PDF

Download

Citations

Click and drag then release to select a passage to cite.

Annotations

How to submit annotations to Mizan Journal articles:

your work is published.

Search within

Interests and Ideas

Image

Audio

Video

Chart or Graph

Interests and Ideas

Whether by scholars, journalists, politicians or indeed participants in some riot, caste, religious, gender and other supposedly traditional forms of conflict in India tend to be seen in very similar ways. However simple or complex the explanation proffered, such conflict is understood as being made up of inherited prejudices and repackaged sentiments, both embedded within a changing structure of social or economic relations. True or false as these analyses may be, interesting is their ubiquitous character as a kind of common sense. Whatever their differences, after all, these accounts rarely integrate such conflict into any conceptual framework. At most it is attributed to everyday political instrumentality, with otherwise latent religious views being exploited for electoral or commercial purposes by unscrupulous officials, hand in hand with criminals and local youth organizations.1

Emerging in colonial times, such explanations are linked to what Bernard S. Cohn called an imperial sociology of knowledge, in which the social sciences as they came to be known were deployed to make sense of conflict, if only with a view to control it.2 As actual or would-be instruments of the British and later Indian government, these accounts were never meant to address religious and other conflict as anything other than a problem, and not by considering it in conceptual or normative terms as political thought. Ironically, it was the older language of orientalist scholarship in the 18th and early 19th centuries, as well as that of religious debate and missionary activity during this period, that stood alone in taking these enmities seriously, rather than seeing them merely as examples of social dysfunction or the epiphenomena of economic struggles, to say nothing about the ambitions of strongmen.

While there have been a few excellent studies, mostly anthropological, that exit a colonial sociology of knowledge in exploring the local languages and internal logics of apparently primordial conflict in India,3 I am interested in the making of a new political vocabulary to understand it. In particular, I shall be occupied with the way in which figures like M.K. Gandhi and Mohammad Iqbal sought to remake the political language of their country. They did so by radicalizing a classically imperialist argument, that Indian politics was marked not by its lack of independence so much as of ideas and principles, and it was this situation that made British rule possible as well as necessary. The apparently ceaseless and inevitable animosity between religious and other groups there was said to require the presence of a foreign power to keep the peace between them.

Although there were many ideas and principles that Indians supposedly lacked, among them individualism or the ability to separate political from religious life, it is the alleged absence of interest as a political category (but strangely not an economic one) that I am concerned with. On the one hand Indians were meant to be so consumed by a generally pecuniary form of self-interest that they were willing to stoop to the most brutal violence in order to achieve it, even if this meant putting the greater good of the country and so their own future at risk. But on the other, Indians seemed willing to sacrifice their interests and even lives in superstitious or fanatical actions that were as much religious as political. And if some of these actions could be attributed to ignorance and poverty, the participation in them of prosperous and educated Indians always rendered such distinctions ambiguous.

Interests come in different sizes and shapes, including various gradations of individual and collective identity, each of which may contradict the others. The problem supposedly posed by India’s simultaneously excessive and recessive interests had to do not with their plurality so much as irrationality, which is to say their counter-productive character. Given their great internal differences, for example, how might Hindus and Muslims constitute political interests, unless it was negatively or due to mutual and hereditary antipathies? Why were economic, regional or indeed truly national forms of collective life unable to compete with caste or religious ones? The answers to these questions also involved pointing to some absence, whether of education, administration or independence, and thus doing little more than doubling the colonial narrative of lack as a category constitutive of India’s political life.

Now the colonial state was not the only agency that promoted the idea that India’s politics was constituted by absence. Indians themselves did the same, trying to address this lack either by seeking to fill it with more “rational” class or national interests, or by claiming that such an absence was a positive one and marked India’s peculiar genius as opposed to that of Europe. Both of these approaches, of course, were apologetic ones, but they were also, as I have suggested, radicalized into a new kind of argument as part of a conversation between Indian thinkers and politicians from different parties and communities. We shall see that this conversation turned an old imperial argument into a new Indian one, not least because the colonial state was no longer part of it. Crucial, in other words, is that while learning from the West, this debate was not part of a dialogue with it.

While the English word interest was used by Indian political thinkers, it is also important to note that the term has no exact equivalent in Indian languages. The idea of self-interest, for instance, may be conveyed by the term swarth, more commonly selfishness, while that of advantage more generally might be called fayda or benefit. It is then the English original that allows one to make sense of such redefined Indian terms, whose multiplicity indicates another kind of absence or inability, perhaps even the refusal to constitute a complete or one-to-one translation of interest in its theoretical and political sense into Indian vernaculars. That this is not due to the ignorance of such an original is clear and calls for an explanation of the difference in linguistic usage. Provisionally it might be possible to suggest that this difference indicates the ambiguity with which the word continues to be invested.

Like his peers, Gandhi started with the premise that interests didn’t exist in India, or at least didn’t define social relations there. But unlike many of them, he typically reversed its political meaning. For instead of attributing India’s colonization to such a lack of national or even religious interest, the Mahatma argued that it was Indian self-interest that had in fact enabled British rule. In a chapter of his 1909 tract Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule, called “Why was India lost?” Gandhi blamed colonialism not on the force of arms but rather the mutual interests of the British and the Indians in commerce:

Some Englishmen state that they took, and they hold, India by the sword. Both these statements are wrong. The sword is entirely useless for holding India. […]. Then it follows that we keep the English in India for our base self-interest. We like their commerce, they please us by their subtle methods, and get what they want from us.4

For Gandhi, then, interest was primarily an economic rather than political category, and it therefore resulted not in resistance so much as an all too easy acquiescence to the lure of wealth and comfort. And this meant that if colonialism was to be defeated, interest had to be rejected for sacrifice and duty as their own reward. This was one aspect of his famous doctrine, taken from the Bhagavad-Gita, of desire-less action or forsaking ends for means. Gandhi imagined that since property was not the basis of Indian society, it was neither possible nor desirable to found Indian social relations on interest, and in fact argued that it was only the establishment of the colonial state as a neutral or third party between Indians that made some kind of interest possible, though in a very limited sense.

