PDF

Download

Citations

Click and drag then release to select a passage to cite.

Annotations

How to submit annotations to Mizan Journal articles:

your work is published.

Search within

On Michigan Manuscript Isl. Ms. 386

Fuẓūlī’s Garden of the Felicitous

Image

Audio

Video

Chart or Graph

On Michigan Manuscript Isl. Ms. 386

Fuẓūlī’s Garden of the Felicitous

About Michigan Isl. Ms. 386

This issue of Mizan dedicated to the Islamic tales of the prophets features a number of images from a manuscript preserved in the University of Michigan Library under the shelfmark Isl. Ms. 386.

The compact volume of beige Persianate paper carries a late sixteenth-century manuscript witness of Hadikatü’s-süada (Garden of the Felicitous), a maqtal or martyrology commemorating the suffering of the prophets, particularly the tragedy at Karbalāʾ, by the illustrious Turkish poet Fuẓūlī (d. 963/1556).1

The richly ornamented volume has been trimmed and resewn, and is presently bound in a two-piece cover of painted lacquerwork featuring a typical book cover composition of central mandorla and pendants in gold vegetal motifs. This cherished cover is likely not original to the present text block, but rather was produced for another manuscript, specially preserved and reused on this manuscript.

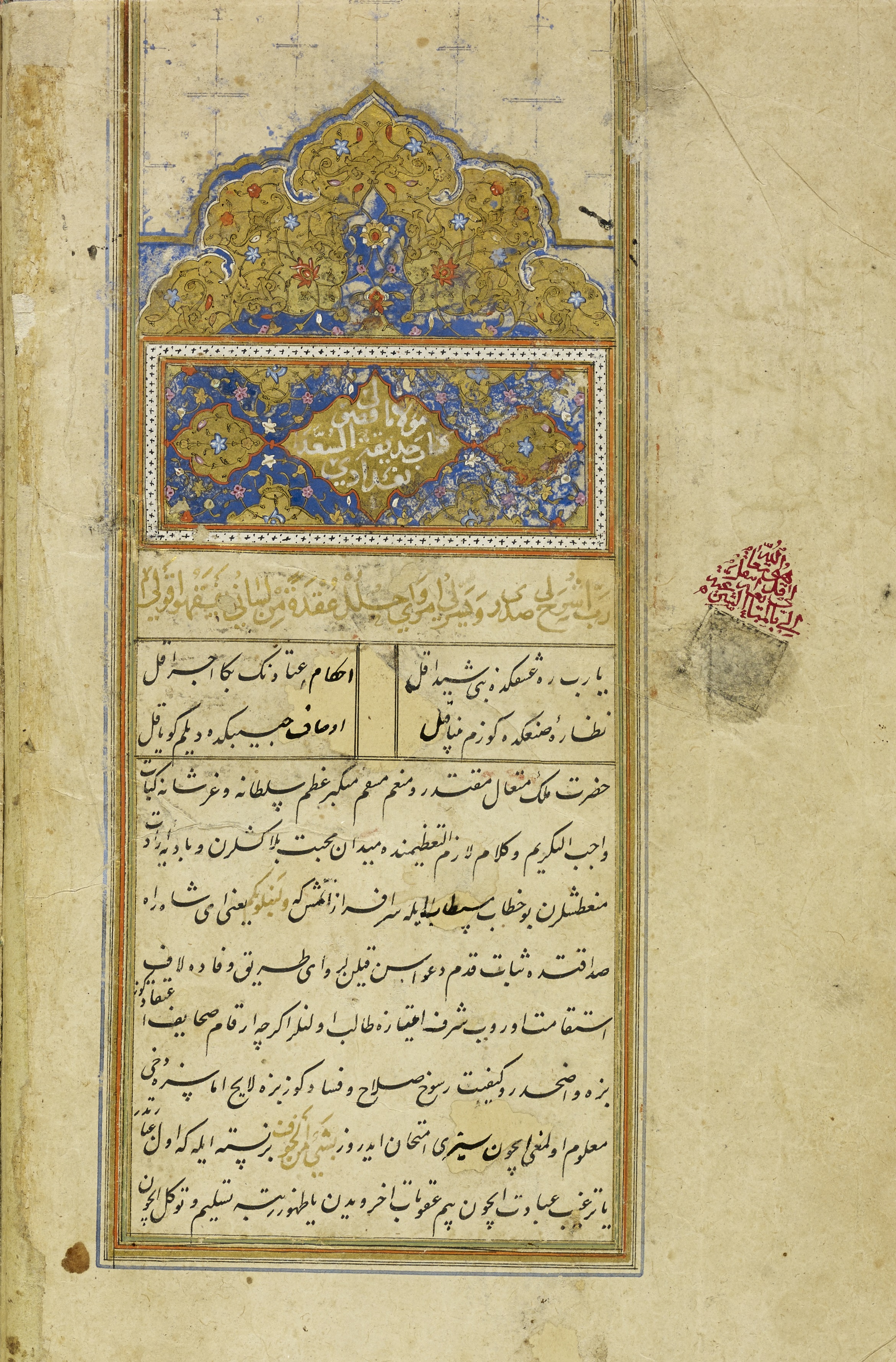

An illuminated headpiece sets off the opening of the text, and features a scalloped golden dome filled with floral-vegetal designs surmounting a cartouche carrying the title and author of the work in white riqāʿ script (see Gallery Image A).

