PDF

Download

Citations

Click and drag then release to select a passage to cite.

Annotations

How to submit annotations to Mizan Journal articles:

your work is published.

Search within

A Migrating Motif

Abraham and his Adversaries in Jubilees and al-Kisāʾī

Image

Audio

Video

Chart or Graph

A Migrating Motif

Abraham and his Adversaries in Jubilees and al-Kisāʾī

Introduction

Comparisons are often made between haggadic literature and Islamic stories found in the ḥadīth and qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ.1 Given that at times narratives expand and characters are fleshed out in a similar fashion, it is difficult to avoid making such comparisons and discussing the relationship between Jewish and Islamic sources.2 Efforts to forge a relationship—in whichever way this relationship is conceived—between Jewish and Muslim extra-scriptural narrative expansions have mainly focused on rabbinic material found in midrashic corpora and the Talmuds.

The relationship between early Jewish pseudepigraphic works and late rabbinic and early medieval literature continues to captivate scholarly attention, and for good reason. How does one account for the appearance of the literary building blocks of Second Temple literature in later Jewish and Christian sources? For example, how did the author of Pirqei de-Rabbi Eliezer have access to pseudepigraphic works? Or perhaps we should ask, did the author have access to pseudepigraphic works? If so, in what language were they transmitted? Hebrew or Aramaic? Greek or Latin? Were they transmitted by way of Semitic translations of later recensions? As John Reeves asks, did works like 1 Enoch, Jubilees, and the Testament of Levi

re-enter Jewish intellectual life after a long hiatus, due to a fortuitous manuscript discovery or a simple borrowing of intriguing material from neighboring religious communities? Is it possible to trace a continuous ‘paper trail’ leading from Second Temple scribal circles down to the learned haggadists and interpreters of medieval Judaism?3

Moreover, can such evidence possibly lead to Islamic circles?4

In light of the dissemination of Jewish pseudepigraphic works in the medieval period, we should consider more capacious comparisons that include pre- and para-rabbinic material. As a gesture toward the endeavor to explore how Second Temple literature echoes in medieval works, what follows is a preliminary literary analysis that compares the role the birds trope plays in the story of Abraham and his adversaries in Jubilees, a second-century BCE work that purports to be God’s revelation to Moses on Mount Sinai, and in Muḥammad b. ʿAbd Allāh al-Kisāʾī’s Tales of the Prophets. I hope my broader examination of the story of Abraham’s encounter with an adversary, Mastema in Jubilees and Nimrod in Kisāʾī, will serve as a case study for interrogating the ways in which literary elements migrated across geographic and temporal lines, and the role they play in shaping the reception of scriptural narratives. The purpose here is not to locate a point of origination, but rather to detect resonances between Jewish and Islamic narratives over a broad span of time.

We will first assess the ways in which Abraham’s arch-nemesis Nimrod functions as an anti-hero similar to the angel Mastema in Jubilees. We will then turn to two episodes involving Abraham and birds and examine their respective roles within each narrative arc. In Jubilees, whole birds are sent away and scattered; in Kisāʾī, severed, scattered pieces of birds are made whole. In both instances, however, the story functions to give expression to Abraham’s power over a malevolent figure who challenges God’s omnipotence. Both bird episodes, moreover, function to interpret a scriptural verse.

This analysis of how each episode functions in stories about Abraham’s battle against an enemy will not demonstrate a direct relationship between these works—although that is not entirely inconceivable. Rather, it will highlight the literary parallels and distinctions that might, even modestly, contribute to our assessment of the qiṣaṣ genre with respect to its theological framework and worldview, as well as its relationship to other forms of scriptural expansion.

The qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ genre

The Islamic tales of the prophets (qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ) are stories about the lives of the prophets of the Qurʾān. They flesh out the qurʾānic narrative with all kinds of fascinating and fantastical details about the prophets’ character traits and episodes in their lives. Many of the motifs and tropes employed in these accounts are also found in Christian and Jewish literature; some even date back to antiquity. Like other para-scriptural texts, these stories help shape one’s knowledge and impression of figures such as Adam, Noah, Abraham, Ishmael, Isaac, Moses, and Jesus, so much so that often our common understanding of the prophets, as well as other characters in the prophets’ narratives (for example Sarah, Mary, or Iblis), is actually a conflation of details gleaned from the Qurʾān itself and extra-scriptural sources such as the tales.

Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ also refers to a genre of literature and not just to a specific qiṣṣah (story). Furthermore, while one finds these stories in qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ collections, the stories appear in other genres of literature such as tafsīr (qurʾānic exegesis) and taʾrīkh (historiography). The different renditions disseminated widely across genres attest to their popularity and function in fleshing out the Islamic metanarrative and fostering theological and moral teachings of the Qurʾān. To be sure, some plots, characterizations, tropes, and motifs may have been in widespread circulation centuries before the composition of the Qurʾān, and were quite familiar to Jews and Christians. The manner in which elements of these stories were synthesized is therefore all the more important for understanding the role these stories played in the Islamic tradition of the medieval period, and how they relate to similar stories in Jewish and Christian literary traditions.

Narrative embellishments and adaptations are part and parcel of how stories maintain their cultural purchase and staying power throughout the centuries. This is certainly the case when taking into account the vast literary circulatory system of the Near East that includes not only accounts of biblical and qurʾānic heroes, but also their antagonists. Advances in the study of ancient Judaism, as well as early Christian and Islamic literature, have clearly demonstrated the ways in which stories in written and oral form migrated throughout the Near East. In the process, they were expanded and embellished to suit the desires and needs of those transmitting tales for purposes of edification and entertainment.

Narrators (quṣṣāṣ; sing. qāṣṣ) were respected figures in early Islamic society, serving not only to recite the Qurʾān, but also to expound it in an effort to stir the piety of listeners and impart moral lessons. While the story-tellers garnered esteem and respect during the early Islamic period, over time the liberties they took and excessive embellishments they made tarnished their reputations. Yet despite their marginalization, even today within the realm of popular culture, the stories themselves continue to ignite the imagination and interest of readers.5

The collection of tales of Kisāʾī stands out as one of the most popular medieval collections.6 It narrates the adventures and miraculous works of the prophets, and in some instances their escape from imminent danger as well as their victorious battles against the forces of evil. Such is the case of the episode of Abraham’s encounters with Nimrod (Namrūd). The story takes qurʾānic episodes about Abraham’s clashes with non-believers and relates his powerful victory over Nimrod.

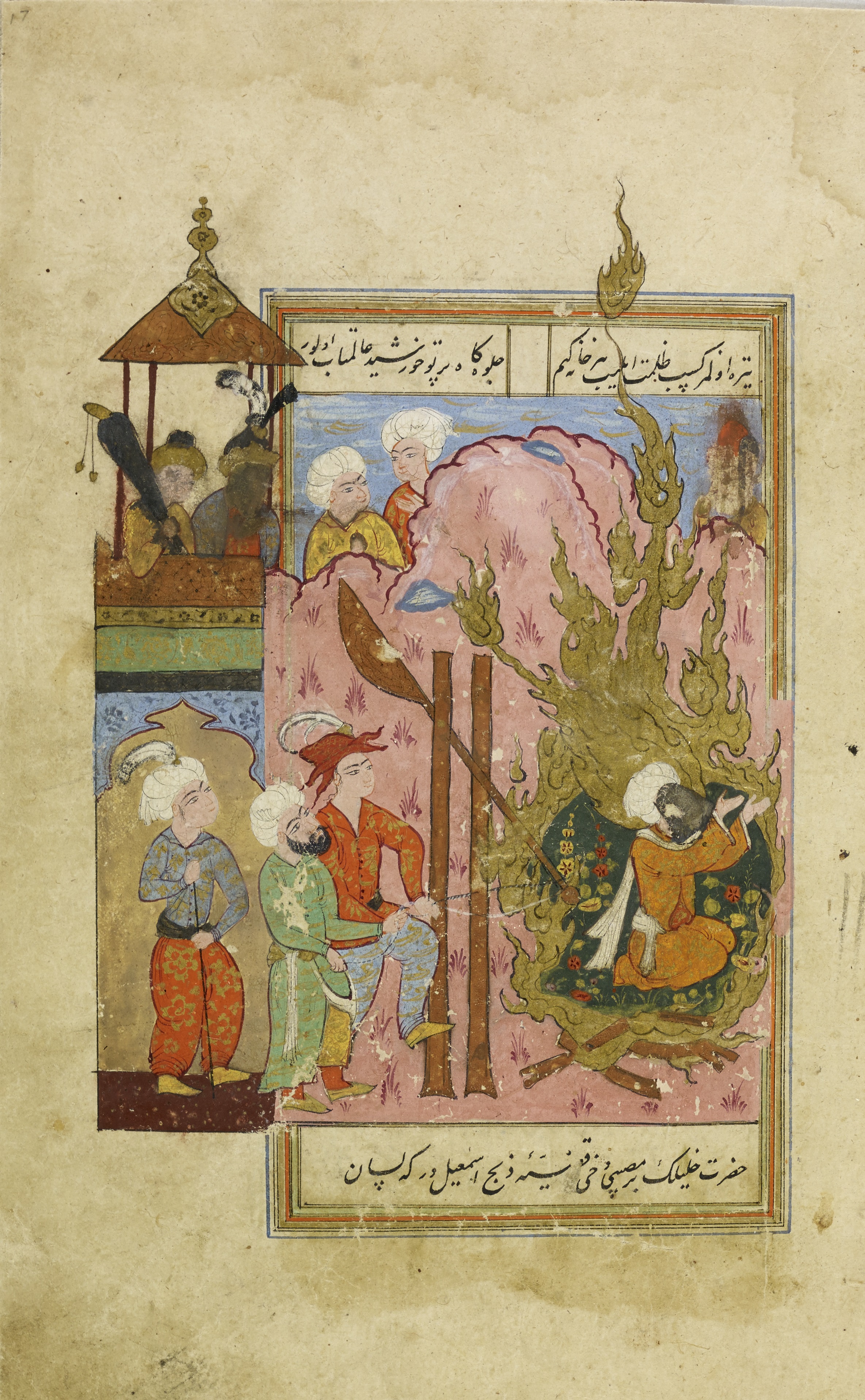

In the Qurʾān, Abraham has to contend with the idol worshippers around him who cast him into the fire (see Gallery Image A), but he lacks a specific antagonist.7 Adam is challenged by Satan, and Moses by Pharaoh, but Abraham has no evil counterpart mentioned by name. In Sūrat al-Baqarah, however, reference is made to an arrogant, blaspheming ruler who confronts Abraham and contends that he, not God, has power over life and death:

