PDF

Download

Citations

Click and drag then release to select a passage to cite.

Annotations

How to submit annotations to Mizan Journal articles:

your work is published.

Search within

The Cloak of Joseph

A Qiṣaṣ al-Anbiyāʾ Image in an Arabic and a Hebrew Poem of Desire

Image

Audio

Video

Chart or Graph

The Cloak of Joseph

A Qiṣaṣ al-Anbiyāʾ Image in an Arabic and a Hebrew Poem of Desire

Introduction

When one studies the “stories of the prophets” in Islamic tradition, one usually looks for them in their expected milieu, the exegetical literature or the collections of qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ materials. However, religious literature relating to the interpretation of the Qurʾān is not the only setting in which such narratives appear. Rather, as we will see, such accounts and their attendant imagery were so entrenched in Islamic society, in Muslim Andalusia in particular, that we find qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ materials appearing even in secular poems of desire, in which they are used to subversive ends. Perhaps more surprisingly, in one case an Islamic qiṣaṣ motif has slipped across confessional bounds and asserted itself in a secular Hebrew desire poem by a Spanish Jewish poet. Such is the situation regarding the motif of the cloak of the forefather Joseph and its startling appearance in both a homoerotic poem by the Ẓāhirī scholar Abū Muḥammad ʿAlī b. Aḥmad b. Saʿīd b. Ḥazm (384–456/994–1064) and in a heteroerotic poem by the Jewish scholar, general, and statesman, Samuel the Nagid (also known as Samuel b. Naghrela, 993–1055/6).

ʿIshq poetry in medieval Spain

The poems of both Ibn Ḥazm and Samuel the Nagid belong to a genre of secular poetry hailing from Islamic Spain known in Arabic as poems of ʿishq and in Hebrew as shirat ḥesheq. In such poems, the poet speaks as a human being engaged in a passionate relationship with another human being. In truth, they are poems of desire rather than of romantic love. This distinction between types of love can be found in the work of earlier Muslim scholars. For example, the litterateur, prose writer, and theologian Abū ʿUthman ʿAmr b. Baḥr al-Kinānī al-Baṣrī, known as al-Jāḥiẓ (d. 155/868), differentiated between ʿishq and another category of love with which it is sometimes incorrectly confused, ḥubb. Jāḥiẓ explains ḥubb as sentimental love, the type of love one feels for one’s family, or for God. While ḥubb constitutes the first stage of ʿishq, he writes, ʿishq requires both a sense of hawā (passion) and a physical component, sexual attraction. While ḥubb lacks the sexual component, sex constitutes the very defining characteristic of ʿishq.1 Sexuality and eroticism stand as key components of ʿishq poems as well.

While this category of poetry attained great heights in Muslim Spain, it was not wholly invented there. Rather, Andalusian ʿishq poems drew from eastern Arabic forms that predated it, mainly ʿUdhrite love poetry, named for the South Arabian tribe from which many of the earliest poets in this genre came. In the pre-Islamic era, love poetry was not an entirely independent poetic form, but rather appeared usually as part of the long ode-like qaṣīdah. These long mono-rhymed poems of often elaborate meter valorized the concerns and ideals of the pre-Islamic Bedouin society in which they developed. The poems celebrated and praised Arab bravery in war, Arab generosity, and frequently described battlefield or pastoral scenes. Love lyrics appeared as the nasīb, the amatory prelude to the poems. With the Islamic conquests and the Islamization of the Arabian Peninsula, especially under the Umayyad caliphate, the poems underwent Islamization as well; Islamic values replaced the pagan standards, and an urban focus replaced pastoral scenarios. Love poems that incorporated the themes of ʿUdhrite love then developed independently of the long qaṣīdah.

The Andalusian form of these love poems reflect many of the values visible in ʿUdhrite predecessors. Known also as pessimistic love poetry or chaste love poetry, ʿUdhrite love poetry presents readers with a highly conventionalized form that frequently speaks of lovers yearning for union with the beloved without any real hope of physical realization. The poems describe the beloved in physical terms, describing the body rather than the character. The beloveds’ bodies themselves are also presented in conventionalized terminology—dark-haired, dark-eyed, with a shape that resembles a date-palm—so that it can sometimes seem there is but one beloved behind a great majority of the poems. The poems speak of the horrific suffering inflicted on the lover by their forced separation from the beloved, and of the cruelty of the beloved who knows of the lover’s suffering but seems either uninterested in alleviating it or actively interested in extending it. Due to this cruelty or apathy, the beloveds’ bodies are also often described as weapons causing grave pain to the lover both up close and at a distance: fingers stab, eyes ensnare, breasts poke like arrows, sprouting beards prick like thorns.2 In adapting ʿUdhrite poems, the Andalusian love poets—both Muslim and Jewish—preserve many of these conventions. However, in at least two ways, Andalusian poets were not quite as forlorn as their ʿUdhrite predecessors. While they suffered in their beloved’s absence, the poets from Spain often sound as if they are recalling actualized physical intimacy which they hoped to re-create or, in some cases, as if they were describing an episode of physical intimacy as it unfolded. Additionally, ʿUdhrite poets were apt to die from their love-suffering; Andalusian poets met their deaths far less often.

Perhaps somewhat surprisingly given the sexualized nature of ʿishq poetry, qurʾānic imagery and storylines not infrequently find their way into the Arabic poems. Such religious references form an updated version of a pre-Islamic convention in which pre-Islamic Arabic poets incorporated figures and themes from Arabic literary tradition and history into their poems. When secular poetry writing came to Islamic Spain, the Muslim poets added or replaced these with qurʾānic and Islamic historical or religious figures. When Andalusian Jews began writing Hebrew poetry on the same model, they replaced the Muslim imagery with allusions to the Bible and midrash.3 For both the pre-Islamic and the Andalusian Muslim poets, incorporating such figures and story-lines into their desire poems was also a way of playing with their audiences. As Ross Brann writes, both Muslim and Jewish poets incorporated sacred imagery and language into their secular poems in order “to create the false impression of irreverence, and thereby entertain the audience (or reader).”4

What is particularly interesting about this irreverent use of scripture is that it appears especially frequently in the secular desire poems of religious authority figures, men otherwise the most concerned with upholding the sacredness of religion and in promulgating its ideals and values. Thus, when such scholars of religion plunder their sacred texts in order to flesh out their heterosexually- and homosexually-charged desire poems, it begs our further attention, for in many cases, these scholar-poets use scripture as more than just poetic ornamentation. As we will see in one short example by Ibn Ḥazm, qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ referents can sometimes serve to sacralize what is an otherwise scandalous romantic attachment.

Ibn Ḥazm and the Cloak of Joseph

Abū Muḥammad ʿAlī b. Aḥmad b. Ḥazm (385–456/994–1064) hailed from a wealthy and learned Cordoban family who trained him in all the arts important to a well-educated medieval Spanish Muslim. He studied Arabic grammar, literature, lexicography, and rhetoric, as well as qurʾānic exegesis, theology, and fiqh (jurisprudence). Ibn Ḥazm grew to be an illustrious theologian, educator, legal authority, and poet. He wrote treatises on Islamic law, on ḥadīth, and even on other religious traditions, though the latter were mostly attacks against these faiths. Eventually, Ibn Ḥazm rose to head the Andalusian Ẓāhiri madhhab, which focused on a literalist reading of the Qurʾān.5

Well before his shift to Ẓāhirism, sometime around the year 414–415/1024, when he was in his late twenties, Ibn Ḥazm composed a thirty-chapter treatise on human love known as Ṭawq al-ḥamāmah (The Dove’s Neck-Ring). In this treatise, Ibn Ḥazm discusses the nature, causes, and aspects of love, behaviors in which lovers engage, and misfortunes that befall human lovers. He often illustrates these principles, which he discusses in prose form, with poetic compositions of his own creation.

In the chapter entitled “On Contentment” (al-qunūʾ), Ibn Ḥazm discusses the behavior of lovers who, separated from their beloveds, seek contentment in the physical objects that had once been in contact with them. In order to illustrate this point, Ibn Ḥazm cites a poem he himself composed. In this poem, he incorporates an example of such contentment-seeking by lovers, an example provided by God Himself.6

لمّا مُنعت القرب من سيّدي

ولجّ في هجري ولم ينصف

صرت بابصاري اثوابه

او بعض ما قد مسّه اكتفي

كذاك يعقوب نبي الهدى

اذ شفّه الحزن على يوسف

شمّ قميصًا جاء من عنده

وكان مكفوفًا فمنه شُفي

When I was prevented from being near to my master

and he insisted on avoiding me and did not treat me justly,

I began to content myself with his dress,7

or was contented with something he had touched;

Thus Jacob, the prophet of true guidance,8

when the grief for Joseph caused him suffering,

smelled the tunic9 which came from him,

and he was blind and from it got well.10

This touching poem conforms to the accepted styles and tropes of Andalusian ʿishq poetry in numerous ways. Most obviously, the poem opens with the tragic tale of two lovers who, in typical Andalusian fashion, are prevented from actualizing their union with one another. While the lover suffers from this enforced alienation, as a good Andalusian lover should, the beloved sadistically worsens his pain by avoiding him and generally treating him with unjust and unearned cruelty (line 2). Such cruel behavior is not particular to this poem’s beloved; rather, Andalusian beloveds were well-known for their harsh reactions to their lovers’ anguish. Despite such cruelty, the poem’s lover remains faithful to his beloved (lines 3–4), embodying yet another well-known Andalusian trope. For the Andalusians, if a lover even appeared to be able to move on from his declared beloved, he might be accused of never having been in love in the first place.11

Passion for the missing beloved usually resulted in physical pain on the part of Andalusian lovers. Their hearts burned, their insides were set aflame, they grew violently ill with grief and passion, they lost so much weight that, as Naṣr b. Aḥmad wrote, a ring that used to be too small for the lover’s finger now serves as his belt.12 Although Ibn Ḥazm’s lover does not mention his anguish outright, in comparing himself to Jacob—famously blinded by grief over his missing son Joseph—the lover drives home this point effectively.

