PDF

Download

Citations

Click and drag then release to select a passage to cite.

Annotations

How to submit annotations to Mizan Journal articles:

your work is published.

Search within

The Human Jesus

A Debate in the Ottoman Press

Image

Audio

Video

Chart or Graph

The Human Jesus

A Debate in the Ottoman Press

Introduction

Christmas 1921 saw the beginning of a heated debate between Ottoman intellectuals in a series of essays published in one of the longest-running and most renowned Ottoman newspapers, Tevhid-i Efkar (Unity of Ideas). In contrast to the literal meaning of its name, the newspaper served as the forum in which three Ottoman intellectuals (Ömer Rıza, Mehmet Ali Ayni, and Milaslı İsmail Hakkı) expressed conflicting views on the birth, death, and miracles of Jesus (Turkish İsa; Arabic ʿĪsā). This triangular disputation began with an essay by Ömer Rıza published on December 26, 1921. Mehmet Ali Ayni responded ten days later, also in Tevhid-i Efkar, and Ömer Rıza published his own response two days later. In February, Milaslı İsmail Hakkı joined the debate. The dispute between the three ended with Hakkı’s piece, but other authors took up the debate.1 While Ayni’s rebuttal of Rıza’s thoughts was relatively short, Hakkı wrote a longer essay that shared the basic assertions of Rıza’s essay.

Rıza’s and Hakkı’s interpretations of the qurʾānic Jesus narrative diverged from some of the classical qurʾānic commentaries, as well as from popular Muslim ideas about Jesus (such as his virgin birth and miracles).2 This article situates these writings in their contemporary political and intellectual milieu, contextualizing this triangular newspaper dispute on Jesus within the larger frames of Muslim debates on the translatability of the Qurʾān; the clarity or ambiguity of qurʾānic passages; encounters between Muslim and non-Muslim intellectuals regarding missionary writings and refutations; and transregional Islamic movements advocating new approaches to tradition within the broader frame of Muslim engagements with the secular modern.

Contemporary intellectual currents such as rationalist and scientific interpretations of miracles that were claimed to be more plausible and harmonious with human understanding substantially shaped the essays on Jesus in Tevhid-i Efkar. Rıza and Hakkı argued that Jesus’s conception was natural rather than miraculous and that Mary conceived Jesus through sexual intercourse—even if that intercourse was with an angel in the form of a man, or a prophet, or a complete and perfect man. Their essays touched on other elements of the Jesus narrative—his crucifixion, death and resurrection, and miracles—but the crux of the arguments was his birth. It was the celebration of the birth of Jesus that incited the dispute, so it is not hard to grasp the focus on his conception. Yet Jesus’s birth was also debated as part of larger deliberations over the role of human reason in understanding the Qurʾān (prophetic narratives as well as other passages), the clarity of qurʾānic passages concerning historical details about prophets’ lives, and the presumed ideal nature of the relationship between the human believer and the timeless message of the revelation. In this way, the debate on Jesus’s birth also served as the basis for related discussions about his miracles, ranging from his resurrection to the healing of the sick.

This debate took place in a newspaper; that is, it was addressed to a general reading public. The authors were Muslim intellectuals—not Islamic jurists, scholars, or clergy—who engaged questions pertaining to Islam and other contemporary matters and expressed their opinions in the popular press. They did not have vigorous official training in Islamic sciences, but rather had graduated from modern schools. Ömer Rıza (1893–1952) had had some training at Al-Azhar University in Egypt, but even he was primarily a journalist.3 Mehmet Ali Ayni (1869–1945) was a bureaucrat and a graduate of Ottoman civil-servant training and taught philosophy and history of religion at Istanbul University.4 Milaslı İsmail Hakkı (1880–1937) was a medical doctor by profession but engaged religious and social topics beyond his profession.5 These intellectuals’ writings on Islam extended beyond the issue of the Jesus narrative in the Qurʾān.

Their essays on Mary’s conception of Jesus only occasionally referred to earlier and contemporary exegeses of these qurʾānic verses. Rather, they were based on their own interpretations of a set of qurʾānic passages they saw as relevant to the Jesus story. Their arguments had consistencies and sound points as well as inconsistencies and weaknesses. Yet these individual readings and understandings, especially in the case of Rıza, were also intended to be conveyed to others, as evident in his choice to publish these articles in a newspaper and later in his Turkish translation of the Qurʾān.6 Intellectuals such as Ayni and ʿulamāʾ such as İskilipli Mehmet Atıf, as well as Ottoman religious-bureaucratic authorities, were all prompt to challenge Rıza’s and Hakkı’s arguments, attempting to discredit them and to save the Muslim public from what they saw as their negative influence.7 All parties considered the press a crucial medium to reach out to the public, influence people, and propagate ideas and opinions.

In this regard, this article, similar to several other studies on modern Islam, emphasizes the critical role played by the press in serving as a medium to express, debate, and proliferate ideas within and across different regions of the Islamic world. However, it also brings to our attention the control and censorship mechanisms the modern state imposed on religious publications. The criticism and censorship mechanisms to which these articles on Jesus were subjected by the Ottoman Islamic print administrative body Tetkik-i Mesahif ve Müellefat-ı Şerʿiyye Meclisi (Council on the Inspection of Printed Qurʾāns and Islamic Religious Publications) are investigated closely. This Islamic print control council served under the Meşihat, which was the bureaucratic office of the Sheikh al-Islam after the nineteenth-century Ottoman administrative reorganization. 8

The contemporary political and intellectual milieu

Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Muslim intellectuals and ʿulamāʾ across different regions from North Africa, Central Asia, and South Asia to the Arab world and the Ottoman domains participated in intellectual engagements categorized in scholarly literature as ‘reformist’ or ‘modernist,’ in contrast to ‘conservative’ or ‘traditionalist’ Islam.9 Yet we must pay attention to the fact that a wide range of positions were possible in between these two extremes, as well as that those on both sides engaged similar subjects, problems, and issues. Even though the labels ‘reformist’ and ‘traditionalist’ are applied based on the answers intellectuals provided to questions, these identifications must be deployed cautiously, keeping their limitations in mind.

The power of modernity and European colonialism forced each Muslim intellectual and scholar to question the existing socioeconomic, legal, institutional, and political establishment and to produce alternative formulations. Muslim discourses on modernity were accompanied by structural transformations of Muslim polities and societies. The development of industrialization and the capitalist mode of production; the predominance of legal-rational bureaucratic authority; the rise of new educational models and the spread of literacy and cultural capital to wider segments of society; and the prevalence of post-Enlightenment conceptions of reason, individuality, and scientific thinking were some of the most basic patterns of modernity, emerging in non-Muslim as well as Muslim domains. Muslim intellectuals and ʿulamāʾ took part in these transformations both intellectually as well as practically to “self-strengthen” their states and societies.10 They responded and reacted to the secular modern as they also constituted and molded it.

In line with the increased differentiation and demarcation of domains under modernity, the public roles of religion were redefined. Categorically defining religion, revising conceptions of different elements of religious thinking and approach, and reassessing the interaction between religion and other domains comprised substantive dimensions of modernity and Muslim intellectuals’ engagements with it. Muslim articulations of the characteristics of modern religion, in particular Islam, involved engaging in debates with both non-Muslim and Muslim, secular and Islamic ideas and interpretations.

The Ottoman periodical dispute on Jesus between the three intellectuals in Istanbul incorporates and reflects these briefly outlined features of the contemporary historical, political, and intellectual milieu. In these essays, as well as in their other publications, these three Ottoman intellectuals addressed Christian missionary or colonizing Orientalist writings, as well as other Muslims’ perspectives.11

It has been argued that publications by Christian missionaries praising Jesus over Muḥammad, especially in India, encouraged contemporary Muslim intellectuals to cast doubt on Jesus’s miracles and virgin birth.12 The desire to intellectually refute missionary writings and Christian perspectives might have also colored Ottoman intellectuals’ writings on Jesus. Both Hakkı and Rıza emphasized that the qurʾānic Jesus narrative is primarily structured to refute Christian doctrinal views, and Rıza stated explicitly in his complete Qurʾān translation that the primary purpose of the Qurʾān is not to supply details about the individual life of Jesus. All details about his birth, including the references to Mary’s birth pains, are given, according to Rıza, to refute Christian beliefs, including the idea of Jesus’s divinity, and to underline his humanity.13

While it is important to take into account the fact that these Muslim intellectuals’ engagement with the Jesus narrative was part of a broader effort to distinguish Islamic conceptions of Jesus from those of Christianity and to defend the former in the face of Christian missionary activities, it is equally significant to evaluate their writings in light of their investments in contemporary Muslim, Christian, and secular debates on demarcating the spheres of religion and science, (re)defining the role of reason in religious interpretation, and criticizing irrational and derivative elements of traditional religious thinking. Accordingly, these three Muslim intellectuals’ approaches to the qurʾānic Jesus narrative were not only reacting to Christian missionary writings but also actively engaging in contemporary Muslim and non-Muslim formulations of modern approaches to religion.

