PDF

Download

Citations

Click and drag then release to select a passage to cite.

Annotations

How to submit annotations to Mizan Journal articles:

your work is published.

Search within

Ernst Bloch’s Aristotelian Left and a Monument for Avicenna

Preliminary Reflections on Arab Theory and the Materialism Debate

Image

Audio

Video

Chart or Graph

Ernst Bloch’s Aristotelian Left and a Monument for Avicenna

Preliminary Reflections on Arab Theory and the Materialism Debate

Introduction

Ibn Sina’s new mausoleum, built in 1952, was designed by Hooshang Seyhoun (d. 2014), a prominent Iranian architect. Image from Iran Tourism and Touring Organization. Photo: Hossein Alvandi.

I have been working for a while now on a research project I call “German-Jewish Echoes in 20th century Arabic Thought.” It explores how, when and why, which theories, methods and ideologies travel across the cultural and political barriers of the modern Mediterranean. I assess the effects of these intellectual translations at key turning points in contemporary history: from the postwar era and the anticolonial struggle to the end of the Cold War and the Arab uprisings of the 21st century. Arab theory, I argue in my research, developed as an intellectual project in response to the perceived failures of interwar Arab liberalism, to French and British colonialism, the destruction of Palestine since 1948, and leftist disenchantment with Nasserism and other iterations of pan-Arabism.

Meanwhile, Critical Theory has grappled—since its early days in the Frankfurt School—with the seemingly irrational rise of fascism and antisemitism; and as François Cusset and others have shown, “French Theory” was born in the settler colonial experience of French Algeria but became a thing when the writings of Michel Foucault (d. 1984), Jacques Derrida (d. 2004), Gilles Deleuze (d. 1995), Hélène Cixous and others gained traction in America since the global sixties. Arab, German and French theories, then, are historically and dialectically entangled through the postwar and postcolonial conjuncture. These three entangled traditions share a political impulse to challenge the grounds on which to philosophize.

I have written previously on Arab intellectual history and taught the Middle East and North Africa as a theory-producing region. The focus in this paper is not on diversifying the canon as much as on dissecting it. It forms part of a chapter in a work in progress that traces the influences of Abbasid/Andalusian philosophy on German and Arab theory production since the 1950s. I consider the distinctions between German and Arab Marxist materialism on medieval Islamic philosophy and their respective interactions with the works al-Farabi (d. 950), Ibn Sina (d. 1037), al-Ghazali (d. 1111), Ibn Rushd (d. 1198) and others . Here I compare Ernst Bloch’s (d. 1977) booklet Avicenna and the Aristotelian Left of 1952 to Husayn Muruwwah’s (d. 1987) 3,000-page long masterpiece Materialist Trends in Arabo-Islamic Philosophy published in 1979.1 Next I briefly discuss Muhammad Turki’s 2012 Arabic translation of Bloch’s book on Avicenna. Finally, I consider the contribution of this subversive materialist tradition to contemporary cross-cultural communication discourse.

Cover of Ernst Bloch’s Avicena and the Aristotelian Left, translated by Loren Goldman and Peter Thompson, New York: Columbia UP, 2019. Cover design: Milenda Nan Ok Lee. Image from Goodreads.

The clash of civilizations paradigm that has dominated cultural and foreign policy debates since the 1990s has spawned a number of chauvinist iterations. The charges of Islamo-fascism, Islamo-gauchisme and antisemitism, levied against any scholar of color and their affiliates who dare to criticize sacred white cows such as secularism or Zionism, more so in France and Germany but perhaps in Spain as well, are among them.

In this fraught atmosphere, a multi-directional alternative of a shared heritage across the Mediterranean is a crucial change of perspective. The point, however, cannot merely be to insert or assimilate Arabic-Islamic philosophy into the existing framework of Western history of philosophy. The point for Bloch and Muruwwah was to change the frame: to challenge Europeanist-nationalist and Islamicist-nationalist fallacies.

By Europeanists I have in mind a spectrum of scholars in/of Europe who insist, more or less dogmatically, on the autogenetic white, Christian identity of Europe. They tend to relegate any pre-colonial cultural exchange to ephemeralia or ornamentalia in the triumphal march of Europe. Islamicists deploy defensive arguments but end up emulating the Europeanists.

The Limits of Habermas

I would like to start with Jürgen Habermas for whom, coming of age in Germany in the 1980s, I have enormous respect. He is the social conscience of post-Nazi Germany, a stalwart champion of the ideals of European unification from which I have benefitted immensely. May he live as long as Hans-Georg Gadamer (d. 2002)! But from the perspective of my current research project, his oeuvre seems at sea, if not deeply flawed. My point is not to dissect his philosophical system, I am neither qualified nor interested. But it strikes me how removed his most recent magnum opus, Another History of Occidental Philosophy, is from the conceptual and historical realities I encounter and study; and how hostile to projects like mine, his work seems to have been since at least the 1990s.

Consider this excerpt from a frequently quoted interview from 1999:

Universalistic egalitarianism, from which sprang the ideals of freedom and a collective life in solidarity, the autonomous conduct of life and emancipation, the individual morality of conscience, human rights and democracy, is the direct legacy of the Judaic ethic of justice and the Christian ethic of love. This legacy, substantially unchanged, has been the object of continual critical appropriation and reinterpretation. To this day, there is no alternative to it. … Everything else is just idle postmodern talk.

Let that sink in! Habermas sketches Western civilization along a Jewish-Greek-Roman-Christian spectrum (Jerusalem, Athens, Rome – monotheism; science, and the republican tradition). At the same time, however, he pleads for a “reflective external impulse” which is supposed to encourage “intercultural communication.” But as we will see presently, unlike Bloch and Muruwwah, there is no room for Baghdad or Cordoba in Habermas’s public demand for intercultural dialogue.

Instead, he expresses his admiration for the immaculate conception of philosophical Europe in Thomas Aquinas (d. 1274):

[Aquinas] represents a form of spirit [Gestalt des Geistes] which vouches for its own authenticity from within itself. [But] I see a chance in the encounter with ‘strong’ traditions from elsewhere to become more fully aware of our Judeo-Christian transmissions. This impetus for self-reflection is what makes intercultural communication possible. All participants must be made aware of the particularity of their own intellectual premises, before their shared discursive premises, interpretations and value orientation can crystallize.2

I do not wish to overread the idiosyncrasy of this passage. But what value does Habermas see in communicating with “strong” non-Western traditions, presumably Islam? Why disqualify “weak” traditions and to whom do those belong anyway?

In Habermas’s new 2,000-page long book, there is no room for the most obvious strong “non-Western tradition,” Islam. Given that 9/11 was a key impetus for Habermas to ask anew the Gretchenfrage – the question of religion – it seems a glaring omission. It may be said in his defense that excluding Islamic metaphysics is a show of respect for a tradition he has not studied. But then it is odd that Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism do feature as axial philosophies in his book. Perhaps they are included because they are stronger traditions? I am not sure what to make of this.

I submit that here intercultural dialogue is instrumentalized and ideological in all the ways Max Horkheimer (d. 1973) and Theodor Adorno (d. 1969) have warned us against a long time ago. Habermas valorizes the Enlightenment and the encounter with the non-West so that Europeans can develop a stronger identification with the post-Nazi mantra of Judeo-Christian harmony. This transcendental move keeps much out and fails to fully acknowledge the constitutive other in the construction of the self, what his mentor Adorno called the non-identity of identity and “French theory” adopted as a hallmark of poststructuralism.

My purpose in this essay is much more modest than Habermas’s. I would like to introduce you to Ernst Bloch and Husayn Muruwwah, two maverick Communist philosophers who have offered alternative, non-identitarianist histories of philosophy. I am not interested in them because they are Communists but because their accounts do not begin with Aquinas in the same way that those by Europeanists’ such as Habermas always do. Instead, both make a case for Ibn Sina, the Latin Avicenna popularized in Noah Gordon’s Medicus, as the missing link between Aristotle and Aquinas and as the starting point of a suppressed philosophical tradition that they call, avant le mot, materialist.