While the use of religious heroes and storylines in secular poetry was not unusual, as already discussed, we ought to take note of the fact that here Ibn Ḥazm draws a comparison between a same-sex couple and two prophetic scriptural characters who are not only not erotically entangled with one another, but are father and son.13 In order to understand the full effect of this scriptural reference, let us briefly review the narrative of Jacob and Joseph as it appears in Sūrah 12 of the Qurʾān, Sūrat Yūsuf.

According to this “most beautiful of stories” (Q Yūsuf 12:3), the sons of the prophet Jacob grow jealous of the favoritism their father shows to their brother Joseph and “his brother,” and so they conspire to rid themselves of Joseph.14 They grab him, throw him into a well, and dip his shirt (qamīṣ), which they had apparently stripped from him, into “false blood,” thereby manipulating their father into thinking Joseph has been eaten by a wolf (see Gallery Image A). Joseph is then picked up by a caravan; sold to a man in Egypt; accused of raping the man’s wife; exonerated; brought before the town’s women to show off his beauty; sent to jail, where he meets some jailed dreamers; tells their future; interprets the king’s dream; gets out of jail; and eventually rises to become vizier in Egypt, in charge of the store-houses. Famine strikes Joseph’s homeland and his brothers are forced to come to Egypt in search of sustenance. Because they do not recognize him, Joseph manages to play with them sadistically for a bit (first he accuses them of being thieves, and then holds one of the brothers hostage until his “stolen” item is returned).

In the meantime, Jacob, back at home, has never ceased grieving for his lost son whom he does not believe is dead. His incessant crying for Joseph ultimately leads him to go blind (v. 84). Back in Egypt, Joseph eventually reveals himself to Jacob’s sons as their missing brother, and arranges to send word to his father that he is still alive. He sends Jacob his shirt (qamīṣ) with instructions to the messenger to place it over Jacob’s eyes, saying, “He [Jacob] will regain [his] sight” (v. 93, yaʾti baṣīr). As soon as the caravan leaves Egypt, Jacob—back home—announces that although his sons may once again accuse him of being a fool, he has suddenly detected Joseph’s scent wafting toward him (v. 94). The “bearer of good news” subsequently arrives and casts the shirt over Jacob’s face, and Jacob miraculously regains his sight (v. 96).15 The family then travels en masse to Egypt and father and son are joyfully reunited (v. 97–100).

As we can see, the overall themes of this qurʾānic account dovetail quite nicely with the themes of our Andalusian ʿishq poem. In both we find a moving tale of love between two people who are separated by forces beyond their control. We hear of the pathos of yearning and of the suffering caused by such unrealized love. We learn of the healing caused by not forgetting the missed beloved, of the redemptive value of loyalty. Thus, at first glance, Ibn Ḥazm’s use of this seemingly inappropriate scriptural referent (Jacob and Joseph are father and son and not ʿishq lovers, after all) appears to serve as a good illustration of the greater point he is trying to make about lovers, their faithfulness, and the methods they employ to soothe themselves in their moments of despair and distress.

Yet, if we look carefully at both the poem and the scriptural account, we notice that the poem’s presentation of the Jacob-Joseph narrative deviates in one small but very important way from the Qurʾān’s version. According to the poem, Jacob’s grief-induced blindness is cured when he smells the tunic that came from Joseph (shamma qamīṣ). However, this is not what we find in the Qurʾān itself.

In the Qurʾān, smelling and vision-restoration constitute two separate miracles, one leading up to the other but not actually causing it. The olfactory miracle occurs in verse 94, where as soon as Joseph’s caravan sets out from Egypt, Jacob suddenly detects the aroma of his long-lost son wafting toward him. While the aroma confirms to Jacob what he has believed all along (v. 17–18), that Joseph is not dead, it does not actually cure Jacob of his illness. In fact, the only result of this olfactory miracle is that Jacob’s family continues to consider him crazy, an accusation they have been lobbing at him since Joseph disappeared and Jacob first refused to accept his death (v. 95). Jacob’s sight returns two significant steps later. First the messenger sent by Joseph with his cloak reaches Jacob and then, as per instruction from Joseph, he throws the cloak over Jacob’s face. Only after both of these actions have been completed does Jacob regain his sight (v. 96). Unlike in Ibn Ḥazm’s poem which emphasizes the cloak’s healing smell, in the Qurʾān it is physical contact with the tunic that cures Jacob’s blindness.

While one might be inclined to think that Ibn Ḥazm here presents us with a brand new reading of the qurʾānic account of Joseph’s cloak, in which he shifts its power from the physical object itself to its aroma, in reality we find the shift from touch to smell in the qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ literature. According to Aḥmad b. Muḥammad al-Thaʿlabī (d. 427/1035), Muḥammad b. ʿAbd Allāh al-Kisāʾī (ca. fifth/eleventh c.), and Ibn Muṭarrif al-Ṭarafī (d. 453–4/1062, citing Isḥāq b. Bishr [d. 206/821]), when Joseph was stripped and thrown into the well, he called to his brothers to return some clothing to him, pleading with them not to leave him to die naked.16 The brothers callously refused, replying that if Joseph wanted something he should request it of the sun, moon, and stars of his dream.17 Now, relate these sources, when Abraham was thrown into the fiery furnace prepared for him by the evil king Nimrod, he too had been stripped naked. So God sent the angel Gabriel to him to dress him in a shirt. Significantly, this was not just any shirt, but one that was made of the silk of Paradise. Abraham’s son Isaac inherited this shirt when Abraham died, and Jacob inherited it from Isaac when Isaac died. Jacob took the shirt and placed it in an amulet which he then hung around Joseph’s neck.18 When Joseph was thrown naked into the pit, an angel—some say Gabriel, some say this was God Himself—came to him, took the shirt out of the amulet and clothed Joseph in it.19 This was the shirt he was wearing on the trip with the Ishmaelite caravan and this was what he was wearing when he entered Egypt. And this was the shirt, made from the silk of Paradise, which Joseph later sent back to Jacob with instructions to the messenger to place it over his father’s face.20

Importantly, in these accounts, this shirt is said to have had a unique and powerful scent. According to Thaʿlabī, after Joseph sent the shirt-bearing messenger on his way, the wind asked for and received permission from God to bring the scent of Joseph to Jacob before the messenger arrived. However, the wind did not blow on Joseph himself in order to release Joseph’s scent. Rather, Thaʿlabī, Ṭarafī, and Kisāʾī report, the wind shook out Joseph’s shirt and carried that scent to his father.21 Ibn ʿAbbās, as cited by Muḥammad b. Jarīr al-Ṭabarī (d. 310/923), notes that when the caravan left Egypt, the smell of Joseph’s shirt reached Jacob before the shirt itself did, even though it had to travel a distance of about eight days.22 Lest we think that the odor that reached Jacob was the smell of Joseph’s body, embedded in his cloak, Thaʿlabī and Ṭarafī explain that the shirt, created in Paradise, smelled of Paradise.23 Thaʿlabī and Ṭarafī also cite al-Daḥḥak and al-Suddī, who note that the shirt, inherited from Abraham, was woven in Paradise and had the scent of Paradise.24

In comparing the lover’s self-soothing by looking at the clothing of his absent beloved to the image of Jacob’s blindness being cured by the smell of Joseph, Ibn Ḥazm has employed a qiṣaṣ motif. On one level, this should not strike us as a puzzling move. The qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ accounts provide readers with many colorful exegetical and narrative motifs and, since Muslim poets drew from the entire corpus of Islamic literature, more than a few of these appear in Andalusian Arabic poetry. At the same time, however, we must remember that the Qurʾān provides a clear description and sequence of events for this account. Why then does the scholar Ibn Ḥazm choose the qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ version, one which seems to contradict the Qurʾān, over the Qurʾān’s authoritative version? Indeed, Ibn Ḥazm appears to consciously blur the lines between the two corpora regarding this narrative. As he writes in his introduction to this poem, the soul of a man who possesses something of his beloved feels satisfied even if the result is no more than “what God specified for us regarding Jacob’s getting his sight back when he smelled the shirt of Joseph.”25 As noted, only in the qiṣaṣ accounts does Jacob actually smell the shirt.

Our question becomes even more thought-provoking when we realize that the behavior of the poem’s lover does not actually parallel that of the extra-scriptural Jacob to whom he is compared any more than that of the qurʾānic Jacob, to whom he is not. Just as the poem’s lover does not touch his beloved’s clothing (as the Jacob of the Qurʾān does), so too does he not smell his beloved’s clothing (as the Jacob of the qiṣaṣ does). Rather, he simply looks at the abandoned item from a distance, without otherwise engaging it. Nykl’s English translation obscures this important detail and allows the reader to imagine that the lover has in fact snuggled up to the shirt. He translates: “I began to content myself with his dress, / or was contented with something he had touched.”26 However, the Arabic original clearly indicates something that Nykl has omitted: ṣirtu bi-ibṣārī athwābahu aw baʿḍ mā qad massahu aktafī. A more accurate, though less poetic, translation would read: “I contented myself with looking at his clothes or at something that he had touched.” In Ibn Ḥazm’s original, the lover looks, without touching, and without inhaling. Given that the lover does not perform the same act as either the qiṣaṣ Jacob or the qurʾānic Jacob, is there any benefit in Ibn Ḥazm’s comparing him to an image from the former over one from the more authoritative latter?