[Prophet,] have you not considered the one who argued with Abraham about his Lord, because God had given him kingship? When Abraham said, “My Lord is the one who gives life and death,” he said, “I give life and death.” Abraham said, “Indeed, God brings up the sun from the east, so bring it up from the west.” The disbeliever was stupefied. God does not guide the wrongdoers. (Q Baqarah 2:258)8

Who is the leader who claims to be equal to Abraham’s Lord? Although the Qurʾān does not identify him, extra-qurʾānic tales and exegetical traditions not only give him a name—Nimrod—but also recount his wickedness in horrifying detail.

Abraham, Mastema, and the birds in Jubilees

The name of Mastema, a personification of evil, means “loathing,” “hating,” and most probably is derived from the Hebrew verbal root s-ṭ-m, meaning “to despise, to harbor hostility, enmity.”9 He is the chief angel of loathing, sar mastema, accorded a higher status than the other spirits. Mastema, referred to as Satan in Jubilees 10:11, leads the forces of evil in the world, and, like Satan in Job, negotiates with God.

Mastema plays a central role in Jubilees, in a work that, through its retelling of the story of Genesis and Exodus, focuses on the restoration of Israel. At every turn, his attempts to test faith in God, that is, to take Israel off its course toward restoration, are met with defeat. Whether tempting Abraham to disobey God’s command to sacrifice Isaac or conniving during the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt, Mastema is God’s nemesis. He tempts humans to commit idolatry (Jub. 11:4–6), prompts God to command Abraham to sacrifice Isaac (17:16), and, on Moses’ way down to Egypt, he threatens Moses’s life (48:9–10 and 12). In short, on the playing field where good and evil battle for human souls, Mastema, the ruler of the evil realm, is God’s quintessential archenemy.10

Let us look at a specific example that we will revisit when we examine Nimrod’s encounters with Abraham in Kisāʾī. Just after the birth of Abraham’s father, Terah, Mastema sends ravens to devour all the seed before it could be plowed:

Then Prince Mastema sent ravens and birds to eat the seed which would be planted in the ground and to destroy the land in order to rob mankind of their labors. Before they plowed in the seed, the ravens would pick (it) from the surface of the ground… The years began to be unfruitful due to the birds. They would eat all the fruit of the trees from the orchards. (Jub. 11:11–13)

The story continues with the announcement of Abraham’s birth and his awareness of the idolatry around him:

The child began to realize the errors of the earth—that everyone was going astray after the statues and after impurity. His father taught him the art of writing. When he was two weeks of years [i.e., fourteen years old], he separated himself from his father in order not to worship idols with him. He began to pray to the creator of all that it might not fall to his share to go astray after impurity and wickedness” (Jub. 16-17).

Abraham would go out with everyone during the sowing season “to guard the seed from the ravens… ”

As a cloud of ravens came to eat the seed, Abram would run at them before they could settle on the ground. He would shout at them… and would say: “Do not come down; return to the place from which you came!” And they returned. That day he did (this) to the cloud of ravens seventy times. Not a single raven remained in any of the fields where Abram was. All who were with him in any of the fields would see him shouting: then all of the ravens returned (to their place). His reputation grew large throughout the entire land of the Chaldaeans. All who were planting seed came to him in this year, and he kept going with them until the seedtime came to an end. (Jub. 11:19–21)11

Even though there is no mention of Gen 15:11, it seems that the story embellishes this verse: “When the birds of prey descended upon the pieces, Abram drove them away.” In this chapter of Genesis, in a formalized ceremony, God affirms his promise to Abraham of land, nation, and blessing (cf. Genesis 12). He commands Abram (his name at the time) to do the following: “Bring Me a three-year-old heifer, a three-year-old she-goat, a three-year-old ram, a turtledove, and a young bird” (Gen 15:9). When Abram brought them, he cut them in half, placing them opposite each other, but he did not “cut up the bird” (Gen 15:10). It is at this moment that “birds of prey descended upon the pieces, Abram drove them away” (Gen 15:11).

Jubilees introduces Abraham (Abram) as pious and unlike the people around him. He proves himself a leader and saves the people from famine. His fame was known throughout the land of the Chaldaeans. Abraham prays to the creator of all and in a sense is rewarded by being endowed with the power to ward off the birds. Mastema poses a challenge that Abraham, who turns to God, is able to overcome. As we will see shortly, there are parallels, despite obvious differences, between this episode in Abraham’s life as depicted in Jubilees and that in Kisāʾī.

Classical rabbinic literature says very little if anything about Genesis 15:11. Genesis Rabbah 44.16, for example, mentions that Abraham drove the birds of prey away, and generations of Jews to follow will merit from Abraham’s pious act. The rabbis do not interpret the verse as one of the trials Abraham faces.12 However, the passage in Jubilees elaborates upon the biblical narrative and amplifies Abraham’s prowess in warding off the birds, not only once, but seventy times in one day! Although it is not listed in the seven trials Abraham faces listed in Jubilees (Jub. 17:17–18), by thwarting Mastema, Abraham nonetheless displays his obedience and worthiness to cut a covenant with God.13

In later Jewish traditions there is no parallel to this passage in Jubilees, but as Sebastian Brock demonstrates, it has a curious variant that is preserved in Syriac sources (viz., the Catena Severi and the letter of James of Edessa to John of Litarba)14 Brock argues that the schema of the Syriac form of the tradition is, in fact, anterior to the basis of the pattern in Jubilees, and in Jubilees it serves to introduce Abraham as the inventor of the plow. Whereas in the Syriac texts the ravens are sent by God as punishment for idolatry, in Jubilees they are sent by Mastema. Like the Aqedah (the “binding of Isaac”) in Jubilees, which is initiated not by God but by Mastema, here too Mastema functions as a foil. The birds episode is presented as Mastema’s opposition to God which Abraham meets successfully.15

Jubilees depicts a world in which, as Segal describes it, “heavenly forces and earthly nations are divided in a seemingly dualistic system… the evil divine powers rule over the wicked people, while the good forces govern the righteous.”16 Abraham is portrayed as one who disavows idolatry, turns to God, and fights against Mastema, the leader of the forces of evil. Genesis 15:11 may be the scriptural occasion for this narrative amplification, although reference to the covenantal ritual is explicitly lacking. Be that as it may, the story in Jubilees depicts Abraham as heroically foiling Mastema’s attempt to disrupt the agrarian cycle, threaten humanity, and challenge God’s authority. The birds episode functions as a trope for Abraham’s power as well as piety.

Nimrod in Second Temple and rabbinic sources

In the book of Genesis, Nimrod is the son of Cush, and is a mighty hunter. Whereas the Bible tells us hardly anything about Nimrod, post-biblical traditions amplify and develop his character. Pieter Van der Horst maintains that Philo of Alexandria is the earliest post-biblical writer who connects the gibborim, the offspring of the sons of God who mate with humans in Genesis 6:4, to Nimrod, who is called a gibbor (one who is powerful) in Genesis 10:8–9.17 According to Philo’s commentary on Genesis 6:4 (On Giants, 65–66), Nimrod is an example of the sons of the earth who succumb to the nature of the flesh instead of being governed by reason. He writes: “For the lawgiver says, ‘he began to be a giant on the earth’ (Gen 10:8), and his name means desertion.” Philo, moreover, provides an etymology for his name: “desertion.” We find this notion in other traditions that explain his name from the Hebrew marad, “to rebel” against God, and in this sense we detect Philo’s notion of Nimrod as one who deserts God.