Cover Image for Arabic Translation of Avicenna and the Aristotelian Left. Book made available from noor-books.com.

Hamadan 1952

My journey of rediscovery begins in the Western Iranian provincial capital Hamadan, where an impressive new mausoleum for the philosopher and medical scholar Ibn Sina was inaugurated in May 1952 to commemorate his passing one thousand years ago. Ibn Sina’s vast opus was the culmination of philosophical transformations in Late Antiquity’s final, “exegetical” age.3 The centre of Greek learning had long moved from Athens to Ptolemaic Alexandria, where the Christian theologians Clement (d. ca 215) and Origen (d. ca 253) wrote important commentaries on the Bible and Platonized Christianity; here Plotinus (d. 270) founded Neo-Platonism, wherein he and his student Porphyry (d. 301) harmonized Aristotle and Plato.4 Alexandria peaked in the 4th century CE, until a mob of angry monks killed the mathematical and philosophical genius Hypatia in 415 AD.

Aristotelianism and neo-Platonism then migrated to Antioch and Harran. Here the Greek texts were translated into Syriac to establish a flourishing, 200 year-long philosophical tradition. It was this Syriac tradition that made possible the emergence of falsafa – the pursuit of Abbasid/Andalusian philosophy – cosmology, logic, epistemology and metaphysics – on Greek grounds, but in Arabic, in and around the Abbasid capital Baghdad. And unacknowledged by Habermas, Ibn Sina in Baghdad and Ibn Rushd in Cordoba built the Aristotelian foundations for medieval Scholasticism, which allowed for the Renaissance to take off at the University of Paris, in Florence and elsewhere.

Ibn Sina’s arguments for the distinction between essence and existence had lasting (again, unacknowledged) echoes in European philosophy, not least in Aquinas, Gottfried Leibniz (d. 1716) and in Martin Heidegger (d. 1976). His proof of God as “the necessary existent” was one of his most influential and controversial contributions to theology and philosophy. Ibn Sina reasoned that there can be only one necessary existent, since if they were two or more, then some external cause would be needed to distinguish them from one another.

The necessary existent must also be immaterial, lest it depend for its existence on its matter; it must be perfectly good, too, since goodness is implied by actual existence.5 Avicenna made God not just necessarily existent in itself, but necessary in every way. This meant that God could no longer be conceived as a gratuitously willing being or agent who creates, rewards, and punishes as it pleases. God as necessary existent is defined by its knowledge of all things, not by its creation of and interventions in the universe.

In this matter, Avicenna is hardly a materialist. So, did Bloch and Muruwwah misconstrue his argument? Maybe. Did they twist the evidence to suit their communist ideology? Certainly. … But even if they did, their arguments are nevertheless worth considering. A sympathetic reading of Abbasid/Andalusian philosophy is certainly preferable to liberal hostility or Europeanist erasure.

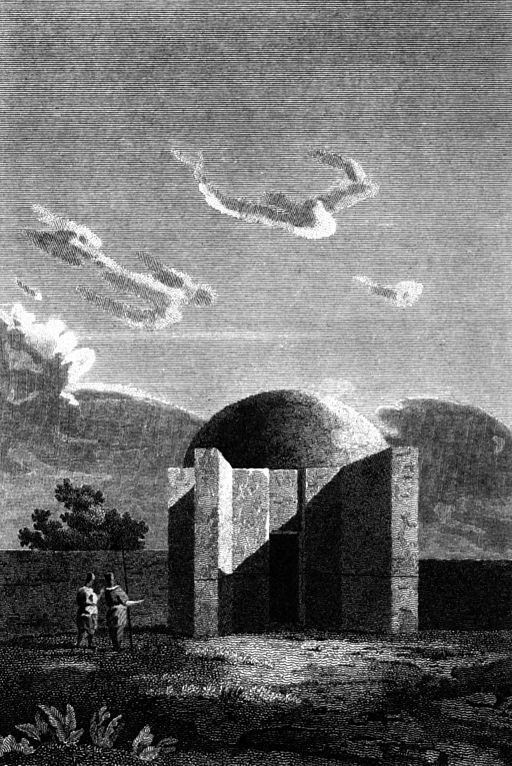

The old mausoleum by Charles Heath, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

But let’s return to Hamadan. What is important here about 1952 is that the commemoration was organized and staged by the Iranian Peace Committee of the Tudeh party – remarkable in itself for we do not necessarily associate communists and socialists with an interest in Abbasid/Andalusian philosophy. It was this event in Hamadan that inspired Ernst Bloch and Husayn Muruwwah, independently from each other, to invoke the revolutionary potential of Ibn Sina’s natural metaphysics.6

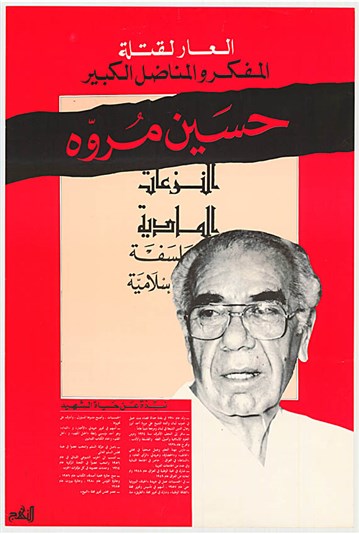

The Lebanese communist Husayn Muruwwah was born in Jabal ‘Amil in southern Lebanon in 1910 and was expected to train as a cleric in the seminary of Najaf. After stations in Damascus, Beirut and Baghdad he returned to Najaf to complete his religious education as a mujtahid in 1938. But what he discovered while in Iraq was, first, Taha Hussein (d. 1973) and the liberal Nahda tradition, and soon, Karl Marx (d. 1883) and Vladimir Lenin (d. 1924). He was drawn to the Iraqi Left after WWII and eventually became a communist cadre.7 He was expelled from Iraq in 1949 for this affiliation and after he had participated in the national protests against the extension of British rule.

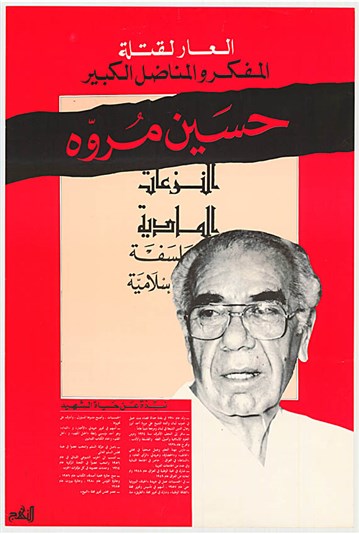

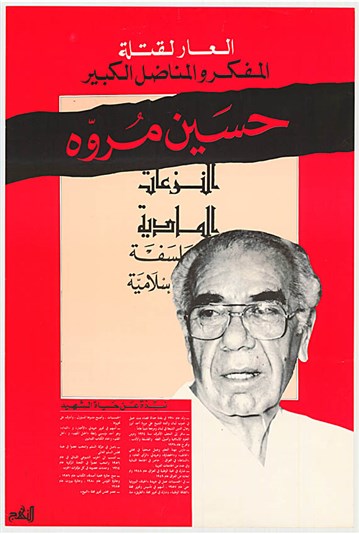

Poster, “Shame on the murderers of the great thinker and militant Hussein Mroueh,” 1987. From the collection of Zeina Maasri. Image from the archive of Signs of Conflict: Political Posters of Lebanon’s Civil War (1975-1990).

Muruwwah returned to Beirut from where he helped launch “the project of our age” (mashru‘ al-‘umr): the Cairo-based al-Thaqafa al-Wataniyya in 1952. This engaged journal gave a programmatic platform to the question of turath, namely, the political force of the Arabo-Islamic heritage for the present.