Indeed there is. The incorporation of the qiṣaṣ reference alone transmits a message about romantic love that is both potent and subversive. In truth, on one level, the linking of the beloved’s qamīṣ to either the qurʾānic or the qiṣaṣ qamīṣ results in the same message: human love is salvific. Just as the cloak of Joseph, in either rendition, cured Jacob of his grief-induced blindness, so the cloak of the beloved will cure the lover of the misery and depression that eats away at the lover’s soul. However, the comparison with the qiṣaṣ image takes this lesson one step further: it implies that the love between humans is not only redemptive but is, at its core, divine. After all, according to the qiṣaṣ, the shirt that miraculously returns Jacob’s sight was created by God in Paradise, woven through with the scent of Paradise, imbued with God’s powers in Paradise, and sent down to humanity by God from Paradise.

In the Qurʾān, by contrast, God plays no outright role in this particular part of the story. In Q 12, Joseph sends his shirt to his father without God’s instruction to do so, and without God’s say-so he tells the messenger that the shirt will perform a healing miracle, one normally attributed to God’s powers alone.27 So too when the miraculous healing takes place (v. 96), the Qurʾān records it with no mention of God. The qiṣaṣ accounts restore God to the narrative through the mechanism of the shirt. In comparing the beloved’s shirt to this shirt, the divine shirt of the qiṣaṣ, the poem’s male lover implies that his male beloved’s shirt too has divinely sanctioned, or divinely given, salvific powers.28

A Qiṣaṣ Image in a Hebrew Poem of Spain

Ibn Ḥazm’s poem is not the only ʿishq poem written by a religious scholar of Andalusia to incorporate the motif of salvation transmitted through the aroma of the beloved’s clothing. Nor does the motif appear only in Arabic poems authored by Muslims. It also appears in a Hebrew poem written by Ibn Ḥazm’s contemporary and one-time friend, the Jewish scholar, military vizier of Granada, and poet Samuel the Nagid.29 In his Diwān, Samuel includes the following poem.30

רעיה, צבי מבור שבי התפתחי ריח בגדיך לבשרו שלחי

הבמי אדמים תמשחי שפתיכי או דם עפרים תמרחי על הלחי

דודים לדוד, תגמול אהביו, תתני רוחי ונשמתי, מקום מהרך, קחי

לב בשתי עיניכי אם תפלחי- באחד ענק מצוארוניך יחי

My love, will you free a gazelle that fell in a pit?

Just send him the scent of your outfit.

Is it red paint that reddens your lips?

Is it fawns’ blood smeared on your cheeks?

Make love to your lover, reward him with love—

Take my spirit and soul as your price.

My heart, pierced by both your eyes, will rise from the dead

With your necklace—or even with one bead!31

Like Ibn Ḥazm’s poem, in many ways this poem follows well the conventions of Andalusian ʿishq poetry. The lover and the beloved are separated from one another as usual, with the continued alienation caused by the beloved herself who, having thrown the lover in a pit, makes no move to extricate him from his captivity.32 The beloved appears with rosy cheeks and rosy lips (line 2) and the lover cannot tell from what: is the beloved innocently wearing lipstick (bi-mei adamim, “red-tinted waters”)? Or has she, in line with the trope of the beloved as cruel and murderous, rouged her face with the blood of conquered lovers? The lover attempts to negotiate his freedom, begging her to send him salvation (line 1) and bartering with his life (another trope, line 3). However, these negotiations appear to fail. Unwilling to be completely defeated, the lover remains stereotypically loyal to his beloved, reassuring himself (and her?) that although all seems lost, it is not the end (line 4); if with one look from her eyes she tears his heart asunder, referencing the trope of the beloved’s dangerous body (and, in particular, the eyes), it will continue to live as one of the beads on her necklace. Tova Rosen has explained this image by suggesting that the lover sees the beloved as a huntress extraordinaire, wearing the hearts of conquered lovers on a chain around her neck as trophies and thus allowing them to remain living, in a sense.33

As in Ibn Ḥazm’s poem, a scriptural reference underlies the Hebrew poem, in good Andalusian form. While it may not be as obvious in the Hebrew as in the Arabic, to those familiar with biblical narratives and biblical vocabulary, the reference leaps off the page in the poem’s third and fourth words, bor sh’vi, the pit of captivity in which the lover languishes. Above this bor stands the one responsible for the captive’s incarceration, one who is smeared with animal blood. For readers of the Bible, the vocabulary choice of bor, as a pit that holds a person captive, with the attacker looming nearby, and smeared animal blood in the visual field, hints loudly at one very famous story, the same one referenced in Ibn Ḥazm’s poem: the account of Joseph and his brothers. Genesis 37 tells of the brothers’ jealousy of the favoritism shown by Jacob for his eleventh son, of their stripping Joseph of his clothes, throwing him into a waterless pit (v. 24), selling him to a passing caravan, smearing his coat with kid’s blood (v. 31), and then allowing their father to believe that a wild animal had killed his beloved child (v. 32–33), after which he grieves inconsolably. Significantly and famously, the word bor, as the pit of Joseph’s captivity, appears six times in eight verses in the Genesis account (37:22–29).

As with Ibn Ḥazm’s identification of the lover with the scriptural hero, in Samuel’s poem the subtle identification of the lover with the captive Joseph, alone and suffering, emphasizes the pathos of the lonely lover’s situation. Both are thrown into a pit by those who should love and protect them the most (brothers and beloved). And in both cases, this cruel treatment is carried out completely unjustly.

While the opening image of the pit’s captive clearly recalls the biblical Joseph in his captivity, the image in the second hemistich, in which the captive calls for a message of redemption to be sent from the beloved’s clothing, seems out of place. It does not belong to the biblical Jacob-Joseph narrative, neither to its beginning nor its end. Indeed, the Bible does record that Jacob and Joseph are eventually reunited and that the reunion provides the previously grief-stricken Jacob with much relief. As Gen 45:27 reports, “And they told him all the words of Joseph, which he had said unto them; and when he saw the wagons which Joseph had sent to carry him, the spirit of Jacob their father revived.”34 Unlike in the Qurʾān, this relief from sorrow and heartache is not caused by any garment of Joseph’s. Rather, Jacob’s spirit is revived by the news that Joseph lives and now rules over Egypt and by the sight of the carriages that Joseph sent to his father to bring him to see his long-lost son (Gen 45:26–27).

The motif of a salvifically scented cloak does not appear to have been one of the more common tropes of Andalusian Hebrew poetry either. This is not to say that scent makes no appearance in these poems, for it does. But as in the biblical Song of Songs from which the Andalusian Hebrew poems frequently draw love imagery, when this motif appears, it is almost always the scent of the beloved him- or herself (rather than his or her clothes) that is under discussion.35

Nor can we attribute this image to the rabbinic tradition. Following the lead of the Bible, no rabbinic text from before the rise of Islam (indeed, no Jewish text I could find) mentions a cloak at all in the account of Joseph revealing himself to Jacob. Rather, Genesis Rabbah (ca. fifth c. CE) and Midrash Tanḥuma (ca. fifth c. CE) both understand that it was the wagons that Joseph sent to his father that revitalized him. 36 Playing on the Hebrew word for wagons, ʿagalot, both texts explain that Jacob recalled that he and Joseph had been studying the biblical text of ʿeglah ʿarufah (the heifer whose neck was broken) when Joseph disappeared, a fact only the two of them would know. 37 Thus, when Jacob saw that Joseph (and not Pharaoh) had sent ʿagalot for him, he understood that Joseph was truly alive and his spirit was revived.38

Only beginning in the eleventh century do we find Jewish narratives that attribute significance to an item of Joseph’s clothing other than the multi-colored tunic which had earlier caused his brothers’ envy and hatred. The accounts are remarkably similar to those in the qiṣaṣ. For example, according to the medieval Midrash ‘Asarah Harugei Malchut39 and to the twelfth/thirteenth century Tosafists preserved in Sefer Hadar Zekeinim, when Joseph was stripped naked and thrown into the pit (Gen 37:23–24), God took pity on him that he not be paraded around in such a state. Now Joseph wore an amulet around his neck, relate these accounts.40 So God sent an angel—in one version Gabriel, in the other Rafael—who drew a cloak out of the amulet, or turned the amulet into a cloak, and dressed Joseph in it.41 The Jewish sources then diverge from the qiṣaṣ accounts that connect this cloak back to Abraham, or attribute its origins to Paradise, or imbue it with healing powers. Instead, these later rabbinic texts maintain that when the brothers drew Joseph up from the pit to hand him over to the Ishmaelites, they could not help but notice that he was somehow now clothed. Oddly, they did not stop to wonder how that happened or what it might mean. Instead, they demanded that the Ishmaelites pay extra for the cloak since, after all, the cloak had not been included in the original bill of sale, only a naked boy.42

Given all of this, it seems possible that the trope of the salvation-bearing-cloak-aroma entered Samuel’s Hebrew poem under the influence of the Muslim Andalusian Arabic poetry-writing milieu. As has been shown here, while the image does appear in the qiṣaṣ literature, it cannot be found in biblical, midrashic, or Andalusian Hebrew poetic literature. Perhaps Samuel knew the image from Ibn Ḥazm’s qiṣaṣ-inflected poem, which utilized the very same scriptural story. Indeed, not only were both men from Cordoba, and only one year apart in age, but they knew one another personally and even considered one another friends for a time. This we know from Ibn Ḥazm’s own testimony in his Fiṣāl fī’l-milal wa’l-ahwāʾ wa’l-niḥal, where he later reports on their first meeting in 404–5/1014 in Malaga, when both were in their early twenties.43 Writing with the perspective of time, Ibn Ḥazm refers to the young man who later became the poet, writer, biblical scholar, philosopher, military vizier of Granada, and leader (a.k.a., the Nagid) of the Jewish community as “the most learned and best polemicist” of the Jews.44 It stands to reason that Samuel the Nagid, who mastered Arabic as well as Hebrew poetry, may have been familiar with Ibn Ḥazm’s poetic treatise Ṭawq al-ḥamāmah, written only a few years after their first meeting. Indeed, David Wasserstein has suggested that Samuel the Nagid and his family may have been far more immersed in Arabic culture than scholarship has previously suspected.45 It seems plausible that the qiṣaṣ trope of a salvifically-scented cloak of Joseph’s entered into the shared Muslim-Jewish cultural space of Muslim Spain where, thanks to the emotional potency of the image, it was employed by ʿishq poets of both religions alike.