This is particularly true for Ömer Rıza, who not only published numerous books and translations, but also actively took the role of a public intellectual aiming to spread what he considered “true Islam.” The latter, in his view, necessitated both refuting criticisms raised against Islam as an irrational religion and changing Muslim interpretations that adopted a “miraculous” rather than a “natural” understanding of the qurʾānic text.

Despite arriving at different conclusions, these three Ottoman intellectuals each chose to write and proliferate their views in a popular publication that could reach a wide audience. Each revisited the qurʾānic Jesus narrative through his own reading and interpretation of the qurʾānic sūrahs. More and more, sacred texts were presumed to be accessible by individual believers without the intermediation of established interpretations and religious scholars. The texts were perceived to be “naturally” open to the individual believer’s understanding. However, it was granted that the reader/believer could benefit from other Muslim or non-Muslim explanations at their choice.

It was the understanding of miracles that constituted one major element distinguishing these Ottoman intellectuals’ ideas from conventional explanations. Here Rıza and Hakkı criticized and denied several literal understandings of the Jesus narrative in the Qurʾān in accordance with the prevailing criticism of miracles current at the time. Their readings followed a strong tendency in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to seek a rationalist explanation for miracles.14 Although such approaches existed in the premodern era, providing a rationalist and naturalistic understanding of miracles is not only typical of modern conceptions of religion, but it also appealed to wider circles, as seen in this case by the fact that this three-way dispute took place in a newspaper.

There are striking similarities and continuities concerning the denial of the virgin birth and the figurative understanding of miracles between Rıza and other prominent names affiliated with modernist or reformist Islamic thought, specifically Muhammad Abduh, Sayyid Ahmad Khan, and Mawlana Muhammad Ali. Indeed, both Rıza and those rejecting his interpretation of the qurʾānic Jesus narrative explicitly acknowledged his intellectual debt to Muhammad Ali. Through his intellectual and publication circles, Rıza was already familiar with the works of an earlier generation of Muslim intellectuals that advocated some ideas similar to his. His father-in-law, Mehmet Akif, was a main contributor to the prominent Ottoman Islamic journal Sırat-ı Müstakim, which was publishing translations of Abduh and other influential Muslim intellectuals’ works. Muhammad Ali was a contemporary of Rıza, and Rıza was not only influenced by his ideas but also wanted to spread them in Turkey, as is evident from his translation of some books by Muhammad Ali, who was formerly affiliated with the Ahmadiyyah movement in India.15

The Ahmadiyyah movement emerged in 1889 under the leadership of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad in Punjab.16 The name of the movement is generally considered to derive from the name of the founder, Ghulam Ahmad, yet in Turkish it is also referred to as Kadiyanilik due to the town, Qadian (Kadiyan in Turkish), in which it first developed. Following the death of Ghulam Ahmad in 1908, and that of his successor Nur al-Din in 1914, a split occurred within the movement between the Qadiani and Lahori groups due to doctrinal as well as political differences, including the question of whether Ghulam Ahmad was believed to have been a prophet or not.

The Lahori group, led by Mawlana Muhammad Ali (1874–1951), believed Ghulam Ahmad to be only a messiah, or renewer of religion, not a prophet. Moreover, it rejected the presentation of the Ahmadiyyah as a separate sect, even though it still sought to spread the teachings of Ghulam Ahmad to proliferate “true Islam.” Muhammad Ali received a modern education and completed a M.A. in law and English literature, and translated Ghulam Ahmad’s writings into English.17 He wrote numerous books on the Qurʾān, Muḥammad and Jesus, and Islamic theology, as well as about the Ahmadiyyah movement itself.18 Muhammad Ali also showed support for the Ottoman caliphate, penning two pamphlets for this purpose.19

Yet Muhammad Ali was approached with caution by many Sunni Muslims for following Ghulam Ahmad, taking him as the messiah, and adopting elements of modernist thinking, particularly about science. Indeed, Rıza’s opponents in Turkey pointed out the parallels between his approach and that of the Ahmadiyyah sect. Even though some of them targeted Rıza’s personal habits too, such as his drinking alcohol, and implied that such impiety would also lead him to misunderstand the Qurʾān, their main criticism focused on Rıza’s inspiration by the Ahmadiyyah sect, and in particular, Muhammad Ali.20

Despite these criticisms, Ömer Rıza translated Muhammad Ali’s Qurʾān translation into Turkish under the title Kur’an’dan İktibaslar (Selections from the Holy Quran) in 1934, the same year as his own translation of the Qurʾān. The book itself is 125 thematic selections from the Qurʾān. Rıza also translated a book by Muhammad Ali that was penned as a refutation of Orientalist claims about the Prophet Muḥammad. Addressing these criticisms, Rıza praised Muhammad Ali. He pointed out that while the Qurʾān had been translated into English by Western scholars, Muhammad Ali was the first great Muslim scholar to produce an English translation of the Qurʾān,21 that he was no longer affiliated with the Ahmadiyyah movement and was a fully committed Sunni Muslim, and that his works did not contain any elements contradicting Sunni doctrine.22 But Rıza also denied being influenced by either Muhammad Ali or the Ahmadiyyah movement.23 However, in his 1934 Qurʾān translation, he stated that he had been influenced by both classical and contemporary exegeses, including those of Muhammad Abduh, Sayyid Ahmad Khan, and Muhammad Ali.24 In the 1947 edition, he directly cited Muhammad Ali’s renditions of certain qurʾānic passages.

The conception of the Qurʾān in the Jesus debate, 1: the clarity or ambiguity of qurʾānic passages

On December 26, 1921, taking as his starting point the Christian celebration of Jesus’s birth, Rıza questioned whether Jesus had indeed been born on the twenty-fifth of December.25 However, his main concern was not the precise historical date but rather the question of whether Jesus’s conception and birth involved any miraculous or extraordinary features, distinct from the experience of other human beings. Rıza asserted, “Hazret-i İsa [the revered Jesus] was born like any human being, lived like any other human being, and died like any human being.”26

While Rıza rejected the idea of a birth and death that defied the laws of nature, Ayni posed a rhetorical question. He asked why, if Rıza’s claim was accurate and Jesus’ birth was similar to that of any other human being, and in that regard Jesus was just an ordinary human being, individuals had been reflecting on and debating his position as God and/or the son of God for almost two millennia.27 Although Ayni was not suggesting that Rıza should adopt a Christian perspective on the issue, he used centuries of Christian articulations to hint at the unique nature of Jesus’s conception and its complex interpretations.

In the same way, Ayni challenged Rıza by asking on what basis he formulated his theory, because in his view, the Qurʾān definitely affirms that Jesus was conceived by Mary without a father, that is, without sexual intercourse with a male human being. In his words, “We Muslims believe that Jesus was born without a father based on the explicit way the Qurʾān reports about it.”28 Thus, in Ayni’s view, Muslims believe based on the qurʾānic text that Jesus was born without any sexual intercourse between Mary and another being, human or not, and in this way, his birth was definitely different from that of other human beings. He did not ascribe any divinity to Jesus but still set his conception apart from the experience of the rest of humanity, and according to him, the Qurʾān, the prime Islamic text, narrated and confirmed this extraordinary feature.

Rıza focused on precisely this point in his response, and fervently refuted Ayni’s stance on the clarity of the qurʾānic passages. He did not reject Ayni’s statement that the Qurʾān must serve as the most basic tool to ground and understand prophetic narratives. However, he proposed just the opposite of Ayni’s argument, arguing that “there is not any qurʾānic explicitness (sarahat-i Kuraniye)” on the issue of Jesus’s birth.29 He denied that the qurʾānic narrative was so explicit that his interpretation of the relevant verses contradicted it.

In accordance with one of the most prevalent themes of modern Islam, Rıza accused Ayni of “blind imitation” (taklid)—that is, of understanding qurʾānic verses only in terms of established interpretations. Rıza associated the qurʾānic text’s lack of clarity, precision, and certainty with its openness to multiple interpretations over time, and thus criticized his opponent’s following of conventional understandings. In Rıza’s words, Ayni “read [these verses] with a perspective of imitation rather than examination and interpretation and hence understood [them] as such” (tedkik ve tevilden ziyade nazar-ı taklid ile okumuşlar ve öyle anlamışlardır).30 In contrast, Rıza advocated the close study of the qurʾānic verses and welcomed new, contemporary, modern interpretations.

