PDF

Download

Citations

Click and drag then release to select a passage to cite.

Annotations

How to submit annotations to Mizan Journal articles:

your work is published.

Search within

Quentin Skinner beh Fārsī

A Contextualist Reckoning with Islamic Protestantism

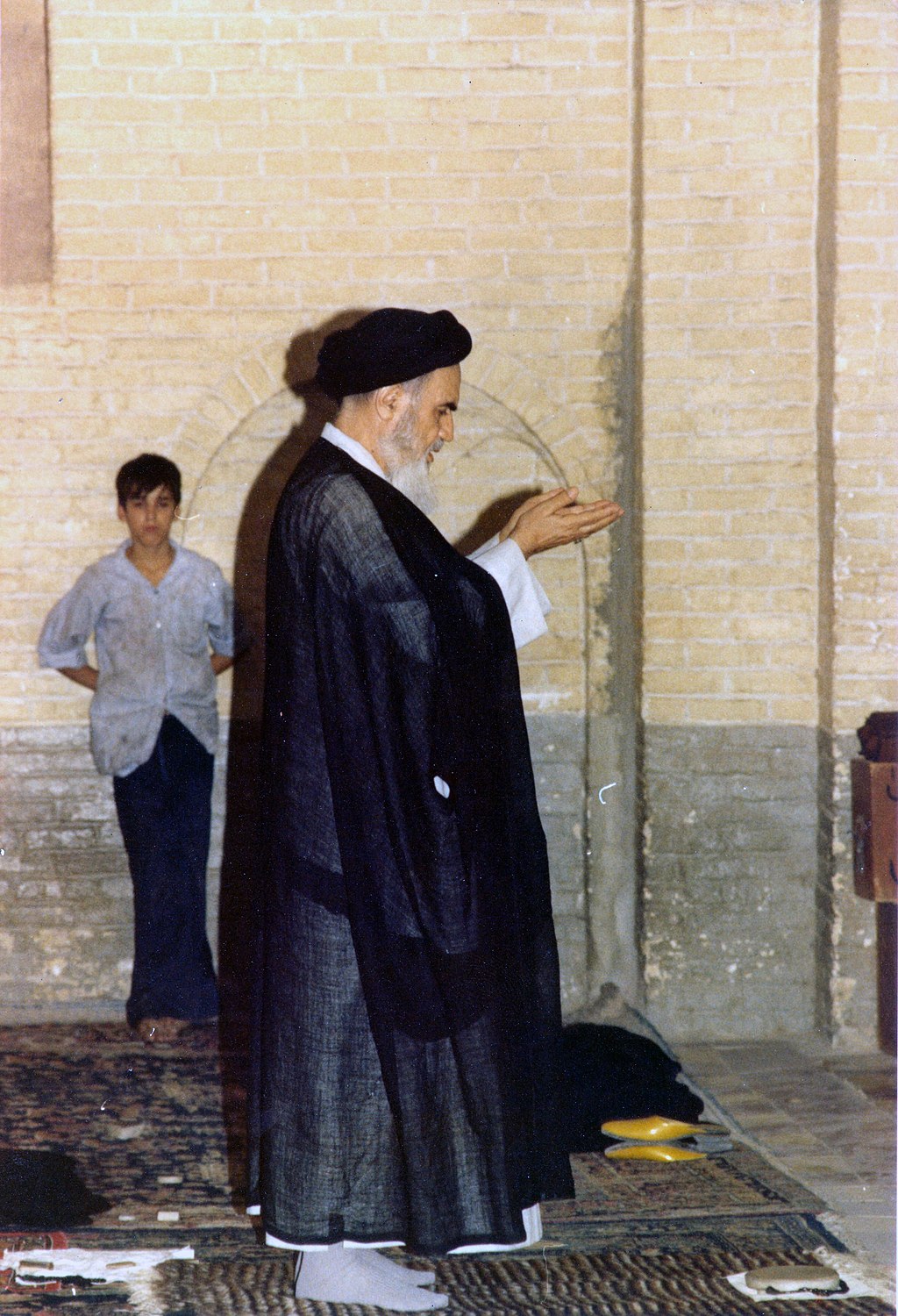

Image

Audio

Video

Chart or Graph

Quentin Skinner beh Fārsī

A Contextualist Reckoning with Islamic Protestantism

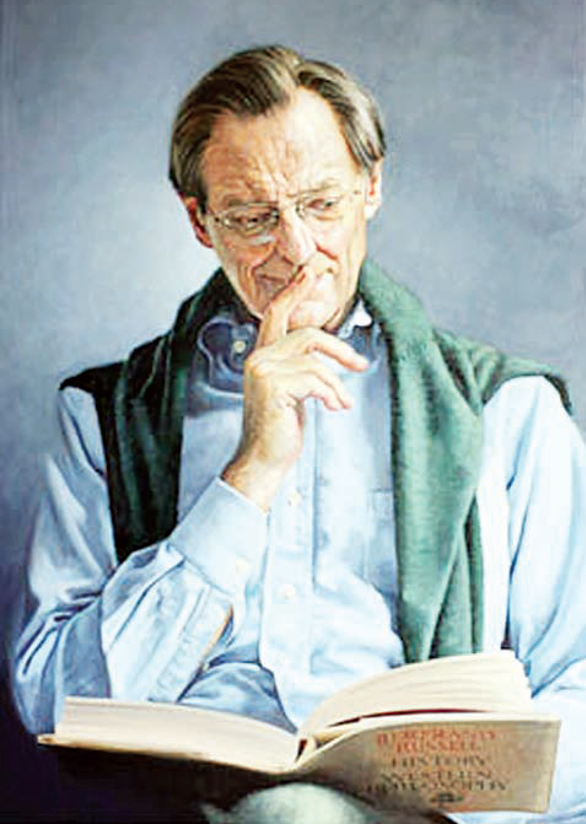

1 In 2014 the left-leaning Iranian cultural monthly, Mehrnameh, published a series of articles on Quentin Skinner. Supplemented by a translated interview with the historian,2 the three articles focus on Skinner’s methodological contributions to the study of political thought, namely contextualisation and authorial intention, that have helped generate what has come to be known as the Cambridge School of intellectual history. Each article interprets Skinner’s work to provide a new perspective on, or critique of, Iran’s revolutionary and post-revolutionary intellectual topography. And for each contributor, Skinner’s method offers in some way a broader understanding and assessment of Iranian history and, therefore, of Iranian national identity. The first article promotes Skinner’s approach as an alternative to the dominant methods of pure textualism, contextualism, and essentialism. For Matin Ghaffariyan, “idol-smashing modern historical myths” is the priority.3 The third article examines Skinner’s influences and appraises his idea of “text as political action.”4 While these two articles mostly avoid an examination of Iranian political theology and thus of Islam, the second article places it front and centre.

This essay will discuss the second article of the series entitled “Summoning Skinner to the Iranian Battlefield.”5The author engages in a reception history of Skinner’s work to correct misinterpretations of the revolutionary-socialist-cum-Islamist intellectual, ‘Ali Shari‘ati (d. 1977). Mohammad-Javad Gholam-Reza Kashi—a supporter of the now-banned Islamic Iran Participation Front, a reformist party established in 1998 and led by Mohammad-Reza Khatami6—traces misinterpretations of Shari‘ati to post-revolutionary debates and ideas. For Kashi, the post-revolutionary era experienced the rise of intellectual trends used to define and re-define the legacy of Iranian intellectuals throughout the nation’s history. It is against these trends that Kashi wields Skinner as a weapon against Shari‘ati’s intellectual legacy. Yet, argues Kashi, Shari‘ati’s defenders and detractors alike are ignorant of how present politics fashions their perspectives. Where Morteza Motahhari (d. 1979)—Khomeini’s (d. 1989) erstwhile student and revolutionary philosopher—once viewed Shari‘ati as an enemy of clerical authority, Shari‘ati is now praised by many as a leading revolutionary.

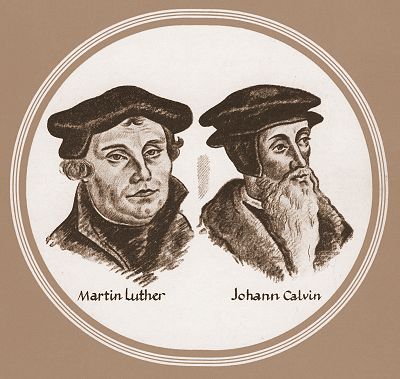

But Kashi takes issue with interpretations neither of Shari‘ati’s Marxism nor his Islamism. Instead, Kashi’s problem is with how Shari‘ati’s idea of Protestantism is not but should be distinguished from that of Luther and Calvin. The primary target of his critique therefore focuses on an earlier article about Shari‘ati and religious reform. Mohammad Quchani’s article entitled “The Tragedy of Islamic Protestantism: How Does Religious Reform Lead to Religious Tyranny?” was also published in Mehrnameh and resulted in a temporary halt of publications by the Ministry of Guidance. Quchani argued in his article that Muslim-reformist intellectuals from Shari‘ati to the Green Movement’s Mir-Husayn Musavi (former prime minister in house arrest since 2009) promoted a brand of Protestantism comparable though not identical to that of Luther and Calvin. The similarities between the two pairs lie in their opposition to traditional structures of religious authority, promotion of spiritual liberty, and theological reform. Their differences, on the other hand, according Quchani are found in their effects: Shari‘ati’s Protestantism led to “religious despotism” (istibdad-e dini) and the latter led to liberalism. But Kashi implores a contextualisation of Christian (read: “Western”) Protestantism and Shari‘ati’s Protestantism alike, arguing that the two should be understood as completely separate political developments with consideration of context and authorial intention. In other words, to summon Skinner to the battlefield is to reject a search for origins as well as an author’s perennial effect.