Conclusion

While Ibn Ḥazm’s subtle use of the qiṣaṣ rather than qurʾānic material in his poem initially seemed somewhat of a mystery, we now understand better the need for such a move. In drawing a parallel between the cloak of Joseph that heals his father’s blindness and the beloved’s garment that dispels the lover’s anguish, Ibn Ḥazm’s lover teaches his readers a lesson about the power of human love. Namely, for Ibn Ḥazm and his poem’s lover, it is redemptive and salvific. In employing the cloak as depicted in the qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, which emphasize the garment’s paradisiacal origin and nature, Ibn Ḥazm’s poem more sacrilegiously implies that both human loves—that of scriptural father for son and of lover for beloved—are sanctioned and protected by the Divine. Interestingly, so powerful was the qiṣaṣ’ image of the aromatic salvation-bearing cloak that it may have broken through the religious boundary-lines of Islam and Judaism and found a surprising new home in a similarly Joseph-inflected Hebrew poem by Ibn Ḥazm’s Jewish contemporary, Samuel the Nagid.

While Samuel the Nagid employs the parallel biblical account as well as the qiṣaṣ image of a salvation-bearing scented garment, he does so to a different end than does his Muslim counterpart. Significantly, our two poets focus on the diametrically opposite ends of the scriptural tale. As we see, Samuel the Nagid’s poem engages the earlier part of the narrative, when Joseph is first attacked and isolated from his father, and identifies the lover with the suffering and abused son. Ibn Ḥazm’s poem references the latter part of the account, identifying the lover with the mourning father and spotlighting the miraculous moment in which Jacob and his beloved Joseph are joyfully and salvifically reconnected. This dissimilar focus results in differing poetic messages. While Ibn Ḥazm’s poem ends on a note of hope and redemption, the Hebrew poem can lay no such claim to the same. Although the biblical Joseph does eventually find redemption from his pit of despair and reconnects with his beloved father, the Hebrew poem chooses not to focus on this theme. In the Hebrew poem, the scented garment can bring only news, not redemption itself. And even that does not actually happen. Instead, Samuel’s poem dwells on the continued suffering of the lover who even in death remains loyal to his murderous huntress beloved, as any good Andalusian lover must.

About the author

Shari L. Lowin is Professor of Islamic and Jewish Studies in the Religious Studies Department at Stonehill College, where she also directs the Middle East Studies minor. Her research focuses on the interplay between early and classical Islamic exegetical narratives, most notably qiṣaṣ al-anbiyā’ and the rabbinic midrash aggadah materials. Her most recent book, Arabic and Hebrew Love Poems in al-Andalus (London: Routledge, 2014), follows these materials into the Arabic and Hebrew eros poems of Muslim Spain. Lowin is also the editor of the Review of Qur’anic Research.

Notes

1 See Charles Pellat (trans. and ed.), The Life and Works of Jāḥiẓ, trans. from the French by D. M. Hawke (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1969), 263ff.

2 There are many in-depth studies of ʿUdhrite poetry and its influence on Andalusian Arabic poetry. See, e.g., G. E. von Grunebaum (ed.), Arabic Poetry: Theory and Development (Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1973); Arie Schippers, Spanish Hebrew Poetry and the Arabic Literary Tradition: Arabic Themes in Hebrew Andalusian Poetry (Leiden: Brill, 1994); and Salma Jayyusi, “Umayyad Poetry,” in A. F. L. Beeston et al. (eds.), The Cambridge History of Arabic Literature: Arabic Literature to the End of the Umayyad Period (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 387–432. An overview can be found in Shari L. Lowin, Arabic and Hebrew Love Poems in al-Andalus (London: Routledge, 2014), 1–21.

3 Part of the reason behind the Jewish adaption of this practice relates to the ʿarabiyyah-shuʿūbiyyah controversy of medieval Spain. For an overview, see Lowin, Arabic and Hebrew Love Poems, 11–13. More in-depth discussions can be found in Nehemiah Allony, “The Reaction of Moses Ibn Ezra to ʿArabiyya,” Bulletin of the Institute of Jewish Studies 3 (1975): 19–40 and Norman Roth, “Jewish Reactions to the ʿArabiyya and the Renaissance of Hebrew in Spain,” Journal of Semitic Studies 28 (1983): 63–84.

4 Ross Brann, “How Can My Heart Be in the East? Intertextual Irony in Judah Ha-Levi,” in B. H. Hary, J. L. Hayes, and F. Astren (eds.), Judaism and Islam: Boundaries, Communication, and Interaction (Leiden: Brill, 2000), 365–380, 374.

5 Biographies of Ibn Ḥazm abound. One impressive recent in-depth collection of articles about him is Camilla Adang, Maribel Fierro, and Sabine Schmidtke (eds.), Ibn Ḥazm of Cordoba: The Life and Works of a Controversial Thinker (Leiden: Brill, 2013). Camilla Adang has authored numerous articles on different aspects of Ibn Ḥazm’s life and scholarly oeuvre, including in the just-mentioned volume. Some scholars have maintained that the Ẓāhiri school was never that important to Islamic theology in general or in Andalusia in particular. In discussing Ibn Ḥazm’s ejection from the Great Mosque in Cordoba, Adang suggests otherwise. See her “Restoring the Prophetic Authority, Rejecting Taqlid: Ibn Ḥazm’s ‘Epistle to the One Who Shouts from Afar,’” in Daphna Ephrat and Meir Hatina (eds.), Religious Knowledge, Authority and Charisma: Islamic and Jewish Perspectives (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2014), 50–63. See also Adang, “Ẓāhirīs of Almohad Times,” in María Luisa Ávila and Maribel Fierro (eds.), Biografías Almohades II (Madrid-Granada: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 2000), 413–479.

6 Abū Muḥammad ʿAlī b. Ḥazm al-Andalusī, Tauḳ al-ḥamâma, ed. D. K. Pétrof (St. Petersburg and Leiden: Brill, 1914), 90.

7 The accuracy of the translation of this line will be discussed further on.

8 Meaning, a prophet rightly guided by God.

9 Although Nykl translates this with the definite article (“the tunic”), the literal translation of the Arabic is “a tunic.” See the next note.

10 The English translation is largely by A. R. Nykl, in his A Book Containing the Risāla Known as the Dove’s Neck Ring about Love and Lovers Composed by Abū Muḥammad ʿAlī ibn Ḥazm al-Andalusī (Paris: Libraire Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, 1931), 138–139. While Nykl’s translations refer to the beloved in the feminine form (“mistress” “she,” “her”), the Arabic consistently presents the beloved in the masculine (e.g., سيّدي” ,” sayyidī, “my master”). Early scholars and translators often tried to avoid admitting that the religious poets of Islamic and Jewish Andalusia wrote poems to male beloveds, and the translators were known to shift the beloved’s gender in their translations. Sometimes the claim was made that the poets intended a female beloved but used the male pronoun out of modesty concerns, a valid explanation in some cases, but not all. See Charles Pellat, “Liwāṭ,” in Arno Schmitt and Jehoeda Sofer (eds.), Sexuality and Eroticism among Males in Moslem Societies (New York: The Haworth Press, 1992), 151-168. 157. I have altered the translation to reflect the Arabic use of the masculine.

11 In one Arabic poem, a female beloved accuses her lover of lying about his love for her because he has enough strength to declare his love to her. A true lover, she scolds, would be too sick to do so. See Raymond Scheindlin, “Ibn Gabirol’s Religious Poetry and Sufi Poetry,” Sefarad 54 (1994): 109–141, 113–114.

12 See Schippers, Spanish Hebrew Poetry and the Arabic Literary Tradition, 169.

13 As noted above, the use of a masculine pronoun to refer to the beloved does not always indicate a male beloved; Andalusian poets did sometimes employ the masculine when referring to a female. In our case, however, there is nothing in the poem or in the text that precedes or follows it that indicates we should read the beloved as female. In fact, the very next love story that Ibn Ḥazm relates concerns a same-sex male couple, a situation reflected in the accompanying poem. Thus we see that not all of Ibn Ḥazm’s male beloveds should be read as female. Indeed, Adang has argued convincingly that while Ibn Ḥazm remained unfailingly against actualized homoerotic sexual contact, he was not averse to recognizing and speaking positively of emotional attachment and even sexual attraction between men. See Camilla Adang, “Love between Men in Ṭawq al-Ḥamāma,” in Cristina de la Puente (ed.), Identidades Marginales (Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 2003), 111–145.

14 Although the Qurʾān does not state so outright, it is obvious that the meaning here is that Joseph and “his brother” come from the same mother while the rest of the brothers are half-brothers, as recorded in Genesis 29–30, 35:22-26.