In other words, Indians were compelled to adopt the character of interest groups whenever they dealt with the colonial state, which, by constituting itself as a mediator between parties, sought to engineer and guarantee contractual relations among them. When speaking about the relations of Hindus and Muslims in particular, Gandhi often described this form of mediation, and its creation of contractual relations through the sole agency of the state, as a system of “divide and rule”. By this he didn’t necessarily mean that the British were deliberately fooling their naïve Indian subjects into quarreling with one another, but rather that the very structure of interest and contract was divisive by definition, because it set the state up as mediator and guarantor for interests that were not at all natural but decided by its workings.

In Hind Swaraj it was doctors and lawyers who exemplified the workings of the colonial state, and not only because their authority was accredited by this state. Doctors mediated between the patient and his own body, robbing him of any control over it by sedulously inducing a dependence on medication instead. In this way the swaraj or self-rule of the individual was destroyed even at the most intimate, corporeal level, and he became a mere cog in the system of imperialism, with its medical and pharmaceutical establishment itself supported by British capital and the greed for profits. As for lawyers, they separated both individuals and groups from each other by interposing the law as a mediator between Indians in such a way as to deprive them of any direct dealings with one another that might result in a friendly or at least mutually agreeable resolution of their disagreement. By delivering justice as a third party, the law instead made amicable resolution impossible, and indeed relied upon forced settlements that could only prolong and embitter the rivalry between individuals as much as communities.

Had the state managed to universalize interest and make of it the basis of all social relations, however, it might have served to pacify India if only in a thoroughly unjust and exploitative way. But the problem was that interest did not define most of the ways in which Indians dealt with each other, for the colonial state’s reach was not total and it could therefore only make interests of those who came before its institutions, the courts of law in particular. It was therefore the contradiction between the interests of colonial society on the one hand, and the religious and other ways in which Indians dealt with each other on the other, that made for conflict and violence. And if the reach of the state was limited, it was because interest and contract were ideas that required private property to constitute the basis of society, for it was this over which individuals and groups fought to define themselves as interests.

Gandhi thought that property could not constitute the basis of Indian society, and that interests could not therefore define its manifold relations. This was because most Indians had no property of any kind, something the Mahatma saw as both a curse and a blessing in disguise. After all the fact that property and so interests could not dominate Indian social relations meant that these latter, however oppressive they might otherwise be, could serve eventually to roll back and displace any political or economic order founded on property and its necessary inequalities. As was his wont, the Mahatma made the weakest and most vulnerable sections of Indian society into the vanguard of this non-violent revolution, a problematic instance of which can be seen in his correspondence with a female disciple, Raihana Tyabji, who had written him about the importance of securing women equal rights of inheritance:

Why should women have either to beg or to fight in order to win back their birthright? It is strange—and also tragically comic—to hear man born of woman talk loftily of ‘the weaker sex’ and nobly promising ‘to give’ us our due! What is this nonsense about ‘giving’? Where is the ‘nobility’ and ‘chivalry’ in restoring to people that which has been unlawfully wrested from them by those having brute power in their hands?5

Publishing her letter in the journal Young India on the 17th of October 1929, Gandhi responded to it by arguing that while he would never countenance unequal treatment of men and women under the law, Tyabji’s desire was nevertheless one that sought to expand the role of property in defining Indian social relations. Given the country’s poverty, however, the inclusion of women among property-owners could only be accomplished by further entrenching class differences in India:

But I am uncompromising in the matter of woman’s rights. In my opinion she should labour under no legal disability not suffered by man. […]. But to remove legal inequalities will be a mere palliative. The root of the evil lies much deeper than most people realize. […]. Man has always desired power. Ownership of property gives this power. Man hankers also after posthumous fame based on power. This cannot be had, if property is progressively cut up in pieces as it must be if all the posterity become equal co-sharers. Hence the descent of property for the most part on the eldest male issue. Most women are married. And they are co-sharers, in spite of the law being against them, in their husbands’ power and privileges. […]. Whilst therefore I would always advocate the repeal of all legal disqualifications, I should have the enlightened women of India to deal with the root cause. Woman is the embodiment of sacrifice and suffering, and her advent to public life should therefore result in purifying it, in restraining unbridled ambition and accumulation of property. Let them know that millions of men have no property to transmit to posterity. Let us learn from them that it is better for the few to have no ancestral property at all.6

Gandhi’s recommendation, that women emphasize their received and undoubtedly patriarchal role as embodiments of sacrifice to undo the dominance of property in social relations, was perhaps rather impractical, though of the same nature as the communist vision of the proletariat or the half-developed colonial world as, respectively, the vanguard and weakest link in the chain of capitalism. He gave the same advice to so-called “untouchables” as well, as recounted angrily by the low-caste leader Ambedkar.7

If all this tells us anything, it is that the Mahatma’s criticism of interest and its basis in property was a theoretical one, and not just directed at women or Dalits for prejudicial reasons. When he came to speak about religious conflict, Gandhi could draw upon a general theory in normative political terms. His ambition was to develop the disinterest or idealism embedded even in the most hierarchical and oppressive social relations to refashion them in a radical direction. His great experiment to do so was made during the Khilafat Movement in the immediate aftermath of the First World War, when Indian Muslims began to protest British and French moves to dismember the defeated Ottoman Empire.