Perhaps the earliest attestation of Abraham’s encounter with Nimrod is found in Pseudo-Philo’s Biblical Antiquities, a work dated to the second half of the first century CE. Chapter 5 of this work opens with the statement that the sons of Ham made Nimrod their leader, and chapter 6 develops the story between Abraham and Nimrod. The leaders of the tribes of Shem, Ham, and Japheth plan to build a tower in Babel; however, twelve men refuse to participate out of devotion to the Lord. Abraham, one of the twelve, is locked up with the others, and is then cast into a fire.18 As van der Horst notes, we cannot be certain whether Pseudo-Philo is the originator of the fire motif, nor can we claim that the confrontation between Abraham and Nimrod was widespread at the time since it is absent in Josephus.19

Rabbinic traditions associate Nimrod with Amraphel, a king mentioned in Genesis 14, and depict him as leading a worldwide rebellion against God, and as ordering that Abraham be thrown into a fiery furnace. In Genesis Rabbah 42:4, Amraphel is known also as Nimrod because he incited the world to rebel (himrid, a play on his name, nimrod). According to the Babylonian Talmud (b. Pesaḥim 94b), Nebuchadnezzar is a descendant of Nimrod.20 Elsewhere in the Talmud (b. Ḥagigah 53b) he is associated with the Tower of Babel (or “Temple of Nimrod”),21 and other rabbinic sources refer to Nimrod casting Abraham into the fire.22 Leviticus Rabbah 27:5 and Ecclesiastes Rabbah 3:18 mention that Nimrod pursued Abraham. Deuteronomy Rabbah 2:27 refers to Abraham’s encounter with Amraphel, his arrest, and his trial by fire.23

Throughout the medieval period, Nimrod was depicted as a giant who built the tower of Babel, and his image as God’s archenemy grew in Jewish, Christian, and Islamic circles. Van der Horst writes:

Haggada in which Nimrod is mentioned explicitly is found for the first time in the first century CE. But since we know from Jubilees, from Pseudo-Eupolemus, and from Philo the epic poet, that already in the second century BCE there was Abraham haggada in which a connection had been made between Abraham and the giants, and between the tower of Babel and Abraham, it is hardly thinkable that the Nimrod connection was made only two centuries later.24

He continues by considering that one of the earliest factors that contributed to this process was “the circumstance that the biblical text called Nimrod a gibbor/gigas, using the same word as in Gen 6:4 for the offspring of the rebelling sons of God.”25

I would also suggest the possibility that the more fully developed Nimrod resonates with Mastema, who asks God (Jub. 10:8–9) to leave under his domain some of the giants, that is, the Nephilim of Genesis 6:4. While one is hard pressed to regard Mastema as a prototype, one cannot ignore factors that evoke comparison, namely that both are leaders of wicked forces that clash against Abraham in a series of challenges, one of which involves birds. The figure of Nimrod as portrayed in Kisāʾī’s Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ helps us to draw that comparison.

Abraham, Nimrod, and the birds in the tales of the prophets

In Islamic literature, Nimrod and Pharoah symbolize the boastful, arrogant ruler.26 In Kisāʾī’s Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, Nimrod is a tyrant, a giant (jabbār in Arabic). He is the unrelenting force of evil that keeps humanity from righteousness. He builds a palace, slays the first-born male, and dies after a gnat enters his brain and gnaws at it for four hundred years. That he dies from a gnat entering his nostril and gnawing on his brain is found in many Islamic tales about him, and parallels the well-known story of the demise of Titus in rabbinic sources.27

Islamic collections of the tales of the prophets do not all include the same stories, and renditions differ from collection to collection despite common threads. For example, the depictions of Nimrod of Abū Isḥāq Aḥmad b. Muḥammad b. Ibrāhīm al-Thaʿlabī (d. 427/1035) and Abū Jaʿfar Muḥammad b. Jarīr al-Ṭabarī (d. 310/923) include tales of the building of the tower of Babel not found in Kisāʾī, but as noted earlier, Nimrod is identified in rabbinic sources with the tower .28 Kisāʾī’s characterization of Nimrod, however, is rather elaborate, and his rendition of Nimrod’s battle against Abraham is one of the most captivating tales among the collections.29 His Nimrod takes on a similar function as Mastema in Jubilees—the primary force of evil that relentlessly attempts to keep humanity from righteousness. One specific element of the story as Kisāʾī frames it resonates with Mastema’s attempts to wage war against God: the episode of Abraham with birds. Indeed, while in rabbinic literature Nimrod is portrayed in opposition to God, the appearance of the episode of Abraham and the birds within Kisāʾī’s larger Nimrod account actually parallels that of the narrative of Mastema thwarting God and Abraham vanquishing his enemy in Jubilees.

To be sure, unlike Mastema who is an angel, a leader of wicked spirits, Kisāʾī depicts Nimrod as human, although one born accursed. When his mother delivered him at birth, “a thin serpent came out of her womb and entered the boy’s nose.” When she took him into the wilderness to a shepherd to raise him, even the cattle would not go near the boy. The “black, flat-nosed boy” was suckled by a tigress.30 When he grew up, he became a highway robber, plundered towns and cities, stole from people, and took women captive.31 Iblis (Satan) teaches him the sciences of sorcery and soothsaying. He deems himself the creator of all and expects humans to worship him. He distributes food to his subjects, dismissing, however, without supply those who refuse to confess his supremacy over the God of Abraham.

Kisāʾī’s story of Abraham and Nimrod is relatively long and elaborate. Nimrod asks Abraham to follow his religion and worship him, but Abraham refuses, thus setting off a series of contests between Nimrod and Abraham. The story expands upon the qurʾānic passage in Surat al-Baqarah:

[Prophet,] have you not considered the one who argued with Abraham about his Lord, because God had given him kingship? When Abraham said, “My Lord is the one who gives life and death,” he said, “I give life and death.” Abraham said, “Indeed God brings up the sun from the east, so bring it up from the west.” The disbeliever was stupefied. God does not guide the wrongdoers. Or take the one who passed by a ruined town. He said, “How will God give this [town] life when it has died?”… And when Abraham said, “My Lord, show me how You give life to the dead,” He said, “Do you not believe, then?” “Yes,” said Abraham, “but just to put my heart at rest.” So God said, “Take four birds and train them to come back to you. Then place them on separate hilltops, call them back, and they will immediately come back to you; know that God is all powerful and wise.” (Q 2:258–260)

The Qurʾān identifies neither the disbeliever nor the passerby. Moreover, there is no context given for Abraham’s request to God for an explanation of the resurrection.

In Kisāʾī, the qurʾānic passage is contextualized within the broader battle between Nimrod and Abraham. Nimrod boldly asserts that his kingdom is greater than God’s; a debate as to who has greater power ensues. Nimrod’s competition for sovereignty even extends to the non-human realm. A beautiful cow proclaims, “Enemy of God, were I given leave by my Lord, I would gore you so that afterwards you would never be able to eat again!”32 He kills the cow but God restores it to life.

The story continues: “Abraham turned and saw a slave-girl in the palace. She was nursing Nimrod’s small daughter. Suddenly the girl leapt from her mother’s lap, faced Nimrod and said, ‘Father, this is God’s prophet Abraham.’ And Nimrod ordered her cut to pieces.”33 This is in contrast to God who resurrects the dead, which is mentioned several times in Abraham’s encounters with Nimrod, but also throughout the work as a whole. Within this battle of words and deeds we read:

[Abraham said:] “Verily God is not incapable of anything; he is capable of all things.” “What do you know of His power?” asked Nimrod. “My Lord is the one who giveth life, and killeth,” (Q 2:258) said Abraham. “I give life, and kill,” said Nimrod. “How can you do that?” asked Abraham. “I set free from prison men sentenced to death, and I kill men not sentenced to die.” “My Lord does not give life or cause death thus,” said Abraham. “He quickens the dead and He causes death to the living yet kills them not. But, O Nimrod, god bringeth the sun from the east, now do thou bring it from the west.” Whereupon Nimrod was confounded. Then Abraham called upon his Lord and said, “O Lord, show me how thou wilt raise the dead” (Q 2:260).

Kisāʾī adds colorful detail to God’s commands to Abraham to take four birds and bring them back to him:

Abraham took a white cock, a black raven, a green dove, and a peacock, killed them, cut off their heads, mixed up the blood and feathers, and scattered their flesh on four mountain tops. He then called them, and the heads went out of his hands, each returned to its own body, saying, “There is no god but God; Abraham is God’s apostle to Nimrod and his people.”34

The qurʾānic verses are here given a context, namely the contest between Nimrod and Abraham. The cut-up birds coming back to life, in the context of Abraham’s ordeal, is reminiscent of Abraham ordering the ravens in Jubilees to return to the place from which they came after Mastema sent them to eat the seed.35 In that account, Abraham develops such a reputation for his ability to ward off the birds that everyone planting seed would seek his assistance. Abraham is victorious over both Mastema and Nimrod.

In both instances, Abraham demonstrates the power of God over evil. The story of the birds appears in the context of Mastema’s attempts to defy and defeat God by starving humans, thus bringing about their demise, whereas in Kisāʾī’s Tales of the Prophets, the story of the birds serves as evidence of the all-powerful God who gives life and brings the dead to life. It is one more victory in Abraham’s campaign against Nimrod, and idolatry in general. Despite the differences not only in the stories, but also in what happens to the birds in each narrative, the motif of Abraham and the birds plays a similar function in both stories of his victory over evil.

Kisāʾī’s Nimrod is a full-blown nemesis, who unremittingly wages war against Abraham’s God, whereas in Thaʿlabī’s text, by contrast, Nimrod recognizes God’s greatness. There, after Abraham succeeds in walking through the fire into which he was cast, Nimrod announces his desire to sacrifice four thousand cows to God. Abraham tells him that God will not accept his offering unless he abandons his religion, which Nimrod claims he cannot do. He nonetheless slaughters the cattle, forbids anyone to harm Abraham, and proclaims, “How excellent is the Lord, your Lord, Abraham.”36 It is true that in this collection of tales, Nimrod suffers for the entire period of his rule—four hundred years—from the gnawing gnat in his brain. The inclusion of this proclamation of the excellence of the Lord of Abraham, however, attenuates the depiction of Nimrod as the archvillain of God that we find in Kisāʾī. Similarly, in Ṭabarī’s History, Nimrod acknowledges the greatness of Abraham’s God.

The qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ in general provide ample details that embellish Nimrod’s role as God’s archrival. Nimrod was Abraham’s contemporary, and pretended to have the power to give and take life. Nimrod claims to have created humans and given them sustenance. There is no doubt that Kisāʾī had many stories about Abraham and his battles against idolatry at his disposal, as well as depictions of Nimrod. The contextualization of Abraham’s restoration of the cut birds within his battle with Nimrod echoes, albeit rather faintly, the use of the birds in Jubilees to demonstrate Abraham’s piety. Abraham and Mastema and Abraham and Nimrod battle against each other in the cosmic war between God and the forces of evil.

Conclusion

Rabbinic literature is often the starting point for those interested in locating intertexts and establishing relationships between Jewish and Islamic literature, but rabbinic depictions of characters are rarely if ever so colorful. Moreover, a world that is divided into good and evil, angels and demons, and God and his opponents is rather foreign to the rabbinic literature. To be sure, there are indeed rebellious, evil-intentioned figures who defy God, but this dualism that we find in the Qurʾān and Jubilees as well as apocalyptic literature is not characteristic of rabbinic literature in general.37 The literary framing of Jubilees, as well as its Weltanschauung, resonates in the tales of the prophets generally and in Kisāʾī’s Qiṣaṣ specifically, so much so that it is worthwhile to compare these antagonists in Jubilees and Kisāʾī, as opposed to comparing Kisāʾī’s Nimrod to the portrayal found in haggadic texts. However, our comparison is not just between Mastema and Nimrod, but between the role the birds incident plays in each.

This raises an exceedingly complicated question: to what extent was Jubilees “present” in medieval Jewish, Christian, and Muslim circles? The extent to which and the means by which stories in Jubilees were familiar to early medieval audiences are matters that continue to occupy the attention of scholars of medieval Jewish, Christian, and Muslim literature.

In her “Sipurei ha-Nevi’im ba-Masoret ha-Muslemit” (“Stories of the Prophets in the Muslim Tradition”), Aviva Schussman maintains that there are similarities between Kisāʾī’s Tales and Pirqei de-Rabbi Eliezer (PRE).38 It is debated among scholars whether the author of PRE was familiar with Jubilees, but for our purposes we might say that both works, Kisāʾī’s Tales and PRE, seem to be familiar with the themes and traditions of Jubilees. After all, PRE is a product of the early Islamic milieu and issues from the same cultural environment as the earliest qiṣaṣ traditions.39 This is suggestive and requires further investigation; however, it does point to the possibility that Jubilees traditions were disseminated in the medieval period, namely in the early Islamic milieu.

Moreover, in his article “The ‘Prince Mastema’ in a Karaite Work,” Yoram Erder examines a Karaite commentary, that of Yefet ben Eli, on Exod. 32:4, in which Yefet claims that the Sadducees believed in a figure he calls Prince Mastema.40 Erder suggests that the Karaites could have learned about this figure from such works as Jubilees.41 This is not to claim that al- Kisāʾī had Jubilees at his disposal, but rather to raise an awareness of the possibility that Mastema was more popular in medieval literature than our classic rabbinic texts suggest and that this personification of evil was refashioned in the fanciful tales of the Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, in particular that of Kisāʾī.

The connections between Jubilees and Islamic literature have yet to be fully explored. Although details of a complex network of Near Eastern stories, maxims, prayers, inter alia, remain sketchy, a comparison of the figures of Mastema and Nimrod affords us an opportunity to appreciate the centrality of the role of arch villain in Jubilees and Kisāʾī’s Tales of the Prophets. The differences between Mastema and Nimrod are stark, even as both function as similar foils in the retelling of the victory of God’s righteous servant Abraham over the forces of evil. What is noteworthy is how the episode with Abraham and the birds is embedded into this larger narrative.

Again, this is not to suggest that al- Kisāʾī was directly familiar with Jubilees, nor that the only model for Kisāʾī’s Nimrod is Mastema. In light of broader considerations of the transmission of tropes, motifs and traditions across geographic, religious, and temporal lines, an examination of the depiction of the episode of Abraham and the birds within the context of the broader battle between God and an evil force calls attention to how aspects of Second Temple literature reverberate many centuries later, even if only faintly. While we do not want to draw a straight line between Mastema and Nimrod, Kisāʾī’s portrayal of Nimrod does present us with an opportunity to recognize how compatible literary elements and images combined over time to tell the story of Abraham’s victory over the forces of evil.

Appendix

For a general discussion of the relationship between Jewish and Muslim exegetical sources, see Michael E. Pregill, “The Hebrew Bible and the Quran: The Problem of the Jewish ‘Influence’ on Islam,” Religion Compass 1 (2007): 643–659; Carol Bakhos, The Family of Abraham: Jewish, Christian and Muslim Interpretations (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014), 22–25; and Shari L. Lowin, The Making of a Forefather: Abraham in Islamic and Jewish Exegetical Narratives (Leiden: Brill, 2006), 33–38. In “Some Explorations of the Intertwining of Bible and Qur’ān,” in John C. Reeves (ed.), Bible and Qur’ān: Essays in Scriptural Intertextuality (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature Press, 2003), 43–60, Reeves argues that reading the Qurʾān along with other Muslim literature can throw interpretive light on the Bible and its reception in such works as Jewish pseudepigrapha and midrash.

Reuven Firestone, Journeys in Holy Lands: The Evolution of the Abraham-Ishmael Legends in Islamic Exegesis (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), explores the relationship between Jewish interpretations of the Bible and Muslim exegesis of the Qurʾān in his focused study of Abraham-Ishmael traditions. Also, Jacob Lassner, Demonizing the Queen of Sheba: Boundaries of Gender and Culture in Postbiblical Judaism and Medieval Islam (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), looks at the Queen of Sheba accounts from what he terms the “Islamicizing” of Jewish cultural artifacts. For Lassner, Muslim allusions to the Bible are understood as purposeful and the absorption and transmission of Jewish artifacts intentional. He also locates the use of Jewish sources within a polemical context of the Jews’ rejection of the Prophet Muḥammad in Medina. For a discussion of their work, see Brannon M. Wheeler, Moses in the Quran and Islamic Exegesis (London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2002), 3–6.

Indeed, scholarship of recent decades rejects the notion of “borrowing” in favor of a more complex notion of intertextuality; not only does it attribute intentionality to the absorption of late antique Jewish, Christian, and Greco-Roman sources, but it also recognizes the symbiotic relationship of self-definition between Jews and Christians, Christians and Muslims, and Muslims and Jews. An excellent example of cross-cultural intertextuality is evidenced in a Judeo-Arabic retelling of the story of Joseph titled The Story of Our Master Joseph the Righteous, which interweaves elements from both Jewish and Islamic cultures. For a detailed analysis, see Marc. S. Bernstein, Stories of Joseph: Narrative Migrations between Judaism and Islam (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2006).

See also Steven Wasserstrom, Between Muslim and Jew: The Problem of Symbiosis under Early Islam (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995). Focusing on the period from the eighth through the tenth centuries, Wasserstrom analyzes the concept of creative symbiosis by looking at the Judeo-Isma’ili interchange and the ways in which Jews and Muslims shared the imaginative world of apocalypse, as well as the intellectual world of philosophy. In the same vein as Hava Lazarus-Yafeh, “Judaism and Islam: Some Aspects of Mutual Cultural Influences,” in her Some Aspects of Islam (Leiden: Brill, 1981), 72–89, passim, Wasserstrom notes, “I would emphasize that the debtor-creditor model of influence and borrowing must be abandoned in favor of the dialectical analysis of intercivilizational and interreligious process” (11).

About the author

Carol Bakhos is Professor of Judaism and the Study of Religion at UCLA. Since 2012 she has served as Chair of the Study of Religion program and Director of the Center for the Study of Religion at UCLA. Her Islam and Its Past, co-edited with Michael Cook, was published this summer (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017). Her most recent monograph, The Family of Abraham: Jewish, Christian and Muslim Interpretations (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014), was recently translated into Turkish. Her other works include Ishmael on the Border: Rabbinic Portrayals of the First Arab (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2006), winner of a Koret Foundation Award; Judaism in its Hellenistic Context (Leiden: Brill, 2004): the edited volume Current Trends in the Study of Midrash (Leiden: Brill, 2006); and the co-edited work The Talmud in its Iranian Context (Heidelberg: Mohr Siebeck, 2010). Bakhos is co-editor of the AJS Review.

Notes

1 This is a significantly revised, more fully developed version of my article “Transmitting Early Jewish Literature: The Case of Jubilees in Medieval Jewish and Islamic Sources,” in Christine Hayes, Tzvi Novick, and Michal Bar-Asher Siegal (eds.), The Faces of Torah: Studies in the Texts and Contexts of Ancient Judaism in Honor of Steven Fraade (Journal of Ancient Judaism Supplements 22; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, 2017). I want to thank the anonymous readers for helpful comments.

