PDF

Download

Citations

Click and drag then release to select a passage to cite.

Annotations

How to submit annotations to Mizan Journal articles:

your work is published.

Search within

Qiṣaṣ al-Anbiyāʾ as Genre and Discourse

From the Qurʾān to Elijah Muhammad

Image

Audio

Video

Chart or Graph

Qiṣaṣ al-Anbiyāʾ as Genre and Discourse

From the Qurʾān to Elijah Muhammad

Introduction: defining the field and its object of study

The study of qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, the Islamic tales of the prophets, has a well-established pedigree in the Western academy. This issue of Mizan: Journal for the Study of Muslim Societies and Civilizations coincides with the fiftieth anniversary of Tilman Nagel’s 1967 thesis “Die Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ: ein Beitrag zur arabischen Literaturgeschichte,” a groundbreaking contribution that has played a seminal role in the modern study of the subject.1 The papers we present here were originally delivered at a conference convened in Naples in fall 2015 in anticipation of this important occasion, “Islamic Stories of the Prophets: Semantics, Discourse, and Genre” (October 14–15, 2015).

Nagel’s work provided a solid foundation for future research, but it is one that subsequent scholars have built upon somewhat irregularly, and much work remains to be done. Unfortunately, the study of qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ per se has not flourished in the last couple of decades with quite the same vigor as the study of Qurʾān and tafsīr, though the study of qiṣaṣ has surely benefitted, at least indirectly, from the extremely energetic expansion of both of those fields in recent years. In this introduction, we seek to evaluate the state of the field of qiṣaṣ studies, locate the individual contributions to the issue in it, and point the way forward to possible future trajectories of development.2

Nagel’s thesis discusses the ancient roots of qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ among early traditionists, as well as highlighting important literary works in which this early (or allegedly early) material is gathered. He goes on to delineate the literary genre of qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ proper, discussing major works carrying this title or something similar such as mubtadaʾ, badʾ al-khalq, and so forth. Here he draws an interesting distinction between more scholarly representatives of the genre and texts of a more “popular” nature; this distinction has been particularly influential on many subsequent discussions of the material.3

Nagel’s thesis represents the first attempt to delineate the contours of qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ both as a genre and a broader tradition in a serious and methodical way. However, his work could not have been undertaken without that of a number of significant predecessors that helped pave the way before him, enabling his more systematic approach. Lidzbarski’s pioneering thesis of 1893 has limited impact today due to being written in Latin, but exerted a significant impact on the fledgling field in its day; the emphasis here, as in many other studies of the late nineteenth and first half of the twentieth century, is on cataloguing influences; the breadth of the sources adduced, not only in Arabic and Hebrew but also Syriac and Ethiopic (thus directing attention to medieval Christian as well as Jewish comparanda for Islamic qiṣaṣ traditions), is noteworthy.4 Despite its evident shortcomings as a critical edition, Eisenberg’s publication of the major qiṣaṣ of Abū Jaʿfar Muḥammad b. ʿAbd Allāh al-Kisāʾī (ca. 6th/12th c.) in 1922–1923, the subject of his doctoral dissertation of 1898, allowed this important work to gain a significant scholarly audience.5 Though its flaws are evident today, Sidersky’s study Les Origines des Légendes Musulmanes was noteworthy in its time for making a serious and wide-ranging attempt to untangle the densely intertwined threads of Qurʾān, midrash, and later Islamic tradition as presented not only in tafsīr but in the chronicle of Abū Jaʿfar Muḥammad b. Jarīr al-Ṭabarī (d. 310/923) and the qiṣaṣ collections of Kisāʾī and Abū Isḥāq Aḥmad b. Muḥammad al-Thaʿlabī (d. 427/1035).6 This is to say nothing of the numerous works published since the time of Abraham Geiger (d. 1874) specifically focusing upon the Jewish and Christian “influences” on the Qurʾān, which of necessity contain much speculation on the background and parallels to the narratives concerning the biblical prophets in scripture. Here pride of place must certainly go to two titanically important works of German scholarship, Josef Horovitz’s Koranische Untersuchungen and Heinrich Speyer’s Die biblischen Erzählungen im Koran, arguably the most important contributions to the field inaugurated by Geiger’s 1832 Preisschrift “Was hat Mohamed aus dem Judenthume aufgenommen?”7

Nagel’s thesis has shaped the contemporary study of qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ in numerous ways. Perhaps the most obvious and explicit contribution his work made was to draw greater attention to critical works of the qiṣaṣ genre such as those of Thaʿlabī and Ibn Muṭarrif al-Ṭarafī (d. 454/1062). It is important to note, however, that this focus on classic specimens of the genre was balanced by Nagel’s keen appreciation of the larger tradition that crystallized in the specific works that constituted that genre, a point we will take up again momentarily. As noted above, Nagel—and other scholars who addressed the subject soon after the publication of his thesis—examined discrete texts carrying the title of qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ or the like.8 They considered such questions as how this literary genre related to others, how it coalesced out of other fields such as ḥadīth, exegesis, and historiography, and other issues of a literary-historical nature. Despite the decades of interest in this field that preceded Nagel, he and his contemporaries still had significant work to do of a fundamentally bibliographic and prosopographic nature, to say nothing of striving to conceptualize the field and represent this material’s true significance in Islamic culture adequately.

As Nagel explicitly notes in the address he has contributed to this journal issue (“Achieving an Islamic Interpretation of Qiṣaṣ al-Anbiyāʾ”), when he originally embarked upon his research on qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, he rapidly ascertained that what was most necessary was not a simple cataloging of traditions “borrowed” and adapted from Jewish and Christian sources and subsequently transmitted in the qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ literature, but rather a deeper understanding of what is properly “Islamic” about the Islamic tales of the prophets in the first place.9 That there are larger implications of qiṣaṣ as a realm of interest to Muslim traditionists and authors, particularly of a political or ideological nature, is a point that is perhaps too easily lost. When speaking of “biblical” prophets in Islamic tradition (a subject taken up most often vis-à-vis the Qurʾān, the foundation of the tradition), the tendency to catalogue “borrowings” and discern “influences” without adopting a more nuanced understanding of processes of adaptation and reinterpretation sometimes still predominates.

The difficulties involved in approaching and characterizing this material, and for that matter defining or circumscribing qiṣaṣ as an object of study, become evident when we examine scholarship that actually investigates the portrayal of specific prophetic figures in Islamic tradition.10 Many of these figures have been subjects of significant scholarly treatments. These inquiries almost always start by examining the qurʾānic basis of Islamic understandings of the figure or figures in question, a natural place to begin given the foundational role of the Qurʾān in shaping Muslim understandings of the pre-Islamic prophets.11 They then typically proceed to explore biblical, Jewish, and Christian parallels, precursors, and “influences,” often laying particular emphasis on one or another body of late antique literature as a likely or possible vector through which older themes, concepts, and images were transmitted. Finally, they survey, with greater or lesser degrees of comprehensiveness, what Muslim traditionists and authors said and the narratives they transmitted about the figure in question. The precursors to the Qurʾān and the Nachleben of themes and narrative complexes in later Muslim literature may receive greater or lesser emphasis depending on the inclination of the author or the purpose of the study; understandably enough, some scholars gravitate more to the Qurʾān as the foundation of the tradition, while others orient themselves forward in looking at the development of the prophets in Islamic literature and tradition.

There have been a number of exemplary studies on specific figures over the decades since Nagel’s work, though they have been few and far between. Likewise, it is worth noting that over the last twenty years many new editions of qiṣaṣ works have appeared, although they have yet to have a significant impact on scholarship.12

Studies focusing on prophetic figures in Islam range from antediluvian history (Schöck on Adam, Bork-Qaysieh on Cain and Abel, and Awn and Bodman on Satan/Iblis), to the era of the patriarchs (Firestone and Lowin on Abraham), to that of the Exodus (Wheeler on Moses), the Israelite monarchy and the time of the prophets (Mohammed on David, Lassner on Solomon and Sheba, and Déclais on David, Isaiah, and Job) and finally Jesus (Lawson, Khalidi, and numerous others).13 These studies may focus on one episode from the life of a specific prophet or on their portrayal more broadly. Most of them draw on a range of material, though often privileging classic historical or especially exegetical sources (e.g., Ṭabarī).

Observing this broad pattern, we might note that if one wanted to write a diachronic study of narratives about a specific prophetic figure in Islam, there are at least a dozen major texts one could readily consult to get an overview of what Muslims have said, written, and thought about Adam, Noah, Moses, Jesus, and the like. Yet the core texts in which one would seek this material —at least if one were inclined to follow established scholarly precedent—are certainly not all works commonly recognized as being in the genre of qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ per se; in fact, usually very few of them are. The most wide-ranging works on the biblical prophets in Islam will certainly incorporate material from classic works in the genre, though these works appear as only part of the literary corpus upon which they draw. Actual works in the genre are seldom if ever given pride of place, and scholarly treatments with a particular emphasis on exegesis may omit them from the discussion completely.