Having contributed the bulk of India’s troops to the war, especially in the Middle East, and having been promised by the British prime minister that Muslim shrines and sanctities would not be interfered with, many Indian Muslims sought to have their sentiments respected as loyal subjects of the Empire. And it was to Gandhi that they turned for leadership in a movement that went on to become the first mass mobilisation in Indian history. Apart from seeing the justice of their claims and counselling a non-violent approach to the colonial state, the Mahatma was fascinated by the Khilafat Movement precisely because it was so difficult to construe it as an interest of any kind. Dedicated to the preservation of a foreign power, in whose support India’s Muslims expended great efforts and sent large amounts of money, the movement seemed to be a truly religious and therefore idealistic or disinterested one.

Because it was idealistic, or even fanatical and irrational, and not launched for an ulterior and therefore interested motive, as the British but also Hindu nationalists imagined, Gandhi thought the Khilafat could transform Indian politics more generally. Now there were many Hindus and Muslims, too, who sought to establish the movement on a contract and so interest, whereby the former’s support would be predicated upon the latter’s abandonment of cow-slaughter. But Gandhi steadfastly rejected such calls and wanted to base Hindu-Muslim unity upon the relations of love and sacrifice that he thought marked friendship or brotherhood as potentially if not always actually disinterested relations. This, rather than interest and contract, would secure India’s unity and freedom:

The test of friendship is assistance in adversity, and that too, unconditional assistance. Co-operation that needs consideration is a commercial contract and not friendship. Conditional co-operation is like adulterated cement which does not bind. It is the duty of the Hindus, if they see the justice of the Mahomedan cause, to render co-operation. If the Mahomedans feel themselves bound in honour to spare the Hindus’ feelings and to stop cow-killing, they may do so, no matter whether the Hindus co-operate with them or no. Though, therefore, I yield to no Hindu in my worship of the cow, I do not want to make the stopping of cow-killing a condition precedent to co-operation. Unconditional co-operation means the protection of the cow.8

Like Gandhi, Mohammad Iqbal, the pre-eminent Muslim poet and thinker of the 20th century, didn’t think a society based on interest was either possible or desirable in India. Thus in his presidential address of 1932 to the All-India Muslim Conference, Iqbal argued that the kind of democracy promoted by Indian nationalists was premised upon what he called the “money-economy of modern democracy”. Such a democratic order, in other words, rested upon the assumption that citizens were constituted of individual and self-owning voters for whom interests, too, were understood as properties to be defended. But this form of polity, Iqbal thought, was absolutely foreign to India’s peasant majority:

The present struggle in India is sometimes described as India’s revolt against the West. I do not think it is a revolt against the West; for the people of India are demanding the very institutions which the West stands for. Whether the gamble of elections, retinues of party leaders and hollow pageants of parliaments will suit a country of peasants for whom the money-economy of modern democracy is absolutely incomprehensible, is a different question altogether. Educated urban India demands democracy. The minorities, feeling themselves as distinct cultural units and fearing that their very existence is at stake, demand safeguards, which the majority community, for obvious reasons, refuses to concede. The majority community pretends to believe in a nationalism theoretically correct, if we start from Western premises, belied by facts, if we look to India. Thus the real parties to the present struggle in India are not England and India, but the majority community and the minorities of India which can ill-afford to accept the principle of Western democracy until it is properly modified to suit the actual conditions of life in India.9

Iqbal thought that Congress nationalism, with its focus on electorally-defined interests, had either naively or deliberately misread the nature of Indian society by describing it in supposedly univeral but in fact specifically European terms. And the repercussions of this misunderstanding, he imagined, were likely to be disastrous. Iqbal joined Gandhi in advocating not the creation of interests where they didn’t exist, but instead working to limit them. For he thought that India’s various groups and communities were defined not by property so much as ideals or principles, upon which structures of power, too, were built. However violent such ideals might occasionally be, Iqbal recognized them as extraordinary in their potential to make history out of spirit and principle, which is to say by the transcendental however defined.

While he thought that property had not yet come to define Indian social relations, then, Iqbal saw in nationalism private property writ large as communal ownership, and understood the nation-state as constituing its epitome as much as guarantor. By excluding the transcendent or ideal element of India’s existing social relations, and confining them in good liberal fashion to private life, the form of citizenship characteristic of nationalism ended up making public life entirely materialistic and violent in its instrumentality. The nation-state, in other words, professed to include and tolerate religious and other communities based on ideals, but in fact served to destroy or at least hollow them out. And communism, which Iqbal saw as Islam’s only rival as a global alternative to the existential violence of capitalism, he thought simply magnified the role of property in public life by giving it into the possession of the state. In a Marxist state, then, citizens were even more enslaved to property than in a capitalist one.

Iqbal’s task, then, was to retrieve the ideal or spiritual element in India’s social relations. But instead of doing so in Gandhi’s way, by magnifying everyday forms of disinterest or sacrifice into world-historical events, Iqbal remained true to his profession as a poet and philosopher by choosing a more intellectual path. In addition to protecting the apparently irrational aspects of inherited religious practice so as to forestall the domination of property and interest, as we have seen the Mahatma did by his encouragement of caste and gender-defined propertylessness, Iqbal strove to elaborate poetically upon the unpropertied social relations that he thought defined India. These he described as representing “invisible points of contact” between Hindus and Muslims in particular. Such relations were invisible not simply because they were increasingly hidden in the shadow of interests, but also due to the fact that visibility immediately rendered these communities into forms of ownership in which Muslims had to protect mosques from Hindu music while the latter protected cows from Muslim slaughter:

In view of the visible and invisible points of contact between the various communities of India I do believe in the possibility of constructing a harmonious whole whose unity cannot be disturbed by the rich diversity which it must carry within its bosom. The problem of ancient Indian thought was how the one became many without sacrificing its oneness. To-day this problem has come down from its ethical heights to the grosser plane of our political life, and we have to solve it in its reversed form, i.e., how the many can become one without sacrificing its plural character.10

Plurality was important for Iqbal not simply because he was concerned with the fate of minorities in India, but because ideals were necessarily and substantively different. In other words this was quite unlike a world defined by property, ownership and interest, which reduced multiplicity to a merely symbolic status in which, from the point of view of the nation-state as a third party, each difference had the same weight as and was substitutible with another. It was only by seeing Hindus and Muslims, or upper and lower castes, as mutually substitutible pairs, after all, however distinctive and unequal they might otherwise be, that they could become competitors as interest groups. Every piece of property, too, however distinctive, was comparable and so substitutible with any other, for they were equalized by being valued in monetary terms through contracts guaranteed by the state as itself a reified form of property. And it was this false intimacy of competition and substitution that Iqbal rejected by focussing on the real and unconvertible differences of all that was ideal, spiritual or principled.