2 For references to scholarship on the relationship between Jewish and Muslim exegetical sources, see the Appendix.

3 John C. Reeves, “Exploring the Afterlife of Jewish Pseudepigrapha in Medieval Near Eastern Religious Traditions: Some Initial Soundings,” Journal for the Study of Judaism in the Persian, Hellenistic and Roman Period 30 (1999): 148–177, 148–149. For discussions of the development and transmission of Second Temple literature and medieval Jewish sources, see Fred Astren, “The Dead Sea Scrolls and Medieval Jewish Studies: Methods and Problems,” Dead Sea Discoveries 8 (2001): 105–123; Martha Himmelfarb, “R. Moses the Preacher and the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs,” AJS Review 9 (1984): 55–78; eadem, “Some Echoes of Jubilees in Medieval Hebrew Literature,” in John C. Reeves (ed.), Tracing the Threads: Studies in the Vitality of Jewish Pseudepigrapha (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1994), 115–141; and eadem, Between Temple and Torah: Essays on Priests, Scribes and Visionaries in the Second Temple Period and Beyond (Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism 151; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2013), and more recently, Martha Himmelfarb, “Medieval Jewish Knowledge of Second Temple Texts and Traditions,” [forthcoming] and Rachel Adelman, The Return of the Repressed: Pirqe de-Rabbi Eliezer and the Pseudepigrapha (Leiden: Brill, 2009). For a good examination of how Christian writers served as facilitators for the transmission of earlier Jewish sources, see Annette Yoshiko Reed, “From Asael and Šemiḥazah to Uzzah, Azzah, and Azael: 3 Enoch 5 (par. 7–8) and Jewish Reception-History of 1 Enoch,” Jewish Studies Quarterly 8 (2001): 105–136, who argues that the Semihazah and Azael tradition may have made its way into later Jewish exegetical traditions via Christian chronographers.

4 In his essay, “Islam and the Qumran Sect,” Chaim Rabin argues that it is highly probable that Muḥammad’s Jewish contacts before going to Medina were “heretical, anti-Rabbinic Jews” and that “a number of terminological and ideological details suggest the Qumran sect” (Qumran Studies [New York: Schocken Books, 1957], 128). See more recently Patricia Crone, “The Book of Watchers in the Qur’ān,” in Haggai Ben-Shammai, Shaul Shaked, and Sarah Stroumsa (eds.), Exchange and Transmission across Cultural Boundaries: Philosophy, Mysticism and Science in the Mediterranean World (Proceedings of an International Workshop in Memory of Shlomo Pines; Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 2013), 16–51 and John C. Reeves, “Some Parascriptural Dimensions of the ‘Tale of Hārūt wa-Mārūt’,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 135 (2015): 817–842.

5 For a comprehensive analysis of the storytellers, see Lyall Armstrong, The Quṣṣās of Early Islam (Leiden: Brill, 2016).

6 The earliest extant manuscript is from the thirteenth century. The identity of the author and the dating of the work is, however, problematic. See Roberto Tottoli, Biblical Prophets in the Qur’an and Muslim Literature (Richmond, Surrey: Curzon, 2002), 151–155.

7 Genesis Rabbah 38:13 identifies Nimrod as the one who casts Abraham into the fire.

8 I have translated qurʾānic passages in consultation with several English translations: Abdel Haleem, The Qur’an (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010); Marmaduke Pickthall, The Koran (New York: Everyman’s Library, 1992 [1930]), and A. J. Arberry, The Qur’an Interpreted: A Translation (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1956; repr. 1996).

9 James Kugel, A Walk through Jubilees: Studies in the Book of Jubilees and the World of its Creation (Leiden: Brill, 2012), 83, and Adelman, The Return of the Repressed, 60, n. 35. For discussion of Jubilees, see Michael Segal, The Book of Jubilees: Rewritten Bible, Redaction, Ideology and Theology (Leiden: Brill, 2007) and Kugel, A Walk through Jubilees.

10 For a discussion of an inconsistency between chapter 48, which recounts the role Mastema played in derailing God’s plans to free the Israelites from Egypt, and chapter 49, where we read how “the forces of Mastema were sent to kill every firstborn in Egypt,” see Segal, The Book of Jubilees, 214–228, and Kugel, A Walk through Jubilees, 229–230.

11 Translation from James C. VanderKam, The Book of Jubilees: A Translation (Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium 511; Scriptores Aethiopic 88; Louvain: Peeters, 1989). Scholars have asserted that the passage responds to Mesopotamian traditions dealing with the origin of the seed-plow. For a detailed discussion of the parallels between Genesis 15:11 and Jubilees 11, as well as an excellent treatment of the function of the ravens episode in Jubilees, see Andrew Teeter, “On ‘Exegetical Function’ in Rewritten Scripture: Inner-Biblical Exegesis and the Abram/Ravens Narrative in Jubilees,” Harvard Theological Review 106 (2013): 373–402.

12 Most lists of Abraham’s trials enumerate ten, and seem to date to the second century BCE. Ten tests are mentioned in Mishnah, Avot 4:3 and Avot de-Rabbi Nathan 33, in addition to Pirqei de-Rabbi Eliezer 26. See Scott B. Noegel, “Abraham’s Ten Trials and a Biblical Numerical Convention,” Jewish Bible Quarterly 31 (2003): 73–83 and Lewis Barth, “The Lection for the Second Day of Rosh Hashanah: A Homily Containing Ten Trials of Abraham,” Hebrew Union College Annual 58 (1987): 1–48 [Hebrew]. See also Jo Milgrom, The Akedah: A Primary Symbol in Jewish Thought and Art (Berkeley: The Bibal Press, 1988).

13 For a discussion of extra-scriptural sources that understand Genesis 15:12–16 as a test, see James Kugel, The Bible as it Was (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 168–170.

14 Sebastian P. Brock, “Abraham and the Ravens: A Syriac Counterpart to Jubilees 11–12 and Its Implications,” Journal for the Study of Judaism 9 (1978): 135–152.

15 Michael P. Knowles, “Abram and the Birds in Jubilees 11: A Subtext for the Parable of the Sower?” New Testament Studies 41 (1995): 145–151, views the episode as an expansion of the biblical narrative (possibly inspired by Genesis 15:11) that not only restores the agricultural cycle in the Noahide covenant but also serves to demonstrate Abraham’s success in averting Mastema’s endeavors to rob humans of the fruits of their toil. James C. VanderKam, The Book of Jubilees (Sheffield: Sheffield, 2001), 46–47, also maintains that Abraham’s chasing the birds might be related to Genesis 15:11. See also Michael Stone, Armenian Apocrypha Relating to Abraham (Early Judaism and its Literature 37; Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2012), 18–20, who analyzes the motif as found in Armenian apocryphal literature. Scholars have also made connections between the episode in Jubilees and the apocryphal Epistle of Jeremiah. Drawing on the connection Klaus Berger makes in a lengthy footnote to his translation of Jubilees, Das Buch der Jubiläen (Jüdische Schriften aus hellenistisch-römischer Zeit 2.3; Gütersloh: Gerd Mohn, 1981), 388, n. 11e, between Jubilees and the Epistle of Jeremiah, Cory Crawford argues that the epistle may have been in existence before Jubilees. For an alternative point of view, see Teeter, “On ‘Exegetical Function’ in Rewritten Scripture,” 383–384, who asserts the dependence of Jubilees on the Epistle of Jeremiah to be tenuous.

16 Segal, The Book of Jubilees, 101. As he notes, there is no room for pure dualism in a monotheistic religion, since God is in charge of all forces in the world.

17 Karel van der Toorn and Pieter van der Horst, “Nimrod before and after the Bible,” Harvard Theological Review (1990): 1–29, 18. Gen 6:4 refers to the gibborim, “the heroes of old, the men of renown,” which is not necessarily bad, and in fact conveys a positive connotation; however, the next verse mentions the wickedness of humanity. Thus, exegetes link the two verses and interpret gibborim negatively. For examples, see Kugel, The Bible as it Was, 110–112.

18 For a discussion of this story in Pseudo-Philo, see my The Family of Abraham, 91–93.

19 Van der Toorn and van der Horst, “Nimrod before and after the Bible,” 20.

20 b. Ḥagigah 13a notes that he is the grandson of Nimrod.

21 Josephus also refers to Nimrod as inciting the people against God and to build a tower in defiance; see Jewish Antiquities 1.113–114.

22 Genesis Rabbah 38:13; b. Eruvin 53a; b. Pesaḥim 118a; and Song of Songs Rabbah 8:10. Leviticus Rabbah states that Nimrod sentenced Abraham to be burned.

23 In Deuteronomy Rabbah 2:27, the ministering angels intervene on Abraham’s behalf by alerting God to the fact that Amraphel was about to sentence Abraham to death, but God rescues Abraham from the fire.

24 Van der Toorn and van der Horst, “Nimrod before and after the Bible,” 28–29.

25 Ibid., 29.

26 Max Grünbaum, Neue Beitrage zur Semitischen Sagenkunde (Leiden: Brill, 1893), 52.

27 See Shari L. Lowin, “Narratives of Villainy: Titus, Nebuchadnezzar, and Nimrod in the ḥadīth and midrash aggadah,” in Paul M. Cobb (ed.), The Lineaments of Islam: Studies in Honor of Fred McGraw Donner (Leiden: Brill, 2010), 261–296, 266–274.

28 For an English translation of Abraham’s confrontation with Nimrod in Thaʿlabī, see ʿArāʾis al-majālis fī qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, or ‘Lives of the Prophets’ as Recounted by Abū Iṣḥāq Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad ibn Ibrāhīm al-Thaʿlabī, trans. William M. Brinner (Leiden: Brill, 2002), 124–133, and for an English translation of Ṭabarī, see The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume II: Prophets and Patriarchs, trans. William M. Brinner (New York: SUNY Press, 1987). We read in Ṭabarī:

Then God sent a wind that flung the top of Nimrod’s tower into the sea. The rest of the building then collapsed and fell down on them, knocking over their houses. Nimrod was gripped by a shudder when the tower fell and, because of the fear, the tongues of the people became confused and they spoke in seventy-three languages. Therefore, the place was named Babel, because the languages became confused (tabalbala) therein. That is His word, “The roof fell down over them from above, and punishment came upon them from somewhere they did not suspect ([Q] 16:26).”