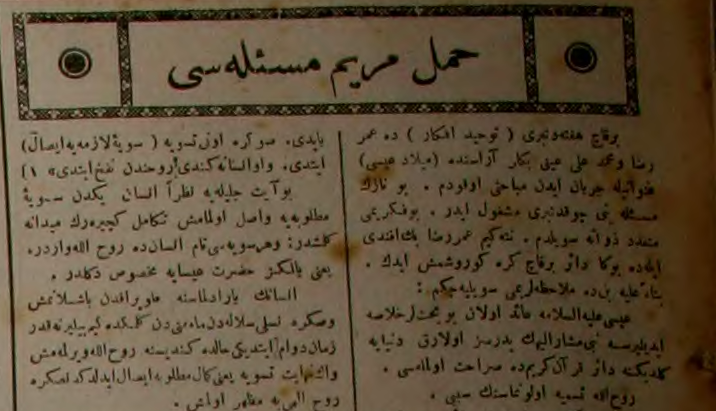

M. İsmail Hakkı, the third person to engage in this newspaper exchange (see Gallery Image A), stated that this “delicate issue” had long occupied his mind, and argued that qurʾānic verses could be divided into two categories: those that clearly set out certain aspects of the Jesus narrative, and those that were intentionally left open to different understandings.31 It was not a random choice. Issues that directly engaged fundamentals of Islamic faith were precisely clarified in the Qurʾān; for instance, on the question of whether Jesus had divine attributes, Hakkı underlined that the Qurʾān explicitly denied that Jesus was the son of God, as this would contradict a pivotal element of the Islamic doctrine of the unity of God (tawhid).32 However, treatments of inessential components of faith were left imprecise because matters such as Mary’s pregnancy or Jesus’s father did not impact the prime question of Jesus’s divinity. Hakkı asserted that unsubstantial components of the Jesus narrative are not detailed in the Qurʾān so that the revelation remains open to the understanding of each age.33

In Hakkı’s perspective, this choice of clarity and precision versus ambiguity and susceptibility to multiple interpretations was not peculiar to the Jesus narratives in the Qurʾān. Rather, except for matters in which one must have absolute faith—the five pillars of Islam, belief in God and His prophets, the revealed books, angels, and the Day of Judgment—the Qurʾān was open to debate and discussion, and an individual interpreter with a divergent opinion might be mistaken, but that would not jeopardize their faith.34 Differentiating between the essential elements of the religion and tangential matters, Hakkı allocated the deployment of free, innovative reasoning to the latter and allowed it only for a person who already has faith in the essentials. The individual believer and their interpretation was held higher than the binding consensus (Turkish icma; Arabic ijmāʿ) and the preceding interpretations of different religious interpreters (Turkish müctehidler; Arabic mudjtahids). In his words, “the way of understanding and viewpoint of an individual who is completely devoted to the true religion can be impeded neither by müctehidler nor by the icma” (böyle asıl dine merbutiyeti tam olan bir kimsenin suret-i fehm ve telakkiyesine ne müctehidler ne de icma mani olamaz).35 In Hakkı’s view, the authoritative consensus was binding only regarding the fundamental elements of the faith.

Accordingly, similar to Rıza and many other modern Muslim intellectuals, Hakkı criticized imitation and limited the binding nature of the views of prominent individual religious scholars and their consensus to the essentials of religion. Individual believers could intervene to draw out the potential meanings embedded in divine revelation, even if their interpretations had not been yet voiced or had previously been refuted by religious scholars. In Hakkı’s formulation, revelation embodied a universal truth that was valid for each age and society; however, it was the individual believer’s responsibility to instantiate that truth, to decipher its layers of meaning for the present moment. Hakkı argued that such an approach did not contradict established religion and revelation because it was the nature of divine texts—particularly the Qurʾān—to be relevant to every era. “One of the greatest miracles of the Qur’an,” Hakkı contended, is that “it encompasses truths that can be interpreted according to the understanding and conscience of each age” (Kuran-ı Kerim’in en büyük mucizelerinden birisi de her asrın fehm ve vicdanına göre kâbil-i tefsir hakayiki muhtevi olmasıdır).36

Hakkı’s perspective carries a third element of the modern religious inclination, in line with the criticism of imitation and the limited legitimacy assigned to the existing binding consensus of religious scholars. This is the call to remove intermediaries between individual believers and the sacred text. Muslims are encouraged to have direct contact with the Qurʾān, and the latter is considered to encompass truth that can be verified, affirmed, and attested according to every contemporary epoch. It is the unique feature of the Qurʾān to include truth the layers of which can be unpacked differently across time and society, and it is the task of individual believers to decipher the meanings in accordance with the period in which they live.

The conception of the Qurʾān in the Jesus debate, 2: the Qurʾān as a printed and translated book

The issue of the multiplicity of meanings in qurʾānic passages is also related to another prominent question of the time, namely the translatability of the Qurʾān into non-Arabic languages. Hakkı engaged in this question, and while serving as a health inspector in Beirut, sought out the opinions of Christian Arabs regarding Arabic and the translatability of the Qurʾān. Based on their articulations of the difficulty of adequately translating the Qurʾān into another language, he contended that rather than individual scholars, a committee should translate the Qurʾān, adding that wherever multiple meanings are embedded in the original verse, the translation should mention all these meanings. 37

His idea that a committee should translate the Qurʾān so that the translation work can provide a richer, multi-layered account is also evident in his openness to different interpretations of the qurʾānic Jesus verses. Hakkı offered in detail his interpretation of the qurʾānic Jesus passages, but he also emphasized that these were the meanings that came to his own mind, and any Muslim could refute them as long as they had counter-proofs.38 In this respect, Hakkı’s approach differed from that of Rıza, who not only undertook a Qurʾān translation on his own but also presented his understandings in more absolute terms than Hakkı. In their explanations of the qurʾānic Jesus narrative, Hakkı emphasized that the qurʾānic passages were susceptible to varying interpretations more than Rıza. In Hakkı’s view, the qurʾānic text clarified certain elements of Jesus’s prophecy, but also weaved the narrative through “indications and hints” (delalet ve işarat), leaving the latter open to multiple interpretations in any particular moment in history.39

It was not only Hakkı and Rıza that discussed the qurʾānic Jesus narrative in juxtaposition with the issue of Qurʾān translation, rendering the Qurʾān into vernacular languages other than Arabic. Indeed, as Brett Wilson underlines in Translating the Qur’an in an Age of Nationalism, the Muslim debates on the translatability of the Qurʾān predate the modern period, but print technology and culture, as well as accompanying changes in religio-political authority and institutions, renewed the significance of Qurʾān translation, making it an essential component of many other influential modern Muslim debates.40

Qurʾānic codices were not only officially printed in large numbers in Ottoman lands since the late nineteenth century; the meanings of qurʾānic verses were also being discussed at length in Turkish, in a vernacular language accessible and comprehensible to ordinary readers in periodical publications. As Wilson points out, since the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, “Muslims across the globe have embraced printed editions and vernacular renderings of the Qurʾān, transforming the scribal text into a modern book which can be read in virtually any language.”41 As such, while numerous discussions of the translatability and meanings of qurʾānic passages were ongoing, numerous official and unofficial, state-sponsored as well as individual Qurʾān translations were being put forward.42 The translators did not come only from the ʿulamāʾ class but included Muslim intellectuals, too, and Rıza was one of them. He had some traditional ʿulamāʾ training in Cairo but throughout his life pursued a career as a journalist and a public intellectual, yet undertook a complete Turkish Qurʾān translation. Hakkı, similar to Rıza, was not a religious scholar by profession, but similar to many other intellectuals, columnists, and ordinary readers and authors writing in periodicals about religious matters, he participated in public debates on religion, including how to understand and translate the qurʾānic text—yet, unlike Rıza, he did so while emphasizing the contemporary and individual connections between believers and the Qurʾān. Hakkı also underscored the necessity of collective efforts, such as creating Qurʾān translation committees.

Although it is crucial to take into account the modern context in which the Qurʾān emerged as a book produced in multiple editions and languages (in which these translations also traveled beyond national boundaries and contributed to shared intellectual trends, such as the connections between Rıza and the Ahmadiyyah), it is equally vital not to underestimate the power and regulatory capacities of the modern state. As underscored in the final section of this article, the modern state, in this case the Ottoman imperial state apparatus, was a crucial actor in overseeing, approving, controlling, rejecting, restricting, or censoring Islamic writings, including qurʾānic passages, in books, booklets, and periodicals.43 It might not be the case across different Muslim polities, but in both the late Ottoman Empire and the early Turkish Republic, modern state structures were key agents in overseeing the entire process of Islamic book printing and dissemination, including printed qurʾānic codices and their translations. In this regard, both the Qurʾān as a printed book as well as the Qurʾān as a translated and interpreted text were subject to state approval. The state could face resistance, or fail in its control and censorship efforts; but its role in controlling the spectrum of different Muslim intellectual engagements with the Qurʾān cannot be dismissed.