Thus, upon reflection, the selective reliance of the scholarly literature on the prophets in Islam on qiṣaṣ texts appears peculiar: there is a whole corpus of sources explicitly devoted to the tales of the prophets in Islam that scholarly investigations of prophets in Islam tend to underutilize or avoid entirely. Likewise, despite the decades since Nagel’s work, the study of the genre of qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ per se has been rather overlooked. Marianna Klar’s Interpreting al-Thaʿlabī’s Tales of the Prophets: Temptation, Responsibility and Loss remains the only monograph-level study of Thaʿlabī’s literary strategies in his qiṣaṣ, considering both the author’s signal concerns and comparing his material with that collected in a variety of other sources.14 While Kisāʾī’s work remains neglected in this regard, at least the production of new translations of his qiṣaṣ, as with those of the ʿArāʾis of Thaʿlabī, may serve to enable a broader audience to access the text and delve into its riches.15

What this trend in scholarship points to is the rather anomalous nature of the qiṣaṣ genre as a whole and the ambiguous relationship it has with the larger literary evidence for Islamic understandings and portrayals of the prophets. Many important texts in the history of the genre are simply no longer extant, and even printed editions may not be widely available. Other important sources of qiṣaṣ material—in fact, some of those most commonly cited as such sources, such as the tafsīr and chronicle of Ṭabarī—are not entitled qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ or structured around the succession of prophets at all, but rather represent other literary genres in which significant amounts of such material are found, especially exegesis and history.16

The preference given to exegetical literature in studies of this sort—which, as noted above, is often entirely explicit—is understandable given the centrality of the Qurʾān in establishing the Muslim view of various prophetic figures.17 It seems likely that many narratives about the prophets were generated in explanation of and expansion upon the Qurʾān’s numerous references to these characters. Further, since the time in which scholars such as Nagel, Pauliny, and Vajda first discussed this material, there has been a tendency to see the roots of qiṣaṣ as anchored in the sermons and predispositions of the quṣṣāṣ or preachers of the early Islamic milieu, with their preaching and storytelling consisting largely of elaboration upon qurʾānic stories.18

As Thaʿlabī himself noted in the introduction to his qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, the qiṣaṣ of the Qurʾān were meant as edification and admonition for Muḥammad and his followers.19 Not only was qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ built on the foundation of qiṣaṣ al-Qurʾān, but it is clear that qurʾānic paradigms, a parenetic approach to history, informed much historical reflection in the early Islamic community.20 Historiography as well as qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ may thus be seen as an essentially para-qurʾānic enterprise, as is plainly evident from the amount of material on the pre-Islamic prophets and their communities found in major chronicles.21

The presupposition that much qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ was actually derived from tafsīr explains the prominent, even predominant, tendency to turn to commentary literature as providing the main literary corpus of first resort in modern studies on biblical prophets in Islamic literature. Further, unsurprisingly, classical Sunni sources are privileged as exemplars of that literature, as they are in studies of Islamic exegesis more generally. Many other sources of importance have thus been sidelined in contemporary scholarship, particularly adab works, minor or local histories, and numerous genres of Shi’i texts. This is to say nothing of the general neglect of a variety of post-classical works, excluded or dismissed because they are supposedly derivative, despite containing unique traditions or novel perspectives on older material.

Among commonly cited works in studies of this sort, Thaʿlabī and Kisāʾī are undoubtedly the representatives of the qiṣaṣ genre cited most often.22 Admittedly, students and scholars of qiṣaṣ do not have ready recourse to a particularly sizeable corpus of classical texts as exemplars of the genre, which serves to reinforce the predisposition to draw upon tafsīr, a genre in which works are vastly more abundant. Even so, there may be other contributing factors to the underemployment of other qiṣaṣ works in studies of particular prophets—or discussions of the larger genre—such as the perception that these sources are late, “popular,” or contain nothing substantial that is not found in the exegetical literature or in the classic works of Kisāʾī and Thaʿlabī.

Further, and even more striking, is the lack of serious extended investigations of these canonical works, as already noted. It was long ago postulated by Nagel that Thaʿlabī’s qiṣaṣ is the more ‘orthodox’ and scholarly distillation of this material while Kisāʾī’s work—still of uncertain provenance—represents a more popular presentation of it. Whether or not this is true, the relationship of these works to their milieus, to other textual-traditional strands, and to each other (and in Thaʿlabī’s case, the relationship between his tafsīr and qiṣaṣ) are all areas of inquiry that remain ripe for exploration.

The corpus of works making up the qiṣaṣ genre often seems to be in something of a state of disarray, with important texts only partially extant or recoverable only through later quotations. The preeminent example is the Kitāb al-Mubtadaʾ of Ibn Isḥāq (d. 767), which, though originally the first text in a tripartite cycle of works, was probably the first solidly dateable collection of qiṣaṣ material. A kind of English reconstruction of the text on the basis of later citations of Ibn Isḥāq’s transmitted material has been available for almost thirty years in the guise of Gordon Newby’s The Making of the Last Prophet; the reception of this work has been mixed due to ambivalence about Newby’s overconfidence in recovering Ibn Isḥāq’s material from later sources.23 Other important texts are unpublished, such as the early and apparently influential work of Isḥāq b. Bishr, extant in only one partial manuscript and so still conspicuously underutilized because of its inaccessibility; a critical edition of this work is a clear desideratum.24 Some other works of significance have been published in scholarly editions, but are relatively inaccessible and so underemployed. This is the case with the works of ʿUmārah b. Wathīmah (d. 902) and Ṭarafī.25 Likewise, despite being published twenty years ago, the major qiṣaṣ work of Rabghūzī (d. after 710/1331) remains known only to specialists, no doubt due to its relatively late date and its relatively obscure linguistic background, being one of few surviving witnesses to Khwarezmian Turkish.26

It is surely ironic that in the modern Islamic world, the two most widely available qiṣaṣ texts stand in many ways at totally opposite ends of the ideological spectrum of Sunnism. Thaʿlabī’s ʿArāʾis al-majālis is regularly reprinted and has long been a very successful and widely disseminated representative of the qiṣaṣ genre, despite the fact that the tafsīr of Thaʿlabī has historically been sidelined by Sunnis.27 Meanwhile, the other widely available exemplar of the genre—probably more readily available than even Thaʿlabī’s text, repeatedly republished as well as being translated into other languages—is, in fact, a highly problematic representative of it. This is the qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ of Ibn Kathīr (d. 774/1373), which was produced during the modern period by extracting the relevant material from his world chronicle, Al-Bidāyah wa’l-nihāyah. One is struck by the fact that this popular qiṣaṣ is an artificial text derived from the work of an author whose view of the qiṣaṣ tradition was very often ambivalent, if not explicitly censorious, due to its purported function as a vehicle for isrāʾīliyyāt.28

What may we conclude from all this? It is obviously important that the trend towards publication of early, classical, and post-classical works in the genre should continue, and there is clearly a need for accessible editions and translations. The production of critical editions and translations is a form of scholarly activity that is perhaps less popular than it once was, likely because it seems to seldom be appreciated or rewarded adequately by academic institutions. However, advances in digital text representation and publication counterbalance this to some degree. Further, the translation of works in a variety of genres of Arabic and other Islamicate literatures is currently undergoing something of a renaissance in English-speaking countries at least, judging by the number of important series in which such translations are being regularly produced. At any rate, simply making more texts of the qiṣaṣ genre available will greatly increase the likelihood of their being incorporated into scholarly discussions and perhaps even attract dissertation- or monograph-level attention.

There is a broader conclusion to be drawn from all this, however. The unusual nature of our canon of qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ works, the distribution of relevant material across genres, and the general modus operandi of major scholarship on prophetic figures demonstrates, in a salutary way, the arbitrariness of the genre itself and its blurry boundaries. That is, without a significant corpus of exempla in the genre per se, but with a corpus of ancillary works that actually seem to provide a great deal of material relevant to the historical development of traditions about the prophets in Islam, we must recognize that qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ is only misleadingly or imperfectly characterized as a genre at all. It might more accurately be characterized as a discourse—one that has particular characteristics and reflects certain ideological tendencies, but far surpasses the bounds of any specific literary genre in which it is manifest, including that of qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ itself.29 This brings us full circle back to Nagel’s thesis, in which—as noted before—we see a dynamic tension between qiṣaṣ as a genre and qiṣaṣ as a broader tradition.

A clear parallel to this is found in late antique Christian reflection on and use of the figures of the Israelite prophets. To understand how the biblical prophets were conceived and memorialized in Christian culture in this period, we would have recourse to material from numerous genres, including—and especially—biblical commentary and hagiography. There are precursors and parallels to actual qiṣaṣ works in late antique and medieval Christian culture, e.g., the Byzantine Lives of the Prophets, but to understand the larger narrative, discursive, and ideological parameters of Christian appropriation of these Israelite figures, we would have to go far beyond the bounds of texts like this one that were specifically devoted to them.30 This, we would argue, is the way in which Islamic tales of the prophets should similarly be approached, conceptualized as a discourse as well as a genre or discrete corpus.