15 While the Bible does not describe Jacob as blind or Joseph as having healed him, John Macdonald suggests that Gen 46:4 may be the source for this qurʾānic element. In this verse, God tells Jacob in a dream that “Joseph will place his hand upon your eyes.” See John Macdonald, “Joseph in the Qur’ān and Muslim Commentary,” Muslim World 46 (1956): 113–131, 207–224. While this in an interesting hypothesis, the connection between the two would be stronger if one could point to a pre-Islamic reading of Gen 46:4 that teaches something along those lines. Macdonald does not. Additionally, if any biblical element can be said to have influenced the qurʾānic motif of Jacob’s blindness and Joseph’s curing him, it seems more likely to be found in the story of Isaac. Gen 27:1 relates that in his old age, Isaac went blind. Jacob (and his mother Rachel) took advantage of this in order to trick Isaac into giving Jacob the blessing of the elder son (Jacob was the younger). When Jacob, dressed as Esau, entered his father’s presence, Isaac was unsure which son stood before him; the man’s voice sounded like Jacob’s but his arms were hairy like Esau’s. In verse 26, Isaac asks his son to step forward and then sniffs him. Recognizing the scent as that of the outdoorsy Esau, Isaac determines that the son before him is the “correct” one—Esau—and blesses him with the first-born’s blessing (v. 27ff). Like the qurʾānic Joseph whose shirt and its scent restored his father’s sight, the scent of Isaac’s son thus restored Isaac’s sight, though in this case “sight” is metaphorical rather than physical.

16 See Aḥmad b. Muḥammad al-Thaʿlabī, Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ al-musammā ʿArā’is al-majālis, (Egypt: Muṣṭafā al-Bābī al-Ḥalabī, 1374/1954), 79–80; Muḥammad b. ʿAbd Allāh al-Kisāʾī, Vita Prophetarum auctore Muhammad ben Abdallah al-Kisa’i, ed. Isaac Eisenberg (Leiden: Brill, 1923), 158–159; Ibn Muṭarrif al-Ṭarafī, The Stories of the Prophets by Ibn Muṭarrif al-Ṭarafī, ed. Roberto Tottoli (Berlin: Klaus Schwarz Verlag, 2003), 99, no. 265 and 121, no. 319. This account is also found in the commentary of al-Bayḍāwī (d. 685/1286). See ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿUmar al-Bayḍāwī, Tafsīr al-Bayḍāwī (Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyyah, 1988), ad 12:15 (1.478) and 93 (1.495). In a slightly earlier pericope, Thaʿlabī maintains that Joseph’s shirt, the one stripped off him by his brothers, had been passed down from Adam, who had received it in the garden of Eden. When the brothers brought it to Jacob, after dipping it in animal blood, Jacob recognized it. See Thaʿlabī, Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, 79. For more on Adam’s garment, see Stephen D. Ricks, “The Garment of Adam in Jewish, Muslim, and Christian Tradition,” in Hary et al, Judaism and Islam, 203–225.

17 Q 12:4.

18 According to Thaʿlabī (Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, 79) and Ṭarafī (Stories of the Prophets, 121, no. 319), Jacob did so to protect Joseph from the evil eye. We find a subtle reference to this story in the tafsīr of Ibn ʿAbbās which, while not preserving the entire narrative, does explain that the shirt that Joseph sent to Jacob was from Paradise. See Muḥammad b. Yaʿqūb al-Fīrūzabādī, Tanwīr al-miqbās min tafsīr Ibn ʿAbbās (Egypt: Muṣṭafā al-Bābī al-Ḥalabī, 1370/1951), 153. While some maintain that this text was written by Ibn ʿAbbās (d. ca. 68/687–688) and others by al-Fīrūzabādī (d. 817/1414), Andrew Rippin argues that the more likely author is al-Dīnawarī (d. 308/920). See Andrew Rippin, “Tafsīr Ibn ʿAbbās and Criteria for Dating Tafsīr Texts,” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 18 (1994): 38–83. Others disagree. For example, Josef van Ess maintains that the text, of undetermined date and authorship, dates to before the end of the ninth century. See his Theologie und Gesellschaft im 2. und 3. Jahrhundert des Hidschra: Eine Geschichte des religiösen Denkens im frühen Islam (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1995), 1.300–302. See also Harald Motzki, “Dating the So-Called Tafsir Ibn ʿAbbas: Some Additional Remarks,” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 31 (2006): 147–163.

19 The handing down of artifacts from prophet to prophet as a testament of prophetic succession appears not infrequently in the Islamic tradition. The most famous example concerns ʿAlī’s sword Dhū’l-Faqār, said to have been brought from Paradise by Adam and handed down through all the prophets to Muḥammad, then to ʿAlī. On this and other such traditions, see Uri Rubin, “Prophets and Progenitors in the Early Shī’a Tradition,” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 1 (1979): 41–65. Majid Daneshgar has undertaken a more recent and quite varied study of the traditions relating to ʿAlī’s sword in his “A Sword That Becomes a Word (Part One): Supplication to ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib and Dhū’l-Faqār,” Mizan, January 9, 2017 and “A Sword That Becomes a Word (Part Two): The Supplication to ʿAlī in a Malay Manuscript,” Mizan, February 8, 2017.

20 According to Ṭarafī (Stories of the Prophets, 121–122, no. 319), Joseph did this on Gabriel’s advice. The qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ and the tafsīr texts do not stand in complete agreement regarding the number of shirts involved in the Joseph narrative. For example, Bayḍāwī (1.478 ad Q 12:15) remains uncertain as to whether the shirt Joseph sent to Jacob was the shirt he was then wearing or was the one that had been in the amulet.

21 Thaʿlabī, Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, 135–138; Kisāʾī, Vita Prophetarum, 176. See also ʿAbd al-Razzāq al-Ṣanʿanī (d. 211/827), Tafsīr al-Qur’ān, ed. Muṣṭafā Muslim Muḥammad (Riyadh: Maktabat al-Rushd, 1989), 1.2.329 and Bayḍāwī, Tafsīr, 1.495 ad Q 12:94. Ṭarafī notes that the shirt smelled of Paradise but he does not state that the wind asked for shaking-out-smell permission (Stories of the Prophets, 121–122, no. 319). While the wind’s request is recorded by Ṭabarī, he does not mention that the wind shook the cloak. Rather, in this version, the wind seems to simply blow Joseph’s odor, without specifying if it came from Joseph himself or from his clothing. See Muḥammad b. Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, Taʾrīkh al-rusul wa’l-mulūk, ed. M. J. de Goeje (Leiden: Brill, 1879-1901), 1.407–409.

22 See Ṭabarī, Jāmiʿ al-bayān ʿan taʾwīl āy al-Qurʾān (Egypt: Muṣṭafā al-Bābī al-Ḥalabī, 1373/1954), 13.57-58 ad Q 12:94. Note that Ṭabarī here cites numerous ḥadīth reports, all traced back to Ibn ʿAbbās.

23 Thaʿlabī, Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, 138.

24 Combining touch and smell, these commentators also note that when this paradisaically-scented garment touched an ailing or afflicted person, they would be restored to health. See Thaʿlabī, Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, 96 and Ṭarafī, Stories of the Prophets, 121, no. 319. Kisāʾī (Vita Prophetarum, 156–157) records five miraculous items that Joseph inherited from Abraham: the turban of prophethood, the coat of friendship, the girdle of victory and contentment, the ring of prophethood, and the staff of light. The theme of the paradisiacal shirt which clothed Joseph in the pit and then healed Jacob’s blindness appears to have taken hold in the Muslim popular imagination as well, for we find it in an anonymous Egyptian thirteenth- or fourteenth-century Arabic poetic rendition of the Joseph story. See R. Y. Ebied and M. J. L. Young (eds. and trans.), The Story of Joseph in Arabic Verse (Leiden: Brill, 1975), lines 152ff. and 419ff.

25 ما نصّ الله تعالى علينا من ارتداد يعقوب بصيرًا حين شمّ قميص يوسف (Pétrof, Tauḳ al-ḥamâma, 90).

26 See above, note 10.

27 As Jesus reports in Q Ᾱl ʿImrān 3:49, although he will heal the sick he will do so only with God’s permission.

28 In his What is Islam?, Shahab Ahmed discusses whether the theme of erotic love, present in Sufi poetry and prose as well as in other genres of Islamic literature, is in fact “Islamic.” Ahmed maintains (46) that the “self-evident historical commonplaceness and centrality of the madhhab-i ʿishq at the heart of the mainstream” of Muslim practices, discourses, and “self-constructions” shows that it is. See Ahmed, What is Islam? The Importance of Being Islamic (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016), esp. 32–46.

29 For more on Samuel the Nagid’s life and biography, see A. M. Habermann, “Samuel Ha-Nagid,” in Encyclopaedia Judaica (New York: Keter, 1972), s.v.

30 Dov Jarden (ed.), Divan Shmuel ha-Nagid. Ben Tehillim (Jerusalem: Hebrew Union College Press, 1966), 297, no. 161. Ḥaim Schirmann presents a slightly different version of line 3, which barely changes the meaning: דודים לדודך תגמול אהביו תני—רוחי ונשמתי מקום מהרך קחי. See his Ha-Shira ha-’Ivrit be-Sefarad u-be-Provens (Jerusalem: Mossad Bialik, 1954), 1.153, no. 4.

31 Translation by Tova Rosen in her Unveiling Eve: Reading Gender in Medieval Hebrew Literature (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003), 40. The fourth line is difficult in Hebrew, as it is in English. See the following paragraph for an explication.

32 Unlike in Ibn Ḥazm’s poem, the beloved here is clearly identified as female. The first word, רעיה (raʿeyah, “beloved”), by which the poet addresses the beloved directly, is the feminine form. All the subsequent verbs that speak of the beloved’s behavior are likewise addressed to the second person feminine.

33 Tova Rosen, Tzed ha-Tzviyyah: Qeriyah Migdarit be-Safrut ha-ʿIvrit mi-Yimei ha-Beinayim (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University Press, 2006), 60.