Precisely because Muslims in India were a diverse and scattered minority, thought Iqbal, they were defined by ideals more than their co-religionists anywhere else in the world. As he put it in an address to the Muslim League in 1930:

It cannot be denied that Islam, regarded as an ethical ideal plus a certain kind of polity—by which expression I mean a social structure regulated by a legal system and animated by a specific ethical ideal—has been the chief formative factor in the life history of the Muslims of India. It has furnished those basic emotions and loyalties which gradually unify scattered individuals and groups and finally transform them into a well-defined people. Indeed it is no exaggeration to say that India is perhaps the only country in the world where Islam as a society is almost entirely due to the working of Islam as a culture inspired by a specific ethical ideal.11

And it was this spiritual sense of community that made Islam so vulnerable to nationalism as much as what he called religious adventurism in a 1934 article on the Ahmadi sect:

Islam repudiates the race idea altogether and founds itself on the religious idea alone. Since Islam bases itself on the religious idea alone, a basis which is wholly spiritual and consequently far more ethereal than blood relationship, Muslim society is naturally much more sensitive to forces which it considers harmful to its integrity.12

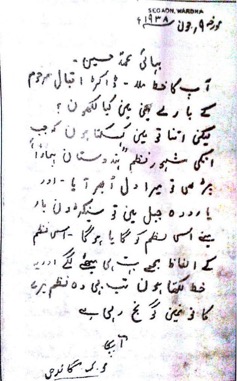

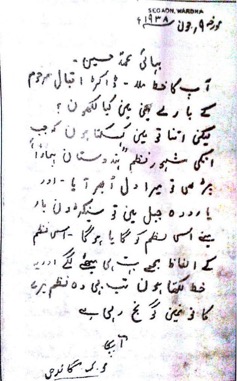

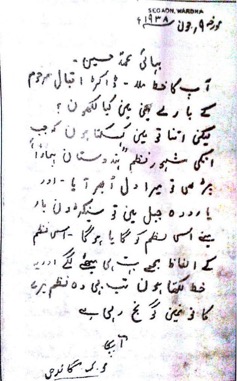

A letter in Urdu by Gandhi lamenting Muhammad Iqbal’s death and recalling the powerful impact of his memorable poem, 9 June 1938.

By deferring and delaying the advent of the nation-state, in recommending, for instance, India’s internal re-distribution into Hindu and Muslim dominated provinces, Iqbal tried to preserve not just the ideal foundation of Islam, but also the invisible points of contact that made up Indian social relations as a whole. And while his political solutions were of a rather negative kind, Iqbal also rehearsed these invisible relations in his poetry and philosophy, where Hindus and Muslims came to stand for metaphysical rather than sociological categories, being removed from the instrumentality of politics and so rendered unfit to become equivalents of one another.

A new political language or way of thinking emerged during the two or three decades leading up to India’s independence in 1947. While it started out by making use of colonial themes and categories, this form of thought quickly radicalised them into something quite novel. The received notion that Indian society was constituted by a series of lacks or absences, for example, and therefore subject to colonisation, was taken up if only to be turned into an idea beyond European recognition. The interests that Indians were supposed to possess either in excess or insufficiently came to provide political thinkers there with ways of reimagining their future. Gandhi and Iqbal tried to limit if not roll them back, attributing India’s religious and caste conflict precisely to the increasing dominance of property and so interests in public life.

Important about this debate was the fact that it managed to exit the largely instrumental and administrative categories of a colonial sociology of knowledge, locating as it did religious, caste and other ostensibly traditional relations within the normative arena of what I am calling political thought. And by taking leave of a narrative in which such relations could only figure as problems to be resolved, this conversation between Indian intellectuals and political leaders was able to identify proximity rather than distance, love of some kind rather than hatred, as the sources for amity as well as enmity among different Indian communities. The fundamental ambiguity implied by this idea made it impossible to adopt a wholly instrumental explanation of social relations in India, instead turning its terms into the elements of a new political thought.

Notes

- Of the many authors writing in this vein, Paul Brass is perhaps the most influential one today. See his The Production of Hindu-Muslim Violence in Contemporary India (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003). ↑

- See, for example, Bernard S. Cohn, Colonialism and its Forms of Knowledge: The British in India (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996). ↑

- See, for instance, the work of Arjun Appadurai, such as Fear of Small Numbers: An Essay on the Geography of Anger (Raleigh: Duke University Press, 2006), and Veena Das, Life and Words: Violence and the Descent into the Ordinary (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2006). ↑

- M.K. Gandhi, Hind Swaraj and Other Writings, ed. Anthony J. Parel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), p. 41. ↑

- Quoted in M.K. Gandhi, “Position of Women”, Young India, vol. XI no. 42, 17 October 1929, p. 4. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- B.R. Ambedkar, “What Congress and Gandhi have done to the Untouchables”, in Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings and Speeches, vol. 9 (Pune: Education Department, Government of Maharashtra, 1990), p. 291. ↑

- M.K. Gandhi, “Mr. Gandhi’s Letter”, Young India, 10 December 1919, p. 4. ↑

- Mohammad Iqbal, “Presidential address, delivered at the Annual Session of the All-India Muslim Conference at Lahore on the 21st March, 1932”, in Syed Abdul Vahid (ed.), Thoughts and Reflections of Iqbal (Lahore: Sh. Muhammad Ashraf, 1992), p. 211. ↑