The origins and ideology of qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ: the case of Ibn Isḥāq

Ibn Isḥāq’s Kitāb al-Mubtadaʾ, arguably the earliest text that can be called a work of qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, demonstrates the importance of a nuanced understanding of what qiṣaṣ is both as a genre and as a discourse right at the inception of the tradition. Ibn Isḥāq did not set out to write a qiṣaṣ work for its own sake, out of purely literary or antiquarian interest.31 Rather, Ibn Isḥāq collected traditions on the prophets and incorporated them into a text that was part of a larger tripartite structure reflecting a complex historiographic, ideological, and religious agenda. Ibn Isḥāq is typically credited as the author of the first major biography of Muḥammad, but his intention was more ambitious. The extant version of his Al-Sīrah al-nabawiyyah, known primarily through the recension of Ibn Hishām (d. 218/833), incorporates material from two of the three parts of Ibn Isḥāq’s magnum opus, the initiation of the Prophet’s mission in Mecca (the mabʿath) and the raids and military campaigns that established the early Islamic state under his leadership (the maghāzī).

Ibn Hishām’s edition of Ibn Isḥāq’s work omits the third component of this programmatic work, the section (or possibly originally discrete work) called the mubtadaʾ, which appears to have been a prologue to the life of Muḥammad consisting of episodes from the lives of the pre-Islamic prophets.32 These episodes both foreshadowed elements of Muḥammad’s life and mission and established that mission as the final link in a chain of divine guidance going back to Adam, validating Islam through a vivid portrayal of the continuity of Muḥammad’s mission with Israelite precursors in particular.33

By excising the mubtadaʾ from what became the most authoritative account of the life of the Prophet, Ibn Hishām quite arguably severed the Sīrah from the context that endowed it with its most significant meaning in the early Islamic milieu. As the work of Wansbrough demonstrates, prophetic biography was critical in embedding the emergence of Islam in a larger hierohistorical schema or Heilsgeschichte, as the central event in the divinely ordained unfolding of human history.34 By prefacing the account of the mission of Muḥammad with accounts of his prophetic precursors, particularly Israelite precursors, Ibn Isḥāq was deliberately and overtly appropriating biblical history as part of the sequence of events culminating in the revelation of the Qurʾān and the emergence of the Muslim ummah. Augmenting the basic perspective already adumbrated in the Qurʾān itself, this approach further naturalized the idea that Islam, rather than Judaism or Christianity, was the teleological endpoint of God’s long history of interaction with humanity, particularly as anchored in and mediated through revelation.

As Newby has shown, this new hierohistorical scheme was in direct competition with those of Jews and Christians. The supersessionist gesture of appropriating previous dispensations as parts of Islam’s own history actually served to assimilate a well-established mode through which Christians approached history themselves; it also decisively reduced both Judaism and Christianity to mere prologues to the revelation of Islam.35 Viewed this way, the broader qiṣaṣ tradition is the complement to the tradition of Muslim critique of Judaism and the Bible surveyed in Adang’s magisterial study of the topic.36 Polemic, criticism, and gestures of delegitimation are explicit in the latter, but only implicit in the former.

Ibn Isḥāq’s students and transmitters edited his work down into a more manageable size, thus shearing the mubtadaʾ from its original context.37 However, other authors and traditionists continued the work of collecting and arranging material on this subject, keeping Ibn Isḥāq’s supersessionist vision alive. For example, it is worth noting that the unpublished Qiṣaṣ al-Qurʾān of Abū’l-Ḥasan al-Hayṣam b. Muḥammad al-Būshanjī (d. 467/1075) of Nishapur presents episodes from the lives of the pre-Islamic prophets in sequence in the first part of the book and then an account of the life of Muḥammad in the second. Structurally speaking, this is the equivalent of Ibn Isḥāq’s Al-Sīrah al-nabawiyyah in condensed form.38 If we recall the ideological implications of the mubtadaʾ not just as a work but as an historiographic concept—based fundamentally on the premise that the history of the Israelite prophets points ineluctably forward to the coming of Muḥammad and Islam—the ideological nature of the discourse on qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ becomes transparent even when the linkages between the pre-Islamic prophets and Muḥammad, the Seal of the Prophets and final messenger, remain only implicit.39

At its core, qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ represents the transformation of the literary artifacts and symbols of an older culture. Once reflecting that older culture’s distinctive historical context, dispositions, and concerns, this material was subsequently appropriated, transmitted, translated, preserved, augmented, and ultimately reoriented and transformed as it was assimilated to a new culture’s historical context, dispositions, and concerns. Thus, in some sense, the place of qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ in formative Islam may be thought to be analogous to that of the Greek classics in imperial Rome.40 Just as the literary remains of classical Greek culture became a significant part of Roman culture and a fundamental part of Roman self-presentation, self-conception, and political legitimation, so too did the literary remains of the ahl al-kitāb, the Israelite cultural legacy as received and reinterpreted by both Jews and Christians, become a significant part of the culture of Islam and a fundamental part of Muslim self-presentation, self-conception, and political legitimation. Despite this integral dependence and thoroughgoing debt, Rome systematically demolished and absorbed many of the Greek polities in which what became the classical tradition had originally flourished; likewise, under similar circumstances, the early Islamic polity conquered, subordinated, and absorbed the Jewish and Christian communities that originally furnished Islam with many of its basic cultural components.

The Romans positioned themselves as the heirs to the Greeks both through narratives of continuity and succession (e.g., the Aeneid) and through direct assimilation of Greek traditions and literature, incorporating them as their own patrimony. As an imperial culture, the caliphate expressed itself as the successor to the Prophet, but also articulated literary forms like qiṣaṣ that ultimately positioned Islam as the successor to Israel. This was accomplished in part by mimicking a similar discourse in imperial Christianity through which the legacy of Israel was selectively constructed and represented in such a way as to appropriate the patriarchs, prophets, and kings as symbolic forebears while disinheriting the Jews as rival claimants to that legacy.

Thus, the corpus of traditions we might label qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ represents the literary remains of this process of transference and assimilation, as they often consist of Arabized and Islamicized versions of kitābī narratives of the prophets. More to the point, however, qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ is also an enduring testimony to the central animating concept that enabled the establishment of Islamic dominion over Jews and Christians—the basis of the claim of succession that presented the caliphate as the vehicle for the new dispensation that would replace Judaism and Christianity, giving religious and cultural meaning to what would otherwise have been a mere military takeover, with one occupying elite simply exchanged for another.

It is clear that qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ is at least partially modeled upon and appropriates a Christian historical habitus with significant precursors in authors like Eusebius, who makes some of the earliest ideologically coherent statements valorizing Christian empire as inheritor of the legacy not only of Christ but of the Israelite kingdoms and prophetic tradition, building on older Christian articulations of the Old Testament as proto-Christian truth.41 Common to both imperial Christianity and Islam is the deliberate attempt to present the patriarchs and kings of Israel as prophets and sources of guidance (that is, imāms) while dismissing the Jews as marginal, heretical, and irrelevant.

Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ and qiṣaṣ al-Qurʾān

This adaptation of a critical instrument of supersession from Christianity was not initiated by early Islamic traditionists or authors like Ibn Isḥāq (although the question of his particular familiarity with Christian culture has yet to be thoroughly explored). Rather, the adaptation of this supersessionist tool occurs already in the Qurʾān, and so one might say that the attempt to appropriate the legacy of Israel and reorient the prophetic and covenantal legacy so that it culminates with a new community with roots in Arabia occurred at the time of the foundation of Islam itself. As has often been remarked, the Qurʾān most typically employs the literary technique of reducing narratives about the pre-Islamic prophets to their most basic outlines, compressing and condensing them so as to conform to a basic template that makes the parallels between their missions and that of the qurʾānic prophet evident, though usually implicit.

An obvious example is Sūrat al-Shuʿarāʾ (Q 26), which presents accounts of the major events associated with the missions of qurʾānic-biblical prophets like Moses, Noah, and Lot alongside similar events linked to the careers of messengers sent to ʿᾹd, Thamūd, and the ‘forest-dwellers.’ The chapter is rigorously schematic, with many of the particularities of the prophetic narratives as known from pre-Islamic biblical tradition stripped away and the episodes boiled down to their essence. The individuality of particular prophets, the idiosyncrasies of their portrayals, are irrelevant in the larger hierohistorical scheme constructed by the qurʾānic author.

One’s conception of the relationship between the schematized proto-qiṣaṣ al-Qurʾān and the Qurʾān’s revelatory context depends upon one’s perspective regarding the problem of the historical Muḥammad. For the early Orientalists, it was natural to read qurʾānic references to the missions of the biblical prophets as admonitions to the Prophet’s opponents and messages of consolation to Muhammad and his followers. The dominant hermeneutic brought to these qurʾānic stories was thus biographical: the thematic choices reflected in qurʾānic retellings are determined by specific events in the life of the community or the Prophet himself.

This approach fell out of fashion for a number of reasons, especially due to the advent of revisionism: insofar as scholars came to have serious doubts that Islamic tradition had conserved and transmitted much information that could be judged to be accurate and reliable in modern historical terms, this skepticism also called into question the appropriateness of using sīrah as an exegetical tool for explaining and contextualizing references in the Qurʾān.42 This applies not only to actual historical events to which the Qurʾān supposedly alludes, but also the larger biographical frame that would allow one to infer the deeper significance of the particular narrative choices that inform qurʾānic retellings of episodes from the lives of the pre-Islamic prophets. That is, discerning echoes of the mission of Muḥammad in narrations of events in the lives of Abraham or Moses or Jesus becomes an uncertain enterprise if one is skeptical that the Qurʾān actually refers to events in the mission of Muḥammad as we know them from Islamic tradition.