34 Midrashic sources express rabbinic discomfort with this biblical line. What does it mean to say that Jacob’s spirit was revived when, they point out, he hadn’t been dead? According to Midrash Tanḥuma (ca. fifth c. CE), Pirqei de-Rabbi Eliezer (ca. eighth c. CE), and Targum Pseudo-Jonathan (ca. seventh-eighth c. CE), the verse means that the spirit of prophecy returned to him. Jacob had lost it when his sons banded together to take an oath to conceal from him what had happened to Joseph, on pain of excommunication, and had included God in the oath-ban as well. (The inclusion of God in the ban explains why God kept Jacob in the dark all these years.) See Midrash Tanḥuma (Jerusalem: Hotsa’at Levin-Epstein, 5729 [1968/9]), Vayeshev 2; Pirqei de-Rabbi Eliezer (Jerusalem: Eshkol, 5733 [1973], ch. 38; and Targum Pseudo-Jonathan, trans., annotation, and intro. Michael Maher (T & T Clark: Edinburgh, 1992) ad Gen 45:27.

35 Two exceptions to this rule do appear in the Song of Songs. Song 4:11 relates: “Thy lips, O my bride, drop honey—honey and milk are under thy tongue; and the smell of thy garments is like the smell of Lebanon.” Psalm 45:9 also mentions scented garments: “Myrrh, and aloes, and cassia are all thy garments; out of ivory palaces stringed instruments have made thee glad.” Unlike in the poem, these are not smells that deliver messages.

36 The dates of these midrashic texts and those that follow refer to the conventional dates of final redaction. The midrashic texts tend to include much earlier materials but the compilations themselves remained open to changes for centuries.

37 Deuteronomy 21:1–9

38 Targum Pseudo-Jonathan (46:17) offers a cryptic alternative to how Jacob learned the truth. According to this text, Seraḥ, the daughter of Asher, gently delivered the news to her father, for which she was rewarded by entering into Paradise alive. A later text developed in order to flesh out the details. According to Sefer ha-Yashar, Joseph and his brothers worried that the startling news regarding Joseph might shock Jacob to death. So the brothers commissioned Seraḥ the daughter of Asher to play a lyre before her grandfather and sing gently to him, “Joseph my uncle did not die, he lives and rules all the land of Egypt.” When Jacob sensed the truth of her words, joy filled his heart and the spirit of God rested on him. See Sefer ha-Yashar ‘al ha-Torah (Berlin: Binyamin Hertz, 1923), Vayigash 14. While this text is often said to date to the eleventh or twelfth century, Joseph Dan sees it as much later, composed only in the beginning of the sixteenth century. See H. L. Strack and Günter Stemberger (eds.), Introduction to the Talmud and Midrash, trans. Markus Bockmuehl (2nd ed.; Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1996), 339–340; Joseph Dan, Ha-Sippur ha-ʿIvri bi-Yemei ha-Benayim: ʿIyyunim be-Toldotav (Jerusalem: Keter, 1974), 137f.; and the introduction to Sefer ha-Yashar, ed. Joseph Dan (Jerusalem: Mossad Bialik, 1986).

There is one pre-Islamic midrash that speaks of a smell wafting from a patriarch’s clothing. In a discussion of Gen 27, Genesis Rabbah tries to explain how it was that when Isaac smelled the clothes worn by a younger Jacob impersonating his hunter brother Esau, he blessed him rather than vomiting from the stench of goat. A tradition found in Genesis Rabbah maintains that Jacob himself smelled like Paradise and this aroma overtook the nastier animal odor. Esau, by contrast, smelled like Gehenna. See Midrash Rabbah ha-Mevo’ar (Jerusalem: Mechon ha-Midrash ha-Mevo’ar, 5744 [1983]), Bereshit [Genesis] 65:22. This does not present a convincing source for our poem’s salvifically-scented cloak. First of all, the odor here belongs to the wrong patriarch (Jacob, not Joseph). Secondly, unlike in Joseph’s case, Jacob’s clothing smells awful; the paradisiacal scent comes from Jacob himself. Thirdly, unlike in the poem, no one is held captive in this biblical account and thus neither aroma (neither of Jacob nor of his clothes) sends forth any messages, let alone messages of salvation or healing. Indeed, the blind Isaac remains blind.

39 Also known as Midrash Eleh Ezkerah.

40 The accounts do not explain why the brothers allow the naked Joseph to hold on to this necklace.

41 In the qiṣaṣ, Joseph’s amulet and the cloak contained in it come from Abraham, who received it from God. The idea of a miraculous necklace worn by a forefather appears also in a much earlier Jewish source, the Babylonian Talmud (ca. sixth c. CE). In Baba Batra 16b, Rabbi Shimʿon bar Yoḥai teaches that Abraham had a precious gem that he wore on a necklace around his neck; whenever a sick person would look upon it, they would be immediately healed. When Abraham died, God suspended the stone in the orb of the sun. Unlike in the qiṣaṣ and in the medieval Jewish texts, the Talmud does not understand this necklace as capable of containing a garment, nor does it trace Joseph’s necklace back to Abraham.

The idea of a protective amulet appears in a fascinating midrashic account regarding Joseph’s eventual wife, Asenath the daughter of Potiphar (Gen 41:45). The rabbis were troubled by the idea that the righteous Joseph would marry and father children with the non-Israelite daughter of a pagan Egyptian. Thus, according to the ca. eighth century Pirqei de-Rabbi Eliezer, Asenath was actually the daughter of Jacob’s daughter Dinah, conceived as a result of Dinah’s rape by Shechem (Gen 34). When Asenath was born, her mother’s brothers wanted to kill her because they feared the shame she, the product of sexual impropriety, would bring the family. Jacob took a gold tag, wrote the name of God on it, hung it around Asenath’s neck and sent her on her way. Now, this was all part of God’s plan, says the midrash, and so the angel Michael descended and led Asenath to Egypt to the house of Potiphar, who raised her. When Joseph later came to Egypt, he married her. See Pirqei de-Rabbi Eliezer, ch. 38. The idea that Asenath was born to Dinah but was raised by Potiphar appears in Targum Pseudo-Jonathan on Gen 41:45.

42 Midrash ‘Asarah Harugei Malchut, in Adolph Jellinek (ed.), Bet ha-Midrasch (Jerusalem: Bamberger and Wahrmann, 1938), 6.20; Sefer Hadar Zeqeinim (Livorno, 5700 [1939–1940]; reprint, Jerusalem: 5723 [1962]), 16b–17a. The ca. eleventh century Song of Songs Rabbah relates that when Joseph was sold, the scent of his clothes spread out all along the road to Egypt and throughout Egypt such that the daughters of the kings would come out to see him. See Midrasch Schir ha-Schirim, ed. L. Grünhut (Jerusalem, 5657 [1897]), parasha aleph, 3.

43 Ibn Ḥazm would have been nineteen or twenty, and Samuel a year older.

44 As cited by José Miguel Puerta Vílchez in his “Abū Muḥammad ʿAlī ibn Ḥazm: A Biographical Sketch,” in Adang et al. (eds.), Ibn Ḥazm of Cordoba, 1–24, 8. According to Ibn Ḥazm, at this meeting, they engaged in a polemic about the accuracy of the Bible. Later in life, Ibn Ḥazm penned a vitriolic text basically attacking Samuel in response for a work he believed Samuel wrote attacking the Qurʾān. Sarah Stroumsa has shown that Samuel was not the author of this text, which was really a compilation of quotations from the Kitāb al-Dāmigh by the ninth-century Muslim heretic Ibn al-Rāwandi. See Stroumsa, “From Muslim Heresy to Jewish-Muslim Poetics: Ibn al-Rāwandi’s Kitāb al-Dāmigh,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 107 (1987): 767–772. See also Theodore Pulcini, Exegesis as Polemical Discourse: Ibn Ḥazm on Jewish and Christian Scriptures (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1998).

45 See David J. Wasserstein, “Samuel ibn Naghrīla and Islamic Historiography in al-Andalus,” Al-Qanṭara 14 (1993): 109–125, esp. 121.

The Cloak of Joseph

A Qiṣaṣ al-Anbiyāʾ Image in an Arabic and a Hebrew Poem of Desire

Introduction

When one studies the “stories of the prophets” in Islamic tradition, one usually looks for them in their expected milieu, the exegetical literature or the collections of qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ materials. However, religious literature relating to the interpretation of the Qurʾān is not the only setting in which such narratives appear. Rather, as we will see, such accounts and their attendant imagery were so entrenched in Islamic society, in Muslim Andalusia in particular, that we find qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ materials appearing even in secular poems of desire, in which they are used to subversive ends. Perhaps more surprisingly, in one case an Islamic qiṣaṣ motif has slipped across confessional bounds and asserted itself in a secular Hebrew desire poem by a Spanish Jewish poet. Such is the situation regarding the motif of the cloak of the forefather Joseph and its startling appearance in both a homoerotic poem by the Ẓāhirī scholar Abū Muḥammad ʿAlī b. Aḥmad b. Saʿīd b. Ḥazm (384–456/994–1064) and in a heteroerotic poem by the Jewish scholar, general, and statesman, Samuel the Nagid (also known as Samuel b. Naghrela, 993–1055/6).

ʿIshq poetry in medieval Spain

The poems of both Ibn Ḥazm and Samuel the Nagid belong to a genre of secular poetry hailing from Islamic Spain known in Arabic as poems of ʿishq and in Hebrew as shirat ḥesheq. In such poems, the poet speaks as a human being engaged in a passionate relationship with another human being. In truth, they are poems of desire rather than of romantic love. This distinction between types of love can be found in the work of earlier Muslim scholars. For example, the litterateur, prose writer, and theologian Abū ʿUthman ʿAmr b. Baḥr al-Kinānī al-Baṣrī, known as al-Jāḥiẓ (d. 155/868), differentiated between ʿishq and another category of love with which it is sometimes incorrectly confused, ḥubb. Jāḥiẓ explains ḥubb as sentimental love, the type of love one feels for one’s family, or for God. While ḥubb constitutes the first stage of ʿishq, he writes, ʿishq requires both a sense of hawā (passion) and a physical component, sexual attraction. While ḥubb lacks the sexual component, sex constitutes the very defining characteristic of ʿishq.1 Sexuality and eroticism stand as key components of ʿishq poems as well.