- Ibid., p. 197. ↑

- Mohammad Iqbal, “Presidential Address Delivered at the Annual Session of the All-India Muslim League at Allahabad on the 29th December, 1930”, in Thoughts and Reflections of Iqbal, p. 162. ↑

- Mohammad Iqbal, “Qadianis and Orthodox Muslims”, in Thoughts and Reflections of Iqbal, pp. 248-9. ↑

Interests and Ideas

Whether by scholars, journalists, politicians or indeed participants in some riot, caste, religious, gender and other supposedly traditional forms of conflict in India tend to be seen in very similar ways. However simple or complex the explanation proffered, such conflict is understood as being made up of inherited prejudices and repackaged sentiments, both embedded within a changing structure of social or economic relations. True or false as these analyses may be, interesting is their ubiquitous character as a kind of common sense. Whatever their differences, after all, these accounts rarely integrate such conflict into any conceptual framework. At most it is attributed to everyday political instrumentality, with otherwise latent religious views being exploited for electoral or commercial purposes by unscrupulous officials, hand in hand with criminals and local youth organizations.1

Emerging in colonial times, such explanations are linked to what Bernard S. Cohn called an imperial sociology of knowledge, in which the social sciences as they came to be known were deployed to make sense of conflict, if only with a view to control it.2 As actual or would-be instruments of the British and later Indian government, these accounts were never meant to address religious and other conflict as anything other than a problem, and not by considering it in conceptual or normative terms as political thought. Ironically, it was the older language of orientalist scholarship in the 18th and early 19th centuries, as well as that of religious debate and missionary activity during this period, that stood alone in taking these enmities seriously, rather than seeing them merely as examples of social dysfunction or the epiphenomena of economic struggles, to say nothing about the ambitions of strongmen.

While there have been a few excellent studies, mostly anthropological, that exit a colonial sociology of knowledge in exploring the local languages and internal logics of apparently primordial conflict in India,3 I am interested in the making of a new political vocabulary to understand it. In particular, I shall be occupied with the way in which figures like M.K. Gandhi and Mohammad Iqbal sought to remake the political language of their country. They did so by radicalizing a classically imperialist argument, that Indian politics was marked not by its lack of independence so much as of ideas and principles, and it was this situation that made British rule possible as well as necessary. The apparently ceaseless and inevitable animosity between religious and other groups there was said to require the presence of a foreign power to keep the peace between them.

Although there were many ideas and principles that Indians supposedly lacked, among them individualism or the ability to separate political from religious life, it is the alleged absence of interest as a political category (but strangely not an economic one) that I am concerned with. On the one hand Indians were meant to be so consumed by a generally pecuniary form of self-interest that they were willing to stoop to the most brutal violence in order to achieve it, even if this meant putting the greater good of the country and so their own future at risk. But on the other, Indians seemed willing to sacrifice their interests and even lives in superstitious or fanatical actions that were as much religious as political. And if some of these actions could be attributed to ignorance and poverty, the participation in them of prosperous and educated Indians always rendered such distinctions ambiguous.

Interests come in different sizes and shapes, including various gradations of individual and collective identity, each of which may contradict the others. The problem supposedly posed by India’s simultaneously excessive and recessive interests had to do not with their plurality so much as irrationality, which is to say their counter-productive character. Given their great internal differences, for example, how might Hindus and Muslims constitute political interests, unless it was negatively or due to mutual and hereditary antipathies? Why were economic, regional or indeed truly national forms of collective life unable to compete with caste or religious ones? The answers to these questions also involved pointing to some absence, whether of education, administration or independence, and thus doing little more than doubling the colonial narrative of lack as a category constitutive of India’s political life.

Now the colonial state was not the only agency that promoted the idea that India’s politics was constituted by absence. Indians themselves did the same, trying to address this lack either by seeking to fill it with more “rational” class or national interests, or by claiming that such an absence was a positive one and marked India’s peculiar genius as opposed to that of Europe. Both of these approaches, of course, were apologetic ones, but they were also, as I have suggested, radicalized into a new kind of argument as part of a conversation between Indian thinkers and politicians from different parties and communities. We shall see that this conversation turned an old imperial argument into a new Indian one, not least because the colonial state was no longer part of it. Crucial, in other words, is that while learning from the West, this debate was not part of a dialogue with it.

While the English word interest was used by Indian political thinkers, it is also important to note that the term has no exact equivalent in Indian languages. The idea of self-interest, for instance, may be conveyed by the term swarth, more commonly selfishness, while that of advantage more generally might be called fayda or benefit. It is then the English original that allows one to make sense of such redefined Indian terms, whose multiplicity indicates another kind of absence or inability, perhaps even the refusal to constitute a complete or one-to-one translation of interest in its theoretical and political sense into Indian vernaculars. That this is not due to the ignorance of such an original is clear and calls for an explanation of the difference in linguistic usage. Provisionally it might be possible to suggest that this difference indicates the ambiguity with which the word continues to be invested.

Like his peers, Gandhi started with the premise that interests didn’t exist in India, or at least didn’t define social relations there. But unlike many of them, he typically reversed its political meaning. For instead of attributing India’s colonization to such a lack of national or even religious interest, the Mahatma argued that it was Indian self-interest that had in fact enabled British rule. In a chapter of his 1909 tract Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule, called “Why was India lost?” Gandhi blamed colonialism not on the force of arms but rather the mutual interests of the British and the Indians in commerce:

Some Englishmen state that they took, and they hold, India by the sword. Both these statements are wrong. The sword is entirely useless for holding India. […]. Then it follows that we keep the English in India for our base self-interest. We like their commerce, they please us by their subtle methods, and get what they want from us.4

For Gandhi, then, interest was primarily an economic rather than political category, and it therefore resulted not in resistance so much as an all too easy acquiescence to the lure of wealth and comfort. And this meant that if colonialism was to be defeated, interest had to be rejected for sacrifice and duty as their own reward. This was one aspect of his famous doctrine, taken from the Bhagavad-Gita, of desire-less action or forsaking ends for means. Gandhi imagined that since property was not the basis of Indian society, it was neither possible nor desirable to found Indian social relations on interest, and in fact argued that it was only the establishment of the colonial state as a neutral or third party between Indians that made some kind of interest possible, though in a very limited sense.