Despite the fact that such skepticism has now become reflexive in many quarters in the contemporary study of the Qurʾān, a hermeneutic of reading Qurʾān through the lens of prophetic biography has recently been revived. An important forerunner of this tendency is Walid Saleh’s 2006 article on the story of Saul in Q Baqarah 2:246–253, which demonstrates quite convincingly that the pericope should be read in the context of the Prophet’s need to motivate his community to take up arms after the hijrah.43 More substantially, Tilman Nagel’s magisterial Mohammed: Leben und Legende represents a deliberate attempt to return to the sources for the life of the Prophet and, after subjecting them to particular types of critical scrutiny, employ them to recover important aspects of the mission of Muḥammad as recounted in those sources as historically reliable.44 Nagel thus proposes to rehabilitate the type of historicizing interpretation of the Qurʾān pioneered by Theodor Nöldeke over a century and a half ago. His contribution to this issue makes his approach plainly apparent (albeit in miniature), reading the qurʾānic portrayals of Abraham, Noah, Moses and so forth as—in his own words—”a mirror reflecting the biography of Muhammad.”45

Strikingly, Nagel’s approach has in particular drawn the criticism of a number of scholars, though they themselves have sought to rehabilitate at least part of the early Islamic tradition and advocate for a more positivistic outlook, at least relative to the revisionist approach.46 Clearly not all scholars will be willing to embrace Nagel’s direct and unambivalent correlation of qurʾānic passages on the biblical prophets with episodes from Muḥammad’s life as known from the sīrah tradition. However, this biographical hermeneutic has the great virtue of allowing us to construe the underlying messages of qurʾānic recollections of the prophets in a meaningful way, permitting a coherent explanation of why these stories were recounted in the Qurʾān and what imperatives drove their reshaping in line with particular thematic patterns. That is, the particular narrative choices that inform the qiṣaṣ of the Qurʾān often seem so idiosyncratic, so personal, that reading them as messages of consolation to the individual conveying them to his fledgling community, or perhaps as warnings to his enemies, seems not only like a plausible, but in some sense the most logical and efficient, explanation for those choices. It is perhaps easier to believe that these prophetic narratives were crafted to conform to the experience of the historical prophet who related them than that the major details of the sīrah were fabricated to conform to the literary pattern that provides a template for the condensed narratives found in Sūrah 26 and elsewhere—though both scenarios remain feasible.

The Qurʾān represents a watershed moment in the larger intercommunal history of prophetic narratives. It canonizes a set of narrative presentations with complex and varying relationships to older biblical, Jewish, and Christian discourse and establishes a new foundation for interpretation of both specific details of these narratives and their overarching meaning. Pace Geiger, the base text underlying these prophetic narratives presupposed by the Qurʾān is—except in very few cases—neither the canonical Bible nor a closed canon of rabbinic literature, but rather an older and rather diffuse discourse, the broader biblical-Israelite tradition as it was constituted by a variety of scriptural and parascriptural formations in a number of different languages extant during the centuries leading up to the rise of Islam.

If the Qurʾān assimilated older prophetic traditions by boiling them down to their essence, to their mere “bones,” then the most characteristic aspect of the subsequent qiṣaṣ discourse is the tendency to restore flesh to those bones again by tapping into a fascinatingly heterogeneous body of material—by swathing them in what an older generation of scholars casually, but problematically, termed isrāʾīliyyāt.47

Sometimes Muslim authors and transmitters of qiṣaṣ restored features from Jewish and Christian precursors in elaborating a skeletal qurʾānic narrative back into a fully fleshed-out body. At other times, they constructed accounts that do not hearken back to pre-Islamic precursors at all, but rather represent something new and distinctive. In still other cases, authors of qiṣaṣ narratives did not engage with the Qurʾān directly but rather chose to sidestep the qurʾānic account, the details of which they may have seen—however paradoxically—as unnecessary to the story they wished to tell. All of these forms must be considered as important parts of the broader qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ tradition.48

‘Islamization’ and diversity: the case of Shi’i approaches to qiṣaṣ

In all their dazzling, kaleidoscopic variety, whether they build faithfully upon the qurʾānic presentation of a prophetic tale, are deeply engaged with (“influenced by”) older kitābī precursors, or take their narratives in wholly new directions, one thing unites all qiṣaṣ narratives. Regardless of their relationship to what came before, in the eyes of their Muslim authors and transmitters, qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ are meaningfully Islamic, deliberately crafted in a meaningfully Islamic way, intended to convey what to their authors were distinctively Islamic truths. These narratives are always formed by—and viewed by their audience through the lens of—values, belief structures, literary forms, and political, social, and religious concerns inspired at their foundation by the Qurʾān, but decisively shaped by later developments in the evolution of Muslim society and community.

Later qiṣaṣ works often stand in the same relationship to older received materials as the Qurʾān had—reshaping those materials and subordinating them to a new framework, through a process we might call ‘Islamization.’ But while we must acknowledge that an Islamic veneer is always placed over these stories as they are presented in new, distinctively Muslim, contexts, there is of course not one such mode of presentation, but rather a variety. To define qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ simply as the result of ‘Islamization,’ a reorientation of older material on the prophets in keeping with a set of identifiably Islamic values, traits, and cultural markers, presents a pitfall, in that we may be misled into implying that there is one monolithic set of such values, traits, and markers that all Muslims would recognize and see as authoritative.

This is surely fallacious. Rather, Islamization occurs through a dialogical process in which the particular significance of a story is determined in relationship to the specific concerns and predispositions of a particular audience—which are then shaped in turn, we might infer, by that story and the values it is tailored to communicate. We learn about an author’s conception of Islam by how they reframe and reshape stories, but that conception is of course not static or universal, because the priorities of every Muslim author and audience are different. We must thus keep in mind that Islamization is not a single, uniform process, but rather takes a variety of forms and aims at a variety of purposes; qiṣaṣ traditions thus represent and reflect the diverse Islams that give rise to them.49

This insight becomes particularly clear when we consider Shi’i versions and uses of qiṣaṣ narratives. Shi’i contributions to the shaping of distinctive Islamic conceptions of the biblical-Israelite prophets have historically been underappreciated. This is partially due simply to the overall neglect of Shi’ism as an integral part of the study of Islam in the West.50 But it is also due to the absence of a widely known major exemplar of the qiṣaṣ genre exhibiting a particularly Shi’i outlook.51 This is strange, however, since, as Rubin argued long ago in his classic discussion in “Prophets and Progenitors,” the impetus to collect and adapt stories of the pre-Islamic prophets first arose among the Shi’ah because of their interest in portraying those prophets essentially as precursors to their imāms.

It is also strange given that there are several lengthy and sophisticated works of Twelver and Isma’ili provenance that contain a significant amount of material on the prophets that have generally been excluded from discussions of qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ. For example, Rubin’s original article of 1979 relies extensively on material from Khargushī’s Sharaf al-muṣṭafā, an important eleventh century work on Muḥammad and the foreshadowing of his mission reflecting a distinctly Shi’i perspective. Despite the fact that Rubin and other scholars drew some attention to this work decades ago, it has seldom been studied, as it was long available only in a handful of manuscripts and in an edition produced as a Ph.D. thesis at the University of Exeter in 1986.52

An “imāmocentric” approach to prophetic precursors thus appears to have deeply impacted the qiṣaṣ tradition at an early date. Arguably, the emphasis on such themes by Shi’ah planted the seeds through which narratives about the prophets’ impeccability, or the transmission of a divine prophetic light across the generations, came to full fruition as widely disseminated motifs commonly linked to qiṣaṣ narratives in a variety of Muslim literatures.

The particular sectarian concerns of Shi’i authors were writ large in recastings or recontextualizations of prophetic narratives in numerous contexts, and not only during the tradition’s formative period. Gottfried Hagen’s contribution to this issue (“Salvation and Suffering in Ottoman Stories of the Prophets”) demonstrates vividly how Ottoman authors could present radically different understandings of prophetic history, focusing in particular on the pessimistic perspective of the Shi’i author Fuẓūlī. For Fuẓūlī, the lives of the prophets and imāms were characterized by suffering and struggle, the travails of the Alids and their faithful followers being foreshadowed by those of various prophetic precursors and their shīʿahs. For all, history was inevitably a vale of tears, and in Fuẓūlī’s view, according to Hagen, salvation for the Shi’ah represented at its core a full, existentially transformative realization and acceptance of this fact. This perspective differs sharply from that of the Qurʾān, which uses the stories of the prophets primarily as symbolic validation of the mission of the prophet through whom it was revealed, and in which the prophets certainly face challenges and disappointments (as Muḥammad himself did, as some might argue) but are ultimately vindicated before the evildoers who resist and reject them.