The conception of the Qurʾān in the Jesus debate, 3: the reasonable or rationalized Qurʾān

As an intellectual matter, at the heart of Ayni, Hakkı, and Rıza’s debate lay not only the questions of the Qurʾān’s translatability and the clarity versus ambiguity of the qurʾānic passages, but also the related issue of the role of human reason in comprehending and interpreting God’s message. If qurʾānic passages conflict, or appear to conflict, with human reason, does this conflict imply an internal contradiction in the divine revelation? In these three intellectuals’ disputation, these questions were not discussed in an abstract manner, but were grounded in the specific, concrete case of the birth of Jesus. Ayni affirmed that it is not easy for the human mind to grasp the unnatural or miraculous nature of the birth of Jesus. However, he also emphasized that human reason or intellect (Turkish akıl; Arabic ʿaql) cannot be taken as the sole means of comprehension or of judging the truth and validity of phenomena, and that even though it is hard to grasp or even contrary to human reason, Mary’s virgin conception of Jesus needs to be understood as it is (Ayni believed) explicitly narrated in the Qurʾān.44

Rıza shared Ayni’s belief that rationality is not the exclusive criterion of truth; however, he strongly rejected unnecessary obfuscation of rational matters. He suggested that there was a hierarchy of methods through which one could come to know the truth, and that if a matter could be explained rationally, it would be unwise to seek out irrational explanations. As he put it, is it not “an inappropriate act to attribute to the things that can be comprehended by reason an unreasonable [irrational] character and to modify them into an incomprehensible form?”45

Applying this principle for Rıza entailed choosing a more rationalist explanation for Jesus’s birth, death, and miracles. Rıza denied the extraordinary nature of the birth and death of Jesus as a way to render the event comprehensible to the human intellect. His advocacy for rendering hard-to-grasp elements understandable through human reason required affiliating the reasonable/rational with the natural, the common, the ordinary, and the non-miraculous—an approach best revealed in his emphasis on the similarity of Jesus’s experience (particularly his birth) to that of any other human being, which contested Mary’s virgin conception of him.

In what follows, we will examine Rıza’s and Hakkı’s rationalized approaches to the elements of the Jesus narrative in the Qurʾān at length. We will thus illustrate in detail these two intellectuals’ methodological stances regarding the clarity, precision, and translatability of the qurʾānic text, as well as their substantive arguments with respect to these qurʾānic Jesus passages.

Rıza on the qurʾānic Jesus

In his essay in Tevhid-i Efkar, Rıza based his ideas on Mary’s conception of Jesus primarily on the nineteenth sūrah or chapter of the Qurʾān, Mary (Maryam in Arabic). He focused particularly on verses 16 to 40 and did not cross-reference these verses with other qurʾānic passages. Although these verses contain the most comprehensive account of Jesus and Mary in the Qurʾān,46 and as such Rıza’s focus on them makes sense, it is also true that he excluded other relevant verses. Similarly, Rıza’s examination of Jesus’s death and miracles focused only on selected verses instead of pursuing an all-inclusive, comparative reading of all the relevant qurʾānic verses.

For example, Rıza did not address Sūrah 3, particularly verses 37 to 45, which contains the longest narrative on Mary and Jesus in the Qurʾān outside Q 19; Q 3:47 (in which Mary expresses her wonder at how she could conceive a child when no one had touched her) is usually taken as one of the strongest pieces of qurʾānic evidence for the virgin, or at least exceptional, conception of Jesus. Likewise, Rıza did not pursue a comparative analysis with Q Taḥrīm 66:12 and Q Anbiyāʾ 21:91, which, similar to Q Maryam19:17, describe Mary’s chastity in juxtaposition with God’s spirit. In Q 19:17 the divine voice in the Qurʾān speaks of sending the spirit to Mary, whereas Q 66:12 and Q 21:91 state that God breathed his spirit into her.47

Rıza did not explain how his understanding of these verses contributed to or challenged his explanation of Jesus’s natural birth. He rather focused on Q 19:17 and on the parallel drawn between the spirit that was sent and its appearance to Mary in the form of a man, thereby identifying the spirit with a human being in order to support his argument that Jesus “was not born without a father” but rather was conceived through this spirit/man. Rıza did not discuss at length the scientific or practical explanation of how a human being comes into existence, and did not use the explicit term “sexual intercourse,” but from the overall content of his articles—especially his emphasis on the “naturalness” of Mary’s conception, the existence of a father for Jesus, and the similarity of Jesus’s experience to that of any other human being—he clearly implied Jesus’s origin through sexual intercourse.

According to Rıza, Jesus’s birth and death were neither unnatural (significantly different from other human beings’ natural experiences of birth and death) nor unreasonable (incomprehensible by human mind or implausible to human reason). To support this argument, he not only focused on certain qurʾānic passages while ignoring others, but also—even within this selected cluster of verses—chose to attend very closely to certain vocabulary. For instance, for him one of the strongest pieces of evidence for Jesus’s natural birth was the word ghulām in Q 19:19. Since ghulām means young man or boy, Rıza argued, and is used to refer to Jesus, it indicates he was born in a natural way like any other boy.48 Rıza, however, did not explicate the fact that although ghulām means a young boy, and the verse indicates that Jesus was bestowed upon Mary as a son, it does not shed light on whether his conception by Mary was natural or occurred in another manner.

Regarding not only the birth but also the death of Jesus, Rıza focused on certain qurʾānic passages and vocabulary. He argued for the natural death of Jesus, based on Q 3:55, and particularly the word mutawaffika, a derivation of tawaffā from the root w-f-y, meaning “taking back” or “causing to die.”49 Rıza asserted that mutawaffika means “to be dead,” as it is defined in various qurʾānic exegeses, prophetic sayings (ḥadīth), and prominent Arabic dictionaries, and so he concludes that Jesus had a “natural leaving of life.”50 However, he did not discuss the ambiguous meaning embedded in this word, whether it means killing someone or taking someone back and raising him, as the word is followed by the word warafiʿuka (whose root is r-f-ʿ, that is, “to raise”). He did not refer to other relevant qurʾānic verses such as Q Nisāʾ 4:157–158 that seem (and are interpreted in several commentaries) to explicitly refute Jesus’s death on the cross and rather affirm his ascension to the heavens.51

Rıza did not account for the fact that some qurʾānic passages seem to affirm and others seem to deny the death of Jesus, nor did he point out the lack of certainty in the Qurʾān’s account and the wide room it leaves for speculation.52 In other words, he contradicted his own methodological stance, in which, in response to Ayni, he emphasized that the qurʾānic passages lacked certainty and explicitness. Yet instead of acknowledging the room for different (even contradictory) interpretations, he proposed his reading as one affirmative understanding of the qurʾānic narrative.

In this regard, he followed more closely another of his methodological principles, which was that if a rational explanation can be easily proposed it is unwise to search for irrational explanations, and that Jesus’s death, just like his birth, could be explained rationally. When one can easily presume Jesus’s natural death, Rıza argued, it is unnecessary to look for other kinds of explanation. In response to Ayni’s statement that he found it hard to grasp how, at the crucifixion, Jesus was raised above and a substitute replaced him, Rıza asked why Ayni did not accept Rıza’s proposal that Jesus died naturally, which is supported by Q 3:55 of the Qurʾān.53 Thus, he proposed that Jesus died just like any other human being who comes into the world and then leaves it, and is said to be buried in Kashmir—an idea also proposed by followers of the Ahmadiyyah movement, an Islamic sect in India whose influence on Rıza I discussed previously.54

Rıza found evidence for his ideas on Jesus’s birth and death not only in qurʾānic phraseology but also in certain extended descriptions in the qurʾānic verses. The Qurʾān’s portrayal of Mary’s pain in childbirth, especially in Q 19:23–26, provided Rıza one of the strongest pieces of evidence for his argument for a normal birth process. Further, he reasoned that the word ghulām for Jesus indicated a naturally born child. Mary’s experience, he argued, was similar to the “ordinary conditions of any other woman going through pregnancy and birth.”55 Her birth pains show that “a very ordinary (pek tabii) child was arriving in the world,” that this incident carried no “extraordinariness” (fevkaladelik).56 Thus, he argued, if Jesus was a ghulām, a young boy, and if his birth was like any other, then his conception must have also occurred in the normal human manner.