Ṭabarī, History of al-Ṭabarī II, trans. Brinner, 163.

29 See, for example, Muqātil b. Sulaymān, Tafsīr Muqātil ibn Sulaymān, ed. ‘Abd Allāh Maḥmūd Shiḥātah (5 vols.; Cairo: Al-Hayʾah al-Miṣriyyah al-‘Āmmah li’l-Kitāb, 1979–1989): 3.613; Muḥammad b. Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, Jāmi‘ al-bayān ‘an ta’wīl ay al-Qur’ān (Cairo: Sharikat Maktabat wa-Maṭba‘at Muṣṭafā al-Bābī al-Ḥalabī wa-Awlādihi, 1954), 17.45; ibid., Taʾrīkh al-rusul waʾl-mulūk (Leiden: Brill, 1879–1901); Ahmad b. Muḥammad al-Thaʿlabī, Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyā’ al-musammā ʿĀrāʾis al-majālis (Cairo: Maṭba‘at al-Anwār al-Muḥammadiyyah, n.d.), 93; Abū’l-Fidā’ Ismā‘īl Ibn Kathīr, Tafsīr al-Qurʾān al-ʿaẓīm (Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-Islāmiyyah, n.d.), 12.33. For a more extensive list of additional sources, see Lowin, The Making of a Forefather, 262 n. 3.

30 Philo refers to Nimrod as an Ethiopian since he is the son of Cush. This depiction of Nimrod is found in later Jewish sources. Genesis Rabbah 42:4 also refers to Nimrod as a Cushite (Ethiopian).

31 Quoted material taken from The Tales of the Prophets of al-Kisāʾī, trans. Wheeler M. Thackston (Boston: Twayne, 1978). I use Isaac Eisenberg’s edition in Vita Prophetarum auctore Muḥammed ben ʿAbdallāh al-Kisaʾi ex codicibus, qui in Monaco, Bonna, Lugd. Batav., Lipsia et Gothana asservantur, ed. Isaac Eisenberg (Leiden: Brill, 1922).

32 Tales of the Prophets, trans. Thackston, 142.

33 Ibid.

34 Tales of the Prophets, trans. Thackston, 142–143.

35The episode also conjures up the image of Jesus bringing clay birds back to life, found in the Infancy Gospel of Thomas and Q 5:110, an association that Tzvi Novick astutely noted in a private correspondence. I am most grateful to him for drawing my attention to these connections and associations. To be sure, the episode conjures up more than one association. On the motif of ravens returning to their place, see Tzvi Novick, “Scripture as Rhetor: A Study in Early Rabbinic Midrash,” Hebrew Union College Annual 82–83 (2011–2012), 37–59, 43 n. 20. For a discussion of the connection between Genesis 15 and the ravens episode in Jubilees, see VanderKam, The Book of Jubilees, 46–47 and Knowles, “Abram and the Birds.”

36 Ṭabarī, History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume II, trans. Brinner, 134.

37 For a discussion of Nimrod in ancient and late antique Jewish texts, see van der Toorn and van der Horst, “Nimrod before and after the Bible.”

38 Aviva Schussman, “Sipurei ha-Nevi’im ba-Masoret ha-Muslemit [Stories of the Prophets in the Muslim Tradition]” (Ph.D. diss., Hebrew University, 1981).

39 Many scholars have explored PRE’s Islamic milieu, as well as compared motifs and narratives found in PRE and Islamic sources. See, for example, B. Heller, “Muhammedanisches und Antimuhammedanisches in den Pirke Rabbi Eliezer,” Monatsschrift für die Geschichte und Wissenschaft des Judenthums 33 (1925): 47–54; J. Heinemann, Aggadot ve-Toldotehen: Aspaqlariyat ha-Folqlor (Tel Aviv: Don, 1975), 220–225; Aviva Schussman, “Abraham’s Visits to Ishmael—the Jewish Origin and Orientation” [Heb.], Tarbiz 49 (1980): 325–345; Gordon D. Newby, “Text and Territory: Jewish-Muslim Relations 632–750 CE,” in Benjamin H. Hary, John Hayes, and Fred Astren (eds.), Judaism and Islam: Boundaries, Communications and Interactions (Leiden: Brill, 2000), 83–95; Adelman, The Return of the Repressed; and Michael E. Pregill, “Some Reflections on Borrowing, Influence, and the Entwining of Jewish and Islamic Traditions; or, What the Image of a Calf Might Do,” in Majid Daneshgar and Walid Saleh (eds.), Islamic Studies Today: Essays in Honor of Andrew Rippin (Leiden: Brill, 2017), 164–197.

40 Yoram Erder, “The ‘Prince Mastema’ in a Karaite Work” [Heb.], Meghillot: Studies in the Dead Sea Scrolls 1 (2003): 243–246.

41 Ibid.

A Migrating Motif

Abraham and his Adversaries in Jubilees and al-Kisāʾī

Introduction

Comparisons are often made between haggadic literature and Islamic stories found in the ḥadīth and qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ.1 Given that at times narratives expand and characters are fleshed out in a similar fashion, it is difficult to avoid making such comparisons and discussing the relationship between Jewish and Islamic sources.2 Efforts to forge a relationship—in whichever way this relationship is conceived—between Jewish and Muslim extra-scriptural narrative expansions have mainly focused on rabbinic material found in midrashic corpora and the Talmuds.

The relationship between early Jewish pseudepigraphic works and late rabbinic and early medieval literature continues to captivate scholarly attention, and for good reason. How does one account for the appearance of the literary building blocks of Second Temple literature in later Jewish and Christian sources? For example, how did the author of Pirqei de-Rabbi Eliezer have access to pseudepigraphic works? Or perhaps we should ask, did the author have access to pseudepigraphic works? If so, in what language were they transmitted? Hebrew or Aramaic? Greek or Latin? Were they transmitted by way of Semitic translations of later recensions? As John Reeves asks, did works like 1 Enoch, Jubilees, and the Testament of Levi

re-enter Jewish intellectual life after a long hiatus, due to a fortuitous manuscript discovery or a simple borrowing of intriguing material from neighboring religious communities? Is it possible to trace a continuous ‘paper trail’ leading from Second Temple scribal circles down to the learned haggadists and interpreters of medieval Judaism?3

Moreover, can such evidence possibly lead to Islamic circles?4

In light of the dissemination of Jewish pseudepigraphic works in the medieval period, we should consider more capacious comparisons that include pre- and para-rabbinic material. As a gesture toward the endeavor to explore how Second Temple literature echoes in medieval works, what follows is a preliminary literary analysis that compares the role the birds trope plays in the story of Abraham and his adversaries in Jubilees, a second-century BCE work that purports to be God’s revelation to Moses on Mount Sinai, and in Muḥammad b. ʿAbd Allāh al-Kisāʾī’s Tales of the Prophets. I hope my broader examination of the story of Abraham’s encounter with an adversary, Mastema in Jubilees and Nimrod in Kisāʾī, will serve as a case study for interrogating the ways in which literary elements migrated across geographic and temporal lines, and the role they play in shaping the reception of scriptural narratives. The purpose here is not to locate a point of origination, but rather to detect resonances between Jewish and Islamic narratives over a broad span of time.

We will first assess the ways in which Abraham’s arch-nemesis Nimrod functions as an anti-hero similar to the angel Mastema in Jubilees. We will then turn to two episodes involving Abraham and birds and examine their respective roles within each narrative arc. In Jubilees, whole birds are sent away and scattered; in Kisāʾī, severed, scattered pieces of birds are made whole. In both instances, however, the story functions to give expression to Abraham’s power over a malevolent figure who challenges God’s omnipotence. Both bird episodes, moreover, function to interpret a scriptural verse.

This analysis of how each episode functions in stories about Abraham’s battle against an enemy will not demonstrate a direct relationship between these works—although that is not entirely inconceivable. Rather, it will highlight the literary parallels and distinctions that might, even modestly, contribute to our assessment of the qiṣaṣ genre with respect to its theological framework and worldview, as well as its relationship to other forms of scriptural expansion.

The qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ genre

The Islamic tales of the prophets (qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ) are stories about the lives of the prophets of the Qurʾān. They flesh out the qurʾānic narrative with all kinds of fascinating and fantastical details about the prophets’ character traits and episodes in their lives. Many of the motifs and tropes employed in these accounts are also found in Christian and Jewish literature; some even date back to antiquity. Like other para-scriptural texts, these stories help shape one’s knowledge and impression of figures such as Adam, Noah, Abraham, Ishmael, Isaac, Moses, and Jesus, so much so that often our common understanding of the prophets, as well as other characters in the prophets’ narratives (for example Sarah, Mary, or Iblis), is actually a conflation of details gleaned from the Qurʾān itself and extra-scriptural sources such as the tales.

Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ also refers to a genre of literature and not just to a specific qiṣṣah (story). Furthermore, while one finds these stories in qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ collections, the stories appear in other genres of literature such as tafsīr (qurʾānic exegesis) and taʾrīkh (historiography). The different renditions disseminated widely across genres attest to their popularity and function in fleshing out the Islamic metanarrative and fostering theological and moral teachings of the Qurʾān. To be sure, some plots, characterizations, tropes, and motifs may have been in widespread circulation centuries before the composition of the Qurʾān, and were quite familiar to Jews and Christians. The manner in which elements of these stories were synthesized is therefore all the more important for understanding the role these stories played in the Islamic tradition of the medieval period, and how they relate to similar stories in Jewish and Christian literary traditions.