What, however, is the broader significance of Kashi’s article? First, Kashi’s article represents a reckoning with Iranian history by engaging with current Euro-American-based debates on method. He uses Skinner to reform and update his peers’ understanding of the recent past, targeting a controversial Mehrnameh article on Shari‘ati’s Protestantism. Perhaps in doing so Kashi unintentionally entered the battlefield against which he wrote and to which he summoned Skinner. Nevertheless, his effort entails not only an engagement with the Islamic Republic’s past and present but also implicitly asks what role revolution—whether “Glorious” in England or “Islamic” in Iran—might play in shaping past and present intellectual histories. He consequently promotes a historical method for which a revolution’s effects in general and current Iranian politics in particular might challenge the universality of value-laden concepts that are most often defined as “Western”—that is, those concepts rooted in liberalism, which, in a master narrative proceeded from the Glorious Revolution of 1688.7 But Kashi further implies, as we will see, that neither Christian nor Islamic Protestantism can claim ownership of pluralism and democracy, on one hand, and of religious despotism on the other. For we should remember that violence, not liberalism, ensued not only after the Iranian Revolution, but also after the Protestant Reformation; violence in the post-revolutionary experience is less a product of the content of revolutionary ideologies than of the nature of post-revolutionary social orders.

Second, and following from the first, Kashi departs from Skinner by addressing religion.8 Although Kashi does not explicitly state as his intention to depart from Skinner’s secular method, the former’s argument nevertheless serves as a critique not only of his Iranian peers but also as a meta-critique of Skinner’s context-centric, and thus comparative-resistant method. This is why Kashi’s engagement with a Euro-American-centric debate on method is important. Kashi does not appropriate Skinner to critique religion. Indeed, he does not attempt to explain any kind of political theology at all. Instead, he appropriates methods of intellectual history formed outside of Iran as a way to embed his argument about Iran and Islam in global discussions on “who gets to write history?” and “who gets to debate method?” His engagement in these debates, despite critiquing his peers, serves as an Iranian claim to authority for writing intellectual history outside of parochial circles.9 But, like a good Skinnerian, a contextual synopsis of Kashi’s article is in order before arguing these two points.

Contextualising the Debate

According to Kashi, the post-revolutionary period experienced a rush of opinions on the legacies of Iranian intellectuals. This is partially an effect of the “Cultural Revolution” (1981-83), which purged universities and other public institutions of ideological undesirables. The result was that a number of purged educators found a new source of income in translation, initiating a flood of previously inaccessible thought now published in Persian by Iranians.10 However, the growing “marketplace of ideas,” Kashi argues, brought with it the present urgency for a “comprehension of comprehending” and a “critique of critique;” a re-evaluation, if you will, of certain ideas is now necessary. He therefore asserts that elucidating Iran’s intellectual history in the present is an existential duty, which will also help to determine post-revolutionary Iranian identity.

Kashi tackles his re-evaluation and assessment first with a description of what he defines as the three dominant trends for critique and comprehension in contemporary Iran. He then continues with a Skinnerian refutation of these trends to propose a fourth, alternative method. The three dominant trends for comprehension and critique accordingly are ideological, rational, and pragmatic. The ideological trend, he says, is a relic of the pre-revolutionary period. It is one in which all are beholden to obligations and prohibitions in order to support the ethics of the political majority. Concepts and terms are used to support a norm or ideal while the lexicon with which one critiques or comprehends intellectual value is determined by the author’s affiliation. The result is an appraisal of all thought as either traitorous or revolutionary. The rational trend, present from the late 1960s, limits critique to “outside realities” and objective criteria. In other words, the extent to which an intellectual’s inquiry is compatible with that of others determines the veracity of his/her argument. When engaging in this approach, one should ask the following: “to what extent is there consensus with other intellectuals of the particular period?” This, Kashi explains, resulted in a kind of “house-cleaning” by which some intellectuals (none of whom are named) were replaced with more palatable ones to create uniformity. The final trend is the pragmatic one. Kashi summons concrete historical examples to critique this trend, which he argues is the “most up-to-date” method of critique and comprehension and enjoys a warm reception among current intellectuals. It allows for an assessment of ideas based on their consequences and effects. Intellectuals from the Constitutional Revolution (1906-1911), Kashi argues, have been appraised in this way. For example, if ideas appear consistent with and supportive of democracy and freedom, but are then “negated” or are proven to be antithetical, then they are unacceptable. This trend, he says, has accordingly been used to silence intellectual independence or to separate moderate ideas from radical ideologies.

But Kashi is not entirely opposed to the third trend. He argues that “Iranian pragmatism” has some parallels both with Skinner’s method, which “is also pragmatist,” and with the ideological trend. In all three, speech is considered a social, cultural, and political action. But where the ideological trend attempts to maintain certain principles, the pragmatic trend supposedly relinquishes a preference for social or political principles. Skinner’s approach, Kashi asserts, can help demonstrate the importance of pre-revolutionary Muslim intellectuals while Iranian pragmatism—as he describes—has been conflicted because Iranian pragmatists do not give Muslim intellectuals a meaningful role.

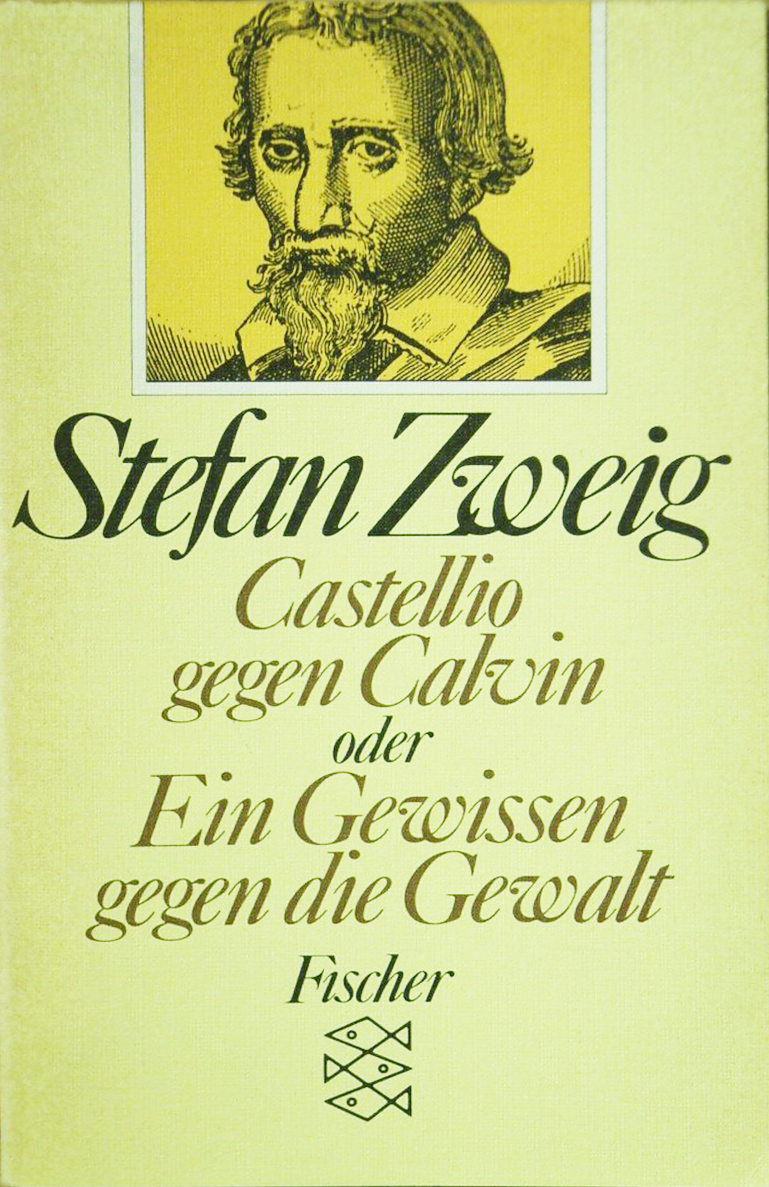

Kashi’s critique then turns to Mohammad Quchani, who by implication is an Iranian pragmatist. To answer the question of “how religious reform leads to tyranny,” Quchani begins by painting a bleak picture of the reformist politician and ostracised presidential candidate, Mir-Husayn Musavi, described by Quchani in his article’s introduction as reading The Right to Heresy: Castellio against Calvin (1936) by Stefan Zweig.