Another example is discussed in the contribution of George Warner (“Buddha or Yūdhāsaf? Images of the Hidden Imām in al-Ṣadūq’s Kamāl al-dīn”), which demonstrates a rather different type of Shi’i approach to prophetic history as outlined by the pioneering Twelver scholar Ibn Bābawayh, commonly known as al-Shaykh al-Ṣadūq. In Ṣadūq’s work, qiṣaṣ accounts are deliberately framed so as to vindicate the emergent Imami doctrine of occultation. The text is significant not only for the explicit way in which prophetic narratives are shaped for specific dogmatic purposes, but also for the variety of complementary material Ṣadūq draws into his work. As Warner argues, the material on the Hidden Imām in the text interacts with and relates to that on the biblical/qurʾānic prophets in complex and intriguing ways, as well as being implicitly validated (on a narrative if not doctrinal level) through its parallels with legendary material Ṣadūq includes in his work, most conspicuously a well-known Islamicized cycle of narratives about the Buddha.

Shi’i approaches to qiṣaṣ tend to be transparently sectarian, and so present us with prophetic accounts in which the purpose and effects of narrating qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ—of a particular literary use of the biblical-qurʾānic prophets—are explicit, or at least conspicuous, because of their overtly political nature. In light of their evident value to the field in making the means and ends of Islamization abundantly clear, it is striking that Shi’i materials have long been understudied in the scholarly literature on qiṣaṣ, for example the numerous works of Isma’ili taʿwīl that often invoke prophetic accounts as foreshadowing the lives of the imāms.53

However, it is important to recognize that all recastings and reinterpretations of qiṣaṣ, from the Qurʾān down to today, are in fact ‘sectarian’ on some level. Not only is it the case that all articulations of Islam are legitimate prima facie regardless of their acceptability to representatives of other articulations, and that no single form can be privileged as normative or ‘original’ above others; rather, more to the point, specific perspectives on questions of typically ‘sectarian’ concern such as authority, identity, and communal belonging are always present, whether they are writ large or rather tend to be explored only implicitly. Thus, any Muslim community’s reshaping of older narratives and repurposing of prophetic figures as symbols can be thought of as ‘Islamization,’ but this can only occur through aligning them with that community’s ideas and attitudes about those questions of sectarian concern, which almost inevitably differ from those of other Muslim communities in important ways.

Thus, Sunni qiṣaṣ is no less sectarian than Shi’i qiṣaṣ in this regard, though the politico-communal implications of the former are perhaps harder to detect because we tend to naturalize the Sunni perspective as universal, essentially or typically ‘Islamic.’ The exegeses of qurʾānic narratives about the prophets by spokesmen of the Shi’ah or other ‘sectarian’ formations like the Nation of Islam are perhaps more explicitly presentist than that of other groups, or more closely attuned to specifically minoritarian issues, but all Muslim engagement with these pre-Islamic figures and the implications of their missions to Israel or other communities is on some level informed by the current concerns of the interpreter and their time. This is simply an extension of the contemporizing impulse already latent in the qurʾānic presentation of these figures.

The development of qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ is thus most accurately described as the history of complex processes of Islamization of prophetic narratives, usually drawing on a variety of predecessors, but with the caveat that Islamization can mean rather different things depending upon the context in which portrayals are framed, even upon the particular outlook and idiosyncrasies of the author in question.

Intertwined genres and the future of the field

Returning to the question of genre, due to the rootedness of qiṣaṣ in the Qurʾān, much material was obviously generated in the course of scriptural exegesis. The development of said material often followed complex and winding paths. Thus, as Carol Bakhos’ contribution to this issue (“A Migrating Motif: Abraham and his Adversaries in Jubilees and al-Kisāʾī”) shows, a significant transformation, even transference, of tropes and themes between accounts of episodes in the lives of the prophets occurred in the course of the tradition’s evolution. As part of an ongoing circulation of motifs first attested in Second Temple literature, these motifs appear in both Jewish and Islamic sources over a thousand years later, adapted to new cultural settings and sometimes transmuted so that only distant, but still discernible, echoes of the originals remain. This, Bakhos argues, is the case with the portrayal of an arch-enemy of Abraham who appears in the guise of the diabolical antagonist Mastemah in Jubilees, resonant a millennium later in the characterization of Nimrod in the qiṣaṣ of Kisāʾī.

Notably, cross-fertilization between genres appears to have continued well after the coalescence of what became the classic literary forms dominant in Islamic culture. Exegetical, historiographic, ḥadīth-based, and belle-lettristic qiṣaṣ material did not remain confined to those genres but flowed freely between them. Helen Blatherwick’s contribution to this issue (“Solomon Legends in Sīrat Sayf ibn Dhī Yazan”) focuses on the prophetic legends in the popular epic Sīrat Sayf dhī Yazan, replete with allusions to classic themes and scenarios from qiṣaṣ accounts of the prophet-king Solomon; in the articulation of a new literary-legendary account of the exploits of this Yemenite king, this popular sīrah exploits the stock of material on Solomon that its audience likely took for granted as common knowledge to provide an evocative subtext to its own narrative.

As mentioned previously, communal boundaries were sometimes as porous as genre boundaries. Shari Lowin’s discussion of what appear to be complementary allusions to a specific element from the story of Joseph in two poems from al-Andalus, one Muslim and one Jewish (“The Cloak of Joseph: A Qiṣaṣ al-Anbiyāʾ Image in an Arabic and a Hebrew Poem of Desire”), indicates not only that qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ could provide subtle, rich layers of meaning in a variety of literary forms, but also that these layers of meaning were the common property of, and accessible to, authors in the Islamicate milieu regardless of their specific religious identity or communal affiliation.

The Blatherwick and Lowin articles remind us that just as an overemphasis on qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ as a specific genre rather than a broader discourse has perhaps limited the field, so too has the exaggerated interest in qiṣaṣ narratives as articulated in the exegesis of the Qurʾān to the detriment of explorations of prophetic themes and motifs as elaborated in other literary corpora. One of the most open frontiers of qiṣaṣ studies is thus surely the examination of the pre-Islamic prophets and their manifold significations in philosophy and theology, adab (especially post-classical literary arts in Persian and Turkish), the visual arts, and other realms of Muslim meaning-making.54

There is some precedent for a broader, more encompassing approach. The privileging of the exegetical over other areas colors much significant early Orientalist interest in qiṣaṣ material as primarily manifest in Qurʾān and tafsīr, from classic works in the field—for example Marracci, Geiger, Weil, and Speyer—all the way up to the present day—e.g., Wheeler and Reynolds.55 But other trajectories have at times been manifest in scholarship, however. For example, in d’Herbelot’s once-influential but now generally neglected Bibliothèque Orientale, the presentations of biblical figures in Islamic guise are undoubtedly informed by tafsīr materials (e.g., the commentary of Ḥusayn Wāʿiẓ Kāshifī, perhaps d’Herbelot’s main touchstone for the Qurʾān and its interpretation), but they are also at times inflected by the author’s familiarity with Persian literature and seemingly more ‘folkloric’ sources.56