Narrative embellishments and adaptations are part and parcel of how stories maintain their cultural purchase and staying power throughout the centuries. This is certainly the case when taking into account the vast literary circulatory system of the Near East that includes not only accounts of biblical and qurʾānic heroes, but also their antagonists. Advances in the study of ancient Judaism, as well as early Christian and Islamic literature, have clearly demonstrated the ways in which stories in written and oral form migrated throughout the Near East. In the process, they were expanded and embellished to suit the desires and needs of those transmitting tales for purposes of edification and entertainment.

Narrators (quṣṣāṣ; sing. qāṣṣ) were respected figures in early Islamic society, serving not only to recite the Qurʾān, but also to expound it in an effort to stir the piety of listeners and impart moral lessons. While the story-tellers garnered esteem and respect during the early Islamic period, over time the liberties they took and excessive embellishments they made tarnished their reputations. Yet despite their marginalization, even today within the realm of popular culture, the stories themselves continue to ignite the imagination and interest of readers.5

The collection of tales of Kisāʾī stands out as one of the most popular medieval collections.6 It narrates the adventures and miraculous works of the prophets, and in some instances their escape from imminent danger as well as their victorious battles against the forces of evil. Such is the case of the episode of Abraham’s encounters with Nimrod (Namrūd). The story takes qurʾānic episodes about Abraham’s clashes with non-believers and relates his powerful victory over Nimrod.

In the Qurʾān, Abraham has to contend with the idol worshippers around him who cast him into the fire (see Gallery Image A), but he lacks a specific antagonist.7 Adam is challenged by Satan, and Moses by Pharaoh, but Abraham has no evil counterpart mentioned by name. In Sūrat al-Baqarah, however, reference is made to an arrogant, blaspheming ruler who confronts Abraham and contends that he, not God, has power over life and death:

[Prophet,] have you not considered the one who argued with Abraham about his Lord, because God had given him kingship? When Abraham said, “My Lord is the one who gives life and death,” he said, “I give life and death.” Abraham said, “Indeed, God brings up the sun from the east, so bring it up from the west.” The disbeliever was stupefied. God does not guide the wrongdoers. (Q Baqarah 2:258)8

Who is the leader who claims to be equal to Abraham’s Lord? Although the Qurʾān does not identify him, extra-qurʾānic tales and exegetical traditions not only give him a name—Nimrod—but also recount his wickedness in horrifying detail.

Abraham, Mastema, and the birds in Jubilees

The name of Mastema, a personification of evil, means “loathing,” “hating,” and most probably is derived from the Hebrew verbal root s-ṭ-m, meaning “to despise, to harbor hostility, enmity.”9 He is the chief angel of loathing, sar mastema, accorded a higher status than the other spirits. Mastema, referred to as Satan in Jubilees 10:11, leads the forces of evil in the world, and, like Satan in Job, negotiates with God.

Mastema plays a central role in Jubilees, in a work that, through its retelling of the story of Genesis and Exodus, focuses on the restoration of Israel. At every turn, his attempts to test faith in God, that is, to take Israel off its course toward restoration, are met with defeat. Whether tempting Abraham to disobey God’s command to sacrifice Isaac or conniving during the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt, Mastema is God’s nemesis. He tempts humans to commit idolatry (Jub. 11:4–6), prompts God to command Abraham to sacrifice Isaac (17:16), and, on Moses’ way down to Egypt, he threatens Moses’s life (48:9–10 and 12). In short, on the playing field where good and evil battle for human souls, Mastema, the ruler of the evil realm, is God’s quintessential archenemy.10

Let us look at a specific example that we will revisit when we examine Nimrod’s encounters with Abraham in Kisāʾī. Just after the birth of Abraham’s father, Terah, Mastema sends ravens to devour all the seed before it could be plowed:

Then Prince Mastema sent ravens and birds to eat the seed which would be planted in the ground and to destroy the land in order to rob mankind of their labors. Before they plowed in the seed, the ravens would pick (it) from the surface of the ground… The years began to be unfruitful due to the birds. They would eat all the fruit of the trees from the orchards. (Jub. 11:11–13)

The story continues with the announcement of Abraham’s birth and his awareness of the idolatry around him:

The child began to realize the errors of the earth—that everyone was going astray after the statues and after impurity. His father taught him the art of writing. When he was two weeks of years [i.e., fourteen years old], he separated himself from his father in order not to worship idols with him. He began to pray to the creator of all that it might not fall to his share to go astray after impurity and wickedness” (Jub. 16-17).

Abraham would go out with everyone during the sowing season “to guard the seed from the ravens… ”

As a cloud of ravens came to eat the seed, Abram would run at them before they could settle on the ground. He would shout at them… and would say: “Do not come down; return to the place from which you came!” And they returned. That day he did (this) to the cloud of ravens seventy times. Not a single raven remained in any of the fields where Abram was. All who were with him in any of the fields would see him shouting: then all of the ravens returned (to their place). His reputation grew large throughout the entire land of the Chaldaeans. All who were planting seed came to him in this year, and he kept going with them until the seedtime came to an end. (Jub. 11:19–21)11

Even though there is no mention of Gen 15:11, it seems that the story embellishes this verse: “When the birds of prey descended upon the pieces, Abram drove them away.” In this chapter of Genesis, in a formalized ceremony, God affirms his promise to Abraham of land, nation, and blessing (cf. Genesis 12). He commands Abram (his name at the time) to do the following: “Bring Me a three-year-old heifer, a three-year-old she-goat, a three-year-old ram, a turtledove, and a young bird” (Gen 15:9). When Abram brought them, he cut them in half, placing them opposite each other, but he did not “cut up the bird” (Gen 15:10). It is at this moment that “birds of prey descended upon the pieces, Abram drove them away” (Gen 15:11).

Jubilees introduces Abraham (Abram) as pious and unlike the people around him. He proves himself a leader and saves the people from famine. His fame was known throughout the land of the Chaldaeans. Abraham prays to the creator of all and in a sense is rewarded by being endowed with the power to ward off the birds. Mastema poses a challenge that Abraham, who turns to God, is able to overcome. As we will see shortly, there are parallels, despite obvious differences, between this episode in Abraham’s life as depicted in Jubilees and that in Kisāʾī.

Classical rabbinic literature says very little if anything about Genesis 15:11. Genesis Rabbah 44.16, for example, mentions that Abraham drove the birds of prey away, and generations of Jews to follow will merit from Abraham’s pious act. The rabbis do not interpret the verse as one of the trials Abraham faces.12 However, the passage in Jubilees elaborates upon the biblical narrative and amplifies Abraham’s prowess in warding off the birds, not only once, but seventy times in one day! Although it is not listed in the seven trials Abraham faces listed in Jubilees (Jub. 17:17–18), by thwarting Mastema, Abraham nonetheless displays his obedience and worthiness to cut a covenant with God.13

In later Jewish traditions there is no parallel to this passage in Jubilees, but as Sebastian Brock demonstrates, it has a curious variant that is preserved in Syriac sources (viz., the Catena Severi and the letter of James of Edessa to John of Litarba)14 Brock argues that the schema of the Syriac form of the tradition is, in fact, anterior to the basis of the pattern in Jubilees, and in Jubilees it serves to introduce Abraham as the inventor of the plow. Whereas in the Syriac texts the ravens are sent by God as punishment for idolatry, in Jubilees they are sent by Mastema. Like the Aqedah (the “binding of Isaac”) in Jubilees, which is initiated not by God but by Mastema, here too Mastema functions as a foil. The birds episode is presented as Mastema’s opposition to God which Abraham meets successfully.15

Jubilees depicts a world in which, as Segal describes it, “heavenly forces and earthly nations are divided in a seemingly dualistic system… the evil divine powers rule over the wicked people, while the good forces govern the righteous.”16 Abraham is portrayed as one who disavows idolatry, turns to God, and fights against Mastema, the leader of the forces of evil. Genesis 15:11 may be the scriptural occasion for this narrative amplification, although reference to the covenantal ritual is explicitly lacking. Be that as it may, the story in Jubilees depicts Abraham as heroically foiling Mastema’s attempt to disrupt the agrarian cycle, threaten humanity, and challenge God’s authority. The birds episode functions as a trope for Abraham’s power as well as piety.

Nimrod in Second Temple and rabbinic sources

In the book of Genesis, Nimrod is the son of Cush, and is a mighty hunter. Whereas the Bible tells us hardly anything about Nimrod, post-biblical traditions amplify and develop his character. Pieter Van der Horst maintains that Philo of Alexandria is the earliest post-biblical writer who connects the gibborim, the offspring of the sons of God who mate with humans in Genesis 6:4, to Nimrod, who is called a gibbor (one who is powerful) in Genesis 10:8–9.17 According to Philo’s commentary on Genesis 6:4 (On Giants, 65–66), Nimrod is an example of the sons of the earth who succumb to the nature of the flesh instead of being governed by reason. He writes: “For the lawgiver says, ‘he began to be a giant on the earth’ (Gen 10:8), and his name means desertion.” Philo, moreover, provides an etymology for his name: “desertion.” We find this notion in other traditions that explain his name from the Hebrew marad, “to rebel” against God, and in this sense we detect Philo’s notion of Nimrod as one who deserts God.