In other words, Indians were compelled to adopt the character of interest groups whenever they dealt with the colonial state, which, by constituting itself as a mediator between parties, sought to engineer and guarantee contractual relations among them. When speaking about the relations of Hindus and Muslims in particular, Gandhi often described this form of mediation, and its creation of contractual relations through the sole agency of the state, as a system of “divide and rule”. By this he didn’t necessarily mean that the British were deliberately fooling their naïve Indian subjects into quarreling with one another, but rather that the very structure of interest and contract was divisive by definition, because it set the state up as mediator and guarantor for interests that were not at all natural but decided by its workings.

In Hind Swaraj it was doctors and lawyers who exemplified the workings of the colonial state, and not only because their authority was accredited by this state. Doctors mediated between the patient and his own body, robbing him of any control over it by sedulously inducing a dependence on medication instead. In this way the swaraj or self-rule of the individual was destroyed even at the most intimate, corporeal level, and he became a mere cog in the system of imperialism, with its medical and pharmaceutical establishment itself supported by British capital and the greed for profits. As for lawyers, they separated both individuals and groups from each other by interposing the law as a mediator between Indians in such a way as to deprive them of any direct dealings with one another that might result in a friendly or at least mutually agreeable resolution of their disagreement. By delivering justice as a third party, the law instead made amicable resolution impossible, and indeed relied upon forced settlements that could only prolong and embitter the rivalry between individuals as much as communities.

Had the state managed to universalize interest and make of it the basis of all social relations, however, it might have served to pacify India if only in a thoroughly unjust and exploitative way. But the problem was that interest did not define most of the ways in which Indians dealt with each other, for the colonial state’s reach was not total and it could therefore only make interests of those who came before its institutions, the courts of law in particular. It was therefore the contradiction between the interests of colonial society on the one hand, and the religious and other ways in which Indians dealt with each other on the other, that made for conflict and violence. And if the reach of the state was limited, it was because interest and contract were ideas that required private property to constitute the basis of society, for it was this over which individuals and groups fought to define themselves as interests.

Gandhi thought that property could not constitute the basis of Indian society, and that interests could not therefore define its manifold relations. This was because most Indians had no property of any kind, something the Mahatma saw as both a curse and a blessing in disguise. After all the fact that property and so interests could not dominate Indian social relations meant that these latter, however oppressive they might otherwise be, could serve eventually to roll back and displace any political or economic order founded on property and its necessary inequalities. As was his wont, the Mahatma made the weakest and most vulnerable sections of Indian society into the vanguard of this non-violent revolution, a problematic instance of which can be seen in his correspondence with a female disciple, Raihana Tyabji, who had written him about the importance of securing women equal rights of inheritance:

Why should women have either to beg or to fight in order to win back their birthright? It is strange—and also tragically comic—to hear man born of woman talk loftily of ‘the weaker sex’ and nobly promising ‘to give’ us our due! What is this nonsense about ‘giving’? Where is the ‘nobility’ and ‘chivalry’ in restoring to people that which has been unlawfully wrested from them by those having brute power in their hands?5

Publishing her letter in the journal Young India on the 17th of October 1929, Gandhi responded to it by arguing that while he would never countenance unequal treatment of men and women under the law, Tyabji’s desire was nevertheless one that sought to expand the role of property in defining Indian social relations. Given the country’s poverty, however, the inclusion of women among property-owners could only be accomplished by further entrenching class differences in India:

But I am uncompromising in the matter of woman’s rights. In my opinion she should labour under no legal disability not suffered by man. […]. But to remove legal inequalities will be a mere palliative. The root of the evil lies much deeper than most people realize. […]. Man has always desired power. Ownership of property gives this power. Man hankers also after posthumous fame based on power. This cannot be had, if property is progressively cut up in pieces as it must be if all the posterity become equal co-sharers. Hence the descent of property for the most part on the eldest male issue. Most women are married. And they are co-sharers, in spite of the law being against them, in their husbands’ power and privileges. […]. Whilst therefore I would always advocate the repeal of all legal disqualifications, I should have the enlightened women of India to deal with the root cause. Woman is the embodiment of sacrifice and suffering, and her advent to public life should therefore result in purifying it, in restraining unbridled ambition and accumulation of property. Let them know that millions of men have no property to transmit to posterity. Let us learn from them that it is better for the few to have no ancestral property at all.6

Gandhi’s recommendation, that women emphasize their received and undoubtedly patriarchal role as embodiments of sacrifice to undo the dominance of property in social relations, was perhaps rather impractical, though of the same nature as the communist vision of the proletariat or the half-developed colonial world as, respectively, the vanguard and weakest link in the chain of capitalism. He gave the same advice to so-called “untouchables” as well, as recounted angrily by the low-caste leader Ambedkar.7

If all this tells us anything, it is that the Mahatma’s criticism of interest and its basis in property was a theoretical one, and not just directed at women or Dalits for prejudicial reasons. When he came to speak about religious conflict, Gandhi could draw upon a general theory in normative political terms. His ambition was to develop the disinterest or idealism embedded even in the most hierarchical and oppressive social relations to refashion them in a radical direction. His great experiment to do so was made during the Khilafat Movement in the immediate aftermath of the First World War, when Indian Muslims began to protest British and French moves to dismember the defeated Ottoman Empire.