Musavi, an intellectual “son of Shari‘ati” as described by Quchani, frequently attended the late revolutionary’s lectures at the Husayniyya Irshad—the same institution where Motahhari had lectured as Shari‘ati’s rival. Quchani argues that Shari‘ati identified a model in medieval-Christian Protestantism through which religious freedom, that is, a more communitarian religious conscience, might overcome clerical authority and result in political liberty.11 Protestantism in Shari‘ati’s “Weberian” worldview, on the other hand, promotes a brand of ethics that fosters a spirit of Capitalism by which countries with higher Protestant populations are more economically advanced than those without.12 But Quchani’s argument is not without context and consequence.

Quchani narrates a history of Luther and Calvin, along with an overview of Protestantism in Muslim and Christian thought.

These parallel narratives seem to help explain how the noble intentions of Luther and Calvin, on the one hand, and Shari‘ati on the other, resulted in disparate and unequal conditions. But because Protestantism in Islam is completely based on European values and histories, his comparative narrative relies on an essential difference between Luther and Calvin’s organic Protestantism versus Protestantism’s attraction for (rather than development in) Islam: Christian Protestantism has a non-linear, contingent history, while Islamic Protestantism is composed of a grab-bag of values that emerged long after the Glorious Revolution. He also identifies some Muslim parallels to Protestantism (such as Isma‘ilis and Druze, he says), as well as their appeal in Iran among intellectuals like, for example, the secular-reformist Mirza Fath-Ali Akhundzadeh (d. 1878).

On revolution, says Quchani, Luther opposed action because of his extreme conservative reformism—he was purely concerned with theological ethics and the Church; Calvin later implemented Luther’s ideas in a revolutionary program, a relationship that is analogous for Quchani to Marx’s relationship with Lenin13 (i.e., Luther and Marx : Calvin and Lenin :: he who theorises : he who implements theory). In other words, while Luther was unconcerned with establishing a new state and only with the ethical relationship between Church, state, and believer, placing anti-clericalism as religious liberty at its core, Calvin wanted to change the relationship between divine and earthly law—and thus the nature of state and sovereign.

When contrasted with Islam, Quchani explains, any religious reform would be dependent on state and therefore politics because Islam had never been separated from government (as, he says, Caesar had been separated from God).14For example, Quchani contends, religious reform in Sunnism, namely Salafism, was influenced to a degree by Marxism. (Yet, absent in Quchani’s discussion is “On the Jewish Question” in which Marx advocated political liberation with the state’s abandonment of an official religion.) But neither the Salafis—among whom Quchani includes Shari‘ati—nor other reformers and modernists have succeeded in true liberation. In fact, he argues, the opposite seems to have occurred. It is due to Christian and Islamic Protestantism’s respective outcomes that Quchani eventually concludes the following:

Maybe after a hundred years of looking for the Iranian, Shi‘i, or Muslim Luther and Calvin, we should look for the Erasmus. Perhaps Iranian society needs John Locke more than it needs Martin Luther; and [perhaps it] needs more political reform than religious reform because I saw religious reform ending with religious tyranny.15

Kashi argues against the kind of value judgements undertaken by Quchani, asserting that Shari‘ati’s defenders and detractors engage in methodological errors, which Skinner can help to remedy. Kashi defines Skinner’s method as composed of two perspectives for a single subject. The first is the subject’s (i.e., the author’s) social and political surroundings—like the backstory of a play. This first perspective allows one to understand the supporting events and catalysts that fashion the second perspective. The second perspective is the subject’s intention, which depends on the first perspective when effecting change. But they cannot be separated lest this result in an erroneous understanding of history. According to Kashi, Shari‘ati’s defenders accuse his critics of ignoring both perspectives and ignorance of his reformist intentions. As a result, they completely misjudge his character. But Shari‘ati’s defenders, like Quchani, attribute to his thought ahistorical values and therefore overlook conceptual change over time; that is, they ignore the variegated contexts and connotations of “liberty, democracy, justice, and religious reform.” Their mistake is to promote a myth of paradigm and coherence when, in reality, no such exists. Kashi qualifies that neither Christian nor Islamic Protestantism originally entailed a paradigmatic defense of pluralism and democracy. Nor, he says, did they defend or directly lead to religious despotism. He promotes a contextual basis from which to launch his attack against “essentialists” who attempt to “transform thinkers into historical saviours or criminals.”16

In his conclusion, Kashi applies his critique to contemporary Iranian politics. He accuses those like Quchani of interpreting history for political motives; these motives at the time of Quchani’s article were part of a larger effort to influence the 2014 parliamentary elections. Placing Shari‘ati alongside Da‘esh (The Islamic State in Iraq and Syria) demonstrates the possibility for alternative and contingent politics. With such a juxtaposition, however, different visions of Islam and ghosts of intellectuals past might emerge in the service of “temporary political camps.” But these camps interpret all intellectuals from the Constitutional Revolution to the present with a revolutionary litmus test. Kashi therefore implores the following: instead of interpreting intellectuals from the Constitutional Revolution to the present through a revolutionary/post-revolutionary lens, and instead of summoning those very intellectuals to serve present political interests, Skinner should be summoned to offer a new kind of pragmatism in order to contextualise the different periods in which these intellectuals functioned.17

A Revolutionary Reckoning

To be sure, Kashi’s re-assessment of the pre-revolutionary past is hardly apolitical. But his debate is not one in which one side defends and the other attacks Shari‘ati. It is instead part of a wider debate on authority over pre/post-revolutionary values, history, and national identity. In other words, to what extent does the Iranian Revolution, or the experience of revolution in general, influence ideas of rupture and continuity in intellectual history?

In his seminal work, The Whig Interpretation of History (1931), the early twentieth-century historian Herbert Butterfield critiqued the master narrative, that the fruits of modern liberalism can be traced through the smooth historical continuity from the Glorious Revolution to the present. The narrative in which modern liberal values and ideals evolved steadily from the Protestant Reformation to the late-medieval period, to the emergence of early-modern Protestant ethics is dishonest or accidental at best and insidious at worst. For Butterfield, this narrative is a pillar of Euro-American identity mostly unquestioned by historians but requiring an intervention.

More recently, however, James Simpson has argued that liberal values often associated with the Glorious Revolution are due to historical rupture rather than an accident. Simpson agrees that values found in modern Euro-American history are a product of Protestantism but he shows that instead of continuity or accidental “liberalization,” these values were possible only because of existential necessity. In order to stop the violence of the late-medieval period, not between Catholics and Protestants but among Protestants, liberalism formed as a repudiation of the past—as an ideological break with Protestantism itself. He therefore proposes a diachronic methodology for studying revolution (all revolutions) in order to map ideological and conceptual change.18

Every successful revolution entails historical rupture. And, as David Armitage has argued, every great revolution is a civil war.19 At the same time, as Herbert Butterfield’s Whig Interpretation implies, intellectuals seek continuity for political purposes. But these political purposes need not be insidious. Most people seek and value national or cultural identity, which is undeniably tied to a simplified historical narrative. But once a master narrative emerges, it then becomes exceedingly difficult to question the values that the narrative promotes. In the case of Protestantism, these values remain under the umbrella of liberalism: pluralism, reason, and religious freedom. Without a semblance of historical continuity, however, national and cultural identity is precarious and too easily contested.

For Quchani, historical continuity is found in the admirable though unsuccessful effort by Iranian-Muslim intellectuals to effect religious liberation from the shackles of tradition. His argument appears in many ways as an effort to discredit the 1979 Revolution as one that placed clerical authority as the highest form of state authority. The historiographical implication of his article is a reinterpretation of pre-revolutionary intellectuals to excavate kernels of anti-revolutionary and more “liberal” thought; it is an endeavour to search for alternatives to clerical authority and to enact religious reform.

But Quchani falls into the same trap as Butterfield and that which Simpson targets and Kashi, for other reasons, opposes. Quchani, in seeking to liberate himself from the master narrative of revolution, also promotes continuity dictated by the very terms of the Iranian Revolution. In other words, he remains tied to the same structures of authority against which he attempts to speak. On the one hand, his argument depends on a Euro-American constellation of values on which some Iranian intellectuals drew to apply in a “Muslim” context. On the other hand, he calls on the very intellectuals who are now—like Shari‘ati—mobilised to serve the Islamic Republic.

Alternatively, Kashi attempts for “Islamic” Protestantism what Butterfield and Simpson attempted for Reformation-era Protestantism. But in attempting to deracinate intellectual history from the lens of revolutionary ideology, Kashi engages in two polemics. First, his promotion of Skinner’s contextualism and authorial intention challenges the very values that are so often attributed to a Euro-American political and cultural history—Kashi well understands that Luther and Calvin never promoted such modern-liberal values that are promoted today. Second, as Simpson attempted for the Reformation, Kashi advocates a reckoning with the Iranian Revolution’s role as a watershed for conceptual change; he also proposes a diachronic method to understand these changes.

With Skinner’s method, Kashi argues that modern-European liberalism was not, in fact, what Luther and Calvin promoted, just as liberal pluralism and Muslim spiritual liberty were not really what Shari‘ati promoted. This allows for certain values as concepts to be historicised in their entirety. Those kernels of Protestant liberalism that Shari‘ati supposedly promoted become prominent in current opposition politics—for some Iranian reformists—just as liberty, religious freedom, and justice become conceptually significant in modern Euro-American liberalism when looking back on late-medieval Protestantism.