Perhaps the earliest attestation of Abraham’s encounter with Nimrod is found in Pseudo-Philo’s Biblical Antiquities, a work dated to the second half of the first century CE. Chapter 5 of this work opens with the statement that the sons of Ham made Nimrod their leader, and chapter 6 develops the story between Abraham and Nimrod. The leaders of the tribes of Shem, Ham, and Japheth plan to build a tower in Babel; however, twelve men refuse to participate out of devotion to the Lord. Abraham, one of the twelve, is locked up with the others, and is then cast into a fire.18 As van der Horst notes, we cannot be certain whether Pseudo-Philo is the originator of the fire motif, nor can we claim that the confrontation between Abraham and Nimrod was widespread at the time since it is absent in Josephus.19

Rabbinic traditions associate Nimrod with Amraphel, a king mentioned in Genesis 14, and depict him as leading a worldwide rebellion against God, and as ordering that Abraham be thrown into a fiery furnace. In Genesis Rabbah 42:4, Amraphel is known also as Nimrod because he incited the world to rebel (himrid, a play on his name, nimrod). According to the Babylonian Talmud (b. Pesaḥim 94b), Nebuchadnezzar is a descendant of Nimrod.20 Elsewhere in the Talmud (b. Ḥagigah 53b) he is associated with the Tower of Babel (or “Temple of Nimrod”),21 and other rabbinic sources refer to Nimrod casting Abraham into the fire.22 Leviticus Rabbah 27:5 and Ecclesiastes Rabbah 3:18 mention that Nimrod pursued Abraham. Deuteronomy Rabbah 2:27 refers to Abraham’s encounter with Amraphel, his arrest, and his trial by fire.23

Throughout the medieval period, Nimrod was depicted as a giant who built the tower of Babel, and his image as God’s archenemy grew in Jewish, Christian, and Islamic circles. Van der Horst writes:

Haggada in which Nimrod is mentioned explicitly is found for the first time in the first century CE. But since we know from Jubilees, from Pseudo-Eupolemus, and from Philo the epic poet, that already in the second century BCE there was Abraham haggada in which a connection had been made between Abraham and the giants, and between the tower of Babel and Abraham, it is hardly thinkable that the Nimrod connection was made only two centuries later.24

He continues by considering that one of the earliest factors that contributed to this process was “the circumstance that the biblical text called Nimrod a gibbor/gigas, using the same word as in Gen 6:4 for the offspring of the rebelling sons of God.”25

I would also suggest the possibility that the more fully developed Nimrod resonates with Mastema, who asks God (Jub. 10:8–9) to leave under his domain some of the giants, that is, the Nephilim of Genesis 6:4. While one is hard pressed to regard Mastema as a prototype, one cannot ignore factors that evoke comparison, namely that both are leaders of wicked forces that clash against Abraham in a series of challenges, one of which involves birds. The figure of Nimrod as portrayed in Kisāʾī’s Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ helps us to draw that comparison.

Abraham, Nimrod, and the birds in the tales of the prophets

In Islamic literature, Nimrod and Pharoah symbolize the boastful, arrogant ruler.26 In Kisāʾī’s Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, Nimrod is a tyrant, a giant (jabbār in Arabic). He is the unrelenting force of evil that keeps humanity from righteousness. He builds a palace, slays the first-born male, and dies after a gnat enters his brain and gnaws at it for four hundred years. That he dies from a gnat entering his nostril and gnawing on his brain is found in many Islamic tales about him, and parallels the well-known story of the demise of Titus in rabbinic sources.27

Islamic collections of the tales of the prophets do not all include the same stories, and renditions differ from collection to collection despite common threads. For example, the depictions of Nimrod of Abū Isḥāq Aḥmad b. Muḥammad b. Ibrāhīm al-Thaʿlabī (d. 427/1035) and Abū Jaʿfar Muḥammad b. Jarīr al-Ṭabarī (d. 310/923) include tales of the building of the tower of Babel not found in Kisāʾī, but as noted earlier, Nimrod is identified in rabbinic sources with the tower .28 Kisāʾī’s characterization of Nimrod, however, is rather elaborate, and his rendition of Nimrod’s battle against Abraham is one of the most captivating tales among the collections.29 His Nimrod takes on a similar function as Mastema in Jubilees—the primary force of evil that relentlessly attempts to keep humanity from righteousness. One specific element of the story as Kisāʾī frames it resonates with Mastema’s attempts to wage war against God: the episode of Abraham with birds. Indeed, while in rabbinic literature Nimrod is portrayed in opposition to God, the appearance of the episode of Abraham and the birds within Kisāʾī’s larger Nimrod account actually parallels that of the narrative of Mastema thwarting God and Abraham vanquishing his enemy in Jubilees.

To be sure, unlike Mastema who is an angel, a leader of wicked spirits, Kisāʾī depicts Nimrod as human, although one born accursed. When his mother delivered him at birth, “a thin serpent came out of her womb and entered the boy’s nose.” When she took him into the wilderness to a shepherd to raise him, even the cattle would not go near the boy. The “black, flat-nosed boy” was suckled by a tigress.30 When he grew up, he became a highway robber, plundered towns and cities, stole from people, and took women captive.31 Iblis (Satan) teaches him the sciences of sorcery and soothsaying. He deems himself the creator of all and expects humans to worship him. He distributes food to his subjects, dismissing, however, without supply those who refuse to confess his supremacy over the God of Abraham.

Kisāʾī’s story of Abraham and Nimrod is relatively long and elaborate. Nimrod asks Abraham to follow his religion and worship him, but Abraham refuses, thus setting off a series of contests between Nimrod and Abraham. The story expands upon the qurʾānic passage in Surat al-Baqarah:

[Prophet,] have you not considered the one who argued with Abraham about his Lord, because God had given him kingship? When Abraham said, “My Lord is the one who gives life and death,” he said, “I give life and death.” Abraham said, “Indeed God brings up the sun from the east, so bring it up from the west.” The disbeliever was stupefied. God does not guide the wrongdoers. Or take the one who passed by a ruined town. He said, “How will God give this [town] life when it has died?”… And when Abraham said, “My Lord, show me how You give life to the dead,” He said, “Do you not believe, then?” “Yes,” said Abraham, “but just to put my heart at rest.” So God said, “Take four birds and train them to come back to you. Then place them on separate hilltops, call them back, and they will immediately come back to you; know that God is all powerful and wise.” (Q 2:258–260)

The Qurʾān identifies neither the disbeliever nor the passerby. Moreover, there is no context given for Abraham’s request to God for an explanation of the resurrection.

In Kisāʾī, the qurʾānic passage is contextualized within the broader battle between Nimrod and Abraham. Nimrod boldly asserts that his kingdom is greater than God’s; a debate as to who has greater power ensues. Nimrod’s competition for sovereignty even extends to the non-human realm. A beautiful cow proclaims, “Enemy of God, were I given leave by my Lord, I would gore you so that afterwards you would never be able to eat again!”32 He kills the cow but God restores it to life.

The story continues: “Abraham turned and saw a slave-girl in the palace. She was nursing Nimrod’s small daughter. Suddenly the girl leapt from her mother’s lap, faced Nimrod and said, ‘Father, this is God’s prophet Abraham.’ And Nimrod ordered her cut to pieces.”33 This is in contrast to God who resurrects the dead, which is mentioned several times in Abraham’s encounters with Nimrod, but also throughout the work as a whole. Within this battle of words and deeds we read:

[Abraham said:] “Verily God is not incapable of anything; he is capable of all things.” “What do you know of His power?” asked Nimrod. “My Lord is the one who giveth life, and killeth,” (Q 2:258) said Abraham. “I give life, and kill,” said Nimrod. “How can you do that?” asked Abraham. “I set free from prison men sentenced to death, and I kill men not sentenced to die.” “My Lord does not give life or cause death thus,” said Abraham. “He quickens the dead and He causes death to the living yet kills them not. But, O Nimrod, god bringeth the sun from the east, now do thou bring it from the west.” Whereupon Nimrod was confounded. Then Abraham called upon his Lord and said, “O Lord, show me how thou wilt raise the dead” (Q 2:260).

Kisāʾī adds colorful detail to God’s commands to Abraham to take four birds and bring them back to him:

Abraham took a white cock, a black raven, a green dove, and a peacock, killed them, cut off their heads, mixed up the blood and feathers, and scattered their flesh on four mountain tops. He then called them, and the heads went out of his hands, each returned to its own body, saying, “There is no god but God; Abraham is God’s apostle to Nimrod and his people.”34

The qurʾānic verses are here given a context, namely the contest between Nimrod and Abraham. The cut-up birds coming back to life, in the context of Abraham’s ordeal, is reminiscent of Abraham ordering the ravens in Jubilees to return to the place from which they came after Mastema sent them to eat the seed.35 In that account, Abraham develops such a reputation for his ability to ward off the birds that everyone planting seed would seek his assistance. Abraham is victorious over both Mastema and Nimrod.

In both instances, Abraham demonstrates the power of God over evil. The story of the birds appears in the context of Mastema’s attempts to defy and defeat God by starving humans, thus bringing about their demise, whereas in Kisāʾī’s Tales of the Prophets, the story of the birds serves as evidence of the all-powerful God who gives life and brings the dead to life. It is one more victory in Abraham’s campaign against Nimrod, and idolatry in general. Despite the differences not only in the stories, but also in what happens to the birds in each narrative, the motif of Abraham and the birds plays a similar function in both stories of his victory over evil.