While this category of poetry attained great heights in Muslim Spain, it was not wholly invented there. Rather, Andalusian ʿishq poems drew from eastern Arabic forms that predated it, mainly ʿUdhrite love poetry, named for the South Arabian tribe from which many of the earliest poets in this genre came. In the pre-Islamic era, love poetry was not an entirely independent poetic form, but rather appeared usually as part of the long ode-like qaṣīdah. These long mono-rhymed poems of often elaborate meter valorized the concerns and ideals of the pre-Islamic Bedouin society in which they developed. The poems celebrated and praised Arab bravery in war, Arab generosity, and frequently described battlefield or pastoral scenes. Love lyrics appeared as the nasīb, the amatory prelude to the poems. With the Islamic conquests and the Islamization of the Arabian Peninsula, especially under the Umayyad caliphate, the poems underwent Islamization as well; Islamic values replaced the pagan standards, and an urban focus replaced pastoral scenarios. Love poems that incorporated the themes of ʿUdhrite love then developed independently of the long qaṣīdah.

The Andalusian form of these love poems reflect many of the values visible in ʿUdhrite predecessors. Known also as pessimistic love poetry or chaste love poetry, ʿUdhrite love poetry presents readers with a highly conventionalized form that frequently speaks of lovers yearning for union with the beloved without any real hope of physical realization. The poems describe the beloved in physical terms, describing the body rather than the character. The beloveds’ bodies themselves are also presented in conventionalized terminology—dark-haired, dark-eyed, with a shape that resembles a date-palm—so that it can sometimes seem there is but one beloved behind a great majority of the poems. The poems speak of the horrific suffering inflicted on the lover by their forced separation from the beloved, and of the cruelty of the beloved who knows of the lover’s suffering but seems either uninterested in alleviating it or actively interested in extending it. Due to this cruelty or apathy, the beloveds’ bodies are also often described as weapons causing grave pain to the lover both up close and at a distance: fingers stab, eyes ensnare, breasts poke like arrows, sprouting beards prick like thorns.2 In adapting ʿUdhrite poems, the Andalusian love poets—both Muslim and Jewish—preserve many of these conventions. However, in at least two ways, Andalusian poets were not quite as forlorn as their ʿUdhrite predecessors. While they suffered in their beloved’s absence, the poets from Spain often sound as if they are recalling actualized physical intimacy which they hoped to re-create or, in some cases, as if they were describing an episode of physical intimacy as it unfolded. Additionally, ʿUdhrite poets were apt to die from their love-suffering; Andalusian poets met their deaths far less often.

Perhaps somewhat surprisingly given the sexualized nature of ʿishq poetry, qurʾānic imagery and storylines not infrequently find their way into the Arabic poems. Such religious references form an updated version of a pre-Islamic convention in which pre-Islamic Arabic poets incorporated figures and themes from Arabic literary tradition and history into their poems. When secular poetry writing came to Islamic Spain, the Muslim poets added or replaced these with qurʾānic and Islamic historical or religious figures. When Andalusian Jews began writing Hebrew poetry on the same model, they replaced the Muslim imagery with allusions to the Bible and midrash.3 For both the pre-Islamic and the Andalusian Muslim poets, incorporating such figures and story-lines into their desire poems was also a way of playing with their audiences. As Ross Brann writes, both Muslim and Jewish poets incorporated sacred imagery and language into their secular poems in order “to create the false impression of irreverence, and thereby entertain the audience (or reader).”4

What is particularly interesting about this irreverent use of scripture is that it appears especially frequently in the secular desire poems of religious authority figures, men otherwise the most concerned with upholding the sacredness of religion and in promulgating its ideals and values. Thus, when such scholars of religion plunder their sacred texts in order to flesh out their heterosexually- and homosexually-charged desire poems, it begs our further attention, for in many cases, these scholar-poets use scripture as more than just poetic ornamentation. As we will see in one short example by Ibn Ḥazm, qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ referents can sometimes serve to sacralize what is an otherwise scandalous romantic attachment.

Ibn Ḥazm and the Cloak of Joseph

Abū Muḥammad ʿAlī b. Aḥmad b. Ḥazm (385–456/994–1064) hailed from a wealthy and learned Cordoban family who trained him in all the arts important to a well-educated medieval Spanish Muslim. He studied Arabic grammar, literature, lexicography, and rhetoric, as well as qurʾānic exegesis, theology, and fiqh (jurisprudence). Ibn Ḥazm grew to be an illustrious theologian, educator, legal authority, and poet. He wrote treatises on Islamic law, on ḥadīth, and even on other religious traditions, though the latter were mostly attacks against these faiths. Eventually, Ibn Ḥazm rose to head the Andalusian Ẓāhiri madhhab, which focused on a literalist reading of the Qurʾān.5

Well before his shift to Ẓāhirism, sometime around the year 414–415/1024, when he was in his late twenties, Ibn Ḥazm composed a thirty-chapter treatise on human love known as Ṭawq al-ḥamāmah (The Dove’s Neck-Ring). In this treatise, Ibn Ḥazm discusses the nature, causes, and aspects of love, behaviors in which lovers engage, and misfortunes that befall human lovers. He often illustrates these principles, which he discusses in prose form, with poetic compositions of his own creation.

In the chapter entitled “On Contentment” (al-qunūʾ), Ibn Ḥazm discusses the behavior of lovers who, separated from their beloveds, seek contentment in the physical objects that had once been in contact with them. In order to illustrate this point, Ibn Ḥazm cites a poem he himself composed. In this poem, he incorporates an example of such contentment-seeking by lovers, an example provided by God Himself.6

لمّا مُنعت القرب من سيّدي

ولجّ في هجري ولم ينصف

صرت بابصاري اثوابه

او بعض ما قد مسّه اكتفي

كذاك يعقوب نبي الهدى

اذ شفّه الحزن على يوسف

شمّ قميصًا جاء من عنده

وكان مكفوفًا فمنه شُفي

When I was prevented from being near to my master

and he insisted on avoiding me and did not treat me justly,

I began to content myself with his dress,7

or was contented with something he had touched;

Thus Jacob, the prophet of true guidance,8

when the grief for Joseph caused him suffering,

smelled the tunic9 which came from him,

and he was blind and from it got well.10

This touching poem conforms to the accepted styles and tropes of Andalusian ʿishq poetry in numerous ways. Most obviously, the poem opens with the tragic tale of two lovers who, in typical Andalusian fashion, are prevented from actualizing their union with one another. While the lover suffers from this enforced alienation, as a good Andalusian lover should, the beloved sadistically worsens his pain by avoiding him and generally treating him with unjust and unearned cruelty (line 2). Such cruel behavior is not particular to this poem’s beloved; rather, Andalusian beloveds were well-known for their harsh reactions to their lovers’ anguish. Despite such cruelty, the poem’s lover remains faithful to his beloved (lines 3–4), embodying yet another well-known Andalusian trope. For the Andalusians, if a lover even appeared to be able to move on from his declared beloved, he might be accused of never having been in love in the first place.11

Passion for the missing beloved usually resulted in physical pain on the part of Andalusian lovers. Their hearts burned, their insides were set aflame, they grew violently ill with grief and passion, they lost so much weight that, as Naṣr b. Aḥmad wrote, a ring that used to be too small for the lover’s finger now serves as his belt.12 Although Ibn Ḥazm’s lover does not mention his anguish outright, in comparing himself to Jacob—famously blinded by grief over his missing son Joseph—the lover drives home this point effectively.

While the use of religious heroes and storylines in secular poetry was not unusual, as already discussed, we ought to take note of the fact that here Ibn Ḥazm draws a comparison between a same-sex couple and two prophetic scriptural characters who are not only not erotically entangled with one another, but are father and son.13 In order to understand the full effect of this scriptural reference, let us briefly review the narrative of Jacob and Joseph as it appears in Sūrah 12 of the Qurʾān, Sūrat Yūsuf.