Having contributed the bulk of India’s troops to the war, especially in the Middle East, and having been promised by the British prime minister that Muslim shrines and sanctities would not be interfered with, many Indian Muslims sought to have their sentiments respected as loyal subjects of the Empire. And it was to Gandhi that they turned for leadership in a movement that went on to become the first mass mobilisation in Indian history. Apart from seeing the justice of their claims and counselling a non-violent approach to the colonial state, the Mahatma was fascinated by the Khilafat Movement precisely because it was so difficult to construe it as an interest of any kind. Dedicated to the preservation of a foreign power, in whose support India’s Muslims expended great efforts and sent large amounts of money, the movement seemed to be a truly religious and therefore idealistic or disinterested one.

Because it was idealistic, or even fanatical and irrational, and not launched for an ulterior and therefore interested motive, as the British but also Hindu nationalists imagined, Gandhi thought the Khilafat could transform Indian politics more generally. Now there were many Hindus and Muslims, too, who sought to establish the movement on a contract and so interest, whereby the former’s support would be predicated upon the latter’s abandonment of cow-slaughter. But Gandhi steadfastly rejected such calls and wanted to base Hindu-Muslim unity upon the relations of love and sacrifice that he thought marked friendship or brotherhood as potentially if not always actually disinterested relations. This, rather than interest and contract, would secure India’s unity and freedom:

The test of friendship is assistance in adversity, and that too, unconditional assistance. Co-operation that needs consideration is a commercial contract and not friendship. Conditional co-operation is like adulterated cement which does not bind. It is the duty of the Hindus, if they see the justice of the Mahomedan cause, to render co-operation. If the Mahomedans feel themselves bound in honour to spare the Hindus’ feelings and to stop cow-killing, they may do so, no matter whether the Hindus co-operate with them or no. Though, therefore, I yield to no Hindu in my worship of the cow, I do not want to make the stopping of cow-killing a condition precedent to co-operation. Unconditional co-operation means the protection of the cow.8

Like Gandhi, Mohammad Iqbal, the pre-eminent Muslim poet and thinker of the 20th century, didn’t think a society based on interest was either possible or desirable in India. Thus in his presidential address of 1932 to the All-India Muslim Conference, Iqbal argued that the kind of democracy promoted by Indian nationalists was premised upon what he called the “money-economy of modern democracy”. Such a democratic order, in other words, rested upon the assumption that citizens were constituted of individual and self-owning voters for whom interests, too, were understood as properties to be defended. But this form of polity, Iqbal thought, was absolutely foreign to India’s peasant majority:

The present struggle in India is sometimes described as India’s revolt against the West. I do not think it is a revolt against the West; for the people of India are demanding the very institutions which the West stands for. Whether the gamble of elections, retinues of party leaders and hollow pageants of parliaments will suit a country of peasants for whom the money-economy of modern democracy is absolutely incomprehensible, is a different question altogether. Educated urban India demands democracy. The minorities, feeling themselves as distinct cultural units and fearing that their very existence is at stake, demand safeguards, which the majority community, for obvious reasons, refuses to concede. The majority community pretends to believe in a nationalism theoretically correct, if we start from Western premises, belied by facts, if we look to India. Thus the real parties to the present struggle in India are not England and India, but the majority community and the minorities of India which can ill-afford to accept the principle of Western democracy until it is properly modified to suit the actual conditions of life in India.9

Iqbal thought that Congress nationalism, with its focus on electorally-defined interests, had either naively or deliberately misread the nature of Indian society by describing it in supposedly univeral but in fact specifically European terms. And the repercussions of this misunderstanding, he imagined, were likely to be disastrous. Iqbal joined Gandhi in advocating not the creation of interests where they didn’t exist, but instead working to limit them. For he thought that India’s various groups and communities were defined not by property so much as ideals or principles, upon which structures of power, too, were built. However violent such ideals might occasionally be, Iqbal recognized them as extraordinary in their potential to make history out of spirit and principle, which is to say by the transcendental however defined.

While he thought that property had not yet come to define Indian social relations, then, Iqbal saw in nationalism private property writ large as communal ownership, and understood the nation-state as constituing its epitome as much as guarantor. By excluding the transcendent or ideal element of India’s existing social relations, and confining them in good liberal fashion to private life, the form of citizenship characteristic of nationalism ended up making public life entirely materialistic and violent in its instrumentality. The nation-state, in other words, professed to include and tolerate religious and other communities based on ideals, but in fact served to destroy or at least hollow them out. And communism, which Iqbal saw as Islam’s only rival as a global alternative to the existential violence of capitalism, he thought simply magnified the role of property in public life by giving it into the possession of the state. In a Marxist state, then, citizens were even more enslaved to property than in a capitalist one.

Iqbal’s task, then, was to retrieve the ideal or spiritual element in India’s social relations. But instead of doing so in Gandhi’s way, by magnifying everyday forms of disinterest or sacrifice into world-historical events, Iqbal remained true to his profession as a poet and philosopher by choosing a more intellectual path. In addition to protecting the apparently irrational aspects of inherited religious practice so as to forestall the domination of property and interest, as we have seen the Mahatma did by his encouragement of caste and gender-defined propertylessness, Iqbal strove to elaborate poetically upon the unpropertied social relations that he thought defined India. These he described as representing “invisible points of contact” between Hindus and Muslims in particular. Such relations were invisible not simply because they were increasingly hidden in the shadow of interests, but also due to the fact that visibility immediately rendered these communities into forms of ownership in which Muslims had to protect mosques from Hindu music while the latter protected cows from Muslim slaughter:

In view of the visible and invisible points of contact between the various communities of India I do believe in the possibility of constructing a harmonious whole whose unity cannot be disturbed by the rich diversity which it must carry within its bosom. The problem of ancient Indian thought was how the one became many without sacrificing its oneness. To-day this problem has come down from its ethical heights to the grosser plane of our political life, and we have to solve it in its reversed form, i.e., how the many can become one without sacrificing its plural character.10

Plurality was important for Iqbal not simply because he was concerned with the fate of minorities in India, but because ideals were necessarily and substantively different. In other words this was quite unlike a world defined by property, ownership and interest, which reduced multiplicity to a merely symbolic status in which, from the point of view of the nation-state as a third party, each difference had the same weight as and was substitutible with another. It was only by seeing Hindus and Muslims, or upper and lower castes, as mutually substitutible pairs, after all, however distinctive and unequal they might otherwise be, that they could become competitors as interest groups. Every piece of property, too, however distinctive, was comparable and so substitutible with any other, for they were equalized by being valued in monetary terms through contracts guaranteed by the state as itself a reified form of property. And it was this false intimacy of competition and substitution that Iqbal rejected by focussing on the real and unconvertible differences of all that was ideal, spiritual or principled.

Precisely because Muslims in India were a diverse and scattered minority, thought Iqbal, they were defined by ideals more than their co-religionists anywhere else in the world. As he put it in an address to the Muslim League in 1930:

It cannot be denied that Islam, regarded as an ethical ideal plus a certain kind of polity—by which expression I mean a social structure regulated by a legal system and animated by a specific ethical ideal—has been the chief formative factor in the life history of the Muslims of India. It has furnished those basic emotions and loyalties which gradually unify scattered individuals and groups and finally transform them into a well-defined people. Indeed it is no exaggeration to say that India is perhaps the only country in the world where Islam as a society is almost entirely due to the working of Islam as a culture inspired by a specific ethical ideal.11

And it was this spiritual sense of community that made Islam so vulnerable to nationalism as much as what he called religious adventurism in a 1934 article on the Ahmadi sect:

Islam repudiates the race idea altogether and founds itself on the religious idea alone. Since Islam bases itself on the religious idea alone, a basis which is wholly spiritual and consequently far more ethereal than blood relationship, Muslim society is naturally much more sensitive to forces which it considers harmful to its integrity.12

A letter in Urdu by Gandhi lamenting Muhammad Iqbal’s death and recalling the powerful impact of his memorable poem, 9 June 1938.

By deferring and delaying the advent of the nation-state, in recommending, for instance, India’s internal re-distribution into Hindu and Muslim dominated provinces, Iqbal tried to preserve not just the ideal foundation of Islam, but also the invisible points of contact that made up Indian social relations as a whole. And while his political solutions were of a rather negative kind, Iqbal also rehearsed these invisible relations in his poetry and philosophy, where Hindus and Muslims came to stand for metaphysical rather than sociological categories, being removed from the instrumentality of politics and so rendered unfit to become equivalents of one another.

A new political language or way of thinking emerged during the two or three decades leading up to India’s independence in 1947. While it started out by making use of colonial themes and categories, this form of thought quickly radicalised them into something quite novel. The received notion that Indian society was constituted by a series of lacks or absences, for example, and therefore subject to colonisation, was taken up if only to be turned into an idea beyond European recognition. The interests that Indians were supposed to possess either in excess or insufficiently came to provide political thinkers there with ways of reimagining their future. Gandhi and Iqbal tried to limit if not roll them back, attributing India’s religious and caste conflict precisely to the increasing dominance of property and so interests in public life.

Important about this debate was the fact that it managed to exit the largely instrumental and administrative categories of a colonial sociology of knowledge, locating as it did religious, caste and other ostensibly traditional relations within the normative arena of what I am calling political thought. And by taking leave of a narrative in which such relations could only figure as problems to be resolved, this conversation between Indian intellectuals and political leaders was able to identify proximity rather than distance, love of some kind rather than hatred, as the sources for amity as well as enmity among different Indian communities. The fundamental ambiguity implied by this idea made it impossible to adopt a wholly instrumental explanation of social relations in India, instead turning its terms into the elements of a new political thought.

Notes

- Of the many authors writing in this vein, Paul Brass is perhaps the most influential one today. See his The Production of Hindu-Muslim Violence in Contemporary India (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003). ↑

- See, for example, Bernard S. Cohn, Colonialism and its Forms of Knowledge: The British in India (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996). ↑

- See, for instance, the work of Arjun Appadurai, such as Fear of Small Numbers: An Essay on the Geography of Anger (Raleigh: Duke University Press, 2006), and Veena Das, Life and Words: Violence and the Descent into the Ordinary (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2006). ↑

- M.K. Gandhi, Hind Swaraj and Other Writings, ed. Anthony J. Parel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), p. 41. ↑

- Quoted in M.K. Gandhi, “Position of Women”, Young India, vol. XI no. 42, 17 October 1929, p. 4. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- B.R. Ambedkar, “What Congress and Gandhi have done to the Untouchables”, in Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings and Speeches, vol. 9 (Pune: Education Department, Government of Maharashtra, 1990), p. 291. ↑

- M.K. Gandhi, “Mr. Gandhi’s Letter”, Young India, 10 December 1919, p. 4. ↑

- Mohammad Iqbal, “Presidential address, delivered at the Annual Session of the All-India Muslim Conference at Lahore on the 21st March, 1932”, in Syed Abdul Vahid (ed.), Thoughts and Reflections of Iqbal (Lahore: Sh. Muhammad Ashraf, 1992), p. 211. ↑

- Ibid., p. 197. ↑

- Mohammad Iqbal, “Presidential Address Delivered at the Annual Session of the All-India Muslim League at Allahabad on the 29th December, 1930”, in Thoughts and Reflections of Iqbal, p. 162. ↑

- Mohammad Iqbal, “Qadianis and Orthodox Muslims”, in Thoughts and Reflections of Iqbal, pp. 248-9. ↑