The text is set in a spacious column of fifteen lines per page—occasionally divided into two columns to set off lines of verse—and written in a refined Ottoman talik (i.e. nastaʿlīq) that is characteristically serifless with a gentle effect of words descending to the baseline, elongated horizontal strokes, and pointing in distinct dots. Headings and keywords are rubricated or chrysographed and a polychrome frame surrounds the written area.

As with numerous other copies of the work, the manuscript is generously illustrated with thirteen paintings depicting episodes from the text, featuring the prophets and Alid imāms who are the work’s protagonists:

Abraham catapulted into the fire (p.17)

Abraham about to sacrifice his son (p.25)

Joseph’s brothers and the wolf before Jacob (p.48)

Pursuers sawing the tree in which Zechariah is hiding (p.75)

Ḥamzah beats Abū Jahl with his bow (p.92)

The Prophet Muḥammad in battle, likely at Uḥud (p.95)

The Prophet Muḥammad emerging from the cave (p.100)

ʿAlī in battle (p.103)

Death of the Prophet Muḥammad (p.137)

Assassination of ʿAlī (p.244)

Muslim b. ʿAqīl comes out against his attackers at Ṭawʿah’s house (p.357)

Duel of Qāsim b. Ḥasan and Azraq at Karbalāʾ (p.481)

Zayn al-ʿĀbidīn preaching in the mosque in exculpation of al-Ḥusayn (p.571)

As is typical, each prophet or imām is visually signified by a luminous halo, the flames of which often pierce the boundary of the written area and spill into the margins along with other elements of the composition. A later viewer with more reserved sensibilities toward the depiction of holy persons has added somewhat crude veils over the faces of the prophets.