As Kashi explains, “thinking about the structures of the evolution of ideas in everyday life and language… Skinner advises us to focus our attention on what meaning Islam bore in the revolutionary practice of ‘57 (1979) and what transformation this meaning underwent in the following period…”20 In Skinner’s words, we must try to “see things their way.”21 Kashi, like Skinner, defines concepts as completely contingent on social/political context and agency (though Skinner gives explicit primacy to the author’s agency over context).22 The meaning of Shari‘ati’s Protestantism should therefore—according to Kashi’s Skinnerian view—be separated completely from that of Luther and Calvin. But Skinner qualifies that transformations over time are less defined by changes in conceptual meaning than by changes in how terms are applied to express certain concepts.23 Terminology, in other words is a reflection of social currents in which values ebb and flow.

For Skinner, lexical choice is political. Normative concepts, he argues, such as liberty, democracy, justice, and pluralism function more as weapons of ideological debate than they do as statements about the world.24 “No one is above the battle” of politics and morality, notes Skinner, even if they attempt a dispassionate analysis.25

Skinner also emphasises the importance of asking why a concept came to prominence or experienced a resurgence at a particular moment.26 Why and against what, in other words, might an author deploy such a concept? But in summoning Skinner, Kashi implores only historiographical reform without engaging in a serious consideration of why—beyond immediate electoral or post-revolutionary politics—Protestantism versus, say, another strand of religious reform gained prominence in twentieth-century Iran. Indeed, such debates are coloured by the dominant historiography of European democracy, which, so the narrative says, blossomed from the Protestant Reformation and supposedly provides the reason for Iran and the Islamic world’s failure to produce analogous political thought or praxis.

An in-depth answer for why Islamic Protestantism gained currency is outside the scope of this article. But surely the Protestantism that emerged “after the Revolution with Soroush”27 is, unlike its Christian namesake, fashioned by a preceding revolution in which a different kind of political theology triumphed against that of Soroush and Shari‘ati. Khomeini’s successful revolution, in its establishment of earthly institutions and constitutionalism, along with an emphasis on public “spirituality,” appears to have rendered Islamic Protestantism, whether as reform or revolution, irrelevant as a force for meaningful change; Khomeini’s politics triumphed over that of Shari‘ati and Soroush.

With a dispassionate reception of intellectual history—but not actual authorship of any history—against such a controversial article, Kashi seems to have wandered into the very battlefield to which he summoned Skinner, even if unwittingly. Despite Kashi’s self-proclaimed dispassion, he and his target are both reformists. Yet Kashi pulls no punches toward the end of his article in accusing his political target(s) of weaponising intellectuals, without any acknowledgement that he might also be weaponising concepts. (It is also worth noting that this debate is occurring, as Kashi notes, three decades after the Iranian Revolution; Simpson and Butterfield’s debate is centuries after their revolution.) Kashi oscillates between viewing Quchani as a political thinker—critiquing him as someone with political motives—and as a historian with a faulty methodology.

Nevertheless, Quchani experienced the political consequences of his article from the Ministry of Guidance while there was an ostensible lack of public interest in Kashi’s article. To an extent, this difference indicates the spectrum of politics of intellectual history in the Islamic Republic. That Kashi’s call for an intervention in the historiography of past Iranian thought is less controversial than a push for continuity, albeit against a master narrative, might indicate the following: that maintaining the continuity of an official narrative is more important than preventing calls for historical rupture, especially if this rupture is not explicitly opposed to the Islamic Republic’s revolutionary ideology.

Writing Intellectual History as Sovereignty

At the heart of Kashi’s battlefield is sovereignty. Kashi and Quchani alike are concerned with how religious thought might be historicised as a political force through which revolution or reform are enacted. Both ask how pluralism, liberty, and democracy—as they relate to political theology—might possess an autonomous history in the Islamic world. In other words, can a history of these values be written without tracing their genealogies to the West and thus establishing dependence?

If Muslim efforts to promote such values have resulted in religious tyranny, as they do according to Quchani, then, for a Skinnerian, it is less because of erroneous thought or practice than it is context and immediate ideological necessity. Skinnerian logic is as follows: Salafists, among whom Shari‘ati is sometimes included,28 who promote pluralism of religious interpretation only employ violent action or militant rhetoric because of their intention vis-à-vis their social opposition (i.e., against clerics or agnostic intellectuals) or political foes (i.e., the state). For a Skinnerian, the Furqan group as self-professed followers of Shari‘ati used violence not because of a violent essence found in Shari‘ati’s thought but because of their immediate context and ideology—both of which must be understood in a separate context from that which is labelled “liberal.”

Is it possible to write a non-Western intellectual history of so-called liberal values? Does Shari‘ati’s thought—and other intellectuals about whom Quchani writes—represent the espousal of liberal values which then underwent illiberal manifestations? If these questions are to be answered, then religion as a whole would have to be reconsidered and twinned with politics. Shari‘ati—and all Muslim theorists of revolution and reform for that matter—might conceivably dislodge master narratives that place the works of Luther and Calvin, and later Enlightenment thinkers, as canon. For canon is defined as such only because of its perceived role in effecting change or its salience in subsequent politics. An attempt at a modern intellectual history of Iran would redefine political texts not only in relation to kingship, on the one hand, and a religious establishment on the other, but also against historiography that sees certain values as paradigmatically Western or liberal and exogenous to Islam and “the East.” Without giving undue credit to Kashi, it is important to note that he does not intend on such a debate. Instead he makes the debate on modern Iranian intellectual history public and urgent. His discussion on values in the context of two “Protestantisms” and his refusal to separate history into that of religious and secular ideas is significant even if he does not acknowledge so.

To be sure, Skinner’s disinterest in the history of religious thought, of which Kashi appears unaware, has been a point of contention among intellectual historians.29 Skinner is, in his own terms, “self-conscious” of his “insensitivity” to religion. But this self-consciousness is not a product of any self-admitted methodological flaw in his work. His self-consciousness is instead a product of what he terms the “re-sacrilizing of the world.” Skinner sees this re-sacrilising as the reversal of Weberian and Marxist secular modernity which makes him uncomfortable. While his earlier work, Foundations of Modern Political Thought (1978), focused heavily on the relationship between religious principles and political change, Skinner says that his subsequent works are fashioned by his “boring atheism” from which his utter lack of attention to religious history stems.30

Is this supposed re-sacrilising a reversal of secularism—a phrase which should arouse suspicion—or is it the reorientation of religious and secular politics? Kashi demonstrates Skinner’s inability to answer or address this question. Skinner’s blind spot is indeed best remedied by the success of the Iranian Revolution, which laid the foundations for the production of modern Iranian intellectual history. The revolutionary lens with which Kashi is concerned is crucial for a diachronic intellectual history, which acknowledges and embraces a historical rupture while attempting to “see things their way,” that is, the author’s way, as a means for mapping conceptual change. Such scholarship of the modern period, however, must also engage with domestic political debates.

Engaging with contemporary domestic political debates is not an argument for nativism. Instead, it encourages the use of sources in which current debates on politics and conceptual change occur, as in the pages of Mehrnameh and other public forums. These forums demonstrate the very historical reckoning with which the present essay is concerned. And such a reckoning, not among European or American historians but among Iranians, in which religion plays a crucial political role—a role for material and social change over a theological one—demonstrates that the Iranian Revolution succeeded not only in establishing a new state but also a new ideational context for studying the history of political thought. The Revolution, in other words, reoriented the content and structure of global political authority in which concepts that were previously thought to have a secular history might as well possess a history without strict secular and religious divisions, let alone Western ownership.

Conclusion

The triumph of Khomeini’s revolutionary ideology over “Islamic Protestantism” or liberal iterations of Islam undoubtedly challenges the latter’s ability to effect great political change. Is not liberal freedom what all the world desires? Or perhaps, then, Khomeini “hijacked” the revolution and pushed it toward an alternative form of despotism? That such a revolution produced a challenge to dominant ways of writing history—or at least a condition in which Iranians are writing their own history in conversation with Western historians—should make anyone apprehensive of these questions. Despite deploying Skinner, whose method eschews religion’s importance, Kashi offers the potential to redefine sovereignty against theories that place religious authority in the annals of pre-Enlightenment thought. And despite his reception of a European intellectual historian, Kashi offers a critique only of Iranian authors without a critique of Skinner.

Unbeknownst to Skinner and his cohort, and regardless of Kashi’s intention, this dialogue nevertheless illustrates an emerging equilibrium in what is still often seen as a lopsided world—secular in the West contra religious in the East. In other words, Kashi’s reception reads contemporary intellectual history in the West (in all its parochialism) as a global discussion in which Iranians within Iran must participate. Although Skinner argues against the existence of perennial questions and strict contextualism, implicitly disallowing for a comparison between religious thought across time and space, Kashi’s insistence on Islam (even in its various forms)—as an autonomous force for change and the power to assert its own values—ironically allows for bolder scholarship than either Skinner or Kashi explicitly endorse. That the potential for such scholarship and dialogue, whatever its potential manifestations, comes from a post-revolutionary-“Islamic” Iran is a reckoning in itself.