In one of its first issues –May 1952 – Muruwwah wrote a five-page article, “Ibn Sina: A Progressive Idea.”8 This article referenced the Ibn Sina celebrations in Baghdad “two weeks ago,” and Muruwwah urged his readers to embrace Ibn Sina’s contribution to the “Arabic intellectual heritage …, and as the golden link in the intellectual chain of human civilization in general.” Since the Nahda period of the nineteenth century, Islamic reformers have returned to the heritage of theology and philosophy “by asserting the primacy of the ‘spiritual-moral’ foundations” of Muslim society.9 Muruwwah now warned that this idealist move was based on a static and authenticist conception of the past, and it left unchallenged the material effects of colonialism in the present. Progressives, in particular, ought to study Ibn Sina’s life and work, Muruwwah wrote, not just because he was a polymath, but also because he “combined metaphysics with political engagement and was persecuted for it.” And for all his neo-platonic abstraction, Ibn Sina’s philosophy of nature was materialist. In sum, he was “certainly a living embodiment of a sublime progressive idea called the ‘unity’ of life.”10

Let me turn to our second ‘Aristo-gauchiste.’ Ernst Bloch learnt about the Hamadan celebrations from a Soviet periodical and published his Avicenna and the Aristotelian Left that same year. This professor of philosophy, theologian of revolution, this warm-stream Marxist, and Communist enfant terrible of the Frankfurt School had engaged with Abbasid/Andalusian philosophy for a long time. As early as 1936, he wrote to Max Horkheimer that he had compiled a “materialist reader” for himself of texts by “non-mechanistic materialists … like … [Giordano] Bruno, Ibn Gabirol and Ibn Rushd.” Bloch’s biographer even speculates that the impetus for this interest could have been Bloch’s trip to Tunisia back in 1926.

Both Bloch and Muruwwah returned to Ibn Sina and the materialism debate in their final major works in the 1970s. But before we can get to the content of this debate, I want to ask: What did a materialist reading of Abbasid/ Andalusian philosophy achieve for Bloch and Muruwwah? Why did they bother, as Marxists, to return to the metaphysics of Ibn Sina?

For one, both Bloch and Muruwwah challenged the tunnel visions of their respective communities of discourse in moments of crisis. What was at stake for Muruwwah was finding a method to overcome past mystifications of competing Islamic, nationalist and liberal nostalgias at a time of a deep “crisis of language and life” in the Arab world. What he was searching for in this article and found the answer for in his 1979 masterpiece Materialist Trends in Arabo-Islamic Philosophy, was a method of totality, a method of concrete universals: His answer to the fragmented conceptions of life wrought by capitalism and colonialism was, I argue, a type of Dialectical Materialism grounded in Ibn Sina’s natural philosophy.

There has been a consistent aversion to materialism since Leibniz first coined the term around 1700, to refer to mechanistic interpretations of change around.11 But Bloch found in Ibn Sina the figure of thought to salvage what Stalinist Dialectical Materialism had perverted, and to revive materialist conceptions of Nature and Being as a compound of matter and form (viz. Aristotle’s Hylomorphism).12 It is not mechanical scientific laws of nature that determine human existence, rather Being is open, full of potentiality, it is the result of inchoate dialectical entanglement of consciousness and nature, essence and existence, objectivity and subjectivity, body and soul.

Aristotle-Avicenna-Bloch isnād

To Aristotle, everything that changes must consist of matter. Matter is that out of which natural substances are made – say wood; and form is what the senses perceive – say a tree or a chair. But according to Bloch, Aristotle’s matter merely contains passive possibility, which only finds actualization in form. It was his “friend Ibn Sina”, who offered Bloch a way out, to identify in matter itself metaphysical excess, emancipatory spirit and anticipatory force. Thus, on what Bloch labelled “the Aristotelian Left’s” view, matter is not inert or activated externally, but self-generating. Bloch’s interpretative maneuver is no doubt self-serving. But Bloch’s Avicennan upgrade of Aristotle’s hylomorphism is important nevertheless, not least because one may well derive green Marxism or feminist philosophy from his move.13 This tradition offers a non-anthropocentric form of what Paul Gilroy today calls “planetary humanism,” in which nature and the material world both enable and constrain emancipation.

Genealogy of the “Aristotelian Left”

Bloch brings, somewhat impishly, a hidden ‘peripatetic left’ into being. This tradition leads from late Greek commentators of Aristotle, such as Alexander of Aphrodisias (fl. ca 200), the “protopantheist” who “initiated the concept of the highest potency of matter,” to Avicenna’s “ascendant naturalization,” advanced by the Andalusian-Jewish philosopher Ibn Gabirol (11th century) in the concept of materia naturalis, to Ibn Tufayl’s auto-didactical, philosophical novel Hayy ibn Yaqzan(The Living, Son of the Wakesome), which influenced, via Daniel Defoe’s (d. 1731) Robinson Crusoe, the European enlightenment. Bloch’s isnād culminates, first, with Ibn Rushd who showed matter as eternally in flux and alive in the form of “natura naturans”– self-created nature. For Bloch, Abbasid/Andalusian philosophy presented the first step in the conception of nature as independent from divine fiat and human mastery. And, finally, Giordano Bruno (d. 1600) radicalized matter in the 16th century “as a fructifying and fecund universal life.” Bloch claims that this Aristotelian Left represents a bulwark against “the spirit of otherworldliness”.

The first to take exception to Avicenna‘s main theories—eternal nature of matter, the incorruptibility of the law of causality, the non-resurrection of the dead, and “the subordination of faith in Scripture to cognitive truth—was, of course, al-Ghazali (d. 1111). Following Ibn Rushd’s death, Muslim and Christian scholasticism pilloried the idea that “the active potentiality of matter intermingled with divine potency.” According to Bloch, “Thomas Aquinas by contrast, the world – only ever the creation, never creative – largely withdraws.” After Aquinas, the “Aristotelian Right” considered matter sinful, subordinated it to form, and championed divine authority and feudal-clerical rule.14

Again, Ibn Sina was no natural ally of Bloch’s renewal of materialism project; think of Ibn Sina’s famous floating man, the thought experiment where he claimed that humans had cognition and self-awareness even without somatic perceptions of their environment. Hardly a materialist argument. Nevertheless, Bloch, like Muruwwah, insisted in 1952 that “Avicenna was a doctor and not a monk, a natural philosopher not a theologian.” If in the Axial Age, mythos was transformed into logos, then in the Exegetical Age of Late Antiquity, Ibn Sina “transvalued religious allegories into philosophical concepts.”15 Ibn Sina not only had the world historical distinction of having read Aristotle as a natural philosopher, Bloch later claimed in his The Principle of Hope that “without [Avicenna and the] Aristotle-to-Bruno legacy, Marx would not have been able to upend the Hegelian world idea so naturally.”16

Rediscovering Avicenna and the Aristotelian Left in Arabic

Bloch’s work on Avicenna also furnishes a fruitful approach for studying debates about Orientalism and Islam. Bloch’s recent Arabic translator, Mohamed Turki, believes the book has potential for intercultural dialogue. This makes sense, especially in the context of culturalist tendencies from Huntington to Habermas, but also in certain decoloniality debates that are fashionable these days. But for the moment, I am more interested in two further points that Turki raises in his introduction. First, Turki points out that modern Orientalism perpetuated the marginalization and suppression of the Aristotelian Left tradition. Turki sees Bloch’s book as a subversive act of counter-memory or a genealogical method at work. Bloch claims that Europe owes a debt to “Iranian-Arabic brilliance,” for “it is Ibn Sina, along with Ibn Rushd, who – unlike Western scholars – represent one of the sources of our enlightenment and, above all, of a most singular materialist vitality, developed out of Aristotle in a non-Christian manner.” Bloch was enraged that Max Horten, who translated Avicenna into German in the early 20th century, labeled the anti-Orthodox Averroes as “an apologist for the Koran.”

