s Maktūbāt, there comes a remark that may incline us to reconsider whether his materialism spells atheism. For in the midst of a long passage where he pontificates on the incompatibility of theism with modern science, he writes: “Happy is the person who can reconcile these two contradictory positions within himself! But I think that it must be ruled out.” Here, Akhundzadeh stops short of declaring that the incompatibility of religion with science is an objective fact, and only claims that it is a proposition that he subjectively finds to be unfathomable. It may also be likely that Akhundzadeh the alleged atheist, following in the footsteps of PHILO the skeptic in Hume’s Dialogues, had not closed his heart to revelation either. If our quote from Akhundzadeh is regarded as weighty enough to allow us to qualify our verdict on him as an atheist, then we are confronted with an ironic twist of entangled intellectual history: for irrespective of all the condemnation he drew in his lifetime for being an atheist, Hume repeatedly insisted that, in real life, there can never be a full atheist.

Notes

1 For Akhundzadeh’s biography see, Hamid Algar, “Āḳūndzāda,” Encyclopaedia Iranica Online, https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-iranica-online/*-COM_5031.