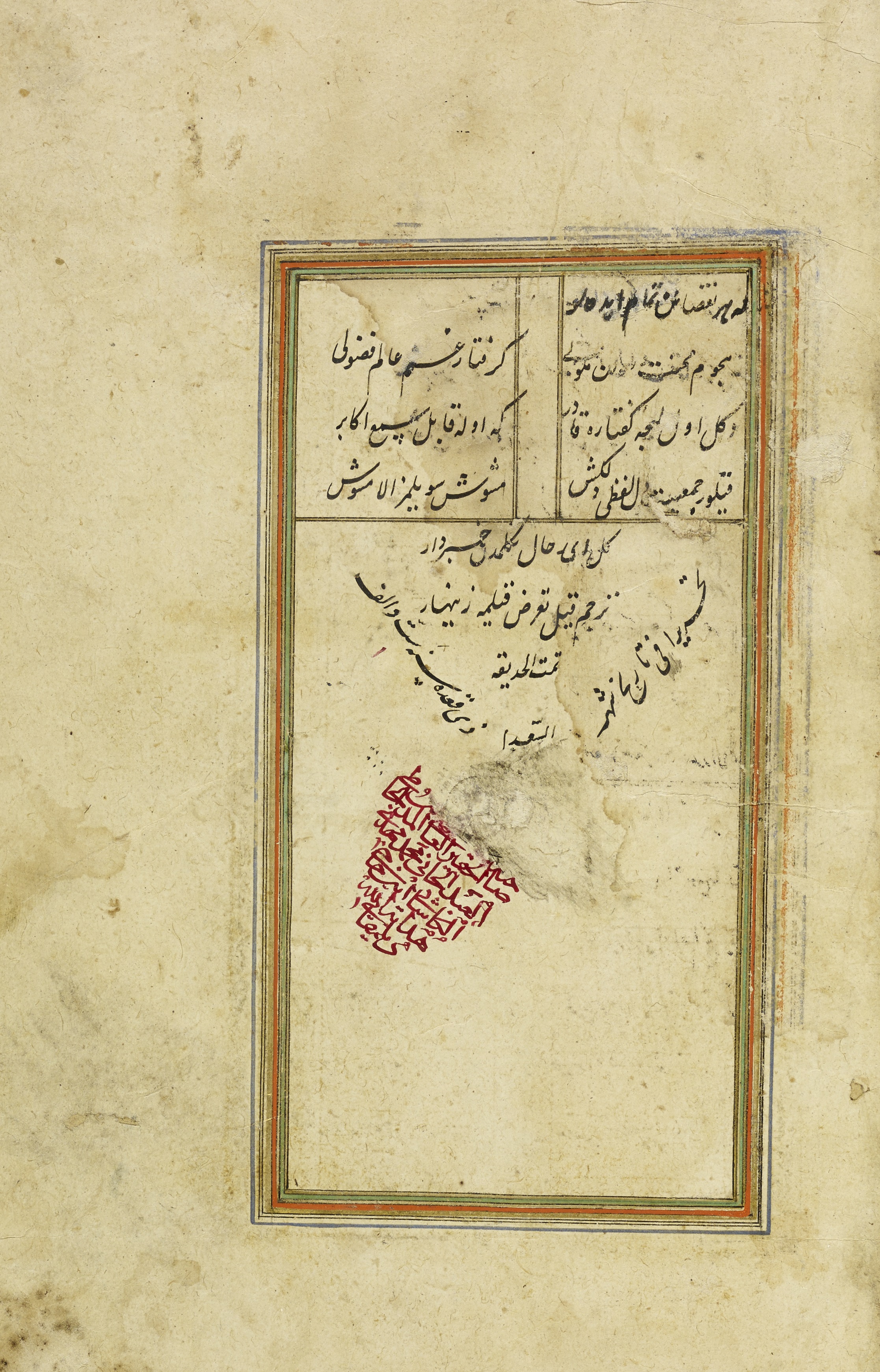

A colophon at the close of the manuscript indicates that the transcription of the text was completed in Dhū’l-Qaʿdah 1006 [June-July 1598] (see Gallery Image B). As reflected in the color palette, composition, and amalgamation of Persian and Turkish styles in its painted illustrations, the manuscript may represent yet another of the many illustrated copies of Hadikatü’s-süada produced in Baghdad during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century.2

A few former owners’ marks and inventory marks shed further light on the manuscript’s history. Two rubricated statements appearing at the opening and close of the text indicate that at some stage the manuscript was legally acquired by one Muḥammad Mahdī al-Kāshānī b. Ḥājjī Hidāyat Allāh Daylamqānī. An additional ownership statement on the opening folio was partially lost during the trimming of the text block and provides a terminus post quem of 1088 [1677-1678] for this intervention, presumably contemporary with the rebinding. Further, the manuscript bears the inventory mark of Tammaro De Marinis (1878-1969), a Florentine bookseller who supposedly acquired this and several other manuscripts in Istanbul before offering them in a sale that eventually reached the University of Michigan Library in 1924.3

About the author

Evyn Kropf is a librarian and curator at the University of Michigan Library where she teaches and engages in research on Islamic codicology and manuscript culture alongside her work developing and curating the Library’s collections. She obtained her Bachelor’s degree in Materials Science and Engineering from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville and her Master’s degree in Information Science with a specialization in Library and Information Services from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor where she also completed coursework in Arabic historiography and directed readings in classical Arabic and Ottoman Turkish. From 2009 to 2012 she led the “Collaboration in Cataloging: Islamic Manuscripts at Michigan” project, the descriptive effort that realized the detailed cataloguing of 904 codex manuscripts from the Library’s Islamic Manuscripts Collection.

Notes

1 See the article of Gottfried Hagen in this issue of Mizan, “Salvation and Suffering in Ottoman Stories of the Prophets.” On the maqtal genre, see Mahmoud M. Ayoub, Redemptive Suffering in Islam: A Study of the Devotional Aspects of Ashura in Twelver Shi’ism (Hamburg: De Gruyter, 1978).

2 See Rachel Milstein, Miniature Painting in Ottoman Baghdad (Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 1990).

3 For more on this acquisition, see Evyn Kropf, “Following the peregrinations of Isl. Ms. 350: Part 2, From Istanbul to Ann Arbor.”

On Michigan Manuscript Isl. Ms. 386

Fuẓūlī’s Garden of the Felicitous

About Michigan Isl. Ms. 386

This issue of Mizan dedicated to the Islamic tales of the prophets features a number of images from a manuscript preserved in the University of Michigan Library under the shelfmark Isl. Ms. 386.