The second noteworthy point in Turki’s introduction regards the persistence of the Aristotle-Ibn Sina-Ernst Bloch isnādamong the Arab Left in the 20th century. Turki highlights a number of studies including Tayib Tizini’s German doctoral dissertation Mashru‘ ru’ya jadida lil-fikr al-arabi fil-‘asr al-wasīt, as well as the red Mujtahid Muruwwah’s Materialist Tendencies. However, despite elective affinities, neither Tizini nor Muruwwah engage explicitly with Bloch’s work on Avicenna.

Muruwwah, in particular, moved in a somewhat different problem space than Bloch, even though both invoked Ibn Sina after the same communist festivities in 1952. Muruwwah addressed a deep “methodological crisis” which he ascribed to modern Arab thought. According to Muruwwah, Arab historians merely praised the lost classical Arab genius or got lost in isolated textual details. Conversely, modern Arab philosophers and Orientalists had no concept of the socio-economic context of philosophical development. Moreover, the resurgent Salafi discourse of the Anwar Sadat (d. 1981) years denied the central role Aristotle played in Arab/Islamic turath on account of the useful decolonial fiction of the European identity of ancient Greece.

Everything is connected and entangled, Muruwwah claims: past and present, text and context, content and form, epistemology and materiality, as well as the Greek, Arabo-Islamic and European heritage. A properly radical materialist philosophy links these tendencies dialectically. Muruwwah hoped that Arab philosophical engagement with Marx and Engels would offer the much-needed alternative to essentialist theological and abstract juridical conceptions of life, religion and art. But when the almost 80-year-old Muruwwah was assassinated by Islamist militants in the chaos of the Lebanese civil war, it effectively marked the end of the Arab Left.

Conclusion

The 21st century has witnessed a revival of interest in Materialism in general and the works of Muruwwah and Bloch in particular. Ibn Sina and Ibn Rushd have elicited both appreciation and anxiety since the time of al-Ghazali and Aquinas.

For all their heterodoxy, neither Avicenna nor Bloch’s and Muruwwah’s apocryphal Aristotelian Left saw philosophy as antithetical to religion. Avicenna considered philosophy as the path to human self-awareness and to the acceptance of God as necessary existent (wājib al-wujūd), as the all-knowing and first cause of being. Bloch had no time for church fathers and orthodoxy in general, as he saw both in cahoots with political power. Conversely, his metaphysical and theological tendencies made for his pariah status not just in the Soviet Union but also among Western Marxists. His unorthodox and instrumentalist reading of Ibn Sina hardly makes him a serious scholar of Islam. But in the spirit of a sympathetic reading, I credit Bloch with conjuring up a breach the epistemological walls Europeanist systems of philosophy have erected.

Husayn Muruwwah, by contrast, was a very serious scholar of Islam. And on matters of substance, he came to similar conclusions as Bloch. Since his first forays into Ibn Sina in 1952, he continuously worked on the question of method.17 Muruwwah warned that the Abbasid/Andalusian legacy for the present struggle has not really been dealt with properly by contemporary revolutionaries, Arab intellectuals and academics.18

The above is the finest of what ‘Aristo-gauchisme’ has had to offer, if you excuse my impishness. Both Bloch and Muruwwah have offered critiques of the history of philosophy that deserve our serious attention. And they did so not as theoreticians but as philosophers; not as what Habermas labeled idle postmodern theorists, but as creative system builders in their own right. Orthodox Communism may be dead, but we have much to learn from the thought of communist mavericks such as Bloch and Muruwwah in the twilight of liberalism.

My exhortation to the serious study of Bloch’s and Muruwwah’s grounding of European and Islamic philosophy might reek of presentism, too: Should European universities adjust their tried and tested curricula just because of recent demographic changes? Shouldn’t we strengthen, with Habermas, our commitment to Europeanist histories of philosophy? To this rhetorical question my paper provides a tentative two-fold answer: a) the Europeanist version is actually historically inaccurate, as the exclusion of Avicenna et al was ideological, or at least ideological complacency, to begin with; and b) philosophical and cultural traditions intermingled from the very beginning. Arabo-Islamic philosophy was not the absolute other of what became European philosophy in the early modern period. Arguably, Arabo-Islamic philosophy was no less “open to Reason,” to borrow Souleymane Bachir Diagne’s felicitous book title,19 than Aquinas and what Bloch called the Aristotelian Right that have dominated Europeanist philosophy ever since.20

Notes

- Bloch, Ernst [1952], Avicenna und die Aristotelische Linke (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1963); Husayn Muruwwah, Naza‘at al-maddiyya fi al-falsafa al-‘arabiyya al-islamiyya, 4 vols. (Beirut: Dar al-Farabi, 1978). ↑

- Jürgen Habermas, “Ein Gespräch über Gott und die Welt,” in Zeit der Übergänge. Kleine politische Schriften IX (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2001), pp. 173-96. ↑

- Gareth Fowden, Before and After Muhammad: The First Millenium Refocused (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014). ↑

- For more on this see Peter Adamson, Interpreting Avicenna: Critical Essays (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013) and Cristina D’Ancona Costa, “Avicenna and the Liber de Causis: A Contribution to the Dossier,” Revista Española de Filosofía Medieval 7 (2000), pp. 95-114. ↑

- In her thesis, Kara Richardson claims that “Avicenna also holds that the cause of the existence of contingent things is an incorporeal principle, which he describes as an agent who ‘bestows forms.’” I argue that Avicenna fails to resolve the tension between this claim and his commitment to an Aristotelian account of generation; see Kara Richardson, “Avicenna on Teleology: Final Causation and Goodness,” in Teleology, ed. Jeffrey K. McDonough (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020), pp. 71-89. ↑

- Henry Corbin, Avicenne et le récit visionnaire (Téhéran: Société des Monuments Nationaux, 1952-54).. That same year, two previous professors at my university published works on Avicenna: Emil L. Fackenheim, “Ibn Sina: The Man and his Work,” Middle Eastern Affairs 3 (1952), pp. 265-71 and G. M. Wickens (ed.), Avicenna: Scientist & Philosopher: A Millenary Symposium (London: Luzac, 1952). See also Fazlur Rahman (ed.), Avicenna’s Psychology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1952). The Indian Iran society held a congress that year and published its proceedings Avicenna commemoration volume in 1956. ↑

- Louis Allday, “Remembering Husayn Muruwwah, the ‘Red Mujtahid,’” Jadaliyya, 16 February 2017; https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/34028 ↑

- Husayn Muruwwah, “Ibn Sina: A Progressive Idea,” Al-Thaqafa al-Wataniyya, May 1952. Reprinted in his Turathuna, kayfa na‘rifuhu (Beirut: Mu’assasa al-Abhath al-‘Arabiyya, 1985), pp. 31-35. ↑

- Rula Jurdi Abisaab, “Deconstructing the Modular and the Authentic: Husayn Muroeh’s Early Islamic History,“ Critique: Critical Middle Eastern Studies 17 (2008), 239-59. Here: 241. ↑

- Husayn Muruwwah (1952): “…was connected to real practical life, indeed, a strange, intense connection. However, he attained the intensity of his connection to life through his engagement with it. He was completely passionate about it, accepting its pleasures to the degree of gluttony, pursuing its consequences and burdens most ruthlessly, relishing to acquire it, bearing its fate most intensely and strongly.” ↑

- Julia Borcherding, “Reflection, Intelligibility, and Leibniz’s Case Against Materialism,” Logical Analysis and the History of Philosophy 21 (2018): 44-68. ↑

- Bloch’s book on Avicenna and his later summa Das Materialismusproblem were primarily directed against the 19th century controversy about Aristotle’s Hylomorphism (being = compound of matter and form) between physicalists, idealists and sensualists in Hegel’s wake, a debate that expressed a deep identity crisis in German philosophy at the time. Against this background, Bloch’s project for a renewal of materialism on an Avicennan foundation appears pertinent, since for Bloch, the Iranian commemoration of 1952 was significant as an act of actualizing a humanist materialism, as a hope-endowing, salvific practice. ↑