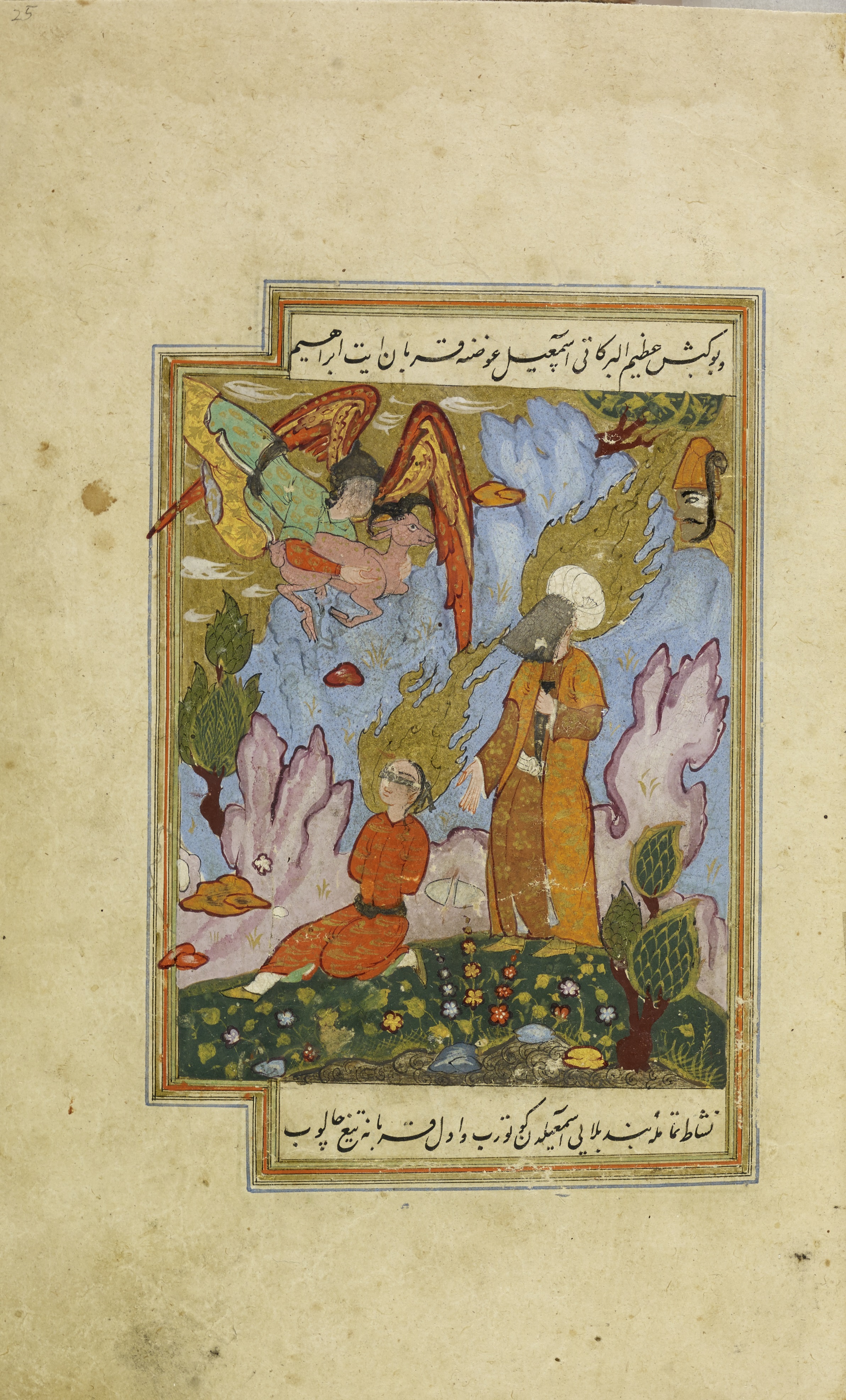

As noted above, the gradual but steady progress in the appearance of works in new editions, mainly produced in the Islamic world and of varying quality, has as yet had only a modest impact in stimulating the growth of new approaches and focal points in research on qiṣaṣ. Clearly much remains to be done in realizing the potential gains from interdisciplinary approaches to the subject. For example, a number of publications in art history over the last twenty-five years have demonstrated that the pre-Islamic prophets were extensively depicted in the pictorial arts of Islam over a very long period of time, but this material has only just begun to be catalogued, let alone marshaled in the study of the larger qiṣaṣ tradition.57 These publications present valuable visual resources awaiting broader analysis and integration with literary evidence. An interdisciplinary and integrative approach that made use of both visual and literary materials would be particularly beneficial because the ideologically charged nature of visual depictions tends to be rather conspicuous, especially given their commissioning by and production for royal patrons. Visual materials pertaining to the pre-Islamic prophets thus provide us with vivid examples of a specific type of Islamization of biblical figures; the function of these figures as symbolic touchstones for religio-political legitimacy is usually rather overt.58

This journal issue aims to make a small contribution to advancing the field by showcasing new research in qiṣaṣ studies. The articles featured here demonstrate that current scholarship on qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ adopts a variety of disciplinary perspectives, reflects diverse concerns, and approaches the broader qiṣaṣ tradition in all its breadth and nuance, particularly focusing on the overlooked aspects of that tradition. Many of these articles discuss material from the post-classical period, especially historically neglected material from Shi’i literature, popular epic, and modern literary settings. As the contributions of Ayşe Polat (“The Human Jesus: A Debate in the Ottoman Press”) and Herbert Berg (“Elijah Muhammad’s Prophets: From the White Adam to the Black Jesuses”) show, significant reflection on and uses of qiṣaṣ in the twentieth century may occur in surprising contexts, expressing the unique concerns of their eras and originating communities, and may bear little or no resemblance to the classical articulations of their subject. In fact, in both of these cases, in the late Ottoman milieu of the early twentieth century and the African American milieu some decades later, not only do the authors elaborating new forms of qiṣaṣ largely or wholly neglect classical sources pertinent to their themes, but the Qurʾān itself may be largely or entirely absent from the debate. And yet, the result of reflection on Abraham, Moses, and Jesus by Turkish modernists or the main spokesman of the American Nation of Islam is meaning-making through the prophets that is characteristically, vibrantly, indisputably Islamic, and so quintessentially part of the qiṣaṣ tradition.

The future growth of the field may lead to such a degree of diffusion of approach and subject matter as to challenge the whole presupposition that there even is a field of qiṣaṣ studies, although it is clear what all the articles in this issue at least have in common. All prioritize the question of what is distinctively Islamic in various Muslim reinterpretations of qiṣaṣ narratives over that of sources or influences; most of the articles here simply do not address the question of origins or precursors at all. In this sense, they epitomize the idea that qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ is not really about ‘biblical prophets in Islam’ or even ‘biblical-qurʾānic prophets’ but rather simply Islamic prophets—with the meaning of “Islamic” varying enormously from author to author and context to context.

In the end, this brings us back full circle to the work of Nagel we commemorate and celebrate here, in that his pioneering work on qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ as a genre originally aimed (and has continued to aim) at discerning what was or has been distinctively Islamic about the Islamic stories of the prophets. This journal issue hopefully makes clear that the question of how Muslims have articulated specifically Islamic expressions and forms of meaning through the stories of the prophets is of perennial relevance, from the Qurʾān down to the modern era, and that qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, as genre and discourse, is of significant value for examining conceptions of Islam itself in a vast diversity of Muslim communities and traditions.

About the authors

Michael Pregill (Ph.D., Columbia University, 2007) is Interlocutor in the Institute for the Study of Muslim Societies and Civilizations at Boston University. His primary area of expertise is early Islam, with a specific focus on the Qurʾān and its interpretive tradition (tafsīr). Much of his research concerns the reception and interpretation of biblical, Jewish, and Christian themes and motifs in tafsīr and other branches of classical Islamic literature; critical approaches to Islamic origins; and the perception and representation of Jews and Christians in Islamic culture.

Marianna Klar (D.Phil. University of Oxford, 2002) is Research Associate in the Centre of Islamic Studies, SOAS. Her research focuses on tales of the prophets within the Islamic tradition, on issues of genre pertaining to medieval texts, and on the Qur’an’s narratives and its literary structure. Her published works include Interpreting al-Thaʿlabī’s Tales of the Prophets: Temptation, Responsibility and Loss (London: Routledge, 2009) and, more recently, “Between History and Tafsīr: Notes on al-Ṭabarī’s Methodological Strategies,” Journal of Qur’anic Studies 18 (2016): 89–129 and “Re-examining Textual Boundaries: Towards a Form-Critical Sūrat al-Kahf, in Walid A. Saleh and Majid Daneshgar (eds.), Islamic Studies Today: Essays in Honor of Andrew Rippin (Leiden: Brill, 2016), 215–238.

Roberto Tottoli (Ph.D., Naples L’Orientale, 1996) is Professor of Islamic Studies at the University of Naples L’Orientale. He has published studies on the biblical tradition in the Qurʾān and Islam (Biblical Prophets in the Qur’an and Muslim Literature [Richmond: Curzon, 2002]; The Stories of the Prophets by Ibn Muṭarrif al-Ṭarafī [Berlin: Klaus Schwartz Verlag, 2003]) and medieval Islamic literature. His most recent publication, coauthored with Reinhold F. Glei, is Ludovico Marracci at Work: The Evolution of His Latin Translation of the Qurʾān in the Light of His Newly Discovered Manuscripts (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2016).

Notes

1 Tilman Nagel, “Die Qiṣaṣ Al-Anbiyāʾ: Ein Beitrag zur Arabischen Literaturgeschichte” (Ph.D. diss., Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, 1967).

2 For a survey of recent trends in the field as regards the discovery and publication of primary sources, see Roberto Tottoli, “New Sources and Recent Editions of Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ Works and Literature,” in Raif Georges Khoury, Juan Pedro Monferrer-Sala, and María Jesús Viguera Molins (eds.), Legendaria medievalia: En honor de Conceptión Castillo Castillo (Cordoba: Ediciones El Almendro, 2011), 525–539.

3 Cf. e.g., Ján Pauliny, “Some Remarks on the Qiṣaṣ al-Anbiyāʾ Works in Arabic Literature,” trans. Michael Bonner, in Andrew Rippin (ed.), The Qur’an: Formative Interpretation (Formation of the Classical Islamic World 25; Aldershot: Ashgate Variorum, 1999), 313–326; W. M. Thackston (ed. and trans.), The Tales of the Prophets of al-Kisa’i (Library of Classical Arabic Literature 2; Boston: Twayne, 1978), xi–xxvi.

4 Mark Lidzbarski, De Propheticis, quae dicuntur, legendis arabicis (Leipzig, 1893).

5 Muḥammad b. ʿAbdallāh al-Kisāʾī, Vita Prophetarum auctore Muhammad ben Abdallah al-Kisa’i, ed. Isaac Eisenberg (Leiden: Brill, 1923).

6 D. Sidersky, Les Origines des Légendes Musulmanes dans le Coran et dans les vies des prophètes (Paris: Librarie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, 1933).