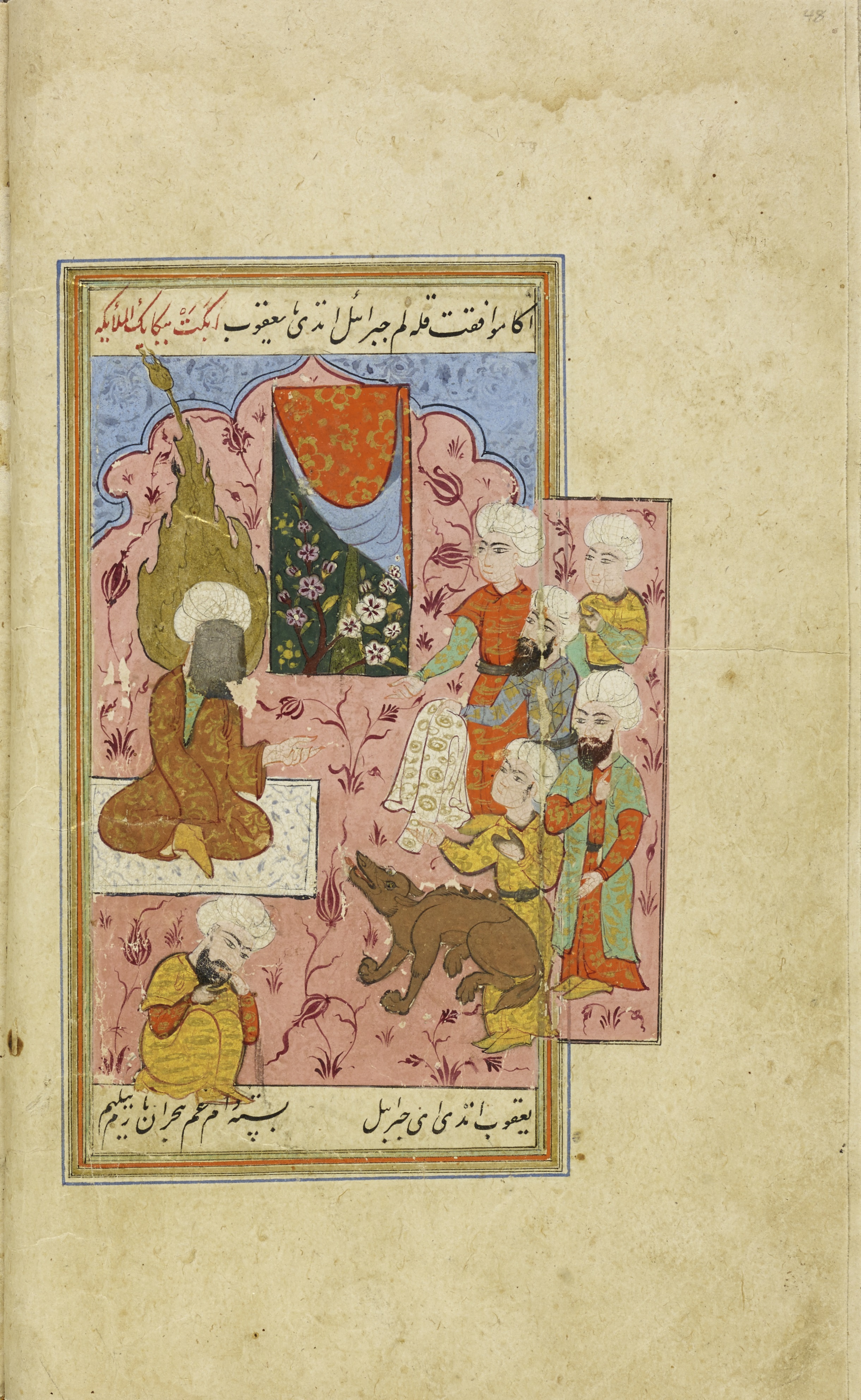

According to this “most beautiful of stories” (Q Yūsuf 12:3), the sons of the prophet Jacob grow jealous of the favoritism their father shows to their brother Joseph and “his brother,” and so they conspire to rid themselves of Joseph.14 They grab him, throw him into a well, and dip his shirt (qamīṣ), which they had apparently stripped from him, into “false blood,” thereby manipulating their father into thinking Joseph has been eaten by a wolf (see Gallery Image A). Joseph is then picked up by a caravan; sold to a man in Egypt; accused of raping the man’s wife; exonerated; brought before the town’s women to show off his beauty; sent to jail, where he meets some jailed dreamers; tells their future; interprets the king’s dream; gets out of jail; and eventually rises to become vizier in Egypt, in charge of the store-houses. Famine strikes Joseph’s homeland and his brothers are forced to come to Egypt in search of sustenance. Because they do not recognize him, Joseph manages to play with them sadistically for a bit (first he accuses them of being thieves, and then holds one of the brothers hostage until his “stolen” item is returned).

In the meantime, Jacob, back at home, has never ceased grieving for his lost son whom he does not believe is dead. His incessant crying for Joseph ultimately leads him to go blind (v. 84). Back in Egypt, Joseph eventually reveals himself to Jacob’s sons as their missing brother, and arranges to send word to his father that he is still alive. He sends Jacob his shirt (qamīṣ) with instructions to the messenger to place it over Jacob’s eyes, saying, “He [Jacob] will regain [his] sight” (v. 93, yaʾti baṣīr). As soon as the caravan leaves Egypt, Jacob—back home—announces that although his sons may once again accuse him of being a fool, he has suddenly detected Joseph’s scent wafting toward him (v. 94). The “bearer of good news” subsequently arrives and casts the shirt over Jacob’s face, and Jacob miraculously regains his sight (v. 96).15 The family then travels en masse to Egypt and father and son are joyfully reunited (v. 97–100).

As we can see, the overall themes of this qurʾānic account dovetail quite nicely with the themes of our Andalusian ʿishq poem. In both we find a moving tale of love between two people who are separated by forces beyond their control. We hear of the pathos of yearning and of the suffering caused by such unrealized love. We learn of the healing caused by not forgetting the missed beloved, of the redemptive value of loyalty. Thus, at first glance, Ibn Ḥazm’s use of this seemingly inappropriate scriptural referent (Jacob and Joseph are father and son and not ʿishq lovers, after all) appears to serve as a good illustration of the greater point he is trying to make about lovers, their faithfulness, and the methods they employ to soothe themselves in their moments of despair and distress.

Yet, if we look carefully at both the poem and the scriptural account, we notice that the poem’s presentation of the Jacob-Joseph narrative deviates in one small but very important way from the Qurʾān’s version. According to the poem, Jacob’s grief-induced blindness is cured when he smells the tunic that came from Joseph (shamma qamīṣ). However, this is not what we find in the Qurʾān itself.

In the Qurʾān, smelling and vision-restoration constitute two separate miracles, one leading up to the other but not actually causing it. The olfactory miracle occurs in verse 94, where as soon as Joseph’s caravan sets out from Egypt, Jacob suddenly detects the aroma of his long-lost son wafting toward him. While the aroma confirms to Jacob what he has believed all along (v. 17–18), that Joseph is not dead, it does not actually cure Jacob of his illness. In fact, the only result of this olfactory miracle is that Jacob’s family continues to consider him crazy, an accusation they have been lobbing at him since Joseph disappeared and Jacob first refused to accept his death (v. 95). Jacob’s sight returns two significant steps later. First the messenger sent by Joseph with his cloak reaches Jacob and then, as per instruction from Joseph, he throws the cloak over Jacob’s face. Only after both of these actions have been completed does Jacob regain his sight (v. 96). Unlike in Ibn Ḥazm’s poem which emphasizes the cloak’s healing smell, in the Qurʾān it is physical contact with the tunic that cures Jacob’s blindness.

While one might be inclined to think that Ibn Ḥazm here presents us with a brand new reading of the qurʾānic account of Joseph’s cloak, in which he shifts its power from the physical object itself to its aroma, in reality we find the shift from touch to smell in the qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ literature. According to Aḥmad b. Muḥammad al-Thaʿlabī (d. 427/1035), Muḥammad b. ʿAbd Allāh al-Kisāʾī (ca. fifth/eleventh c.), and Ibn Muṭarrif al-Ṭarafī (d. 453–4/1062, citing Isḥāq b. Bishr [d. 206/821]), when Joseph was stripped and thrown into the well, he called to his brothers to return some clothing to him, pleading with them not to leave him to die naked.16 The brothers callously refused, replying that if Joseph wanted something he should request it of the sun, moon, and stars of his dream.17 Now, relate these sources, when Abraham was thrown into the fiery furnace prepared for him by the evil king Nimrod, he too had been stripped naked. So God sent the angel Gabriel to him to dress him in a shirt. Significantly, this was not just any shirt, but one that was made of the silk of Paradise. Abraham’s son Isaac inherited this shirt when Abraham died, and Jacob inherited it from Isaac when Isaac died. Jacob took the shirt and placed it in an amulet which he then hung around Joseph’s neck.18 When Joseph was thrown naked into the pit, an angel—some say Gabriel, some say this was God Himself—came to him, took the shirt out of the amulet and clothed Joseph in it.19 This was the shirt he was wearing on the trip with the Ishmaelite caravan and this was what he was wearing when he entered Egypt. And this was the shirt, made from the silk of Paradise, which Joseph later sent back to Jacob with instructions to the messenger to place it over his father’s face.20

Importantly, in these accounts, this shirt is said to have had a unique and powerful scent. According to Thaʿlabī, after Joseph sent the shirt-bearing messenger on his way, the wind asked for and received permission from God to bring the scent of Joseph to Jacob before the messenger arrived. However, the wind did not blow on Joseph himself in order to release Joseph’s scent. Rather, Thaʿlabī, Ṭarafī, and Kisāʾī report, the wind shook out Joseph’s shirt and carried that scent to his father.21 Ibn ʿAbbās, as cited by Muḥammad b. Jarīr al-Ṭabarī (d. 310/923), notes that when the caravan left Egypt, the smell of Joseph’s shirt reached Jacob before the shirt itself did, even though it had to travel a distance of about eight days.22 Lest we think that the odor that reached Jacob was the smell of Joseph’s body, embedded in his cloak, Thaʿlabī and Ṭarafī explain that the shirt, created in Paradise, smelled of Paradise.23 Thaʿlabī and Ṭarafī also cite al-Daḥḥak and al-Suddī, who note that the shirt, inherited from Abraham, was woven in Paradise and had the scent of Paradise.24

In comparing the lover’s self-soothing by looking at the clothing of his absent beloved to the image of Jacob’s blindness being cured by the smell of Joseph, Ibn Ḥazm has employed a qiṣaṣ motif. On one level, this should not strike us as a puzzling move. The qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ accounts provide readers with many colorful exegetical and narrative motifs and, since Muslim poets drew from the entire corpus of Islamic literature, more than a few of these appear in Andalusian Arabic poetry. At the same time, however, we must remember that the Qurʾān provides a clear description and sequence of events for this account. Why then does the scholar Ibn Ḥazm choose the qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ version, one which seems to contradict the Qurʾān, over the Qurʾān’s authoritative version? Indeed, Ibn Ḥazm appears to consciously blur the lines between the two corpora regarding this narrative. As he writes in his introduction to this poem, the soul of a man who possesses something of his beloved feels satisfied even if the result is no more than “what God specified for us regarding Jacob’s getting his sight back when he smelled the shirt of Joseph.”25 As noted, only in the qiṣaṣ accounts does Jacob actually smell the shirt.