Notes

- I would like to thank the editor of this issue, Neguin Yavari, as well as the ILEX Foundation for sponsoring this project and its publication. ↑

- For the original interview see Danny Millum, “Quentin Skinner,” in Making History: the changing face of the profession in Britain (18 April 2008). URL: https://www.history.ac.uk/makinghistory/resources/interviews/Skinner_Quentin.html. ↑

- Matīn Ghaffāriyān, “Butshikana usṭūra-hā-yi mudurn-i tārīkhī: darbāra-yi Ku’intīn Iskīnir bā bahāna-yi intishār-i kitāb bīnash-hā-yi ‘ilm-i siyāsat,” Mihrnāma 37 (2014): 268, at 268. ↑

- Mūsā Akramī, “Matn-i siyāsī dar maqām-i kunish-i siyāsī: Ku’intīn Iskīnir: nigāhī bih mabānī-i ravishshinākhtī va dastāvard-hā,” Mihrnāma 37(2014): 271-274. ↑

- Muḥammad-Javād Ghulām-Riżā Kāshī, “Farākhān-i Iskīnir bih maydān-i munāzi‘a Īrānī,” Mihrnāma 37 (2014): 269-270. ↑

- Ali Gheissari and Kaveh Cyrus-Sanandaji, “New Conservative Politics and Electoral Behavior in Iran,” in Contemporary Iran: Economy, Society, Politics, ed., Ali Gheissari (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 275-298, at 280. ↑

- See, for example, James Simpson, Permanent Revolution: The Reformation and the Illiberal Roots of Liberalism (Boston: Harvard University Press, 2019). ↑

- See the following interview with Skinner: Teresa Bejan, “Quentin Skinner: The Art of Theory Interview (2011),” The Art of Theory (2011). URL: https://www.uncanonical.net/skinner. ↑

- For an acknowledgment of the harms of intellectual history’s parochialism, see John Dunn, “Why We Need a Global History of Political Thought,” In Zusammenarbeit mit dem Husserl-Archiv Freiburg und dem Lehrstuhlfür Politische Philosophie, Theorie und Ideengeschichte, 21/11/2013. URL: http://www.husserlarchiv.de/materialien/JohnDunnConf/JohnDunnConf4. ↑

- Esmaeil Haddadian-Moghaddam, Literary Translation in Modern Iran: A Sociological Study (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2014), 118-19. ↑

- Muḥammad Qūchānī, “Trājidī-yi Prūtistāntīsm-i Islāmī: chigūna az iṣlāḥ-i dīnī, istibdād-i dīnī sar bar mī āvarad,” Mihrnāma, no. 36 (2014): 22-33, at 22. ↑

- Ibid., 22. ↑

- Ibid., 23. ↑

- Ibid., 24; Here Quchani quotes the dissident Taqi Rahmani. Ibid., 33. ↑

- Ibid., 33. ↑

- Kāshī, “Farākhān-i Iskīnir,” 270. ↑

- Ibid., 270. ↑

- Simpson, Permanent Revolution, 2-6. ↑

- David Armitage, “Every Great Revolution Is a Civil War,” in Scripting Revolution: A Historical Approach to the Comparative Study of Revolutions, edited by Keith Michael Baker and Dan Edelstein (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2015), 57-68 and 269-71. ↑

- Kāshī, “Farākhān-i Iskīnir,” 270. ↑

- Quentin Skinner, Visions of Politics: Volume 1: Regarding Method (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 1. ↑

- Ibid., 176; Ibid., 7. ↑

- Ibid., 179. ↑

- Ibid., 177. ↑

- Ibid., 7. ↑

- Ibid., 178. ↑

- Kāshī, “Farākhān-i Iskīnir,” 270. ↑

- Quchani recognises the existence of Shi‘i Salafists while Reinhard Schulze has labeled Shari‘ati the only Shi‘i Salafi. Qūchānī, Trādzidī-i Prūtistāntīsm-i Islāmī,” 33; Reinhard Schulze, A Modern History of the Islamic World, tr., Azizeh Azodi (New York and London: I.B. Tauris, 2002), 176-177. ↑

- See John Coffey, “Quentin Skinner and the Religious Dimension of Early Modern Political Thought,” in Seeing Things Their Way: Intellectual History and the Return of Religion, eds., Alister Chapman, John Coffey, and Brad S. Gregory (University of Notre Dame Press, 2009), 46-74; Neguin Yavari, Advice for the Sultan: Prophetic Voices and Secular Politics in Medieval Islam (London: Hurst, 2014), 143-155. Also see Yavari, Advice for the Sultan, on writing a history of non-Western political thought. ↑

- Bejan, “Quentin Skinner.” ↑

Quentin Skinner beh Fārsī

A Contextualist Reckoning with Islamic Protestantism

1 In 2014 the left-leaning Iranian cultural monthly, Mehrnameh, published a series of articles on Quentin Skinner. Supplemented by a translated interview with the historian,2 the three articles focus on Skinner’s methodological contributions to the study of political thought, namely contextualisation and authorial intention, that have helped generate what has come to be known as the Cambridge School of intellectual history. Each article interprets Skinner’s work to provide a new perspective on, or critique of, Iran’s revolutionary and post-revolutionary intellectual topography. And for each contributor, Skinner’s method offers in some way a broader understanding and assessment of Iranian history and, therefore, of Iranian national identity. The first article promotes Skinner’s approach as an alternative to the dominant methods of pure textualism, contextualism, and essentialism. For Matin Ghaffariyan, “idol-smashing modern historical myths” is the priority.3 The third article examines Skinner’s influences and appraises his idea of “text as political action.”4 While these two articles mostly avoid an examination of Iranian political theology and thus of Islam, the second article places it front and centre.

This essay will discuss the second article of the series entitled “Summoning Skinner to the Iranian Battlefield.”5The author engages in a reception history of Skinner’s work to correct misinterpretations of the revolutionary-socialist-cum-Islamist intellectual, ‘Ali Shari‘ati (d. 1977). Mohammad-Javad Gholam-Reza Kashi—a supporter of the now-banned Islamic Iran Participation Front, a reformist party established in 1998 and led by Mohammad-Reza Khatami6—traces misinterpretations of Shari‘ati to post-revolutionary debates and ideas. For Kashi, the post-revolutionary era experienced the rise of intellectual trends used to define and re-define the legacy of Iranian intellectuals throughout the nation’s history. It is against these trends that Kashi wields Skinner as a weapon against Shari‘ati’s intellectual legacy. Yet, argues Kashi, Shari‘ati’s defenders and detractors alike are ignorant of how present politics fashions their perspectives. Where Morteza Motahhari (d. 1979)—Khomeini’s (d. 1989) erstwhile student and revolutionary philosopher—once viewed Shari‘ati as an enemy of clerical authority, Shari‘ati is now praised by many as a leading revolutionary.

But Kashi takes issue with interpretations neither of Shari‘ati’s Marxism nor his Islamism. Instead, Kashi’s problem is with how Shari‘ati’s idea of Protestantism is not but should be distinguished from that of Luther and Calvin. The primary target of his critique therefore focuses on an earlier article about Shari‘ati and religious reform. Mohammad Quchani’s article entitled “The Tragedy of Islamic Protestantism: How Does Religious Reform Lead to Religious Tyranny?” was also published in Mehrnameh and resulted in a temporary halt of publications by the Ministry of Guidance. Quchani argued in his article that Muslim-reformist intellectuals from Shari‘ati to the Green Movement’s Mir-Husayn Musavi (former prime minister in house arrest since 2009) promoted a brand of Protestantism comparable though not identical to that of Luther and Calvin. The similarities between the two pairs lie in their opposition to traditional structures of religious authority, promotion of spiritual liberty, and theological reform. Their differences, on the other hand, according Quchani are found in their effects: Shari‘ati’s Protestantism led to “religious despotism” (istibdad-e dini) and the latter led to liberalism. But Kashi implores a contextualisation of Christian (read: “Western”) Protestantism and Shari‘ati’s Protestantism alike, arguing that the two should be understood as completely separate political developments with consideration of context and authorial intention. In other words, to summon Skinner to the battlefield is to reject a search for origins as well as an author’s perennial effect.

What, however, is the broader significance of Kashi’s article? First, Kashi’s article represents a reckoning with Iranian history by engaging with current Euro-American-based debates on method. He uses Skinner to reform and update his peers’ understanding of the recent past, targeting a controversial Mehrnameh article on Shari‘ati’s Protestantism. Perhaps in doing so Kashi unintentionally entered the battlefield against which he wrote and to which he summoned Skinner. Nevertheless, his effort entails not only an engagement with the Islamic Republic’s past and present but also implicitly asks what role revolution—whether “Glorious” in England or “Islamic” in Iran—might play in shaping past and present intellectual histories. He consequently promotes a historical method for which a revolution’s effects in general and current Iranian politics in particular might challenge the universality of value-laden concepts that are most often defined as “Western”—that is, those concepts rooted in liberalism, which, in a master narrative proceeded from the Glorious Revolution of 1688.7 But Kashi further implies, as we will see, that neither Christian nor Islamic Protestantism can claim ownership of pluralism and democracy, on one hand, and of religious despotism on the other. For we should remember that violence, not liberalism, ensued not only after the Iranian Revolution, but also after the Protestant Reformation; violence in the post-revolutionary experience is less a product of the content of revolutionary ideologies than of the nature of post-revolutionary social orders.