Rıza did not address at length the question why, if the conception was normal and ordinary, Mary expressed fear of the man-shaped spirit sent to her (Q 19:18), and even asked explicitly how she could have a son when no man had touched her and she had not been unchaste (Q 19:20)? He argued that her questioning was just a reflection of the pain that she experienced in the last stages of pregnancy and imminent delivery. Mary’s question was meaningless for Rıza except to underline the hardship of pregnancy.57

In his newspaper essays, Rıza focused primarily on Jesus’s birth, based his arguments primarily on Sūrah 19 of the Qurʾān, and focused closely on selected words and passages, ignoring passages that contradicted or weakened his argument and embodied alternative understandings.58 At the same time, he added interpretive elements that had no explicit basis in the Qurʾān, connecting one idea with another without textual proof. For example, interpreting Q 19:17, he argued that the spirit sent by God to Mary must have appeared to her “in a world of dreams rather than in the physical world.”59 This verse and subsequent ones do not refer to dreams. However, Rıza, possibly drawing on ideas from other exegetical sources, asserted that human beings can see angels in dreams as young men, and since angels can take on human likeness in dreams, this encounter between Mary and the spirit must have occurred in a dream.60

In this regard, strikingly, Rıza did not pay attention to the word “spirit” (rūḥ) in the same verse, although it is one of the most evocative words in the Qurʾān.61 It seems he added dreams as an element to render the encounter between Mary and the spirit more plausible to the human mind, implying that such a hard-to-grasp encounter, even if the spirit appeared in the form of a human being, did not actually occur in the physical world but in the intangible world—and different state of consciousness—of dreams. Rıza argued that Q 19:17–20 can be interpreted as meaning that the spirit was an angel,62 or an angel in the form of a human being, seen in a dream, or just a human being63—but no matter which, the crucial point is the natural conception and birth of Jesus.

Hakkı on the qurʾānic Jesus

Unlike Rıza, M. İsmail Hakkı put the term “spirit” at the center of his understanding of the qurʾānic Jesus narrative and built a significant amount of his argument about Jesus’s conception on the usage of this term. He noted that he had studied qurʾānic commentaries and other works to grasp the meaning of the term, but that ultimately, it was the qurʾānic verses themselves that helped him understand its meaning, particularly in the narration of Jesus’s birth.64 Hakkı focused extensively on the words “spirit” and “well-proportioned man” (basharan sawiyyan) used in Q 19:17 and contextualized them in the framework of their other occurrences in the Qurʾān.

His ultimate conclusion about the birth of Jesus was no different from Rıza’s; that is, he also proposed that Jesus was conceived naturally, like other human beings. However, unlike Rıza, he arrived at this conclusion not through the evidence in Sūrah 19, but by comparing Q 19:17 with other qurʾānic passages about the creation of humankind. In other words, he did not adopt an all-inclusive and comparative method that contrasted different qurʾānic passages on Jesus either. Instead, he rather chose the set of qurʾānic verses about human creation to compare and contrast with those that refer to Jesus. In this respect, Hakkı paid close attention to Q Sajdah 32:7–9, which describes the stages of the creation of humankind from clay and from a lowly fluid, ending with the breathing of spirit into the human being.65 Comparing Q 19:17 and Q 32:7–9, Hakkı asserted not only that similar words (particularly “spirit”) are used in these different passages but also that they recount a similar process of human creation. Hakkı concluded, therefore, that the spirit mentioned in Q 19:17 is the spirit of God, as it is in Q 32:9, and that in this regard, it is just another instance of God breathing his spirit into humankind.66 Yet, God does not breathe His spirit into every human being, but rather into those who train themselves religiously and are morally suitable to receive his spirit. In other words, what distinguishes Jesus from other human beings is that whereas only some normal adults reach a level suitable to receive the spirit of God, Jesus arrived at such a condition already as a child.

Hakkı also paid close attention to the notion of rabbanilik (the state of being worshippers of God, or recognizing God’s lordship) mentioned in Q 3:79.67 He proposed that rabbanilik is a character trait that God bestows upon those who have lived a religious and spiritual or moral life (diyanet ve maneviyat hayatına nail olmuş kimseler).68 He linked this state of worshipping nothing but God with that of receiving the spirit of God as described above, and also connected it to the stages of human creation, as well as to the specific category of human being called the prophet. This high state of being a pure worshipper of God was achieved, according to Hakkı, as a consequence of completing a certain religious and moral development and acquiring the knowledge of God (marifetullah).69 Hakkı did not detail his understanding of prophethood but connected the Qurʾān’s narration of the birth of Jesus, the breathing of God’s spirit into human beings, and the general state of prophethood (Q 19:17–30, Q 32:7–9, and Q 3:79).

For Hakkı, Mary conceived Jesus through this spirit, which is, in his understanding, the one described in Q 3:79—that is, the one that went through the process of rabbanilik. Thus, even though Hakkı asserted that Jesus had a father, he did not arrive at this conclusion through the same reasoning and evidence that Rıza applied. Rather, according to Hakkı, Mary conceived Jesus through a man who had reached a sufficiently high level of knowledge of God to receive God’s spirit, possibly a prophet, but certainly a perfect human being (zat-ı kamil); Jesus later also achieved such knowledge and received the spirit of God. In this way, Hakkı proposed, the chain of prophets remained connected, forming links between Adam, Jesus, and Muḥammad.70

Hakkı argued that God can create things in any way he wants, and it is true that numerous verses attest his creation of man from nothing by simply ordering, “‘Be,’ and it is,” as in Q 3:47 in which God responds to Mary’s concern about how she could have a child when no one had touched her. In this regard, although one can presume that God created Jesus without a father, since there is no explicit qurʾānic statement about the virginity of Mary, he argued, it is more consistent to read the qurʾānic narrative of Jesus’s conception with that of other qurʾānic verses, particularly those on spirit that he himself cited.71 As for these other verses that affirm that God can create things from literally nothing, implying that Mary could conceive a child without sexual intercourse, Hakkı asserted that it is better to interpret them as pointing to the human (as opposed to divine) features of Jesus. That is, similar to Rıza, Hakkı proposed that such qurʾānic passages refuted Christian conceptions of Jesus’s divinity.

Literal versus figurative understandings of Jesus’s miracles

As much evidence as Rıza and Hakkı could find in the Qurʾān to refute the notion of the miraculous birth of Jesus, doing the same for his miracles remained a challenge. They solved the problem by interpreting the qurʾānic passages in ways that ascribe to them meanings beyond the obvious literal ones. Both Rıza and Hakkı advocated understanding references to Jesus’s miracles as figurative rather than literal and deciphering the meanings embedded beneath the surface.

Ayni asked how, if Jesus was born just like any other human being, he could have performed miracles such as healing the sick and making the blind see.72 Rıza countered that other prophets were credited with miracles without being ascribed a miraculous birth.73 But at the same time, he advocated against taking the miracles literally. He believed that his figurative interpretation harmonized more with the natural order of things and allowed the human mind to more readily comprehend the events of the narrative.

Thus, for him, when Jesus healed the sick, it was not corporeal sickness they were relieved of but rather moral or spiritual (manevi) sickness. What Rıza seems to imply is that it is irrational to believe that Jesus, as a man (even though a prophet), could have a supernatural capacity to heal the physical body, which operates according to the laws of nature. However, he might have the capacity for spiritual or moral healing, as that realm is beyond the rules of nature. In the same way, he asserted that Jesus would not have been able to bring the dead back to life, and that what qurʾānic references to this (primarily Q 3:49 and Q 5:110) mean is that his mission, similar to that of any other prophet, was “to revive the living, not to resurrect the dead.”74 The people Jesus cured and brought back to life were dead in moral terms, not in the literal sense, as only in the hereafter will the dead be revived by God. In other words, for Rıza, prophets worked in the spiritual domain, contributing to people’s moral well-being and reviving their spirits, not curing their physical bodies or bringing the dead to life, which contradict natural laws and appear implausible to human reason.

Rıza also interpreted Q 19:29–30, which seem to describe Jesus talking in the cradle, differently, arguing that they did not refer to Jesus speaking while a newborn.75 In this case, he did not directly argue that it would be unreasonable, or attribute supernatural powers, to presume that an infant could speak. He rather sought evidence in the Qurʾān, arguing that as Mary is described as returning to her tribe from a distant place to which she had withdrawn (Q 19:22 and 19:27), Jesus must by then have been at least forty days old. He asserted that, although Q 19:29 states that Mary pointed to Jesus and people asked her how they could talk to this child, they meant ‘child’ not literally, but again figuratively, that is, this child whose infancy they remember. When Jesus said in response, “I am God’s servant; God has given me the Book, and made me a Prophet” (Q 19:30), it was not an infant speaking, but Jesus as an adult.76 Rıza emphasizes that all the verbs in this verse were conjugated in the past tense, not in the future tense; that is, Jesus was not talking as an infant who would in the future be a prophet but rather as a mature person who had already been made a prophet. In support of this argument, Rıza pointed out that in the next verse, Q 19:31, Jesus also cited the religious obligations assigned to him, such as almsgiving and prayer, and since God would not ask an infant to perform such tasks, Jesus must have speaking as an adult, or at least not as an infant. However, Rıza did not answer the question of why, when Mary pointed to the child, people expressed puzzlement at the idea of talking to a child in a cradle (Q 19:29).