7 Josef Horovitz, Koranische Untersuchungen (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1926); Heinrich Speyer, Die biblischen Erzählungen im Koran (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1961); Abraham Geiger, “Was hat Mohammed aus dem Judenthume aufgenommen?” (Bonn, 1833).

8 These terms appear to have been largely interchangeable in the early tradition, as evidenced by the fact that the titles of works in the genre were mutable; e.g., Kisāʾī’s text apparently circulated as Kitab Badʾ al-khalq as well as Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, and Mubtadaʾ was still known as a title for works or sections of works dealing with the stories of the prophets.

9 Tilman Nagel, “How to Achieve an Islamic Interpretation of the Qiṣaṣ al-Anbiyāʾ: On the Prophetic Stories of the Qurʾān.”

10 For an indispensable overview of the tradition, see Roberto Tottoli, Biblical Prophets in the Qurʾān and Muslim Literature (Richmond: Curzon, 2002). A representative selection of material organized sequentially according to the chronological order of the prophets (thus mimicking an actual qiṣaṣ work) is Brannon M. Wheeler, Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis (London: Continuum, 2002).

11 For example, it is commonly observed that Moses is the figure most frequently mentioned in the Qurʾān, referred to over a hundred times, with hundreds of verses dedicated to recounting his story and various episodes pertaining to the Exodus and the revelation of the Torah. Narratives pertaining to the pre-Islamic prophets comprise at least a quarter of the Qurʾān overall, possibly more.

12 See Tottoli, “New Sources,” 526–528 on the example of the new Arabic editions of Kisāʾī.

13 Cornelia Schöck, Adam im Islam: Ein Beitrag zur Ideengeschichte der Sunna (Islamkundliche Untersuchungen 168; Berlin: Klaus Schwarz Verlag, 1993); Waltraud Bork-Qaysieh, Die Geschichte von Kain und Abel (Hābil wa-Qābil) in der sunnitisch-islamischen Überlieferung: Untersuchungen von Beispielen aus verschiedenen Literaturwerken under Berücksichtigung ihres Einflusses auf den Volksglauben (Islamkundliche Untersuchungen 169; Berlin: Klaus Schwarz Verlag, 1993); Peter J. Awn, Satan’s Tragedy and Redemption: Iblīs in Sufi Psychology (Studies in the History of Religion [Supplements to Numen] 44; Leiden: Brill, 1993); Whitney S. Bodman, The Poetics of Iblīs: Narrative Theology in the Qur’an (Harvard Theological Studies 62; Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011); Reuven Firestone, Journeys in Holy Lands: The Evolution of the Abraham-Ishmael Legends in Islamic Exegesis (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990); Shari L. Lowin, The Making of a Forefather: Abraham in Islamic and Jewish Exegetical Narratives (Islamic History and Civilization Studies and Texts 65; Leiden: Brill, 2006); Brannon M. Wheeler, Moses in the Quran and Islamic Exegesis (London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2002); Khaleel Mohammed, David in the Muslim Tradition: The Bathsheba Affair (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2015); Jacob Lassner, Demonizing the Queen of Sheba: Boundaries of Gender and Culture in Postbiblical Judaism and Medieval Islam (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993); Jean-Louis Déclais, David raconté par les musulmans (Paris: Cerf, 1999); idem, Un récit musulman sur Isaïe (Paris: Verf, 2001); idem, Les premiers musulmans face à la tradition biblique: trois récits sur Job (Paris: Harmattan, 1996); Todd Lawson, The Crucifixion and the Qur’an: A Study in the History of Muslim Thought (Oxford: OneWorld, 2009); Tarif Khalidi, The Islamic Jesus: Sayings and Stories in Islamic Literature (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003).

14 M. O. Klar, Interpreting al-Thaʿlabī’s Tales of the Prophets: Temptation, Responsibility and Loss (London: Routledge, 2009). We might also mention the work of the Israeli scholars Tamari and Koch in editing and translating the ʿAjāʾib al-malakūt attributed to Kisāʾī, a work collecting popular traditions on cosmology and eschatology and so related to qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ. It should be noted, however, that the editors’ highly idiosyncratic conjectures about the author and the transmission of the work (viz., that Kisāʾī was a convert from Judaism or a “Muslim-Jew” following a syncretic faith whose links to Judaism were suppressed in the subsequent redaction of his work) is far outside the consensus and would not be accepted by scholars in the mainstream. See the extensive (and highly opaque) comments in the introduction of Kisāʾī, Kitāb ʿAjāʾib al-malakūt, ed. and trans. Shmuel Tamari and Yoel Koch (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2005).

15 For English and German translations of Thaʿlabī, see: ʿArāʾis al-majālis fī qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, or, ‘Lives of the Prophets’ as recounted by Abū Isḥāq Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad ibn Ibrāhīm al-Thaʿlabī, trans. William M. Brinner (Studies in Arabic Literature 24; Brill, 2002) and Islamische Erzählungen von Propheten und Gottesmännern: Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ oder ʿArāʾis al-mağālis von Abū Isḥāq Aḥmad b. Muḥammad b. Ibrāhīm aṯ-Ṯaʿlabī, trans. H. Busse (Diskurse der Arabistik 9; Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2006). Thackston’s older translation of Kisāʾī into English, as well as Ján Pauliny’s partial translation into Czech (Abú al-Hasan al-Kisái, Kniha o počiatku a konci a rozprávania o prorokoch, Islámske mýty a legendy [Bratislava: Tatran, 1980]) are now complemented by that of Aviva Schussman into Hebrew: see Sipurei ha-nevi’im me’et Muḥammad b. ʿAbd Allah al-Kisa’i (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University Press, 2013).

16 Most of the relevant qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ material from Ṭabarī’s chronicle is available in English in the first three volumes of the Bibliotheca Persica translation of the work. See The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume I: General Introduction and From the Creation to the Flood, trans. Franz Rosenthal (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1989); The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume II: Prophets and Patriarchs, trans. William Brinner (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1987); The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume III: The Children of Israel, trans. William Brinner (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1991). Additionally, although only the first volume of the planned translation of Ṭabarī’s tafsīr into English has ever appeared, that volume spans much of Sūrat al-Baqarah and thus contains significant material pertaining to qiṣaṣ. See The Commentary on the Qurʾān by Abū Jaʿfar Muḥammad b. Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, trans. Alan Cooper (London: Oxford University Press, 1987).

17 The aforementioned work of Wheeler, Prophets in the Quran, exemplifies the underlying tensions that inform scholarly approaches to this material. Despite its explicit presentation as primarily oriented towards exegetical material, Wheeler draws on an impressive breadth of sources for the traditions cited therein, at least judging from the list of works utilized in the anthology that he provides at the end of the book. However, frustratingly, the individual traditions Wheeler cites are sourced, but he arbitrarily assigns said traditions either to authors of compilations or to major authorities to whom traditions are attributed, and in the case of the latter, no indication of the actual literary source is given. The exegetical-commentary structure thus dominates the work, and the reader is given little indication of the variety of literary contexts and frameworks in which this material was actually deployed.

18 See Johann Pedersen, “The Criticism of the Islamic Preacher,” Die Welt des Islams 2 (1953): 215–231; Schwartz’s introductory comments in Abū’l-Faraj ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Ibn al-Jawzī, Ibn al-Jawzī’s Kitāb quṣṣāṣ wa’l-mudhakkirīn, trans. Merlin Swartz (Beirut: Dar el-Machreq, 1971); and Lyall Armstrong, The Quṣṣāṣ of Early Islam (Leiden: Brill, 2017). There has been relatively little attempt to investigate the milieu in which this material was first generated more closely or to rethink the paradigm through which we conceptualize its origins. On the former point, see Raif Georges Khoury, “Story, Wisdom, and Spirituality: Yemen as the Hub between the Persian, Arabic and Biblical Traditions,” in Johann P. Arnason, Armando Salvatore, and Georg Stauth (eds.), Islam in Process: Historical and Civilizational Perspectives (Yearbook of the Sociology of Islam 7; Bielefeld: Transcript, 2006), 190–219. On the latter, see Michael Pregill, “Isrāʾīliyyāt, Myth, and Pseudepigraphy: Wahb b. Munabbih and the Early Islamic Versions of the Fall of Adam and Eve,” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 34 (2008): 215–284.

19 As has often been remarked, Thaʿlabī’s qiṣaṣ begins with an elaboration of the various ḥikmahs (“wisdoms”) that explain why Muslims should seek to learn and reflect on qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ; the second ḥikmah is that the earlier prophets provide a paradigm for understanding Muḥammad himself and the significance of his mission. See Thaʿlabī, ʿArāʾis al-majālis, trans. Brinner, 4; Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ al-musammā ʿArāʾis al-majālis (Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyyah, 1985), 2–3.