Second, and following from the first, Kashi departs from Skinner by addressing religion.8 Although Kashi does not explicitly state as his intention to depart from Skinner’s secular method, the former’s argument nevertheless serves as a critique not only of his Iranian peers but also as a meta-critique of Skinner’s context-centric, and thus comparative-resistant method. This is why Kashi’s engagement with a Euro-American-centric debate on method is important. Kashi does not appropriate Skinner to critique religion. Indeed, he does not attempt to explain any kind of political theology at all. Instead, he appropriates methods of intellectual history formed outside of Iran as a way to embed his argument about Iran and Islam in global discussions on “who gets to write history?” and “who gets to debate method?” His engagement in these debates, despite critiquing his peers, serves as an Iranian claim to authority for writing intellectual history outside of parochial circles.9 But, like a good Skinnerian, a contextual synopsis of Kashi’s article is in order before arguing these two points.

Contextualising the Debate

According to Kashi, the post-revolutionary period experienced a rush of opinions on the legacies of Iranian intellectuals. This is partially an effect of the “Cultural Revolution” (1981-83), which purged universities and other public institutions of ideological undesirables. The result was that a number of purged educators found a new source of income in translation, initiating a flood of previously inaccessible thought now published in Persian by Iranians.10 However, the growing “marketplace of ideas,” Kashi argues, brought with it the present urgency for a “comprehension of comprehending” and a “critique of critique;” a re-evaluation, if you will, of certain ideas is now necessary. He therefore asserts that elucidating Iran’s intellectual history in the present is an existential duty, which will also help to determine post-revolutionary Iranian identity.

Kashi tackles his re-evaluation and assessment first with a description of what he defines as the three dominant trends for critique and comprehension in contemporary Iran. He then continues with a Skinnerian refutation of these trends to propose a fourth, alternative method. The three dominant trends for comprehension and critique accordingly are ideological, rational, and pragmatic. The ideological trend, he says, is a relic of the pre-revolutionary period. It is one in which all are beholden to obligations and prohibitions in order to support the ethics of the political majority. Concepts and terms are used to support a norm or ideal while the lexicon with which one critiques or comprehends intellectual value is determined by the author’s affiliation. The result is an appraisal of all thought as either traitorous or revolutionary. The rational trend, present from the late 1960s, limits critique to “outside realities” and objective criteria. In other words, the extent to which an intellectual’s inquiry is compatible with that of others determines the veracity of his/her argument. When engaging in this approach, one should ask the following: “to what extent is there consensus with other intellectuals of the particular period?” This, Kashi explains, resulted in a kind of “house-cleaning” by which some intellectuals (none of whom are named) were replaced with more palatable ones to create uniformity. The final trend is the pragmatic one. Kashi summons concrete historical examples to critique this trend, which he argues is the “most up-to-date” method of critique and comprehension and enjoys a warm reception among current intellectuals. It allows for an assessment of ideas based on their consequences and effects. Intellectuals from the Constitutional Revolution (1906-1911), Kashi argues, have been appraised in this way. For example, if ideas appear consistent with and supportive of democracy and freedom, but are then “negated” or are proven to be antithetical, then they are unacceptable. This trend, he says, has accordingly been used to silence intellectual independence or to separate moderate ideas from radical ideologies.

But Kashi is not entirely opposed to the third trend. He argues that “Iranian pragmatism” has some parallels both with Skinner’s method, which “is also pragmatist,” and with the ideological trend. In all three, speech is considered a social, cultural, and political action. But where the ideological trend attempts to maintain certain principles, the pragmatic trend supposedly relinquishes a preference for social or political principles. Skinner’s approach, Kashi asserts, can help demonstrate the importance of pre-revolutionary Muslim intellectuals while Iranian pragmatism—as he describes—has been conflicted because Iranian pragmatists do not give Muslim intellectuals a meaningful role.

Kashi’s critique then turns to Mohammad Quchani, who by implication is an Iranian pragmatist. To answer the question of “how religious reform leads to tyranny,” Quchani begins by painting a bleak picture of the reformist politician and ostracised presidential candidate, Mir-Husayn Musavi, described by Quchani in his article’s introduction as reading The Right to Heresy: Castellio against Calvin (1936) by Stefan Zweig.

Musavi, an intellectual “son of Shari‘ati” as described by Quchani, frequently attended the late revolutionary’s lectures at the Husayniyya Irshad—the same institution where Motahhari had lectured as Shari‘ati’s rival. Quchani argues that Shari‘ati identified a model in medieval-Christian Protestantism through which religious freedom, that is, a more communitarian religious conscience, might overcome clerical authority and result in political liberty.11 Protestantism in Shari‘ati’s “Weberian” worldview, on the other hand, promotes a brand of ethics that fosters a spirit of Capitalism by which countries with higher Protestant populations are more economically advanced than those without.12 But Quchani’s argument is not without context and consequence.

Quchani narrates a history of Luther and Calvin, along with an overview of Protestantism in Muslim and Christian thought.

These parallel narratives seem to help explain how the noble intentions of Luther and Calvin, on the one hand, and Shari‘ati on the other, resulted in disparate and unequal conditions. But because Protestantism in Islam is completely based on European values and histories, his comparative narrative relies on an essential difference between Luther and Calvin’s organic Protestantism versus Protestantism’s attraction for (rather than development in) Islam: Christian Protestantism has a non-linear, contingent history, while Islamic Protestantism is composed of a grab-bag of values that emerged long after the Glorious Revolution. He also identifies some Muslim parallels to Protestantism (such as Isma‘ilis and Druze, he says), as well as their appeal in Iran among intellectuals like, for example, the secular-reformist Mirza Fath-Ali Akhundzadeh (d. 1878).

On revolution, says Quchani, Luther opposed action because of his extreme conservative reformism—he was purely concerned with theological ethics and the Church; Calvin later implemented Luther’s ideas in a revolutionary program, a relationship that is analogous for Quchani to Marx’s relationship with Lenin13 (i.e., Luther and Marx : Calvin and Lenin :: he who theorises : he who implements theory). In other words, while Luther was unconcerned with establishing a new state and only with the ethical relationship between Church, state, and believer, placing anti-clericalism as religious liberty at its core, Calvin wanted to change the relationship between divine and earthly law—and thus the nature of state and sovereign.

When contrasted with Islam, Quchani explains, any religious reform would be dependent on state and therefore politics because Islam had never been separated from government (as, he says, Caesar had been separated from God).14For example, Quchani contends, religious reform in Sunnism, namely Salafism, was influenced to a degree by Marxism. (Yet, absent in Quchani’s discussion is “On the Jewish Question” in which Marx advocated political liberation with the state’s abandonment of an official religion.) But neither the Salafis—among whom Quchani includes Shari‘ati—nor other reformers and modernists have succeeded in true liberation. In fact, he argues, the opposite seems to have occurred. It is due to Christian and Islamic Protestantism’s respective outcomes that Quchani eventually concludes the following:

Maybe after a hundred years of looking for the Iranian, Shi‘i, or Muslim Luther and Calvin, we should look for the Erasmus. Perhaps Iranian society needs John Locke more than it needs Martin Luther; and [perhaps it] needs more political reform than religious reform because I saw religious reform ending with religious tyranny.15

Kashi argues against the kind of value judgements undertaken by Quchani, asserting that Shari‘ati’s defenders and detractors engage in methodological errors, which Skinner can help to remedy. Kashi defines Skinner’s method as composed of two perspectives for a single subject. The first is the subject’s (i.e., the author’s) social and political surroundings—like the backstory of a play. This first perspective allows one to understand the supporting events and catalysts that fashion the second perspective. The second perspective is the subject’s intention, which depends on the first perspective when effecting change. But they cannot be separated lest this result in an erroneous understanding of history. According to Kashi, Shari‘ati’s defenders accuse his critics of ignoring both perspectives and ignorance of his reformist intentions. As a result, they completely misjudge his character. But Shari‘ati’s defenders, like Quchani, attribute to his thought ahistorical values and therefore overlook conceptual change over time; that is, they ignore the variegated contexts and connotations of “liberty, democracy, justice, and religious reform.” Their mistake is to promote a myth of paradigm and coherence when, in reality, no such exists. Kashi qualifies that neither Christian nor Islamic Protestantism originally entailed a paradigmatic defense of pluralism and democracy. Nor, he says, did they defend or directly lead to religious despotism. He promotes a contextual basis from which to launch his attack against “essentialists” who attempt to “transform thinkers into historical saviours or criminals.”16

In his conclusion, Kashi applies his critique to contemporary Iranian politics. He accuses those like Quchani of interpreting history for political motives; these motives at the time of Quchani’s article were part of a larger effort to influence the 2014 parliamentary elections. Placing Shari‘ati alongside Da‘esh (The Islamic State in Iraq and Syria) demonstrates the possibility for alternative and contingent politics. With such a juxtaposition, however, different visions of Islam and ghosts of intellectuals past might emerge in the service of “temporary political camps.” But these camps interpret all intellectuals from the Constitutional Revolution to the present with a revolutionary litmus test. Kashi therefore implores the following: instead of interpreting intellectuals from the Constitutional Revolution to the present through a revolutionary/post-revolutionary lens, and instead of summoning those very intellectuals to serve present political interests, Skinner should be summoned to offer a new kind of pragmatism in order to contextualise the different periods in which these intellectuals functioned.17

A Revolutionary Reckoning

To be sure, Kashi’s re-assessment of the pre-revolutionary past is hardly apolitical. But his debate is not one in which one side defends and the other attacks Shari‘ati. It is instead part of a wider debate on authority over pre/post-revolutionary values, history, and national identity. In other words, to what extent does the Iranian Revolution, or the experience of revolution in general, influence ideas of rupture and continuity in intellectual history?