Hakkı was more at ease with the idea of Jesus talking as an infant; he found it more acceptable intellectually and less in contradiction with contemporary scientific knowledge. He said that while it was difficult if not impossible to propose scientifically that Mary could conceive Jesus without sexual intercourse, a talking infant might be exceptional but not completely impossible.77

State responses to Rıza’s Qurʾān interpretation

A crucial aspect of the Ottoman regime was its highly organized and systematic censorship of printed publications. From the mid-nineteenth century onward, the late Ottoman Empire began to develop press codes, legal regulations, and state bodies responsible for inspecting books and periodicals. These state organs had jurisdiction over both religious and non-religious publications, but especially toward the end of the nineteenth century, with the flourishing of the printing of Qurʾān codices as well as articles in the press on Islamic topics, the Ottoman imperial state began to establish stronger control and approval mechanisms for printed religious texts and to assign jurisdiction over such matters to specific state organs.

One such agent was the aforementioned Tetkik-i Mesahif ve Müellefat-ı Şer’iyye (Council on the Inspection of Printed Qurʾāns and Islamic Religious Publications). This council was established in the 1910s by a merger of two separate councils dedicated to inspecting printed qurʾānic codices and Islamic books dating back to 1889. It became the overarching body to oversee the accuracy of printed religious books.78 The council’s jurisdiction was broadened over time to examine not just Islamic books but also articles on Islam in periodicals. At stake was not just the accuracy of printed texts, for instance the orthography of qurʾānic verses, but also the ideas they proposed, which in this case meant the meanings assigned to qurʾānic passages and ḥadīth. The essays on Jesus and Mary by Rıza, Ayni, and Hakkı drew the immediate attention of the council.

The council asserted that the second article penned by Rıza, responding to Ayni’s response to his first essay, contained articulations “contrary to the shari’ah and truth” (muğayir-i şeriat ve hakikat), and that these articles had the potential to “negatively influence [individuals’] Islamic thought(s)” (efkar-ı İslamiyeye su-i tesir edecek).79 In the eyes of the council, being published in a well-known newspaper enabled the authors to spread their interpretation of qurʾānic passages on Jesus to a wide reading public, and to exert an impact that the council identified as negative. The council seemed to use “shari’ah” in this context to denote common or established Islamic interpretations and teachings and “truth” to indicate a broader, more comprehensive veracity, one that might even contain some common elements between Islam and Christianity concerning the miraculous or virginal conception of Jesus. At any rate, what was most crucial for the council was its perception that these writings could have a negative influence on the Muslim public by, for instance, refuting commonly taught elements of the Islamic Jesus narrative.

However, in line with its typical working method, the council did not provide an extensive commentary on Rıza’s and Hakkı’s interpretations of the Qurʾān. Nor did it write a refutation discrediting their reading of the relevant qurʾānic passages. Rather, the council, similar to its censorship or disapproval of other periodical or book publications, limited its criticism of content only to the potentially negative and harmful influence of these Jesus articles. Again, as in other cases, it underscored the procedural mandate, which obligated every publisher to submit religious articles to the council’s approval. In its censorship or disapproval of religious publications, the council offered, only brief, if any, substantive explanation, and the negative influence or harm to Muslim religious understanding was one such short, categorical elucidation. The legal procedure of publishing religious books or articles was emphasized by the council in order to highlight the authority assigned to it in governing and regulating Islamic publications, regardless of judgments made by the council on their content, i.e., whether they were found permissible to be printed or not.80

The council reiterated Article 6 in the Printers’ Code, which obliged publishers to seek its approval before printing articles pertaining to religion (Islam) or containing qurʾānic verses and ḥadīth. The council emphasized that Article 6 applied to periodicals as well as books, and yet the essays about Jesus had been printed in the newspaper Tevhid-i Efkar without the council’s sanction. It wrote that the Directorate of the Press had informed all those concerned about this regulation and that it had been announced in newspapers as well, and therefore it had great “regret to observe” that some periodicals continued to print “the meaning and translation of qurʾānic verses and ḥadīth” without first presenting them to the council.81

The council followed up on the issue in correspondence with different state organs, which illustrates the legal ambiguities in state regulations concerning the oversight of press articles as well as the tensions between different state bodies. The council corresponded first with the Meşihat, the highest religious-bureaucratic governmental office under which it operated, so that the latter would write to the Ministry of the Interior to demand further inquiry into the incident. In January 1922, the same month the articles by Rıza and Ayni were printed in Tevhid-i Efkar, the Ministry of the Interior, in response to Meşihat, confirmed that it had written to the concerned state offices, including the Directorate of the Press, which announced to the newspapers’ administrative offices the decree that all articles with religious content were to be submitted to the council for approval.82 Yet the Directorate of the Press also indicated that Tevhid-i Efkar was not being printed at that time, and its license holder was not in Istanbul—circumstances that might have led to the newspaper’s ignorance of the regulation and failure to submit the articles to the council. However, the Directorate also claimed that the legal regulation did not make absolutely clear whether publishers needed the approval of the council before publication (to which the council continuously objected through its emphasis on the Advisory Council of State’s clarification of Article 6 in the Printers’ Code).83

The Press Directorate also emphasized some difficulties that had arisen because of the dual censorship mechanism that was in force in Istanbul, as the city was occupied by Allied forces after World War I and they established their own press censorship in addition to that of the Ottoman authorities. The Press Directorate gave the example of an incident in which an article had been published in Tevhid-i Efkar without the permission of the council but with the approval of the Allied forces’ censorship organ.84

The Press Directorate’s pronouncements on the incident disclose the presence of legal ambiguities, as well as complications and difficulties that emerged from the complex censorship system governing the Istanbul press. In this respect, even though the council emphasized its own jurisdiction in regulating articulations of Islam in newspapers and journals, in practice it was not able to fully enforce its dictates. After the council condemned the publication of Rıza’s essay without its approval, Hakkı’s piece appeared in the same newspaper only a month later, in February 1922. Hakkı’s essay had been submitted for approval, but it was printed in its original form despite the council’s disapproval.85

The council did not halt its attempts to assert control. Through its efforts, the Advisory Council of State reemphasized the relevance and validity of Article 6 of the Printers’ Code for periodicals, asserting that periodicals must submit their contents to the council. Because Hakkı’s article had been printed after this clarification, dated January 28, 1922, the council asked the Ministry of the Interior to punish Tevhid-i Efkar in order to set an example for other periodicals; the act of printing an article that had been deemed unsuitable, the council asserted, flouted the Ottoman government’s authority, as well as that of the caliph himself, and demonstrated contempt for the Meşihat and the Ministry of the Interior.86

The Ottoman failure to enforce regulations controlling the content of periodical publications (in this case specifically their religious content) cannot be attributed solely to the political circumstances of dual censorship by the Ottoman and Allied powers. It also reveals a gap between the laws and regulations and their enforcement. While Ottoman authorities, from the onset of Islamic publishing to the last days of the empire, sought to establish and maintain a fully functioning press control mechanism, intellectuals, scholars, and publishers both observed the censorship laws and sought to escape their control, in an ongoing process of bargaining, implementation, and counter-initiatives.

Some of the Ottoman administrative and legal regulatory mechanisms were maintained in the early decades of the Turkish Republic, which was born in the waning empire’s region of Anatolia, and the institutional apparatus that sought to control printed qurʾānic codices was one of them. Yet, both during the long centuries of the Ottoman Empire as well as in the shift from the Ottoman imperial to the Turkish republican period, what the state authorities considered religiously problematic and subject to censorship changed, and despite institutional continuities, the items censored during the late Ottoman and early Turkish republican period were not entirely the same.

In his complete publication of a Turkish translation of the Qurʾān in 1934, Rıza translated the sections from Sūrah 19 on Jesus as he had in the essays printed in Tevhid-i Efkar in 1921–1922. In the 1947 edition of the translation, Rıza included a more extended introduction, with five subsections, one of which was devoted to the question of prophetic narratives in the Qurʾān. Unlike in his earlier works, in his discussion of Jesus as a prophet in this 1947 work, he undertook a more comparative and inclusive analysis of different qurʾānic passages. As noted above, he also made more explicit and direct references to the translation of Mawlana Muhammad Ali as well as to Christian sources, primarily the Bible, in this work. In this edition, Rıza elaborated on Jesus’s natural death more than he had in his newspaper articles, while he still also emphasized his natural birth.87 It seems that the Republic-era censorship bodies did not find Rıza’s renderings of the qurʾānic Jesus narrative as problematic as the Ottoman Islamic print approval council had. Nonetheless, Rıza’s translation and interpretation of the qurʾānic Jesus passages, particularly regarding his birth and death, did not have a long-lasting and major impact on the Turkish religious-intellectual public.