- In fact, Ibn Rushd’s “womb of matter” and Bloch’s idea that matter derives etymologically from mater-mother, may support a feminist critique of Aristotle’s Generation of Animals. This book was, according to Emanuella Bianchi, the foundational text of Western patriarchal metaphysics and sexist notions of heredity. Aristotle identified the female as the source of matter for the offspring, while the male provides the principle of motion, generation and form. Aristotle’s intuition that the masculine operates upon the feminine, the active upon the passive, the semen upon the womb, got him into philosophical trouble explaining female offspring as “material mishaps” or accidents of nature. Bloch’s insistence on the active and procreational potential of matter effectively emasculates the power of form. ↑

- Bloch, Avicenna und die Aristotelische Linke, pp. 11-12, 16. ↑

- Ibid., pp. 15, 23-24. ↑

- Bloch, Ernst [1959], The Principle of Hope, vol. 1 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995), p. 208. ↑

- Muruwwa, Naza‘at al-maddiyya, pp. 23-32. ↑

- Muruwwa, Naza‘at al-maddiyya, pp. 18-19. Either historians worked on isolated historical details, or they produced grand commonplaces about the scientific genius of the Arabs. Representative of this popular approach was the Lebanese historian ‘Umar Farrukh’s ‘Abkariyya al-‘arab fi al-’ilm wa al-falsafa (1945), published as The Arab Genius in Science and Philosophy by the American Council of Learned Societies, Washington, 1954. Arab philosophers, such as ‘Abd al-Rahman Badawi for example, merely offered idealist and metaphysical theories and were oblivious to historical dynamics and socio-economic contexts. ↑

- Souleyman Bachir Diagne, Open to Reason: Muslim Philosophers in Conversation with the Western Tradition (New York: Columbia University Press, 2018). ↑

- Bloch, Avicenna und die Aristotelische Linke, pp. 46-7. ↑

Ernst Bloch’s Aristotelian Left and a Monument for Avicenna

Preliminary Reflections on Arab Theory and the Materialism Debate

Introduction

Ibn Sina’s new mausoleum, built in 1952, was designed by Hooshang Seyhoun (d. 2014), a prominent Iranian architect. Image from Iran Tourism and Touring Organization. Photo: Hossein Alvandi.

I have been working for a while now on a research project I call “German-Jewish Echoes in 20th century Arabic Thought.” It explores how, when and why, which theories, methods and ideologies travel across the cultural and political barriers of the modern Mediterranean. I assess the effects of these intellectual translations at key turning points in contemporary history: from the postwar era and the anticolonial struggle to the end of the Cold War and the Arab uprisings of the 21st century. Arab theory, I argue in my research, developed as an intellectual project in response to the perceived failures of interwar Arab liberalism, to French and British colonialism, the destruction of Palestine since 1948, and leftist disenchantment with Nasserism and other iterations of pan-Arabism.

Meanwhile, Critical Theory has grappled—since its early days in the Frankfurt School—with the seemingly irrational rise of fascism and antisemitism; and as François Cusset and others have shown, “French Theory” was born in the settler colonial experience of French Algeria but became a thing when the writings of Michel Foucault (d. 1984), Jacques Derrida (d. 2004), Gilles Deleuze (d. 1995), Hélène Cixous and others gained traction in America since the global sixties. Arab, German and French theories, then, are historically and dialectically entangled through the postwar and postcolonial conjuncture. These three entangled traditions share a political impulse to challenge the grounds on which to philosophize.

I have written previously on Arab intellectual history and taught the Middle East and North Africa as a theory-producing region. The focus in this paper is not on diversifying the canon as much as on dissecting it. It forms part of a chapter in a work in progress that traces the influences of Abbasid/Andalusian philosophy on German and Arab theory production since the 1950s. I consider the distinctions between German and Arab Marxist materialism on medieval Islamic philosophy and their respective interactions with the works al-Farabi (d. 950), Ibn Sina (d. 1037), al-Ghazali (d. 1111), Ibn Rushd (d. 1198) and others . Here I compare Ernst Bloch’s (d. 1977) booklet Avicenna and the Aristotelian Left of 1952 to Husayn Muruwwah’s (d. 1987) 3,000-page long masterpiece Materialist Trends in Arabo-Islamic Philosophy published in 1979.1 Next I briefly discuss Muhammad Turki’s 2012 Arabic translation of Bloch’s book on Avicenna. Finally, I consider the contribution of this subversive materialist tradition to contemporary cross-cultural communication discourse.

Cover of Ernst Bloch’s Avicena and the Aristotelian Left, translated by Loren Goldman and Peter Thompson, New York: Columbia UP, 2019. Cover design: Milenda Nan Ok Lee. Image from Goodreads.

The clash of civilizations paradigm that has dominated cultural and foreign policy debates since the 1990s has spawned a number of chauvinist iterations. The charges of Islamo-fascism, Islamo-gauchisme and antisemitism, levied against any scholar of color and their affiliates who dare to criticize sacred white cows such as secularism or Zionism, more so in France and Germany but perhaps in Spain as well, are among them.

In this fraught atmosphere, a multi-directional alternative of a shared heritage across the Mediterranean is a crucial change of perspective. The point, however, cannot merely be to insert or assimilate Arabic-Islamic philosophy into the existing framework of Western history of philosophy. The point for Bloch and Muruwwah was to change the frame: to challenge Europeanist-nationalist and Islamicist-nationalist fallacies.

By Europeanists I have in mind a spectrum of scholars in/of Europe who insist, more or less dogmatically, on the autogenetic white, Christian identity of Europe. They tend to relegate any pre-colonial cultural exchange to ephemeralia or ornamentalia in the triumphal march of Europe. Islamicists deploy defensive arguments but end up emulating the Europeanists.

The Limits of Habermas

I would like to start with Jürgen Habermas for whom, coming of age in Germany in the 1980s, I have enormous respect. He is the social conscience of post-Nazi Germany, a stalwart champion of the ideals of European unification from which I have benefitted immensely. May he live as long as Hans-Georg Gadamer (d. 2002)! But from the perspective of my current research project, his oeuvre seems at sea, if not deeply flawed. My point is not to dissect his philosophical system, I am neither qualified nor interested. But it strikes me how removed his most recent magnum opus, Another History of Occidental Philosophy, is from the conceptual and historical realities I encounter and study; and how hostile to projects like mine, his work seems to have been since at least the 1990s.

Consider this excerpt from a frequently quoted interview from 1999:

Universalistic egalitarianism, from which sprang the ideals of freedom and a collective life in solidarity, the autonomous conduct of life and emancipation, the individual morality of conscience, human rights and democracy, is the direct legacy of the Judaic ethic of justice and the Christian ethic of love. This legacy, substantially unchanged, has been the object of continual critical appropriation and reinterpretation. To this day, there is no alternative to it. … Everything else is just idle postmodern talk.

Let that sink in! Habermas sketches Western civilization along a Jewish-Greek-Roman-Christian spectrum (Jerusalem, Athens, Rome – monotheism; science, and the republican tradition). At the same time, however, he pleads for a “reflective external impulse” which is supposed to encourage “intercultural communication.” But as we will see presently, unlike Bloch and Muruwwah, there is no room for Baghdad or Cordoba in Habermas’s public demand for intercultural dialogue.

Instead, he expresses his admiration for the immaculate conception of philosophical Europe in Thomas Aquinas (d. 1274):

[Aquinas] represents a form of spirit [Gestalt des Geistes] which vouches for its own authenticity from within itself. [But] I see a chance in the encounter with ‘strong’ traditions from elsewhere to become more fully aware of our Judeo-Christian transmissions. This impetus for self-reflection is what makes intercultural communication possible. All participants must be made aware of the particularity of their own intellectual premises, before their shared discursive premises, interpretations and value orientation can crystallize.2

I do not wish to overread the idiosyncrasy of this passage. But what value does Habermas see in communicating with “strong” non-Western traditions, presumably Islam? Why disqualify “weak” traditions and to whom do those belong anyway?