The compact volume of beige Persianate paper carries a late sixteenth-century manuscript witness of Hadikatü’s-süada (Garden of the Felicitous), a maqtal or martyrology commemorating the suffering of the prophets, particularly the tragedy at Karbalāʾ, by the illustrious Turkish poet Fuẓūlī (d. 963/1556).1

The richly ornamented volume has been trimmed and resewn, and is presently bound in a two-piece cover of painted lacquerwork featuring a typical book cover composition of central mandorla and pendants in gold vegetal motifs. This cherished cover is likely not original to the present text block, but rather was produced for another manuscript, specially preserved and reused on this manuscript.

An illuminated headpiece sets off the opening of the text, and features a scalloped golden dome filled with floral-vegetal designs surmounting a cartouche carrying the title and author of the work in white riqāʿ script (see Gallery Image A).

The text is set in a spacious column of fifteen lines per page—occasionally divided into two columns to set off lines of verse—and written in a refined Ottoman talik (i.e. nastaʿlīq) that is characteristically serifless with a gentle effect of words descending to the baseline, elongated horizontal strokes, and pointing in distinct dots. Headings and keywords are rubricated or chrysographed and a polychrome frame surrounds the written area.

As with numerous other copies of the work, the manuscript is generously illustrated with thirteen paintings depicting episodes from the text, featuring the prophets and Alid imāms who are the work’s protagonists:

Abraham catapulted into the fire (p.17)

Abraham about to sacrifice his son (p.25)

Joseph’s brothers and the wolf before Jacob (p.48)

Pursuers sawing the tree in which Zechariah is hiding (p.75)

Ḥamzah beats Abū Jahl with his bow (p.92)

The Prophet Muḥammad in battle, likely at Uḥud (p.95)

The Prophet Muḥammad emerging from the cave (p.100)

ʿAlī in battle (p.103)

Death of the Prophet Muḥammad (p.137)

Assassination of ʿAlī (p.244)

Muslim b. ʿAqīl comes out against his attackers at Ṭawʿah’s house (p.357)

Duel of Qāsim b. Ḥasan and Azraq at Karbalāʾ (p.481)

Zayn al-ʿĀbidīn preaching in the mosque in exculpation of al-Ḥusayn (p.571)

As is typical, each prophet or imām is visually signified by a luminous halo, the flames of which often pierce the boundary of the written area and spill into the margins along with other elements of the composition. A later viewer with more reserved sensibilities toward the depiction of holy persons has added somewhat crude veils over the faces of the prophets.

A colophon at the close of the manuscript indicates that the transcription of the text was completed in Dhū’l-Qaʿdah 1006 [June-July 1598] (see Gallery Image B). As reflected in the color palette, composition, and amalgamation of Persian and Turkish styles in its painted illustrations, the manuscript may represent yet another of the many illustrated copies of Hadikatü’s-süada produced in Baghdad during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century.2

A few former owners’ marks and inventory marks shed further light on the manuscript’s history. Two rubricated statements appearing at the opening and close of the text indicate that at some stage the manuscript was legally acquired by one Muḥammad Mahdī al-Kāshānī b. Ḥājjī Hidāyat Allāh Daylamqānī. An additional ownership statement on the opening folio was partially lost during the trimming of the text block and provides a terminus post quem of 1088 [1677-1678] for this intervention, presumably contemporary with the rebinding. Further, the manuscript bears the inventory mark of Tammaro De Marinis (1878-1969), a Florentine bookseller who supposedly acquired this and several other manuscripts in Istanbul before offering them in a sale that eventually reached the University of Michigan Library in 1924.3

About the author

Evyn Kropf is a librarian and curator at the University of Michigan Library where she teaches and engages in research on Islamic codicology and manuscript culture alongside her work developing and curating the Library’s collections. She obtained her Bachelor’s degree in Materials Science and Engineering from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville and her Master’s degree in Information Science with a specialization in Library and Information Services from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor where she also completed coursework in Arabic historiography and directed readings in classical Arabic and Ottoman Turkish. From 2009 to 2012 she led the “Collaboration in Cataloging: Islamic Manuscripts at Michigan” project, the descriptive effort that realized the detailed cataloguing of 904 codex manuscripts from the Library’s Islamic Manuscripts Collection.

Notes

1 See the article of Gottfried Hagen in this issue of Mizan, “Salvation and Suffering in Ottoman Stories of the Prophets.” On the maqtal genre, see Mahmoud M. Ayoub, Redemptive Suffering in Islam: A Study of the Devotional Aspects of Ashura in Twelver Shi’ism (Hamburg: De Gruyter, 1978).

2 See Rachel Milstein, Miniature Painting in Ottoman Baghdad (Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 1990).

3 For more on this acquisition, see Evyn Kropf, “Following the peregrinations of Isl. Ms. 350: Part 2, From Istanbul to Ann Arbor.”