Conclusion

The end of 1921 and the beginning of 1922, during which the three Ottoman intellectuals discussed the qurʾānic Jesus narratives, corresponds to a time of profound political conflict, chaos, and struggle in Istanbul. World War I and its aftermath, the occupation of Istanbul by Allied forces, and the subsequent transition from the Ottoman imperial regime to the Turkish Republic created massive demographic, socioeconomic, and political ruptures. These major changes were carried onto the pages of the newspapers and journals, which went through strong censorship by both the Allied powers as well as Ottoman and Turkish agents.

In the middle of this political turbulence, it seems, Rıza, Ayni, and Hakkı chose to engage in a different set of questions. This is not to suggest that their triangular disputation on Jesus in Tevhid-i Efkar was apolitical. On the contrary, although their disputation did not have any direct implications regarding the immediate, paramount political developments concerning state and regime formations, it was part of, and juxtaposed with, several contemporary political matters, ranging from Christian missionary and Orientalist writings on Islam to modern rationalist conceptions of religion.

Moreover, the disputation was an intellectual one, but it was created and circumscribed by material conditions and realities. First, their ideas were expressed in a medium that was made possible by the print technology and culture. These intellectuals reflected on the limits and potentialities of the Qurʾān as a printed and translated book. Muslim intellectual movements in different lands influenced their thoughts. And last but not least, the modern state with its bureaucratic administrative apparatus and legal-rational categories of legitimization had a major impact in regulating and circumscribing the terms of these intellectual discussions.

The triangular disputation did not have a long-lasting legacy in the Turkish intellectual or religio-political scenes; indeed, on the contrary, it remained buried in the pages of Tevhid-i Efkar and archival registries. Nor did Rıza’s Qurʾān translation have an impact on modern Turkish exegesis. Rıza’s interpretation of the qurʾānic Jesus narrative did not attain a noteworthy popularity among the Turkish Muslim public either during his lifetime or later. However, leaving aside the details of his understanding of the Jesus narrative, particularly his view that Jesus had a natural birth similar to any other human being (that is, Mary conceived Jesus through sexual intercourse), certain premises guiding his interpretation were prominent and influential in the 1920s as well as today.

The most prominent of these premises is a rationalized approach to the qurʾānic passages. Rıza underscored that a hierarchy of measures attesting to truth exists, and reason comes at the top. In other words, for him, the engagements with the Qurʾān and explanations provided in this respect vis-à-vis relevant passages need to be grounded in reason, comprehensible by the human mind, and in harmony with the rational capacities of human beings. Rational and natural were strongly affiliated in Rıza’s thinking, and that is why he underscored that Jesus had a natural birth, that is, one that the human mind can understand through the experience of the birth of other human beings. In his view, the qurʾānic narrative lacked details on certain dimensions of the subject, but it did not matter since the divine text could be inexplicit, but not irrational. The emphasis on the Qurʾān’s capacity to be understood by human agents promoted a direct connection between individual believers and the text, undermining the authorizing role of religious scholars in line with the prominent tendency of the period to criticize blind imitation. In Hakkı’s and Rıza’s interpretations, Jesus was humanized, but the point of that debate was not merely to refute Christian ideas on his divinity, but also to rationalize and naturalize Muslims’ understanding of qurʾānic themes and narratives.

About the author

Ayşe Polat is currently Assistant Professor at Istanbul 29 Mayis University. Polat completed her B.A. in Political Science and Sociology at Boğaziçi University, Istanbul (2002), and her M.A. at the University of Chicago (2005). She received her Ph.D. from the University of Chicago in Anthropology and Sociology of Religion in 2015. Her research interests lie in Islam and modernity, late Ottoman and Turkish Republican society and intellectual history, and the dynamics between religion and state, especially the bureaucratization of the religious field and surveillance of Islamic print and public morality.

Notes

1 Milaslı İsmail Hakkı also subsequently published a book on the subject, entitled Kuran’a Göre Hz. İsa’nın Babası [Jesus’s Father according to the Qurʾān] (Istanbul: Ankara Matbaası, 1934.)

2 For a brief, nonpolemical account of the qurʾānic and Islamic tradition’s conception of Jesus, see G. C. Anawati, “ʿĪsā,” Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.; Leiden: Brill, 1954–2005), s.v.

3 Born in Cairo to a family that had migrated from Anatolia, Ömer Rıza moved to Istanbul in 1915 and married the daughter of one of the most prominent Muslim intellectuals of his time, Mehmet Akif [Ersoy], thereby gaining introductions to important intellectual circles. In addition to his publishing and translation activities, Rıza became a deputy in parliament in 1950, engaged in developing Turkey’s relations with other Muslim countries. See Mustafa Uzun, “Ömer Rıza Doğrul,” in Türkiye diyanet vakfı İslam ansiklopedisi (Istanbul: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı, 1988–2014), 489–492.

4 Ayni was fluent in Arabic, Persian, and French. He worked as a bureaucrat in various positions at the Ministry of Education, held a governorship, and in 1914 started to teach at Istanbul University. See İsmail Arar, “Mehmet Ali Ayni,” in Türkiye diyanet vakfı İslam ansiklopedisi, 273–275.

5 After graduating from medical school, Hakkı worked as a health inspector in various cities. He was also an engaged public intellectual: he participated in the establishment of Yeşilay (Green Crescent Temperance Society), for instance, and supported the Ottoman-alphabet reform movement. See Müesser Özcan and Naki Bulut, “Tıp dışındaki farklı alanlarda da iz bırakan Muğlalı üç hekim,” Lokman Hekim Journal 3 (2013): 2–4. See also Resul Çatalbaş, “Milaslı Dr. İsmail Hakkı’nın hayatı, eserleri ve İslam ile ilgili görüşleri,” Artuklu Akademi Dergisi 1 (2014): 99–129.

6 Rıza published one of the first Turkish translations of the Qurʾān in Latin script during the early Turkish Republic in 1934. He titled his work Tanrı’nın buyruğu Kuran-ı Kerim tercüme ve tefsiri [The Decree of God: Translation and Exegesis of the Qurʾān] (Istanbul: Muallim Ahmet Halit Kitaphanesi, 1934; also Istanbul: Akşam Matbaası, 1934).

7 See, for instance, İskipli Mehmet Atıf, “Haml-i Meryem,” Mahfil 23 (Ramazan 1340 [April/May 1922]): 191–194. While not examined here, it should be pointed out that other essays or booklets on the topic had appeared right before 1922. For instance, see Muhammed Hilmi, Hz. İsa Aleyhissalam’ın babası var mı? [Did Jesus Have a Father?] (Istanbul: Evkaf-ı İslamiye Matbaası, 1338–1340 [1919–1921]).

8 The council’s archival record books examined in this study are currently available at the Meşihat Archive, located in the courtyard of the Istanbul Müftülüğü (Istanbul Muftiship), right by the Süleymaniye Mosque, Istanbul.

9 Although it is not a comprehensive list, the following works on modern Islamic thought may be cited: Albert Hourani, Arabic Thought in the Liberal Age, 1798–1939 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1962); John Voll, Islam, Continuity and Change in the Modern World (Essex: Longman, 1982); Daniel Brown, Rethinking Tradition in Modern Islamic Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996); Charles Kurzman, Modernist Islam, 1840–1940: A Sourcebook (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002).

10 Nikki Keddie deploys the concept of “self-strengthening” in her examination of a major modern Muslim intellectual. See Nikki R. Keddie, An Islamic Response to Imperialism: Political and Religious Writings of Sayyid Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983), 42.

11 Brett Wilson emphasizes the impact of Christian missionaries on Muslim translations of the Qurʾān. In his view, the missionaries’ “attacks on the Qur’an created a sense of urgency among Muslims to defend their sacred book.” See Brett Wilson, Translating the Qur’an in an Age of Nationalism: Print Culture and Modern Islam in Turkey (Oxford: Oxford University Press in Association with the Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2014), 22. It should be noted that Hakkı wrote a booklet specifically to respond to the Anglican Church’s questions about Islamic civilization, underlining the latter’s contribution to human civilization.