20 Here we might note the striking phenomenon of the emergence of an actual genre of books entitled qiṣaṣ al-Qurʾān in the twentieth century, modern works of a Salafi tendency that attempt to discard the traditional accretions (especially the so-called isrāʾīliyyāt) in the literature on the prophets so as to present the supposedly most authoritative and authentically Islamic portrayals of their missions and exploits. This is complemented by modern works that, while retaining the title qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, systematically and explicitly subject the traditional material on the topic to significant criticism, again in pursuit of obtaining pure and reliable accounts rooted in the Qurʾān; foremost among these is ʿAbd al-Wahhāb al-Najjār, Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ (Cairo: Maṭbaʿat al-ʿUlūm, 1932). On Najjār’s work in the context of Egyptian intellectuals’ attempt to reconfigure Islamic tradition for a modern, literate audience, see Israel Gershoni, “Reconstructing Tradition: Islam, Modernity, and National Identity in the Egyptian Intellectual Discourse, 1930–1952,” in Moshe Zuckermann (ed.), Ethnizität, Moderne und Enttraditionalisierung (Tel Aviver Jahrbuch für deutsche Geschichte 30; Tel Aviv: Wallstein Verlag, 2002), 156–211. Cf. Tottoli, Biblical Prophets, 175–188 on modernist approaches to qiṣaṣ.

21 On the impact of such qurʾānic conceptions as covenant, sin and punishment, and messianic redemption on Islamic historiography, see R. Stephen Humphreys, “Qur’anic Myth and Narrative Structure in Early Islamic Historiography,” in F. M. Clover and R. S. Humphreys (eds.), Tradition and Innovation in Late Antiquity (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989), 271–292 and Tayeb El-Hibri, Parable and Politics in Early Islamic History: The Rashidun Caliphs (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010).

22 As noted by Tottoli (“New Sources,” 526–528) two new editions of Kisāʾī’s work—the first printed editions from the Arab world—have appeared, one in 1998 and one in 2008. Neither of these seems as yet to have had much of an impact or supplanted scholars’ reliance on the much older and often deficient edition of Eisenberg.

23 Gordon Darnell Newby, The Making of the Last Prophet: A Reconstruction of the Earliest Biography of Muḥammad (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1989). See Newby’s comments in the introduction to the work (1–25), in which his assumptions about the original shape, sequence, and purpose of the work are laid out. See also the review of Lawrence I. Conrad, “Recovering Lost Texts: Some Methodological Issues,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 113 (1993): 258–263, calling Newby’s methodology into question to such a severe degree that he expresses doubt as to whether Newby’s result could possibly resemble Ibn Isḥāq’s original Kitāb al-Mubtadaʾ—”a perhaps vexed concept in any case” (250)—at all.

24 The Bodleian manuscript of Isḥāq b. Bishr is integral to two seminal articles by Kister on qiṣaṣ themes: M. J. Kister, “Legends in tafsir and hadith Literature: The Creation of Ādam and Related Stories,” in Andrew Rippin (ed.), Approaches to the History of the Interpretation of the Qur’an (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), 82–114; idem, “Ādam: A Study of Some Legends in Tafsīr and Ḥadīt Literature,” Israel Oriental Studies 13 (1993): 113–174.

25 ʿUmārah b. Wathīmah al-Fārisī, Les légendes prophétiques dans l’Islam depuis le Ier jusqu’au IIIe siècle de l’Hégire. Kitāb bad’ al-ḫalq wa-qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ. Avec édition critique du texte, ed. R. G. Khoury (Codices Arabici Antiqui 3; Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1978); Ibn Muṭarrif al-Ṭarafī, The Stories of the Prophets by Ibn Muṭarrif al-Ṭarafī, ed. Roberto Tottoli (Islamkundliche Untersuchungen Band 253; Berlin: Klaus Schwarz Verlag, 2003).

26 That is, a rarely attested form of written Turkish that marked the transition from Karakhanid to Chagataic as one of the dominant forms of Turkish in the region in the early Mongol period. See al-Rabghūzī, The Stories of the Prophets. Qiṣaṣ al-anbiyā’: An Eastern Turkish Version, ed. by H. E. Boeschoten and J. O’Kane (2nd ed.; 2 vols.; Leiden: Brill, 2015).

27 Saleh contends that Thaʿlabī’s marginalization was due to the perception that he was a crypto-Shi’i, though the rationale that he was an unreliable transmitter of ḥadīth is often cited in works criticizing him. See Walid Saleh, The Formation of the Classical Tafsīr Tradition: The Qurʾān Commentary of al-Thaʿlabī (d. 427/1035) (Leiden: Brill, 2004), e.g., 216–221 on Ibn Taymiyyah’s engineering of Thaʿlabī’s rejection from the orthodox Sunni fold, leading to the tenuous position he occupies today, at least among Salafi scholars of tafsīr and tradition.

28 On the isrāʾīliyyāt problem, see below. The oldest printed editions of Ibn Kathīr’s qiṣaṣ seem to go back to the 1960s, but little is known of the circumstances of its production. A recent presentation of Ibn Kathīr’s material on the prophets in English appears to be a revised version of the qiṣaṣ in circulation in Arabic, produced by going back to the Bidāyah and re-extracting the material so as to emphasize the most authentic ḥadīth and exclude even more isrāʾīliyyāt: Ibn Kathīr, Life and Times of the Messengers, Taken from Al-Bidayah wan-Nihayah (Riyadh: Darussalam Publishers, 1428/2007).

29 The term “discourse” is often bandied about without much critical reflection upon its significance or implications. Here I invoke it to signify a mode of communication, a way of talking about things through a well-established set of symbols that reflects, evokes, and reinforces specific constructions of authority. This is essentially the conception of discourse established in Lincoln’s robust investigations of the symbolic language of religious and quasi-religious ritual; see, e.g., Bruce Lincoln, Discourse and the Construction of Society (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989).

30 The Byzantine Lives, seldom if ever considered as a forerunner to qiṣaṣ al-anbiyāʾ, is available in a still-serviceable translation by Torrey: The Lives of the Prophets: Greek Text and Translation, trans. Charles Cutler Torrey (Journal of Biblical Literature Monograph Series 1; Philadelphia: Society of Biblical Literature, 1946). Torrey’s approach to the text reflects the conventional belief that it is by and large a Jewish work of first-century Palestine, but the more recent evaluation of Satran is that the text as currently extant must be considered a late antique Christian document. See David Satran, Biblical Prophets in Byzantine Palestine: Reassessing the Lives of the Prophets (Leiden: Brill, 1994).

31 Note that some traditionists roughly contemporary with Ibn Isḥāq do seem to have had more purely antiquarian motivations for collecting material pertaining to the prophets, typically in conjunction with a specific topos such as wisdom traditions or a particular geographical arena such as the Yemen. See, e.g., the (putatively fictitious or pseudepigraphic) Akhbār Yaman of ʿAbīd b. Sharyah: Elise W. Crosby, The History, Poetry, and Genealogy of the Yemen: The Akhbar of Abid b. Sharya Al-Jurhumi (Gorgias Dissertations 24, Arabic and Islamic Studies 1; Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias, 2007).

32 The term mubtadaʾ may be translated “prologue,” “foreshadowing,” or “precursor” (Newby even suggests “Genesis,”) which the mabʿath (“prophetic commission” or “sending-forth”) and maghāzī (“raids” or “campaigns”) follow.

33 See Uri Rubin, “Prophets and Progenitors in the Early Shīʿa Tradition,” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 1 (1979): 41–65.

34 John Wansbrough, The Sectarian Milieu: Content and Composition of Islamic Salvation History, foreword, translations, and expanded notes by Gerald Hawting (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2006 [1978]). See also Fred Donner, Narratives of Islamic Origins: The Beginnings of Islamic Historical Writing (Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam 14; Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1998), 149–159 on the emergence of prophetic themes as a specific form of historical reflection in the emergent Muslim community.

35 This conception of the supersessionist ideology that informs the mubtadaʾ is most clearly articulated in Gordon D. Newby, “Text and Territory: Jewish-Muslim Relations 632–750 CE,” in Benjamin H. Hary, John L. Hayes, and Fred Astren (eds.), Judaism and Islam: Boundaries, Communication and Interaction: Essays in Honor of William M. Brinner (Leiden: Brill, 2000), 83–95, in which he draws attention to the parallels between Ibn Isḥāq’s sīrah and the post-Islamic midrashic work Pirqei de-Rabbi Eliezer as rival expressions of prophetic history, the latter reflecting Jewish resistance to appropriation. On the continuity of Christian habitus, especially polemical and supersessionist models of history, with the Qurʾān and early Islam, see David Nirenberg, Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition (New York: W. W. Norton, 2013), Ch. 4.

36 Camilla Adang, Muslim Writers on Judaism and the Hebrew Bible: From Ibn Rabban to Ibn Hazm (Islamic Philosophy, Theology, and Science 22; Leiden: Brill, 1996).

37 Ibn Isḥāq’s supersessionist vision was probably foreshadowed by the work of previous generations of exegetes and traditionists, who at least implicitly had a similar conception of the material they collected on the theme of Muḥammad’s precursors, but Ibn Isḥāq’s extended narration of prophetic history, drawing direct parallels between the Israelite prophets and Muḥammad, likely represents the first mature literary statement on this subject. Cf. Uri Rubin, The Eye of the Beholder: The Life of Muḥammad as Viewed by the Early Muslims, A Textual Analysis (Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam 5; Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1995) on elements in the biography of Muḥammad constructed to validate his mission by presenting it as a parallel to or fulfillment of biblical prophecy.