In his seminal work, The Whig Interpretation of History (1931), the early twentieth-century historian Herbert Butterfield critiqued the master narrative, that the fruits of modern liberalism can be traced through the smooth historical continuity from the Glorious Revolution to the present. The narrative in which modern liberal values and ideals evolved steadily from the Protestant Reformation to the late-medieval period, to the emergence of early-modern Protestant ethics is dishonest or accidental at best and insidious at worst. For Butterfield, this narrative is a pillar of Euro-American identity mostly unquestioned by historians but requiring an intervention.

More recently, however, James Simpson has argued that liberal values often associated with the Glorious Revolution are due to historical rupture rather than an accident. Simpson agrees that values found in modern Euro-American history are a product of Protestantism but he shows that instead of continuity or accidental “liberalization,” these values were possible only because of existential necessity. In order to stop the violence of the late-medieval period, not between Catholics and Protestants but among Protestants, liberalism formed as a repudiation of the past—as an ideological break with Protestantism itself. He therefore proposes a diachronic methodology for studying revolution (all revolutions) in order to map ideological and conceptual change.18

Every successful revolution entails historical rupture. And, as David Armitage has argued, every great revolution is a civil war.19 At the same time, as Herbert Butterfield’s Whig Interpretation implies, intellectuals seek continuity for political purposes. But these political purposes need not be insidious. Most people seek and value national or cultural identity, which is undeniably tied to a simplified historical narrative. But once a master narrative emerges, it then becomes exceedingly difficult to question the values that the narrative promotes. In the case of Protestantism, these values remain under the umbrella of liberalism: pluralism, reason, and religious freedom. Without a semblance of historical continuity, however, national and cultural identity is precarious and too easily contested.

For Quchani, historical continuity is found in the admirable though unsuccessful effort by Iranian-Muslim intellectuals to effect religious liberation from the shackles of tradition. His argument appears in many ways as an effort to discredit the 1979 Revolution as one that placed clerical authority as the highest form of state authority. The historiographical implication of his article is a reinterpretation of pre-revolutionary intellectuals to excavate kernels of anti-revolutionary and more “liberal” thought; it is an endeavour to search for alternatives to clerical authority and to enact religious reform.

But Quchani falls into the same trap as Butterfield and that which Simpson targets and Kashi, for other reasons, opposes. Quchani, in seeking to liberate himself from the master narrative of revolution, also promotes continuity dictated by the very terms of the Iranian Revolution. In other words, he remains tied to the same structures of authority against which he attempts to speak. On the one hand, his argument depends on a Euro-American constellation of values on which some Iranian intellectuals drew to apply in a “Muslim” context. On the other hand, he calls on the very intellectuals who are now—like Shari‘ati—mobilised to serve the Islamic Republic.

Alternatively, Kashi attempts for “Islamic” Protestantism what Butterfield and Simpson attempted for Reformation-era Protestantism. But in attempting to deracinate intellectual history from the lens of revolutionary ideology, Kashi engages in two polemics. First, his promotion of Skinner’s contextualism and authorial intention challenges the very values that are so often attributed to a Euro-American political and cultural history—Kashi well understands that Luther and Calvin never promoted such modern-liberal values that are promoted today. Second, as Simpson attempted for the Reformation, Kashi advocates a reckoning with the Iranian Revolution’s role as a watershed for conceptual change; he also proposes a diachronic method to understand these changes.

With Skinner’s method, Kashi argues that modern-European liberalism was not, in fact, what Luther and Calvin promoted, just as liberal pluralism and Muslim spiritual liberty were not really what Shari‘ati promoted. This allows for certain values as concepts to be historicised in their entirety. Those kernels of Protestant liberalism that Shari‘ati supposedly promoted become prominent in current opposition politics—for some Iranian reformists—just as liberty, religious freedom, and justice become conceptually significant in modern Euro-American liberalism when looking back on late-medieval Protestantism.

As Kashi explains, “thinking about the structures of the evolution of ideas in everyday life and language… Skinner advises us to focus our attention on what meaning Islam bore in the revolutionary practice of ‘57 (1979) and what transformation this meaning underwent in the following period…”20 In Skinner’s words, we must try to “see things their way.”21 Kashi, like Skinner, defines concepts as completely contingent on social/political context and agency (though Skinner gives explicit primacy to the author’s agency over context).22 The meaning of Shari‘ati’s Protestantism should therefore—according to Kashi’s Skinnerian view—be separated completely from that of Luther and Calvin. But Skinner qualifies that transformations over time are less defined by changes in conceptual meaning than by changes in how terms are applied to express certain concepts.23 Terminology, in other words is a reflection of social currents in which values ebb and flow.

For Skinner, lexical choice is political. Normative concepts, he argues, such as liberty, democracy, justice, and pluralism function more as weapons of ideological debate than they do as statements about the world.24 “No one is above the battle” of politics and morality, notes Skinner, even if they attempt a dispassionate analysis.25

Skinner also emphasises the importance of asking why a concept came to prominence or experienced a resurgence at a particular moment.26 Why and against what, in other words, might an author deploy such a concept? But in summoning Skinner, Kashi implores only historiographical reform without engaging in a serious consideration of why—beyond immediate electoral or post-revolutionary politics—Protestantism versus, say, another strand of religious reform gained prominence in twentieth-century Iran. Indeed, such debates are coloured by the dominant historiography of European democracy, which, so the narrative says, blossomed from the Protestant Reformation and supposedly provides the reason for Iran and the Islamic world’s failure to produce analogous political thought or praxis.

An in-depth answer for why Islamic Protestantism gained currency is outside the scope of this article. But surely the Protestantism that emerged “after the Revolution with Soroush”27 is, unlike its Christian namesake, fashioned by a preceding revolution in which a different kind of political theology triumphed against that of Soroush and Shari‘ati. Khomeini’s successful revolution, in its establishment of earthly institutions and constitutionalism, along with an emphasis on public “spirituality,” appears to have rendered Islamic Protestantism, whether as reform or revolution, irrelevant as a force for meaningful change; Khomeini’s politics triumphed over that of Shari‘ati and Soroush.

With a dispassionate reception of intellectual history—but not actual authorship of any history—against such a controversial article, Kashi seems to have wandered into the very battlefield to which he summoned Skinner, even if unwittingly. Despite Kashi’s self-proclaimed dispassion, he and his target are both reformists. Yet Kashi pulls no punches toward the end of his article in accusing his political target(s) of weaponising intellectuals, without any acknowledgement that he might also be weaponising concepts. (It is also worth noting that this debate is occurring, as Kashi notes, three decades after the Iranian Revolution; Simpson and Butterfield’s debate is centuries after their revolution.) Kashi oscillates between viewing Quchani as a political thinker—critiquing him as someone with political motives—and as a historian with a faulty methodology.

Nevertheless, Quchani experienced the political consequences of his article from the Ministry of Guidance while there was an ostensible lack of public interest in Kashi’s article. To an extent, this difference indicates the spectrum of politics of intellectual history in the Islamic Republic. That Kashi’s call for an intervention in the historiography of past Iranian thought is less controversial than a push for continuity, albeit against a master narrative, might indicate the following: that maintaining the continuity of an official narrative is more important than preventing calls for historical rupture, especially if this rupture is not explicitly opposed to the Islamic Republic’s revolutionary ideology.

Writing Intellectual History as Sovereignty

At the heart of Kashi’s battlefield is sovereignty. Kashi and Quchani alike are concerned with how religious thought might be historicised as a political force through which revolution or reform are enacted. Both ask how pluralism, liberty, and democracy—as they relate to political theology—might possess an autonomous history in the Islamic world. In other words, can a history of these values be written without tracing their genealogies to the West and thus establishing dependence?

If Muslim efforts to promote such values have resulted in religious tyranny, as they do according to Quchani, then, for a Skinnerian, it is less because of erroneous thought or practice than it is context and immediate ideological necessity. Skinnerian logic is as follows: Salafists, among whom Shari‘ati is sometimes included,28 who promote pluralism of religious interpretation only employ violent action or militant rhetoric because of their intention vis-à-vis their social opposition (i.e., against clerics or agnostic intellectuals) or political foes (i.e., the state). For a Skinnerian, the Furqan group as self-professed followers of Shari‘ati used violence not because of a violent essence found in Shari‘ati’s thought but because of their immediate context and ideology—both of which must be understood in a separate context from that which is labelled “liberal.”