12 See Jane Smith and Yvonne Y. Haddad, “Virgin Mary in Islamic Tradition and Commentary,” Muslim World 79 (1989): 161-187, 175. In this regard, there is some evidence supporting Haddad and Smith’s argument in the Ottoman archival sources, too. Several years before the publication of these essays, in 1915 Tetkik-i Müellefat-ı Şerʿiyye and the Ministry of the Interior targeted pamphlets distributed about miracles and Mary in the Ottoman lands by American missionaries. Even though neither the records of Tetkik-i Müellefat-ı Şerʿiyye nor the archival documents contain much detail about the content of these booklets apart from asserting that they reject the prophethood of Muḥammad and create a negative political influence for the Ottoman caliphate by spreading ideas that confuse Muslim minds, it is plausible to think that some Ottoman scholars wrote essays addressing such missionary publications. Yet without reading these booklets and the works written in response to them, this is still speculative, requiring further research and evidence. See Meşihat Archive, Tetkik-i Müellefat-ı Şerʿiyye Defterleri 5/5, Genel No. 5293 (Nisan 29, 1331 [May 12, 1915]), 18 and Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi (Turkish Prime Ministry Ottoman Archive) (BOA) DH.EUM. MTK 80/29 (Nisan 16, 1331 [April 29, 1915]).

13 Rıza, Kuran-ı Kerim tercüme ve tefsiri (Istanbul: Akşam Matbaası, 1934), 183.

14 For a comparative examination of the interpretation of miracles in contemporary Islamic and Christian thought, see Isra Yazicioglu, Understanding the Qur’anic Miracle Stories in the Modern Age (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2013). Although not specifically about miracles, for an overall depiction of the religion versus science dilemma among late Ottoman thinkers, see Şükrü Hanioğlu, “Blueprints for a Future Society: Late Ottoman Materialists on Science, Religion, and Art,” in Elizabeth Özdalga (ed.), Late Ottoman Society: The Intellectual Legacy (London: Routledge Curzon, 2005).

15 Rıza’s interest in India and Pakistan continued in subsequent years as well, as is evident in the fact that he was elected president of the Turkish-Pakistan Cultural Society in 1950. See Uzun, “Ömer Rıza,” 489.

16 See Wilfred Cantwell Smith, “Aḥmadiyya,” Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.; Brill, 1954–2005), s.v.

17 See Azmi Özcan, “Muhammed Ali Lahuri,” in Türkiye diyanet vakfı İslam ansiklopedisi (Istanbul: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı, 1988–2014), 500–502.

18 For a list of Muhammad Ali’s publications, see ibid., 501–502.

19 Ibid., 501.

20 Ali Akpınar, “Ömer Rıza Doğrul (1893–1952) ve tefsire katkısı,” Cumhuriyet Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi 6 (2002): 17–36, 33–34.

21 Rıza, “Mevlevi Muhammed Ali ve Himmet-i Meşkuresi,” Sebilürreşad 18, no. 446 (Teşrinievvel 30, 1335 [October 30, 1919]): 44–45. While Muhammad Ali’s English translation of the Qurʾān is often considered to be the first complete one undertaken by a Muslim, Azmi Özcan points out that Muhammad Abdulhakim Khan’s 1905 translation predates his 1913 one (“Muhammed Ali Lahuri,” 501).

22 Cited in Ali Akpınar, “Ömer Rıza,” 33.

23 Ibid.

24 Rıza, Kuran-ı Kerim tercüme, 924.

25 Ömer Rıza, “Milad-ı İsa aleyhisselam,” Tevhid-i Efkar, Kanunievvel 26, 1337 [December 26, 1921], 3.

26 Ibid.

27 Mehmet Ali Ayni, “Milad-ı İsa meselesi,” Tevhid-i Efkar, Kanunisani 4, 1338 [January 4, 1922], 2.

28 Ibid. Emphasis mine.

29 Ömer Rıza, “Milad-ı İsa Meselesi, Ömer Rıza Bey’in Mehmed Ali Ayni Bey’e Cevabı,” Tevhid-i Efkar, Kanunisani 6, 1338 [January 6, 1922], 3.

30 Ibid.

31 Milaslı İsmail Hakkı, “Haml-i Meryem meselesi,” Tevhid-i Efkar, Şubat 7, 1338 [February 7, 1922], 3.

32 Ibid.

33 Although Hakkı does not explicitly refer to it, this distinction he draws is similar to the traditional dichotomy set between qurʾānic muḥkamāt and mutashābihāt verses in which the former are considered to have absolutely precise and clear meanings and the latter to be unspecific, to have the capacity to be interpreted differently, which is derived from Q Ᾱl ʿImrān 3:7.

34 Hakkı, “Haml-i Meryem,” 3.

35 Ibid.

36 Ibid.

37 See Ercan Şen, “Milaslı İsmail Hakkı’nın (1870–1938) Kur’an tercümesine dair bir risalesi,” Gaziosmanpaşa Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi 1 (2013): 261–286, 274–276.

38 Hakkı, “Haml-i Meryem,” 3.

39 Ibid.

40 For a brief account of the beginning of the Qurʾān translation debate in the late Ottoman Empire and early Turkish Republic, see Wilson, Translating the Qur’an, 104–111; also Amit Bein, Ottoman Ulema, Turkish Republic: Agents of Change and Guardians of Tradition (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011), 116–123.

41 Wilson, Translating the Qur’an, 2; on vernacular commentaries, see 84–111.

42 For translation works in the early Turkish Republic and the subsequent state-sponsored Qurʾān translation project, see ibid., 161–180, 221–245.

43 See Ayşe Polat, “Subject to Approval Sanction and Censure in Ottoman Istanbul

(1889–1923),” (Ph.D. diss., University of Chicago, 2015).

44 Ayni, “Milad-ı İsa meselesi,” 2.

45 Rıza, “Milad-ı İsa meselesi,” 3.

46 Geoffrey Parrinder, Jesus in the Qur’an (Rockport, MA: Oneworld, 1995), 67.

47 In these two almost identical verses, there is only a difference in pronouns, one referring to “her” and the other to “it” respectively, as Q 21:91 says “We breathed into her some of our spirit,” and Q 66:12 says “We breathed into it some of our spirit.” The pronoun “it” is interpreted as Mary’s vagina in some of the commentaries. See Michael Sells, “Spirit,” Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān (Leiden: Brill, 2001–2006), s.v. (2005).

48 Rıza, “Milad-ı İsa meselesi,” 3.

50 Rıza, “Milad-ı İsa meselesi,” 3.

51 Q 4:157 is rendered the same way in multiple translations: “they did not kill him [Jesus], nor did they crucify him, but it appeared so to them.”

52 On the topic of the death of Jesus, see Parrinder, Jesus in the Qur’an, 105–121; Neal Robinson, Christ in Islam and Christianity: Representation of Jesus in the Qur’an and the Classical Muslim Commentaries (New York: State University of New York Press, 1991), 117–140 and 180–185; and for a number of Muslim intellectuals’ ideas on the crucifixion, see Todd Lawson, The Crucifixion and the Qur’an: A Study in the History of Muslim Thought (Oxford: Oneworld, 2009), 115–142.

53 Rıza, “Milad-ı İsa meselesi,” 3.

54 Rıza, “Milad-ı İsa aleyhisselam,” 3.

55 Rıza, “Milad-ı İsa meselesi,” 3.

56 Ibid.

57 Rıza, “Milad-ı İsa aleyhisselam,” 3.

58 In his reading of the Jesus story, Rıza did not make any comparative intertextual references to biblical narratives about Jesus. However, only regarding Q 19:32—in which Jesus is ordered to be respectful and dutiful to his mother (no reference appears to his father)—he asserted that this is a qurʾānic response to the Gospel of Matthew, in which Jesus is by some interpretations portrayed as speaking negatively about his mother. Rıza wrote that the incident is found in Matt 12:28, but the correct reference might be Matt 12:46–50. In any case, according to Rıza, the Qurʾān’s mention of only Jesus’s mother in Q 19:32 has nothing to do with his conception without a father.

59 Rıza, “Milad-ı İsa meselesi,” 3.

60 Ibid.

61 For a brief discussion of the notion of spirit in the Qurʾān in terms of its semantic features, see Michael Sells, “Sound, Spirit, and Gender in Sūrat al-Qadr,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 111 (1991): 239–259.

62 In some of the classical qurʾānic commentaries, the spirit in Q 19:21 is identified with the angel Gabriel, too, and the commentators discuss the ways the angel could approach Mary to conceive the child, which ranges from the idea that the angel blew in “the fold of her covering until the breath reached her womb,” to “causing the spirit to enter through her mouth.” See Smith and Haddad, “Virgin Mary,” 167. Rıza does not provide any details concerning how he thinks the angel physically helped Mary conceive a child.