In Habermas’s new 2,000-page long book, there is no room for the most obvious strong “non-Western tradition,” Islam. Given that 9/11 was a key impetus for Habermas to ask anew the Gretchenfrage – the question of religion – it seems a glaring omission. It may be said in his defense that excluding Islamic metaphysics is a show of respect for a tradition he has not studied. But then it is odd that Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism do feature as axial philosophies in his book. Perhaps they are included because they are stronger traditions? I am not sure what to make of this.

I submit that here intercultural dialogue is instrumentalized and ideological in all the ways Max Horkheimer (d. 1973) and Theodor Adorno (d. 1969) have warned us against a long time ago. Habermas valorizes the Enlightenment and the encounter with the non-West so that Europeans can develop a stronger identification with the post-Nazi mantra of Judeo-Christian harmony. This transcendental move keeps much out and fails to fully acknowledge the constitutive other in the construction of the self, what his mentor Adorno called the non-identity of identity and “French theory” adopted as a hallmark of poststructuralism.

My purpose in this essay is much more modest than Habermas’s. I would like to introduce you to Ernst Bloch and Husayn Muruwwah, two maverick Communist philosophers who have offered alternative, non-identitarianist histories of philosophy. I am not interested in them because they are Communists but because their accounts do not begin with Aquinas in the same way that those by Europeanists’ such as Habermas always do. Instead, both make a case for Ibn Sina, the Latin Avicenna popularized in Noah Gordon’s Medicus, as the missing link between Aristotle and Aquinas and as the starting point of a suppressed philosophical tradition that they call, avant le mot, materialist.

Cover Image for Arabic Translation of Avicenna and the Aristotelian Left. Book made available from noor-books.com.

Hamadan 1952

My journey of rediscovery begins in the Western Iranian provincial capital Hamadan, where an impressive new mausoleum for the philosopher and medical scholar Ibn Sina was inaugurated in May 1952 to commemorate his passing one thousand years ago. Ibn Sina’s vast opus was the culmination of philosophical transformations in Late Antiquity’s final, “exegetical” age.3 The centre of Greek learning had long moved from Athens to Ptolemaic Alexandria, where the Christian theologians Clement (d. ca 215) and Origen (d. ca 253) wrote important commentaries on the Bible and Platonized Christianity; here Plotinus (d. 270) founded Neo-Platonism, wherein he and his student Porphyry (d. 301) harmonized Aristotle and Plato.4 Alexandria peaked in the 4th century CE, until a mob of angry monks killed the mathematical and philosophical genius Hypatia in 415 AD.

Aristotelianism and neo-Platonism then migrated to Antioch and Harran. Here the Greek texts were translated into Syriac to establish a flourishing, 200 year-long philosophical tradition. It was this Syriac tradition that made possible the emergence of falsafa – the pursuit of Abbasid/Andalusian philosophy – cosmology, logic, epistemology and metaphysics – on Greek grounds, but in Arabic, in and around the Abbasid capital Baghdad. And unacknowledged by Habermas, Ibn Sina in Baghdad and Ibn Rushd in Cordoba built the Aristotelian foundations for medieval Scholasticism, which allowed for the Renaissance to take off at the University of Paris, in Florence and elsewhere.

Ibn Sina’s arguments for the distinction between essence and existence had lasting (again, unacknowledged) echoes in European philosophy, not least in Aquinas, Gottfried Leibniz (d. 1716) and in Martin Heidegger (d. 1976). His proof of God as “the necessary existent” was one of his most influential and controversial contributions to theology and philosophy. Ibn Sina reasoned that there can be only one necessary existent, since if they were two or more, then some external cause would be needed to distinguish them from one another.

The necessary existent must also be immaterial, lest it depend for its existence on its matter; it must be perfectly good, too, since goodness is implied by actual existence.5 Avicenna made God not just necessarily existent in itself, but necessary in every way. This meant that God could no longer be conceived as a gratuitously willing being or agent who creates, rewards, and punishes as it pleases. God as necessary existent is defined by its knowledge of all things, not by its creation of and interventions in the universe.

In this matter, Avicenna is hardly a materialist. So, did Bloch and Muruwwah misconstrue his argument? Maybe. Did they twist the evidence to suit their communist ideology? Certainly. … But even if they did, their arguments are nevertheless worth considering. A sympathetic reading of Abbasid/Andalusian philosophy is certainly preferable to liberal hostility or Europeanist erasure.

The old mausoleum by Charles Heath, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

But let’s return to Hamadan. What is important here about 1952 is that the commemoration was organized and staged by the Iranian Peace Committee of the Tudeh party – remarkable in itself for we do not necessarily associate communists and socialists with an interest in Abbasid/Andalusian philosophy. It was this event in Hamadan that inspired Ernst Bloch and Husayn Muruwwah, independently from each other, to invoke the revolutionary potential of Ibn Sina’s natural metaphysics.6

The Lebanese communist Husayn Muruwwah was born in Jabal ‘Amil in southern Lebanon in 1910 and was expected to train as a cleric in the seminary of Najaf. After stations in Damascus, Beirut and Baghdad he returned to Najaf to complete his religious education as a mujtahid in 1938. But what he discovered while in Iraq was, first, Taha Hussein (d. 1973) and the liberal Nahda tradition, and soon, Karl Marx (d. 1883) and Vladimir Lenin (d. 1924). He was drawn to the Iraqi Left after WWII and eventually became a communist cadre.7 He was expelled from Iraq in 1949 for this affiliation and after he had participated in the national protests against the extension of British rule.

Poster, “Shame on the murderers of the great thinker and militant Hussein Mroueh,” 1987. From the collection of Zeina Maasri. Image from the archive of Signs of Conflict: Political Posters of Lebanon’s Civil War (1975-1990).

Muruwwah returned to Beirut from where he helped launch “the project of our age” (mashru‘ al-‘umr): the Cairo-based al-Thaqafa al-Wataniyya in 1952. This engaged journal gave a programmatic platform to the question of turath, namely, the political force of the Arabo-Islamic heritage for the present.

In one of its first issues –May 1952 – Muruwwah wrote a five-page article, “Ibn Sina: A Progressive Idea.”8 This article referenced the Ibn Sina celebrations in Baghdad “two weeks ago,” and Muruwwah urged his readers to embrace Ibn Sina’s contribution to the “Arabic intellectual heritage …, and as the golden link in the intellectual chain of human civilization in general.” Since the Nahda period of the nineteenth century, Islamic reformers have returned to the heritage of theology and philosophy “by asserting the primacy of the ‘spiritual-moral’ foundations” of Muslim society.9 Muruwwah now warned that this idealist move was based on a static and authenticist conception of the past, and it left unchallenged the material effects of colonialism in the present. Progressives, in particular, ought to study Ibn Sina’s life and work, Muruwwah wrote, not just because he was a polymath, but also because he “combined metaphysics with political engagement and was persecuted for it.” And for all his neo-platonic abstraction, Ibn Sina’s philosophy of nature was materialist. In sum, he was “certainly a living embodiment of a sublime progressive idea called the ‘unity’ of life.”10

Let me turn to our second ‘Aristo-gauchiste.’ Ernst Bloch learnt about the Hamadan celebrations from a Soviet periodical and published his Avicenna and the Aristotelian Left that same year. This professor of philosophy, theologian of revolution, this warm-stream Marxist, and Communist enfant terrible of the Frankfurt School had engaged with Abbasid/Andalusian philosophy for a long time. As early as 1936, he wrote to Max Horkheimer that he had compiled a “materialist reader” for himself of texts by “non-mechanistic materialists … like … [Giordano] Bruno, Ibn Gabirol and Ibn Rushd.” Bloch’s biographer even speculates that the impetus for this interest could have been Bloch’s trip to Tunisia back in 1926.