Is it possible to write a non-Western intellectual history of so-called liberal values? Does Shari‘ati’s thought—and other intellectuals about whom Quchani writes—represent the espousal of liberal values which then underwent illiberal manifestations? If these questions are to be answered, then religion as a whole would have to be reconsidered and twinned with politics. Shari‘ati—and all Muslim theorists of revolution and reform for that matter—might conceivably dislodge master narratives that place the works of Luther and Calvin, and later Enlightenment thinkers, as canon. For canon is defined as such only because of its perceived role in effecting change or its salience in subsequent politics. An attempt at a modern intellectual history of Iran would redefine political texts not only in relation to kingship, on the one hand, and a religious establishment on the other, but also against historiography that sees certain values as paradigmatically Western or liberal and exogenous to Islam and “the East.” Without giving undue credit to Kashi, it is important to note that he does not intend on such a debate. Instead he makes the debate on modern Iranian intellectual history public and urgent. His discussion on values in the context of two “Protestantisms” and his refusal to separate history into that of religious and secular ideas is significant even if he does not acknowledge so.

To be sure, Skinner’s disinterest in the history of religious thought, of which Kashi appears unaware, has been a point of contention among intellectual historians.29 Skinner is, in his own terms, “self-conscious” of his “insensitivity” to religion. But this self-consciousness is not a product of any self-admitted methodological flaw in his work. His self-consciousness is instead a product of what he terms the “re-sacrilizing of the world.” Skinner sees this re-sacrilising as the reversal of Weberian and Marxist secular modernity which makes him uncomfortable. While his earlier work, Foundations of Modern Political Thought (1978), focused heavily on the relationship between religious principles and political change, Skinner says that his subsequent works are fashioned by his “boring atheism” from which his utter lack of attention to religious history stems.30

Is this supposed re-sacrilising a reversal of secularism—a phrase which should arouse suspicion—or is it the reorientation of religious and secular politics? Kashi demonstrates Skinner’s inability to answer or address this question. Skinner’s blind spot is indeed best remedied by the success of the Iranian Revolution, which laid the foundations for the production of modern Iranian intellectual history. The revolutionary lens with which Kashi is concerned is crucial for a diachronic intellectual history, which acknowledges and embraces a historical rupture while attempting to “see things their way,” that is, the author’s way, as a means for mapping conceptual change. Such scholarship of the modern period, however, must also engage with domestic political debates.

Engaging with contemporary domestic political debates is not an argument for nativism. Instead, it encourages the use of sources in which current debates on politics and conceptual change occur, as in the pages of Mehrnameh and other public forums. These forums demonstrate the very historical reckoning with which the present essay is concerned. And such a reckoning, not among European or American historians but among Iranians, in which religion plays a crucial political role—a role for material and social change over a theological one—demonstrates that the Iranian Revolution succeeded not only in establishing a new state but also a new ideational context for studying the history of political thought. The Revolution, in other words, reoriented the content and structure of global political authority in which concepts that were previously thought to have a secular history might as well possess a history without strict secular and religious divisions, let alone Western ownership.

Conclusion

The triumph of Khomeini’s revolutionary ideology over “Islamic Protestantism” or liberal iterations of Islam undoubtedly challenges the latter’s ability to effect great political change. Is not liberal freedom what all the world desires? Or perhaps, then, Khomeini “hijacked” the revolution and pushed it toward an alternative form of despotism? That such a revolution produced a challenge to dominant ways of writing history—or at least a condition in which Iranians are writing their own history in conversation with Western historians—should make anyone apprehensive of these questions. Despite deploying Skinner, whose method eschews religion’s importance, Kashi offers the potential to redefine sovereignty against theories that place religious authority in the annals of pre-Enlightenment thought. And despite his reception of a European intellectual historian, Kashi offers a critique only of Iranian authors without a critique of Skinner.

Unbeknownst to Skinner and his cohort, and regardless of Kashi’s intention, this dialogue nevertheless illustrates an emerging equilibrium in what is still often seen as a lopsided world—secular in the West contra religious in the East. In other words, Kashi’s reception reads contemporary intellectual history in the West (in all its parochialism) as a global discussion in which Iranians within Iran must participate. Although Skinner argues against the existence of perennial questions and strict contextualism, implicitly disallowing for a comparison between religious thought across time and space, Kashi’s insistence on Islam (even in its various forms)—as an autonomous force for change and the power to assert its own values—ironically allows for bolder scholarship than either Skinner or Kashi explicitly endorse. That the potential for such scholarship and dialogue, whatever its potential manifestations, comes from a post-revolutionary-“Islamic” Iran is a reckoning in itself.

Notes

- I would like to thank the editor of this issue, Neguin Yavari, as well as the ILEX Foundation for sponsoring this project and its publication. ↑

- For the original interview see Danny Millum, “Quentin Skinner,” in Making History: the changing face of the profession in Britain (18 April 2008). URL: https://www.history.ac.uk/makinghistory/resources/interviews/Skinner_Quentin.html. ↑

- Matīn Ghaffāriyān, “Butshikana usṭūra-hā-yi mudurn-i tārīkhī: darbāra-yi Ku’intīn Iskīnir bā bahāna-yi intishār-i kitāb bīnash-hā-yi ‘ilm-i siyāsat,” Mihrnāma 37 (2014): 268, at 268. ↑

- Mūsā Akramī, “Matn-i siyāsī dar maqām-i kunish-i siyāsī: Ku’intīn Iskīnir: nigāhī bih mabānī-i ravishshinākhtī va dastāvard-hā,” Mihrnāma 37(2014): 271-274. ↑

- Muḥammad-Javād Ghulām-Riżā Kāshī, “Farākhān-i Iskīnir bih maydān-i munāzi‘a Īrānī,” Mihrnāma 37 (2014): 269-270. ↑

- Ali Gheissari and Kaveh Cyrus-Sanandaji, “New Conservative Politics and Electoral Behavior in Iran,” in Contemporary Iran: Economy, Society, Politics, ed., Ali Gheissari (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 275-298, at 280. ↑

- See, for example, James Simpson, Permanent Revolution: The Reformation and the Illiberal Roots of Liberalism (Boston: Harvard University Press, 2019). ↑

- See the following interview with Skinner: Teresa Bejan, “Quentin Skinner: The Art of Theory Interview (2011),” The Art of Theory (2011). URL: https://www.uncanonical.net/skinner. ↑

- For an acknowledgment of the harms of intellectual history’s parochialism, see John Dunn, “Why We Need a Global History of Political Thought,” In Zusammenarbeit mit dem Husserl-Archiv Freiburg und dem Lehrstuhlfür Politische Philosophie, Theorie und Ideengeschichte, 21/11/2013. URL: http://www.husserlarchiv.de/materialien/JohnDunnConf/JohnDunnConf4. ↑

- Esmaeil Haddadian-Moghaddam, Literary Translation in Modern Iran: A Sociological Study (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2014), 118-19. ↑

- Muḥammad Qūchānī, “Trājidī-yi Prūtistāntīsm-i Islāmī: chigūna az iṣlāḥ-i dīnī, istibdād-i dīnī sar bar mī āvarad,” Mihrnāma, no. 36 (2014): 22-33, at 22. ↑

- Ibid., 22. ↑

- Ibid., 23. ↑

- Ibid., 24; Here Quchani quotes the dissident Taqi Rahmani. Ibid., 33. ↑

- Ibid., 33. ↑

- Kāshī, “Farākhān-i Iskīnir,” 270. ↑

- Ibid., 270. ↑

- Simpson, Permanent Revolution, 2-6. ↑

- David Armitage, “Every Great Revolution Is a Civil War,” in Scripting Revolution: A Historical Approach to the Comparative Study of Revolutions, edited by Keith Michael Baker and Dan Edelstein (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2015), 57-68 and 269-71. ↑

- Kāshī, “Farākhān-i Iskīnir,” 270. ↑

- Quentin Skinner, Visions of Politics: Volume 1: Regarding Method (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 1. ↑

- Ibid., 176; Ibid., 7. ↑

- Ibid., 179. ↑

- Ibid., 177. ↑

- Ibid., 7. ↑

- Ibid., 178. ↑

- Kāshī, “Farākhān-i Iskīnir,” 270. ↑

- Quchani recognises the existence of Shi‘i Salafists while Reinhard Schulze has labeled Shari‘ati the only Shi‘i Salafi. Qūchānī, Trādzidī-i Prūtistāntīsm-i Islāmī,” 33; Reinhard Schulze, A Modern History of the Islamic World, tr., Azizeh Azodi (New York and London: I.B. Tauris, 2002), 176-177. ↑

- See John Coffey, “Quentin Skinner and the Religious Dimension of Early Modern Political Thought,” in Seeing Things Their Way: Intellectual History and the Return of Religion, eds., Alister Chapman, John Coffey, and Brad S. Gregory (University of Notre Dame Press, 2009), 46-74; Neguin Yavari, Advice for the Sultan: Prophetic Voices and Secular Politics in Medieval Islam (London: Hurst, 2014), 143-155. Also see Yavari, Advice for the Sultan, on writing a history of non-Western political thought. ↑

- Bejan, “Quentin Skinner.” ↑