Both Bloch and Muruwwah returned to Ibn Sina and the materialism debate in their final major works in the 1970s. But before we can get to the content of this debate, I want to ask: What did a materialist reading of Abbasid/ Andalusian philosophy achieve for Bloch and Muruwwah? Why did they bother, as Marxists, to return to the metaphysics of Ibn Sina?

For one, both Bloch and Muruwwah challenged the tunnel visions of their respective communities of discourse in moments of crisis. What was at stake for Muruwwah was finding a method to overcome past mystifications of competing Islamic, nationalist and liberal nostalgias at a time of a deep “crisis of language and life” in the Arab world. What he was searching for in this article and found the answer for in his 1979 masterpiece Materialist Trends in Arabo-Islamic Philosophy, was a method of totality, a method of concrete universals: His answer to the fragmented conceptions of life wrought by capitalism and colonialism was, I argue, a type of Dialectical Materialism grounded in Ibn Sina’s natural philosophy.

There has been a consistent aversion to materialism since Leibniz first coined the term around 1700, to refer to mechanistic interpretations of change around.11 But Bloch found in Ibn Sina the figure of thought to salvage what Stalinist Dialectical Materialism had perverted, and to revive materialist conceptions of Nature and Being as a compound of matter and form (viz. Aristotle’s Hylomorphism).12 It is not mechanical scientific laws of nature that determine human existence, rather Being is open, full of potentiality, it is the result of inchoate dialectical entanglement of consciousness and nature, essence and existence, objectivity and subjectivity, body and soul.

Aristotle-Avicenna-Bloch isnād

To Aristotle, everything that changes must consist of matter. Matter is that out of which natural substances are made – say wood; and form is what the senses perceive – say a tree or a chair. But according to Bloch, Aristotle’s matter merely contains passive possibility, which only finds actualization in form. It was his “friend Ibn Sina”, who offered Bloch a way out, to identify in matter itself metaphysical excess, emancipatory spirit and anticipatory force. Thus, on what Bloch labelled “the Aristotelian Left’s” view, matter is not inert or activated externally, but self-generating. Bloch’s interpretative maneuver is no doubt self-serving. But Bloch’s Avicennan upgrade of Aristotle’s hylomorphism is important nevertheless, not least because one may well derive green Marxism or feminist philosophy from his move.13 This tradition offers a non-anthropocentric form of what Paul Gilroy today calls “planetary humanism,” in which nature and the material world both enable and constrain emancipation.

Genealogy of the “Aristotelian Left”

Bloch brings, somewhat impishly, a hidden ‘peripatetic left’ into being. This tradition leads from late Greek commentators of Aristotle, such as Alexander of Aphrodisias (fl. ca 200), the “protopantheist” who “initiated the concept of the highest potency of matter,” to Avicenna’s “ascendant naturalization,” advanced by the Andalusian-Jewish philosopher Ibn Gabirol (11th century) in the concept of materia naturalis, to Ibn Tufayl’s auto-didactical, philosophical novel Hayy ibn Yaqzan(The Living, Son of the Wakesome), which influenced, via Daniel Defoe’s (d. 1731) Robinson Crusoe, the European enlightenment. Bloch’s isnād culminates, first, with Ibn Rushd who showed matter as eternally in flux and alive in the form of “natura naturans”– self-created nature. For Bloch, Abbasid/Andalusian philosophy presented the first step in the conception of nature as independent from divine fiat and human mastery. And, finally, Giordano Bruno (d. 1600) radicalized matter in the 16th century “as a fructifying and fecund universal life.” Bloch claims that this Aristotelian Left represents a bulwark against “the spirit of otherworldliness”.

The first to take exception to Avicenna‘s main theories—eternal nature of matter, the incorruptibility of the law of causality, the non-resurrection of the dead, and “the subordination of faith in Scripture to cognitive truth—was, of course, al-Ghazali (d. 1111). Following Ibn Rushd’s death, Muslim and Christian scholasticism pilloried the idea that “the active potentiality of matter intermingled with divine potency.” According to Bloch, “Thomas Aquinas by contrast, the world – only ever the creation, never creative – largely withdraws.” After Aquinas, the “Aristotelian Right” considered matter sinful, subordinated it to form, and championed divine authority and feudal-clerical rule.14

Again, Ibn Sina was no natural ally of Bloch’s renewal of materialism project; think of Ibn Sina’s famous floating man, the thought experiment where he claimed that humans had cognition and self-awareness even without somatic perceptions of their environment. Hardly a materialist argument. Nevertheless, Bloch, like Muruwwah, insisted in 1952 that “Avicenna was a doctor and not a monk, a natural philosopher not a theologian.” If in the Axial Age, mythos was transformed into logos, then in the Exegetical Age of Late Antiquity, Ibn Sina “transvalued religious allegories into philosophical concepts.”15 Ibn Sina not only had the world historical distinction of having read Aristotle as a natural philosopher, Bloch later claimed in his The Principle of Hope that “without [Avicenna and the] Aristotle-to-Bruno legacy, Marx would not have been able to upend the Hegelian world idea so naturally.”16

Rediscovering Avicenna and the Aristotelian Left in Arabic

Bloch’s work on Avicenna also furnishes a fruitful approach for studying debates about Orientalism and Islam. Bloch’s recent Arabic translator, Mohamed Turki, believes the book has potential for intercultural dialogue. This makes sense, especially in the context of culturalist tendencies from Huntington to Habermas, but also in certain decoloniality debates that are fashionable these days. But for the moment, I am more interested in two further points that Turki raises in his introduction. First, Turki points out that modern Orientalism perpetuated the marginalization and suppression of the Aristotelian Left tradition. Turki sees Bloch’s book as a subversive act of counter-memory or a genealogical method at work. Bloch claims that Europe owes a debt to “Iranian-Arabic brilliance,” for “it is Ibn Sina, along with Ibn Rushd, who – unlike Western scholars – represent one of the sources of our enlightenment and, above all, of a most singular materialist vitality, developed out of Aristotle in a non-Christian manner.” Bloch was enraged that Max Horten, who translated Avicenna into German in the early 20th century, labeled the anti-Orthodox Averroes as “an apologist for the Koran.”

The second noteworthy point in Turki’s introduction regards the persistence of the Aristotle-Ibn Sina-Ernst Bloch isnādamong the Arab Left in the 20th century. Turki highlights a number of studies including Tayib Tizini’s German doctoral dissertation Mashru‘ ru’ya jadida lil-fikr al-arabi fil-‘asr al-wasīt, as well as the red Mujtahid Muruwwah’s Materialist Tendencies. However, despite elective affinities, neither Tizini nor Muruwwah engage explicitly with Bloch’s work on Avicenna.

Muruwwah, in particular, moved in a somewhat different problem space than Bloch, even though both invoked Ibn Sina after the same communist festivities in 1952. Muruwwah addressed a deep “methodological crisis” which he ascribed to modern Arab thought. According to Muruwwah, Arab historians merely praised the lost classical Arab genius or got lost in isolated textual details. Conversely, modern Arab philosophers and Orientalists had no concept of the socio-economic context of philosophical development. Moreover, the resurgent Salafi discourse of the Anwar Sadat (d. 1981) years denied the central role Aristotle played in Arab/Islamic turath on account of the useful decolonial fiction of the European identity of ancient Greece.

Everything is connected and entangled, Muruwwah claims: past and present, text and context, content and form, epistemology and materiality, as well as the Greek, Arabo-Islamic and European heritage. A properly radical materialist philosophy links these tendencies dialectically. Muruwwah hoped that Arab philosophical engagement with Marx and Engels would offer the much-needed alternative to essentialist theological and abstract juridical conceptions of life, religion and art. But when the almost 80-year-old Muruwwah was assassinated by Islamist militants in the chaos of the Lebanese civil war, it effectively marked the end of the Arab Left.

Conclusion

The 21st century has witnessed a revival of interest in Materialism in general and the works of Muruwwah and Bloch in particular. Ibn Sina and Ibn Rushd have elicited both appreciation and anxiety since the time of al-Ghazali and Aquinas.

For all their heterodoxy, neither Avicenna nor Bloch’s and Muruwwah’s apocryphal Aristotelian Left saw philosophy as antithetical to religion. Avicenna considered philosophy as the path to human self-awareness and to the acceptance of God as necessary existent (wājib al-wujūd), as the all-knowing and first cause of being. Bloch had no time for church fathers and orthodoxy in general, as he saw both in cahoots with political power. Conversely, his metaphysical and theological tendencies made for his pariah status not just in the Soviet Union but also among Western Marxists. His unorthodox and instrumentalist reading of Ibn Sina hardly makes him a serious scholar of Islam. But in the spirit of a sympathetic reading, I credit Bloch with conjuring up a breach the epistemological walls Europeanist systems of philosophy have erected.

Husayn Muruwwah, by contrast, was a very serious scholar of Islam. And on matters of substance, he came to similar conclusions as Bloch. Since his first forays into Ibn Sina in 1952, he continuously worked on the question of method.17 Muruwwah warned that the Abbasid/Andalusian legacy for the present struggle has not really been dealt with properly by contemporary revolutionaries, Arab intellectuals and academics.18

The above is the finest of what ‘Aristo-gauchisme’ has had to offer, if you excuse my impishness. Both Bloch and Muruwwah have offered critiques of the history of philosophy that deserve our serious attention. And they did so not as theoreticians but as philosophers; not as what Habermas labeled idle postmodern theorists, but as creative system builders in their own right. Orthodox Communism may be dead, but we have much to learn from the thought of communist mavericks such as Bloch and Muruwwah in the twilight of liberalism.

My exhortation to the serious study of Bloch’s and Muruwwah’s grounding of European and Islamic philosophy might reek of presentism, too: Should European universities adjust their tried and tested curricula just because of recent demographic changes? Shouldn’t we strengthen, with Habermas, our commitment to Europeanist histories of philosophy? To this rhetorical question my paper provides a tentative two-fold answer: a) the Europeanist version is actually historically inaccurate, as the exclusion of Avicenna et al was ideological, or at least ideological complacency, to begin with; and b) philosophical and cultural traditions intermingled from the very beginning. Arabo-Islamic philosophy was not the absolute other of what became European philosophy in the early modern period. Arguably, Arabo-Islamic philosophy was no less “open to Reason,” to borrow Souleymane Bachir Diagne’s felicitous book title,19 than Aquinas and what Bloch called the Aristotelian Right that have dominated Europeanist philosophy ever since.20

Notes

- Bloch, Ernst [1952], Avicenna und die Aristotelische Linke (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1963); Husayn Muruwwah, Naza‘at al-maddiyya fi al-falsafa al-‘arabiyya al-islamiyya, 4 vols. (Beirut: Dar al-Farabi, 1978). ↑

- Jürgen Habermas, “Ein Gespräch über Gott und die Welt,” in Zeit der Übergänge. Kleine politische Schriften IX (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2001), pp. 173-96. ↑

- Gareth Fowden, Before and After Muhammad: The First Millenium Refocused (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014). ↑

- For more on this see Peter Adamson, Interpreting Avicenna: Critical Essays (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013) and Cristina D’Ancona Costa, “Avicenna and the Liber de Causis: A Contribution to the Dossier,” Revista Española de Filosofía Medieval 7 (2000), pp. 95-114. ↑

- In her thesis, Kara Richardson claims that “Avicenna also holds that the cause of the existence of contingent things is an incorporeal principle, which he describes as an agent who ‘bestows forms.’” I argue that Avicenna fails to resolve the tension between this claim and his commitment to an Aristotelian account of generation; see Kara Richardson, “Avicenna on Teleology: Final Causation and Goodness,” in Teleology, ed. Jeffrey K. McDonough (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020), pp. 71-89. ↑

- Henry Corbin, Avicenne et le récit visionnaire (Téhéran: Société des Monuments Nationaux, 1952-54).. That same year, two previous professors at my university published works on Avicenna: Emil L. Fackenheim, “Ibn Sina: The Man and his Work,” Middle Eastern Affairs 3 (1952), pp. 265-71 and G. M. Wickens (ed.), Avicenna: Scientist & Philosopher: A Millenary Symposium (London: Luzac, 1952). See also Fazlur Rahman (ed.), Avicenna’s Psychology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1952). The Indian Iran society held a congress that year and published its proceedings Avicenna commemoration volume in 1956. ↑

- Louis Allday, “Remembering Husayn Muruwwah, the ‘Red Mujtahid,’” Jadaliyya, 16 February 2017; https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/34028 ↑

- Husayn Muruwwah, “Ibn Sina: A Progressive Idea,” Al-Thaqafa al-Wataniyya, May 1952. Reprinted in his Turathuna, kayfa na‘rifuhu (Beirut: Mu’assasa al-Abhath al-‘Arabiyya, 1985), pp. 31-35. ↑

- Rula Jurdi Abisaab, “Deconstructing the Modular and the Authentic: Husayn Muroeh’s Early Islamic History,“ Critique: Critical Middle Eastern Studies 17 (2008), 239-59. Here: 241. ↑

- Husayn Muruwwah (1952): “…was connected to real practical life, indeed, a strange, intense connection. However, he attained the intensity of his connection to life through his engagement with it. He was completely passionate about it, accepting its pleasures to the degree of gluttony, pursuing its consequences and burdens most ruthlessly, relishing to acquire it, bearing its fate most intensely and strongly.” ↑

- Julia Borcherding, “Reflection, Intelligibility, and Leibniz’s Case Against Materialism,” Logical Analysis and the History of Philosophy 21 (2018): 44-68. ↑

- Bloch’s book on Avicenna and his later summa Das Materialismusproblem were primarily directed against the 19th century controversy about Aristotle’s Hylomorphism (being = compound of matter and form) between physicalists, idealists and sensualists in Hegel’s wake, a debate that expressed a deep identity crisis in German philosophy at the time. Against this background, Bloch’s project for a renewal of materialism on an Avicennan foundation appears pertinent, since for Bloch, the Iranian commemoration of 1952 was significant as an act of actualizing a humanist materialism, as a hope-endowing, salvific practice. ↑

- In fact, Ibn Rushd’s “womb of matter” and Bloch’s idea that matter derives etymologically from mater-mother, may support a feminist critique of Aristotle’s Generation of Animals. This book was, according to Emanuella Bianchi, the foundational text of Western patriarchal metaphysics and sexist notions of heredity. Aristotle identified the female as the source of matter for the offspring, while the male provides the principle of motion, generation and form. Aristotle’s intuition that the masculine operates upon the feminine, the active upon the passive, the semen upon the womb, got him into philosophical trouble explaining female offspring as “material mishaps” or accidents of nature. Bloch’s insistence on the active and procreational potential of matter effectively emasculates the power of form. ↑

- Bloch, Avicenna und die Aristotelische Linke, pp. 11-12, 16. ↑

- Ibid., pp. 15, 23-24. ↑

- Bloch, Ernst [1959], The Principle of Hope, vol. 1 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995), p. 208. ↑

- Muruwwa, Naza‘at al-maddiyya, pp. 23-32. ↑

- Muruwwa, Naza‘at al-maddiyya, pp. 18-19. Either historians worked on isolated historical details, or they produced grand commonplaces about the scientific genius of the Arabs. Representative of this popular approach was the Lebanese historian ‘Umar Farrukh’s ‘Abkariyya al-‘arab fi al-’ilm wa al-falsafa (1945), published as The Arab Genius in Science and Philosophy by the American Council of Learned Societies, Washington, 1954. Arab philosophers, such as ‘Abd al-Rahman Badawi for example, merely offered idealist and metaphysical theories and were oblivious to historical dynamics and socio-economic contexts. ↑

- Souleyman Bachir Diagne, Open to Reason: Muslim Philosophers in Conversation with the Western Tradition (New York: Columbia University Press, 2018). ↑

- Bloch, Avicenna und die Aristotelische Linke, pp. 46-7. ↑